Published online Feb 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1667

Peer-review started: August 26, 2021

First decision: October 22, 2021

Revised: October 31, 2021

Accepted: December 31, 2021

Article in press: December 31, 2021

Published online: February 16, 2022

Processing time: 168 Days and 17.4 Hours

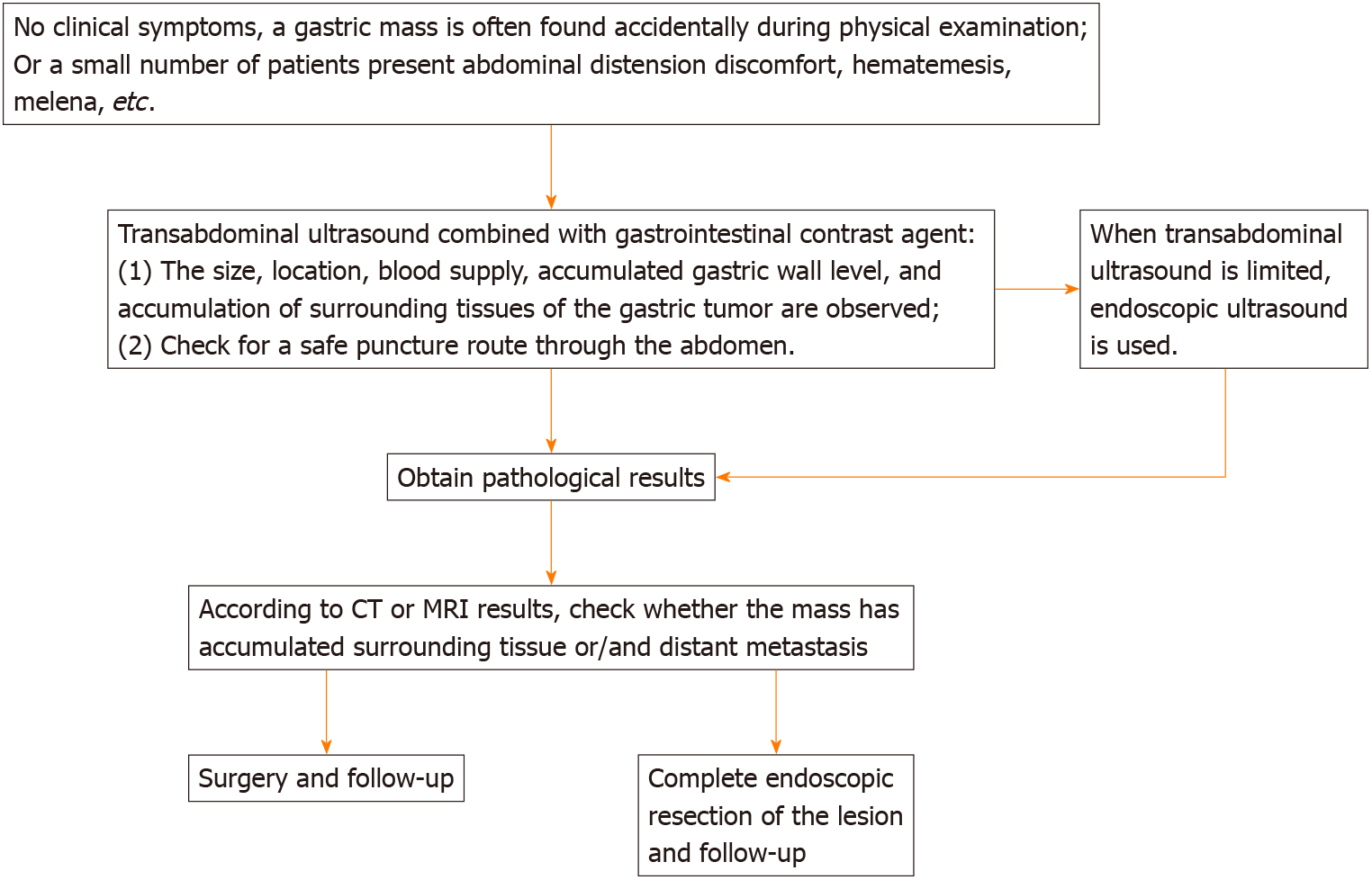

Gastric origin tumors were diagnosed and evaluated preoperatively by gastroscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging. Currently, transabdominal high-resolution ultrasound combined with gastrointestinal contrast agent can be used to diagnose stomach tumors effectively and without invasive procedures or radiation. However, although an appreciable number of cases of gastric schwannoma (GS) have been reported since the first description of such in 1988, the ongoing lack of a comprehensive list of ultrasonic characteristics has limited the accuracy of preoperative ultrasound diagnosis.

A 64-year-old female patient presented to our hospital with dizziness and head discomfort. During an abdominal ultrasound, a hypoechoic gastric mass was found, having clear and regular boundaries and no observable blood flow. Based on these characteristics, a gastrointestinal stromal tumor was suspected. Results from an endoscopic ultrasound biopsy and accompanying immunohistochemical analysis, coupled with abdominal CT findings indicating lymph node enlargement around the stomach, led to diagnosis of GS but did not exclude malignancy. After surgical resection of the tumor, the final diagnosis of GS without lymph node metastasis was made. No recurrence has occurred in the 6 years of follow-up.

A clearly defined ultrasonic characteristic profile of GS is important to improve diagnostic accuracy.

Core Tip: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumor. Since the concept of gastric schwannoma (GS) was proposed in 1988, the incidence of cases has amassed. Transabdominal high-resolution ultrasound combined with abdominal gastrointestinal contrast agent has a unique advantage in gastrointestinal disease diagnosis as it can effectively diagnose tumors non-invasively without radiation. Although ultrasonographic characteristics of GIST have been reported, the literature lacks series of cases of GS and a clear summary of the ultrasonographic characteristics. A summarized ultrasonographic characteristic profile of GS will improve accuracy of differential diagnosis from to other types of gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumor.

- Citation: Li QQ, Liu D. Gastric schwannoma misdiagnosed as gastrointestinal stromal tumor by ultrasonography before surgery: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(5): 1667-1674

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i5/1667.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1667

In the past, gastric tumors were diagnosed by gastroscopy, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). However, with the development of gastrointestinal ultrasound and the use of gastrointestinal contrast agent[1,2], transabdominal high-resolution ultrasound has attracted more clinical attention in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal diseases. Transabdominal high-resolution ultrasound can provide overall information on the lesions, is non-invasive, and does not expose the patient to radiation. In this paper, a patient with a gastric schwannoma was misdiagnosed as gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) by ultrasound before surgery, due in part to a lack of compiled information on the ultrasonic characteristics of GS. As such, we have provided a summarization of the clinical and imaging characteristics of GIST and GS in order to improve the diagnostic accuracy of GS.

A 64-year-old female of Han nationality visited the outpatient clinic on January 19, 2015, after experiencing dizziness and head discomfort for 3 d. The patient had been diagnosed with hypertension for more than 20 years, and at the time of this visit, her blood pressure was 190/100 mmHg.

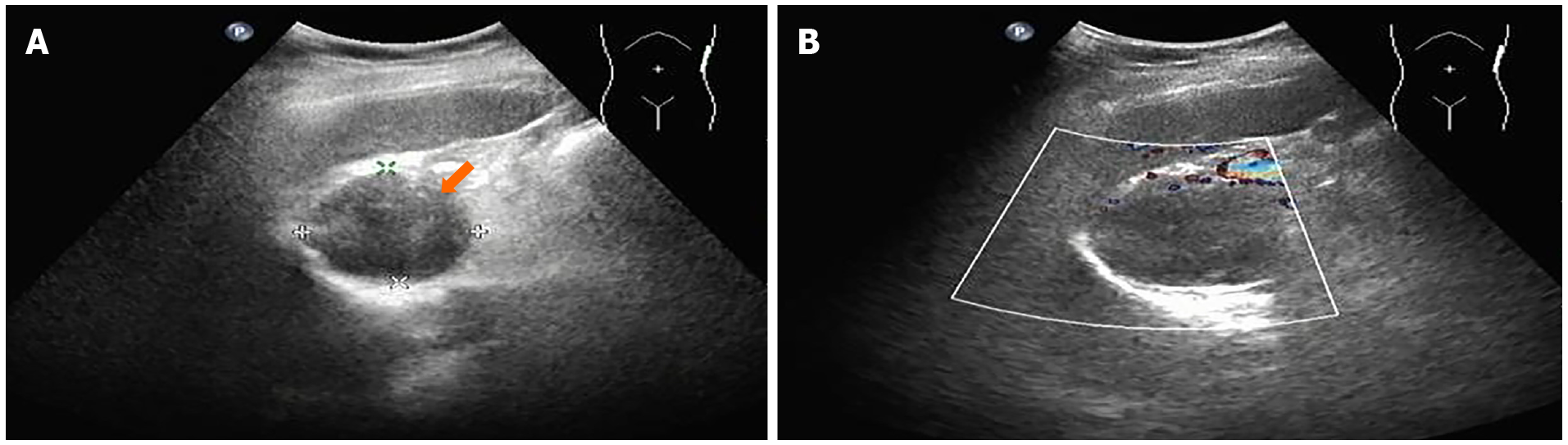

The outpatient doctor performed relevant examinations and advised her to take medication regularly to control blood pressure. The patient also underwent an abdominal ultrasound, which identified a hypoechoic lesion between the upper pole of the spleen and the abdominal aorta that measured 4.7 cm × 4.4 cm, with a clear and regular boundary and no evident blood flow (Figure 1). The ultrasound findings indicated that the lesion had possibly originated from the stomach and was a GIST. The patient presented no abdominal distention, abdominal pain, hematemesis, melena, or dysphagia.

Hypertension for more than 20 years. She took oral nifedipine controlled release tablet 60 mg daily, bisoprolol fumarate tablet 10 mg daily, and indapamide tablet 1.25 mg daily. The patient had no hepatitis B, hepatitis and other infectious diseases.

The patient had no family history of gastrointestinal cancer.

After the patient’s blood pressure was stabilized, she was admitted to the general surgery department for treatment of the gastric tumor. At the time of admittance, her temperature was 36.4 °C, heart rate was 60 beats/min, respiration was 18 breaths/min, and blood pressure was 130/75 mmHg. No enlarged lymph nodes were palpable on either clavicle. The abdomen appeared flat, and no peristaltic waves (in esophagus or stomach) were observed. Upon palpation, the abdomen was soft, with no tenderness, muscle tension, or rebound pain.

Results from routine blood and fecal tests, occult blood test, and blood biochemistry panels were all within normal limits. Tumor marker tests did not reveal any obvious abnormalities.

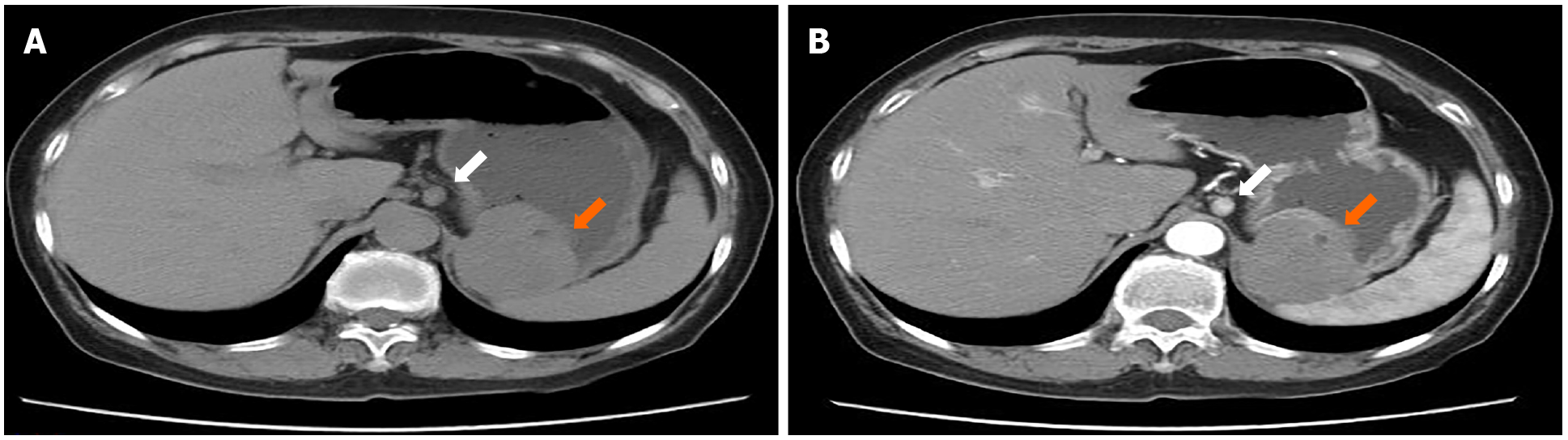

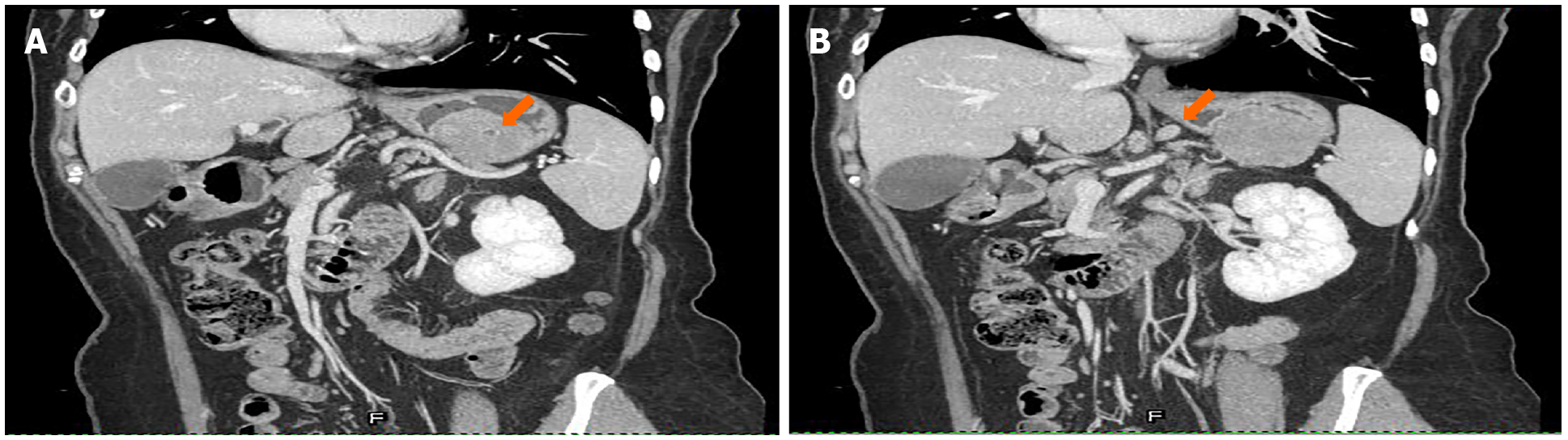

February 5, 2015: Abdominal CT plain and contrast-enhanced scans showed a local soft tissue density mass in the gastric wall with a smooth boundary, sized 5.5 cm × 4.3 cm. There was local protrusion observed outside the contour of the stomach, with obvious enhancement. The surrounding lymph nodes were enlarged, with the larger ones measuring 1.0 cm in diameter. CT did not exclude malignancy (i.e. GIST with peripheral lymph node metastasis) (Figures 2 and 3).

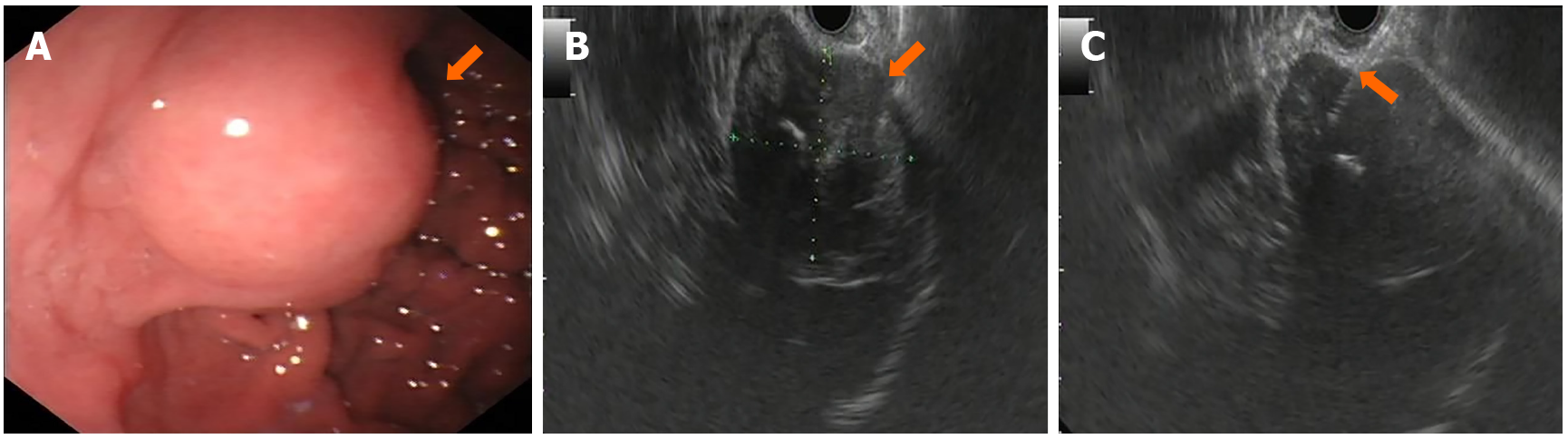

February 10, 2015: Endoscopy confirmed a hemispherical eminence on the fundus of the stomach, with a smooth surface. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed a hypoechoic and heterogeneous mass, sized 3.7 cm × 4.4 cm, derived from the mucous muscularis. Color Doppler showed no evident blood flow. Gastroscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography suggested the possibility of GIST (Figure 4A and B).

February 10, 2015: Fine needle aspiration (FNA) under endoscopic ultrasound guidance (Figure 4C) primarily showed coagulation and calcification, with a small amount of gastric mucosal tissue and few spindle cells, suggesting that spindle cell tumor should be excluded (Table 1).

| Date | Where | Endoscopic ultrasound | FNA pathological | ||||

| Echo | Cumulative level | Homogeneity or not | Border | Blood supply | |||

| February 10, 2015 | Inpatient | Low | Mucosal muscularis | Heterogeneous, with calcification | Smooth | No | Few spindle cells |

| March 4, 2015 | Outpatient | Low | Mucosal muscularis | Heterogeneous, with calcification | Smooth | No | Immunohistochemical examination indicated GS |

March 4, 2015: Since the pathological diagnosis was unclear, the FNA was repeated (again under endoscopic ultrasound guidance). Subsequent immunohistochemical examination was performed and indicated GS (Table 1).

Benign GS.

Given the very few malignant cases of GS reported in the literature[3], and the presence of peripheral lymph nodes indicated by CT in this case, malignant GS was not excluded. Therefore, the patient was admitted to the hospital for elective surgery. An upper abdominal midline incision was made, with a length of about 20 cm. The organs around the lesion were explored. No other abnormality was found in the peritoneum, and no ascites were found. However, a lesion of 4 cm diameter was identified in the anterior wall of the fundus near the greater curvature of the gastric body, with no obvious infiltration of the serous layer. In addition, enlarged lymph nodes were felt around the stomach. As treatment, a radical proximal subtotal gastrectomy was performed (proximal subtotal gastrectomy + radical abdominal lymph node dissection + esophagogastric end-to-end anastomosis) yielding status of R0 (no microscopic residue after resection) and D2 (lymph nodes at the second station completely cleared).

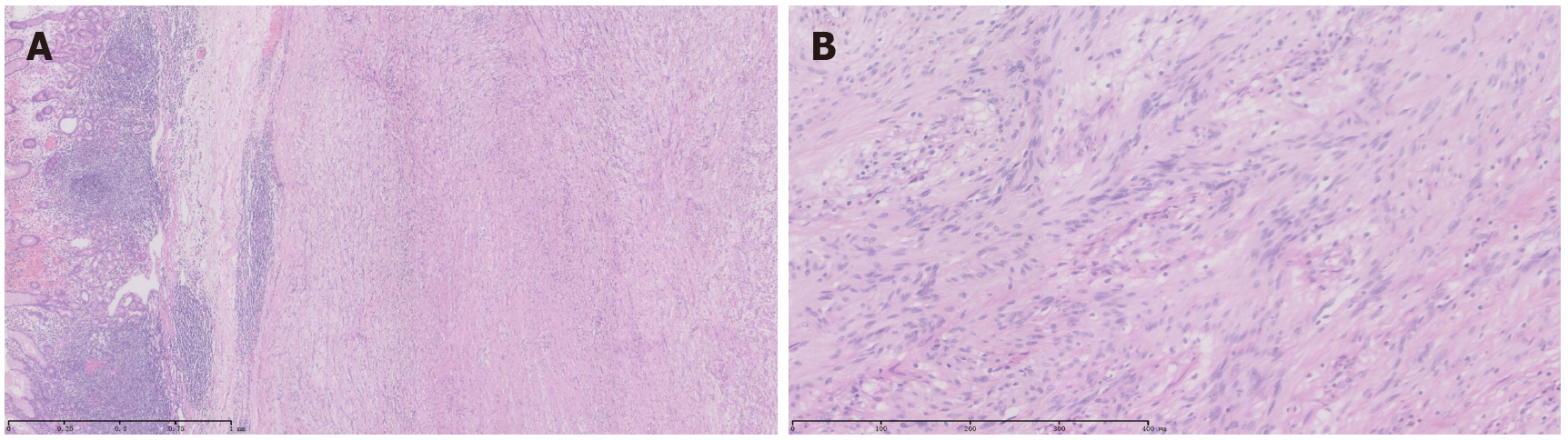

The tumor observed intraoperatively on the anterior wall of the greater curvature of the gastric fundus was a swollen mass, of 6.0 cm × 5.0 cm × 4.5 cm in size, protruding into the serosal side and having a complete capsule and a grayish and yellowish section. Subsequent histological examination defined it as a gastric submucosal spindle cell tumor, with nuclear division of < 5/50 per high power field and immunohistochemistry marker signature of CD117 (-), CD34 (-), DOG-1 (-), S-100 (+), actin (-), and desmin (-). These findings were consistent with GS (Figure 5). A total of 12 large, curved lymph nodes and four small, curved lymph nodes were observed, all of which showed reactive hyperplasia. According to the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) Clinicopathological Classification Guidelines for gastric neoplasms, the clinicopathological stage was T0N0M0. All annual CT re-examinations have shown no recurrence over the 6-year period of follow-up.

GS was first reported by Daimaru et al[4] in 1988. It is a rare tumor of gastric stromal origin, accounting for 0.2% of all gastric tumors and 6.3% of all gastric stromal tumors. GS has a good prognosis and rarely relapses, but malignant lesions have been reported[3,5,6]. GIST is the most common gastric tumor, accounting for about 80% of all[7], followed by gastric leiomyoma, lymphoma, etc. In clinical practice, gastric stromal tumors are generally classified as GIST. Clinically, only 10%-30% of GISTs are malignant, but all GISTs have malignant potential[8,9]. Preoperative differential diagnosis of GS and GIST is difficult, and the auxiliary examinations lack specificity. So far, only pathological and immunohistochemical results are reliable, and genetic tests can be performed when necessary[5].

Upper gastrointestinal angiography, gastroscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography, abdominal CT, abdominal MRI, and other examinations were previously used to diagnose gastric tumors. At present, transabdominal high-resolution ultrasound and gastric contrast agent is routinely applied for the diagnosis of gastric diseases[1,2]. This type of imaging is non-invasive, non-radiative, convenient, fast, repeatable, and safe for the preliminary screening of gastric diseases. Under optimal conditions, it can identify the layered structure of the gastric wall from which the lesions originate. However, to date, transabdominal ultrasound examinations of GS have only been reported in individual case reports, and its ultrasonic characteristics have not yet been clearly summarized.

According to literature reports, a small number of patients have symptoms, such as upper abdominal pain or discomfort, melena, hematemesis, anemia, weight loss, etc., which are mostly seen in female patients aged 50-60 years[5,6,10]. However, most GS patients have no obvious complaints of discomfort. GS is occasionally identified in abdominal ultrasound, abdominal CT, upper gastrointestinal angiography, and gastroscopy. In abdominal ultrasound, the characteristics of GS are local hypoechoic lesion in the gastric wall, with complete mucosal and serous layers and clear boundaries. The lesions are regular or lobulated in shape and lack a blood supply[11]. On CT, GS is characterized by local low-density lesions in the gastric wall, with clear boundaries. The lesions are regular or lobulated and can be enhanced. CT can also provide information about the enlargement of lymph nodes around the lesion. This enlargement is unique to GS but can easily be confused for gastric malignant tumors with peripheral lymph node enlargement[12,13]. Diagnosis of GS is based on immunohistochemical pathology; the tumors are positive for S-100 protein and negative for c-kit, CD34, CD117, actin, desmin, SMA, and DOG-1. Pathological features of GS include spindle cells arranged in bundles in the tumor center and the surrounding lymphocyte sleeve[14]. The lymphocyte sleeve is a characteristic manifestation of GS, and the formation of a lymphocyte mantle may be caused by lymphocyte chemotaxis due to cytokines secreted by tumor cells. This mechanism can also be used to explain why GS is often accompanied by peripheral lymph node enlargement[13].

GIST can occur in any part of the digestive tract but most commonly are found in the stomach (60%-70% of the cases), followed by the small intestine (25%-35%), and the colorectum (5%-10%). Less than 2% of GISTs occur in the esophagus, and a few are found in the mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum[15]. On ultrasound, GIST is characterized by irregular thickening of the gastrointestinal wall. It can present as either isoechoic or hypoechoic and the mass can be spherical, lobulated or irregular, with a clear boundary. The internal echo can be either uniform or uneven, accompanied by anechoic necrosis and have either a rich or poor blood supply[16]. The concept of GIST was proposed by Mazur et a][17] in 1983 based on the differentiation characteristics of tumors. In the past, due to the limitations of pathological techniques and the presence of smooth muscle or nerve bundles in many spindle cell tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, which were similar to other types of tumors in histological morphology, they were considered as smooth muscle or neurogenic tumors and were classified as leiomyoma, leiomyoblastoma, or leiomyosarcoma.

Recent clinical and pathological studies have shown that GIST may originate from astrocytes of the gastrointestinal interstitial region, with special immunophenotype and histological characteristics, and is characterized by multidirectional differentiation, which can differentiate or disorient toward smooth muscle and nerve[18]. Its biological characteristics are difficult to predict. It is, however, classified as a type of gastrointestinal submucosal tumor with malignant potential[8,9]. GIST pathology indicates that cell morphology can be divided into spindle type, epithelioid type, or mixed type, of which spindle cells are the most common[19], but there is no lymphocyte sleeve. Immunohistochemical findings include cells that are positive for CD117, CD34, DOG-1, Ki-67, and succinate dehydrogenase B. C-kit proto-oncogene mutations are common in GIST, mainly in exons 9, 11, 13, and 17. In addition, the PDGFRA gene is also frequently mutated in GIST, mainly in exons 12 and 18[19-21]. GS does not exhibit c-kit proto-oncogene and PDGFRA gene mutations[10].

The gastric wall is divided into five layers under transabdominal high-resolution ultrasound, and the echo from inside to outside is in the order of high-low-high-low-high, corresponding to the interface of the gastric wall and the mucosal epithelium, muscularis mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosal layer, respectively. The origin and level of involvement were determined according to the continuous relationship between the lesion and the five-layer structure of the gastric wall[22]. GS may originate from mucosa or muscularis propria. Gastric cancer primarily includes mucosal neoplasms, originating from the mucosal layer. Other gastric parietal layers are not involved in the early stage, while the whole gastric wall is involved in the late stage. Most GISTs originate from the muscularis propria. Gastric primary lymphoma mainly originates from the mucosa. Gastric nerve fibroma can be isolated nerve fibroma or nerve fibroma disease, and typically involves isolated nerve fibroma from the lower mucosal layer. By identifying the layer of origin, GS may be better distinguished from GIST and other gastric tumors.

The characteristics of gastric wall tumors can be observed by transabdominal high-resolution and endoscopic ultrasonography (Figure 6), with two-dimensional and color Doppler ultrasound. The wall layer that the tumor involves can help to preoperatively determine whether the gastric wall tumor originates from the epithelium or the stroma. If the tumor originates from gastric stroma, GIST should be considered first, and then the possibility of GS should be considered. The reported rate of GS is not very low but the actual incidence remains to be confirmed by large-scale studies. The ultrasound and clinical characteristics of GIST and GS should be actively summarized in future work, in order to provide guidance for the preoperative diagnosis of gastric stromal tumors.

GS are generally benign tumors, and only a few malignant cases have been reported. GS is often accompanied by peripheral lymph node enlargement, which is not an indication of malignancy. In our case, lymph nodes around the lesion were confirmed as reactive hyperplasia, and there was no recurrence during the 6-year follow-up. After the preliminary diagnosis of GS but before confirmation from histopathological tests after surgery, the treatment is as follows: (1) Complete surgical resection is recommended, which can be performed under endoscopy or laparotomy according to the tumor size, location, and relationship with surrounding organs; and (2) Simultaneous resection is recommended for patients with locally enlarged lymph nodes.

We greatly appreciate the patient for allowing us to use the medical documents and information.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Govindarajan KK, Gunay S S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Liu G, Zhong JM, Song PL, Li Y, Zhu JB, Kang HQ, Xu RX. The clinical value of gastrointestinal ultrasound filling combined with contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal diseases. China Health and Nutrition Survey 2016; 8: 32-33. |

| 2. | Zhang Y. A clinical study on the diagnosis of gastric lesions with and without gastrointestinal contrast agent. Shijie Zuixin Yixue Xinxi Wenzhai. 2019;19:147, 169. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Takemura M, Yoshida K, Takii M, Sakurai K, Kanazawa A. Gastric malignant schwannoma presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Daimaru Y, Kido H, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Benign schwannoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:257-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yanagawa S, Kagemoto K, Tanji H, Kodama S, Takeshima Y, Sumimoto K. A Rare Case of Gastric Schwannoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Oncol. 2020;13:330-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mekras A, Krenn V, Perrakis A, Croner RS, Kalles V, Atamer C, Grützmann R, Vassos N. Gastrointestinal schwannomas: a rare but important differential diagnosis of mesenchymal tumors of gastrointestinal tract. BMC Surg. 2018;18:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Hirota S. Differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor by histopathology and immunohistochemistry. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:52-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 852] [Cited by in RCA: 864] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim GH, Ahn JY, Gong CS, Kim M, Na HK, Lee JH, Jung KW, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jung HY. Efficacy of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy in Gastric Subepithelial Tumors Located in the Cardia. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Voltaggio L, Murray R, Lasota J, Miettinen M. Gastric schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 51 cases and critical review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:650-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xu CM, Wang ZG, Li F, Zhong H, Zhang N, Zhou F, Zhu JC, Chen P. Ultrasonographic findings of gastrointestinal schwannoma: 2 cases. Zhongguo Chaosheng Yingxiangxue Zazhi. 2012;21:640-641. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Ji JS, Lu CY, Mao WB, Wang ZF, Xu M. Gastric schwannoma: CT findings and clinicopathologic correlation. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:1164-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wadhawan A, Brady M, LeVea C, Hochwald S, Kukar M. Case reports on a gastric mass presenting with regional lymphadenopathy: A differential diagnosis is gastric schwannoma. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;72:369-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Peltrini R, Greco PA, Nasto RA, D'Alessandro A, Iacobelli A, Insabato L, Bucci L. Gastric schwannoma misdiagnosed as a GIST. Acta Chir Belg. 2019;119:411-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Miettinen M, Majidi M, Lasota J. Pathology and diagnostic criteria of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a review. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38 Suppl 5:S39-S51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xie C, Bo G, Zhang WJ, Wang DW, Wang ZP. Ultrasonography and CT analysis of 32 cases of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Shandong Yiyao. 2015;55:57-59. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Mazur MT, Clark HB. Gastric stromal tumors. Reappraisal of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:507-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jiang YN, Cai X. Research progress in the origin of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Zhongguo Aizheng Zazhi. 2011;21:893-897. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Li Y, Teng Y, Wei X, Tian Z, Cao Y, Liu X, Duan X. A rare simultaneous coexistence of epithelioid gastrointestinal stromal tumors and schwannoma in the stomach: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2019;14:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gopie P, Mei L, Faber AC, Grossman SR, Smith SC, Boikos SA. Classification of gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndromes. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25:R49-R58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Madhala D, Sundaram S, Chinambedudandapani M, Balasubramanian A. Analysis of C-Kit Exon 9, Exon 11 and BRAFV600E Mutations Using Sangers Sequencing in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumours. Cureus. 2020;12:e7369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cao YD, Wen LM. Endoscopic ultrasonography for differential diagnosis and treatment of gastric muscularis propria lesions. M.Sc. Thesis, Southwest Medical University 2018. [cited 26 Aug 2021]. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201802&filename=1018178824.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=fvHjXYk4w5lN-ld6kFmUKWvjsOuNI9xpOiKuVstLvtLuYX3bN2iPtyqlnSeZu94j. |