Published online Mar 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2616

Peer-review started: October 11, 2021

First decision: November 11, 2021

Revised: December 15, 2021

Accepted: January 5, 2022

Article in press: January 5, 2022

Published online: March 16, 2022

Processing time: 150 Days and 15.6 Hours

With the spread and establishment of the Chest Pain Center in China, adhering to the idea that “time is myocardial cell and time is life”, many hospitals have set up a standardized process that ensures that patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who meet emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) guidelines are sent directly to the DSA room by the prehospital emergency doctor, saving the time spent on queuing, registration, payment, re-examination by the emergency doctor, and obtaining consent for surgery after arriving at the hospital. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is an acute disease that is triggered by intense emotional or physical stress and must be promptly differentiated from AMI for its appropriate management.

A 52-year-old female patient was taken directly to the catheterization room to perform PCI due to 4 h of continuous thoracalgia and elevation of the ST segment in the V3–V5 lead, without being transferred to the emergency department according to the Chest Pain Center model. Loading doses of aspirin, clopidogrel and statins were administered and informed consent for PCI was signed in the ambulance. On first look, the patient looked nervous in the DSA room. Coronary angiography showed no obvious stenosis. Left ventricular angiography showed that the contraction of the left ventricular apex was weakened, and the systolic period was ballooning out, showing a typical “octopus trap” change. The patient was diagnosed with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Five days later, the patient had no symptoms of thoracalgia, and the serological indicators returned to normal. She was discharged with a prescription of medication.

Under the Chest Pain Center model for the treatment of patients with chest pain showing ST segment elevation, despite the urgency of time, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy must be promptly differentiated from AMI for its appropriate management.

Core tip: Under the Chest Pain Center model for the treatment of patients with chest pain with ST segment elevation, despite the urgency of time, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy must be promptly differentiated from myocardial infarction for its appropriate management.

- Citation: Meng LP, Zhang P. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy misdiagnosed as acute myocardial infarction under the Chest Pain Center model: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(8): 2616-2621

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i8/2616.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2616

With the spread and establishment of the Chest Pain Center in China, adhering to the idea that “time is myocardial cells and time is life”, many hospital have set up a standardized process that ensures that acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients who meet emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) guidelines are sent directly to the DSA room by the prehospital emergency doctor, saving the time spent on queuing, registration, payment, re-examination by the emergency doctor, and obtaining consent for surgery after arriving at the hospital. In the emergency ambulance, if the diagnosis of AMI is clear, the prehospital emergency doctor informs the Chest Pain Center to prepare the DSA room, and loading doses of aspirin, clopidogrel and statins are administered to the patient. Meanwhile, informed signed consent for PCI surgery is acquired before arriving at the hospital.

As before, when the patient arrives at the emergency department and is diagnosed with AMI, the cardiologist is invited for consultation. Whether to start the emergency PCI process is decided by the cardiologist according the medical history, patient symptoms, electrocardiogram (ECG), and other laboratory tests; most patients who are taken to the DSA room are patients with AMI. According to the “bypass emergency department” model, which was set up by the Chest Pain Center to save time for patients with AMI, the decision of whether to start the emergency PCI process is made by the prehospital emergency doctor who is not a cardiologist. Sometimes, some diseases similar to AMI are not identified accurately. We have seen some patients during emergency coronary angiography with typical thoracalgia symptoms and ST segment elevation in an ECG, but with no obvious abnormalities. Coronary spasm, thrombotic autolysis, myocarditis, pheochromocytoma, aortic dissection, and other diseases need to be routinely identified[1]. In this case, we report a patient with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy who was misdiagnosed with AMI.

A 52-year-old female patient was taken directly to the catheterization room to undergo PCI due to 4 h of continuous thoracalgia”.

Four hours before admission, the patient experienced sudden right thoracalgia, which could be felt on the back of the sternum and under the xiphoid process. It presented as a dull swelling pain, without shortness of breath or palpitations.

The patient had no documented medical history.

The patient had no documented personal or family history.

The patient looked nervous and no obvious abnormality was found in the patient’s physical examination.

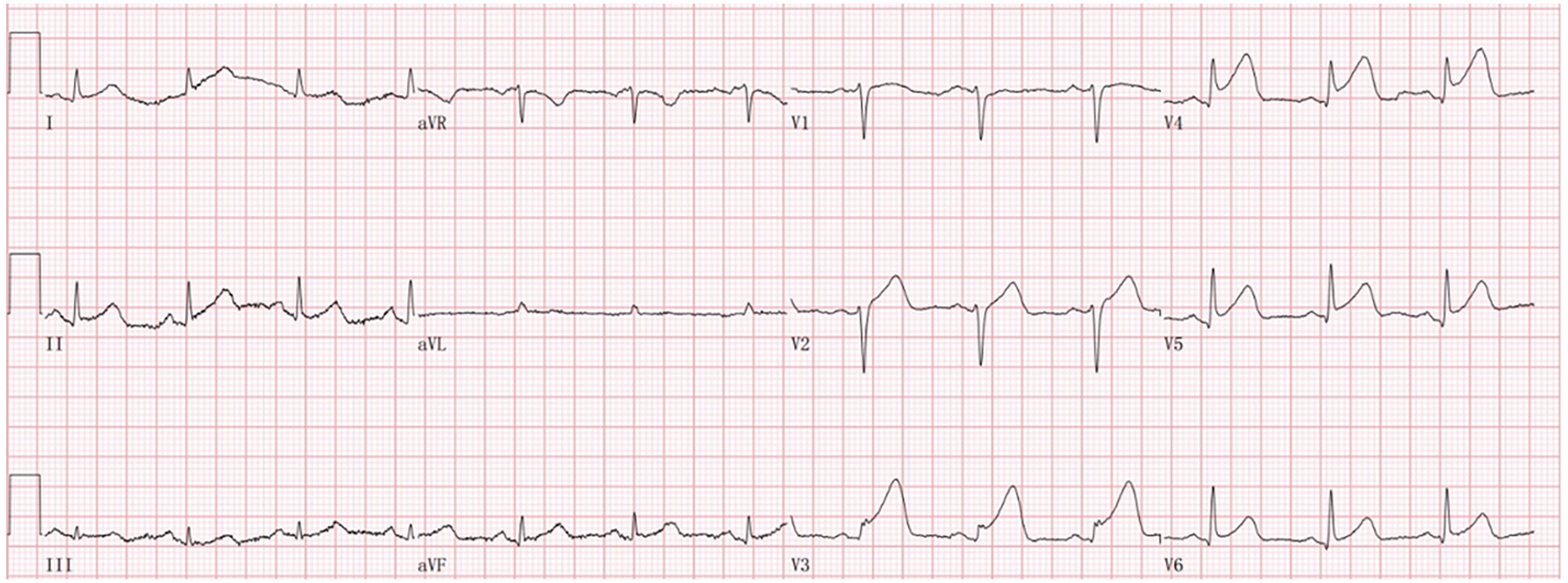

A prehospital ECG showed an upslope elevation of 0.05–0.15 mV in the ST segment of the V3–V5 lead with a towering and upright T wave (Figure 1).

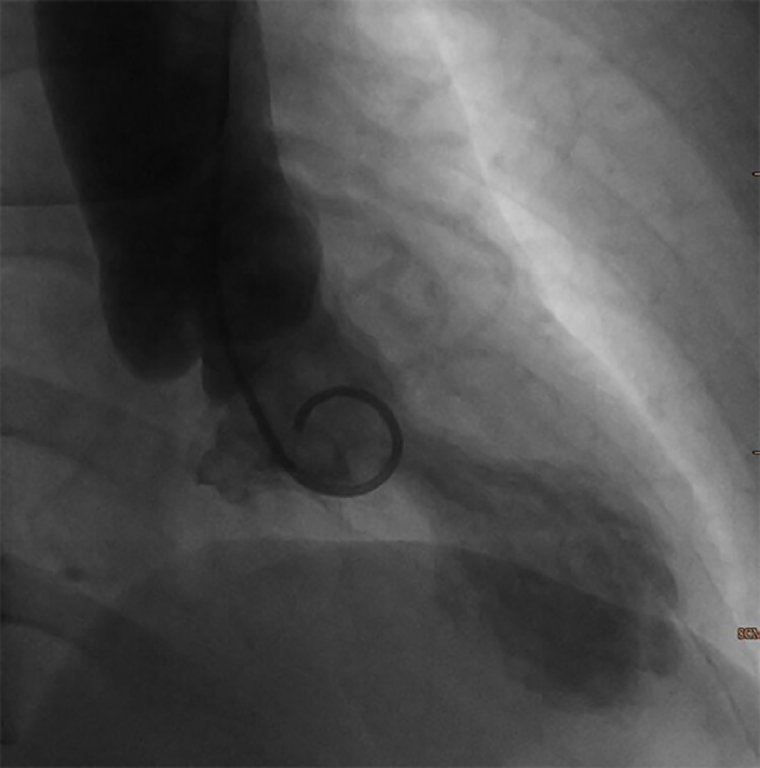

Coronary angiography was performed directly after admission, and no obvious stenosis was observed. Left ventricular angiography showed that the contraction of the left ventricular apex was weakened, and the systolic period was ballooning out, showing a typical “octopus trap” change (Figure 2).

A final diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was made.

According to the ECG combined with the patient’s medical history, the patient was diagnosed with AMI. The Chest Pain Center of our hospital started the detour emergency procedure. In the ambulance, the patient and his family members were informed of the initial diagnosis of AMI, which required PCI, and informed consent for the surgery was signed. Loading doses of aspirin, clopidogrel and statins were administered simultaneously. The patient was taken directly to the DSA room without a visit to the emergency department for further medical examination.

Coronary angiography was performed directly after admission, and no obvious stenosis was observed. Intraoperative troponin was reported at 0.38 mg/mL. During coronary angiography, abnormal heartbeat was noted and the patient was asked for her medical history during the operation. The patient reported that her husband had died unexpectedly 2 d earlier; thus, a broken heart syndrome (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy) was suspected. Left ventricular angiography showed that the contraction of the left ventricular apex was weakened, and the systolic period was ballooning out, showing a typical “octopus trap” change (Figure 2). The results of portable intraoperative ultrasound showed that the myocardial activity in the left ventricular wall was not satisfactory, and there was a small amount of regurgitation in the mitral, tricuspid and aortic valves. No other treatment was administered in the catheter room, and the patient was admitted with the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

After admission, the symptoms of thoracalgia were alleviated, and the patient was put under ECG monitoring and treated with aspirin, clopidogrel (antiplatelet medication), metoprolol to reduce sympathetic tension, isosorbide mononitrate to dilate blood vessels, and candesartan to improve ventricular remodeling. On the day of admission, the patient was administered 25.78 ng/mL troponin, 103.9 U/L creatine kinase isoenzyme, 339.9 U/L lactate dehydrogenase, and 109.2 pg/mL B-type natriuretic peptide. Cardiac ultrasound showed uncoordinated left ventricular wall movement, decreased diastolic function, and decreased ST segment in the V3–V5 lead of the ECG. During the treatment period, the myocardial enzyme spectrum and troponin continued to decline in the patient.

Five days later, the patient had no symptoms of thoracalgia, and the serological indicators returned to normal. She was discharged with a prescription of medication.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also known as broken heart syndrome or acute stress cardiomyopathy, was first described and proposed by Japanese scholar Hikaru Sato and his colleagues in 1990. Eighty percent of cases occur in middle-aged and postmenopausal women and are often induced by sudden mental stimulation or physical stress. Patients have thoracalgia similar to that seen in MI, and ECGs show ST segment elevation, T-wave inversion, and release of a spectrum of myocardial enzymes[2-4]. Since the central chamber on a ventriculogram is similar in shape to a Japanese octopus trap (Figure 2), this is also referred to as octopus trap cardiomyopathy. The Mayo Clinic in 2007 defined the disease as having the following symptoms: (1) Transient hypokinesis, akinesis, or dyskinesis of the left ventricular mid segments with or without apical involvement with regional wall motion abnormalities extending beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution; a stressful trigger is often, but not always present; (2) Absence of obstructive coronary disease or angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture; (3) New electrocardiographic abnormalities (either ST segment elevation and/or T-wave inversion) or modest elevation in cardiac troponin; and (4) Absence of pheochromocytoma myocarditis[5]. Different from AMI, in which the blocked blood vessels need to be reopened as soon as possible, the primary treatment for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is to remove the factor causing psychological stress and regulate the mental state of the patient and relax their mood. The intense preoperative conversation regarding PCI and the urgent operation process for AMI according to the Chest Pain Center model can aggravate a patient’s psychological condition, increasing the release of cardiac neuronal and systemic catecholamines, finally leading to aggravation of the progression of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy[6]. Therefore, the differential diagnosis of AMI and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is particularly important for the prehospital emergency doctor.

Sent directly to the DSA room from the ambulance, the patient did not undergo an ECG; therefore, incongruity of left ventricular wall movement was difficult to detect. As she was also not asked about her medical history in detail, the cardiologist was unaware that she had experienced recent psychological stress. The emergency coronary angiography showed no obvious abnormality, and the surgeon first considered a diagnosis of thrombus autolysis, but noticed an abnormal heartbeat during the operation. Combined with the fact that the patient was a middle-aged woman, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was suspected. After asking the patient about her medical history during the operation, the surgeon learned that the patient had suffered a major psychological blow due to the unexpected death of her husband 2 d earlier. The patient underwent left ventricular angiography, in which the surgeon found that the contraction of the left ventricular apex was weakened and the systolic period was bulbous, showing typical octopus trap changes (Figure 2). The results of the portable intraoperative ultrasound showed that the myocardial activity of the left ventricular wall was uncoordinated. The patient’s history and the above examination results met the diagnostic criteria for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy proposed by the Mayo Clinic.

With the establishment of the Chest Pain Center and improvement of the detour emergency procedures for patients with acute coronary syndrome, we have seen many patients during emergency coronary angiography with typical thoracalgia symptoms and ST segment elevation in ECGs, but with no obvious abnormalities. Coronary spasm, thrombotic autolysis, myocarditis, pheochromocytoma, aortic dissection, and other diseases have been routinely identified[1]. In this case, cardiac imaging abnormalities were observed intraoperatively, and left ventricular angiography was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Patients who detour the emergency department according to the Chest Pain Center procedures do not undergo complete preoperative preparation and do not receive routine evaluation tests such as chest X-rays and echocardiograms. Consent for PCI was obtained from the patient and her family members in the ambulance in transit. The surgeon was unaware of the patient’s history of acute psychological stress and did not consider a diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Dana et al looked at cases over the last decade and found that Takotsubo cardiomyopathy accounted for about 7% of patients initially diagnosed with MI. The number of patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was far less in our previous clinical work and has been reported to increase in recent years as more cardiologists recognize the condition[7-9]. For patients with normal emergency coronary angiography, this disease should be considered in the routine differential diagnosis. The accuracy of diagnosis can be improved by asking about the medical history prior to operation and performing portable cardiac ultrasound on the surgical platform.

Under the Chest Pain Center model for treatment of patients with chest pain showing ST segment elevation, despite the urgency of time, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy must be promptly differentiated from AMI for its appropriate management.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oley MH, Ullah K S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Pelliccia F, Kaski JC, Crea F and Camici PG. Pathophysiology of takotsubo syndrome. Circulation. 2017;135:2426-2441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 58.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dawson DK. Acute stress-induced (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2018;104:96-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kato K, Lyon AR, Ghadri J-R and Templin C. Takotsubo syndrome: aetiology, presentation and treatment. Heart. 2017;103:1461-1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Y-Hassan S and Tornvall P. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management of takotsubo syndrome. Clin Auton Res. 2018;28:53-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Prasad A, Lerman A and Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008;155:408-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1193] [Cited by in RCA: 1297] [Article Influence: 76.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lyon AR, Citro R, Schneider B, Morel O, Ghadri JR, Templin C, Omerovic E. Pathophysiology of takotsubo syndrome: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:902-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 47.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bertin N, Brosolo G, Antonini-Canterin F, et al: Takotsubo syndrome in young fertile women. Acta Cardiol: 1-9, 2019.. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kalra DK, Lichtenstein SJ, Bai C, et al: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a man with no trigger and multiple cardioembolic complications-A rare constellation. Echocardiography 36: 975-979, 2019.. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Muratsu A, Muroya T and Kuwagata Y: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the intensive care unit. Acute Med Surg 6: 152-157, 2019.. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |