Published online Mar 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2629

Peer-review started: October 20, 2021

First decision: December 17, 2021

Revised: December 29, 2021

Accepted: February 10, 2022

Article in press: February 10, 2022

Published online: March 16, 2022

Processing time: 141 Days and 16 Hours

Symptomatic urachal anomalies are rare disorders. The management of urachal remnants has historically been surgical excision because of the connection between urachal remnants and risk of malignancy development later in life. However, recent literature suggests that urachal anomalies that do not extend to the bladder can be treated with conservative management. In this case, we report a newborn with an infected urachal remnant who was treated with a combination of antibiotics and a silver-based dressing and finally recovered well.

Female baby A, weighing 2.88 kg at 38+5 wk of gestational age, was referred to the hospital because of a red, swollen umbilicus approximately 2 cm × 2 cm in size with yellow purulent exudate. Through physical and ultrasound examination, the baby was finally diagnosed with a urachal anomaly. We first used oxacillin to prevent infection for 3 d. On the 4th day, microbiology testing of the umbilical exudate revealed the presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). We changed the treatment with oxacillin to vancomycin for systemic infection and treated the umbilical inflammation with a silver sulfate dressing. After 5 d, the symptoms of the umbilicus disappeared, and we discontinued silver dressing application. On the 12th day, umbilical exudate testing was negative for MRSA. On the 14th day, the baby's blood testing showed a white blood cell count of 14.7 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage of 27.8%, and C-reactive protein level of 1.0 mg/L, suggesting that the infection had been controlled. We stopped treatment, and the baby was discharged with no complications. In this case, the infected urachal anomaly was cured with silver dressing and antibiotic application instead of surgical methods, which was a different course from that of some other urachal remnant cases.

Anomalies that do not connect with the bladder can be treated with nonoperative management, including application of conservative antibiotics and local intervention with silver-based dressings. Silver sulfate dressings are absolutely safe for neonates with judicious use, and they play an established role in preventing infection without resistance, which is a common problem with other antibiotics and antiseptics.

Core Tip: Immediate surgical excision of urachal remnants has been generally recommended before. However, patients suffer multiple postoperative complications, resulting in re-operation. Recently, accumulating evidence has indicated that a nonoperative approach may be a safe, reasonable alternative to surgical intervention, especially in patients under 6 mo old. Here, we report a case of urachal anomaly with infection that managed with non-surgical therapy, including: Infection control, wound management and nutrition support. After 2 wk, umbilical symptoms fully recovered. Reoccurring symptoms were not found during follow-up.

- Citation: Shi ZY, Hou SL, Li XW. Silver dressing in the management of an infant's urachal anomaly infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(8): 2629-2636

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i8/2629.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2629

The urachus is a connection between the fetal bladder and the allantois. With the descent of the bladder toward the pelvis, the urachus is stretched, finally leading to obliteration of its lumen[1]. On rare occasions, the process of obliteration is incomplete, resulting in urachal remnants (URs). There are four types of urachal anomalies: patent urachus, urachal sinus, urachal cyst, and vesicourachal diverticula[2]. According to previous reports, URs occur in 1.6% of children under 15 years old[3], and the incidence of infant urachal anomalies is less than 1/150000[4], which is very rare. Urachal cysts are the most commonly reported anomaly, while sinuses are 2th in frequency[5]. Ultrasound is often used as the primary imaging diagnostic tool for urachal anomalies[5]. However, there is no consensus or guideline on the management of URs. Many studies have reported that remnants may lead to inflammation, infection, umbilical discharge, and even abdominal pain, pelvic disease or malignancy at later ages if the URs are not removed[2,6,7]. Thus, immediate surgical excision of URs has previously been generally recommended[6,8].

However, surgical excision has been suggested to be perhaps too aggressive because several studies have shown that some children with surgical lesions do not benefit from prophylactic excision. In addition, the risk of urachal cancer is vanishingly remote among those with URs. In contrast, patients suffer multiple postoperative complications, resulting in reoperation[3,9]. Recently, accumulating evidence has indicated that a nonoperative approach may be a safe, reasonable alternative to surgical intervention, especially in patients under 6 mo old[3]. Use of silver dressings for acute and chronic open wounds has been advocated. Most silver dressings are bactericidal and fungicidal and are especially effective against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). MRSA is one of the most important gram-positive bacteria causing hospital infections, and it is resistant to commonly used antibiotics. Here, we report a case of a urachal anomaly with MRSA infection managed with antibiotics and silver dressings.

The patient was admitted to the hospital with umbilical swelling and exudate beyond 4 d.

Female baby A, weighing 2.88 kg at 38+5 wk of gestational age, was referred to the hospital because of a red, swollen umbilicus with yellow purulent exudate, paroxysmal crying and decreased milk intake.

Cefaclor was taken orally 2 d before admission, but the umbilical symptoms did not improve and were accompanied by progressively increased secretions.

Female baby A was delivered by cesarean section at 38+5 wk gestational age to a gravida 1 para 1 mother. Complications during pregnancy and infant Apgar scores were unclear.

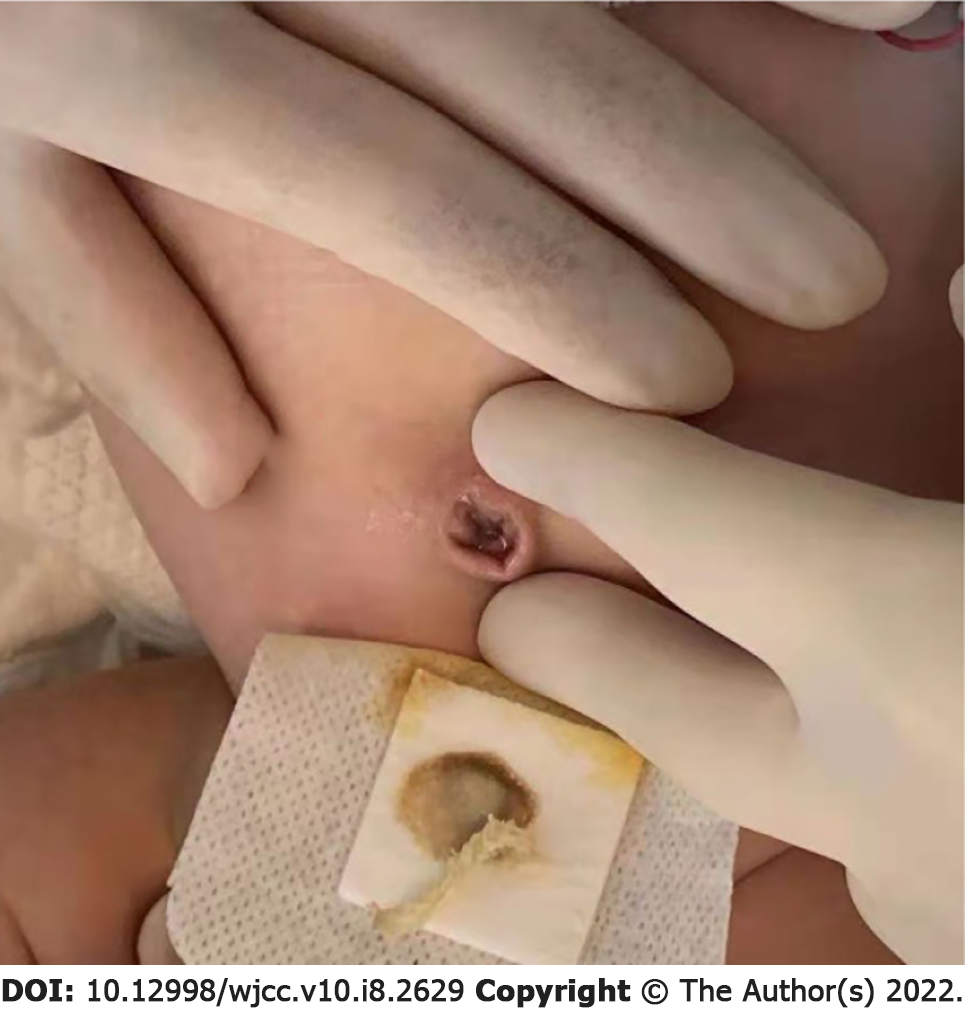

Physical examination revealed a manifestation of maturity, sensitive reaction, variegation all over the body, no fever, and umbilical swelling approximately 3 cm × 3.5 cm in size with yellow purulent umbilical urinary discharge (Figure 1). A tract into the umbilicus was observed, approximately 2 cm in length. No urine overflowed, and no stool was discharged from the baby's umbilicus.

On the day of admission, her blood count showed a white blood cells (WBC) count of 18.9 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage of 32.2%, hemoglobin (HGB) level of 116 g/L, platelet count of 445 × 109/L, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 22.0 mg/L. Biochemistry showed blood glucose level of 9.0 mmol/L and procalcitonin (PCT) level of 0.17 ng/mL. On the 2th day after admission, cerebrospinal fluid testing was positive, with a protein count of 776 mg/L, red blood cell count of 110 × 106/L, chloride level of 122 mmol/L, and glucose level of 3.30 mmol/L. On the 3th day, the WBC count was 16.1 × 109/L, the neutrophil percentage was 29.4%, the HGB level was 114 g/L and the CRP level decreased to 11.2 mg/L. On the 4th day, microbiology of the umbilical exudate revealed the presence of MRSA. On the 6th day, the drug concentration of vancomycin was 10.3 µg/mL. On the 13th d after admission, the blood count showed a WBC count of 14.7 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage of 27.8%, and CRP level of 1.0 mg/L, and baby was finally discharged.

On the 2th day after hospitalization, ultrasonography (US) images showed a fluid-filled uneven hypoechoic structure just below the navel at a distance of 1.5 cm, and a weak point-like echo flow could be seen with no connection to the bladder.

The patient was eventually diagnosed with an infected urachal anomaly: Urachal sinus.

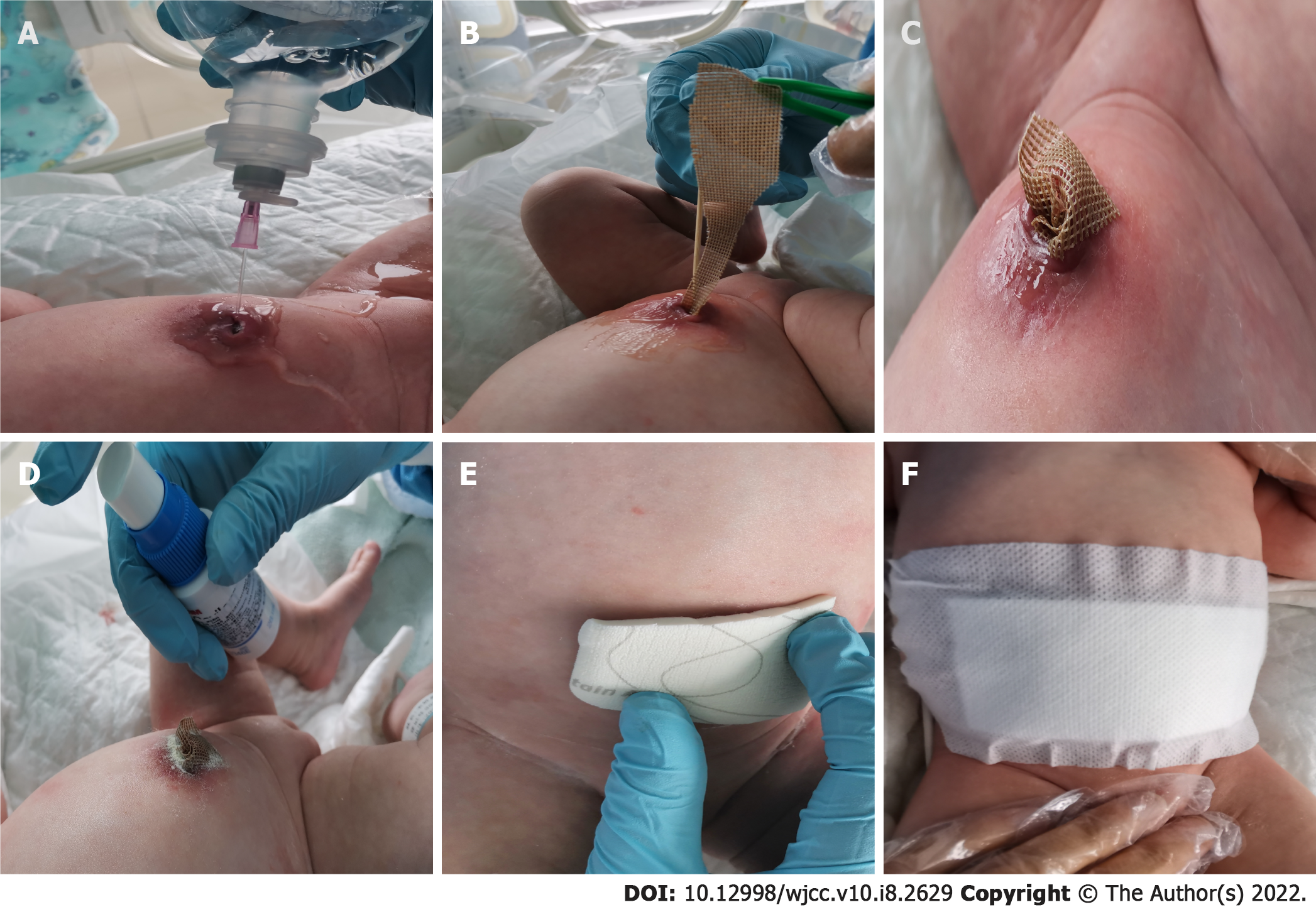

Before US examination, it was unclear whether there was a sinus tract connected to the abdomen. During this period, we kept the umbilicus clean and dry using iodine as a skin disinfectant. After US examination suggested that there was a blind end within the umbilicus and bladder, we provided the following treatment: (1) Infection control: Empirical antibiotics (oxacillin) were administered for 3 d. When the umbilical secretion culture suggested positivity for MRSA, we then implemented contact isolation for this baby and changed the oxacillin to vancomycin as a systemic antibiotic for 2 wk; (2) Wound management: When microbiology of umbilical exudate revealed the presence of MRSA, we managed the umbilical infection with topical silver sulfate dressings. Aseptic operation was strictly obeyed before using silver sulfate dressings. The dressing change process was as follows (Figure 2): First, we rinsed the umbilicus and sinus with a warm 0.9% sodium chloride solution after visible blinding on US was confirmed. A silver dressing was lightly packed into the sinus, and no-sting barrier film was sprinkled to protect the periumbilical skin. Finally, the samples were covered with foam dressings and sterile gauze locally on the red, swollen umbilical area, to absorb exudate. We continued silver dressing application for 5 d and changed the dressing every 2-3 d according to exudate volume. When signs of umbilical inflammation decreased and symptoms of a red, swollen umbilicus disappeared, we stopped using the silver sulfate dressings; and (3) Nutrition support: An intravenous infusion of 10% glucose was provided along with premium powdered formula. With the above-described treatment, the symptoms of the umbilicus were alleviated after 14 d, and the patient was discharged.

On the 8th day of hospitalization, the infant’s umbilical cord had completely healed without redness, swelling or exudation (Figure 3). On the 9th day, the US image showed no liquid occupancy. On the 14th day after hospitalization, the infection indicators decreased, umbilical symptoms fully dissipated, and the baby was discharged (Figure 4). Reoccurring urachus anomaly symptoms were not found during the 3 m follow-up by US.

Asymptomatic URs present in as much as 2% of the general population. Symptomatic URs always manifest as urachal sinus, urachal fistula, urachal cyst or urachal diverticulum, and all of these manifestations can be complicated with infection[10]. Infected URs present with local signs and symptoms such as purulent drainage, warmth, abdominal pain, erythema and other abnormal appearances of the umbilicus[8,11]. The first and most common presentation of infected URs is periumbilical inflammation, which is consistent with our case. Yellow umbilical urinary discharge was also observed in this case, which is also consistent with previous reports. However, we did not find urinary retention or irritative voiding through physical examination, differing from other series. URs have also been reported to present with some rare manifestations, such as bowel and ureteral obstruction[12] and peritonitis[13]. However, we did not find these severe symptoms in this case. Infected URs present with or without laboratory evidence of infectious processes[14]. In our case, a positive wound culture was predictive of the underlying infectious process. Staphylococcus is reported as the predominant skin-related organism, which suggests that the genitourinary tract is neither the source of infection nor likely infected by the kidney or bladder[8].

Urachal diagnostic guidelines are currently lacking. Urachal disorders are always reliably diagnosed by history taking and US examination, voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), computed tomography and fistulography[15]. US is recommended as the primary imaging method because of its shorter turnaround time and lack of exposure to radiation and because it is easily accessible[9]. In the detection of urachal anomalies by US, a positive predictive value of 83% and a sensitivity of 79% have been found[5]. Choi et al[8] reported that US was diagnostic in 100% of urachal cysts. VCUG is an invasive procedure, adding additional cost, which is inconvenient for infants[14]. Fistulography is suggested to distinguish vitelline duct remnants from urachal remnants[8]. In our case, urachal anomaly was confirmed by clinical symptoms and US findings. Umbilical serous drainage and periumbilical erythema were noticed by physical examination. US scanning revealed the presence of a urachal sinus.

In the case of URs, there is debate regarding optimal management. Few reports have provided guidelines for therapeutic approaches in children, but these approaches remain controversial[16]. Surgical intervention has historically been the standard of care for patients with URs. However, side effects such as wound infection and bladder leakage have been found after surgical excision. Dethlefs et al[9] retrospectively reviewed 103 pediatric patients diagnosed with a UR and found that postoperative complications occurred in 14.7% of patients who underwent UR excision and that 1 patient underwent reoperation because of bladder leakage. Choi et al[8] reported 1 postoperative wound infection and 1 bladder leakage case among 26 UR cases. In contrast, other nonoperative URs resolved without recurrent symptoms.

UR excision has been advised to preventing the risk of malignant transformation later in life. However, it has been suggested that there is no association between URs in early childhood and later urachal carcinoma[17]. Surgical resection should be restricted to children older than 1 year with multiple clinical episodes[10]. Recently, conservative management has been advocated for children who are diagnosed with URs that are disconnected from the bladder within the 1th year of life[2]. Studies have reported that urachuses often involve spontaneous presentation within the first year of birth along with complete resolution of symptoms after nonoperative management, which differs from the case for adults, who require necessary surgical intervention[10,16,18]. Lipskar et al[16] reported 7 urachal anomalies treated with nonoperative management. Three infected urachal cysts were initially managed with antibiotics and then percutaneous drainage of abscesses guided by radiology. In a 2014 retrospective study including 27 patients, the authors preferred a conservative strategy, restricting the surgical option for a persistent patent urachus case and two reinfections of unsolved urachal cyst cases[19]. Other studies have also recommended a conservative approach for children under 1 year old, and nonoperative treatment did not adversely affect the overall outcome[6]. In conclusion, the management of URs has shifted toward nonoperative approaches, including antibiotic treatment and radiographic monitoring. However, evidence of nonoperative management is still limited.

Systemically administered antibiotics are used for invasive infection, and topical antibacterials are used for an open surface wound. There are different available dressings impregnated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as neomycin, polymyxin and mupirocin. However, these dressings risk allergy and resistance development[20]. Current evidence supports the use of silver dressings to decrease the bacterial load in wounds of adult and pediatric populations. Most silver dressings can be used in acute and chronic open wounds because they are bactericidal and fungicidal and are especially effective against resistant organisms such as MRSA. In addition, silver exerts an antimicrobial effect in the presence of wound exudate. Previous studies have shown that topical silver may kill MRSA. Case studies[21,22] have demonstrated that silver dressings can be used to manage local MRSA infections in surgical revision wounds. Silver dressings can reduce the need for systemic antibiotics or even clear bacteria successfully without the use of systemic antibiotics in some patients. However, the use of silver-containing products in infants has not been evaluated rigorously. Thus, silver toxicity should be considered[23].

Few studies have included the use of silver dressings to control local infections of urachal anomalies. Galati et al[17] reported only 1 patient that underwent surgical excision among 9 urachal sinus patients after initial management consisting of local intervention with sulfate nitrate and management of local infection. However, silver nitrate was reported to be proinflammatory and to possibly cause staining[24]. In this case, we proposed that infected UR could be managed with antibiotics for general infection and local intervention with silver sulfate dressings for umbilical inflammation, without any complications related to the silver dressings. Through follow-up US scanning after discharge, we found that the child did not experience any other symptoms of urachal anomalies. The urachal tract regressed according to clinical and US monitoring. Thus, we hypothesized that antibiotics along with topical agents may be an alternative therapeutic option for infected URs. Other varieties of silver dressings have also been reported in treating skin breakdown in preterm infants and have achieved a good effect[25,26]. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, it is recommended to change dressings as often as required, at least once 1 wk, depending on the clinical status of the wound and exudate volume[27]. Some scholars have suggested that silver dressing use should be limited to no longer than 2 consecutive weeks because of silver toxicity. Principles of wound management in pediatric patients in the UK recommend application of silver dressings for 2-4 wk in infants[23]. In this case, we applied silver dressings for up to 5 d and changed them every 2-3 d, according to umbilical drainage and clinical status. Once umbilical drainage stopped, we discontinued silver dressing application in case of silver toxicity or other potential effects. As a result, the neonate recovered well, without any adverse effects. At 3 m of follow-up, no recurrent symptoms were observed.

Urachal anomaly is a rare disorder that has historically required surgical management. In anomalies that do not extend to the bladder, a conservative option may be an alternative. Antibiotic treatment is usually advocated in fighting systemic infection. In some special cases, topical medicines are needed to prevent local inflammation. Among a variety of antimicrobial dressings, silver-based dressings play a major role against microorganisms. Silver sulfate has not been reported to have any related complications. Thus, we concluded that appropriate use of silver sulfate dressings may be safe and successful in managing MRSA-infected URs in neonates. However, there are still some limitations. For example, there is insufficient and inadequate evidence proving the safe duration of silver dressings for the treatment of URs.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Nursing

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Apiratwarakul K, Shariati MBH S-Editor: Guo XR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo XR

| 2. | Siow SL, Mahendran HA, Hardin M. Laparoscopic management of symptomatic urachal remnants in adulthood. Asian J Surg. 2015;38:85-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Monagle P, Chan AKC, Goldenberg NA, Ichord RN, Journeycake JM, Nowak-Göttl U, Vesely SK. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e737S-e801S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 933] [Cited by in RCA: 1025] [Article Influence: 78.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu G, Zhou J, Yang FW, Yang C, Song ZY, Liang CZ. Urachal cyst with infection was misdiagnosis as torsion of ovarian cyst pedicle in children: a case report and literature review. Zhonghua Qiangjing Waike Zazhi. 2020;13:250-252. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Luo X, Lin J, Du L, Wu R, Li Z. Ultrasound findings of urachal anomalies. A series of interesting cases. Med Ultrason. 2019;21:294-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hassanbhai DH, Ng FC, Koh LT. Is excision necessary in the management of adult urachal remnants? Scand J Urol. 2018;52:432-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sato H, Furuta S, Tsuji S, Kawase H, Kitagawa H. The current strategy for urachal remnants. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015;31:581-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Choi YJ, Kim JM, Ahn SY, Oh JT, Han SW, Lee JS. Urachal anomalies in children: a single center experience. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47:782-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dethlefs CR, Abdessalam SF, Raynor SC, Perry DA, Allbery SM, Lyden ER, Azarow KS, Cusick RA. Conservative management of urachal anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1054-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Tazi F, Ahsaini M, Khalouk A, Mellas S, Stuurman-Wieringa RE, Elfassi MJ, Farih MH. Abscess of urachal remnants presenting with acute abdomen: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Copp HL, Wong IY, Krishnan C, Malhotra S, Kennedy WA. Clinical presentation and urachal remnant pathology: implications for treatment. J Urol. 2009;182:1921-1924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Iuchtman M, Rahav S, Zer M, Mogilner J, Siplovich L. Management of urachal anomalies in children and adults. Urology. 1993;42:426-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Qureshi K, Maskell D, McMillan C, Wijewardena C. An infected urachal cyst presenting as an acute abdomen - A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:633-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yapo BR, Gerges B, Holland AJ. Investigation and management of suspected urachal anomalies in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:589-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Parada Villavicencio C, Adam SZ, Nikolaidis P, Yaghmai V, Miller FH. Imaging of the Urachus: Anomalies, Complications, and Mimics. Radiographics. 2016;36:2049-2063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lipskar AM, Glick RD, Rosen NG, Layliev J, Hong AR, Dolgin SE, Soffer SZ. Nonoperative management of symptomatic urachal anomalies. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45: 1016-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Galati V, Donovan B, Ramji F, Campbell J, Kropp BP, Frimberger D. Management of urachal remnants in early childhood. J Urol. 2008;180:1824-6; discussion 1827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zieger B, Sokol B, Rohrschneider WK, Darge K, Tröger J. Sonomorphology and involution of the normal urachus in asymptomatic newborns. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:156-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nogueras-Ocaña M, Rodríguez-Belmonte R, Uberos-Fernández J, Jiménez-Pacheco A, Merino-Salas S, Zuluaga-Gómez A. Urachal anomalies in children: surgical or conservative treatment? J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10:522-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ovington LG. The truth about silver. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004;50:1S-10S. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Bhattacharyya M, Bradley H. A case report of the use of nanocrystalline silver dressing in the management of acute surgical site wound infected with MRSA to prevent cutaneous necrosis following revision surgery. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:45-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bhattacharyya M, Bradley H. Management of a difficult-to-heal chronic wound infected with methycillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in a patient with psoriasis following a complex knee surgery. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2006;5:105-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | King A, Stellar JJ, Blevins A, Shah KN. Dressings and Products in Pediatric Wound Care. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2014;3:324-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Leaper DJ. Silver dressings: their role in wound management. Int Wound J. 2006;3:282-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | August DL, Ireland S, Benton J. Silver-based dressing in an extremely low-birth-weight infant: a case study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2015;42:290-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rustogi R, Mill J, Fraser JF, Kimble RM. The use of Acticoat in neonatal burns. Burns. 2005;31:878-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Dissemond J, Dietlein M, Neßeler I, Funke L, Scheuermann O, Becker E, Thomassin L, Möller U, Bohbot S, Münter KC. Use of a TLC-Ag dressing on 2270 patients with wounds at risk or with signs of local infection: an observational study. J Wound Care. 2020;29:162-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |