Published online Feb 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1473

Peer-review started: February 3, 2021

First decision: July 16, 2021

Revised: July 22, 2021

Accepted: January 19, 2022

Article in press: January 19, 2022

Published online: February 16, 2022

Processing time: 372 Days and 14.7 Hours

Pain is a common experience for inpatients, and intensive care unit (ICU) patients undergo more pain than other departmental patients, with an incidence of 50% at rest and up to 80% during common care procedures. At present, the management of persistent pain in ICU patients has attracted considerable attention, and there are many related clinical studies and guidelines. However, the management of transient pain caused by certain ICU procedures has not received sufficient attention. We reviewed the different management strategies for procedural pain in the ICU and reached a conclusion. Pain management is a process of continuous quality improvement that requires multidisciplinary team cooperation, pain-related training of all relevant personnel, effective relief of all kinds of pain, and improvement of patients' quality of life. In clinical work, which involves complex and diverse patients, we should pay attention to the following points for procedural pain: (1) Consider not only the patient's persistent pain but also his or her procedural pain; (2) Conduct multimodal pain management; (3) Provide combined sedation on the basis of pain management; and (4) Perform individualized pain management. Until now, the pain management of procedural pain in the ICU has not attracted extensive attention. Therefore, we expect additional studies to solve the existing problems of procedural pain management in the ICU.

Core Tip: In clinical work, which involves complex and diverse patients, we should pay attention to the following points for procedural pain: (1) Consider not only the patient's persistent pain but also his or her procedural pain; (2) Conduct multimodal pain management; (3) Provide combined sedation on the basis of pain management; and (4) Perform individualized pain management.

- Citation: Guo NN, Wang HL, Zhao MY, Li JG, Liu HT, Zhang TX, Zhang XY, Chu YJ, Yu KJ, Wang CS. Management of procedural pain in the intensive care unit. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(5): 1473-1484

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i5/1473.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1473

Pain is a common experience for inpatients, and intensive care unit (ICU) patients undergo more pain than other departmental patients, with an incidence of 50% at rest and up to 80% during common care procedures[1]. The inducing factors of pain in the ICU include primary disease, various monitoring devices, treatment, long-term bed rest, and environmental and psychological factors[2]. In terms of its duration, pain in the ICU is divided into persistent pain (with inducing factors including mechanical ventilation, surgical incision, etc.) and transient pain (with inducing factors including arteriovenous puncture, abdominocentesis, etc.). At present, the management of persistent pain in ICU patients has attracted considerable attention, and there are many related clinical studies[3-5] and guidelines[6,7]. However, the management of transient pain caused by certain ICU procedures has not received sufficient attention. In 2018, although the PADIS guidelines[7] and "The Guidelines for the Management of Pain, Agitation in Adult Patients in the Intensive Care Unit"[2] refer to the prevalence of pain in ICU patients and recommend pain management and sedation to reduce patient discomfort, there are no specific recommendations for managing pain caused by procedures performed in the ICU. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to review the different management strategies for procedural pain in the ICU.

Due to the severity and complexity of diseases in the ICU, various procedures are performed for monitoring, treatment, nursing care and other reasons. According to the procedural purposes, we defined the source of procedural pain into the following four categories: (1) Establishment of vascular access; (2) Noninvasive catheterization of a natural lumen; (3) Percutaneous catheterization and extubation of a natural lumen; and (4) Other procedures (Table 1). Although the above classifications are distinguished for operational purposes, the causes of each type of procedural pain have similar physiological anatomical foundations.

| Category | Specific operation | |||||

| Establishment of vascular access | Arterial puncture and catheterization | Peripherally inserted central catheters | Central venous catheter | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | Continuous renal replacement therapy etc. | |

| Natural cavity noninvasive catheterization | Endotracheal intubation | Bronchofiberscopy | Nasogastric tube intubation | Nasal jejunal intubation | Urethral catheterization etc. | |

| Natural cavity percu | Pericardiocentesis | Thoracentesis | Thoracic closed drainage | Tracheotomy | Abdominocentesis | Extraction of chest tube etc. |

| Others | Turn etc. |

In the past decade, the prevention and treatment concepts of pain, anxiety, and delirium have been updated: treatment based on pain management is emphasized, focusing on early intervention and paying more attention to patient-centered humanistic care while minimizing the side effects of analgesic and sedative drugs[6,8,9]. "The Guidelines for the Management of Pain, Agitation in Adult Patients in the Intensive Care Unit" recommend the preadministration of analgesics or nonpharmacological interventions to relieve pain before procedures that may cause pain[2].

The generation of pain involves both physiological and psychological factors. At present, clinical pain management includes pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments. These drugs include opioid analgesics, nonopioid analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetics. Nonpharmacological pain management, including hypnosis and distraction by virtual reality, has been used as an adjunct for procedural pain management in ICUs. To date, there is not enough evidence to support the value of nonpharmacological pain management in ICUs[10]. Therefore, this review mainly compares the existing pain management approaches from the perspective of drug analgesia according to the different types of procedural pain mentioned above.

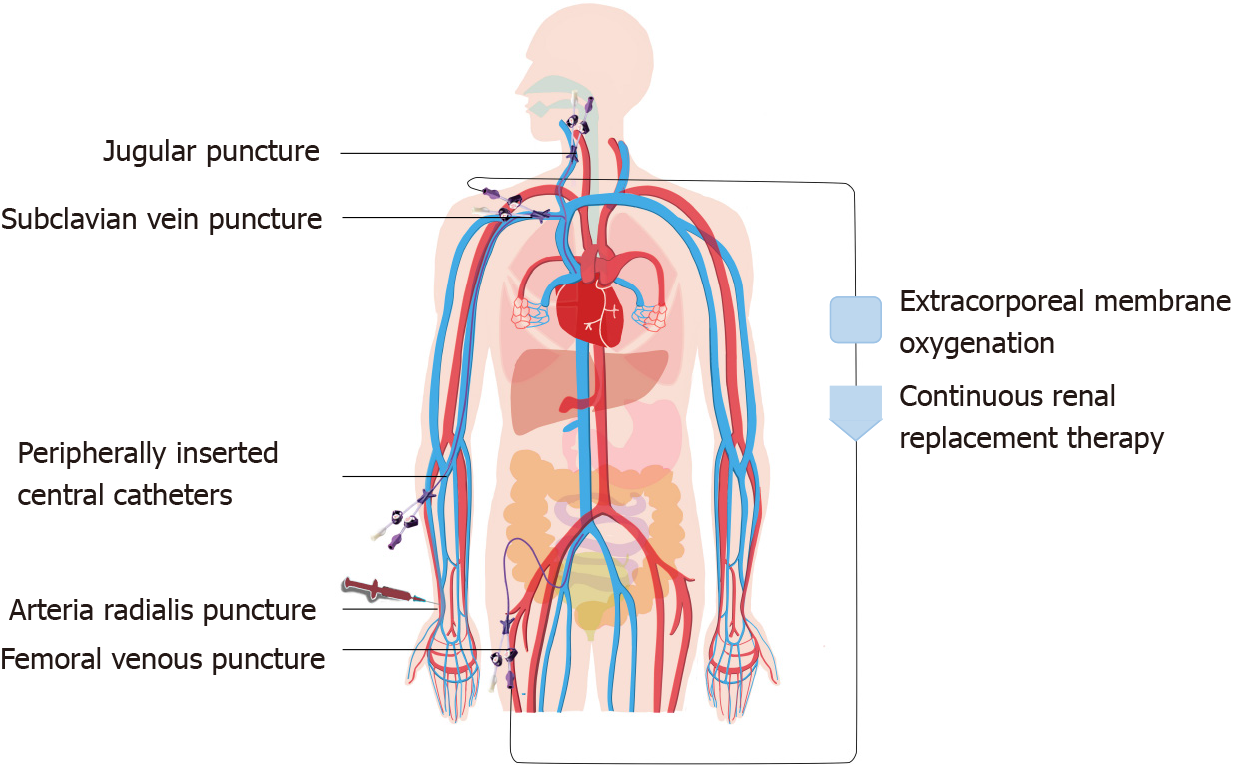

Establishing vascular access is an essential operation in the ICU (Figure 1). For example, arterial puncture and catheterization can enable blood gas analysis and continuous arterial pressure monitoring, and central venous catheters (CVCs) and peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) can facilitate central venous pressure monitoring and the rapid administration of liquid and vasoactive drugs. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) are important organ support methods in the ICU. Both procedures require deep venous catheterization to establish extracorporeal circulation. Improving the patient's oxygenation and excreting metabolic waste from the blood saves valuable time.

At present, pain caused by arterial puncture and catheterization, deep venous catheterization, and PICCs in the ICU is usually managed by local infiltration anesthesia. However, local infiltration anesthesia has the following limitations: (1) Local infiltration anesthesia itself can cause pain; (2) The effect of partial local infiltration anesthesia is not perfect; (3) After local infiltration, superficial arteriovenous structures may be difficult to identify, increasing the difficulty of puncture; and (4) Improper operation of local infiltration anesthesia may cause local anesthetic poisoning. Therefore, some clinical studies have attempted to apply more pain management methods to alleviate the pain caused by the establishment of vascular access.

There are few studies on arterial puncture and catheterization or on PICCs with general anesthesia as pain management methods. Zeng et al[11] found that a subanesthetic dose of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) combined with midazolam (0.05 mg/kg) for arterial puncture has good analgesic and sedative effects, and most patients can awaken within 5 min to 8 min. When adopting this method, local infiltration anesthesia is not needed, and swelling of the puncture site during local anesthesia is avoided, which is beneficial to improving the success rate of puncture. This method has little effect on the patient's breathing and circulation, but for individuals who are elderly and infirm, it is still necessary to pay attention to transient respiratory depression. Because of the side effects of ketamine on pulmonary arterial pressure and intracranial pressure, patients with pulmonary hypertension or intracranial hypertension should be treated with caution[11].

Most studies on the management of pain caused by arterial puncture and catheterization and PICCs focus on topical anesthesia. A review published in 2006 suggested that the use of lidocaine topical anesthesia before arterial puncture can significantly reduce pain and does not affect the success rate of puncture[12]. In 2012, a randomized double-blind trial examined topical anesthesia induced via a lidocaine/tetracaine patch in arterial puncture and showed that both the lidocaine/tetracaine patch and a subcutaneous injection of lidocaine effectively relieved pain during arterial puncture; however, the subcutaneous injection of lidocaine caused discomfort during the injection. In contrast, the lidocaine/tetracaine patch should be placed for 20 min before the operation, and the analgesic effect is better if given enough time[13]. A study published in 2016 compared the analgesic effects of vapocoolant sprays (ethyl chloride and alkane mixtures) with lidocaine local anesthesia during radial artery cannulation. The results showed that vapocoolant sprays can replace local anesthesia with lidocaine to relieve pain and discomfort caused by arterial catheterization[14]. A trial conducted in 2001 evaluated the effectiveness of two types of local anesthesia (buffered lidocaine and EMLA cream, which is a eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine, 2.5% prilocaine, an emulsifier, and a thickener) compared to no anesthesia. The results showed that buffered lidocaine was superior to EMLA cream or no anesthesia in reducing PICC-related pain[15].

Topical anesthesia with different types or formulations of local anesthetics has been used to relieve pain caused by arterial puncture and catheterization and by PICCs in an increasing number of studies. Although topical anesthesia does not cause stabbing pain or local anesthetic poisoning, its anesthetic effect needs to be confirmed by more clinical studies.

A 2014 study by Samantaray and Rao[16] evaluated the efficacy of fentanyl combined with local infiltration anesthesia with lidocaine for CVCs. The results showed that fentanyl is effective in relieving pain and can be safely used in conscious patients. The same team compared the effects of dexmedetomidine, fentanyl, and placebo during CVC placement in a trial conducted in 2016. The study concluded that both dexmedetomidine and fentanyl achieved good analgesia. Dexmedetomidine is superior to fentanyl and placebo in providing comfort to patients but is associated with excessive sedation and cardiovascular adverse events[17]. The latest study conducted in 2019 compared the target-controlled infusion of remifentanil plus local lidocaine infiltration and placebo plus local lidocaine infiltration in conscious patients. Remifentanil is effective in reducing the pain associated with local lidocaine infiltration during CVC placement[18].

The pain management of CVC placement is mostly focused on the intravenous administration of opioid analgesics (remifentanil, fentanyl) combined with lidocaine local infiltration, which can achieve a good analgesic effect while keeping patients awake. Although general anesthesia is more comfortable than local anesthesia, respiratory and circulatory inhibition by general anesthesia cannot be ignored.

The essence of ECMO is an improved artificial heart-lung machine that can be used for both extracorporeal respiratory support and cardiac support. There is currently no independent study on pain management during the establishment of extracorporeal circulation for ECMO. However, some studies have focused on pain management after extracorporeal circulation establishment.

Two recent case studies and one review suggest that ketamine infusion can be used as an analgesic for ECMO patients, reducing sedatives and opioid doses without changing the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) score[19-21]. Based on the above findings, ketamine combined with local lidocaine infiltration may be an option for analgesia in ECMO patients during the establishment of extracorporeal circulation.

There is no independent study on the pain management of extracorporeal circulation establishment before CRRT. Mostly, these cases involve renal insufficiency in patients with CRRT. The choice of pain management should avoid nephrotoxic drugs such as tramadol and NSAIDs and may be patterned after pain management for CVC. The management of pain caused by establishing different types of vascular access is shown in Table 2.

| Operational type | Ref. | Drugs | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Arterial puncture and catheterization | Zeng et al[11], 2007 | Subanesthetic dose of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) combined with midazolam (0.05 mg/kg) | The effect of pain management is 100%, with less side effect on breathing and circulation | Older and infirm should pay attention to transient respiratory depression |

| Rüsch et al[14], 2017 | Vapocoolant sprays | Can replace lidocaine to relieve discomfort caused by arterial catheterization | Not mentioned | |

| Ruetzler et al[13], 2012 | Lidocaine/tetracaine patch | Effectively relieve pain | Need enough time before operation | |

| PICC | Fry and Aholt[15], 2001 | Buffered lidocaine | Effectively relieve pain | With short-term stability |

| CVC | Vardon Bounes et al[18], 2019 | Remifentanil combined with lidocaine | Effectively relieve pain and has a short half-life | Extended operating time |

| Samantaray et al[17], 2016 | Fentanyl | Effectively relieve pain, less adverse respiratory and cardiovascular events | It is not as good as dexmedetomidine in providing comfort to patients | |

| Samantaray and Rao[16], 2014 | Fentanyl | Effectively relieve pain | Respiratory depression may occur | |

| ECMO | Maybauer et al[21], 2019 | Ketamine | Provides relatively stable hemodynamic stability while maintaining airway reflex | There may be dose-related hallucinations, paralysis, tearing, tachycardia, and possibly increased intracranial pressure, and coronary ischemia |

| Floroff et al[20], 2016 | Ketamine | Less respiratory depression, better pain control, boosting, and increased cardiac output | There may be dose-related hallucinations, sputum, hooliganism | |

| Tellor et al[19], 2015 | Ketamine | Can reduce the amount of opioids used in surgical patients | The safety and efficacy of patients requiring ECMO therapy have not been determined |

In addition to the management of procedural pain caused by the establishment of vascular access, we should also pay attention to improving the success rate of vascular access and avoiding repeated procedures that cause patients more pain. A large number of studies have confirmed that ultrasound guidance in arterial puncture, PICCs and CVCs can not only improve the success rate of puncture but also reduce the incidence of adverse events and improve the satisfaction and comfort of patients[22,23]. Moreover, bedside ultrasound can also identify malpositioning of the CVC and pneumothorax faster than an X-ray examination[24,25].

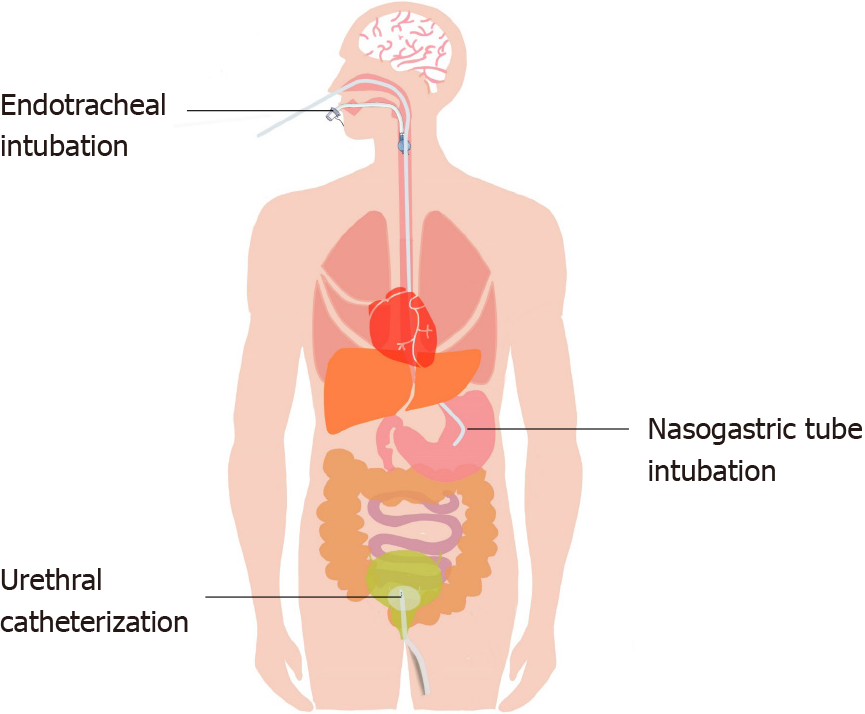

Natural cavities are channels that connect the inside and outside of the human body, and they are sensitive and highly reactive. When a fiberoptic bronchoscope, stomach tube or urinary catheter enters a natural cavity, the device stimulates the mucous membrane, causing discomfort or even pain (Figure 2). Therefore, proper pain management combined with sedation can not only relieve the patient's discomfort and pain but also improve the success rate of intubation and avoid additional pain caused by repeated operations.

A 2013 study found that remifentanil target-controlled infusion analgesia was reliable in ICU patients who required bronchoscopy with spontaneous breathing[26].

Kundra et al[27] evaluated the efficacy of upper airway anesthesia produced by nebulized lidocaine against a combined regional block (CRB) for awake fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation. The results showed that both nebulization and CRB produced satisfactory anesthesia of the upper airway, but CRB provided better patient comfort and hemodynamic stability[27]. A randomized controlled study was performed to compare two methods of airway anesthesia, namely, ultrasonic nebulization of a local anesthetic and the performance of airway blocks. The results showed that upper airway blocks provided better quality anesthesia than lidocaine nebulization[28].

The above studies indicate that the analgesic effect of topical anesthesia combined with a nerve block is superior, but it may be difficult for some clinicians to achieve. On the basis of adequate topical anesthesia, combining intravenous analgesic sedative drugs may have a better effect, but this option needs to be confirmed by clinical research.

Nasal tube intubation is a common operation in the ICU but a painful process for patients[29]. Pain management for nasal tube intubation mainly involves topical anesthesia.

A randomized controlled trial by Singer and Konia[30] showed that using topical lidocaine and phenylephrine for the nose and tetracaine with benzocaine spray for the throat prior to nasogastric (NG) intubation resulted in significantly less pain and discomfort than using a nasal surgical lubricant alone. Widespread use of topical anesthetics and vasoconstrictors prior to NG intubation is recommended[30]. Studies by Wolfe et al[31] have shown that atomized nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal 4% lidocaine results in clinically and statistically significant reductions in pain during NG tube (NGT) placement. Ducharme and Matheson[32] compared atomized lidocaine, atomized cocaine, and lidocaine gel and found that 2% lidocaine gel appeared to provide the best option for a topical anesthetic during NGT insertion. A randomized controlled trial by Cullen et al[33] showed that nebulized lidocaine decreases the discomfort of NGT insertion and should be considered before passing an NGT.

Both nebulized and topical local anesthetics (lidocaine, tetracaine, cocaine) can alleviate the pain of NG intubation. The combined application of both nebulized and topical local anesthetics may be a better option during NG intubation.

There is little research on analgesia after nasal jejunal intubation. In fact, management for nasal jejunal intubation may be patterned after pain management for NG tube intubation.

A randomized controlled trial in 2004 determined whether pretreatment of the urethra with topical lidocaine reduces the pain associated with urethral catheterization. The results showed that using a topical lidocaine gel can reduce the pain associated with male urethral catheterization in comparison with topical lubricants only[34]. Another randomized controlled trial in 2007 compared the effects of a lidocaine gel and a water-based lubricating gel for female urethral catheterization. The results showed that compared with the water-based lubricating gel, the lidocaine gel substantially reduced the procedural pain caused by female urethral catheterization[35].

All of the above studies have shown that topical anesthesia with a lidocaine gel can effectively reduce the pain experienced during urethral catheterization. The management of pain caused by natural cavity noninvasive catheterization is shown in Table 3.

| Operational type | Ref. | Drugs | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Fiberbronchoscopy | Chalumeau-Lemoine et al[26], 2013 | Remifentanil | Shorten the operational time, reduce discomfort, and have better antitussive effect | May cause respiratory arrest |

| Gupta et al[28], 2014 | 2% lignocaine and viscous lignocaine gargles | Effectively relieve pain and provide comfort | Not mentioned | |

| Kundra et al[27], 2000 | Translaryngeal block, bilateral superior laryngeal nerve block and three 4% lignocaine-soaked cotton swabs in the nose (CRB group) | Provided better patient comfort and haemodynamic stability | Not mentioned | |

| Nasogastric tube intubation | Cullen et al[33], 2004 | Nebulized lidocaine | Can significantly alleviate pain | Can cause complications such as nosebleeds |

| Ducharme and Matheson[32], 2003 | 2% lidocaine gel | Effectively alleviate pain and is easy to use | Not mentioned | |

| Wolfe et al[31], 2000 | 4% Nebulized lidocaine | Significantly alleviate pain | Not mentioned | |

| Singer and Konia[30], 1999 | Lidocaine, tetracaine | Alleviate pain | Adverse events such as vomiting and nosebleeds | |

| Urethral catheterization | Chung et al[35], 2007 | Lidocaine gel | Alleviate pain | Not mentioned |

| Siderias et al[34], 2004 | Lidocaine gel | Alleviate pain | Not mentioned |

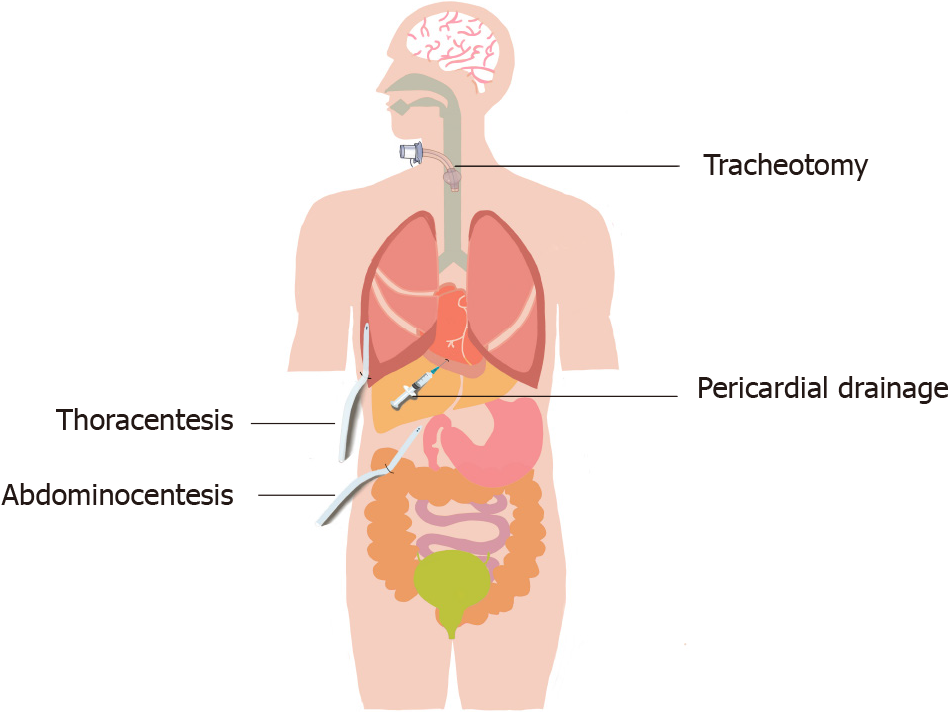

Natural cavity percutaneous catheterization is common in the ICU (Figure 3). Tracheotomy can quickly establish a respiratory passage and save patients' lives; thoracentesis, thoracic closed drainage, pericardial drainage, and abdominocentesis can drain effusions or gas to relieve symptoms and to diagnose and treat diseases. Since these operations require puncture through the skin and muscle layers, pain management is necessary.

Mechanical ventilation is an important means of respiratory support for critically ill patients. The clinical application guidelines for mechanical ventilation clearly suggest that patients who cannot have their artificial airways removed in the short term should be selected for replacement with tracheotomy as soon as possible[36]. A 2010 study showed that compared with tracheal intubation, tracheotomy may increase survival rates in mechanical ventilation patients. However, during tracheotomy, some patients are conscious and experience a certain fear of the procedure. Therefore, appropriate preoperative pain management and sedation are inevitable[37].

A 2011 trial compared local anesthesia (2% lidocaine tracheal mucosal-surface anesthesia and local-infiltration anesthesia) and monitored anesthesia (midazolam, propofol and fentanyl given intravenously after surface and local anesthesia) during tracheotomy. Monitored anesthesia gave patients a higher level of comfort, no memory of the tracheotomy and more stable hemodynamics[38]. A recent study evaluated the pain management and side effects of remifentanil in percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy. The results showed that based on propofol general anesthesia, combined treatment with remifentanil and lidocaine for local anesthesia can result in a shorter recovery time and more tolerable pain after recovery[39].

Tracheotomy pain management has mostly focused on intravenous analgesia (fentanyl, remifentanil), sedative drugs (propofol, midazolam) and combination treatment with local infiltration anesthesia (lidocaine), which can provide good pain management and sedative effects. According to the patient's circulatory state and the original pain management sedation plan, the pain management sedation combination and the local infiltration anesthesia method can be selected.

A 2004 study compared morphine and ketorolac in cardiac surgery patients undergoing chest tube removal. The findings confirmed that if used correctly, either an opioid (morphine) or an NSAID (ketorolac) can substantially reduce pain during chest tube removal without causing adverse sedative effects[40]. However, a review published in 2005 suggested that morphine alone does not provide satisfactory pain management for chest tube removal pain. NSAIDs, local anesthetics and inhalation agents may play a role in providing more effective analgesia[41].

A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in 2005 evaluated the efficacy of topical valdecoxib as an analgesic during chest tube removal in postcardiac surgical patients. The results showed that compared with liquid paraffin, valdecoxib is a safe and effective topical analgesic[42].

In addition, three studies compared whether the preuse of ice packs can alleviate the pain of chest tube removal. Integration of the three studies in a meta-analysis showed that the preuse of ice packs can alleviate the pain of patients with chest tubes. The pain score was reduced after removal of the chest tube, SMD=0.30, [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.01-0.59, P = 0.04, I2 = 0%][43-45].

There are many pain management methods, such as intravenous opioid analgesics, NSAIDs and cold compresses, for the extraction of chest tubes. There are few studies on local infiltration anesthesia, but it may be a better pain management method for the extraction of chest tubes because local infiltration anesthesia not only reduces pain during extubation but also reduces pain after extubation. The effect of local infiltration anesthesia in the extraction of chest tubes needs to be confirmed by clinical studies.

There are few pain management studies on thoracentesis and abdominocentesis. The traditional pain management method is local lidocaine infiltration anesthesia, which can provide effective analgesic effects. However, short-term pain management and sedation combined with local infiltration anesthesia may be a better choice, and we expect more clinical studies to confirm this option. The management of pain caused by natural cavity percutaneous catheterization and extubation is shown in Table 4.

| Operational type | Ref. | Drugs/physical method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Tracheotomy | Chang[39], 2017 | Remifentanil and lidocaine combined with propofol | Can result in a shorter recovery time and more pain tolerable after recovery | Inhibition of heart and breathing |

| Dong et al[38], 2011 | Monitored anesthesia care | Give patients a higher level of comfort, no memory for tracheotomy and the hemodynamics is more stable | Intravenous administration to patients with difficulty in ventilation or intubation should be cautious | |

| Extraction of chest tube | Puntillo and Ley[40], 2004 | Morphine and ketorolac | Alleviate pain | Morphine may cause sedation |

| Singh and Gopinath[42], 2005 | Valdecoxib | Can alleviate pain safely and effectively | Can't completely alleviate pain | |

| Gorji et al[43], 2014 | Ice packs | Effectively alleviate pain | Not mentioned |

Some nursing care in the ICU can also cause discomfort to the patient, and appropriate pain management can reduce the incidence of pain and adverse events.

Turning is part of routine nursing care that is beneficial to sputum discharge and can even prevent hemorrhoids. However, due to the patient's own disease and the presence of various tubes, the patient may suffer from pulling and friction pain during turning. Even if the movement is slow and gentle, it will cause discomfort and pain to the patient.

In a randomized controlled trial conducted by Robleda et al[46], patients who underwent mechanical ventilation in the ICU were randomized to a fentanyl group (39 patients) and a placebo group (36 patients). Fentanyl or placebo was administered before turning. The incidence of pain in the fentanyl group was lower than that in the control group, and the incidence of adverse events was not statistically significant in the fentanyl group[46].

A prospective intervention study by de Jong et al[47] found that planned analgesia treatment (analgesic drugs combined with music) before turning can reduce the incidence of severe pain from 16% to 6% (odds ratio = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.11-0.98, P = 0.04) and the incidence of serious adverse events from 37% to 17%.

At present, no more attention is being paid to pain management during patient turning. Because the pain caused by turning is mostly systemic, general anesthesia may be a good choice. Remifentanil can be chosen because it has a quick effect and a short half-life; moreover, its analgesic effect and side effects are dose-dependent, so it is suitable for turning. The management of pain caused by other procedures is shown in Table 5.

| Operational type | Ref. | Drugs/physical method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Turn | Robleda et al[46], 2016 | Fentanyl | Effectively alleviate pain | Non-tracheal intubation patients use caution and may cause respiratory depression or apnea |

| de Jong et al[47], 2013 | Analgesic drug combined music | Effectively alleviate pain | The feasibility and impact of large-scale routine implementation has not been evaluated |

Since some ICU patients are already in a state of analgesia and sedation during the above operations, the combination of local anesthesia (surface anesthesia or local infiltration anesthesia) on the basis of deepening their analgesia and sedation may be a more effective pain management method for procedural pain. However, for patients who are not under analgesic sedation, the pain management methods mentioned above can be referred to.

Critical care medicine aims to provide the most comprehensive and effective life support for patients with multiple organ dysfunction and severe nonterminal diseases to save their lives, improve their prognosis to the greatest extent and increase their quality of life. Contemporary medicine focuses on human care. Pain management in the ICU can eliminate or alleviate pain and discomfort, reduce adverse stimuli and excessive sympathetic nervous system excitement, facilitate and improve sleep, induce procedural amnesia, reduce memory in the ICU, alleviate or reduce anxiety, incite or even paralyze, prevent unconscious movements, reduce the metabolic rate and decrease oxygen consumption to ensure organ metabolism.

Pain management is a process of continuous quality improvement that requires multidisciplinary team cooperation, pain-related training of all relevant personnel, effective relief of all kinds of pain, and improvement of patients' quality of life. In clinical work, which involves complex and diverse patients, we should pay attention to the following points for procedural pain: (1) Consider not only the patient's persistent pain but also his or her procedural pain; (2) Conduct multimodal pain management; (3) Provide combined sedation on the basis of pain management; and (4) Perform individualized pain management. Until now, the pain management of procedural pain in the ICU has not attracted extensive attention. There are few studies and there is no clear standard for the application of drugs; thus, there is no adequate guidance for clinicians to use exact treatment methods to reduce patients' pain and improve their prognosis. Moreover, for some special procedures, such as ECMO and CRRT, we should provide individualized pain management based on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Therefore, we expect additional studies to solve the existing problems of procedural pain management in the ICU.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ewers A S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gao CC

| 1. | Skrobik Y, Chanques G. The pain, agitation, and delirium practice guidelines for adult critically ill patients: a post-publication perspective. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chinese Medical Association Critical Care Medicine Branch. The Guidelines for the Management of Pain, Agitation in Adult Patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Zhonghua Zhongzheng Yixue Dianzi Zazhi. 2018;4:90-113. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Garber PM, Droege CA, Carter KE, Harger NJ, Mueller EW. Continuous Infusion Ketamine for Adjunctive Analgosedation in Mechanically Ventilated, Critically Ill Patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39:288-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhu Y, Wang Y, Du B, Xi X. Could remifentanil reduce duration of mechanical ventilation in comparison with other opioids for mechanically ventilated patients? Crit Care. 2017;21:206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhao H, Yang S, Wang H, Zhang H, An Y. Non-opioid analgesics as adjuvants to opioid for pain management in adult patients in the ICU: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2019;54:136-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gélinas C, Dasta JF, Davidson JE, Devlin JW, Kress JP, Joffe AM, Coursin DB, Herr DL, Tung A, Robinson BR, Fontaine DK, Ramsay MA, Riker RR, Sessler CN, Pun B, Skrobik Y, Jaeschke R; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:263-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2333] [Cited by in RCA: 2401] [Article Influence: 200.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, Watson PL, Weinhouse GL, Nunnally ME, Rochwerg B, Balas MC, van den Boogaard M, Bosma KJ, Brummel NE, Chanques G, Denehy L, Drouot X, Fraser GL, Harris JE, Joffe AM, Kho ME, Kress JP, Lanphere JA, McKinley S, Neufeld KJ, Pisani MA, Payen JF, Pun BT, Puntillo KA, Riker RR, Robinson BRH, Shehabi Y, Szumita PM, Winkelman C, Centofanti JE, Price C, Nikayin S, Misak CJ, Flood PD, Kiedrowski K, Alhazzani W. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e825-e873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1292] [Cited by in RCA: 2131] [Article Influence: 355.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Balas M, Buckingham R, Braley T, Saldi S, Vasilevskis EE. Extending the ABCDE bundle to the post-intensive care unit setting. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013;39:39-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vincent JL, Shehabi Y, Walsh TS, Pandharipande PP, Ball JA, Spronk P, Longrois D, Strøm T, Conti G, Funk GC, Badenes R, Mantz J, Spies C, Takala J. Comfort and patient-centred care without excessive sedation: the eCASH concept. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:962-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | He ZH, Yang CL. Pain assessment and treatment progress in critically ill patients in ICU. Jiangxi Yixue Zazhi. 2011;46:290-293. |

| 11. | Zeng J, Wu JL, Ma L. Application of subanesthetic dose of ketamine combined with midazolam during arterial puncture. Guangxi Yixue Zazhi. 2007;29:1001-1002. |

| 12. | Hudson TL, Dukes SF, Reilly K. Use of local anesthesia for arterial punctures. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:595-599. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ruetzler K, Sima B, Mayer L, Golescu A, Dunkler D, Jaeger W, Hoeferl M, You J, Sessler DI, Grubhofer G, Hutschala D. Lidocaine/tetracaine patch (Rapydan) for topical anaesthesia before arterial access: a double-blind, randomized trial. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:790-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rüsch D, Koch T, Seel F, Eberhart L. Vapocoolant Spray Versus Lidocaine Infiltration for Radial Artery Cannulation: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31:77-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fry C, Aholt D. Local anesthesia prior to the insertion of peripherally inserted central catheters. J Infus Nurs. 2001;24:404-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Samantaray A, Rao MH. Effects of fentanyl on procedural pain and discomfort associated with central venous catheter insertion: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:421-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Samantaray A, Hanumantha Rao M, Sahu CR. Additional Analgesia for Central Venous Catheter Insertion: A Placebo Controlled Randomized Trial of Dexmedetomidine and Fentanyl. Crit Care Res Pract. 2016;2016:9062658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vardon Bounes F, Pichon X, Ducos G, Ruiz J, Samier C, Silva S, Sommet A, Fourcade O, Conil JM, Minville V. Remifentanil for Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in Central Venous Catheter Insertion: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin J Pain. 2019;35:691-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tellor B, Shin N, Graetz TJ, Avidan MS. Ketamine infusion for patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: a case series. F1000Res. 2015;4:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Floroff CK, Hassig TB, Cochran JB, Mazur JE. High-Dose Sedation and Analgesia During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Focus on the Adjunctive Use of Ketamine. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2016;30:36-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Maybauer MO, Koerner MM, Maybauer DM. Perspectives on adjunctive use of ketamine for analgosedation during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15:349-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang Q, Wang N, Sun Y. Clinical effect of peripherally inserted central catheters based on modified seldinger technique under guidance of vascular ultrasound. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32:1179-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim YO, Chung CR, Gil E, Park CM, Suh GY, Ryu JA. Safety and feasibility of ultrasound-guided placement of peripherally inserted central catheter performed by neurointensivist in neurosurgery intensive care unit. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bou Chebl R, Kiblawi S, El Khuri C, El Hajj N, Bachir R, Aoun R, Abou Dagher G. Use of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound for Confirmation of Central Venous Catheter Placement: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:2503-2510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ablordeppey EA, Drewry AM, Beyer AB, Theodoro DL, Fowler SA, Fuller BM, Carpenter CR. Diagnostic Accuracy of Central Venous Catheter Confirmation by Bedside Ultrasound Versus Chest Radiography in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:715-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chalumeau-Lemoine L, Stoclin A, Billard V, Laplanche A, Raynard B, Blot F. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy and remifentanil target-controlled infusion in ICU: a preliminary study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kundra P, Kutralam S, Ravishankar M. Local anaesthesia for awake fibreoptic nasotracheal intubation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:511-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gupta B, Kohli S, Farooque K, Jalwal G, Gupta D, Sinha S, Chandralekha. Topical airway anesthesia for awake fiberoptic intubation: Comparison between airway nerve blocks and nebulized lignocaine by ultrasonic nebulizer. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8:S15-S19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Singer AJ, Richman PB, Kowalska A, Thode HC Jr. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:652-658. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Singer AJ, Konia N. Comparison of topical anesthetics and vasoconstrictors vs lubricants prior to nasogastric intubation: a randomized, controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:184-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wolfe TR, Fosnocht DE, Linscott MS. Atomized lidocaine as topical anesthesia for nasogastric tube placement: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:421-425. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Ducharme J, Matheson K. What is the best topical anesthetic for nasogastric insertion? J Emerg Nurs. 2003;29:427-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cullen L, Taylor D, Taylor S, Chu K. Nebulized lidocaine decreases the discomfort of nasogastric tube insertion: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:131-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Siderias J, Gaudio F, Singer AJ. Comparison of topical anesthetics and lubricants prior to urethral catheterization in males: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:703-706. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Chung C, Chu M, Paoloni R, O'Brien MJ, Demel T. Comparison of lignocaine and water-based lubricating gels for female urethral catheterization: a randomized controlled trial. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:315-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chinese Medical Association Critical Care Medicine Branch. Clinical Application Guidelines for Mechanical Ventilation (2006). Zhongguo Jijiu Yixue. 2007;19. |

| 37. | Wu YK, Tsai YH, Lan CC, Huang CY, Lee CH, Kao KC, Fu JY. Prolonged mechanical ventilation in a respiratory-care setting: a comparison of outcome between tracheostomized and translaryngeal intubated patients. Crit Care. 2010;14:R26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Dong YC, Su RX, Wu WM, Li G. Clinical application of monitoring anesthesia management in percutaneous dilatation tracheotomy. Huaxi Kouqiang Yixue Zazhi. 2011;29:626-628. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Chang SY. Analgesic study of remifentanil in short operation of ICU. M.D. Thesis, Zhengzhou University. 2017. Available from: https://t.cnki.net/kcms/detail?v=i8RQNj_vMVRYPe5jP8kzRPhbPTZW21wxREglgzGTPk_VKNcaBqGeQX-0c1pzIg3u87glUmwYzKtHLLjT2PCoEPL5Xc0eIfu0Wpz4xUcUULjDUYxJQkwpG1m4EBAVuvYF&uniplatform=NZKPT. |

| 40. | Puntillo K, Ley SJ. Appropriately timed analgesics control pain due to chest tube removal. Am J Crit Care. 2004;13:292-301; discussion 302; quiz 303. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Bruce EA, Howard RF, Franck LS. Chest drain removal pain and its management: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:145-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Singh M, Gopinath R. Topical analgesia for chest tube removal in cardiac patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;19:719-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gorji HM, Nesami BM, Ayyasi M, Ghafari R, Yazdani J. Comparison of Ice Packs Application and Relaxation Therapy in Pain Reduction during Chest Tube Removal Following Cardiac Surgery. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Sauls J. The use of ice for pain associated with chest tube removal. Pain Manag Nurs. 2002;3:44-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Demir Y, Khorshid L. The effect of cold application in combination with standard analgesic administration on pain and anxiety during chest tube removal: a single-blinded, randomized, double-controlled study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2010;11:186-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Robleda G, Roche-Campo F, Sendra MÀ, Navarro M, Castillo A, Rodríguez-Arias A, Juanes-Borrego E, Gich I, Urrutia G, Nicolás-Arfelis JM, Puntillo K, Mancebo J, Baños JE. Fentanyl as pre-emptive treatment of pain associated with turning mechanically ventilated patients: a randomized controlled feasibility study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:183-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | de Jong A, Molinari N, de Lattre S, Gniadek C, Carr J, Conseil M, Susbielles MP, Jung B, Jaber S, Chanques G. Decreasing severe pain and serious adverse events while moving intensive care unit patients: a prospective interventional study (the NURSE-DO project). Crit Care. 2013;17:R74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |