Published online Mar 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2610

Peer-review started: October 17, 2021

First decision: December 3, 2021

Revised: December 26, 2021

Accepted: February 10, 2022

Article in press: February 10, 2022

Published online: March 16, 2022

Processing time: 144 Days and 7.3 Hours

Systemic emphysematous infection caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumo

We report a rare case of systemic emphysematous infection via hematogenous dissemination from a liver abscess caused by K. pneumoniae, complicated by multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, septic shock, bacteremia, emphysematous cystitis, prostate and left seminal vesicle abscesses in a diabetic patient. The patient simultaneously presented with spontaneous pneumoperitoneum secon

Early diagnosis followed by efficient antibiotic therapy and surgical management are essential for systemic emphysematous infection.

Core Tip: Systemic emphysematous infection caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae is a rare but lethal infection. The combination of emphysematous liver abscess, emphysematous cystitis, prostate and left seminal vesicle abscesses, bacteremia, septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome are even rarer. The patient simultaneously presented with spontaneous pneumoperitoneum secondary to rupture of the emphysematous liver abscess, which is an extremely rare clinical condition inducing intra-abdominal sepsis that further increases the mortality rate.

- Citation: Zhang JQ, He CC, Yuan B, Liu R, Qi YJ, Wang ZX, He XN, Li YM. Fatal systemic emphysematous infection caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(8): 2610-2615

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i8/2610.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2610

Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) is a Gram-negative pathogenic bacterium belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family, usually causes various infections including pneumonia, urinary tract infections, hepatobiliary infections and intra-abdominal infections[1]. K. pneumoniae strains are divided into the classical group and hypervirulent group. Classical K. pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen and primarily infects critically ill and immunocompromised patients, and causes health-care associated infections; the hypervirulent pathotype usually infects healthy individuals and causes community-acquired infections[2-3]. In recent years, several studies have reported a distinctive clinical syndrome, invasive K. pneumoniae liver abscess syndrome (IKLAS), which typically occurs in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and is characterized by a liver abscess, bacteremia, and hematogenous extrahepatic infection at sites such as the eye, brain, or lung. We report a rare case of IKLAS presenting with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), septic shock, bacteremia, numerous emphysematous liver abscesses, pneumoperitoneum, emphysematous cystitis, prostate and left seminal vesicle abscesses in a diabetic patient whose infection progressed rapidly and died within a short period.

A 66-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with a 14-d history of worsening fatigue, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, and a 3-d history of confusion and jaundice.

Fourteen days prior to hospital admission, he suffered from fatigue, anorexia, nausea and vomiting. The patient did not visit his doctor, the symptoms of nausea and vomiting gradually improved but fatigue and anorexia persisted. His family members found that he had been showing signs of confusion and jaundice 3 d earlier. He vomited 50 mL of coffee-colored gastric contents one day earlier. He had no fever, abdominal pain and lower urinary tract symptoms.

His past medical history included acute gastric ulcer perforation which was repaired 40 years earlier, hypertension treated with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide, type 2 DM without regular control treated with metformin, acarbose and insulin for 10 years, chronic prostatitis and chronic diarrhea for the past 10 years, and a cerebral infarction 8 years and 3 mo previously. He had acute calculous cholecystitis with hypotension 2 mo ago and received empirical antibiotics with ceftazidime 2.0 g and ornidazole 0.5 g intravenous route every 12 h for 10 days, blood and bile cultures and cholecystectomy were not performed.

No relevant family history, travelling history or animal contact was reported.

His initial vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 70/50 mmHg, pulse 110 bpm, respiratory rate 30 breaths/min, and body temperature of 36.5 °C. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score was 23, and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was 13. He demonstrated confusion, icteric sclera, normal cardiopulmonary auscultation, a soft, non-tender abdomen, and acrocyanosis with scattered marble patches on wet and cold lower limbs.

Markedly raised inflammatory parameters were found including the following: white blood cell count 18.8 × 109/L (93% neutrophils and 1% lymphocytes), C-reactive protein 315 mg/L, interleukin 6 > 5000 pg/mL, and procalcitonin (PCT) 70 ng/mL. Serum biochemical tests showed total bilirubin 210.9 μmol/L, direct bilirubin 165.7 μmol/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 940 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 3870 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 1429 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 7852 U/L, blood urea nitrogen 48.1 mmol/L and creatinine 339.3 μmol/L. The level of blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was 10.25 mmol/L and 8.4% respectively. A coagulation panel demonstrated a prothrombin time (PT) of 21.3 s, prothrombin time activity (PTA) 39%, international normalized ratio (INR) 1.9, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) 38.7 s and D-dimer 7.25 μg/mL. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.273, undetectable PCO2 (A fall in PCO2 was beyond the range of the Point-of-Care Testing device), PO2 90.2 mmHg and lactate 20 mmol/L. In addition, routine urine analysis revealed numerous red blood cells (50-60/high power field), white blood cells (35-40/high power field), bilirubin and albuminuria. The patient was not anemic (blood Hb 133 g/L) and hematocrit was 39.7%. Serology showed that human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, hepatitis B and C were all negative.

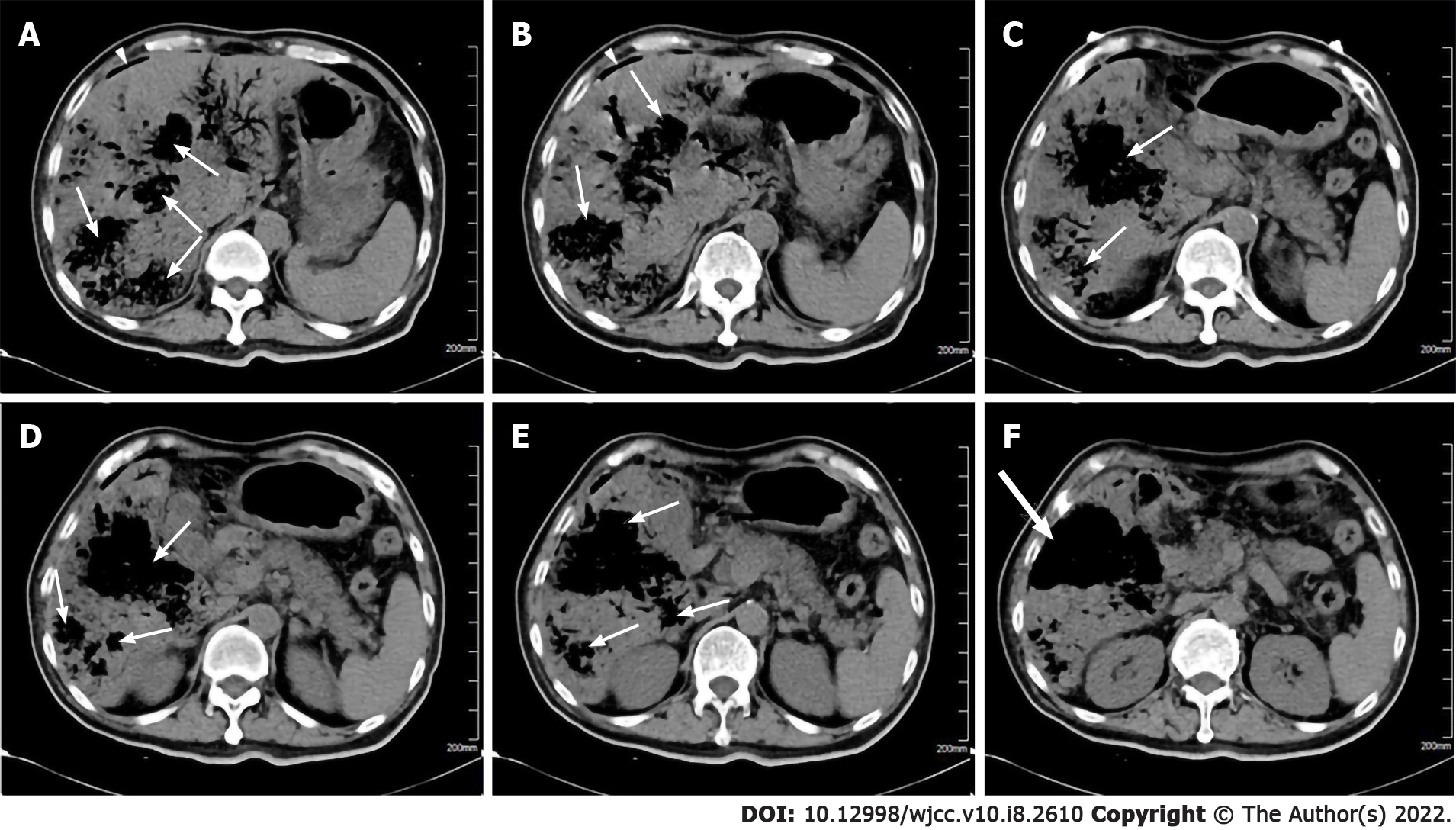

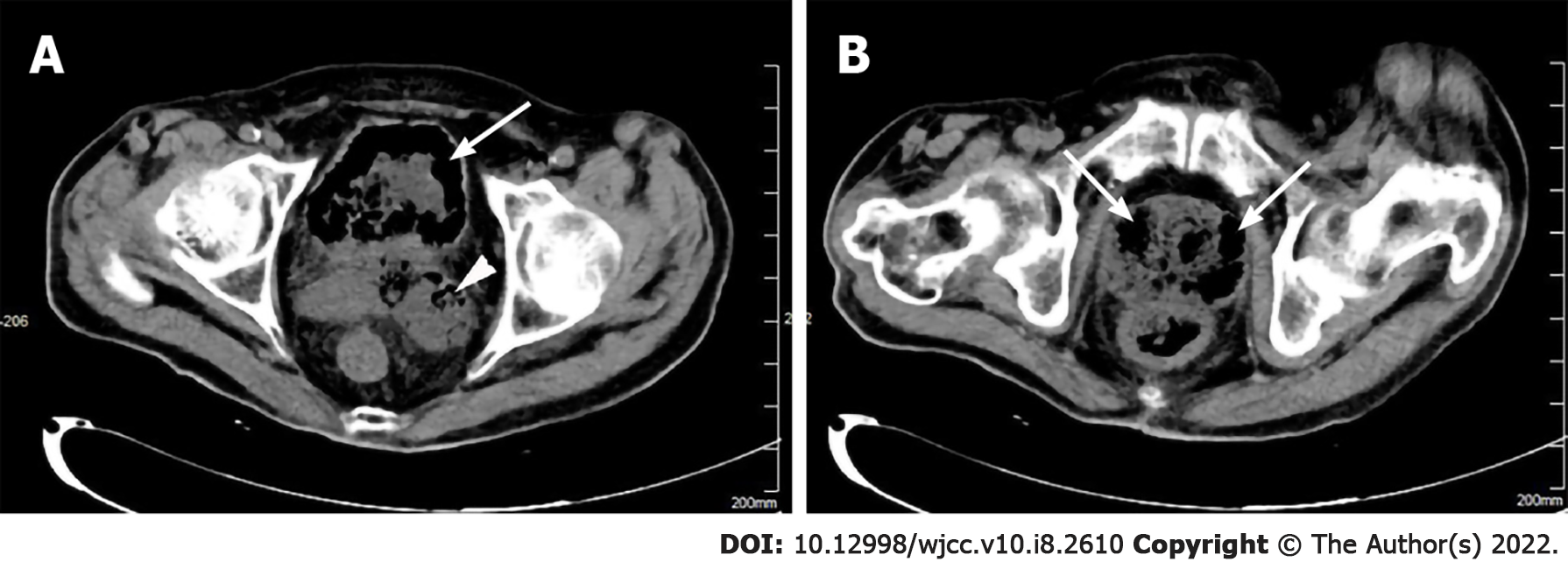

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan displayed numerous emphysematous hepatic abscesses, rupture of some liver abscesses and gas formation in the right subphrenic area (Figure 1). Pelvic CT showed intramural gas formation in the bladder and an enlarged prostate and left seminal vesicle with abnormal air accumulation (Figure 2). Chest CT revealed pulmonary infiltrates in the right lower lobes and small right pleural effusions.

The clinical diagnosis was IKLAS with septic shock and MODS accompanied by emphysematous prostate and left seminal vesicle abscesses and cystitis.

Empiric antimicrobial treatment with meropenem was administered along with fluid resuscitation and vasoactive support with noradrenaline. Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration was then initiated for acute kidney injury and persistent inflammatory state after adequate fluid resuscitation. A consultant hepatobiliary surgeon suggested an emergency surgical exploration but this was refused by his family. We attempted percutaneous liver abscess drainage guided by bedside ultrasound, but did not succeed due to liver abscess cavities totally occupied by air and pneumoperitoneum. His condition rapidly deteriorated, he developed emerging thrombocytopenia, decreased Hb, a progressive increase in serum enzyme levels in addition to severe metabolic acidosis, persistent renal failure and liver dysfunction, and subsequently developed respiratory failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation and coma. At that time, his laboratory examinations showed lactate 30 mmol/L, pH 7.193, HCO3− 11.6 mmol/L, base excess −18.4 mmol/L, SO2 89.6%, PO2/FiO2 159, platelets 28×109/L, Hb 86 g/L, INR 3.37, PT 39 s, PTA 21%, APTT 57.7 s, D-dimer 7.25 μg/mL, ALT 1501 U/L, AST 6012 U/L, CK 1700 U/L and LDH 12356 U/L. The patient was immediately intubated and mechanical ventilation was initiated. Despite these aggressive treatments, the patient’s condition was critical and exacerbated, with persistent MODS and hemodynamic instability despite large doses of noradrenaline (2.5 μg/kg/min).

Twenty-two hours after admission, the patient died. Two days later, cultures from peripheral blood and urine specimens revealed K. pneumoniae with a positive string test, but antimicrobial susceptibility testing was not carried out.

The first case series of IKLAS was described in Taiwan in 1986[4] and it subsequently emerged as a global infectious disease although the majority of cases were found in southeast Asia. Our patient had a rare clinical condition with a poor prognosis and had distinctive clinical features such as ruptured emphysematous liver abscesses with concomitant pneumoperitoneum, emphysematous prostate and left seminal vesicle abscesses and emphysematous cystitis. The patient was in a critical condition complicated by MODS (kidney, liver, circulation, respiratory, coagulation) and rapidly deteriorated following admission. The fatal infection was caused by a strain of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae identified by a positive string test, which was more virulent than classical K. pneumoniae and capable of causing multiple sites of infection due to hematogenous spread[3].

The etiology of IKLAS is unknown. Our patient suffered from chronic diarrhea without abdominal pain and fever which may be noninfectious and functional diarrhea and is not considered the etiologic factor for IKLAS, even though gastrointestinal colonization is a major reservoir for K. pneumoniae-induced infections[5]. He had acute calculous cholecystitis with hypotension 2 mo ago and received empirical antibiotics for 10 d without blood and bile cultures and cholecystectomy. Therefore, we speculated that the liver abscesses were attributable to the cholecystitis with inadequately management that led bacteria to invade the liver parenchyma via the gallbladder bed. In addition, several studies have shown that DM is a significant risk factor for IKLAS[6] and poor glycemic control tends to increase the rate of disseminated infection[7]. Our patient had DM for 30 years and his HbA1c was 8.4% on admission, the immunosuppression related to DM may predispose patients to the development of IKLAS.

Emphysematous liver abscess is a rare but life-threatening infection which is characterized by hepatic parenchymal emphysematous change. In rare circumstances, emphysematous liver abscesses are prone to spontaneous rupture resulting in secondary peritonitis and intra-abdominal sepsis which can further increase mortality rate[8]. Our patient presented with pneumoperitoneum secondary to spontaneous rupture of emphysematous liver abscesses, with no evidence of hollow viscus perforation. Multiple emphysematous liver abscesses that spread throughout the liver resulted in severely destructive hepatic tissue, and extensive gas formation in the abscess was vulnerable to spontaneous rupture as gas increases the tension within the abscess cavity. Gas in the abscess is believed to be due to the fermentation of glucose into carbon dioxide by K. pneumoniae under anaerobic conditions[9-10]. In patients with numerous abscesses, it is difficult to locate and drain all the lesions via percutaneous, laparoscopic or surgical intervention, thus the mortality rate is reported to be extremely high at 27%-30%[9]. Control of the infectious source is very important, failure to timely surgery or percutaneous drainage is our limitation and the lessons should be learned.

The multifocal emphysematous infections in our patient consisting of liver abscesses, cystitis, prostate and seminal vesicle abscesses are extremely rare. Emphysematous cystitis is characterized by the presence of gas in and around the bladder wall and can be treated successfully with bladder drainage and antibiotics[11]. Emphysematous prostate abscess is not often diagnosed at an early stage due to non-specific symptoms and may be confirmed by CT which shows gas and abscess accumulation in the prostate[12]. Surgical drainage of a prostate abscess can be performed by the transrectal, transperineal or transurethral approach[13]. It is recommended in critically ill patients, such as our case, that CT-guided transperineal drainage of an emphysematous prostate abscess should be performed[14].

K. pneumoniae is the common pathogen associated with emphysematous infections. Among the members of the K. pneumoniae complex which consists of seven K. pneumoniae-related species, K. variicola is frequently misidentified as K. pneumoniae by routine clinical microbiology diagnostics in most modern laboratories[15]. More recently, K. variicola is recognized as a cause of emphysematous infections[16] with a higher mortality rate when compared to K. pneumoniae[17]. Thus, clinicians should be aware of the potential of K. variicola involvement as emphysematous infections and identify K. variicola among K. pneumoniae infections based on mass spectrometry and genome sequencing[18-19].

IKLAS is a rare but severe infection which can be lethal if the diagnosis is delayed and can progress to septic shock and MODS. Spontaneous pneumoperitoneum secondary to ruptured emphysematous liver abscesses can induce intra-abdominal sepsis that further increases the mortality rate. Early diagnosis followed by efficient antibiotic therapy and surgical management are essential for these life-threatening infections.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Moldovan C, Shelat VG S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:881-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 600] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Martin RM, Bachman MA. Colonization, Infection, and the Accessory Genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 504] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Article Influence: 82.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Russo TA, Marr CM. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 705] [Article Influence: 117.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu YC, Cheng DL, Lin CL. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess associated with septic endophthalmitis. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:1913-1916. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gorrie CL, Mirceta M, Wick RR, Edwards DJ, Thomson NR, Strugnell RA, Pratt NF, Garlick JS, Watson KM, Pilcher DV, McGloughlin SA, Spelman DW, Jenney AWJ, Holt KE. Gastrointestinal Carriage Is a Major Reservoir of Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection in Intensive Care Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:208-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim JK, Chung DR, Wie SH, Yoo JH, Park SW; Korean Study Group for Liver Abscess. Risk factor analysis of invasive liver abscess caused by the K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lin YT, Wang FD, Wu PF, Fung CP. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in diabetic patients: association of glycemic control with the clinical characteristics. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pham Van T, Vu Ngoc S, Nguyen Hoang NA, Hoang Huu D, Dinh Duong TA. Ruptured liver abscess presenting as pneumoperitoneum caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae: a case report. BMC Surg. 2020;20:228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Takano Y, Hayashi M, Niiya F, Nakanishi T, Hanamura S, Asonuma K, Yamamura E, Gomi K, Kuroki Y, Maruoka N, Inoue K, Nagahama M. Life-threatening emphysematous liver abscess associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tan EY, Lee CW, Look Chee Meng M. Spontaneous pneumoperitoneum resulting from the rupture of a gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:251-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mokabberi R, Ravakhah K. Emphysematous urinary tract infections: diagnosis, treatment and survival (case review series). Am J Med Sci. 2007;333:111-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li Z, Wen J, Zhang N. Emphysematous prostatic abscess due to candidiasis: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e19391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tai HC. Emphysematous prostatic abscess: a case report and review of literature. J Infect. 2007;54:e51-e54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bae GB, Kim SW, Shin BC, Oh JT, Do BH, Park JH, Lee JM, Kim NS. Emphysematous prostatic abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae: report of a case and review of the literature. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:758-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rodríguez-Medina N, Barrios-Camacho H, Duran-Bedolla J, Garza-Ramos U. Klebsiella variicola: an emerging pathogen in humans. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8:973-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jie TTZ, Shelat VG. Emphysematous Cholecystitis: A Phytotic Disease from an Emerging Pathogen, Klebsiella variicola. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2021;22:875-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Maatallah M, Vading M, Kabir MH, Bakhrouf A, Kalin M, Nauclér P, Brisse S, Giske CG. Klebsiella variicola is a frequent cause of bloodstream infection in the stockholm area, and associated with higher mortality compared to K. pneumoniae. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rodrigues C, Passet V, Rakotondrasoa A, Brisse S. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella quasipneumoniae, Klebsiella variicola and Related Phylogroups by MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:3000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Long SW, Linson SE, Ojeda Saavedra M, Cantu C, Davis JJ, Brettin T, Olsen RJ. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Human Clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates Reveals Misidentification and Misunderstandings of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella variicola, and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae. mSphere. 2017;2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |