Published online Feb 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1557

Peer-review started: August 12, 2021

First decision: October 20, 2021

Revised: November 9, 2021

Accepted: December 31, 2021

Article in press: December 31, 2021

Published online: February 16, 2022

Processing time: 183 Days and 3.7 Hours

The results of intensive statin pretreatment before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is inconsistent between Chinese and Western populations, and there are no corresponding meta-analyses involving hard clinical endpoints in the available published literature.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of high-dose statin loading before PCI in Chinese patients through a meta-analysis.

Relevant studies were identified by searching the electronic databases of PubMed, Embase and Cochrane’s Library to December 2019. The outcomes included an assessment of major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), cardiac death, target vessel revascularization (TVR), myalgia /myasthenia and abnormal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in all enrolled patients. Random effect model and fixed effect model were applied to combine the data, which were further analyzed by χ2 test and I2 test. The main outcomes were then analyzed through the use of relative risks (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (95%CI).

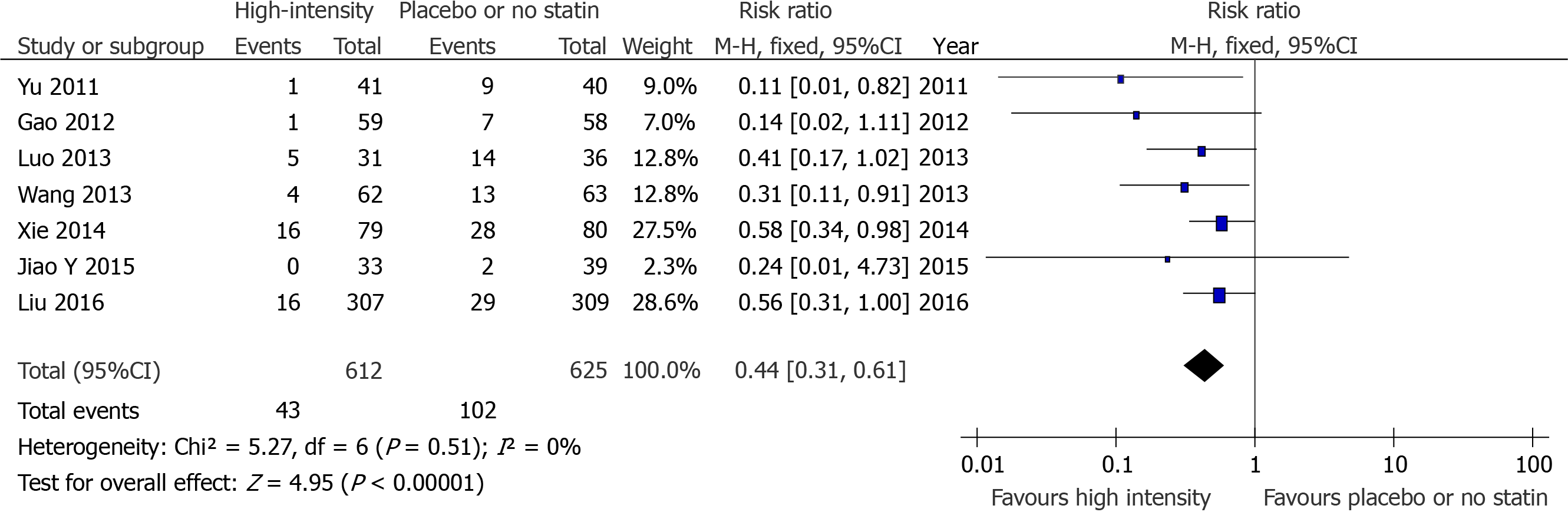

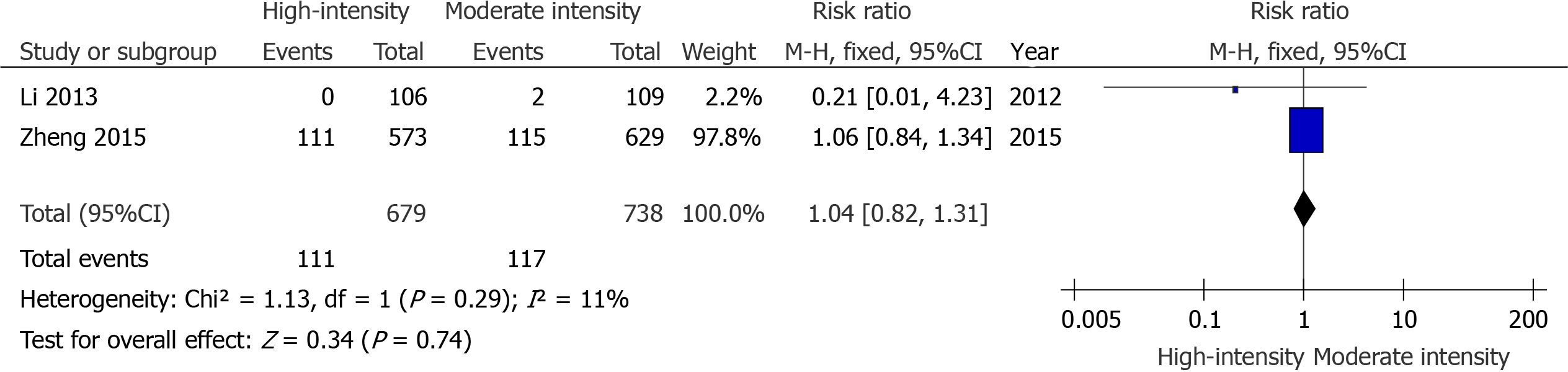

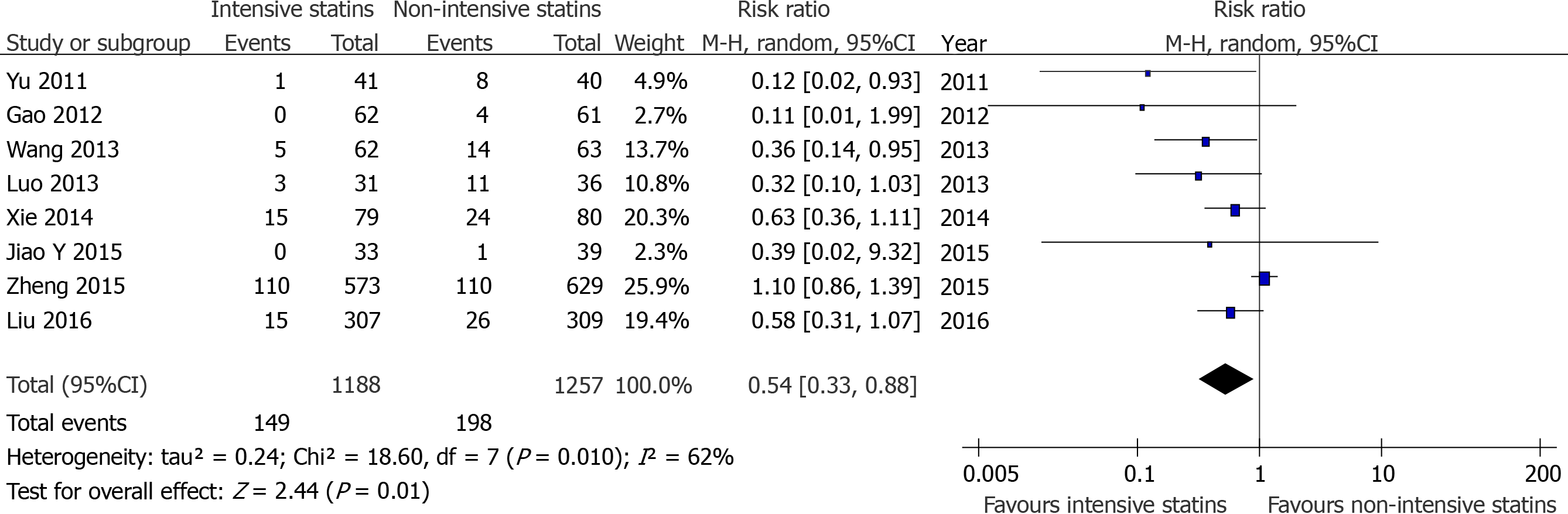

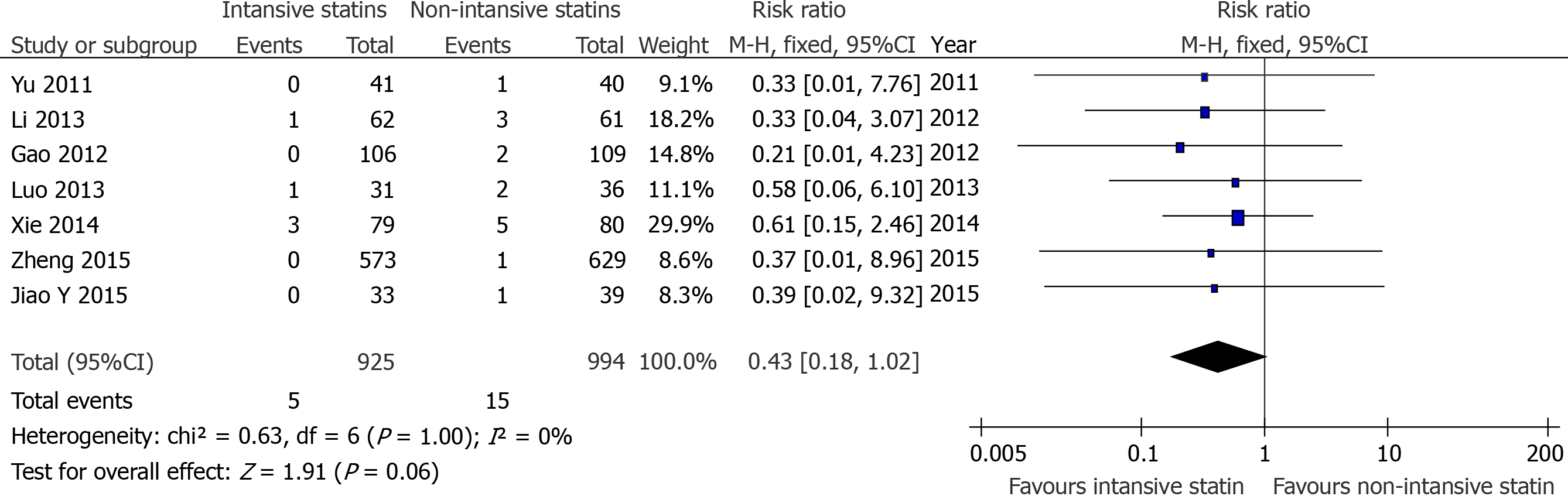

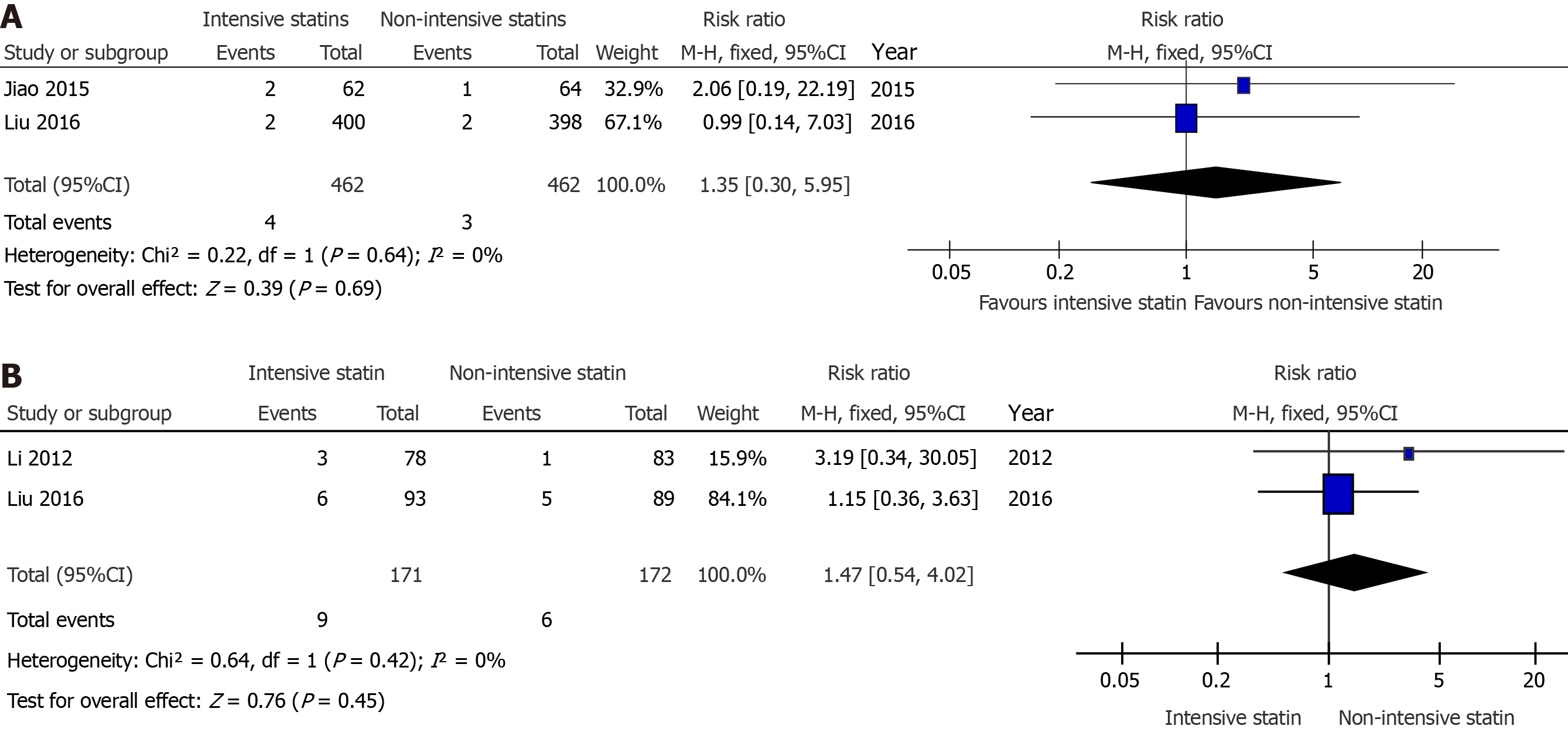

Eleven studies involving 3123 individuals were included. Compared with patients receiving placebo or no statin treatment before surgery, intensive statin treatment was associated with a clear reduction of risk of MACE (RR = 0.44, 95%CI: 0.31-0.61, P < 0.00001). However, compared with the patients receiving moderate-intensity statin before surgery, no advantage to intensive statin treatment was seen (RR = 1.04, 95%CI: 0.82-1.31, P = 0.74). In addition, no significant difference was observed between intensive statin therapy and non-intensive statin therapy on the incidence of TVR (RR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.18-1.02, P = 0.06) , myalgia /myasthenia (RR = 1.35, 95%CI: 0.30-5.95, P = 0.69) and abnormal alanine aminotransferase (RR = 1.47, 95%CI: 0.54-4.02, P = 0.45) except non-fatal MI (RR = 0.54, 95%CI: 0.33-0.88, P = 0.01).

Compared with placebo or no statin pretreatment, intensive statin before PCI displayed reduced incidence of MACE. However, there was no significant benefit between high and moderate-intensity statin. In addition, no significant difference was observed between intensive statin therapy and non-intensive statin therapy on the incidence of TVR, myalgia/myasthenia and abnormal alanine aminotransferase except non-fatal MI.

Core Tip: As the cornerstone of primary and secondary prevention of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease, statins have been widely used in clinical practice. However, whether intensive statin therapy before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) could benefit the Chinese population remains debatable. A meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the strategy. The results showed that compared with placebo or no statin pretreatment, Chinese patients receiving intensive statin therapy before PCI could further reduce the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events. In addition, there was no significant benefit to using high-intensity and moderate-intensity statin therapy.

- Citation: Yang X, Lan X, Zhang XL, Han ZL, Yan SM, Wang WX, Xu B, Ge WH. Intensive vs non-intensive statin pretreatment before percutaneous coronary intervention in Chinese patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(5): 1557-1571

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i5/1557.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1557

At present, the burden of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease is very heavy in China. There are about 290 million patients presenting with these conditions, including 11 million patients with coronary heart disease[1]. Despite the rapid development of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which has increased from 500000 in 2014 to more than 915000 in 2018, and also surpassed the numbers of presenting cases in the United States[2], the overall mortality rate of coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction in China is still on the rise[1]. This suggests that there is room for optimizing perioperative therapy.

As the cornerstone of primary and secondary prevention of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease, statins have been widely used in clinical practice. In recent years, a number of studies in Europe and the United States suggested that intensive statin therapy before PCI could significantly reduce the level of postoperative myocardial damage markers and reduce the incidence of perioperative myocardial infarction and short-term cardiovascular events[3-5].

However, whether the strategy could benefit the Chinese population remains debatable. The ALPACS study, which included the Chinese population, suggested that patients did not benefit from intensive statin therapy as compared with a control population in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (P = 0.80)[6]. The ISCAP study also found no difference in the incidence of MACE between treatment with high-intensity and moderate-intensity statins after 30 d and 6 mo of follow-up (P = 0.43 and P = 0.63, respectively)[7]. Considering the differences in lipid metabolism between Chinese and Western populations, it was unknown whether or not race influ

This current article intended to evaluate the efficacy and safety of intensive statin therapy as compared to non-intensive statin pretreatment before PCI in the Chinese population through a meta-analysis investigation.

A comprehensive search of electronic databases including PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library was performed by two researchers. The search was limited from inception of the database collections up to December 2019 and of the English language. Search terms included “intensive,” “intensity,” “high,” “load,” “loading,” “statin,” “atorvastatin,” “rosuvastatin,” “percutaneous coronary intervention” and “PCI” and connected using the logical search modifiers “AND” or “OR” in standard Boolean search strategies. It is worth mentioning that in order to inadvertently avoid missing important literature, the retrieval type did not include some terms such as “China” or “Chinese.” We checked the location of the research center and the specific inclusion criteria in the article to comprehensively determine that the patient was indeed Chinese. The references of the identified articles and relevant reviews were screened to include other potentially suitable trials.

Studies satisfying the following criteria were eligible: (1) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (2) The patient was Chinese; (3) The patient presented with an emergency or elective PCI; (4) Preoperative interventions for intensive and non-intensive statin therapy, which included moderate-intensity statin therapy, placebo and no statin pretreatment; (5) High-intensity statin therapy that referred to atorvastatin ≥ 40 mg/d or rosuvastatin ≥ 20 mg/d and moderate-intensity statin therapy that referred to atorvastatin < 40 mg/d or rosuvastatin < 20 mg/d or an equivalent dose of the statin; (6) Outcome indicators that included effectiveness and safety of the treatment. The former referred to MACE and the latter referred to myalgia/myasthenia and abnormal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. MACE is defined as cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) and target vessel revascularization (TVR). Abnormal ALT is defined as ALT levels that increased more than three-fold the upper limit of the normal reference range; (7) The follow-up lasted for 1-3 mo after PCI; and (8) The published literature language was English. Exclusion criteria included any of the following: chronic high-intensity statin therapy before PCI; abnormal liver enzymes [ALT or aspartate aminotransferase that exceeded 40 U/L]; blood creatinine levels > 2 mg/dL; or a history of muscle disease. The studies were reviewed by two independent investigators to determine whether they met the set inclusion criteria. In the case of any disagreement, this was resolved by consensus.

The baseline data involving study characteristics (i.e. first author, year of publication, sample size, intervention and follow-up time), patient characteristics (i.e. clinical presentation and statin medication history) and outcome indicators were extracted directly from the articles. Differences in assessments were resolved by discussion with a third investigator.

The RCTs were evaluated according to the following methodological criteria as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration: sequence generation, concealment of allocation, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias.

We used RevMan (Version 5.3; Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and Stata software (version 12.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, United States) for meta- and statistical analyses. Dichotomous data were presented as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The heterogeneity was evaluated using I2 and a P value that was based on the χ2 test. I2 ≤ 50% or P ≥ 0.1 did not demonstrate significant heterogeneity, and a fixed-effects model was used. I2 > 50% or P < 0.1 indicated significant heterogeneity, and thus a randomeffects model was applied. Potential publication bias was assessed with a funnel plot and Egger’s regression asymmetry test. All P values were twosided, and the results were considered statistically significant at an alpha value of P < 0.05.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Xue B, who is an assistant researcher from the department of Cardiology, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital.

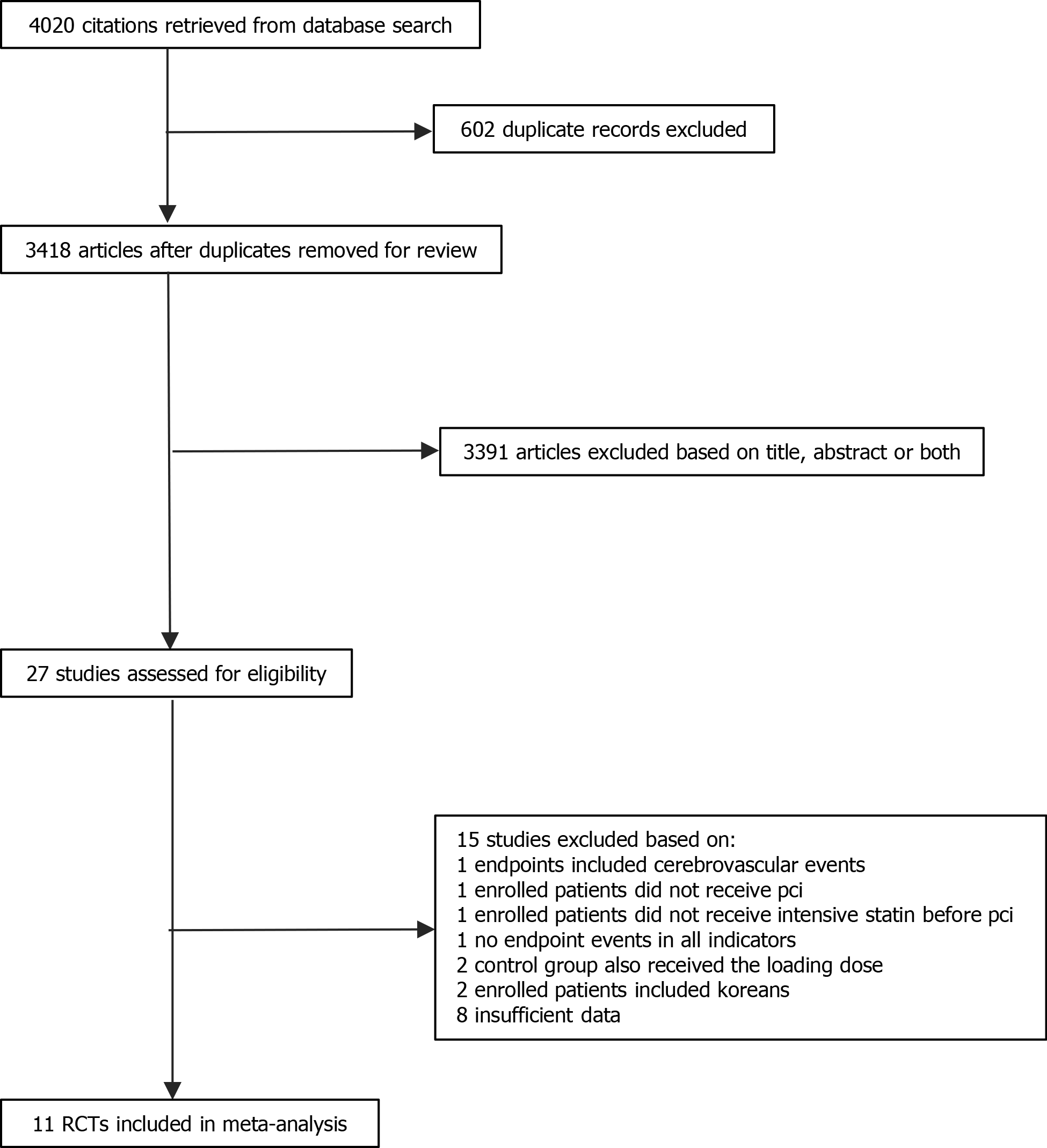

As shown in Figure 1, 4020 potentially relevant articles were identified in the initial analysis. Among them, 3418 articles were identified after removal of duplicate studies. Only 27 articles were retained after screening the title and abstract. Of note, one study was excluded as there was zero occurrence of each of the six conditions considered in both treated and control[9]. Finally, 11 studies involving 3123 patients were included in the present metaanalysis[7,10-19]. Among them, 1524 patients belonged to the intensive statin treatment group, and 1599 patients belonged to the non-intensive statin treatment group. Furthermore, the non-intensive statin treatment group that received moderate-intensity statin therapy, the placebo group and the no statin pretreatment group, included 738, 244 and 617 patients, respectively. All patients were female in one study[17]. A meta-analyses was not performed for cardiac death because of an extremely low occurrence, only one case in all studies. The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. The baseline clinical, angiographic and procedural characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 2. Quality assessment results are described in Table 3.

| Ref. | Sample size (intensive/non-intensive statin) | Clinical presentation | Statin medication history | Primary/elective PCI | Statin regimen before PCI | Statin regimen after PCI | Follow-up (d) | Outcome indicators | |

| Effectiveness | Safety | ||||||||

| Liu et al[10], 2016 | 616 (307/309) | Stable angina, ACS | Statin-naïve or atorvastatin ≤ 20mg/d, or equivalent dose statin | Elective PCI | Atorvastatin 80 mg 12 h before PCI vs no statin pretreatment | 40 mg/d vs 20 mg/d | 30 | MACE, non-fatal MI | Myalgia/ |

| 182 (93/89) | STEMI | Statin-naïve or atorvastatin ≤ 20mg/d, or equivalent dose statin | Primary PCI | Atorvastatin 80 mg just before primary PCI vs no statin pretreatment | 40 mg/d vs 20 mg/d | 90 | ALT | ||

| Jiao et al[11], 2015 | 72 (33/39) | NSTE-ACS | Not mentioned | Elective PCI | Rosuvastatin 20 mg 12 h before PCI + 20 mg just before PCI vs no statin pretreatment | 10 mg/d | 30 | MACE, cardiac death, non-fatal MI, TVR | |

| Jiao et al[12], 2015 | 126 (62/64) | NSTE-ACS | Not mentioned | Elective PCI | Rosuvastatin 20 mg 12 h before PCI + 20 mg just before PCI vs no statin pretreatment | 10 mg/d | 30 | Myalgia/myasthenia | |

| Zheng et al[7], 2015 | 1202 (573/629) | Stable angina, NSTE-ACS | Statin-naïve or atorvastatin ≤ 20mg/d or equivalent dose statin | Elective PCI | Atorvastatin 80 mg at night before PCI for 2 d vs atorvastatin ≤ 20 mg or equivalent dose statin at night before PCI | 40 mg/d vs ≤ 20 mg/d or equivalent dose statin | 30 | MACE, cardiac death, non-fatal MI, TVR | |

| Xie et al[13], 2014 | 159 (79/80) | NSTE-ACS | Statin-naïve | Elective PCI | Rosuvastatin 20 mg 12 h before PCI + 20 mg 2 h before PCI vs no statin pretreatment | 10 mg/d | 30 | MACE, cardiac death, non-fatal MI, TVR | |

| Luo et al[14], 2013 | 67 (31/36) | NSTE-ACS | Statin-naïve | Elective PCI | Rosuvastatin 20 mg 12 h before PCI + 20 mg 2 h before PCI vs no statin pretreatment | 10 mg/d | 30 | MACE, cardiac death, non-fatal MI, TVR | |

| Wang et al[15], 2013 | 125 (62/63) | NSTE-ACS | Statin-naïve | Elective PCI | Rosuvastatin 20 mg 2-4 h before PCI vs placebo 2-4 h before PCI | 10 mg/d | 30 | MACE, cardiac death, non-fatal MI, TVR | |

| Li et al[16], 2013 | 215 (106/109) | Stable angina | Regular statin for at least 3 mo | Elective PCI | Atorvastatin 80 mg 12 h before PCI vs 20 mg 12 h before PCI | 20 mg/d | 30 | MACE, cardiac death, non-fatal MI, TVR | |

| Gao et al[17], 2012 | 117 (59/58) | NSTE-ACS | Statin-naïve | Elective PCI | Rosuvastatin 20 mg 12 h before PCI + 10 mg 2 h before PCI vs placebo 12 h before PCI + 2 h before PCI | 10 mg/d | 90 | MACE, cardiac death, non-fatal MI, TVR | |

| Li et al[18], 2012 | 161 (78/83) | STEMI | Statin-naïve | Primary PCI | Atorvastatin 80 mg 1.5 h before PCI vs placebo 1.5 h before PCI | 40 mg/d | 30 | ALT | |

| Yu et al[19], 2011 | 81 (41/40) | NSTE-ACS | Statin-naïve | Elective PCI | Atorvastatin 80 mg 12 h before PCI + 40 mg 2 h before PCI vs placebo 12 h before PCI + 2 h before PCI | 20 mg/d | 30 | MACE, cardiac death, non-fatal MI, TVR | |

| Variable | High-intensity statin/population (%) | Moderate-intensity statin/population (%) | Placebo or no statin pretreatment/population (%) |

| Number of patients | 1524/3123 (48.8) | 738/3123 (23.6) | 861/3123 (27.6) |

| Male | 1052/1524 (69.0) | 521/738 (70.6) | 566/861 (65.7) |

| Hypertension | 9441524 (61.9) | 489/738 (66.3) | 533/861 (61.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 439/1429 (30.7) | 232/758 (30.6) | 246/778 31.6) |

| Dyslipidemia | 193/751 (25.7) | 147/649 (22.7) | 75/201 (37.3) |

| Smokers | 537/1524 (35.2) | 279/758 (36.8) | 280/881 (31.8) |

| Previous MI | 88/610 (14.4) | 0/20 (0) | 84/632 (13.3) |

| Previous PCI | 159/1183 (13.4) | 51/629 (8.1) | 103/612 (15.2) |

| Previous CABG | 6/500 (1.2) | 0/0 (0) | 6/496 (1.2) |

| Stable angina | 230/506 (45.5) | 109/109 (100) | 118/398 (29.6) |

| NSTE-ACS | 518/767 (67.5) | 0/0 (0) | 539/778 (69.3) |

| STEMI | 203/478 (42.5) | 0/20 (0) | 204/501 (40.7) |

| Single vessel | 59/172 (34.3) | 0/20 (0) | 55/200 (27.5) |

| Double vessel | 66/172 (38.4) | 0/20 (0) | 71/200 (35.5) |

| More than three and triple vessels | 47/172 (27.3) | 0/20 (0) | 54/200 (27.0) |

| Target vessel LM | 36/877 (4.1) | 25/629 (4.0) | 7/320 (2.2) |

| Target vessel LAD | 622/1018 (61.1) | 418/649 (64.4) | 249/483 (51.6) |

| Target vessel LCX | 328/1018 (32.2) | 199/649 (30.7) | 155/483 (32.1) |

| Target vessel RCA | 346/1018 (34.0) | 234/649 (36.1) | 164/483 (34.0) |

| B2/C lesions | 346/609 (56.8) | 0/0 (0) | 333/615 (54.1) |

| Multivessel lesions | 33/78 (42.3) | 0/0 (0) | 39/83 (47.0) |

| Multivessel intervention | 244/773 (31.6) | 215/629 (34.2) | 62/201 (30.8) |

| Aspirin | 1375/1491 (92.2) | 622/738 (84.3) | 802/822 (97.6) |

| Clopidogrel/Ticlopidine | 1300/1385 (93.9) | 541/629 (86.0) | 807/822 (98.2) |

| β-blockers | 1104/1491 (74.0) | 495/738 (67.1) | 630/822 (76.6) |

| ACEI/ARB | 1045/1491 (70.1) | 404/738 (54.7) | 667/822 (81.1) |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 89/350 (25.4) | 0/20 (0) | 101/380 (29.7) |

| DES | 822/851 (96.6) | 701/738 (95.0) | 176/179 (98.3) |

| Ref. | Randomization sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other sources of bias |

| Liu et al[10], 2016 | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Jiao et al[11], 2015 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Jiao et al[12], 2015 | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Zheng et al[7], 2015 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Xie et al[13], 2014 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Luo et al[14], 2013 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Wang et al[15], 2013 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Li et al[16], 2013 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Gao et al[17], 2012 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Li et al[18], 2012 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Yu et al[19], 2011 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

There were seven studies that compared the effects of preoperative high-intensity statin therapy and placebo or no statin therapy on the incidence of MACE[10,11,13-15,17,19]. The results showed that the incidence of MACE (RR = 0.44, 95%CI: 0.31-0.61, P < 0.00001, Figure 2) between the two groups were statistically significant. In addition, there were two studies that compared the effects of preoperative high-intensity statin therapy and moderate-intensity statin therapy on the incidence of MACE[7,16]. The indicator was not statistically significant (RR = 1.04, 95%CI: 0.82-1.31, P = 0.74, Figure 3).

Due to the limitations of the included literature, it was difficult to perform meta-analysis between the high-intensity statin group with placebo or no statin group or moderate-dose statin group in non-fatal MI and TVR. Therefore, we compared intensive statin therapy and non-intensive statin therapy for these endpoints. The results showed that the incidence of TVR[7,12-14,16,17,19] (RR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.18-1.02, P = 0.06, Figure 4) between the two groups were not statistically significant, whlie there was a significant difference in the incidence of non-fatal MI[7,10,11,13-15,17,19] (RR = 0.54, 95%CI: 0.33-0.88, P = 0.01 Figure 5).

There were two studies that compared the effects of preoperative intensive statin therapy and non-intensive statin therapy on the incidence of myalgia/myasthenia[10,12] and abnormal ALT[10,18]. No significant difference was observed between the groups (RR = 1.35, 95%CI: 0.30-5.95, P = 0.69, Figure 6A; RR = 1.47, 95%CI: 0.54-4.02, P = 0.45, Figure 6B, respectively).

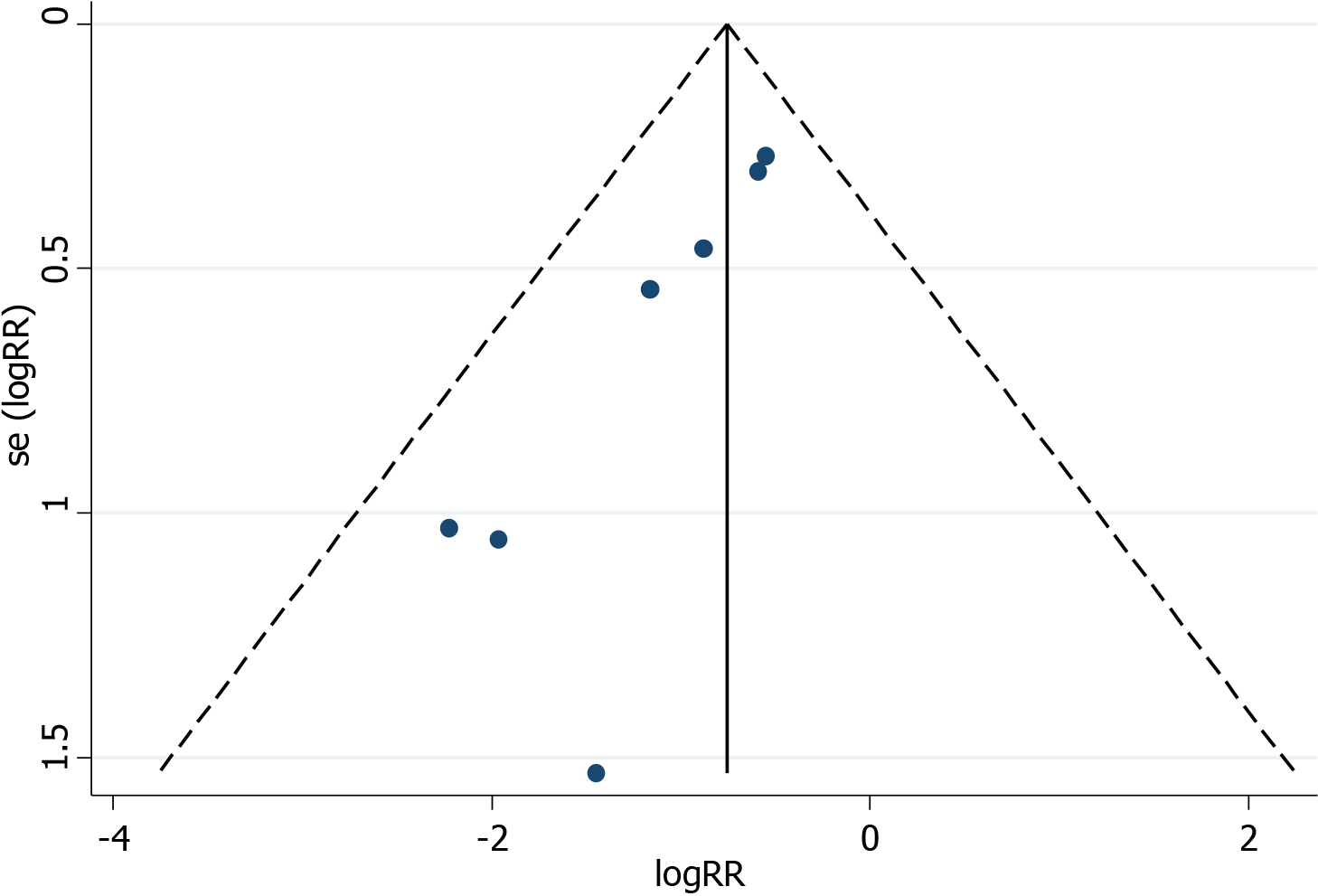

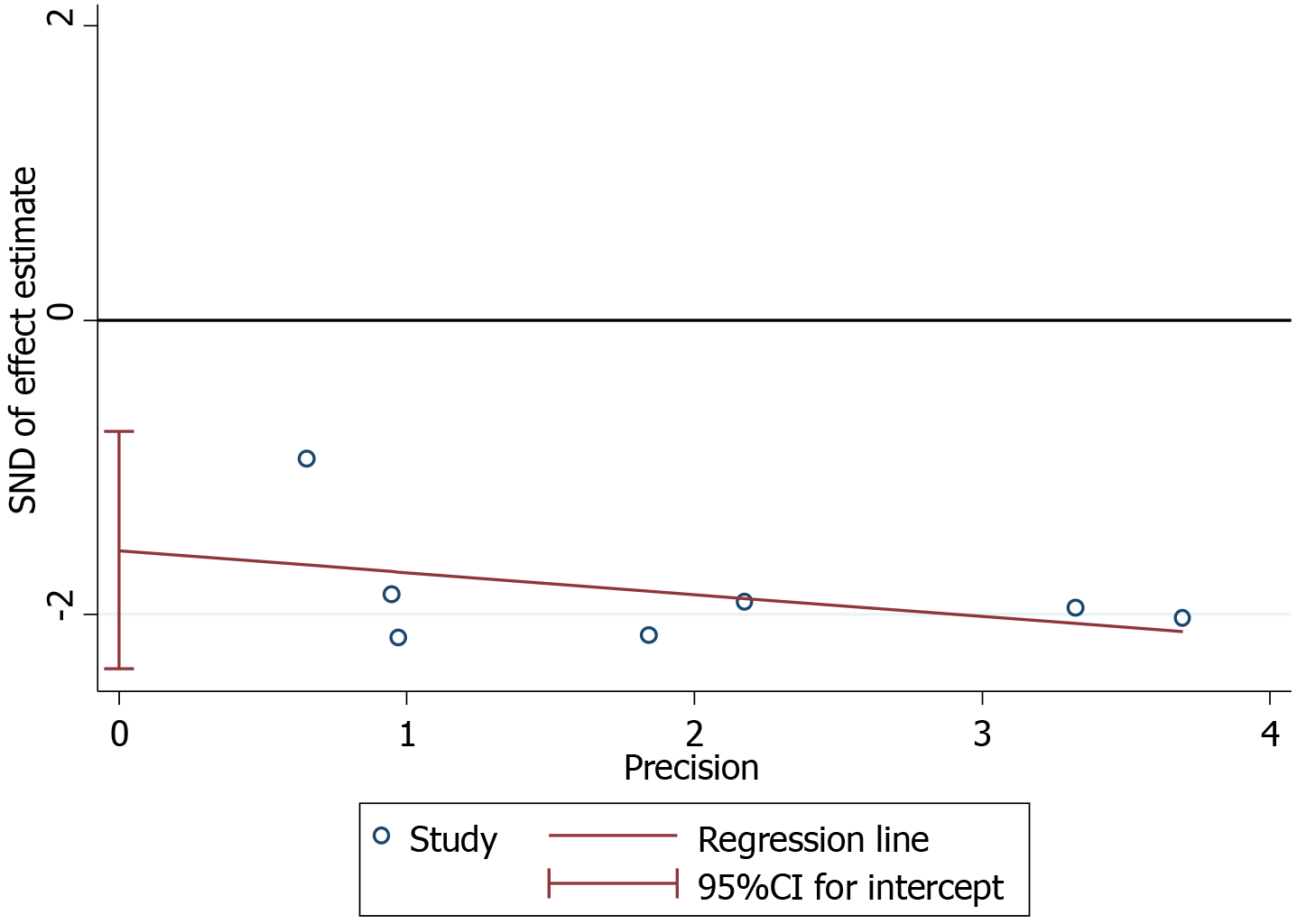

The plots were symmetrical on visual inspection, indicating a risk of publication bias (Figure 7). Egger’s regression test also demonstrated risk of publication bias (P = 0.004; Figure 8). The small number of studies included in the overall population and subgroup might represent one of the key reasons for publication bias.

Some studies have completed investigations of intensive statin therapy before PCI. In 2013, the ALPACS study took the lead in exploring similar work in Asia[6]. This was a prospective, multicenter, randomized, open-label study involving 499 patients with Non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (26 clinical centers in China and South Korea). None of the enrolled patients had previously received statins. The intensive treatment group received additional atorvastatin loading doses of 80 mg at 12 h and 40 mg at 2 h pre-PCI. The conventional treatment group was only treated with atorvastatin at a dose of 40 mg/d after PCI. The results suggested that the intensive treatment group failed to significantly reduce the occurrence of MACE at 30 d after PCI as compared with the conventional treatment group (15.7% vs 14.7%; P = 0.80). The study also demonstrated that the Asian population could tolerate high-intensity atorvastatin during the perioperative period.

Unfortunately, the ALPACS were not included in this meta-analysis because of the mixed data from the Korean population. The ISCAP study that was subsequently published in 2015 was a large-scale, multicenter, randomized, prospective, open-label, blinded, parallel controlled clinical study with Chinese patients[7]. Follow-up results showed no significant differences in the incidence of MACE at 30 d when comparing the intensive statin treatment group and the conventional treatment group (19.4% vs 18.3%; P = 0.43). When followed up at 6 mo, there was still no difference between the groups (20.1% vs 18.3%; P = 0.63). In terms of safety, no significant differences were found in terms of liver enzymes, creatine kinase levels and other objective indicators.

In addition to multicenter clinical studies, many scholars have attempted to identify further answers with meta-analyses. In 2013, Guo[20] conducted a meta-analysis on the impact of sequential statin therapy on the prognosis of Chinese patients with PCI. Ten studies that included 1015 patients were investigated. The results from that published study suggested a significant reduction in the incidence of MACE within 6 mo. Since some patients in the experimental group only received intensive statin treatment after PCI, the subjects were not entirely consistent with the characteristics discussed in this paper. In 2017, a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 11 RCTs with 802 patients was performed by Ye et al[21]. Compared with preoperative rosuvastatin 10 mg/d therapy, it was found that using a loading dose of 20 mg/d before PCI significantly reduced cardiac troponin T and high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels by 24 h and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol and triglyceride levels by 30 d after PCI. However, the clinical indicators that were analyzed and evaluated in this article were surrogate indicators, which did not involve cardiovascular endpoint events nor did they examine the safety. In 2018, Cao et al[22] discussed the effectiveness of high-dose statin therapy before PCI in reducing cardiovascular events in Asian populations. The systematic review included 7 RCTs involving 1381 patients, all of whom were Chinese or Korean. The results indicated that the incidence of MACE and perioperative MI in the intensive statin group were significantly lower than those in the control group. This article did not discuss the benefits of treatment to the Chinese population through subgroup analysis.

Compared with the previously published meta-analysis, this article was improved in the following ways. First, four new studies published after 2014 were included in this paper[7,10-12]. The full paper included 11 RCTs with 3123 patients, which meant that the total number of studies and patients exceeded any previously published meta-analysis. Second, the population studied in this paper were all Chinese; thus, the interference of other Asian populations such as inclusion of the Korean population was removed. Third, new outcome indicators such as TVR were established to make the data more complete.

An important finding of this study is that the benefits of differential treatment were inconsistent. Compared with patients receiving placebo or no statin treatment before surgery, intensive statin treatment was associated with a clear reduction of risk of MACE. This conclusion was consistent with the results of previous studies involving Western populations. However, compared with the patients receiving moderate-intensity statin before surgery, no advantage to intensive statin treatment was seen, which suggested that both regimens promoted a consistent effect on short-term outcomes. In fact, there is a lack of data on the effect of high-intensity and moderate-intensity statins in Western populations.

Racial differences in the pharmacokinetics of statins have also been reported. With a single dose of 20 mg or 40 mg rosuvastatin, the area under the curve and peak blood concentration of Chinese patients were 1.79, 1.89, 2.31 and 2.36 times that of Caucasians, respectively[23,24]. Birmingham also found that relative to Caucasians the mean area under the curve was 86% higher for single oral doses of rosuvastatin 20 mg and 53% higher for atorvastatin 40 mg in Chinese subjects. In addition, the geometric mean maximum drug concentration was proportionally higher for each statin[25]. Differences in race sensitivity to statins might also be related to genetic factors. Common polymorphisms in genes encoding drug transporters such as ABCB1, ABCG2 and SLCO1B1 between Chinese and Caucasian populations might partially account for this phenomenon[26]. However, based on the results of this paper and those of prior studies, we did not find any racial differences in terms of the efficacy and safety of preoperative intensive statin therapy.

Another thing that introduces attention was that the data for the meta-analysis comparing high-intensity statins and moderate-intensity statins virtually all come from one study: ISCAP, which was the largest clinical study to date targeting Chinese patients. Although negative results were obtained, we also noticed there might be some confounding factors that affected the final conclusions. First, about 60% of enrolled patients had previously taken low-intensity and even moderate-intensity statins, and only 40% were statin-naïve patients. It was unclear whether statin history could have dampened the benefits from the effects of intensive treatment in Chinese patients. Secondly, the timing of drug administration in ISCAP was performed at night before the operation, and it was not exactly fixed. Distinct from the aforementioned observations, the timing was found to be 2-4 h or 12 h before elective PCI and was relatively fixed in other trials[9-12,14-17,19]. On the one hand, the regimen in ISCAP was more consistent with actual clinical practice. On the other hand, it was uncertain whether the timing of statin administration could affect the benefits of intensive statin therapy. Finally, the characteristics of patients enrolled in ISCAP were a higher proportion of multiple lesions, higher average number of stents, longer average length of stents and a higher incidence of MACE at 30 d following PCI; all indicated that the complexity of a coronary lesion might reduce the effectiveness of high-dose statin treatment.

The guidelines and consensus underwent a process of deeper understanding on whether the patients should receive preoperative intensive statin therapy in the Chinese population. Based on evidence from Western populations, expert consensus that was released in 2014 recommended that all patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing PCI, including emergency and elective PCI, should initiate high-dose statin treatment immediately before PCI, such as treatment with atorvastatin 80 mg/d[27]. Furthermore, since ALPACS and ISCAP were published in succession, guidelines issued in 2016 concluded that in the absence of additional evidence of high-quality RCTs with hard endpoints, it was not recommended that acute coronary syndrome patients receive intensive statin therapy before PCI[28,29]. The results of this meta-analysis were consistent with the recommendations of the guidelines and further strengthened the foundations of evidence-based medicine.

This current article has the following limitations and deficiencies: (1) The quality of the included studies were generally not high, and the evidence was not sufficiently robust. The included RCTs were single-center studies and lacked rigorous trial design with the exception of ISCAP, which was not described in detail in randomization, blinding and data analysis. We also need to recognize that ISCAP was an open-label trial. Although it had all of the outcome events adjudicated by a blinded Clinical Event Committee group and all laboratory tests were done by blinded laboratory staff, the investigators and subjects were not blinded to the treatment arms of this trial. As such, both might tend to report more adverse events in the experiment arm, and this might subsequently lead to increased withdrawal from the study in this group. This trend could still have some undesirable effects on the results of the study. Hence, more studies with a sufficient level of statistical power are needed to investigate the effects of high-dose statin loading before PCI in the context of Chinese patients; (2) Subgroup analysis was not performed. Limited by the included literature, we did not implement subgroup analysis involving some factors, such as statin medication history (i.e. patients with chronic statin therapy or statin-naïve patients), categories of statin (i.e. atorvastatin or rosuvastatin), timing of statin administration (12 h before surgery or at other times) and the timing of revascularization (emergency PCI or elective PCI). It is also crucial to further explore the limitations by dividing the population into different subgroups as described above; and (3) Due to the lack of RCTs in Western popu

Available evidence suggested that when compared with placebo or no statin pretreatment, Chinese patients receiving intensive statin therapy before PCI have a reduced incidence of MACE. However, there was no significant benefit on using high-intensity and moderate-intensity statin therapy. In addition, no significant difference was observed between intensive statin therapy and non-intensive statin therapy on the incidence ofTVR, myalgia/myasthenia and abnormal ALT except non-fatal MI. To summarize, our findings indicated that it may be reasonable for Chinese patients to receive at least moderate-intensity statin pretreatment before commencing PCI.

At present, the burden of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease is very heavy in China. Despite the rapid development of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the overall mortality rate of coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction in China is still on the rise. This suggests that there is room for optimizing perioperative therapy.

In China, patients with acute coronary syndrome regularly received intensive statin (such as atorvastatin 40 mg/d or rosuvastatin 20 mg/d) after PCI. Because of the very limited data, the guidelines do not give a positive recommendation for preoperative intensity statin therapy, which was inconsistent with Western people. As members of the medical team in a Coronary Care Unit, we are eager to know if intensive statin before PCI can benefit Chinese patients.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of intensive statin therapy as compared to non-intensive statin pretreatment before PCI in the Chinese population through a meta-analysis investigation.

Relevant studies were identified by searching the electronic databases of PubMed, Embase and Cochrane’s Library to December 2019. The outcomes included an assessment of major adverse cardiovascular events, non-fatal myocardial infarction, cardiac death, target vessel revascularization, myalgia/myasthenia and abnormal alanine aminotransferase in all enrolled patients. Random effect model and fixed effect model were applied to combine the data, which were further analyzed by χ2 test and I2 test.

Compared with patients receiving placebo or no statin treatment before surgery, intensive statin treatment was associated with a clear reduction of risk of major adverse cardiovascular events [risk ratio (RR) = 0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.31-0.61, P < 0.00001]. However, compared with the patients receiving moderate-intensity statin before surgery, no advantage to intensive statin treatment was seen (RR = 1.04, 95%CI: 0.82-1.31, P = 0.74). In addition, no significant difference was observed between intensive statin therapy and non-intensive statin therapy on the incidence of target vessel revascularization (RR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.18-1.02, P = 0.06) , myalgia/myasthenia (RR = 1.35, 95%CI: 0.30-5.95, P = 0.69) and abnormal alanine aminotransferase (RR = 1.47, 95%CI: 0.54-4.02, P = 0.45) except non-fatal myocardial infarction (RR = 0.54, 95%CI: 0.33-0.88, P = 0.01).

Our finding was significant that when compared with placebo or no statin pretreatment, intensive statin before PCI displayed reduced incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events. However, there was no significant benefit between high and moderate-intensity statin.

It is likely to promote at least the use of moderate-intensity statin before PCI instead of no statin pretreatment in Chinese patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lee PN S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Hu S, Gao R, Liu L, Zhu M, Wang W, Wang Y, Wu Z, Li H, Gu D, Yang Y, Zheng Z, Chen W. Summary of the 2018 Report on Cardiovascular Diseases in China. Zhongguo Faxing Qikan. 2019;34:209-220. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Wu D, Zhang Q. Current status and progress in the diagnosis and treatment of coronary heart disease in China. Zhongguo Aizheng Yanjiu Zazhi. 2020;7:159-169. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Di Sciascio G, Patti G, Pasceri V, Gaspardone A, Colonna G, Montinaro A. Efficacy of atorvastatin reload in patients on chronic statin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the ARMYDA-RECAPTURE (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty) Randomized Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:558-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Patti G, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, Mega S, Pasceri V, Briguori C, Colombo A, Yun KH, Jeong MH, Kim JS, Choi D, Bozbas H, Kinoshita M, Fukuda K, Jia XW, Hara H, Cay S, Di Sciascio G. Clinical benefit of statin pretreatment in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a collaborative patient-level meta-analysis of 13 randomized studies. Circulation. 2011;123:1622-1632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Briguori C, Visconti G, Focaccio A, Golia B, Chieffo A, Castelli A, Mussardo M, Montorfano M, Ricciardelli B, Colombo A. Novel approaches for preventing or limiting events (Naples) II trial: impact of a single high loading dose of atorvastatin on periprocedural myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2157-2163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jang Y, Zhu J, Ge J, Kim YJ, Ji C, Lam W. Preloading with atorvastatin before percutaneous coronary intervention in statin-naïve Asian patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: A randomized study. J Cardiol. 2014;63:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zheng B, Jiang J, Liu H, Zhang J, Li H, Su X, Wang H, Song Z, Han Y, Lei H. Efficacy and safety of serial atorvastatin load in Chinese patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the ISCAP (Intensive Statin Therapy for Chinese Patients with Coronary Artery Disease Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;B47-B56. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Naito R, Miyauchi K, Daida H. Racial Differences in the Cholesterol-Lowering Effect of Statin. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:19-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yong H, Wang X, Mi L, Guo L, Gao W, Zhang Y, Cui M. Effects of atorvastatin loading prior to primary percutaneous coronary intervention on endothelial function and inflammatory factors in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7:316-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu Z, Joerg H, Hao H, Xu J, Hu S, Li B, Sang C, Xia J, Chu Y, Xu D. Efficacy of High-Intensity Atorvastatin for Asian Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:725-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jiao Y, Hu F, Zhang Z, Gong K, Sun X, Li A, Liu N. Effect of rosuvastatin dose-loading on serum sLox-1, hs-CRP, and postoperative prognosis in diabetic patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing selected percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:21565-21571. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Jiao Y, Hu F, Zhang Z, Gong K, Sun X, Li A, Liu N. Efficacy and Safety of Loading-Dose Rosuvastatin Therapy in Elderly Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes Undergoing Elective Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35:777-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xie W, Li P, Wang Z, Chen J, Lin Z, Liang X, Mo Y. Rosuvastatin may reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes receiving percutaneous coronary intervention by suppressing miR-155/SHIP-1 signaling pathway. Cardiovasc Ther. 2014;32:276-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Luo J, Li J, Shen X, Hu X, Fang Z, Lv X, Zhou S. The effects and mechanisms of high loading dose rosuvastatin therapy before percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2350-2353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang Z, Dai H, Xing M, Yu Z, Lin X, Wang S, Zhang J, Hou F, Ma Y, Ren Y, Tan K, Wang Y, Ge Z. Effect of a single high loading dose of rosuvastatin on percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2013;18:327-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li Q, Deng SB, Xia S, Du JL, She Q. Impact of intensive statin use on the level of inflammation and platelet activation in stable angina after percutaneous coronary intervention: a clinical study. Med Clin (Barc). 2013;140:532-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gao Y, Jia ZM, Sun YJ, Zhang ZH, Ren LN, Qi GX. Effect of high-dose rosuvastatin loading before percutaneous coronary intervention in female patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125:2250-2254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li W, Fu X, Wang Y, Li X, Yang Z, Wang X, Geng W, Gu X, Hao G, Jiang Y, Fan W, Wu W, Li S. Beneficial effects of high-dose atorvastatin pretreatment on renal function in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiology. 2012;122:195-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yu XL, Zhang HJ, Ren SD, Geng J, Wu TT, Chen WQ, Ji XP, Zhong L, Ge ZM. Effects of loading dose of atorvastatin before percutaneous coronary intervention on periprocedural myocardial injury. Coron Artery Dis. 2011;22:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Guo X. A meta-analysis of sequential therapy of statins on PCI patients in China. Shandong University, 2019. [cited 20 February 2021]. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/kns8/defaultresult/index. |

| 21. | Ye Z, Lu H, Su Q, Guo W, Dai W, Li H, Yang H, Li L. Effect of high-dose rosuvastatin loading before percutaneous coronary intervention in Chinese patients with acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cao A, Qian J, Wang Z. Efficacy of high-dose statins administration before surgery on the reduction of cardiovascular events: A meta analysis. Pharm Care Res. 2018;18:282-287. |

| 23. | Birmingham BK, Bujac SR, Elsby R, Azumaya CT, Zalikowski J, Chen Y, Kim K, Ambrose HJ. Rosuvastatin pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics in Caucasian and Asian subjects residing in the United States. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:329-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lee E, Ryan S, Birmingham B, Zalikowski J, March R, Ambrose H, Moore R, Lee C, Chen Y, Schneck D. Rosuvastatin pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics in white and Asian subjects residing in the same environment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:330-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Birmingham BK, Bujac SR, Elsby R, Azumaya CT, Wei C, Chen Y, Mosqueda-Garcia R, Ambrose HJ. Impact of ABCG2 and SLCO1B1 polymorphisms on pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin, atorvastatin and simvastatin acid in Caucasian and Asian subjects: a class effect? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:341-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tomlinson B, Chan P, Liu ZM. Statin Responses in Chinese Patients. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25:199-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huo Y, Ge JB, Han YL. Expert consensus on intensive statin therapy for patients with acute coronary syndrome. Zhongguo Jieru Xinzangbingxue Zazhi. 2014;22:4-6. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Joint committee issued Chinese guideline for the management of dyslipidemia in adults. Chinese guideline for the management of dyslipidemia in adults. Zhongguo Faxing Qikan. 2016;32:937-953. |

| 29. | Chinese Medical Association in cardiovascular disease branch interventional cardiology group. Chinese Medical Doctor Association cardiovascular physician branch thrombus prevention and control Specialized Committee. Chinese Journal of cardiovascular disease editorial board. Guidelines for percutaneous coronary intervention in China (2016). Zhongguo Xinxueguan Jibing Zazhi. 2016;44:382-400. |

| 30. | Liu H, Dong A, Wang H. Long-term benefits of high-intensity atorvastatin therapy in Chinese acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |