Published online Jan 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.7

Peer-review started: November 13, 2022

First decision: November 23, 2022

Revised: December 8, 2022

Accepted: December 23, 2022

Article in press: December 23, 2022

Published online: January 6, 2023

Processing time: 52 Days and 14.1 Hours

Diarrhea is a frequent symptom in postoperative patients with Crohn’s diseases (CD), and several different mechanisms likely account for postoperative diarrhea in CD. A targeted strategy based on a comprehensive understanding of postoperative diarrhea is helpful for better postoperative recovery.

Core Tip: Postoperative diarrhea can be divided into inflammatory and noninflammatory diarrhea. Because of the characteristics of Crohn's disease (CD), postoperative diarrhea is clinically very common; however, not much attention is paid to it. In this article, we review the causes, diagnoses, and treatments of postoperative diarrhea in CD.

- Citation: Wu EH, Guo Z, Zhu WM. Postoperative diarrhea in Crohn’s disease: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(1): 7-16

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i1/7.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i1.7

Crohn's disease (CD) is an unexplained intestinal inflammatory disease that affects the entire digestive tract. It involves chronic inflammation of the intestine, damage and distortion of tissue architecture, and loss of digestive functions. This can lead to intestinal stenosis; intestinal fistula; abdominal abscess; and other complications such as malnutrition, perianal lesions, and diarrhea. Statistically, > 50% of the patients with CD require surgical intervention for unmanageable disease, and many require repeated surgery for recurrent disease. Although biological agents reduce the risks associated with CD surgery, surgery is still one of the main treatments for CD. Diarrhea is a prevalent symptom of CD. Approximately 82% of the patients with CD present with diarrhea during the course of the disease[1]. Diarrhea is one of the important factors that affect the postoperative quality of life in patients with CD. Previous studies reported that the incidence of postoperative diarrhea was 24% in patients with colon cancer and 79% in patients with ileum resection of over 10 cm[2-4]. Postoperative diarrhea can be divided into inflammatory and noninflammatory diarrhea. Because of the characteristics of CD, postoperative diarrhea is clinically very common; however, not much attention is paid to it. In this article, we review the causes, diagnoses, and treatments of postoperative diarrhea in CD.

The gut microbiota is considered an additional organ of the human body and is populated by a complex and dynamic microbial ensemble[5]. According to previous studies, the number of bacterial species in gut microbiota range from 1000–1150 and each human has at least 160 species[5]. It is different in various parts of the intestine[6]. The homeostasis of gut microbiota is the basis of digestive functions. The gut microbiota of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by low microbial diversity, for instance, a reduction in Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus sp. and an increase in adherent/invasive Escherichia coli or Clostridium difficile compared with healthy controls[7-10]. As the diversity of gut microbiota is changed, its ability to respond to external environment changes[11,12].

The ileocecal valve can be considered a “fence” that isolates the contents of the colon and small intestine. The ileocecum is also the most commonly involved location in CD. Dysfunction of ileocecum may lead to the loss of this “fence” and alters the number and variety of microbiota species in the small intestine. Disturbance in the small intestinal microbiota would cause small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)[13]. A retrospective observational cohort research reported a substantial increase in the prevalence of SIBO in patients with CD compared with healthy individuals, and was independently linked to clinical relapse in quiescent patients[14]. CD patients were supposed to be at higher risk of SIBO after loss of ileocecum caused by resection. Overall, surgery will alter the intestinal histology, physiology, or microbiota and further aggravate dysbiosis. This would lead to the occurrence of SIBO and increased possibility of postoperative diarrhea[14,15].

In addition, some specific bacteria in the gut can cause diarrhea[16,17], such as adherent/invasive E. coli, C. difficile. An increase in the incidence and severity of C. difficile–associated diarrhea (CDAD) is observed in patients with CD[18-20]. Abdominal surgery is thought to be a risk factor for CDAD. The reported rates of postoperative CDAD range from 0.2%–8.4%[21-23]. Moreover, the use of antibiotics, glucocorticoid, and biological agents, would increase the risk of postoperative CDAD[10,24-28]. Therefore, we should pay attention to the specific bacteria related to postoperative diarrhea.

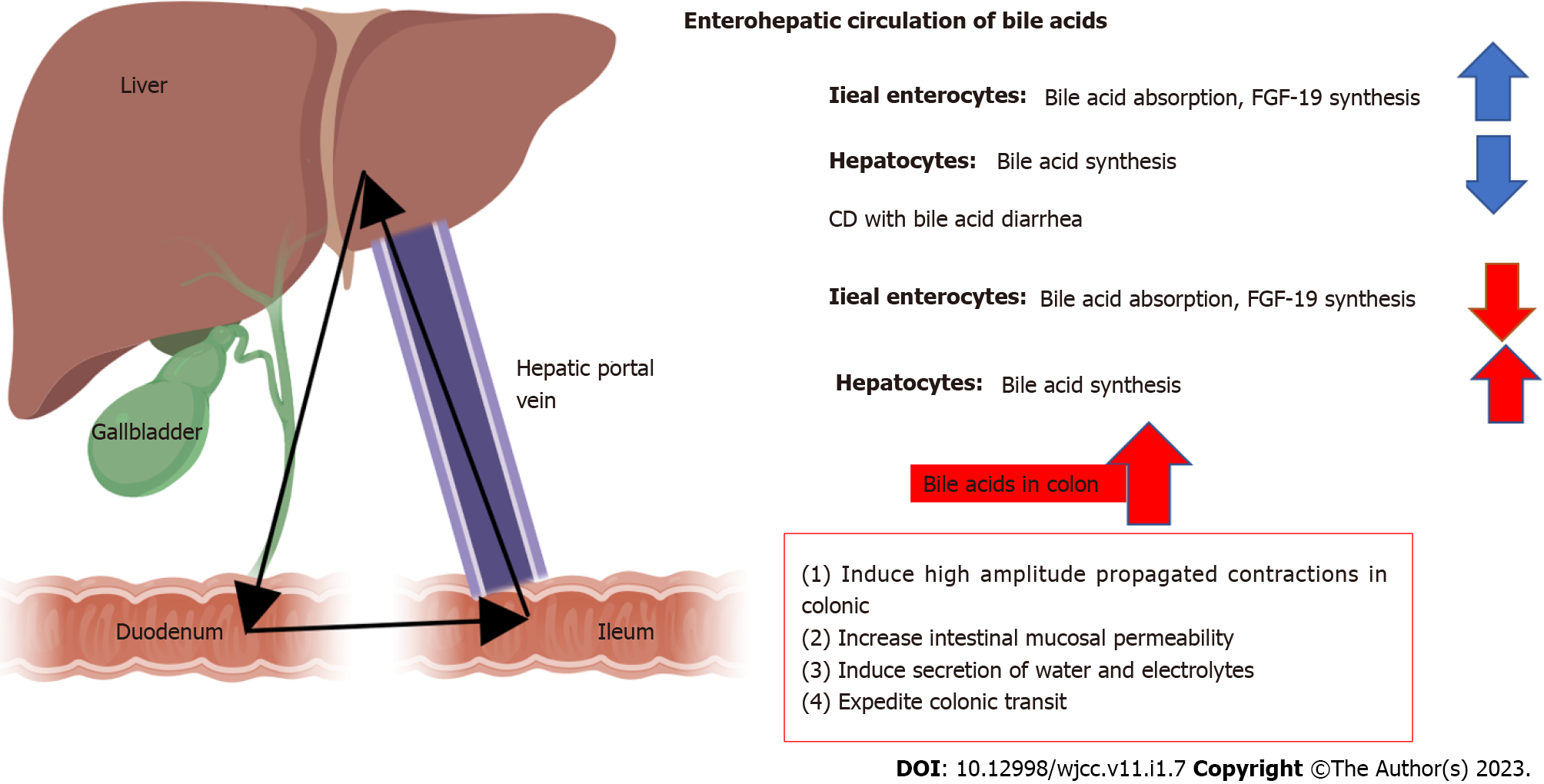

Bile Acid (BA) is the end-product of cholesterol catabolism and is synthesized in the liver, excreted into the duodenum in bile, reabsorbed in the ileum, and then recirculated back to the liver[29-32].

The effects of BA on the intestine include: (1) Inducing high amplitude propagated contractions in colonic; (2) increasing intestinal mucosal permeability; (3) inducing secretion of water and electrolytes; and (4) expediting colonic transit. Therefore, ileal dysfunction, impaired reabsorption, or disorders of BA metabolism would lead to diarrhea (Figure 1).

The types of BA diarrhea (BAD) are based on the original classification of BA malabsorption[33]: (1) Type 1: BAD caused by ileal dysfunction and impaired reabsorption, as related to CD in the ileum and/or ileal resection[34,35]; (2) Type 2: Primary or idiopathic BAD producing high levels of fecal BA, watery diarrhea, and response to BA sequestrants in the absence of ileal or other obvious gastrointestinal diseases. This type may be related to fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-19[36]; and (3) Type 3: BAD due to other gastrointestinal disorders that affect absorption, such as SIBO, celiac disease, or chronic pancreatitis[37].

Recent studies suggested that BA levels are significantly reduced in patients with IBD. Significant reductions of the pool size of chenodeoxycholic acid, and the total bile acid in patients with CD compared with those in normal subjects were observed[38]. Patients with active disease are more likely to have BA absorption disorders than those with inactive disease[39]. These may be partly due to a lack of intestinal mucosal BA transporter and low expression of FGF-19 in CD patients[31,40-42]. Besides, as BA was reabsorbed mainly in the ileum[31], patients with CD are more likely to develop type I BA diarrhea since most of them have ileal dysfunction and would undergo ileum resection. A study found that CD patients with < 1 m intestinal resections responded well to bile acid sequestrants, while those with > 1 m resections did not[43].

There are three types of watery diarrhea, namely, secretory, osmotic, and functional. Watery diarrhea is mainly caused by impaired permeability, functional disorders, and abnormal secretion. Certain food items with high permeability in the intestine make water enter into the small intestine through the intestinal epithelium from the plasma[44]. Watery diarrhea is common and any condition that causes an increase in osmotic pressure in the intestine, such as the use of lactulose, polyethylene glycol, and other laxatives, can lead to diarrhea. The role of enteral nutrition in the perioperative period of CD is receiving increasing attention. Studies have reported that preoperative enteral nutrition may reduce 30-d postoperative complications in patients with CD[45].

Patients who received preoperative nutritional optimization can be relieved from intestinal inflammation[46] and exhibit reduced incidence of anastomotic leakage[47]. The impact of postoperative enteral nutrition on patients with CD is important, although it is not conclusive whether postoperative enteral nutrition is used as a treatment to maintain remission after CD surgery[48]. However, a prospective clinical study suggested that postoperative enteral nutrition support after surgery may help in reducing the recurrence of CD[49]. Diarrhea caused by enteral nutrition can be attributed to the following reasons: (1) Osmotic pressure intolerance of enteral nutrition. Intestinal water absorption depends on the concentration difference between the intestinal cavity and intravascular colloid osmotic pressure. If the osmotic pressure of the enteral nutrition is too high, it can lead to significantly reduced intestinal water absorption, causing diarrhea. Patients with CD usually have intestinal edema due to malnutrition or hypoproteinemia, resulting in osmotic diarrhea due to poor intestinal absorption. About 65%-75% of patients with CD have undernutrition[50]; (2) Intolerance to enteral nutrition components. Lipase deficiency can occur postoperatively in patients. About 1.6% of patients with CD were diagnosed with celiac disease[51]. Infections or malnutrition can cause lactase deficiency. If the components of enteral nutrition contain substances that cannot be digested and absorbed, such as those with higher lipid content, it will lead to diarrhea; (3) If the enteral nutrition infusion speed is too fast, it will lead to diarrhea. Enteral nutrition contains a large number of nutrients. It is a good “bacterial culture medium.” The bacterial infection leads to disorders of intestinal flora, causing diarrhea. In recent years, strategy to enhance recovery after surgery is getting increasing attention. Early enteral nutrition support speeds up the postoperative recovery of patients. However, ignoring the influence of the above related factors may lead to postoperative diarrhea and affect postoperative recovery.

Diversion colitis is considered a nonspecific inflammation in the diverted colon. Glotzer named this inflammation “diversion colitis” in 1981. Since then, the disease has been reported in both retrospective and prospective studies[52-54]. The term diversion colitis (DC) is usually used in cases of resection of descending and/or sigmoid colon, in which the remaining rectum is either buried in the abdomen or externalized as a mucinous fistula. As a consequence of the absence of feces, SCFAs (which are the source of the left colon mucosa cells) are absent in the rectal or rectosigmoid energy stump, resulting in the appearance of an inflammatory process which may not substantially differ from the inflammation appearing in ulcerative colitis[55-57]. In CD, due to preoperative intestinal obstruction, intestinal fistula, or abdominal infection, the one-stage anastomosis may not be performed; diversion colitis may occur in these patients. The reason for diversion colitis may be a shortage of short-chain fatty acids[58]. Butyrate is a type of short-chain fatty acid and has been proven to reduce inflammation[59,60]. Studies have reported that patients with IBD have relatively low levels of short-chain fatty acids in the gut compared with healthy individuals[61]. Short-chain fatty acids are the main end-product of carbohydrate metabolism by bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract and constitute approximately 10% of the daily calories required by the human body[62]. Reduced levels of short-chain fatty acids can lead to reduced absorption of NaCl and water, resulting in diarrhea[63]. Patients with CD in the perioperative period may use antibiotics to control the infection, which will undoubtedly reduce the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids. Therefore, postoperatively, patients with CD may exhibit a higher probability of occurrence of diarrhea due to a lack of short-chain fatty acids than patients with other diseases.

Although surgery is able to alleviate the symptoms and resolve the related complications it can not cure CD. Most patients suffer postoperative recurrence. Studies have reported that the risk of post-operative endoscopic recurrence in CD was 90% by one year[64], and within 1 year after the surgery, nearly 30% of the CD patients developed clinical recurrence, and 5%–10% of them required surgical treatment[64,65]. The shortest recorded relapse time is within 1 wk after the surgery[66]. Histological disease activity in an endoscopically normal neoterminal ileum may occur as early as one week after surgery[67]. The most common clinical symptom of early intestinal inflammatory activity is diarrhea. Therefore, diarrhea is more likely to occur after surgery in patients with CD than in patients with other diseases.

Some patients with CD may have an increased area of intestinal legions as they may have had more intestinal mass removed by emergency surgery due to perforation. It is generally believed that to meet the body's nutritional needs, the small intestine should be at least 100-cm long and have a complete colon, and the small intestine that remains after colectomy should be more. The intestine has a strong compensatory capacity. The removal of 50% of the intestinal absorption area may not severely affect digestion and absorption; however, if > 75% of the intestinal absorption area is removed, the patients may exhibit short bowel syndrome after surgical treatment. The removal of a big mass of the small intestine leads to increased secretion of gastric acid, increased secretion by the small intestine and colon, and peristaltic acceleration, resulting in postoperative diarrhea. Patients with CD are at high risk for recurrent disease and often undergo multiple operations. A recent review suggests the incidence of SBS is 0.8% at 5 years, 3.6% at 10 years, and 8.5% at 20 years after surgery in CD[68]. IBD-related SBS remains a challenging issue.

Infection at the incision site may cause pain and the slow recovery of intestinal functions. Additionally, it may cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, and postoperative emotional anxiety. This type of diarrhea may be due to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). This clinical manifestation of diarrhea and abdominal pain is difficult to distinguish from IBD[69]. Marie systematically reviewed 12 studies and reported that postoperatively, patients with IBD had a higher risk of depression than other patients[70]. Symptoms of anxiety and depression are more common in Asian patients with IBD[71]. Due to the disease itself and the postoperative recurrence of CD, patients with CD may have a higher probability of acquiring IBS after surgery. IBS can affect gastrointestinal motility and change the gut microbiota, leading to diarrhea[72]. Patients with CD and IBS may have a higher risk of postoperative diarrhea than other patients.

Diarrhea should be assessed based on history and clinical features. Additionally, some specific clinical features can help us to investigate the cause of diarrhea[73]. For instance, in diarrhea caused by bacteria, feces can have specific odors, e.g., fishy. Considering the possibility of bacterial infection, diarrhea caused by C. difficile often exhibits "egg patterns," and with a severe C. difficile infection, exfoliated intestinal mucosa can be observed in feces. In diarrhea caused by BAD, the color of feces is often "dark green." In osmotic diarrhea, undigested enteral nutrition may be observed in the feces. Intestinal mucus is often observed in the feces of patients with diversion colitis. In diarrhea due to short bowel syndrome, feces are bulky and contain undigested food. Patients with IBS after surgery for CD may simply present with an increased frequency of defecation; however, the volume of feces is not large. Medical history should include the patient's past physical condition, recent drug history, eating habits, and other related problems. Characteristics of the feces, including the presence of visible blood, pus, mucus, fat, and undigested food particles, may suggest a potential pathophysiological mechanism and guide further evaluation. Moreover, it is important to review the diet and medication history. Abdominal examination should be done in order to confirm or exclude acute abdominal processes. Rectal examination is mandatory to assess the presence of blood in stool and stool consistency.

Laboratory tests should include routine blood, electrolytes, liver function, and renal function tests. If a patient has malabsorption, the status of trace elements should be clarified. The relevant examination results can indicate whether a patient has metabolic disorders and help the doctor in assessing the patient's current physical condition. Analysis of feces can provide important information, particularly for patients with CD. Fecal calprotectin is a very sensitive marker for inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract and is useful for differentiating IBD from IBS. Fecal calprotectin is used in the diagnosis of IBD, monitoring disease activity, treatment guidance, and prediction of disease relapse and postoperative recurrence[74-76]. Besides, endoscopy or radiologic imaging should be consider if the diagnosis is unclear.

Diarrhea is usually caused by a single factor; however, for patients with CD, diarrhea should be assessed in detail. First, CD is a type of intestinal inflammation with unknown causes, and intestinal inflammation can cause diarrhea. Second, intestinal function is correlated with the intestinal environment and gut microbiota. These factors may interact with each other. Surgical treatment is a strategy to relieve the symptoms of the disease but not to cure the disease. Moreover, postoperative lesions can cause diarrhea. After surgical treatment, the cause of preoperative diarrhea may change, and the strategy to treat postoperative diarrhea should be changed according to the course of the disease. Therefore, postoperative diarrhea in patients with CD needs to be evaluated from multiple perspectives.

Diarrhea can be acute, persistent, or chronic. The majority of cases of acute diarrhea are self-limiting. Patients with signs of dehydration, such as dry mouth, swollen tongue, and change in mental status, should be noticed. Therapeutic options in acute diarrhea patients include oral rehydration, early refeeding, antidiarrheal medications, antibiotics, probiotics. However, for patients with CD, the treatment strategy for diarrhea needs to be designed after considering patients' medical history, medication, surgical methods to make a comprehensive judgment. Some patients may require comprehensive treatment because of two or more factors. The treatment method is flexible for patients with diarrhea due to the same cause.

Diarrhea due to inflammatory disease, controlling inflammation is extremely important. Medications, such as cortisol hormones, immunosuppressants, and biological agents, are used to induce and maintain clinical remission. The choice of drugs should be based on the patient's previous treatment[77-79]. In cases of enteric infection, appropriate antimicrobial therapy should be provided. CDAD is initially treated with metronidazole. Early use of vancomycin is recommended for patients with symptoms of severe CDAD or if a patient’s condition fails to improve or deteriorates after metronidazole administration. If there is evidence of SIBO, antibiotics such as tetracyclines, ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, or rifaximin can be considered. In patients with ileal disease or resection, cholestyramine can ameliorate or abolish diarrhea by binding to bile salts in the lumen of the intestine. Cholestyramine is given in divided doses before meals and separated from other medications. Many patients with diarrhea-predominant IBD benefit from nonspecific antidiarrheal therapy. Opiate drugs, such as loperamide and diphenoxylate, primarily slow intestinal transit and allow more contact time for absorption. Probiotics may be also useful. Recently, A meta-analysis showed a moderate protective effect of probiotics for preventing antibiotic-associated diarrhea[80].

For patients with enterostomy, distal intestinal perfusion with liquid containing short-chain fatty acids can be used to prevent postoperative diarrhea[81,82]. In addition, chyme reinfusion is a method to prevent postoperative diarrhea[83]. Some studies have reported that patients with CD can benefit from the use of enteral nutrition preparations[84]. The selection of appropriate enteral nutrition preparation, combined with parenteral nutrition, can ensure a balance of homeostasis. Diarrhea can be controlled by adjusting the amount and drip rate of enteral nutrition and the appropriate use of antidiarrheal agents and dietary fiber. The treatment strategy can be gradually changed according to the patient's condition[85]. Clinically, the maintenance and treatment of patient’s mental health is an important part of their postoperative clinical recovery[71]. It should be noted that the causes of postoperative diarrhea in patients with CD may change with the treatment and postoperative recovery. Due to the characteristics of CD, we should pay attention to whether the adverse reactions of the drugs will have adverse effects on the disease during the treatment (Table 1).

| Cause | Treatment |

| Gut microbiota disorders | Antimicrobial therapy; Probiotics |

| Bile acid diarrhea | Cholestyramine |

| Watery diarrhea | Antidiarrheal agents |

| Diversion colitis or short-chain fatty acid deficiency | short-chain fatty acid used before surgical |

| Early postoperative inflammatory activity | Anti-inflammatory medication |

| Short bowel syndrome | Parenteral nutrition; Opiate drugs |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Fiber supplements; Antispasmodics, antidiarrheal agents |

Postoperative diarrhea is very common in CD. Severe diarrhea can lead to disturbed homeostasis of the internal environment, insufficient fluid in body, and aggravation of systemic reactions that seriously affect postoperative recovery. Diarrhea is caused by various factors, which may be related and interact with each other. For patients undergoing surgical treatment for CD, the most obvious change is the change in intestinal histology, physiology, or microbiota, and this change may lead to a difference between preoperative and postoperative diarrhea. A targeted strategy based on a comprehensive understanding of postoperative diarrhea is helpful for better postoperative recovery.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Marteau P, France; Nakamura M, Japan; Triantafillidis J, Greece S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH; IBSEN Group. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 834] [Cited by in RCA: 873] [Article Influence: 48.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bruckstein AH. Acute diarrhea. Am Fam Physician. 1988;38:217-228. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Brunet E, Caixàs A, Puig V. Review of the management of diarrhea syndrome after a bariatric surgery. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr (Engl Ed). 2020;67:401-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gendre JP. [Diarrhea after digestive surgery]. Rev Prat. 1989;39:2607-2609. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, Mende DR, Li J, Xu J, Li S, Li D, Cao J, Wang B, Liang H, Zheng H, Xie Y, Tap J, Lepage P, Bertalan M, Batto JM, Hansen T, Le Paslier D, Linneberg A, Nielsen HB, Pelletier E, Renault P, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Turner K, Zhu H, Yu C, Jian M, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zhang X, Qin N, Yang H, Wang J, Brunak S, Doré J, Guarner F, Kristiansen K, Pedersen O, Parkhill J, Weissenbach J; MetaHIT Consortium, Bork P, Ehrlich SD, Wang J. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9101] [Cited by in RCA: 7840] [Article Influence: 522.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 6. | Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Relman DA. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635-1638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5700] [Cited by in RCA: 5592] [Article Influence: 279.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Ott SJ, Musfeldt M, Wenderoth DF, Hampe J, Brant O, Fölsch UR, Timmis KN, Schreiber S. Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:685-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 875] [Cited by in RCA: 937] [Article Influence: 44.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Andoh A, Kuzuoka H, Tsujikawa T, Nakamura S, Hirai F, Suzuki Y, Matsui T, Fujiyama Y, Matsumoto T. Multicenter analysis of fecal microbiota profiles in Japanese patients with Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1298-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Darfeuille-Michaud A, Boudeau J, Bulois P, Neut C, Glasser AL, Barnich N, Bringer MA, Swidsinski A, Beaugerie L, Colombel JF. High prevalence of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli associated with ileal mucosa in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:412-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1075] [Cited by in RCA: 1123] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rodemann JF, Dubberke ER, Reske KA, Seo DH, Stone CD. Incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:339-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, Jansson JK, Knight R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3051] [Cited by in RCA: 3648] [Article Influence: 280.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:577-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1339] [Cited by in RCA: 1376] [Article Influence: 80.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Pimentel M, Saad RJ, Long MD, Rao SSC. ACG Clinical Guideline: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:165-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wei J, Feng J, Chen L, Yang Z, Tao H, Li L, Xuan J, Wang F. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated with clinical relapse in patients with quiescent Crohn's disease: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shah A, Morrison M, Burger D, Martin N, Rich J, Jones M, Koloski N, Walker MM, Talley NJ, Holtmann GJ. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:624-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Buisson A, Sokol H, Hammoudi N, Nancey S, Treton X, Nachury M, Fumery M, Hébuterne X, Rodrigues M, Hugot JP, Boschetti G, Stefanescu C, Wils P, Seksik P, Le Bourhis L, Bezault M, Sauvanet P, Pereira B, Allez M, Barnich N; Remind study group. Role of adherent and invasive Escherichia coli in Crohn's disease: lessons from the postoperative recurrence model. Gut. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Machiels K, Pozuelo Del Río M, Martinez-De la Torre A, Xie Z, Pascal Andreu V, Sabino J, Santiago A, Campos D, Wolthuis A, D'Hoore A, De Hertogh G, Ferrante M, Manichanh C, Vermeire S. Early Postoperative Endoscopic Recurrence in Crohn's Disease Is Characterised by Distinct Microbiota Recolonisation. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1535-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Archibald LK, Banerjee SN, Jarvis WR. Secular trends in hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile disease in the United States, 1987-2001. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1585-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hermsen JL, Dobrescu C, Kudsk KA. Clostridium difficile infection: a surgical disease in evolution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1512-1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Kollef MH. Increase in adult Clostridium difficile-related hospitalizations and case-fatality rate, United States, 2000-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:929-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wren SM, Ahmed N, Jamal A, Safadi BY. Preoperative oral antibiotics in colorectal surgery increase the rate of Clostridium difficile colitis. Arch Surg. 2005;140:752-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Crabtree T, Aitchison D, Meyers BF, Tymkew H, Smith JR, Guthrie TJ, Munfakh N, Moon MR, Pasque MK, Lawton J, Moazami N, Damiano RJ Jr. Clostridium difficile in cardiac surgery: risk factors and impact on postoperative outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1396-1402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kent KC, Rubin MS, Wroblewski L, Hanff PA, Silen W. The impact of Clostridium difficile on a surgical service: a prospective study of 374 patients. Ann Surg. 1998;227:296-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bossuyt P, Verhaegen J, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S. Increasing incidence of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:4-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jen MH, Saxena S, Bottle A, Aylin P, Pollok RC. Increased health burden associated with Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1322-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Saeian K, Binion DG. Temporal trends in disease outcomes related to Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:976-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Issa M, Vijayapal A, Graham MB, Beaulieu DB, Otterson MF, Lundeen S, Skaros S, Weber LR, Komorowski RA, Knox JF, Emmons J, Bajaj JS, Binion DG. Impact of Clostridium difficile on inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:345-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Singh H, Nugent Z, Yu BN, Lix LM, Targownik LE, Bernstein CN. Higher Incidence of Clostridium difficile Infection Among Individuals With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:430-438.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sayin SI, Wahlström A, Felin J, Jäntti S, Marschall HU, Bamberg K, Angelin B, Hyötyläinen T, Orešič M, Bäckhed F. Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. Cell Metab. 2013;17:225-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1367] [Cited by in RCA: 1683] [Article Influence: 140.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Fiorucci S, Carino A, Baldoni M, Santucci L, Costanzi E, Graziosi L, Distrutti E, Biagioli M. Bile Acid Signaling in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:674-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fitzpatrick LR, Jenabzadeh P. IBD and Bile Acid Absorption: Focus on Pre-clinical and Clinical Observations. Front Physiol. 2020;11:564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dawson PA, Karpen SJ. Intestinal transport and metabolism of bile acids. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:1085-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Camilleri M. Bile Acid diarrhea: prevalence, pathogenesis, and therapy. Gut Liver. 2015;9:332-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hofmann AF, Poley JR. Cholestyramine treatment of diarrhea associated with ileal resection. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:397-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hofmann AF, Poley JR. Role of bile acid malabsorption in pathogenesis of diarrhea and steatorrhea in patients with ileal resection. I. Response to cholestyramine or replacement of dietary long chain triglyceride by medium chain triglyceride. Gastroenterology. 1972;62:918-934. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Wedlake L, A'Hern R, Russell D, Thomas K, Walters JR, Andreyev HJ. Systematic review: the prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:707-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lundåsen T, Gälman C, Angelin B, Rudling M. Circulating intestinal fibroblast growth factor 19 has a pronounced diurnal variation and modulates hepatic bile acid synthesis in man. J Intern Med. 2006;260:530-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nishida T, Miwa H, Yamamoto M, Koga T, Yao T. Bile acid absorption kinetics in Crohn's disease on elemental diet after oral administration of a stable-isotope tracer with chenodeoxycholic-11, 12-d2 acid. Gut. 1982;23:751-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Gothe F, Beigel F, Rust C, Hajji M, Koletzko S, Freudenberg F. Bile acid malabsorption assessed by 7 alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: correlation to clinical and laboratory findings. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1072-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cao L, Che Y, Meng T, Deng S, Zhang J, Zhao M, Xu W, Wang D, Pu Z, Wang G, Hao H. Repression of intestinal transporters and FXR-FGF15 signaling explains bile acids dysregulation in experimental colitis-associated colon cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:63665-63679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Jahnel J, Fickert P, Hauer AC, Högenauer C, Avian A, Trauner M. Inflammatory bowel disease alters intestinal bile acid transporter expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 2014;42:1423-1431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Uchiyama K, Kishi H, Komatsu W, Nagao M, Ohhira S, Kobashi G. Lipid and Bile Acid Dysmetabolism in Crohn's Disease. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:7270486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Barkun AN, Love J, Gould M, Pluta H, Steinhart H. Bile acid malabsorption in chronic diarrhea: pathophysiology and treatment. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:653-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Camilleri M, Sellin JH, Barrett KE. Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Management of Chronic Watery Diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:515-532.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Meade S, Patel KV, Luber RP, O'Hanlon D, Caracostea A, Pavlidis P, Honap S, Anandarajah C, Griffin N, Zeki S, Ray S, Mawdsley J, Samaan MA, Anderson SH, Darakhshan A, Adams K, Williams A, Sanderson JD, Lomer M, Irving PM. A retrospective cohort study: pre-operative oral enteral nutritional optimisation for Crohn's disease in a UK tertiary IBD centre. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56:646-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wall CL, Day AS, Gearry RB. Use of exclusive enteral nutrition in adults with Crohn's disease: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7652-7660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Guo Z, Guo D, Gong J, Zhu W, Zuo L, Sun J, Li N, Li J. Preoperative Nutritional Therapy Reduces the Risk of Anastomotic Leakage in Patients with Crohn's Disease Requiring Resections. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:5017856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Narula N, Dhillon A, Zhang D, Sherlock ME, Tondeur M, Zachos M. Enteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD000542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Yamamoto T, Nakahigashi M, Umegae S, Kitagawa T, Matsumoto K. Impact of long-term enteral nutrition on clinical and endoscopic recurrence after resection for Crohn's disease: A prospective, non-randomized, parallel, controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kelly DG, Fleming CR. Nutritional considerations in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1995;24:597-611. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Mårild K, Söderling J, Lebwohl B, Green PHR, Pinto-Sanchez MI, Halfvarson J, Roelstraete B, Olén O, Ludvigsson JF. Association of Celiac Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:1471-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Glotzer DJ, Glick ME, Goldman H. Proctitis and colitis following diversion of the fecal stream. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:438-441. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Korelitz BI, Cheskin LJ, Sohn N, Sommers SC. The fate of the rectal segment after diversion of the fecal stream in Crohn's disease: its implications for surgical management. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Whelan RL, Abramson D, Kim DS, Hashmi HF. Diversion colitis. A prospective study. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Tominaga K, Kamimura K, Takahashi K, Yokoyama J, Yamagiwa S, Terai S. Diversion colitis and pouchitis: A mini-review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1734-1747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Gorgun E, Remzi FH. Complications of ileoanal pouches. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17:43-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 57. | Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Schroeder TK. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 947] [Cited by in RCA: 854] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Murray FE, O'Brien MJ, Birkett DH, Kennedy SM, LaMont JT. Diversion colitis. Pathologic findings in a resected sigmoid colon and rectum. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1404-1408. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 59. | Hudcovic T, Kolinska J, Klepetar J, Stepankova R, Rezanka T, Srutkova D, Schwarzer M, Erban V, Du Z, Wells JM, Hrncir T, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, Kozakova H. Protective effect of Clostridium tyrobutyricum in acute dextran sodium sulphate-induced colitis: differential regulation of tumour necrosis factor-α and interleukin-18 in BALB/c and severe combined immunodeficiency mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:356-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Magnusson MK, Isaksson S, Öhman L. The Anti-inflammatory Immune Regulation Induced by Butyrate Is Impaired in Inflamed Intestinal Mucosa from Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Inflammation. 2020;43:507-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Huda-Faujan N, Abdulamir AS, Fatimah AB, Anas OM, Shuhaimi M, Yazid AM, Loong YY. The impact of the level of the intestinal short chain Fatty acids in inflammatory bowel disease patients versus healthy subjects. Open Biochem J. 2010;4:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | van der Beek CM, Dejong CHC, Troost FJ, Masclee AAM, Lenaerts K. Role of short-chain fatty acids in colonic inflammation, carcinogenesis, and mucosal protection and healing. Nutr Rev. 2017;75:286-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Binder HJ. Role of colonic short-chain fatty acid transport in diarrhea. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:297-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 64. | Buisson A, Chevaux JB, Allen PB, Bommelaer G, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Review article: the natural history of postoperative Crohn's disease recurrence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:625-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lochs H, Löfberg R, Modigliani R, Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Schölmerich J, Stange EF, Sutherland LR. A review of activity indices and efficacy endpoints for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:512-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | De Cruz P, Kamm MA, Prideaux L, Allen PB, Desmond PV. Postoperative recurrent luminal Crohn's disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:758-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Olaison G, Smedh K, Sjödahl R. Natural course of Crohn's disease after ileocolic resection: endoscopically visualised ileal ulcers preceding symptoms. Gut. 1992;33:331-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 68. | Watanabe K, Sasaki I, Fukushima K, Futami K, Ikeuchi H, Sugita A, Nezu R, Mizushima T, Kameoka S, Kusunoki M, Yoshioka K, Funayama Y, Watanabe T, Fujii H, Watanabe M. Long-term incidence and characteristics of intestinal failure in Crohn's disease: a multicenter study. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:231-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Lacy BE, Pimentel M, Brenner DM, Chey WD, Keefer LA, Long MD, Moshiree B. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:17-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 117.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Zangenberg MS, El-Hussuna A. Psychiatric morbidity after surgery for inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:8651-8659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Chan W, Shim HH, Lim MS, Sawadjaan FLB, Isaac SP, Chuah SW, Leong R, Kong C. Symptoms of anxiety and depression are independently associated with inflammatory bowel disease-related disability. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:1314-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Altomare A, Di Rosa C, Imperia E, Emerenziani S, Cicala M, Guarino MPL. Diarrhea Predominant-Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-D): Effects of Different Nutritional Patterns on Intestinal Dysbiosis and Symptoms. Nutrients. 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V, Barbara G, Tomassetti P, De Giorgio R. Clinical approach to diarrhea. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7 Suppl 3:S255-S262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Ye L, Cheng W, Chen BQ, Lan X, Wang SD, Wu XC, Huang W, Wang FY. Levels of Faecal Calprotectin and Magnetic Resonance Enterocolonography Correlate with Severity of Small Bowel Crohn's Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Sarsu SB, Erbagci AB, Ulusal H, Karakus SC, Bulbul ÖG. The Place of Calprotectin, Lactoferrin, and High-Mobility Group Box 1 Protein on Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis with Children. Indian J Surg. 2017;79:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Henderson P, Anderson NH, Wilson DC. The diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin during the investigation of suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:637-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ; Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:465-83; quiz 464, 484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Travis SP, Stange EF, Lémann M, Oresland T, Bemelman WA, Chowers Y, Colombel JF, D'Haens G, Ghosh S, Marteau P, Kruis W, Mortensen NJ, Penninckx F, Gassull M; European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). European evidence-based Consensus on the management of ulcerative colitis: Current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:24-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Lémann M, Söderholm J, Colombel JF, Danese S, D'Hoore A, Gassull M, Gomollón F, Hommes DW, Michetti P, O'Morain C, Oresland T, Windsor A, Stange EF, Travis SP; European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: Current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 1032] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 80. | Guo Q, Goldenberg JZ, Humphrey C, El Dib R, Johnston BC. Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;4:CD004827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Luceri C, Femia AP, Fazi M, Di Martino C, Zolfanelli F, Dolara P, Tonelli F. Effect of butyrate enemas on gene expression profiles and endoscopic/histopathological scores of diverted colorectal mucosa: A randomized trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:27-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Komorowski RA. Histologic spectrum of diversion colitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:548-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Duan M, Cao L, Gao L, Gong J, Li Y, Zhu W. Chyme Reinfusion Is Associated with Lower Rate of Postoperative Ileus in Crohn's Disease Patients After Stoma Closure. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Zhu W, Guo Z, Zuo L, Gong J, Li Y, Gu L, Cao L, Li N, Li J. CONSORT: Different End-Points of Preoperative Nutrition and Outcome of Bowel Resection of Crohn Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Weiming Z, Ning L, Jieshou L. Effect of recombinant human growth hormone and enteral nutrition on short bowel syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |