Published online Feb 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1586

Peer-review started: August 13, 2021

First decision: October 22, 2021

Revised: October 30, 2021

Accepted: December 31, 2021

Article in press: December 31, 2021

Published online: February 16, 2022

Processing time: 181 Days and 14.6 Hours

Submucosal protuberance caused by fish bone insertion into the digestive tract has rarely been reported. These cases usually include patients with clear signs such as a history of fish intake, pain, and dysphagia, as well as positive findings on endoscopy and imaging. Here, we report a case of a fish bone hidden in the submucosal protuberance of the gastric antrum during endoscopic submucosal dissection without preoperative obvious positive signs.

A 58-year-old woman presented with epigastric pain for the past 20 d and a submucosal protuberance. Abdominal computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasonography did not indicate the presence of a fish bone. We assumed the cause to be an ordinary submucosal eminence and performed an endoscopic submucosal dissection to confirm its essence. During the operation, a fish bone approximately 20 mm in length was found incidentally.

Our report could potentially prevent the oversight of embedded fish bones and associated adverse effects in patients with similar presentation.

Core Tip: Ingested fish bones appear as high-density shadows and hyperechoic structures on computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasonography scans. Patients typically present with symptoms or positive findings on ancillary examinations. Herein, we present a case of a fish bone hidden in the submucosal protuberance of the gastric antrum without the usual positive signs. In this rare case, we identified the reasons for the fish bone being overlooked in the diagnosis process. This report could potentially prevent the future oversight of embedded fish bones and associated adverse effects.

- Citation: Du WW, Huang T, Yang GD, Zhang J, Chen J, Wang YB. Submucosal protuberance caused by a fish bone in the absence of preoperative positive signs: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(5): 1586-1591

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i5/1586.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1586

Ingestion of foreign bodies (FBs) in the upper digestive tract is a common cause of emergency hospital admissions. Usually, complications do not occur after the FB passes spontaneously through the digestive tract. However, approximately 20% of patients require non-surgical intervention, and less than 1% require surgery[1,2]. Accidental ingestion of fish bones is very common and accounts for 84% of accidental FB ingestions[3]. Cases of FBs embedding in various parts of the digestive tract causing submucosal protuberances are rarely reported. The diagnosis of accidental fish bone retention is usually based on a clear history of fish ingestion; typical symptoms such as pain and dysphagia; and a positive ancillary examination[4,5]. Ingested fish bones are visible as high-density shadows and hyperechoic structures on computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), and are retrievable by ordinary endoscopy. Most previous reports of accidental fish bone ingestion describe patients presenting typical symptoms or positive findings on ancillary examination[6-8]. Herein, we present a case of a fish bone hidden in the submucosal protuberance of the gastric antrum without the usual positive signs.

A 56-year-old woman presented with epigastric pain without heartburn, acid reflux, or abdominal distension and in a good overall condition. Her diet, faeces, and urine were normal, and she had no recent changes in body weight.

The patient experienced epigastric pain for the past 20 d.

The patient had a history of cervical spondylosis and had undergone bilateral pterygium surgery in the past. There was no history of drinking or smoking.

No special personal or family history.

The patient’s vital signs were stable and physical examination was unremarkable.

Preoperative blood tests, such as routine blood examination, liver function, and serum tumour markers of the digestive system, showed no abnormalities.

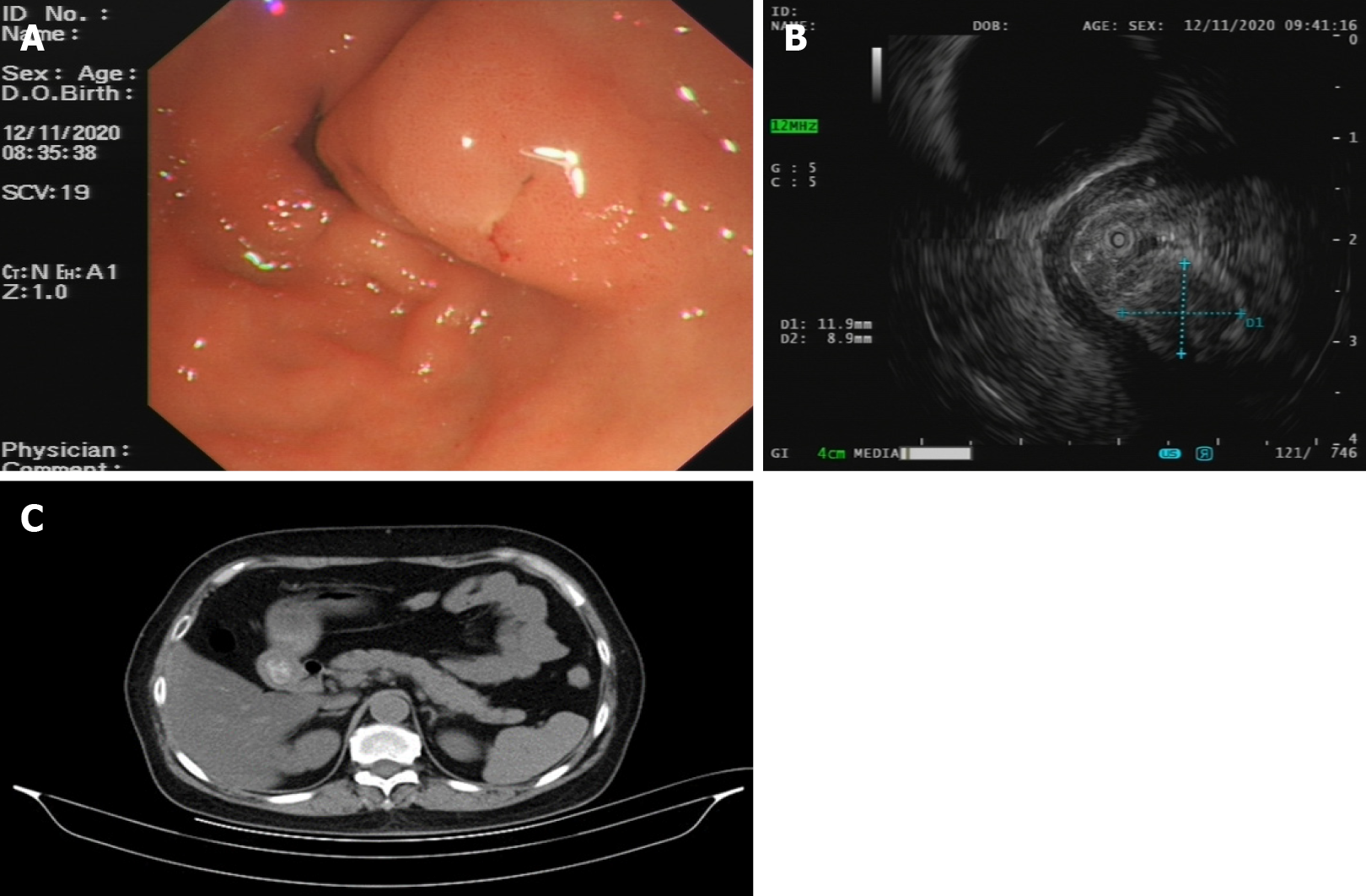

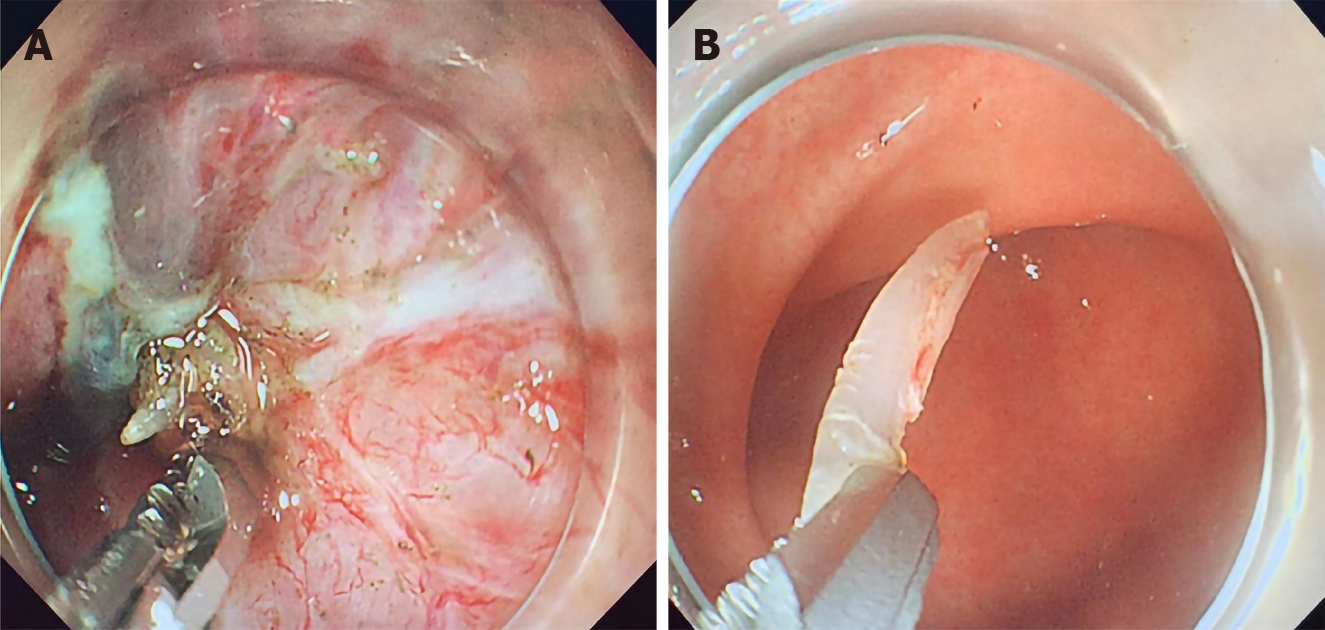

Gastroscopy revealed a submucosal protuberance of the gastric antrum approximately 15 mm in diameter that had a smooth surface, scattered congestion, and an opening at the top (Figure 1A). EUS revealed a submucosal protuberance of approximately 1.19 cm × 0.89 cm (Figure 1B) on the posterior wall of the gastric antrum. The protuberance was round, similar to mixed echogenic masses, predominately hypoechoic with unclear boundaries, and originating from the submucosa. We considered the possibility of a heterotopic pancreas. An abdominal CT scan showed no obvious abnormal thickening or enhancement shadow of the gastric antrum (Figure 1C). Surgical contraindications were absent, and endoscopic submucosal dissection was performed with informed consent from the patient and her family. The lesion was located on the posterior wall of the gastric antrum. After marking and submucosal injection of methylene blue, glycerine fructose, adrenaline, and sodium hyaluronate, the lesion was cut with a dual knife (KD-650L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and peeled off layer by layer. The recovered tissue was biopsied. While inspecting the wound, a strip of white foreign body was found under the wound that could not be pulled out using forceps (Figure 2A).

The final diagnosis of the present case was a fish bone submucosal protuberance of the gastric antrum.

The fish bone, approximately 20 mm in length, was removed using a dual knife (Figure 2B), and the wound was clamped with a haemostatic clamp. No perforation or bleeding was observed, and the operation was concluded. Postoperatively, a gastric tube was placed for continuous gastrointestinal decompression. The patient underwent primary nursing, fasting, acid suppression (Esomeprazole Sodium 40mg ivgtt bid), haemostasis (Aminocaproic Acid and Sodium Chloride lnjection 100 mL ivgtt qd), infection prevention (Cefuroxime Sodium 0.75 g ivgtt temporary twice), and fluid replacement. There were no changes in intervention and without other concurrent interventions.

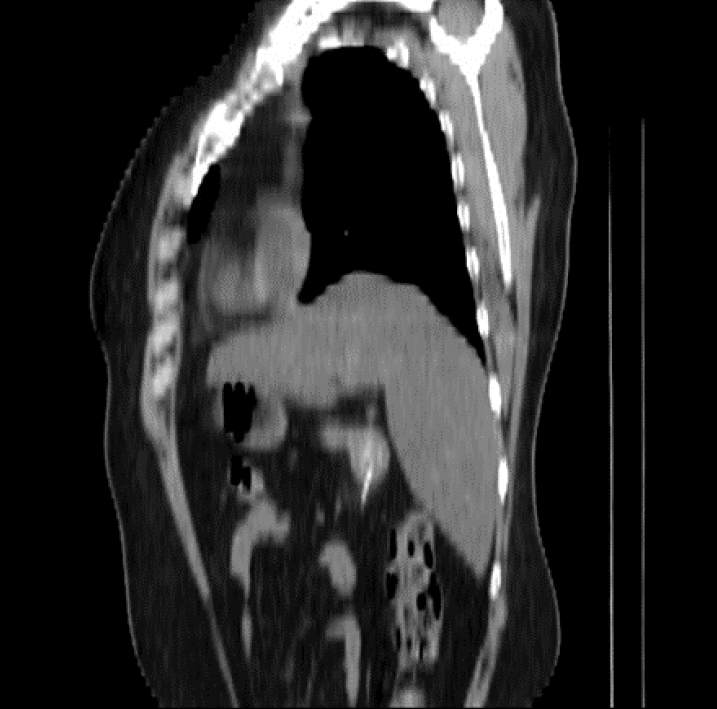

Pathology results revealed hyperplastic polyps of the antral mucosa with irregular, dilated, hyperaemia of the vascular lumen in the lamina propria. Unexpected discovery of the fish bone prompted us to question the patient again for a more detailed history. The patient recollected having recurrent epigastric pain as early as 6 years after eating fish with no effective diagnosis or examination. We proceeded by inviting senior radiologists to review the patient’s imaging studies. Upon careful review, the radiologists noticed a dot-like high-density shadow, which indicated a fish bone approximately 2.0 cm long on CT reconstruction (Figure 3). Finally, the patient improved and discharged.

The present case helps to highlight the importance of careful surgical wound inspection. In our case, the patient denied any recent ingestion of fish and diagnostic exams including endoscopy, CT, and EUS also showed no evidence of fish bones. A surgeon is most likely to think of a common submucosal protuberance as the likely aetiology given the present clinical scenario. Left unnoticed, the fish bone may form an inflammatory hyperplastic protuberance and cause recurring abdominal pain in the patient again. In more severe cases, delayed perforation, mediastinal abscess, or even severe fatal peritonitis can occur[9,10]. Therefore, careful inspection of the surgical wound is a critical step in uncovering possible embedded fish bones or other FBs in the mucosa.

Gastric submucosal protuberances are often asymptomatic and are found accidently by gastroscopy due to other diseases. Acute abdominal pain, fever, or acute submucosal changes on gastroscopy, especially purulent changes, are signs that often alert clinicians to the possibility of FB ingestion. In our case, the patient presented with chronic abdominal pain, and the lesion seen on endoscopy had a smooth mucosa similar to the submucosal uplift caused by a stromal tumour, heterotopic pancreas, or leiomyoma. In view of these findings, the possibility of FB ingestion would rarely be considered. Few reported cases of digestive tract protuberances were caused by fishbone, and most were accompanied by abdominal pain[1,11]. Therefore, patients with chronic abdominal pain and submucosal protuberance must also be questioned regarding any intake of fish or FBs. Such questioning takes an extremely short time. When a patient’s history is indicative of fishbone intake, surgeons need to be careful in peeling off the submucosal protuberance to avoid cutting the fishbone too short and thus requiring additional surgery, which will eventually bring burden and risk to the patients.

When hard FBs such as fish bones, jujube shells, or chicken bones enter the gastric cavity accidentally or are pushed into the open gastric space during endoscopy, they may be discharged from the body spontaneously through the peristaltic movements of the digestive tract[12]. In cases where the FB is sharp in nature, embedding into the gut can occur, which may lead to serious complications and unavoidable surgery. Thus, timely removal of the FB is perhaps more conducive to long-term patient prognosis.

There may be several reasons why the patient in our case did not show any obvious signs of fish bone ingestion upon ancillary examination. First, ingested fish bones are usually very small, and the superficial changes can easily be mistaken as calcifications and surgical suture[13], or ignored altogether due to the influence of gastric content. Second, if the fish bone was from a cartilaginous species of fish, it would have low density on CT and be hypoechogenic on EUS, thus making it difficult to differentiate it from surrounding soft tissue and hard to identify using CT imaging modalities. Third, when the length of the fish bone is perpendicular to the CT scan section, the punctuate changes seen would evade conclusive diagnosis. In one study, thoracic CT revealed an irregular high-density shadow in an oesophageal mucosal lesion[1], which was ultimately identified as a fish bone structure by three-dimensional CT reconstruction. Therefore, CT reconstruction is mandatory in scanning such lesions. Fourth, careful EUS examination of every gastrointestinal protuberance in all directions including longitudinal as well as transverse scanning during radial or linear echoendoscopic examination should be emphasized to avoid missing such fish bones.

Ingested fish bones appear as high-density shadows and hyperechoic structures on CT tomography and EUS, and patients typically present with symptoms or positive findings on ancillary examinations. Herein, we present a case of a fish bone hidden in the submucosal protuberance of the gastric antrum without the usual positive signs. Thus, the size, type, and course of the fish bone, as well as the diligence of the doctor, may all play a role and affect the patient’s eventual outcome and clinical course.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Okasha HH S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Cao L, Chen N, Chen Y, Zhang M, Guo Q, Chen Q, Cheng B. Foreign body embedded in the lower esophageal wall located by endoscopic ultrasonography: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Barkai O, Kluger Y, Ben-Ishay O. Laparoscopic retrieval of a fishbone migrating from the stomach causing a liver abscess: Report of case and literature review. J Minim Access Surg. 2020;16:418-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Venkatesh SH, Venkatanarasimha Karaddi NK. CT findings of accidental fish bone ingestion and its complications. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2016;22:156-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Erbil B, Karaca MA, Aslaner MA, Ibrahimov Z, Kunt MM, Akpinar E, Özmen MM. Emergency admissions due to swallowed foreign bodies in adults. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6447-6452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ambe P, Weber SA, Schauer M, Knoefel WT. Swallowed foreign bodies in adults. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:869-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang Z, Du Z, Zhou X, Chen T, Li C. Misdiagnosis of peripheral abscess caused by duodenal foreign body: a case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xie R, Tuo BG, Wu HC. Unexplained abdominal pain due to a fish bone penetrating the gastric antrum and migrating into the neck of the pancreas: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:805-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jimenez-Fuertes M, Moreno-Posadas A, Ruíz-Tovar Polo J, Durán-Poveda M. Liver abscess secondary to duodenal perforation by fishbone: Report of a case. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:42. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Geng C, Li X, Luo R, Cai L, Lei X, Wang C. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: a retrospective study of 1294 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:1286-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malick KJ. Endoscopic management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2013;36:359-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shan GD, Chen ZP, Xu YS, Liu XQ, Gao Y, Hu FL, Fang Y, Xu CF, Xu GQ. Gastric foreign body granuloma caused by an embedded fishbone: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3388-3390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kikuchi K, Tsurumaru D, Hiraka K, Komori M, Fujita N, Honda H. Unusual presentation of an esophageal foreign body granuloma caused by a fish bone: usefulness of multidetector computed tomography. Jpn J Radiol. 2011;29:63-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Traynor P, Stupalkowska W, Mohamed T, Godfrey E, Bennett JMH, Gourgiotis S. Fishbone perforation of the small bowel mimicking internal herniation and obstruction in a patient with previous gastric bypass surgery. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:rjaa369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |