Published online Dec 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i35.12899

Peer-review started: March 8, 2022

First decision: April 5, 2022

Revised: May 5, 2022

Accepted: August 21, 2022

Article in press: August 21, 2022

Published online: December 16, 2022

Processing time: 280 Days and 18.4 Hours

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients’ expectations of treatment outcomes may differ by ethnicity.

To investigate treatment preferences of Jewish and Arabs patients.

This prospective survey ranked outcomes treatment preferences among Arab IBD patients, based on the 10 IBD-disk items compared to historical data of Jews. An anonymous questionnaire in either Arabic or Hebrew was distributed among IBD patients. Patients were required to rank 10 statements describing different aspects of IBD according to their importance to the patients as treatment goals. Answers were compared to the answers of a historical group of Jewish patients.

IBD-disk items of 121 Arabs were compared to 240 Jewish patients. The Jewish patients included more females, [151 (62.9%) vs 52 (43.3%); P < 0.001], higher education level (P = 0.02), more urban residence [188 (78.3%) vs 54 (45.4%); P < 0.001], less unemployment [52 (21.7%) vs 41 (33.9%); P = 0.012], higher income level (P < 0.001), and more in a partnership [162 (67.8%) vs 55 (45.4%); P < 0.001]. Expectations regarding disease symptoms: abdominal pain, energy, and regular defecation ranked highest for both groups. Arabs gave significantly lower rankings (range 4.29–6.69) than Jewish patients (range 6.25–9.03) regarding all items, except for body image. Compared to Arab women, Jewish women attached higher priority to abdominal pain, energy, education/work, sleep, and joint pain. Multivariable regression analysis revealed that higher patient preferences were associated with Jewish ethnicity (OR 4.77; 95%CI 2.36–9.61, P < 0.001) and disease activity. The more active the disease, the greater the odds ratio for higher ranking of the questionnaire items (1-2 attacks per year: OR 2.13; 95%CI 1.02–4.45, P = 0.043; and primarily active disease: OR 5.29; 95%CI 2.30–12.18, P < 0.001). Factors inversely associated with higher patient preference were male gender (OR 0.5; 95%CI 0.271-0.935, P = 0.030), UC (OR 0.444; 95%CI 0.241–0.819, P = 0.009), and above average income level (OR 0.267; 95%CI: 0.124–0.577, P = 0.001).

The highest priority for treatment outcomes was symptom relief. Patients preferences were impacted by ethnicity, gender, and socio-economic disparity. Understanding patients' priorities may improve communication and enable a personalized approach.

Core Tip: This prospective survey ranked preferences of treatment outcomes among Arab and Jewish inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, based on the 10 IBD-disk items. Symptom relief was the highest priority in both groups. Ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic disparity impact patients' rankings priorities for treatment outcomes. Arabs gave significantly lower rankings than Jewish patients regarding all items, except for body image. Jewish women, compared to Arabs, attached higher priority to abdominal pain, energy, education/work, sleep, and joint pain. Multivariable regression analysis revealed that higher patient preferences were associated with Jewish religion and disease activity.

- Citation: Naftali T, Richter V, Mari A, Khoury T, Shirin H, Broide E. Do inflammatory bowel disease patient preferences from treatment outcomes differ by ethnicity and gender? A cross-sectional observational study. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(35): 12899-12908

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i35/12899.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i35.12899

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is rising in both developed and developing cou

In a systematic review by Hou et al[2] differences in disease behavior were reported among various ethnic groups, including disease location, phenotype, family history, and extra-intestinal manifestations. As IBD behaves differently in ethnic groups, the difference may also manifest in different cultural and ethnic perceptions of the disease. Furthermore, variations across ethnic groups regarding treatment expectations and acceptability were demonstrated[3]. However, data on the impact of culture and ethnicity on IBD patients’ disease perception are scarce, and most studies are limited to one homo

Israel has an advantage of a mixed population with different ethnic groups residing in the same country. The prevalence of IBD is notoriously high in Ashkenazi Jews but is rapidly increasing among Arabs residing in Israel[5,6]. The clinical characteristics of IBD among Arab and Ashkenazi Jews were compared, but the cultural and ethnic disease perceptions, including patients’ preferences and priorities regarding treatment outcomes, have not been explored previously[7,8].

It seems that the patients’ treatment expectations do not always match those of the physician. Furthermore, factors related to a patient's response to treatment are not necessarily the patient's top priority. Patients’ preferences of treatment outcomes were not yet fully explored. To assess those pre

We conducted a prospective survey of Arab Israeli IBD patients and compared the results to a historical data set of Jewish Israeli IBD patients. We translated the previously used Hebrew questionnaire to Arabic so that the methods and questionnaire in both studies were the same.

The Israeli Crohn's and Colitis Foundation posted an anonymous questionnaire, which was addressed to IBD patients over 15 years old. This questionnaire was also used by local IBD clinics in the hospitals that participated in the study conducted from July 1 to October 31, 2020. The Ethics Committee of Shamir Medical Center approved the study on April 5, 2020, No. 0097-20-ASF. The Ethics Committee did not require informed consent because the questionnaire was answered anonymously and responding to the questionnaire was considered consent.

Questionnaires were delivered in either Arabic or Hebrew according to ethnicity. The data collected included demographic parameters (age, gender, ethnic origin, level of education, place of residence, and marital status), and socio-economic parameters (average work hours per week and income level). Clinical parameters included the presence of other co-morbidities, type of IBD, years since diagnosis, disease location in CD, current perianal disease, frequency of flares during the last three years, current treatment with steroids or biologics, and treatment response.

The IBD Disk 10-item questionnaire[9] based on the validated IBD-D[10] was used to assess patients’ desired treatment outcomes. This questionnaire includes 10 statements describing different aspects of IBD. To understand the patients’ therapeutic goals, we adjusted the items by ranking them in importance from 1 (less important) to 10 (most important) (Detailed in Table 1).

| Item | Please score how important it is to you that the medical treatment will improve each of the following parameters, at a score of 1: not important at all to 10: very important | Jewish, mean (SD) | Arab, mean (SD) | P value1 |

| Abdominal pain | Aches or pains in my stomach or abdomen | 9.03 (1.88) | 6.69 (2.83) | < 0.001 |

| Regulating defecation | Difficulty coordinating and managing defecation, including choosing and getting to an appropriate place for defecation and cleaning myself afterword | 8.8 (2.21) | 6.54 (3.05) | < 0.001 |

| Energy | Feeling rested and refreshed during the day, and improving feeling tired and without energy | 8.8 (2.06) | 6.59 (3.14) | < 0.001 |

| Education and work | Difficulty with school activities or studying, and/or difficulty with work or household activities | 7.81 (2.8) | 6.51 (3.28) | < 0.001 |

| Emotions | Felt sad, low or depressed, and/or worried or anxious | 7.62 (2.98) | 6.19 (3.26) | < 0.001 |

| Sleep | Difficulty sleeping, such as falling asleep, waking up frequently during the night or waking up too early in the morning | 7.6 (3.16) | 5.65 (3.55) | < 0.001 |

| Joint pain | Pains in the joints of my body | 7.33 (3.26) | 5.32 (3.69) | < 0.001 |

| Interpersonal interactions | Difficulty with personal relationships and/or difficulty participating in the community | 6.93 (3.26) | 6.06 (3.41) | 0.013 |

| Sexual function | Difficulty with the mental and/or physical aspects of sex | 6.52 (3.31) | 4.29 (3.38) | < 0.001 |

| Body image | Like the way my body or body parts look | 6.25 (3.25) | 5.61 (3.18) | 0.057 |

Categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were analyzed for normal distribution by performing QQ plot and histogram and were reported as median (interquartile range). Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical variables between Jewish and Arab patients. In order to compare between continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney test was employed.

Cluster analysis was used to classify patients into homogeneous subgroups according to their preferred IBD items. This was performed with a k-means method[11], which assigns each patient to one and only one cluster. The number of clusters was defined a priori as 2. Differences between clusters were assessed using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher's Exact Test for categorical variables.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to study the associations between ethnic groups and clusters while controlling for potential confounders. The logistic regression included 2 blocks. In the first block, the ethnic group was forced into the regression and in the second block backward method was applied (the WALD test was used as a criterion for removal, variables with P > 0.1 were removed). Age, gender, education, residence, partnership, work, income, and education were included as potential confounders. The last step was reported. Statistical significance was considered if P < 0.05 in a 2-sided test. SPSS software was used for statistical analysis (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, ver. 24, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States).

A total of 121 Arab IBD patients answered the questionnaire between July 1 and September 30, 2021. Results from the Arab patients were compared to historical data of 240 Jewish IBD patients who completed the same questionnaire from May to July 2020[12]. After combining these two populations, 361 patients were included in the analysis. The median age was 35 (interquartile range 27-46), not significantly different between Jewish and Arab patients. In the Jewish population, a higher percentage of females responded to the questionnaire than in the Arab population [151 (62.9%) vs 52 (43.3%); P < 0.001]. The Jewish IBD patients were characterized by higher education level (P = 0.02), more resided in urban areas (P < 0.001), and more were in a relationship with a partner (P < 0.001). Among the Arab group, 33.9% were unemployed compared to 21.7% among Jews (P = 0.012). Income was below average among 77.6% of Arab patients, compared to 51.6% of the Jewish population (P < 0.001; Table 2).

| Characteristic | Total, N = 361, n (%) | Jewish, n= 240, n (%) | Arab, n = 121, n (%) | P value1 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 35 (27-46) | 37 (27-47) | 33 (28-43) | 0.053 |

| Female | 203 (56.2) | 151 (62.9) | 52 (43.3) | < 0.001 |

| Years of education, median (IQR), (n = 353, missing = 8) | 12 (12-16) | 14 (12-16) | 12 (12-16) | < 0.001 |

| Education (n = 359, missing = 2) | 0.02 | |||

| Elementary school | 8 (2.2) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (5) | |

| High school | 147 (41) | 94 (39.3) | 53 (44.2) | |

| Higher education | 204 (56.8) | 143 (59.8) | 61 (50.8) | |

| Residence (n = 359, missing = 2) | < 0.001 | |||

| Urban | 242 (67.4) | 188 (78.3) | 54 (45.4) | |

| Rural | 117 (32.6) | 52 (21.7) | 65 (54.6) | |

| Marital status (n = 360, missing = 1) | < 0.001 | |||

| Relationship | 217 (60.3) | 162 (67.8) | 55 (45.4) | |

| Single | 119 (33) | 60 (25.1) | 59 (48.8) | |

| Widowed/divorced | 24 (6.7) | 17 (17.1) | 7 (5.8) | |

| Employed | 0.012 | |||

| No | 93 (25.8) | 52 (21.7) | 41 (33.9) | |

| Yes | 268 (74.2) | 188 (78.3) | 80 (66.1) | |

| Average number of hours worked per week, median (IQR), (n = 240, missing = 121) | 31 (10.25-41) | 40 (21-45) | 15 (8-36) | < 0.001 |

| Income level (n = 320, missing = 41) | < 0.001 | |||

| Below average | 192 (60) | 112 (51.6) | 80 (77.6) | |

| Average | 48 (15) | 36 (16.6) | 12 (11.7) | |

| Above average | 80 (25) | 69 (31.8) | 11 (10.7) | |

| Co-morbidity2 | 72 (19.9) | 58 (24.2) | 14 (11.6) | 0.005 |

| Disease type (n = 359, missing = 2) | 0.734 | |||

| Crohn's disease | 240 (66.5) | 161 (68.8) | 79 (66.4) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 113 (31.3) | 73 (31.2) | 40 (33.6) | |

| Undetermined IBD | 6 (1.7) | 6 | 0 | |

| Years since diagnosis, median (IQR), (n = 328, missing = 33) | 8 (4-14) | 9 (4-17) | 6 (3-10) | 0.01 |

| IBD Disease activity last three years (n = 347, missing = 14) | 0.97 | |||

| Mostly quiet | 85 (24.5) | 57 (24.9) | 28 (23.7) | |

| 1-2 attacks | 139 (40) | 91 (39.7) | 48 (40.7) | |

| Primarily active disease | 123 (35.5) | 81 (35.4) | 42 (35.6) | |

| Current steroid treatment | 26 (7.2) | 19 (7.9) | 7 (5.7) | 0.459 |

| Current biologics treatment | 216 (59.8) | 143 (59.6) | 73 (60.3) | 0.889 |

| Treatment effective (n = 328, missing = 33) | 0.754 | |||

| No-0 | 35 (10.7) | 24 (11.2) | 11 (9.6) | |

| Yes-2 | 204 (62.2) | 130 (60.7) | 74 (64.9) | |

| Partially-1 | 89 (27.1) | 60 (28) | 29 (25.4) | |

We analyzed data from 361 patients, including 240 (66.5%) CD patients and 113 (31.3%) UC patients and 6 (1.7%) undetermined IBD. The distribution of both diseases between Jews and Arabs was not significantly different. The extent of CD was ileal in 35.7%, colono-ileal in 14.7%, isolated colonic in 10.3%, and for 8.5% no accurate data was available. Perianal involvement was reported in 13.4% of CD patients. Regarding disease severity, 35.3% had active disease, 59.8% were treated with biologics, and 7.2% received steroids. Biologic treatment was significantly more common in CD patients [110 (71%) vs 27 (39.1%), respectively, P < 0.001]. Both CD and UC patients responded similarly to biologic treatment (Table 2).

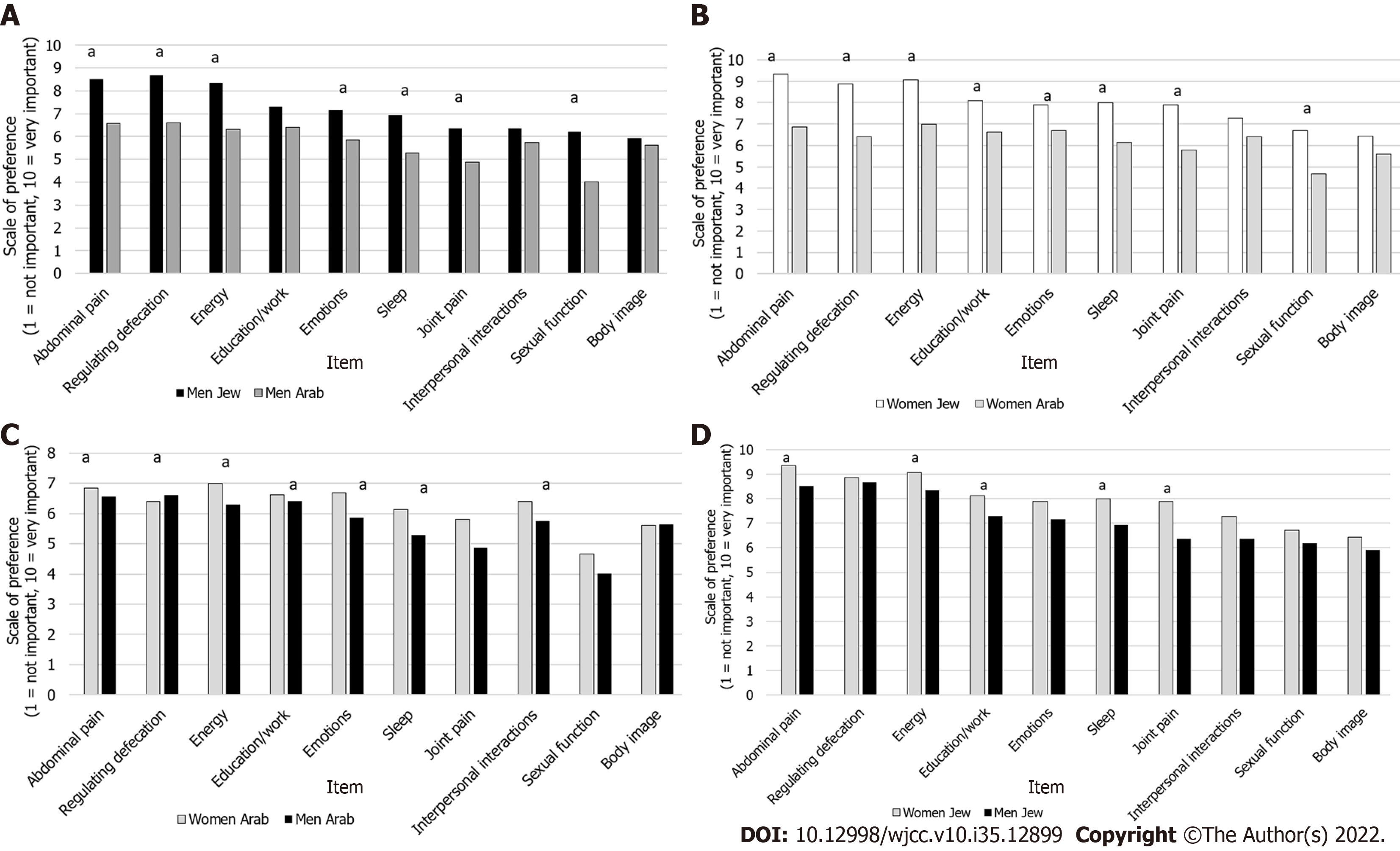

As a group, the Arab patients had lower rankings (range 6.69–4.29) than the Jewish patients (range 9.03–6.25). The ranking of the Jewish patients was significantly higher in all items except for body image. Despite that, the items with the highest priority were the same in both groups, with abdominal pain, energy level, and regular defecation ranking highest (Table 1). We further analyzed the data combining both ethnicity and gender and found that the differences between Jews and Arabs in the ranking of the items were maintained. Both Jewish and Arab men ranked education/work, body image, and interpersonal interactions at the same level of importance (Figure 1A), whereas the women ranked only body image and interpersonal interactions at the same level of importance (Figure 1B). When comparing the ranking of the items between genders of the same ethnic group, there were no differences between Arab men and women (Figure 1C), however, among Jewish patients, women attached higher priority than men did to abdominal pain, energy, education/work, sleep, and joint pain (Figure 1D).

In order to better characterize the features that impact patients’ preferences regarding treatment outcomes, we performed a cluster analysis dividing the patients into Cluster 1 -those who gave a lower score for most parameters -included 103 patients and Cluster 2- those who gave a higher score for most parameters- included 235 patients. Cluster analysis did not include patients with missing data; hence 23 patients were excluded. Preferences according to clusters are shown in Figure 2.

Compared to cluster 1, cluster 2 was characterized by more women [146 (62.4%) vs 42 (40.8%), P < 0.001], more Jews [178 (75.7%) vs 51 (49.5%), P < 0.001], more urban residents [174 (74.7) vs 53 (51.5), P < 0.001], higher average number of working hours per week [mean 32.5 (± 16.1) vs 25.1 (± 17.1), P = 0.003] and lower income level [141 (64.1%) vs 41 (48.8%), P = 0.011], in cluster 2 vs cluster 1, respectively. Cluster 2 included more patients with CD [167 (71.1%) vs 59 (58.4%), P = 0.011], more with active disease [101 (45.1%) vs 18 (17.8%), P < 0.001], more currently using steroids [24 (13%) vs 2 (3.9%), P = 0.008], and lower response to treatment [124 (56.1%) vs 72 (77.4%), P = 0.002], in cluster 2 vs cluster 1, respectively.

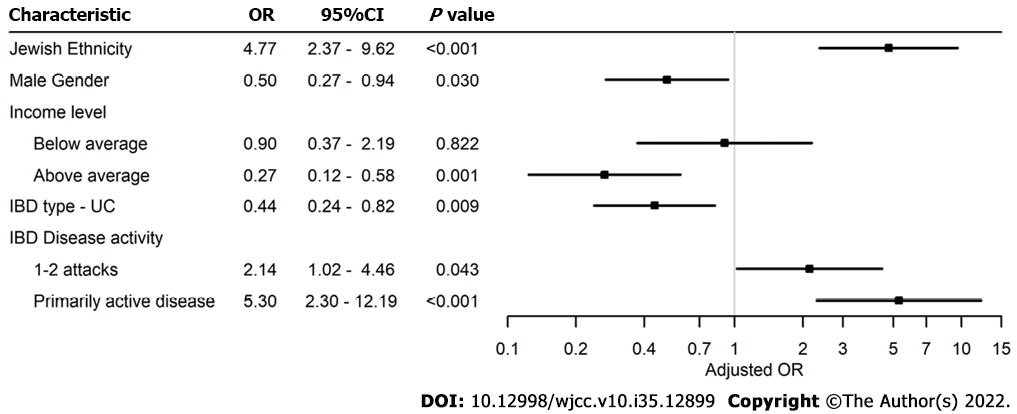

After adjusting for age, gender, education, residence, partnership, work, and income, 76 patients were not included due to missing data, leaving 285 patients. Factors associated with higher patients' preferences (Cluster 2) were Jewish religion [odds ratio (OR) 4.77; 95%CI 2.36–9.61, P < 0.001] and disease activity. Disease activity was graded as either 1-2 attacks per year or primarily active disease. The more active the disease, the higher the odds ratio for being in cluster 2 (1-2 attacks: OR 2.13; 95%CI 1.02–4.45, P = 0.043 and primarily active disease: OR 5.29; 95%CI 2.30–12.18, P < 0.001). UC (OR 0.444; 95%CI 0.241–0.819, P = 0.009), male gender (OR 0.5; 95%CI 0.271–0.935, P = 0.030), and above average income level (OR 0.267; 95%CI 0.124–0.577, P = 0.001) were less likely to belong to Cluster 2 (Figure 3).

The results of this study indicate that patients’ preferences regarding treatment outcomes are influenced by ethnicity and gender. Jewish patients ranked most items higher than Arab patients. Additionally, women in both ethnic groups ranked most items higher than men. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the impact of ethnicity and gender on patients’ preferences in the IBD population. When treating a chronic disease such as IBD, synchronizing patients’ expectations of treatment outcome with the physician's treatment goals is crucial for patient compliance and hence for successful treatment, as well as an open, trusting patient-physician relationship[13].

Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) were extensively studied over the last years and are considered to be an important measure of treatment success. Moreover, studies that focused on PROMs or quality of life did not compare ethnic groups to determine whether they differ regarding treatment goals and outcomes[14,15]. Most studies focused on PROMs and not on patients’ preferences. In a study comparing 44 unique PROMs from various countries, the authors did not refer to possible ethnic or cultural differences[16].

Patients’ expectations may be influenced by their social and economic backgrounds, as well as by their cultural and ethnic origins. Casellas et al[17] investigated patients’ preferences but did not refer to the influence of patients’ ethnicity, gender, or disease parameters on expectations from treatment.

The importance of ethnicity in influencing patients’ expectations has been demonstrated in other diseases. In malignant diseases, ethnicity affected patients’ estimation of possible cure; however, that study could not conclude whether the differences were due to poor communication due to language gaps or ethnic differences[18]. Our study overcame this obstacle by addressing each ethnic group in its native language. In non-cancer pain, Meints et al[19] found that, regarding pain treatment, the expectations of patients from minority groups were lower. Lavernia et al[20] reported that patients’ expectations about arthroplasty differed by ethnicity.

The current study aimed to further illuminate this important interrelationship in the IBD population. We compared two populations with different cultural and ethnic backgrounds living in the same country. The IBD Disk application was developed to assess the disability caused by the disease[9], but we used it to evaluate patients’ expectations from treatment according to ethnicity and gender. We observed that patients of Jewish ethnicity attached higher importance to most IBD disk parameters than did the Arab ethnic group. This difference is most likely due to different lifestyles and cultural in

Women of both ethnic origins attached higher importance to most parameters compared to males, with an OR of 5. Other studies have also demonstrated gender-related differences regarding symptom severity and disease outcomes. Women were more affected by psychosocial factors, evaluated their symptoms as being more severe, and were more concerned about body image, being attractive, fertility, and feeling alone[21-23]. Therefore, it is not surprising that women attach more importance to treatment outcomes than men do.

Both populations ranked improvement of disease symptoms, such as diarrhea and abdominal pain, as a high priority in their expectations, whereas body image and sexual function were graded as less important. This finding is further supported by Casellas et al[17] who demonstrated that IBD patients' primary aims of treatment are to improve quality of life and to control symptoms, with highest priority attached to relief of abdominal pain.

This study had a few limitations. Only ambulatory patients were included. Our results were based on patients' self-reports without confirmation from their medical files. Whereas most Jewish patients answered the questionnaires using social media, half of the Arab patients answered them in paper form during a clinic visit, which may have created a selection bias between the two populations. The strengths of our study are that each ethnic group received the questionnaire in their native language. In addition, the questionnaire was distributed to all IBD patients throughout Israel and was not limited to a single medical center. Our study highlights the importance of a personal approach to each patient. Patients come from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds and one size does not fit all. The clarification of treatment priorities may enable physicians to better understand patients’ expectations.

To the best of our knowledge, this study explored for the first time, the influence of ethnicity on IBD patient preferences regarding treatment outcomes. We found that Jewish ethnicity, female gender, and low-income level were associated with higher rankings of priorities for IBD treatment outcomes. Regardless of the ethnic and cultural differences, symptom relief is the highest priority in both ethnic groups. Understanding patients' priorities may improve communication with physicians and enable a more personalized approach to disease management.

When directing a treatment plan, physicians should be alert to the different expectations of different gender and ethnic groups. These expectations need to be taken into account to improve patients’ compliance and treatment outcomes.

Ethnicity, gender, disease activity, and income have an important impact on the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients’ preferences when evaluated according to the IBD disk items.

Arab IBD patients (121) were compared to historical data of Jewish patients (240). Arabs gave significantly lower rankings than Jewish patients except for body image. Multivariable regression analysis revealed that higher patient preferences were associated with Jewish ethnicity and disease activity. Factors inversely associated with higher patient preference were male gender, UC, and above-average income level.

We conducted a prospective survey of Arab Israeli IBD patients by using the IBD disk platform and compared the results to a historical data set of Jewish Israeli IBD patients.

To assess patients’ preferences and treatment goals in a population of Arab patients by using the IBD disk format, and to compare them to the preferences and treatment goals of Jewish patients residing in the same country and treated by the same healthcare system.

Acknowledging and mapping the different perceptions and expectations of patients from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds may improve the patient-physician relationship. This will enable a personalized treatment approach, hence improving patient compliance and treatment outcomes.

The prevalence of IBD in non-Caucasian populations is growing. Different cultural and ethnic per

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Israel

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ferreira-Duarte M, Portugal; Rodrigues AT, Brazil; Wen XL, China S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Afzali A, Cross RK. Racial and Ethnic Minorities with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the United States: A Systematic Review of Disease Characteristics and Differences. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2023-2040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hou JK, El-Serag H, Thirumurthi S. Distribution and manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in Asians, Hispanics, and African Americans: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2100-2109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Juarez G, Ferrell B, Borneman T. Cultural considerations in education for cancer pain management. J Cancer Educ. 1999;14:168-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bojic D, Bodger K, Travis S. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in inflammatory bowel disease: New data. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017;11:S576-S585. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zvidi I, Boltin D, Niv Y, Dickman R, Fraser G, Birkenfeld S. The Incidence and Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Jewish and Arab Populations of Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2019;21:194-197. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Stulman MY, Asayag N, Focht G, Brufman I, Cahan A, Ledderman N, Matz E, Chowers Y, Eliakim R, Ben-Horin S, Odes S, Dotan I, Balicer RD, Benchimol EI, Turner D. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Israel: A Nationwide Epi-Israeli IBD Research Nucleus Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1784-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lerner A. One Size Doesn’t Fit All: IBD in Arabs and Jews in Israel, Potential Environmental and Genetic Impacts. J Clin Gastroenterol Treat. 2017;3:5-7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Zvidi I, Fraser GM, Niv Y, Birkenfeld S. The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in an Israeli Arab population. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2013;7:e159-e163. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ghosh S, Louis E, Beaugerie L, Bossuyt P, Bouguen G, Bourreille A, Ferrante M, Franchimont D, Frost K, Hebuterne X, Marshall JK, OʼShea C, Rosenfeld G, Williams C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Development of the IBD Disk: A Visual Self-administered Tool for Assessing Disability in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:333-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cieza A, Sandborn WJ, Coenen M, Chowers Y, Hibi T, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G, Colombel JF; International Programme to Develop New Indexes for Crohn's Disease (IPNIC) group. Development of the first disability index for inflammatory bowel disease based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Gut. 2012;61:241-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Macqueen J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations [Internet]. |

| 12. | Naftali T, Richter V, Mari A, Khoury T, Shirin H, Broide E. The inflammatory bowel disease disk application: A platform to assess patients' priorities and expectations from treatment. J Dig Dis. 2021;22:582-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rubin DT, Siegel CA, Kane SV, Binion DG, Panaccione R, Dubinsky MC, Loftus EV, Hopper J. Impact of ulcerative colitis from patients' and physicians' perspectives: Results from the UC: NORMAL survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:581-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Albach CA, Wagland R, Hunt KJ. Cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of generic and cancer-related patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for use with cancer patients in Brazil: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:857-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Verissimo R. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: Psychometric evaluation of an IBDQ cross-culturally adapted version. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2008;17:439-444. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Van Andel EM, Koopmann BDM, Crouwel F, Noomen CG, de Boer NKH, van Asseldonk DP, Mokkink LB. Systematic review of development and content validity of patient-reported outcome measures in inflammatory bowel disease: Do we measure what we measure? J Crohn’s Colitis. 2020;14:1299-1315. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Casellas F, Herrera-de Guise C, Robles V, Navarro E, Borruel N. Patient preferences for inflammatory bowel disease treatment objectives. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:152-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tchen N, Bedard P, Yi QL, Klein M, Cella D, Eremenco S, Tannock IF. Quality of life and understanding of disease status among cancer patients of different ethnic origin. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Meints SM, Cortes A, Morais CA, Edwards RR. Racial and ethnic differences in the experience and treatment of noncancer pain. Pain Manag. 2019;9:317-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lavernia CJ, Contreras JS, Parvizi J, Sharkey PF, Barrack R, Rossi MD. Do patient expectations about arthroplasty at initial presentation for hip or knee pain differ by sex and ethnicity? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2843-2853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Maunder R, De Rooy Phd E, Moskovitz D. Influence of sex and disease on illness-related concerns in inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | de Rooy EC, Toner BB, Maunder RG, Greenberg GR, Baron D, Steinhart AH, McLeod R, Cohen Z. Concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a clinical population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1816-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Appelbaum MI. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Functional status and patient worries and concerns. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1379-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |