Published online Mar 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2871

Peer-review started: September 18, 2021

First decision: January 10, 2022

Revised: January 19, 2022

Accepted: February 20, 2022

Article in press: February 20, 2022

Published online: March 26, 2022

Processing time: 185 Days and 9.4 Hours

Intramural pregnancy is a rare type of ectopic pregnancy, which is diagnosed by transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. Management strategies vary depending on the site of the pregnancy, the gestational age and the desire to maintain fertility. The incidence of intramural pregnancy in assisted reproductive technology is higher than that in natural pregnancy.

We present a case of intramural pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and elective single embryo transfer following salpingectomy. The patient was completely asymptomatic and her serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin level increased from 290 mIU/mL to 1759 mIU/mL. Three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound indicated a heterogeneous echogenic mass arising from the uterine fundus which was surrounded by myometrium and a slender and extremely hypoechoic area stretching to the uterine cavity which was thought to be a fistulous tract. Therefore, we considered a diagnosis of intramural pregnancy and laparoscopic surgery was conducted at 7 wk gestation.

Early diagnosis and treatment of intramural pregnancy is significant for maintaining fertility.

Core Tip: We present a case of intramural pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and elective single embryo transfer following bilateral salpingectomy. The patient was diagnosed with intramural pregnancy by transvaginal ultrasound and then underwent laparoscopic surgery at 7 wk’ gestation. The patient recovered well at discharge and her serum β-hCG levels were negative after 4 wk.

- Citation: Xie QJ, Li X, Ni DY, Ji H, Zhao C, Ling XF. Intramural pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(9): 2871-2877

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i9/2871.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i9.2871

Intramural pregnancy is a rare type of ectopic pregnancy, which is characterized by a gestational sac implanted within the myometrium and not connected to the uterine cavity[1]. Uterine rupture and massive bleeding are potential life-threatening complications of severe ectopic pregnancy. The risk factors for intramural pregnancy remain elusive, but may include uterine trauma, adenomyosis, inflammation of the uterine serosa and in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET)[1-3]. Transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful for diagnosis in early pregnancy. There is no consensus regarding the treatment of intramural pregnancy, including expectant management, surgical evacuation, uterine artery embolization (UAE) and methotrexate administration[4-7]. The incidence of ectopic pregnancy in assisted reproductive technology (ART) is about 2-5 times higher than that in natural pregnancy[8]. Timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment of intramural pregnancy is crucial in ART especially in patients who wish to preserve their fertility.

We report a case of intramural pregnancy following IVF and elective single ET, which was managed with laparoscopy.

A 31-year-old woman, gravidity three, parity zero, was admitted because of a suspected intramural pregnancy after IVF-ET.

The patient was completely asymptomatic. She had regular menstruation, a moderate amount of menstruation and no dysmenorrhea. Her last menstrual period was November 17, 2020. The endometrium was prepared using hormone replacement therapy following 1.875 mg of subcutaneous gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (Leuprorelin Acetate, Livzon Pharmaceuticals, China) on day 3 of the menstrual cycle. In addition, 90 mg of vaginal progesterone (Crinone, Merck Serono, United Kingdom) once a day and 10 mg of dydrogesterone three times daily were administered (P + 0). A frozen day 6 embryo which had undergone preimplantation genetic screening was transferred on the 7th day of progesterone exposure (P + 6) under sonographic guidance.

She received laparoscopic salpingotomy in 2014 due to a right tubal pregnancy. She had suffered secondary infertility since December 2015 and her hysterosalpingography results showed an obstruction in the right fallopian tube and adhesion of the distal end of the left fallopian tube in June 2016. As spontaneous pregnancy did not subsequently occur, she was referred to the reproductive center of our hospital for IVF-ET in June 2018. The patient underwent laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy for bilateral tubal pregnancy after two frozen day 3 embryos were transferred in December 2018. Of the other three frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles, a total of 5 embryos were transferred, but pregnancy was not achieved. In addition, the patient had a history of hysteroscopy three times to remove endometrial polyps and separate uterine adhesions.

Her personal history and family history were unremarkable.

The patient’s vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed a 7-week sized uterus with no tenderness and no abnormalities in the uterine cervix and abdomen. There was no vaginal bleeding or fluid.

At day 14 after ET, her serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) level was 111.54 mIU/mL and then increased from 290 mIU/mL to 1759 mIU/mL. On day 32 after ET, her serum β-hCG level was 3819 mIU/mL.

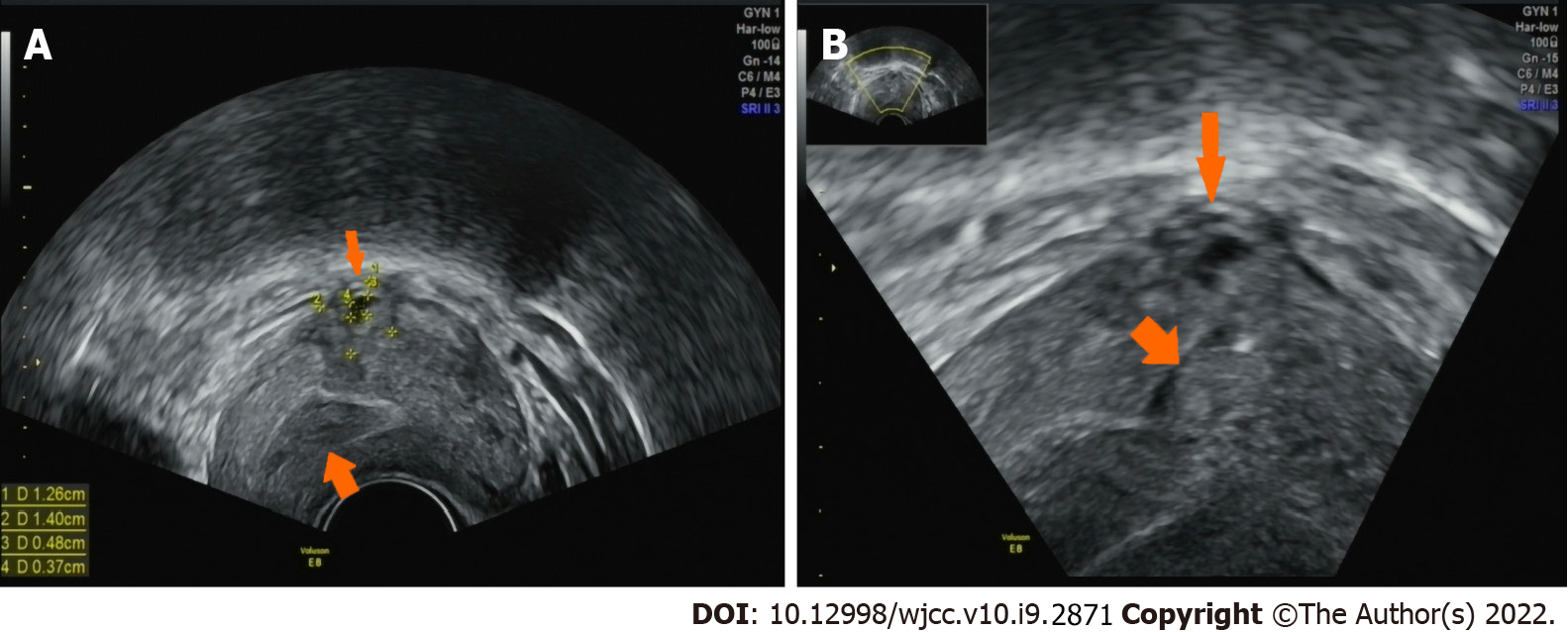

A transvaginal ultrasound examination revealed a suspected intramural pregnancy. When admitted on day 33 after ET, three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound indicated a heterogeneous echogenic area measuring 1.40 cm × 1.26 cm in size arising from the uterine fundus which had a 0.48 cm × 0.37 cm anechoic region inside and was surrounded by myometrium (Figure 1A). Color Doppler ultrasound showed abundant blood flow. This region seemed to have a slender and extremely hypoechoic area stretching to the uterine cavity (Figure 1B). In addition, a hypoechoic structure with an indistinct boundary measuring 2.74 cm × 1.61 cm in size was observed in the anterior myometrium near the uterine fundus, which was thought to be a uterine adenomyoma.

The final diagnosis in this case was intramural pregnancy after IVF-ET, and adenomyoma.

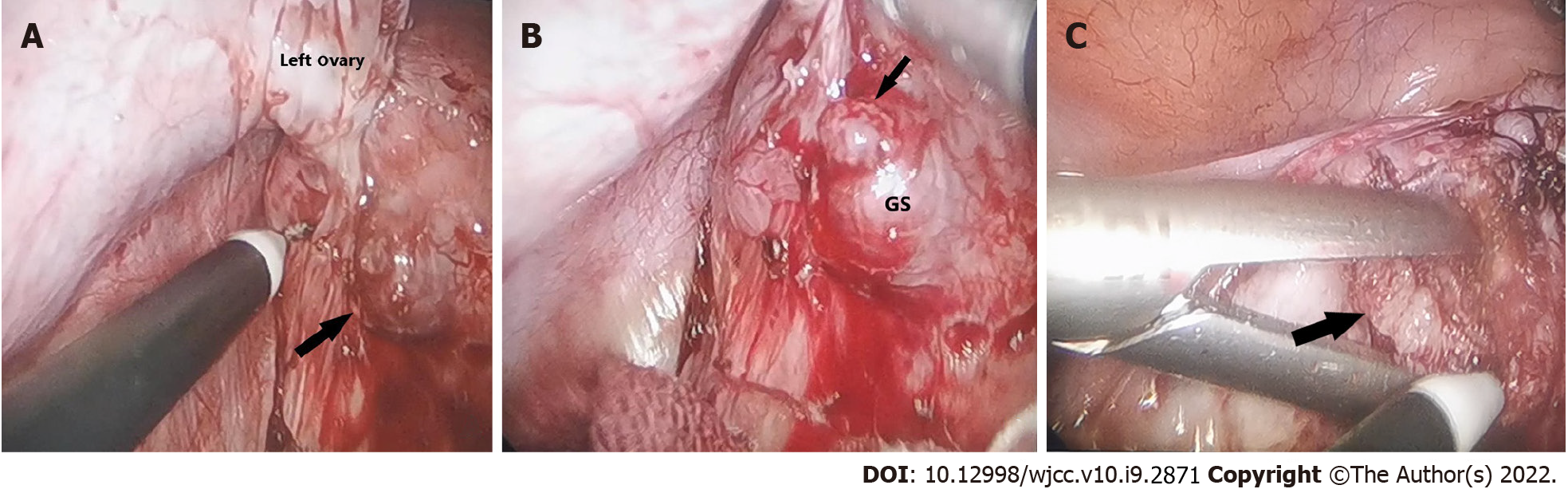

Considering the suspected diagnosis of intramural pregnancy with a possible fistulous tract communicated with the uterine cavity and the patient’s desire to maintain fertility, the decision was made to perform laparoscopic exploration. Laparoscopic surgery was performed on day 34 after ET. Laparoscopy showed a bulging and unruptured mass measuring approximately 2 cm in the left side of the anterior uterus with a purplish-blue-colored surface (Figure 2A). The fallopian tubes were absent on both sides and the ovaries appeared normal. The intramural ectopic pregnancy was dissected from the uterus which had chorionic villous tissues bulging out (Figure 2B). The wound was sutured continuously and methotrexate [Pfizer (Perth) Pty Limited, United States] was injected into the myometrium around the wound to eliminate the activity of possible residual trophoblast cells. The tumor-like bulging mass measuring 2 cm in the posterior wall of the uterus was resected and lysis of pelvic adhesions was carried out (Figure 2C).

Histological examination confirmed the presence of trophoblast cells and chorionic villi in the uterine smooth muscle. Her serum β-hCG levels declined to 837.37 mIU/mL 2 days after surgery. The patient was well at discharge and her serum β-hCG levels were negative after 4 wk.

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy after ART is 1.6%-8.6% higher than that in natural pregnancy. The incidence of intramural pregnancy is less than 1% of all ectopic pregnancies[9,10]. Intramural pregnancy is a rare type of ectopic pregnancy and refers to a gestational sac completely surrounded by the myometrium which is not connected to the endometrial cavity and the fallopian tubes. To date, very few cases of intramural pregnancy after IVF-ET have been reported in the literature[11-13].

Intramural pregnancy may present with a wide variety of symptoms and the clinical course is determined by its exact location, extent of myometrial involvement and gestational age. The exact cause of intramural pregnancy is unknown, but several hypotheses have been suggested including uterine surgical procedures (such as cesarean section, myomectomy, hysteroscopy, uterine curettage and a history of uterine perforation)[9,14,15], inflammation of the uterine serosa, IVF-ET[11-13] and adenomyosis[1,3]. Color Doppler ultrasound may show a suspected fistulous tract connecting the intramural pregnancy foci to the uterine cavity. In our case, the patient had a history of hysteroscopy three times and the presence of an adenomyoma in the posterior wall of the uterus confirmed by surgery and histological examination, which may have contributed to the implantation in a focus of adenomyosis or uterine trauma. Hegazy et al[16] have reported that in the natural implantation, the trophoblast forms a cytotrophoblast shell to surround the gestational sac, preventing further invasion into myometrium. Intramural pregnancy is more likely to occur in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles, which may be related to the procedure of embryo thawing and the depth of embryo transfer. However, the ET process in this patient was recorded as uneventful each time. ET is routinely performed and monitored by transabdominal ultrasound in our center, and the tip of the ET tube is soft. Thus, the formation of a fistulous tract is unlikely to be related to ET in this case but cannot be excluded.

Intramural pregnancy is difficult to detect due to mild clinical symptoms and the anatomical location of the mass. In the past, intramural pregnancy was not diagnosed until uterine rupture. In recent years, the development of modern transvaginal ultrasound and MRI have been very helpful in visualization of the endometrial-myometrial junction and delineating the association between endometrial and uterine myometrium, which has led to a more accurate diagnosis of intramural pregnancy at an early stage. In a prospective study, Lyu et al[17] demonstrated that 85.5% of women with ectopic pregnancies following IVF-ET were identified by their first pre-surgical transvaginal sonography. It has been reported that MRI has a diagnostic accuracy of 96%[18]. However, the presence of uterine leiomyoma and adenomyosis may affect the diagnosis of intramural pregnancy, and it is difficult to distinguish an intramural pregnancy from gestational trophoblastic disease and interstitial pregnancy[1,19-21]. In our patient, her three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound clearly showed that the mass in the myometrium had a dark area and was surrounded by abundant blood flow signals. In addition, a microscopic sinus tract connected the mass to the uterine cavity. We did not perform MRI to confirm the diagnosis as experienced ultrasound physicians are usually able to make a correct diagnosis using three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound.

Although two women with intramural pregnancy gave birth to live newborn after 30 wk gestation[22,23], the management of patients with intramural pregnancy who wish to maintain pregnancy is extremely difficult and risky. Women who conceive by IVF-ET should be informed of the risk of intramural pregnancy, including uterine rupture, abnormal adherent placenta, hypovolemic shock and hysterectomy, which may have a negative impact on their future fertility. Treatment of intramural pregnancy should be individualized, and depends on its exact location, extent of myometrial involvement, the desire to maintain fertility and when it is diagnosed. It has been reported that uterine rupture and massive hemoperitoneum in intramural pregnancy often occur at 11-30 wk gestation, and hysterectomy is inevitable in most cases[24]. At present, treatment methods mainly include expectant management, surgical enucleation, topical or systemic administration of methotrexate and UAE. One patient with posterior wall intramural pregnancy who had mild symptoms and a β-hCG level of 9.5 mIU/mL opted for expectant management due to her requirement for future fertility[4]. Methotrexate can be administered topically or systemically with or without intracardiac potassium chloride, which can be used alone for expectant treatment or in combination with minimally invasive surgery. Mylene et al[5] suggested that asymptomatic patients with serum β-hCG < 2000 mLU/mL, and a mass diameter < 3 cm should be treated with methotrexate. Wu et al[25] found that patients treated with UAE had a faster recovery of serum β-hCG level, compared to patients treated with methotrexate injection. UAE has the advantages of short operation time, less trauma and quick recovery, but has a high risk of bleeding[6]. Laparoscopic excision surgery has been widely used in the treatment of unruptured intramural pregnancy, but it should be determined whether the mass protrudes outside the uterine cavity. It was reported that a patient underwent hysteroscopic removal of an intramural pregnancy with a sinus tract diagnosed by ultrasound examination[26]. As in the case presented here, the increase in serum β-hCG level should be monitored frequently and this patient underwent an early transvaginal ultrasound examination which resulted in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy at 7 wk gestation. Although a fistulous tract communicating between the endometrial cavity and the mass was observed in our case, we carried out laparoscopic excision as soon as possible as the lesion was protruding from the surface of the uterus and the patient had a desire for future fertility.

We report a case of intramural pregnancy with a microscopic fistula after IVF-ET. Due to the higher incidence of ectopic pregnancy after IVF-ET, we suggest that physicians should be aware of the risk factors for intramural pregnancy and achieve an early diagnosis by closely monitoring serum β-hCG level, and performing transvaginal ultrasound and MRI. For patients with suspected fistulous tract formation in the myometrium diagnosed by three-dimensional ultrasound, more attention should be paid to the depth of the ET tube using transabdominal ultrasound during this process. Appropriate and early selection of treatment is vital to preserve future fertility.

We want to express our thanks to the patient and nurses, doctors, and other medical staff in the Reproductive Center of Women’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University for agreeing to participate in this study.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hegazy AA, Tolunay HE S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Ginsburg KA, Quereshi F, Thomas M, Snowman B. Intramural ectopic pregnancy implanting in adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 1989;51:354-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Boulet SL, Kirby RS, Reefhuis J, Zhang Y, Sunderam S, Cohen B, Bernson D, Copeland G, Bailey MA, Jamieson DJ, Kissin DM; States Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (SMART) Collaborative. Assisted Reproductive Technology and Birth Defects Among Liveborn Infants in Florida, Massachusetts, and Michigan, 2000-2010. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:e154934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lu HF, Sheu BC, Shih JC, Chang YL, Torng PL, Huang SC. Intramural ectopic pregnancy. Sonographic picture and its relation with adenomyosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:886-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bernstein HB, Thrall MM, Clark WB. Expectant management of intramural ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:826-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yao M, Tulandi T. Current status of surgical and nonsurgical management of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:421-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang S, Dong Y, Meng X. Intramural ectopic pregnancy: treatment using uterine artery embolization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:241-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shen Z, Liu C, Zhao L, Xu L, Peng B, Chen Z, Li X, Zhou J. Minimally-invasive management of intramural ectopic pregnancy: an eight-case series and literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hilbert SM, Gunderson S. Complications of Assisted Reproductive Technology. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019;37:239-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ko HS, Lee Y, Lee HJ, Park IY, Chung DY, Kim SP, Park TC, Shin JC. Sonographic and MR findings in 2 cases of intramural pregnancy treated conservatively. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34:356-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ong C, Su LL, Chia D, Choolani M, Biswas A. Sonographic diagnosis and successful medical management of an intramural ectopic pregnancy. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010;38:320-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hamilton CJ, Legarth J, Jaroudi KA. Intramural pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:215-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lyu J, Sun W, Lin Y. Successful Management of Heterotopic Intramural Pregnancy Leading to a Live Birth of the Intrauterine Pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:1126-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ishiguro T, Yamawaki K, Chihara M, Nishikawa N, Enomoto T. Myomectomy scar ectopic pregnancy following a cryopreserved embryo transfer. Reprod Med Biol. 2018;17:509-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Park WI, Jeon YM, Lee JY, Shin SY. Subserosal pregnancy in a previous myomectomy site: a variant of intramural pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:242-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ko JKY, Wan HL, Ngu SF, Cheung VYT, Ng EHY. Cesarean scar molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:449-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hegazy A A. Clinical Embryology for medical students and postgraduate doctors[M]. Little, Brown, 2014. |

| 17. | Lyu J, Ye H, Wang W, Lin Y, Sun W, Lei L, Hao L. Diagnosis and management of heterotopic pregnancy following embryo transfer: clinical analysis of 55 cases from a single institution. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296:85-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ramkrishna J, Kan GR, Reidy KL, Ang WC, Palma-Dias R. Comparison of management regimens following ultrasound diagnosis of nontubal ectopic pregnancies: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2018;125:567-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu Y, Nan F, Liu Z, Wei S, Liu Y, Zhao G, Guan D. Intramural pregnancy: a case report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;176:197-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Su S, Chavan D, Song K, Chi D, Zhang G, Deng X, Li L, Kong B. Distinguishing between intramural pregnancy and choriocarcinoma: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:2129-2132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hafner T, Aslam N, Ross JA, Zosmer N, Jurkovic D. The effectiveness of non-surgical management of early interstitial pregnancy: a report of ten cases and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Petit L, Lecointre C, Ducarme G. Intramural ectopic pregnancy with live birth at 37 wk of gestation. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287:613-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fait G, Goyert G, Sundareson A, Pickens A Jr. Intramural pregnancy with fetal survival: case history and discussion of etiologic factors. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:472-474. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Jin H, Zhou J, Yu Y, Dong M. Intramural pregnancy: a report of 2 cases. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:569-572. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Wu X, Zhang X, Zhu J, Di W. Caesarean scar pregnancy: comparative efficacy and safety of treatment by uterine artery chemoembolization and systemic methotrexate injection. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;161:75-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang J, Xie X. Sonographic diagnosis of intramural pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:2215-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |