Published online Feb 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1333

Peer-review started: August 17, 2021

First decision: November 2, 2021

Revised: November 17, 2021

Accepted: January 22, 2021

Article in press: December 22, 2021

Published online: February 6, 2022

Processing time: 159 Days and 8.6 Hours

Single atrium with single ventricle, or a two-chambered heart, is an extremely rare congenital malformation. Few cases with two-chambered heart surviving to adulthood have been reported.

We reported an adult female patient with a two-chambered heart and situs inversus totalis accompanied by multiple pregnancies and abortions. Magnetic resonance imaging detected a two-chambered heart. B-ultrasound-guided uterine aspiration was performed to absorb 8 g and 10 g of organized villus and decidual tissues, respectively, with a small amount of bleeding. Postoperatively, cyanosis and fatigue-induced shortness of breath were gradually relieved. The patient has currently outlived all similar cases reported so far.

Hemodynamic changes in pregnant women with two-chambered heart impaired cardiac function, responsible for hypoperfusion and miscarriage.

Core tip: The two-chambered heart is characterized by common atrioventricular valves connecting the single atrium and single ventricle. Most patients with two-chambered heart die before or around 20 years of age. Pregnancy in these patients is very rare, and it is unknown how the disease might affect the pregnancy outcome. The current patient with a two-chambered heart has lived longer than all similar cases reported to date, and has remained active. The case reported here was accompanied by eight adverse pregnancies and early abortions. Pregnancy may negatively affect cardiac function in patients with a two-chambered heart, and poor heart function could lead to uterine hypoperfusion and subsequent miscarriage.

- Citation: Duan HZ, Liu JJ, Zhang XJ, Zhang J, Yu AY. Multiple miscarriages in a female patient with two-chambered heart and situs inversus totalis: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(4): 1333-1340

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i4/1333.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1333

Single ventricle occurs in 0.5–1/100000 live births, accounting for 1%–2% of all cases with neonatal congenital heart diseases[1]. Single ventricle with single atrium, or the two-chambered heart, is clinically rarer and associated with worse prognosis, with the patients often dying several months after birth and rarely surviving to adulthood[2]. Fewer than 10 cases with two-chambered heart surviving to adulthood have been reported worldwide[3-7], including a Japanese patient who has survived the longest (42 years). The two-chambered heart is characterized by a single atrium and a single ventricle connected by a common atrioventricular valve. Since most patients carrying this heart defect die before or around the age of 20 years[3-6], pregnancy in these patients is very rare, and how this disease affects the pregnancy outcome is rarely described. Here, we report a case of two-chambered dextrocardia and multiple miscarriages.

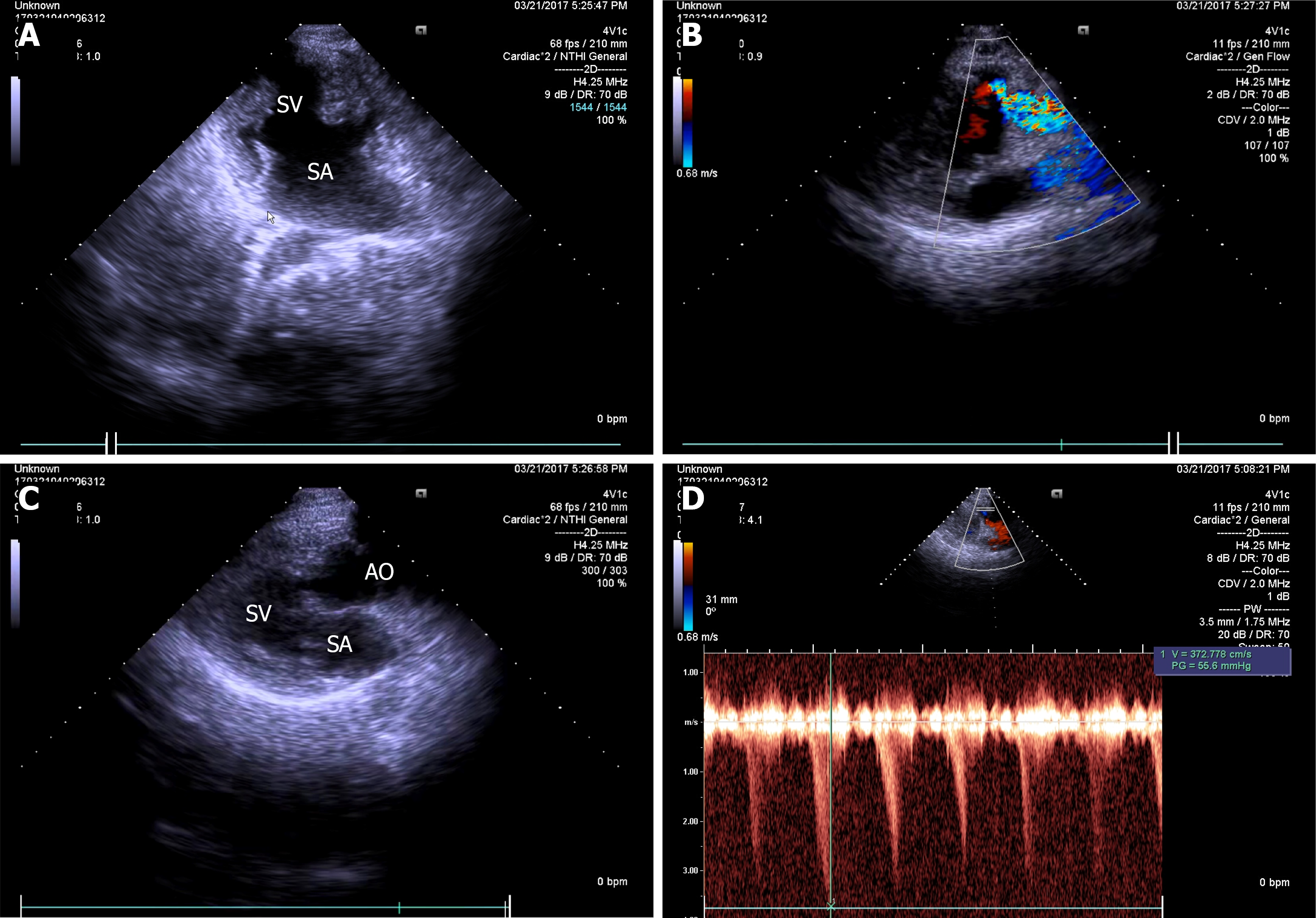

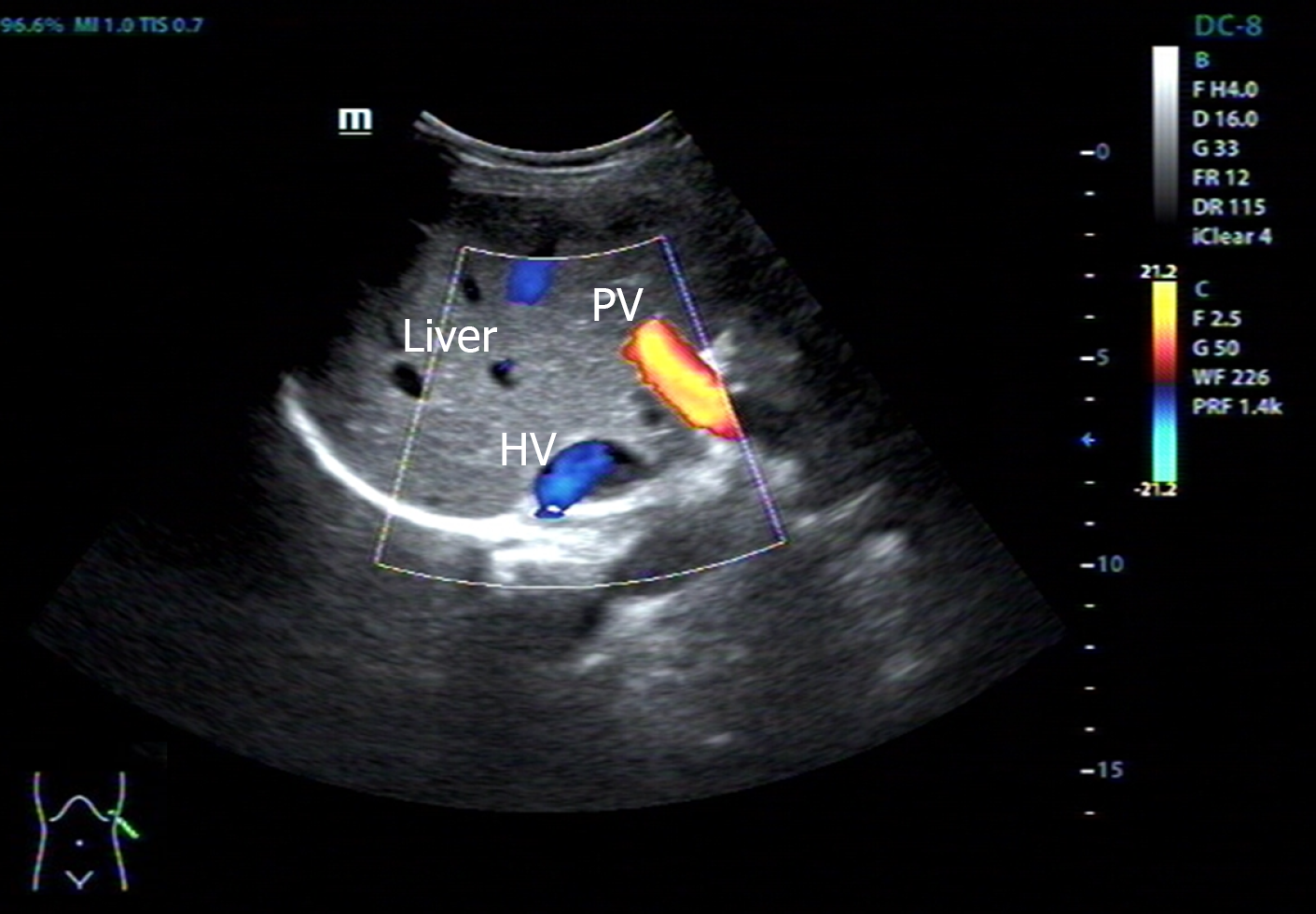

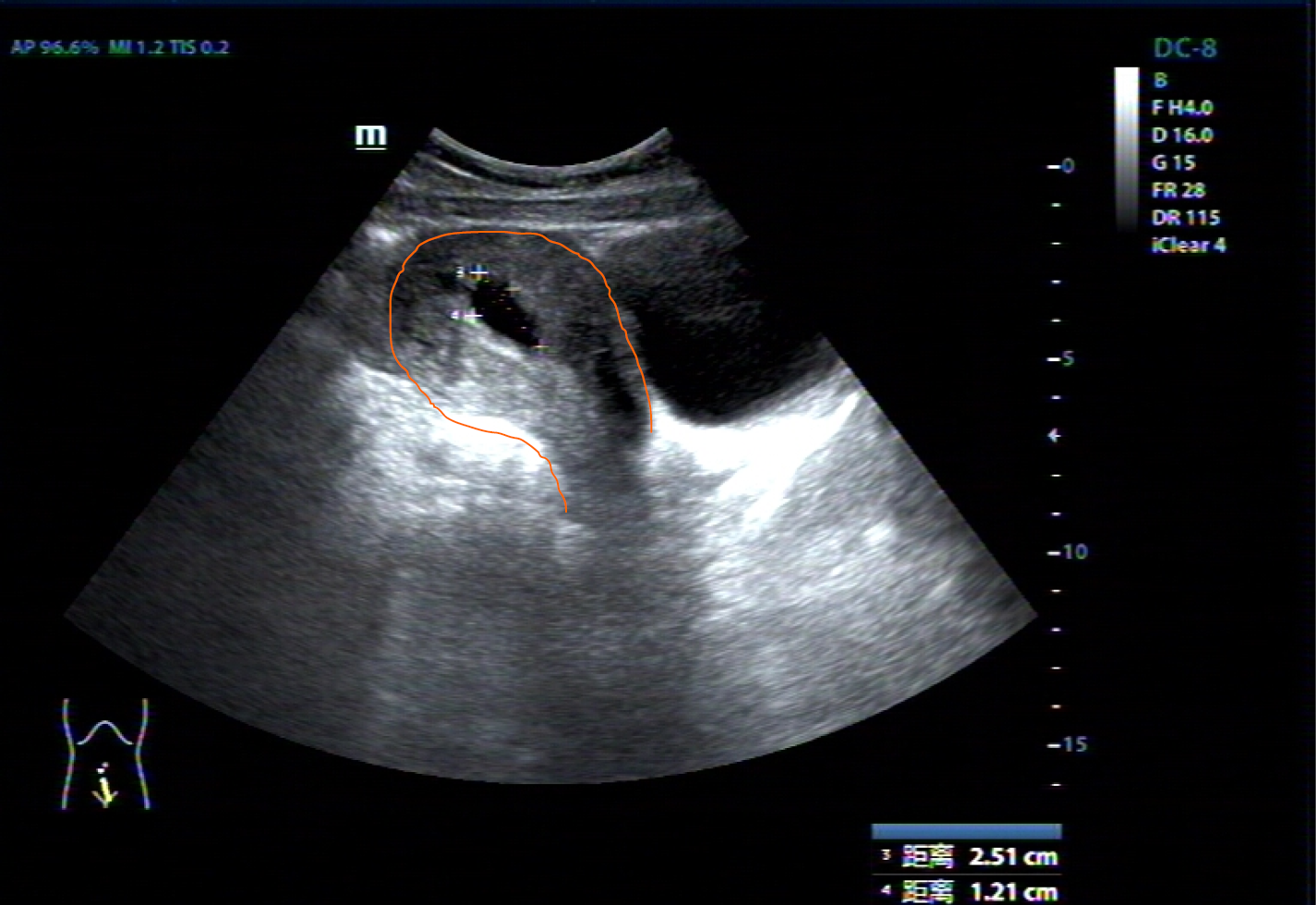

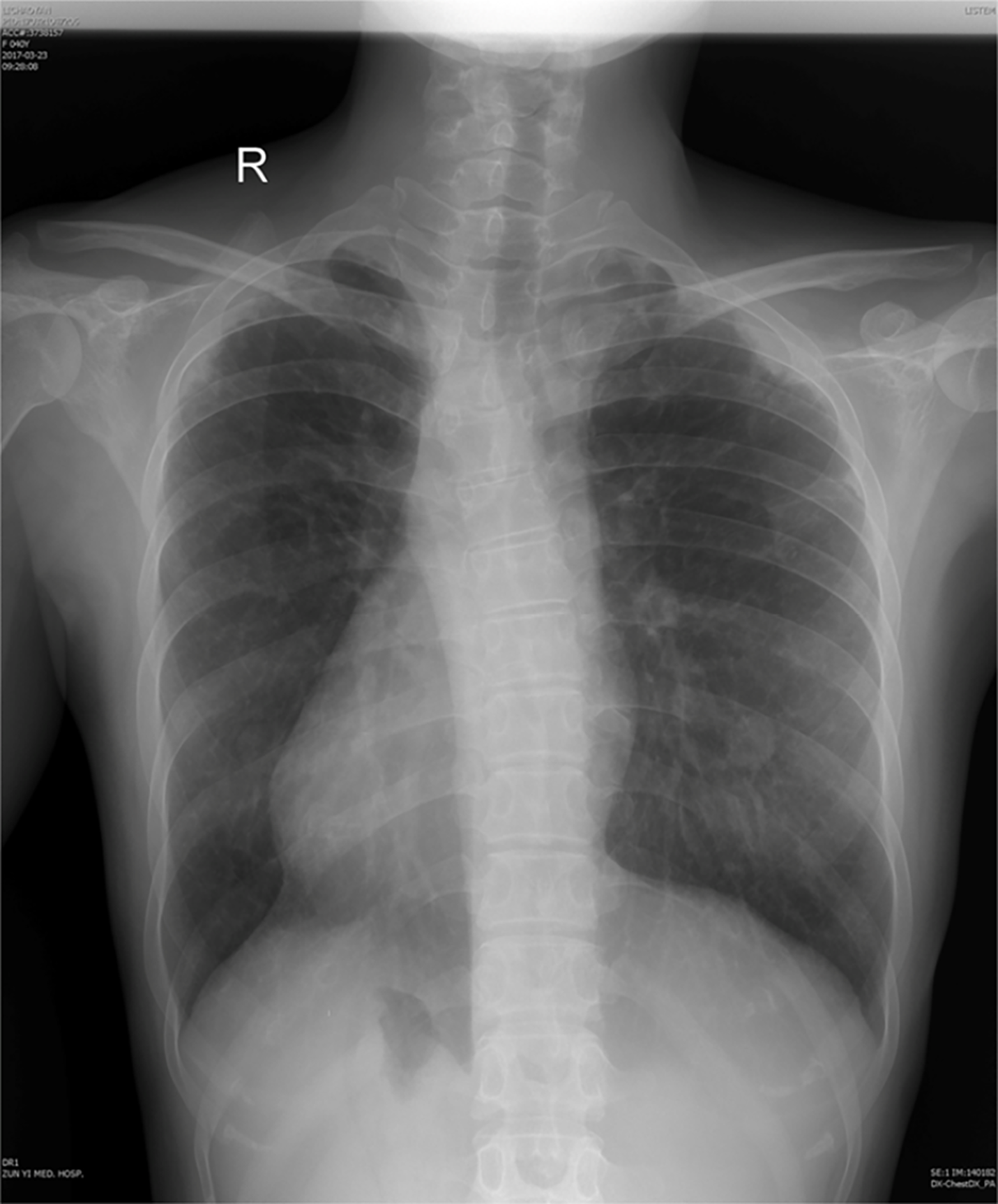

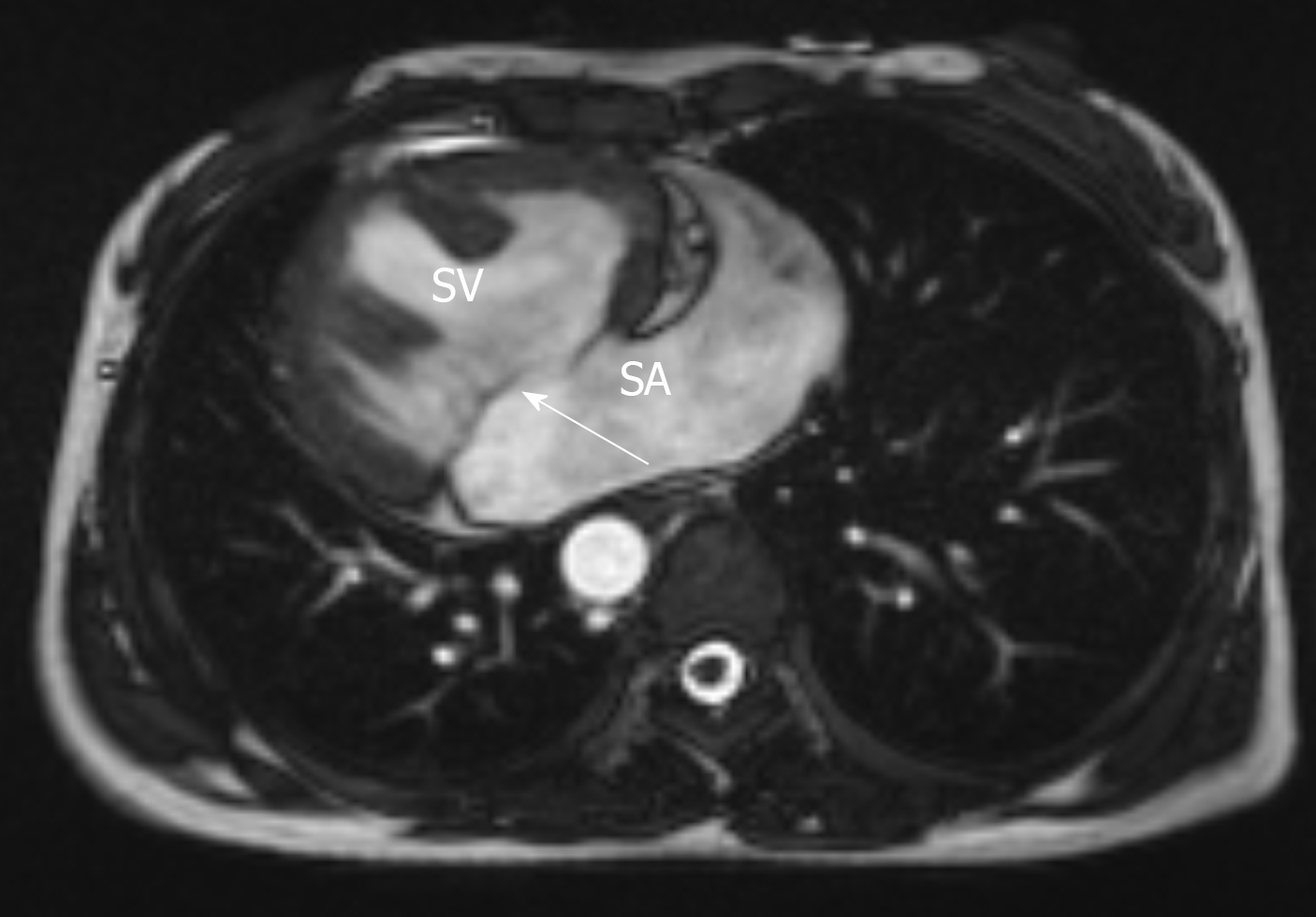

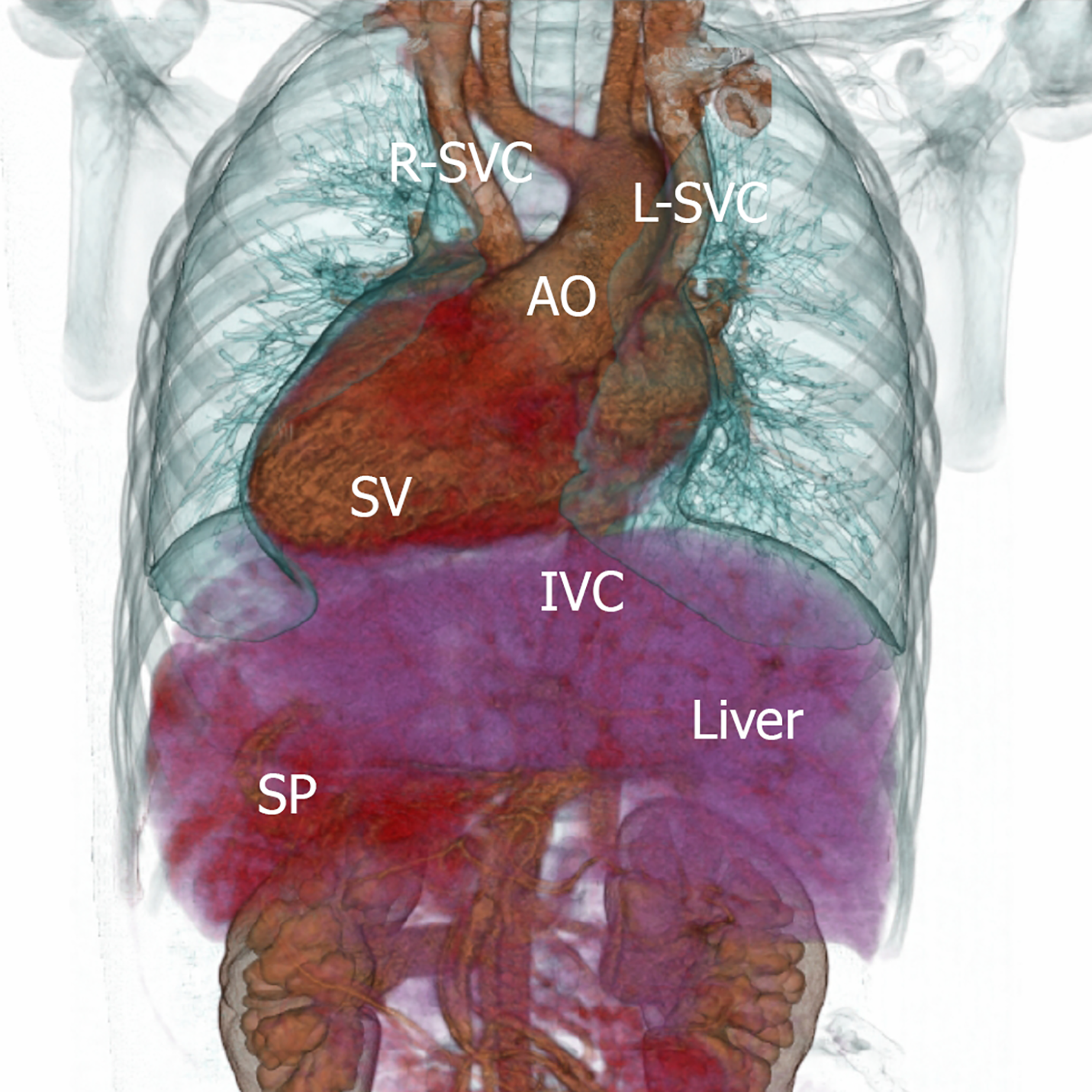

Cardiac color doppler ultrasound (Figure 1) revealed single ventricle dextrocardia (57 mm × 50 mm), anatomical left ventricular morphology, and small stumps only in the ventricular septum; single atrium (67 mm × 41 mm); aorta located on the left posterior side, and pulmonary artery on the right front side, both originating from the main ventricle cavity; pulmonary valve thickening and adhesion, with limited opening; main pulmonary artery diameter of 14 mm; ill-defined left and right pulmonary arteries; aorta diameter of 36 mm; and right-sided aortic arch with right-sided descending aorta. Abdominal B-ultrasound (Figure 2) showed situs inversus totalis. The liver and spleen were on the left and right sides, respectively. Electrocardiography revealed dextrocardia, sinus tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy. Abdominal B-ultrasound (Figure 3) showed an anteverted uterus, with a volume of about 72 mm × 65 mm × 50 mm. A liquid dark area with a volume of 21 mm × 27 mm × 9.8 mm was visible in the uterine cavity, with no obvious yolk sac and embryo echo observed. The left ovary (2.8 cm × 1.7 cm × 1.5 cm) was located in front of the left side of the uterine floor. The right ovary (3.2 cm × 2.1 cm × 1.6 cm) was located on the upper right side of the uterine floor. In addition, X-ray film showed that the heart was located on the right side of the chest, with the apex towards the right (Figure 4). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 5) revealed single ventricle with anatomical left ventricular morphology, single atrium and a common atrioventricular valve.

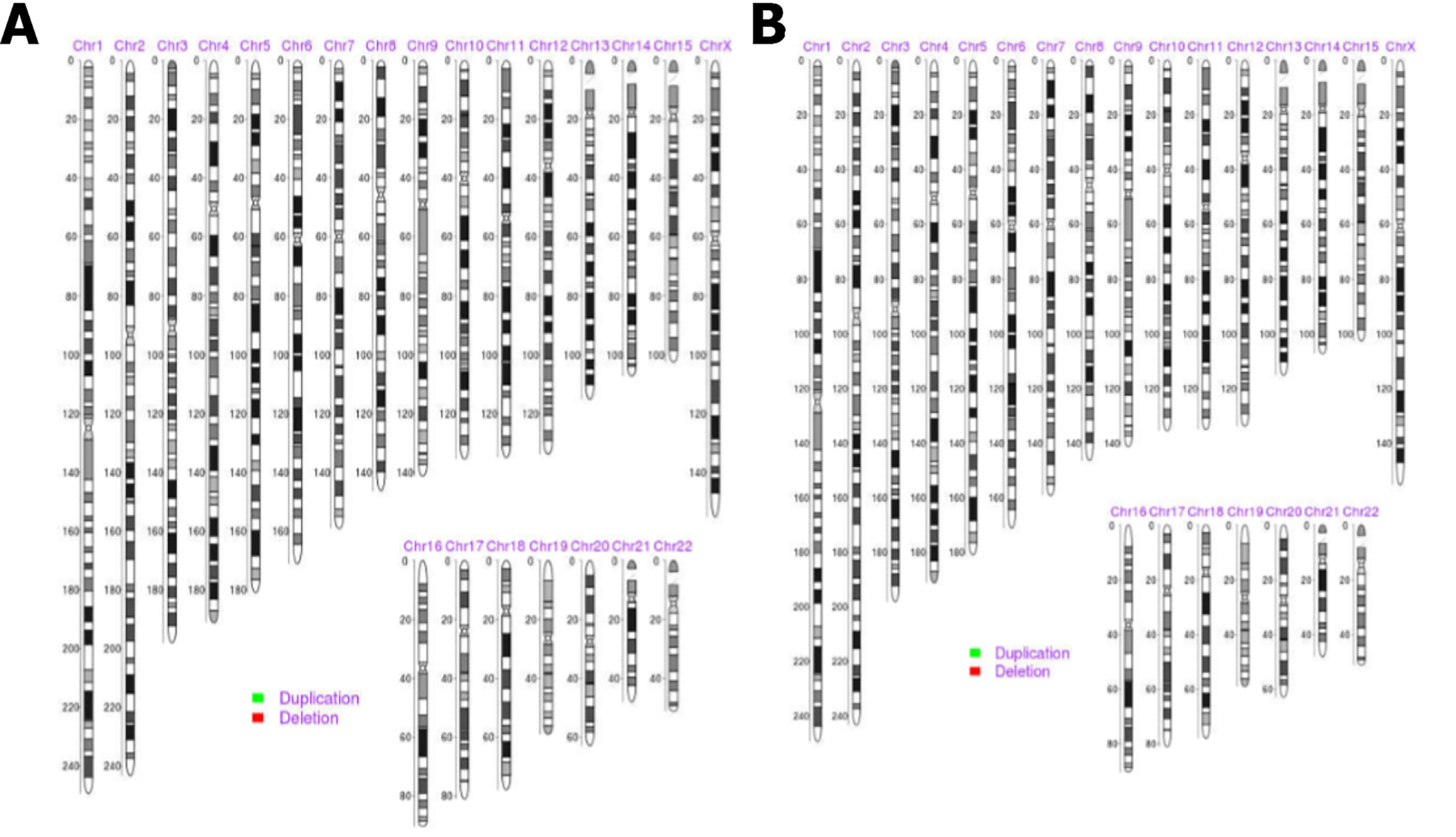

Other tests: chromosome karyotyping in blood cells and villous tissues showed no suppressive, pathogenic and clear chromosomal microdeletion/microduplication syndromes or aneuploidy abnormalities, based on the GRCH37/hg19 N reference genome, representing the X or Y chromosome (Figure 6).

Blood gas analysis showed a PaO2 of 44 mmHg (normal level: 80–100 mmHg) and a PaCO2 of 31.7 mmHg (normal level: 35–45 mmHg). Routine blood test revealed red blood cell count of 7.37 × 1012 (normal level: 3.8× 1012–5.1 × 1012), hemoglobin 209.0 g/L (normal level: 115–150 g/L), progesterone 9.3 nmol/L and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) at 4288.0 mIU/mL. The indicators of blood biochemistry, liver and renal functions, myocardial enzyme and coagulation function were all unremarkable.

The examination showed blood pressure (BP) of 134/52 mmHg, heart rate 137 beats/min, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, and 68% SPO2 (mask oxygen inhalation). After a 30-min rest, BP was 103/62 mmHg, heart rate 86 beats/min and SPO2 75%. The patient was conscious, and her average IQ was evaluated by Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Her height was 161 cm, weight 41 kg, body mass index 15.8, with high zygomatic arch, irregular teeth, and obvious cyanosis of the lips. No significant filling of the jugular vein was seen, and clubbing digits as a symptom of cyanotic heart disease and arachnodactyly related to Marfan’s syndrome were observed. The strongest point of the apex beat was located in the 5th intercostal space of the right midclavicular line, and a grade 3/6 systolic blowing murmur was heard along the right sternal border. The abdomen was soft, with the lower part slightly dilated and no tenderness, rebound tenderness, or muscle tension. No enlargement was palpated in subcostal areas of the liver and spleen. Gynecological examination revealed an unobstructed vagina containing moderate amounts of dark red blood. The uterine orifice was closed, with no tissue incarceration or significant active bleeding.

Menstrual, marital and childbearing history: the patient had regular menstrual periods, starting at age 14 years (menstruation, 5/25 d). She got married at age 24 years to a healthy husband. Consanguineous marriage was refused. Eight pregnancies were reported; all of which resulted in spontaneous abortions. She had no history of specific infections (e.g., rubella) during pregnancy, and no intake of teratogenic drugs or radiation exposure were reported. No known family history of congenital heart defects was reported.

The patient had a history of congenital heart disease (the specific type was unknown).

She had a history of cyanosis since birth, which was aggravated by crying and recurrent syncope since age 2 years. Normally, she was active and asymptomatic. Chest distress, shortness of breath and exacerbated cyanosis only occur during a heavy workload. Her last menstruation occurred on December 27, 2016. A detec rise in urinary hCG was found on January 10, 2017. Intrauterine pregnancy was revealed, but no embryo or fetal vascular pulsation was detected by B-ultrasound. She was advised re-examination within a week. However, for various reasons, she did not undergo any further check. Five days prior to revisit, she noticed vaginal bleeding and developed chest tightness, shortness of breath, dyspnea, and exacerbated cyanosis of the lips occurred 1 d prior to the visit.

A 40-year-old woman presented with cyanosis for 40 years, cessation of menstruation for > 3 mo, vaginal bleeding started 5 d ago, and chest tightness, shortness of breath and exacerbated cyanosis the day before.

The following diagnoses were: (1) Missed abortion; (2) Complex congenital heart disease with dextrocardia, single atrium, single ventricle, and grade III cardiac function; (3) Situs inversus totalis; and (4) Secondary erythrocytosis.

After admission, she rested in bed and was given high-flow mask oxygen inhalation to improve cardiac function. B-ultrasound-guided uterine aspiration was performed to absorb 8 g organized villus and 10 g decidual tissues, with little bleeding.

One day after the operation, the patient was discharged. Postoperatively, cyanosis and fatigue-induced shortness of breath were gradually relieved. Three days after the procedure, off-bed activities were reported, and vaginal bleeding stopped after 5 d. She returned to normal life after 1 wk. At 12, 24 and 36 mo after discharge, the patient revisited the hospital for evaluation. She could engage in daily housework and worked as an online salesperson. The patient has had no further pregnancy. After a cold, cyanosis was aggravated, and relieved after recovery. She reported no routine medication.

Only a few patients with two-chambered heart surviving to adulthood have been reported, including two in Poland aged 23 and 19 years[3], one in Iran aged 22 years[4], one in Sri Lanka aged 25 years[5], one in China aged 20 years[6], one in Japan aged 42 years[7] and one in the United States aged 25 years[8]. Here, we reported a rare case with two-chambered heart, situs inversus totalis and multiple miscarries (Figure 7). The current patient was 44 years old at last follow-up. She had undergone no surgical interventions and could tolerate multiple miscarriages and survived to date, which is rare in clinical practice. Familial single ventricle has been reported[9], and sisters with the same parents have been successively diagnosed with this disease, suggesting that such isolated, similar and rare congenital cardiac malformations might be associated with genetic factors.

The current patient had adverse pregnancy outcome and early abortion eight times, and genetic factors could not be entirely ruled out. Therefore, chromosomes in peripheral blood and intrauterine villus tissues were assessed, and no related chromosomal abnormalities were detected. The possibility of chromosomal anomalies was excluded. The 30%–50% increase in cardiac output is associated with pregnancy. For pregnant women with congenital heart defects, there is no safety net to balance the nonpregnant state[8]. The hemodynamic changes during pregnancy may have deleterious effects on cardiac function, and poor cardiac function may in turn lead to insufficient uterine perfusion and subsequent abortion. Markov et al[10] reported a woman with a two-chamber heart alone who survived to the age of 40 years and experienced multiple failed pregnancies (premature birth or miscarriage) for unknown reasons. In this case, B ultrasound showed that the angle between the uterine neck and the uterine body was located behind the uterus, indicating that the uterus was completely inverted. Although the sizes of the ovary and uterine were normal, the inverted uterine and hypoxia condition might be other causes of multiple miscarriages.

Consistent with Blackford’s study[11], the findings of familial single ventricular patients[9] and a long-term follow-up study of a 61-year-old patient with single ventricle[12] support that pulmonary stenosis might be the main reason for longer survival of single ventricular patients. In the current case, pulmonary subvalvular stenosis was present, and pulmonary vascular resistance was normal, with no significant pulmonary hypertension. This suggests that there may be less mixing of arteriovenous blood. In addition, the oxygen dissociation curve was shifted to the right, oxygen utilization was increased, and compensatory erythrocytosis and tolerance to hypoxia were found. Therefore, the patient could survive to adulthood. The formation of a two-chambered heart is likely associated with Marfan’s syndrome[13]. The present patient had arachnodactyly, a high palatal arch, dentition dislocation and irregularity, with no bone, eye or aorta abnormalities, and was suspected of Marfan’s syndrome and situs inversus totalis, which is clinically rare.

The current two-chambered heart patient has outlived all similar cases reported so far, and remains active, with no major health issues beyond the congenital heart malformation and multiple abortions.

The two-chambered heart is a complex congenital heart defect and few people survive to adulthood. Pregnancy may adversely affect cardiac function in patients with a two-chambered heart, and poor cardiac function may lead to hypoperfusion of the uterus and subsequent abortion. Patients with a two-chambered heart should seek appropriate counseling with regard to potential health risks.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Wenhong Tao, Ganjun Song and Hong Yu for their help in collecting medical records.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: de Melo FF, Ghimire R, Le PH, Naem AA S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Wang JL

| 1. | Sun PF, Ding GC, Zhang MY, He SN, Gao Y, Wang JH. Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease among Infants from 2012 to 2014 in Langfang, China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130:1069-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Moodie DS, Ritter DG, Tajik AJ, O'Fallon WM. Long-term follow-up in the unoperated univentricular heart. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53:1124-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Klisiewicz A, Michałek P, Szymański P, Hoffman P. Univentricular heart, common atrium, single atrio-ventricular valve--is it possible in humans? Kardiol Pol. 2004;61:274-276. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Nabati M, Bagheri B, Habibi V. Coincidence of total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage to the superior vena cava, common atrium, and single ventricle: a very rare condition. Echocardiography. 2013;30:E98-E101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lohithalingam P, Lakmini KMS, Weerasinghe S, Pereira T, Premaratna R. Long-term survival of a patient with single atrium and single ventricular heart: a case report. Ceylon Med J. 2018;63:80-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wei C, Xue X, Zhu G, Li M, Liu H, Peng H. A primigravida with single atrium and single ventricle. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123:160-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ogata H, Nakata T, Endoh A, Tsuchihashi K, Yonekura S, Tanaka S, Tsuda T, Kubota M, Iimura O. Scintigraphic imaging of a case of congenitally corrected transposition of the great vessels and an adult case of single atrium and single ventricle. Ann Nucl Med. 1989;3:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Seeds JW, Cefalo RC. Pregnancy with congenital heart disease: a two-chambered heart. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;127:213-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stephenson C, Franken EA, Ha-Upala S, Christian JC. Familial occurrence of single ventricle. Arch Dis Child. 1971;46:730-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Markov II, Verbinets AA, Kushch OO, Plakhtin DL. A rare variant of a congenital heart defect--a two-chamber heart combined with other anomalies. Kardiologiia. 1971;11:114-115. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Blackford LM, Hoppe LD. Functionally two chambered heart. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1931;41:1111-1122. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Oliver JM, Fdez-de-Soria R, Dominguez FJ, Ramos F, Calvo L, Ros J. Spontaneous long-term survival in single ventricle with pulmonary hypertension. Am Heart J. 1990;119:201-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McCracken AW. COR BILOCULARE. Br Heart J. 1962;24:126-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |