Published online Mar 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2550

Peer-review started: August 31, 2021

First decision: November 17, 2021

Revised: November 18, 2021

Accepted: January 27, 2022

Article in press: January 27, 2022

Published online: March 16, 2022

Processing time: 191 Days and 9.8 Hours

Vancomycin remains a first-line treatment drug as per the treatment guidelines for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia. However, a number of gram-positive cocci have developed resistance to several drugs, including glycopeptides. Therefore, there is an urgent need for effective and innovative antibacterial drugs to treat patients with infections caused by drug-resistant bacteria.

A 24-year-old male was admitted to hospital owing to lumbago, fever, and hematuria. Computed tomography (CT) results showed an abscess in the psoas major muscle of the patient. Repeated abscess drainage and blood culture suggested MRSA, and vancomycin was initiated. However, after day 10, CT scans showed abscesses in the lungs and legs of the patient. Therefore, treatment was switched to daptomycin. Linezolid was also added considering inflammation in the lungs. After 10 d of the dual-drug anti-MRSA treatment, culture of the abscess drainage turned negative for MRSA. On day 28, the patient was discharged without any complications.

This case indicates that daptomycin combined with linezolid is an effective remedy for bacteremia caused by MRSA with pulmonary complications.

Core Tip: We analyzed a case of severe methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia who failed to respond to first line treatment using vancomycin. We believe that our study makes a significant contribution to the literature because it indicates that daptomycin combined with linezolid is an effective remedy for bacteremia caused by MRSA with pulmonary complications.

- Citation: Hong XB, Yu ZL, Fu HB, Cai ZH, Chen J. Daptomycin and linezolid for severe methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus psoas abscess and bacteremia: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(8): 2550-2558

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i8/2550.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i8.2550

Vancomycin is the first-line treatment drug as per the treatment guidelines for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. However, daptomycin is considered to be at least as effective as vancomycin in treating MRSA bacteremia, and a high dose of daptomycin is recommended in combination with another drug (including gentamicin, rifampicin, or linezolid) as a salvage treatment plan for persistent MRSA bacteremia when vancomycin fails. In general, the basic principles of using combination therapy involve a wide antibacterial spectrum, synergistic effect, and low risk of development of drug-resistant strains[1]. Daptomycin is a cyclic lipopeptide antibacterial agent produced by Streptomyces roseosporus. This agent targets the bacterial cell membrane through calcium-dependent pathways, disrupting electrical potential, altering cell membrane permeability, opening ion channels, and eventually causing cell death[2]. The drug has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for adult patients with MRSA infections, including MRSA blood flow infections, right-sided infective endocarditis, and complicated skin and soft tissue infections[3]. Several studies have shown that daptomycin exhibits very good efficacy against bacteremia caused by MRSA, even when the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of vancomycin is high[4]. In general, the use of 6 mg/kg daptomycin is recommended each day for bacteremia caused by MRSA[2]. However, several studies have shown that up to 8 mg/kg daptomycin each day is required for patients with refractory MRSA infections[5,6]. In such clinical situations, the combination of daptomycin and other synergistic antibacterial agents may serve as an effective therapeutic strategy. In this report, a case of severe MRSA bacteremia observed in the clinical setting was analyzed to provide a reference for clinical treatment.

The patient (male, aged 24 years, height 175 cm, weight 72 kg, Han nationality, unmarried) was admitted to our hospital for bilateral lumbago without obvious inducement and fever accompanied by hematuria for 14 d. He complained of reduced urine volume and gross hematuria at the end of urination.

He visited another hospital, but experienced not significant pain relief, before visiting our hospital for treatment.

The patient did not have any past medical history.

The patient did not have any personal and family history.

The highest body temperature was recorded to be 37.7 °C.

Laboratory examination results upon admission were the following: white blood cell (WBC), 42.08 × 109/L; neutrophil count (NEUT %), 0.89; C-reactive protein (CRP), 271.42 mg/L; procalcitonin (PCT), 46.97 ng/mL; creatinine, 199 μmol/L; Na, 123 mmol/L; alanine aminotransferase, 63 U/L; aspartate transaminase, 96 U/L; and total bilirubin, 177.3 μmol/L. Abscess drainage culture was positive, but blood culture was negative for MRSA [Sensitive to vancomycin (MIC 0.5 μg/mL), teicoplanin, linezolid, and daptomycin; Table 1].

| Antibiotics | MIC (mg/mL) | MIC categories | ||

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | |

| Penicillin G | ≥ 0.5 | ≥ 0.5 | R | R |

| Oxacillin | ≥ 4 | ≥ 4 | R | R |

| Gentamicin | ≤ 0.5 | ≤ 0.5 | S | S |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5 | 0.5 | S | S |

| Erythromycin | ≥ 8 | ≥ 8 | R | R |

| Clindamycin | ≥ 4 | ≥ 4 | R | R |

| Linezolid | 2 | 2 | S | S |

| Teicoplanin | ≤ 0.5 | ≤ 0.5 | S | S |

| Vancomycin | ≤ 0.5 | 1 | S | S |

| Tigecycline | ≤ 0.12 | ≤ 0.12 | S | S |

The chest, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans revealed the following: multiple lesions in the left psoas major, iliopsoas, iliacus, and piriformis, suggesting the possibility of inflammation and abscess formation accompanied by a small amount of local pneumatosis; multiple calculi in the left kidney; a calculus in the left upper ureter; and mild dilation and effusion in the left renal pelvis, calyx, and upper ureter.

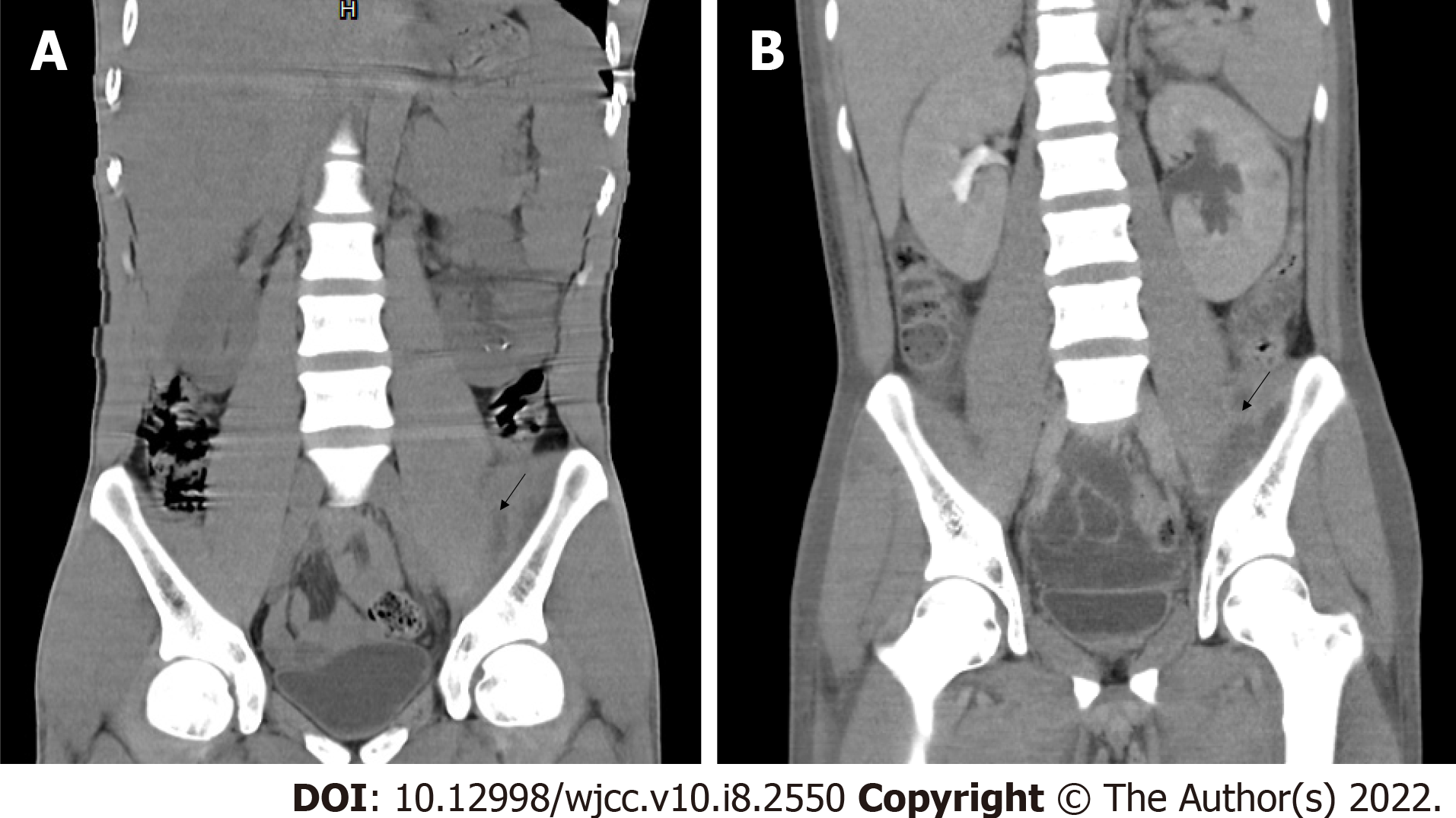

He was admitted to the emergency department (observation area) of our hospital on May 27, 2020, where treatment with vancomycin (1 g every 12 h) was initiated. His condition did not significantly improve after active anti-infective treatment (vancomycin 1 g every 12 h), percutaneous catheter drainage from the psoas major and gluteus maximus, and other treatments. CT re-examination on June 2, 2020 showed that the abscess in the psoas major was similar to that reported in the previous scan (Figure 1). Bilateral pleural effusion had further progressed. Re-examination on June 3, 2020 revealed the following: WBC, 23.59 × 109/L; NEUT %, 0.902; CRP, 113.2 mg/L; creatinine, 176 μmol/L; Na, 126 mmol/L; PCT, 2.57 ng/mL. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) on June 3, 2020.

Conditions upon transfer to the ICU on 3 June 2020 were as follows: fever, temperature of 37.9 °C; shortness of breath, respiratory rate 33 bpm; stable circulation; and fast heart rate, 116 bpm. As the patient had multiple renal calculi accompanied by ureteral calculi, indwelling urinary catheter, and a complicated urinary tract infection, common pathogenic bacteria of urinary tract infections, including Enterobacteriaceae bacteria such as Escherichia coli, were assumed to be present. Thus, imipenem and cilastatin sodium (1 g every 8 h) was added to the treatment regimen to treat the urinary tract infection upon transfer to the ICU. The dose of vancomycin was maintained, and blood was drawn to measure the trough concentration.

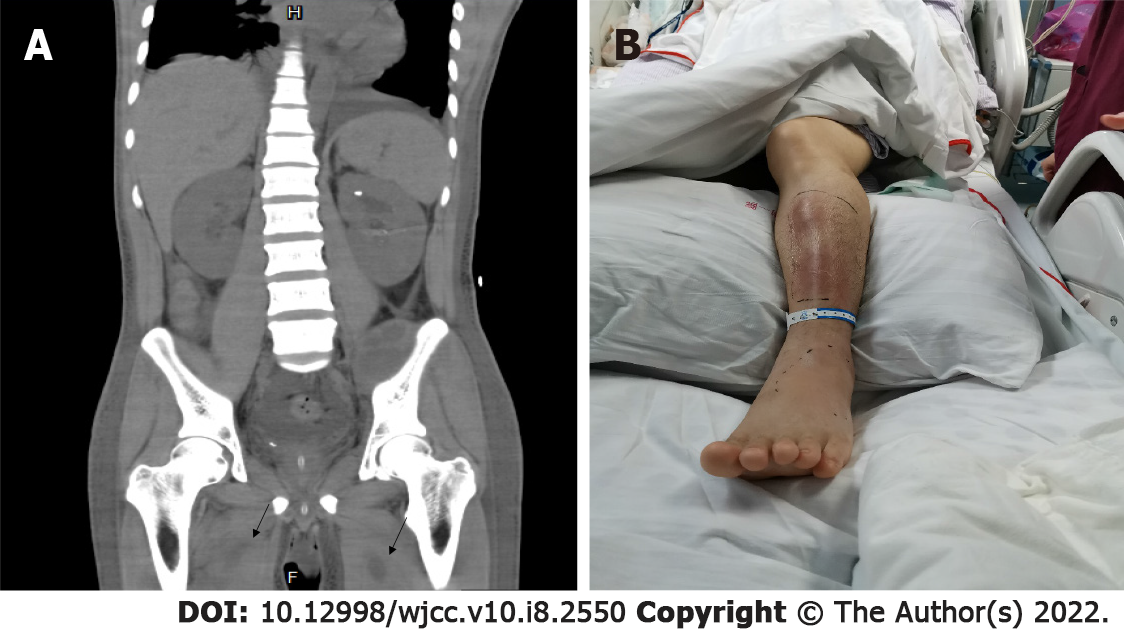

Pathogenic metagenomics testing on June 4, 2020 revealed Streptomyces aureus presence both in the blood and the right gluteus maximus drainage fluid. Culture of the drained pus continued to show presence of MRSA [sensitive to vancomycin (MIC 1.5 μg/mL, an increase from that of earlier), teicoplanin, linezolid, and daptomycin]. The patient had persistent hyperpyrexia on June 5, 2020, with the highest temperature of 38.9 °C (the duration with a temperature above 38 °C was 13 h). The anterior side of the left leg was red and swollen. Flowing liquid was observed under B-ultrasonography, indicating a new abscess. CT scans of the thighs and lungs also revealed new infectious lesions (Figure 2). The decreases in inflammation indicators were not significant (CRP, 139.62 mg/L; WBC, 26.86 × 109/L; NEUT %, 0.883).

Psoas abscess, sepsis (MRSA bacteremia), kidney calculi with ureteral calculi, skin and soft tissue infection.

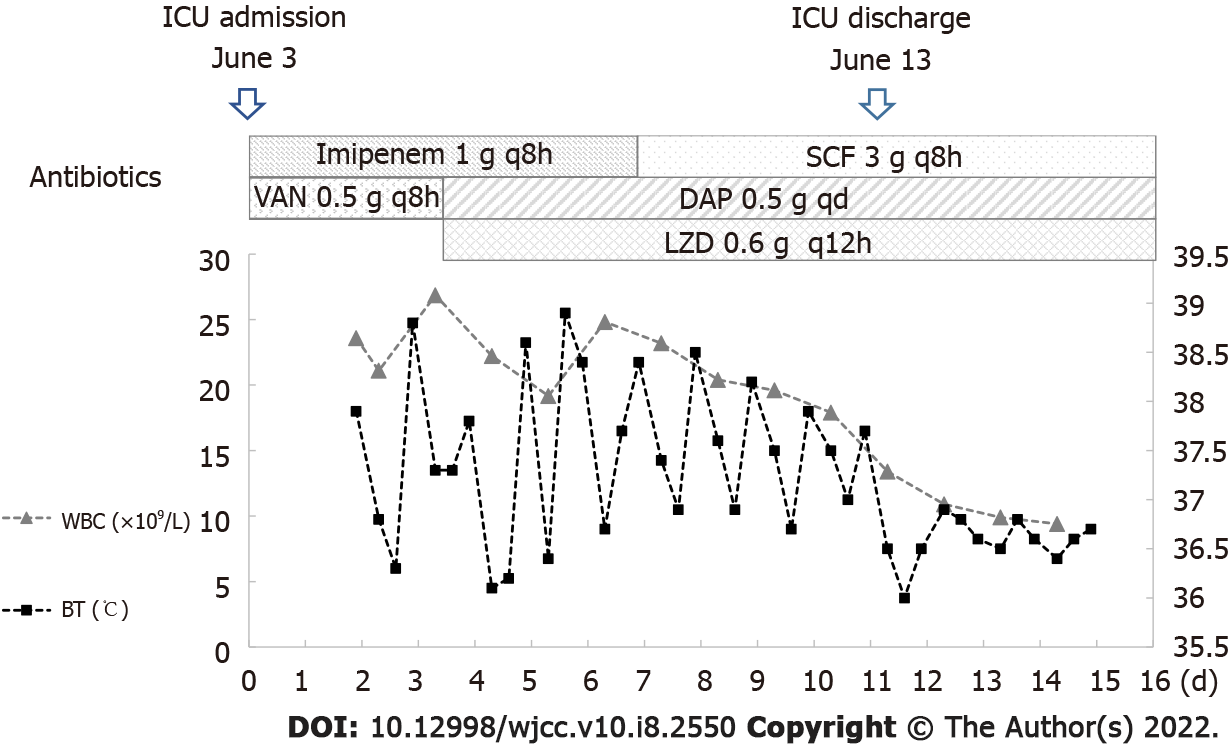

The trough concentration of vancomycin was 35.18 μg/mL. Although the trough concentration of vancomycin reached the target, infection control was poor. Following these results, the patient was switched from vancomycin to daptomycin (0.5 g daily). At the same time, slight high-density patchy shadows were found in the lower lobes of both lungs; thus, the spread of the infection to the lungs through blood circulation could not be ruled out. Therefore, linezolid was added to treat the possible MRSA infection in the lungs (Figure 3).

The patient also had a ureteral obstruction, and ultrasound-guided catheter drainage from the left renal pelvis performed on June 5, 2020. On June 6, 2020, fever persisted, but the peak temperature was lower than that observed earlier, with the highest temperature of 38.8 °C (the duration with a temperature above 38 °C was 10 h). The duration of fever was shorter and the values of infection indicators were lower (CRP, 79.86 mg/L; WBC, 19.17 × 10 9/L; NEUT %, 0.841; PCT, 0.61 ng/mL) than those earlier. On June 13, 2020, the patient had stable respiration and circulation, shorter fever duration (the duration with a temperature above 38 °C was 8 h), and decreased levels of infection indicators than those earlier, suggesting that the infection was controlled. Therefore, the patient was transferred back to the general ward for further treatment.

After the transfer to the general ward, the combination of daptomycin (0.5 g daily, June 5–June 23) and linezolid (0.6 g every 12 h, June 5–July 3) was continued to be administered as anti-infection treatment, while imipenem and cilastatin sodium were de-escalated to cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium to combat gram-negative bacteria infection (Figure 3). On June 15, 2020, the culture of the patient drainage was tested negative and no fever was reported. On June 29, 2020, the levels of PCT, WBC, CRP, and NEUT % were 0.21 ng/mL, 10.36 × 109/L, 35.56 mg/L, and 0.706, respectively, and no fever was recorded. On July 3, 2020, the patient was in stable condition without fever. Considering the left nephrostomy of the patient and the amelioration of urinary obstruction, the department of urology suggested to maintain the left nephrostomy tube unobstructed, which could be treated after the complete recovery of the patient. Therefore, the patient was discharged on July 3, 2020.

According to the 2014 Infectious Diseases Society of America Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections (SSTIs)[7], the infection of the patient belonged to the category of severe purulent SSTIs, which was treated by incision and drainage of a small volume of fluid. During hospitalization, multiple drainage fluid cultures and next-generation sequencing (blood and drainage fluid samples) indicated MRSA (sensitive to vancomycin MIC 0.5 μg/mL) infection, consistent with the fact that Streptomyces aureus is a common pathogen of skin and soft tissue infections. The patient was administered vancomycin (1 g every 12 h) after admission. The levels of infection indicators decreased, but high fever persisted. CT re-examination showed that the abscess was similar to that observed before. As the creatinine level was 176 μmol/L and creatinine clearance rate was 56.4 mL/min, the condition was mild renal insufficiency; hence, it was not necessary to reduce the vancomycin dose of 0.5 g every 8 h (loading dose 1 g). Although the trough concentration of vancomycin on June 5, 2020 was 35.18 μg/mL, the infection continued to spread further from the original site in the psoas major to the thighs, legs, and lungs.

There might have been two reasons for the spread of the infection. First, the MIC value of vancomycin increased; the initial MIC value was 0.5 μg/mL, which increased to 1.5 μg/mL on June 5, 2020, suggesting that the sensitivity to vancomycin decreased. For a long time, vancomycin has been used as the gold standard for the treatment of MRSA infections, but there have been clinical reports on strains with MIC values of 1–2 μg/mL where the underlying infections were associated with treatment failure[8]. According to the latest guidelines on vancomycin in 2020[9], both in vitro and in vivo experiments of vancomycin have shown that the ratio of 24 h area under the concentration-time curve to MIC (AUC/MIC) can effectively predict the efficacy of vancomycin in Streptomyces aureus infection. A study[10] simulated the efficacy of vancomycin in Streptomyces aureus infection under different MIC values using a single-compartment pharmacokinetic model and Monte Carlo simulation by including intensive care unit patients; this study concluded that, at an MIC of 1 μg/mL, the daily dose of vancomycin should be at least 3–4 g to achieve a 90% probability of target attainment. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis[11], a high vanco-mycin MIC of ≥ 1.5 μg/mL is related to mortality, and it is difficult to achieve a target AUC/MIC of ≥ 400, especially in MRSA bacteremia once the MIC rises beyond a certain value. This also explains why the clinical efficacy in this case was unsatisfactory when the trough concentration of vancomycin reached the target; it was possibly owing to the AUC/MIC failing to reach the target value with the increase in the MIC value of vancomycin. Second, the tissue penetration was poor. Vancomycin is a water-soluble drug with a small volume of distribution value of 0.4–1 L/kg, and its binding rate to plasma albumin is 10%–50%. As this patient had skin and soft tissue infection, the vancomycin concentration in the skin and soft tissues may have been insufficient.

Under normal circumstances, infections caused by drug-resistant gram-positive cocci can be treated with monotherapies, as drug combinations may increase the incidence of adverse drug reactions and treatment costs. Hence, it is necessary to strictly grasp the indications and avoid misuse of the drug. The best treatment strategy for severe MRSA infections has not yet been determined. The 2011 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the Treatment of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Adults and Children[3] propose that MRSA bloodstream infections that cannot be effectively controlled with a single antibacterial agent should be treated with drug combinations. A high dose of daptomycin combined with other drugs (e.g., gentamicin, rifampicin, linezolid, compound sulfamethoxazole tablets, or anti-Staphylococcus β-lactam antibiotics) can be chosen for combination treatment. Another novel aminomethylcycline antibiotic Omadacycline has a potential role in the treatment of patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) caused by Gram-positive (including MRSA), and as the 2 randomized, controlled studies show Omadacycline had high efficacy and acceptable safety, similar to that of linezolid, in the treatment of ABSSSI caused by gram-positive pathogens, including MRSA[12,13].

Glycopeptide monotherapies have many shortcomings, including poor tissue permeability, slow bactericidal action, and the emergence of drug-resistant strains[14]. Daptomycin, which has a rapid bactericidal effect on MRSA, may be an ideal treatment option[5]. However, daptomycin needs to be administered at a high dose in patients with high MIC[15], and the prognosis is poor[16]. Linezolid is the first marketed synthesized oxazolidinone that can inhibit protein synthesis by affecting the 50S subunit of the bacterial ribosome[6]. In addition, a number of in vitro and in vivo studies as well as case reports have shown the efficacy of daptomycin combined with linezolid. Parra-Ruiz et al[17] reported that linezolid fails to achieve bactericidal activity against MRSA for planktonic bacteria (PB) or biofilm-embedded bacteria (BB) within 72 h in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic biofilm models in vitro. The sustained bactericidal activity of daptomycin on PB was achieved within 48 h, whereas neither daptomycin nor linezolid exerted bactericidal effects on BB. In contrast, when linezolid was used in combination with daptomycin, the bactericidal effect was significantly increased. The combination showed bactericidal activity against PB and BB in 48 h. Therefore, the daptomycin and linezolid combination therapy is more effective than monotherapy using either of them[17]. Similar results were observed using a simulated endocardial neoplasm model[18]. Two recent studies have reported the same result through an in vitro combined drug sensitivity test[19,20]; the synergistic effect was 66%-77% for daptomycin combined with linezolid against MRSA, with no antagonistic effect. We conducted a literature search in PubMed in an attempt to identify all published cases reporting on the efficacy of linezolid and daptomycin combination for MRSA infection. Three cases published in the literature previously were eventually summarized in Table 2. A case report on the effectiveness of this treatment scheme reported, for the first time, a case involving a 62-year-old patient with MRSA bacteremia and MRSA meningitis[21]. Initially, he was administered daptomycin and linezolid because of his allergy to vancomycin. However, the persistent MRSA bacteremia led to the addition of rifampin because of its anti-MRSA activity and its ability to pass through the blood-brain barrier. Finally, his blood cultures were negative after 10 d of admission. In addition, linezolid combined with daptomycin can be used to treat endocarditis caused by MRSA[22]; this was a case of a 26-year-old patient with endocarditis caused by MRSA complicated by pneumonia. The patient was initially treated with vancomycin combined with gentamicin, but vancomycin was switched to daptomycin (8 mg/kg) because of acute renal injury, and linezolid (600 mg every 12 h) was used to treat the MRSA in the lungs. Thirteen days after switching to daptomycin and linezolid, the MRSA bacteremia test results were negative. Another case very similar to the previous one involved a 36-year-old young female with infective endocarditis complicated by a septic pulmonary embolism who had a history of MRSA bacteremia infection that had occurred a year before this infection[23]. The initial treatment plan for this patient was also vancomycin, but the sensitivity to vancomycin decreased on the fourth day of treatment (MIC 2 μg/mL); hence, the treatment was adjusted with linezolid (600 mg every 12 h) and daptomycin (8 mg/kg), and the blood culture result turned negative after 13 d. In this present case, vancomycin was selected as the initial treatment drug. After 9 d of vancomycin treatment, the drain culture continued to be positive, and CT re-examination revealed progression of the abscess. Therefore, the combined treatment of daptomycin and linezolid was started. The peak temperature significantly decreased after the second day, and the drain culture turned negative after 11 d without fever. One month later, the patient was stable and was discharged. These combination therapies may be considered, along with daptomycin and linezolid, following vancomycin treatment failure depending on patient-specific risk factors and hospital formulary constraints. Since combination antimicrobial regimens are not always supported by conclusive trials, further studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of specific combination strategies. These combination therapies may be considered, along with daptomycin and linezolid, following vancomycin treatment failure depending on patient-specific risk factors. Further studies are needed to fully understand the mechanisms of the possible synergistic effects between daptomycin and linezolid.

| Patients | Ref. | Reason for Daptomycin/linezolid use | Host factors | Complication | Prior antimicrobialtherapy | Other active antimicrobials available | Daptomycin/linezolid dose; duration | MIC (mg/mL) | Outcome, follow-up duration |

| 1 | Kelesidis et al[21], 2011 | Allergy | 62 y/o with placement of the coatrial andlumboperitoneal shunts | Meningitis | Daptomycin | Vancomycin | Daptomycin (NS); linezolid (600 mg twice daily); 4 d | Daptomycin (≤ 0.5 μg /mL), vancomycin (1 μg /mL), linezolid (4 μg/mL), rifampin (0.06 μg/mL) | Clinical cure, NS |

| 2 | Yazaki et al[22], 2018 | Allergy, acute kidney injury | 26 y/o woman with surgical closure of ventricular septal defect | Septic pulmonary embolism | Levofloxacin, meropenem, azithromycin, vancomycin, rifampicin, gentamicin | None | Daptomycin (8 mg/kg q48h), linezolid (600 mg q12h); 6 wk | Vancomycin (1 μg/mL), Linezolid (2 μg/mL), Daptomycin (1 μg/mL) | Clinical cure, 2 mo |

| 3 | Galanter et al[23], 2019 | Vancomycin resistance, worsening of septic emboli in both lungs, blood cultures remained positive for MRSA | 26 y/o woman with native tricuspid value endocarditis | Suspected septic embolism | Vancomycin, daptomycin, gentamicin | None | Daptomycin (8 mg/kg iv daily), linezolid (600 mg iv twice daily), 15 d | Daptomycin 1 μg/mL; daptomycin MIC 4 μg/mL (on the 15th day) | Clinical cure, 6 wk |

In conclusion, we report a case of an abscess in the major psoas muscle complicated with pulmonary infection caused by MRSA that was successfully treated with a combination of daptomycin and linezolid. Our experience shows that the combination therapy of daptomycin and linezolid, instead of vancomycin, is an effective alternative therapy for refractory MRSA bacteremia.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Infectious Diseases

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Apiratwarakul K, Surani S S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JL

| 1. | García AB, Candel FJ, López L, Chiarella F, Viñuela-Prieto JM. In vitro ceftaroline combinations against meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol. 2016;65:1119-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bayer AS, Schneider T, Sahl HG. Mechanisms of daptomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: role of the cell membrane and cell wall. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1277:139-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, J Rybak M, Talan DA, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e18-e55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1692] [Cited by in RCA: 2039] [Article Influence: 145.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moore CL, Osaki-Kiyan P, Haque NZ, Perri MB, Donabedian S, Zervos MJ. Daptomycin versus vancomycin for bloodstream infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a high vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration: a case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Seaton RA, Hamed K. Daptomycin: an evidence-based review of its role in the treatment of Gram-positive infections. Infect Drug Resist. 2016;9:47-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | MacGowan AP. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of linezolid in healthy volunteers and patients with Gram-positive infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51 Suppl 2:ii17-ii25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kwak YG, Choi SH, Kim T, Park SY, Seo SH, Kim MB. Clinical Guidelines for the Antibiotic Treatment for Community-Acquired Skin and Soft Tissue Infection. Infect Chemother. 2017;49:301-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Soriano A, Marco F, Martínez JA, Pisos E, Almela M, Dimova VP, Alamo D, Ortega M, Lopez J, Mensa J. Influence of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:193-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 597] [Cited by in RCA: 594] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, Levine DP, Bradley JS, Liu C, Mueller BA, Pai MP, Wong-Beringer A, Rotschafer JC, Rodvold KA, Maples HD, Lomaestro BM. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: A revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77:835-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 732] [Article Influence: 183.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | del Mar Fernández de Gatta Garcia M, Revilla N, Calvo MV, Domínguez-Gil A, Sánchez Navarro A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis of vancomycin in ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:279-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Hal SJ, Lodise TP, Paterson DL. The clinical significance of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration in Staphylococcus aureus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:755-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhanel GG, Esquivel J, Zelenitsky S, Lawrence CK, Adam HJ, Golden A, Hink R, Berry L, Schweizer F, Zhanel MA, Bay D, Lagacé-Wiens PRS, Walkty AJ, Lynch JP 3rd, Karlowsky JA. Omadacycline: A Novel Oral and Intravenous Aminomethylcycline Antibiotic Agent. Drugs. 2020;80:285-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Abrahamian FM, Sakoulas G, Tzanis E, Manley A, Steenbergen J, Das AF, Eckburg PB, McGovern PC. Omadacycline for Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:S23-S32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Davis JS, Van Hal S, Tong SY. Combination antibiotic treatment of serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:3-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Soon RL, Turner SJ, Forrest A, Tsuji BT, Brown J. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic evaluation of the efficacy and safety of daptomycin against Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;42:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ruiz J, Ramirez P, Concha P, Salavert-Lletí M, Villarreal E, Gordon M, Frasquet J, Castellanos-Ortega Á. Vancomycin and daptomycin minimum inhibitory concentrations as a predictor of outcome of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;14:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Parra-Ruiz J, Bravo-Molina A, Peña-Monje A, Hernández-Quero J. Activity of linezolid and high-dose daptomycin, alone or in combination, in an in vitro model of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2682-2685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Steed ME, Vidaillac C, Rybak MJ. Novel daptomycin combinations against daptomycin-nonsusceptible methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an in vitro model of simulated endocardial vegetations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:5187-5192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee YC, Chen PY, Wang JT, Chang SC. A study on combination of daptomycin with selected antimicrobial agents: in vitro synergistic effect of MIC value of 1 mg/L against MRSA strains. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;20:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aktas G, Derbentli S. In vitro activity of daptomycin combined with dalbavancin and linezolid, and dalbavancin with linezolid against MRSA strains. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:441-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kelesidis T, Humphries R, Ward K, Lewinski MA, Yang OO. Combination therapy with daptomycin, linezolid, and rifampin as treatment option for MRSA meningitis and bacteremia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:286-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yazaki M, Oami T, Nakanishi K, Hase R, Watanabe H. A successful salvage therapy with daptomycin and linezolid for right-sided infective endocarditis and septic pulmonary embolism caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Chemother. 2018;24:845-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Galanter KM, Ho J. Treatment of tricuspid valve endocarditis with daptomycin and linezolid therapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76:1033-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |