Published online Feb 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1617

Peer-review started: July 31, 2021

First decision: October 22, 2021

Revised: October 30, 2021

Accepted: December 31, 2021

Article in press: December 31, 2021

Published online: February 16, 2022

Processing time: 194 Days and 6.2 Hours

Hemangioma is a vascular benign tumour of endothelial origin. It appears commonly in the first decade of life with increases incidence in females. Hemangioma is not common to happen in the oral cavity and it is extremely rare to appear in the labial vestibule.

We present a case of an 11-year-old girl who complained of a painful, slowly growing mass which was consistent with the capillary hemangioma in the left mandibular vestibule. Vascular tumor such as hemangioma in the mandibular vestibule is extremely rare; hence, the clinical definitive diagnosis is very challenging. Therefore, radiographic imaging and histopathologic analysis are crucial to reach to the final diagnosis for proper management.

Comprehensive clinical evaluation, proper diagnostic imaging and microscopic analysis of the mass establish a precise diagnosis of the hemangioma for better management.

Core Tip: Although hemangioma rarely occurs in the oral cavity, it should be considered in the diagnosis of a red-bluish isolated mass. In this case report, the patient presented with a painful, slowly growing mass in the left labial vestibule which resulted in asymmetry and swelling of the lower lip. The final diagnosis of the mass was consistent with capillary hemangioma in the mandibular vestibule. Early detection and treatment of oral masses is essential to avoid any complications.

- Citation: Aloyouny AY, Alfaifi AJ, Aladhyani SM, Alshalan AA, Alfayadh HM, Salem HM. Hemangioma in the lower labial vestibule of an eleven-year-old girl: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(5): 1617-1622

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i5/1617.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1617

Hemangioma commonly appears early in life with increases incidence in females more than males. It usually gets smaller with time until it completely disappears. Mulliken et al[1] (1982) published the novel classification of vascular lesion and the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (2018) has provided updated guidelines for vascular anomalies classification. Accordingly, the vascular anomalies have been classified into vascular malformations and vascular tumors. Vascular tumors include non-harmful, locally destructive, and malignant lesions, whereas vascular malformations include simple and combined malformations.

Hemangiomas are vascular benign tumours of endothelial origin, presenting clinically with varying sizes and shapes. In some cases, hemangioma could cause functional disability and disfiguring appearance, which may lead to psychological issues. Histologically, hemangioma has another classification, into either cavernous or capillary types.

Hemangioma is uncommon to occur in the oral cavity and it is extremely rare to appear in the labial vestibule. To our knowledge and based on the review of English literature (PubMed), this case is the first report of capillary hemangioma in the mandibular vestibule. In this report, we present an 11-year-old girl patient complaining of a slowly growing mass that caused labial swelling and asymmetry. The diagnosis was consistent with capillary hemangioma in the mandibular vestibule.

An 11-year-old healthy girl was referred to the oral and maxillofacial surgery clinic for evaluation of labial asymmetry and swelling.

The patient had a two-month-history of a slowly growing lesion in the left side of the lower labial vestibule accompanied with persistent mild pain. The patient and her parents reported no history of trauma at the site of the mass.

The patient was healthy and did not undergo any surgeries.

The parents revealed no significant family history and no genetic abnormalities.

Physical and systemic examination: The patient was healthy and had only taken Tylenol 15 mg as needed for fever.

Extraoral examination: Extraoral examination showed lower lip asymmetry and swelling in the left side.

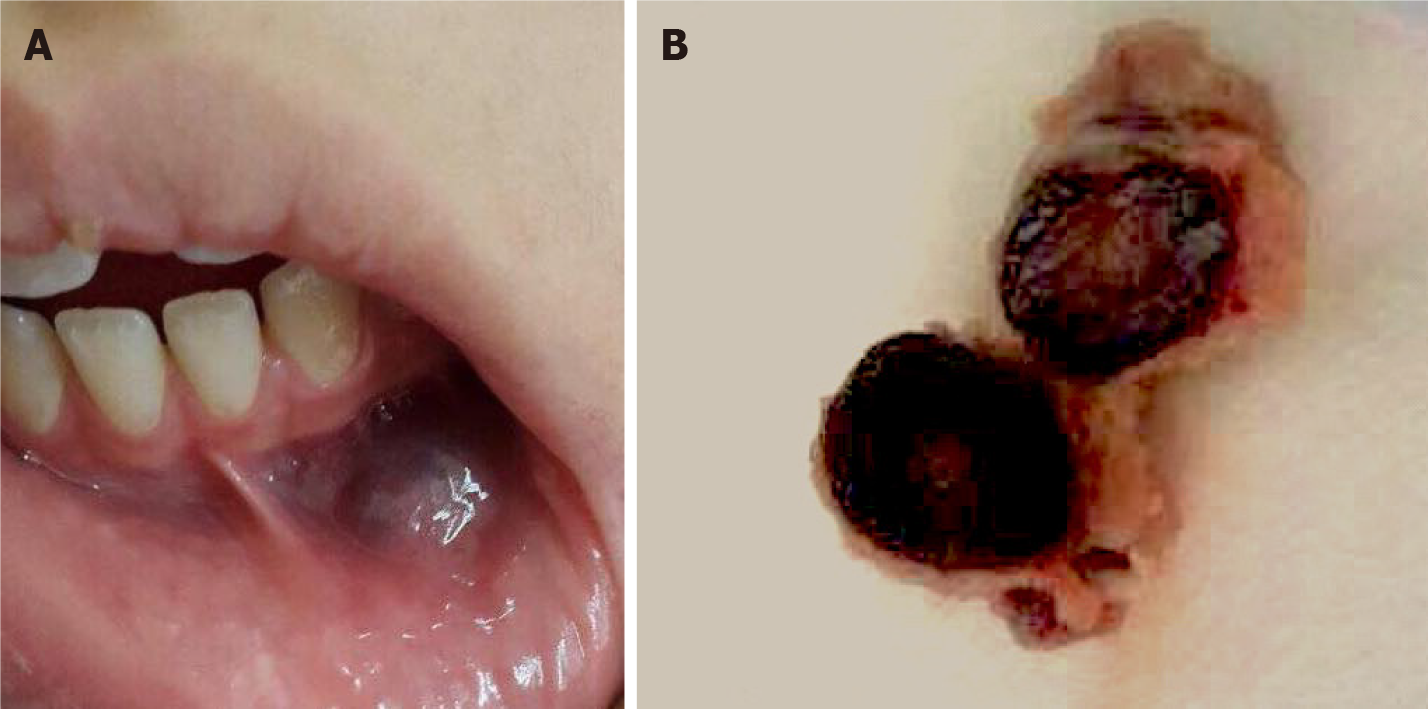

Intraoral examination: Intraoral examination showed a 2.0-1.5 cm, solitary, fluctuant, bluish, smooth, palpable submucosal mass, rubbery in consistency, tender, and blanch on pressure (positive diascopy test). The submucosal mass located in the left mandibular vestibule opposite to tooth number 32 and 33 (23 and 33, according to the FDI World Dental Federation Notation) (Figure 1).

A panoramic radiograph showed normal structures with no significant pathologic findings. Additionally, Color-Doppler-ultrasound was performed to confirm the nature of the lesion. The imaging interpretation revealed a slow-flow vascular lesion in the left lower vestibule and attached to the lower orbicularis oris muscle.

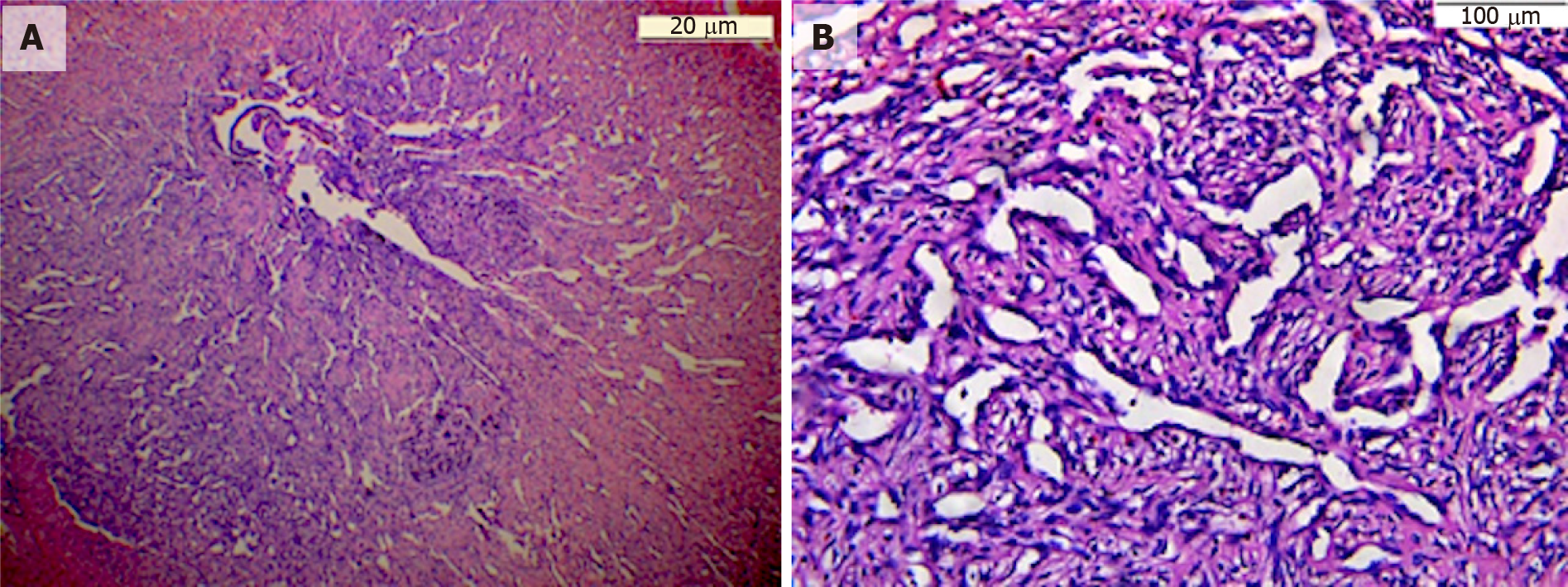

The final diagnosis was based on histopathological analysis. The histopathological diagnosis was consistent with capillary hemangioma in the labial vestibule (Figure 2).

Complete surgical removal of the lesion to reduce the risk of the recurrence.

At two-, four- and eight-week-follow up, the site of the surgery healed well with no sign of bleeding, infection, and swelling. At one- and three-year- follow up, there was no recurrence of the lesion or complications noted. Additionally, the patient was in a good health.

In 1982, vascular anomalies were categorised into two main categories: Vascular malformations and vascular tumors. Hemangiomas are true neoplasms represented by increased rate and proliferation of endothelial cell turnover. On the other hand, vascular malformations are localised abnormality and disorganisation of the blood vessel caused by defects in vascular development[1-3]. Simple vascular malformations are classified histologically, based on the vessel size, into capillary, venous, lymphatics, arteriovenous fistula, and arteriovenous malformations. Vascular lesions are further categorised into non-harmful, locally destructive, and malignant lesions[4]. Namely, hemangioma is a neoplasm of endothelial origin which is commonly found in the early years of life and then the neoplasm regresses gradually with age[5]. Intraoral and intramuscular hemangiomas are rare, dissimilar to cutaneous and subcutaneous hemangiomas. Oral hemangiomas could occur in more than 6% of infants and have high prevalence in female presenting 3:1 (female:male). Infants are more likely to develop oral hemangiomas if they fall in one of the following conditions; infants who are born to older mothers, twins or triplets, premature, or have low birth weight[6]. Hemangioma is a common vascular benign tumor which falls under the category of benign vascular tumors and it is further divided into capillary and cavernous hemangioma[2].

Capillary hemangioma is a common lesion, but it rarely occurs in the oral cavity. According to Matsumoto et al[7], 45.2% of capillary hemangiomas occur on buccal mucosa, 35.5% on the tongue, and only a small percentage occur in the lip, gingiva and palate. Capillary hemangiomas are firm in consistency and have a limited history of symptoms. Although the exact cause of oral hemangioma is not fully understood, hormonal changes, embolic phenomenon and genetic mutations are believed to play an important role in the tumor development[8].

Hemangiomas are hypothesised to develop because of both angiogenesis and vasculogenesis through three different stages, as follows: Endothelial cell proliferation stage, rapid growth stage and spontaneous disappearance. Endothelial cell proliferation is stimulated by many factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta. Then, the quantity of endothelial cells is sustained, and each cell increases in size, leading to comprehensive enlargement of the structure size. At the end, spontaneous involution occurs when the endothelial cells are replaced by connective tissue, adipose, and fibroblast, and the number of small vessels decrease in quantity[9].

Hemangioma could be classified clinically as congenital or infantile (previously named strawberry or juvenile). Congenital hemangioma presents at birth and does not demonstrate proliferation stage. In contrast, infantile hemangioma may develop at the first months of the infant life and show a proliferative phase during the period of six to twelve months; then, most cases spontaneously regress between the age of six to nine years. High percentage of hemangiomas disappear completely in childhood, with < 20% carrying on to puberty[10,11]. Oral hemangioma presents as a solitary, soft, fluctuant, compressible, smooth, red, or bluish submucosal mass. Significant variations may present based on the depth and site of the mass. Superficial masses are easy to visualise and may present as pedunculated, sessile, or lobulated and reddish in colour. In contrast to deeper masses, they appear as a dark blue discolouration recognisable from surrounding normal colour mucosa. It also reveals tenderness on palpation and blanch on compression with glass slide (positive diascopy test)[12]. In this case, the differential diagnosis of the tumor was written down as vascular anomalies, including hemangioma, and vascular malformation, including venous, capillary, lymphatic and arterial malformations. Salivary gland tumor, mucocele and angioleiomyoma were also considered.

It is worth mentioning that vascular malformations, salivary gland tumor, mucocele and angioleiomyoma were all excluded because the lesion showed a slow-flow vascular lesion by using Colour-Doppler-ultrasound, which is highly consistent with hemangioma.

Histological analysis of vascular anomalies, including capillary hemangioma, is still the most acceptable and accurate method of diagnosis[3]. Microscopic description of capillary hemangioma illustrates several dilated capillaries lined by endothelial cells, filled with blood, and surrounded by inflammatory infiltrate.

Hemangioma is mostly characterised by its benign feature and has high tendency of involution by itself over time. However, sometimes hemangioma requires in

Choosing a suitable method for managing hemangioma is based on multiple factors such as the aesthetic consideration, clinical nature, size, site, growth rate, accessibility, extent of the tumor, and age of the patient. Hemangioma could be managed by different ways; for instance, surgical excision of the tumor, embolization, electro

Although hemangioma rarely appears in the oral cavity, it should be considered in the diagnosis of a red-bluish isolated mass. Comprehensive clinical evaluation, proper diagnostic imaging and microscopic analysis of the mass establish a precise diagnosis of the hemangioma for better treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Academy of Oral Medicine.

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Feng J, Zhao GH S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:412-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2357] [Cited by in RCA: 2039] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Merrow AC, Gupta A, Patel MN, Adams DM. 2014 Revised Classification of Vascular Lesions from the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies: Radiologic-Pathologic Update. Radiographics. 2016;36:1494-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Larsen AK, Damsgaard TE, Hedelund L. [Classification of vascular anomalies]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2018;180. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Allen PW, Enzinger FM. Hemangioma of skeletal muscle. An analysis of 89 cases. Cancer. 1972;29:8-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kale US, Ruckley RW, Edge CJ. Cavernous haemangioma of the parapharyngeal space. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;58:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Corrêa PH, Nunes LC, Johann AC, Aguiar MC, Gomez RS, Mesquita RA. Prevalence of oral hemangioma, vascular malformation and varix in a Brazilian population. Braz Oral Res. 2007;21:40-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Matsumoto N, Tsuchiya M, Nomoto S, Matsue Y, Nishikawa Y, Takamura T, Oki H, Komiyama K. CD105 expression in oral capillary hemangiomas and cavernous hemangiomas. J Oral Sci. 2015;57:45-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marchuk DA. Pathogenesis of hemangioma. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:665-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Greenberger S, Bischoff J. Pathogenesis of infantile haemangioma. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:12-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | George A, Mani V, Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:S117-S120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nayak SK, Nayak P. Intramuscular hemangioma of the oral cavity - a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZD41-ZD42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | da Silva WB, Ribeiro AL, de Menezes SA, de Jesus Viana Pinheiro J, de Melo Alves-Junior S. Oral capillary hemangioma: a clinical protocol of diagnosis and treatment in adults. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;18:431-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gianfranco G, Eloisa F, Vito C, Raffaele G, Gianluca T, Umberto R. Color-Doppler ultrasound in the diagnosis of oral vascular anomalies. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ghanem AA, El Hadidi YN. Management of a Life Threatening Bleeding Following Extraction of Deciduous Second Molar Related to a Capillary Haemangioma. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2017;10:166-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barrón-Peña A, Martínez-Borras MA, Benítez-Cárdenas O, Pozos-Guillén A, Garrocho-Rangel A. Management of the oral hemangiomas in infants and children: Scoping review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2020;25:e252-e261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bonet-Coloma C, Mínguez-Martínez I, Palma-Carrió C, Galán-Gil S, Peñarrocha-Diago M, Mínguez-Sanz JM. Clinical characteristics, treatment and outcome of 28 oral haemangiomas in pediatric patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e19-e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stuepp RT, Scotti FM, Melo G, Munhoz EA, Modolo F. Effects of sclerosing agents on head and neck hemangiomas: A systematic review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11:e1033-e1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |