Published online Mar 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2637

Peer-review started: October 18, 2021

First decision: December 17, 2021

Revised: December 27, 2021

Accepted: February 10, 2022

Article in press: February 10, 2022

Published online: March 16, 2022

Processing time: 143 Days and 15.3 Hours

Drain-site hernia (DSH) has an extremely low morbidity and has rarely been reported. Small bowel obstruction is a frequent concurrent condition in most cases of DSH, which commonly occurs at the ≥ 10 mm drain-site. Here we report a rare case of DSH at the lateral 5 mm port site one month postoperatively without visceral incarceration. Simultaneously, a brief review of the literature was conducted focusing on the risk factors, diagnosis, and prevention strategies for DSH.

A 76-year-old male patient was admitted to our institution with intermittent abdominal pain and a local abdominal mass which occurred one month after laparoscopic radical resection of rectal cancer one year ago. A computed tomography scan showed an abdominal wall hernia at the 5 mm former drain-site in the left lower quadrant, and that the content consisted of the large omentum. An elective herniorrhaphy was performed by closing the fascial defect and reinforcing the abdominal wall with a synthetic mesh simultaneously. The postoperative period was uneventful. The patient was discharged seven days after the operation without surgery-related complications at the 1-mo follow-up visit.

Emphasis should be placed on DSH despite the decreased use of intra-abdominal drainage. It is recommended that placement of a surgical drainage tube at the ≥ 10 mm trocar site should be avoided. Moreover, it is advisable to have a comprehensive understanding of the risk factors for DSH and complete closure of the fascial defect at the drainage site for high-risk patients.

Core Tip: Drain-site hernia (DSH) is rarely reported at the 5 mm trocar site. In most cases, we prefer to place a large drainage tube at the ≥ 10 mm trocar site and directly remove it postoperatively without any measures to manage the fascial defects, and fail to continuously monitor co-existing disorders which may accelerate DSH formation. These situations may result in the development of DSH in some cases. Here, we report a rare case associated with a literature review to briefly summarize the risk factors, diagnosis, and prevention strategies for DSH.

- Citation: Su J, Deng C, Yin HM. Drain-site hernia after laparoscopic rectal resection: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(8): 2637-2643

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i8/2637.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2637

Drain-site hernia (DSH) is a special type of abdominal incisional hernia. It is rarely reported and may potentially lead to severe consequences both in laparotomy and laparoscopy, such as visceral incarceration and even strangulation. The prevalence of DSH ranges from 0.1% to 3.4% according to the literature[1]. The most critical risk factor related to DSH is still the trocar size, especially those ≥ 10 mm. However, the development of DSH may also be attributed to the following causes, such as improper placement of the intra-abdominal drainage tube, the unstitched fascial defect following removal of the drainage tube and co-existing disorders that may affect fascia healing or increase intra-abdominal pressure. At the same time, there are still insufficient relevant recommendations for managing surgical drains and DSH prevention strategies. Here, we present a rare case of DSH at the lateral 5 mm trocar site. In addition, a literature review was carried out to briefly identify the risk factors, diagnosis, and prevention strategies for DSH.

A 76-year-old male patient [body mass index (BMI), 21.5 kg/m2] was admitted to the General Surgery Department of our institution due to local abdominal distension in the left lower flank and intermittent abdominal pain for one year.

Before admission, the patient had undergone laparoscopic rectal resection one year ago in our institution. During the operation, five trocars were used in this patient, including a 10 mm trocar inserted at the umbilical site, two 5 mm trocars in the left flank, a 12 mm trocar and a 5 mm trocar in the right flank, respectively. Fascia layers were closed by an absorbable suture at the ≥ 10 mm trocar site. A 20 FR soft rubber tube was inserted in the left lower quadrant stoma port to drain excessive blood and exudates. The drainage tube was removed five days postoperatively following gastrointestinal function recovery, and the drainage liquid was ≤ 20 mL/d. The fascia layer at the drain site was not closed due to a tiny defect. The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the ninth day after the operation. The patient reported no discomfort postoperatively. However, one month later, there was abdominal bulging in the left lower flank in the standing position, which disappeared in the supine position. Little attention was paid to this initially; however, the patient felt a gradual progression of the abdominal bulge, accompanied by occasional dull abdominal pain over time.

The patient had a history of chronic bronchitis combined with intermittent cough without regular medical treatment. He also has a history of hypertension, coronary heart disease, and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The patient showed well controlled blood pressure without cardiovascular system symptoms. There were no restrictions on his daily activities.

The patient had no remarkable personal and family history.

According to the physical examination after admission, the patient was found to have a local palpable mass (3 cm in length) in the left lower flank above the former drain-site and an abdominal wall defect (2 cm in length). Tenderness and rebound tenderness were not observed in the abdomen.

Routine serological examinations were performed without obvious abnormalities.

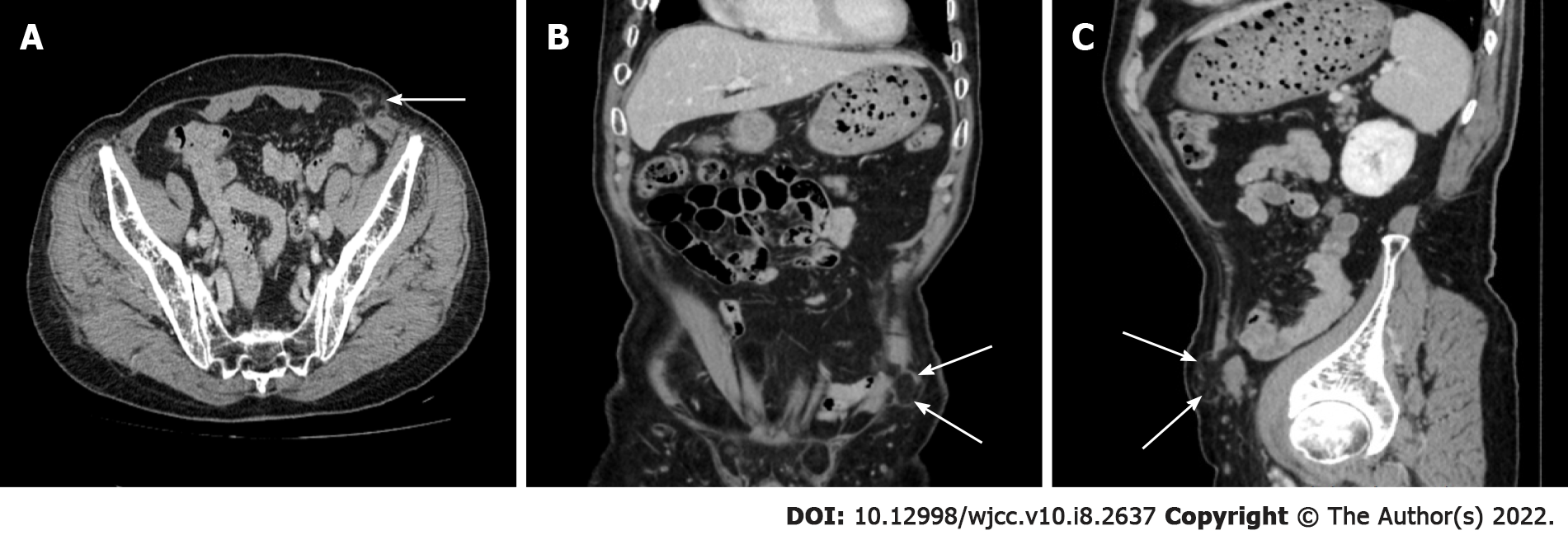

A preoperative computed tomography scan confirmed the diagnosis and showed an abdominal wall hernia at the drainage site in the left lower quadrant, and the content consisted of the omentum majus (Figure 1). The detected abdominal wall fascial defect was 2 cm in diameter.

The clinical manifestations and auxiliary examinations carried out in this patient confirmed the diagnosis of left lower abdominal DSH.

An elective herniorrhaphy was performed with intraoperative discovery of partial omentum entrapped in the abdominal wall defect, close to the subcutaneous tissue layer. Ischemic necrosis of the omentum was not found. We released the adhesive omentum and put it back into the abdominal cavity, and adopted the Sublay repair of the hernia. The fascial defect was continuously closed with a slowly-absorbable suture, and a polypropylene mesh prosthetic was applied to strengthen the abdominal wall.

The patient recovered well during the postoperative period and was discharged seven days after the operation. Follow-up of the patient one month postoperatively revealed no surgery- or mesh-related complications.

DSH is a special type of trocar site hernia (TSH). TSH is widely recognized to be divided into three types based on clinical characteristics and onset time[2]. Specifically, the early-onset type appears at a very early stage after surgery, usually presenting as small bowel obstruction. The late-onset type develops several weeks after surgery or even later, with the manifestation of local abdominal bulging without visceral incarceration. While the special type that arises immediately after surgery involves postoperative dehiscence of the whole abdominal wall.

As suggested in a previous retrospective study by Nacef et al[3], the trocar size is the dominant risk factor for TSHs. TSHs usually occur in the umbilical incision position, especially when the trocar size is ≥ 10 mm. It has been reported that over 82% of TSHs occurred at the umbilicus site, with an extremely high rate of 96% when the trocar size was larger than 10 mm[4]. In addition, the prevalence of TSH can be further increased when the fascial defect at the trocar site is not sutured. It is commonly acknowledged that a non-bladed trocar can decrease tissue trauma, resulting in the reduced incidence of TSH[5]. A TSH can also occur at the non-bladed trocar site. As a result, it is highly recommended that the port ≥ 10 mm in size should be sutured regardless of the designed scheme of the trocar[6,7]. Accumulated data has been reported concerning the occurrence of TSH at the 8 mm trocar site with the application of robotic techniques in abdominal surgery[8]. However, the occurrence of TSH at 5 mm and 3 mm trocar sites is rarely reported, and preoperative weakness or defects in the fascia plane at the trocar site and excessive manipulation at the trocar site can both raise the risk of TSH. In order to prevent TSH, it is practicable to apply early detection and effective intraoperative measures to reinforce the fascia layer[9]. Some additional risk factors related to TSH include advanced age, gender (female), obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2 ), diabetes mellitus, enlargement of incision, infection, prolongation of operative time, co-existence of hernia, unstitched fascia planes, insufficient muscle relaxation before trocar removal, etc. However, the most critical factors are still the trocar size, and obesity[10].

Similar to the mechanisms of TSH mentioned above, most DSHs occur at the ≥ 10 mm port site. Manigrasso et al[11] reported a case of DSH at a 10 mm port site in the right lower quadrant before the drainage tube was removed. This was partially attributed to the inappropriate insertion of an intra-abdominal drain to a large port site. Similarly, Gao et al[12] described a DSH case which occurred at the 10 mm port site in the left lower quadrant within a short time after the removal of a drainage tube. The pivotal reasons were obesity of the patient and an unstitched fascial defect. Both cases described above underwent emergency surgery due to small bowel incarceration. However, there are rare reports of DSH at the 5 mm port site. Moreaux et al[13] and James et al[14] reported cases which occurred at the 5 mm port site from several hours to several days after the drainage tube was removed. These cases were largely caused by the suction effect resulting from drain removal and a postoperative complication (e.g., respiratory tract infection), respectively. Furthermore, the majority of DSH cases that occurred several weeks to several months after surgery commonly had concurrent visceral incarceration, such as Richter hernias or appendix trapping to the former drain-site[15,16].

With regard to the case reported herein, the DSH occurred at the 5 mm drain-site in the left lower quadrant, not at the ≥ 10 mm port site and close to the linea alba, and without viscera obstruction. The patient also had no relevant risk factors (e.g., obesity, bladed trocar, prolonged operation time, wound infection, postoperative complications, etc.) mentioned previously. Moreover, no consensus has been reached on whether the fascial defect after drainage tube removal at the 5 mm port site requires suturing[11]. The exact mechanism of DSH in our case is uncertain according to current research.

Indeed, we propose the classification of DSH into three types according to the onset time of hernia and the removal status of the drainage tube. Specifically, the first type occurs several hours to several days after the surgical procedure without drainage tube removal, which is characterized by a visceral hernia to the free space between abdominal wall and drainage tube or visceral incarceration to the side hole of the drainage tube. The contents generally consist of omentum, small bowel, mesentery, and appendix[11,17,18]. The second type occurs immediately or several hours to several days after removal of the drainage tube, with viscera (e.g., small bowel, omentum, appendix, fallopian tube, and gallbladder) incarceration to the residual cavity at the drainage port in most cases[19-23]. The third type can develop several weeks to several months or later after surgery, which features local abdominal distension at the drainage port, with or without visceral incarceration[15,24]. The incidence of the third type has been reported to be almost twice that of the other two types[1].

Moreover, the potential risk of each type of DSH was summarized in our study following in-depth analysis of the current literature. The predominant cause of the first type is a port size larger than the drainage tube, producing additional space between the tube and abdominal wall. Viscera such as small bowel and mesentery may be herniated to the hiatal region with a sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure when the patient suffers acute pain, cough, nausea, and vomiting[11,18]. Besides, due to the larger quantity or size of the side holes of the tube, a huge-caliber tube may contribute to bowel obstruction. In such circumstances, there may be a higher risk of incarceration or attachment of small bowel and mesentery to the side holes, resulting in bowel canal angulation. In addition, the suction effect after air decompression without clamping the tube is another vital reason for DSH[17]. The second type occurs partly due to aggressive tube extraction. Severe pain may raise intra-abdominal pressure and squeeze the small bowel to herniate to the remnant cavity at the drainage site. In these cases, high abdominal pressure is an essential cause in the development of DSH[22]. Other risk factors that affect fascia healing, such as malnutrition, obesity, metabolic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus), and chemotherapy, may also contribute to DSH[25]. For the third type, the unstitched fascial defect and co-existence of some disorders that may affect the healing of fascial tissue and the gradually increased intra-abdominal pressure may promote the formation of DSH. Therefore, possible reasons for DSH in our patient might be the uncontrolled chronic bronchitis that caused frequent coughing leading to high intra-abdominal pressure, as well as the unstitched fascial defect at the drainage site. As a result, it is recommended that the 5 mm drain-site fascial defect should be sutured under such conditions and the simultaneous management of comorbidities.

The typical manifestations of DSH are abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diffuse or local abdominal distension, as well as obstructed passage of stool and flatus. Significantly, an asymptomatic hernia can also occur in a few people without symptoms except an inconspicuous abdominal mass. An emergency ultrasound, abdominal X-ray, gastrointestinal radiography and abdominal CT scan should be scheduled to confirm DSH. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scanning is particularly crucial to display the position of the visceral hernia, and the identification of concurrent bowel canal incarceration, strangulation, and necrosis[26].

When DSH is diagnosed, an emergency operation or an elective surgical approach should be performed according to its classification and the presence of concurrent visceral incarceration. The early-onset DSH (including the first and the second types, as mentioned above), with bowel obstruction as the primary manifestation, usually requires immediate exploratory surgery. There is a need to perform fascial defect closure as well as standard bowel resection and anastomosis in the case of visceral necrosis. The late-onset DSH (the third type) is frequently accompanied by an abdominal mass alone, without visceral incarceration. The traditional therapeutic choice is elective herniorrhaphy. At present, this operation is still the cure for DSH. A retrospective study[21] on laparoscopic procedures for children revealed that 5/148 had DSH after the operation, three of which were released by sedation. These cases had the potential danger of viscera strangulation. Accordingly, we advocate emergency procedures once visceral incarceration is confirmed in cases of necrosis. In addition, whether a mesh repair is needed depends on abdominal defect caliber, BMI, and the co-existence of other risk factors leading to DSH[27]. For some complex incision hernias, dual-layer sandwich repair for abdominal reconstruction can efficiently reduce the recurrence rate of hernia[28].

We believe that precautionary measures and strategies are available to prevent and reduce the occurrence of DSH based on the risk factors mentioned above. The first issue is to be more prudent regarding routine abdominal drainage. The purpose of surgical drainage is to decrease liquid (e.g., ascites, blood, inflammatory exudates, etc.) accumulation and remove gastrointestinal juice in the case of anastomotic fistula. Surgical drainage can potentially induce all types of postoperative complications, such as intra-abdominal or wound infection, adhesions, bowel canal erosion, aggravated abdominal pain, respiratory suppression, bleeding, anastomotic ruptures, etc[29]. Improper placement of drainage, however, can lead to the formation of DSH to some extent. Therefore, it is recommended that the necessity and harm of abdominal drainage in clinical practice should be seriously considered. Nowadays, an increasing number of experts recommend irregular insertion of abdominal drainage tubes with the application of laparoscopic techniques and innovation of surgical procedures, especially in laparoscopic gynecological surgery and laparoscopic cholecystectomy[1,15,17]. Secondly, it is recommended that there should be reasonable consideration regarding the selection and insertion position of the drainage tube. Insertion of surgical drainage should be avoided at the ≥ 10 mm trocar site to eliminate the free space between the abdominal wall and the tube. The residual unstitched huge fascial defect after tube removal is prone to causing visceral incarceration[11]. Therefore, it is advisable to insert the tube into the pelvic cavity to keep it away from the small intestine. In addition, a Z-shaped or oblique insertion can avoid a straight tunnel, thus reducing intra-abdominal viscera bulging[15,18,30]. In addition, it is better to use tubes with a smaller caliber, fewer and diminutive side holes if needed. Simultaneously, in order to prevent the suction effect, the drainage tube should remain clamped until the completion of air decompression[17]. Thirdly, a more scientific practice is advisable to remove the drainage tube. Aggressive drain extraction inevitably aggravates wound pain and increases intra-abdominal pressure, as well as the rate of visceral injury and bleeding. Therefore, it is better to remove the drainage tube gradually, rather than aggressively. It is strongly recommended to conduct a clockwise or counterclockwise rotation of the tube until free from the adhesion before removal of the drainage tube. In addition, sedation and analgesia should be considered in some cases[21]. Fourthly, fascial defects should be sutured appropriately after removal of the drainage tube, especially defects ≥ 10 mm in diameter. Fascial defect closure at the 8 mm drain site would also be beneficial to patients. There are various available approaches used for suturing, such as a single intermittent suture, continuous suture, purse-string suture and total layers suture[12,15]. However, no consensus has been reached at present with regard to whether the drainage site of 5 mm in diameter should be closed. The group supporting no-closure assumed that the incidence of hernia at the 5 mm port site was extremely low with no requirement for closure[31]. While those who suggested closure supposed that prolonged operative times and excessive manipulation could expand the fascial incisions, which, in turn, increased the occurrence rate of hernia[32]. In our opinion, patients may benefit from fascia closure at the 5 mm drainage site when such patients have one or more risk factor(s) for DSH. Lastly, the overall management of comorbidities is of crucial importance. Hernias may still occur in some cases, even if the fascia at the port site has been sutured. These people, in general, have co-existing disorders that may affect healing of the fascial incision or increase the intra-abdominal pressure, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, constipation, obesity and benign prostatic hyperplasia[25]. Strategically, multidisciplinary treatment may benefit the formulation of an individualized treatment schedule that is convenient for whole-process supervision of the physical condition of patients. Collectively, a comprehensive and profound understanding of the risk factors for DSH and the application of adequate precautions are thought to decrease the incidence of DSH to a minimum.

DSH is rare in the clinical setting. There is a need to pay enough attention to its disastrous complications. Unnecessary placement of a drainage tube should still be eliminated despite the reduced application of intra-abdominal drain placement with the advent of minimally invasive surgery, and an overall understanding of the complications of postoperative drainage. However, drainage is still needed after surgery for patients with infections and those who are prone to fistulas. In such circumstances, it is recommended that inserting a drainage tube at the ≥ 10 mm trocar site should be avoided and advisable, scientific, and practical measures taken to manage intra-abdominal drains. In addition, it is of great significance to have a better understanding of the risk factors for DSH, and complete closure of fascial defects at the drainage site for those high-risk groups, in order to decrease the incidence of DSH.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cianci P, Manigrasso M S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Makama JG, Ameh EA, Garba ES. Drain Site Hernia: A Review of the Incidence and Prevalence. West Afr J Med. 2015;34:62-68. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Tonouchi H, Ohmori Y, Kobayashi M, Kusunoki M. Trocar site hernia. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1248-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Nacef K, Chaouch MA, Chaouch A, Khalifa MB, Ghannouchi M, Boudokhane M. Trocar site post incisional hernia: about 19 cases. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;29:183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Helgstrand F, Rosenberg J, Bisgaard T. Trocar site hernia after laparoscopic surgery: a qualitative systematic review. Hernia. 2011;15:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Gutierrez M, Stuparich M, Behbehani S, Nahas S. Does closure of fascia, type, and location of trocar influence occurrence of port site hernias? Surg Endosc. 2020;34:5250-5258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kouba EJ, Hubbard JS, Wallen E, Pruthi RS. Incisional hernia in a 12-mm nonbladed trocar site following laparoscopic nephrectomy. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:2399-2402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chiong E, Hegarty PK, Davis JW, Kamat AM, Pisters LL, Matin SF. Port-site hernias occurring after the use of bladeless radially expanding trocars. Urology. 2010;75:574-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Uketa S, Shimizu Y, Ogawa K, Utsunomiya N, Kanamaru S. Port-site incisional hernia from an 8-mm robotic trocar following robot-assisted radical cystectomy: Report of a rare case. IJU Case Rep. 2020;3:97-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bergemann JL, Hibbert ML, Harkins G, Narvaez J, Asato A. Omental herniation through a 3-mm umbilical trocar site: unmasking a hidden umbilical hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001;11:171-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nofal MN, Yousef AJ, Hamdan FF, Oudat AH. Characteristics of Trocar Site Hernia after Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Sci Rep. 2020;10:2868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Manigrasso M, Anoldo P, Milone F, De Palma GD, Milone M. Case report of an uncommon case of drain-site hernia after colorectal surgery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:500-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gao X, Chen Q, Wang C, Yu YY, Yang L, Zhou ZG. Rare case of drain-site hernia after laparoscopic surgery and a novel strategy of prevention: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:6504-6510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Moreaux G, Estrade-Huchon S, Bader G, Guyot B, Heitz D, Fauconnier A, Huchon C. Five-millimeter trocar site small bowel eviscerations after gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:643-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | James M, Senthil G, Kalayarasan R, Pottakkat B. A case of unusual evisceration through laparoscopic port site. J Minim Access Surg. 2021;17:559-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gass M, Zynamon A, von Flüe M, Peterli R. Drain-site hernia containing the vermiform appendix: report of a case. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:198783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Owens M, Barry M, Janjua AZ, Winter DC. A systematic review of laparoscopic port site hernias in gastrointestinal surgery. Surgeon. 2011;9:218-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Poon CM, Leong HT. Abdominal drain causing early small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic colectomy. JSLS. 2009;13:625-627. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Falidas E, Mathioulakis S, Vlachos K, Pavlakis E, Villias C. Strangulated intestinal hernia through a drain site. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tidjane A, Tabeti B, Boudjenan Serradj N, Bensafir S, Ikhlef N, Benmaarouf N. Laparoscopic management of a drain site evisceration of the vermiform appendix, a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;42:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Saini P, Faridi MS, Agarwal N, Gupta A, Kaur N. Drain site evisceration of fallopian tube, another reason to discourage abdominal drain: report of a case and brief review of literature. Trop Doct. 2012;42:122-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ramalingam M, Senthil K, Murugesan A, Pai M. Early-onset port site (drain site) hernia in pediatric laparoscopy: a case series. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:416-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kadija S, Sparić R, Zizić V, Stefanović A. [Drainage as a rare cause of intestinal incarceration]. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2005;133:370-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vedat B, Aziz S, Cetin K. Evisceration of gallbladder at the site of a Pezzer drain: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:8601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Makama JG, Ahmed A, Ukwenya Y, Mohammed I. Drain site hernia in an adult: a case report. West Afr J Med. 2010;29:429-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Loh A, Jones PA. Evisceration and other complications of abdominal drains. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67:687-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chorti A, AbuFarha S, Michalopoulos A, Papavramidis TS. Richter's hernia in a 5-mm trocar site. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X18823413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lambertz A, Stüben BO, Bock B, Eickhoff R, Kroh A, Klink CD, Neumann UP, Krones CJ. Port-site incisional hernia - A case series of 54 patients. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;14:8-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hicks CW, Poruk KE, Baltodano PA, Soares KC, Azoury SC, Cooney CM, Cornell P, Eckhauser FE. Long-term outcomes of sandwich ventral hernia repair paired with hybrid vacuum-assisted closure. J Surg Res. 2016;204:282-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Wong Y, Ng IO, Lam CM, Poon RT, Wong J. Abdominal drainage after hepatic resection is contraindicated in patients with chronic liver diseases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:194-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | O'Riordan DC, Horgan LF, Davidson BR. Drain-site herniation of the appendix. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liot E, Bréguet R, Piguet V, Ris F, Volonté F, Morel P. Evaluation of port site hernias, chronic pain and recurrence rates after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: a monocentric long-term study. Hernia. 2017;21:917-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pereira N, Hutchinson AP, Irani M, Chung ER, Lekovich JP, Chung PH, Zarnegar R, Rosenwaks Z. 5-millimeter Trocar-site Hernias After Laparoscopy Requiring Surgical Repair. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:505-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |