Published online Nov 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.11949

Peer-review started: July 13, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 27, 2022

Accepted: October 9, 2022

Article in press: October 9, 2022

Published online: November 16, 2022

Processing time: 117 Days and 14.9 Hours

Asherman’s syndrome is characterized by reduced menstrual volume and adhesions within the uterine cavity and cervix, resulting in inability to carry a pregnancy to term, placental malformation, or infertility. We present the case of a 40-year-old woman diagnosed with Asherman’s syndrome who successfully gave birth to a live full-term neonate after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis under laparoscopic observation, intrauterine device insertion, and Kaufmann therapy.

A 40-year-old woman (Gravida 3, Para 0) arrived at our hospital for specialist care to carry her pregnancy to term. She had previously undergone six sessions of dilation and curettage owing to a hydatidiform mole and persistent trophoblastic disease, followed by chemotherapy. She subsequently became pregnant twice, but both pregnancies resulted in spontaneous miscarriages during the first trimester. Her menstrual periods were very light and of short duration. Hysteroscopic adhesiolysis with concurrent laparoscopy was performed, and Asherman’s syndrome was diagnosed. The uterine adhesions covered the area from the in

Hysteroscopic adhesiolysis with concurrent laparoscopy enables identification and resection of the affected area and safe and accurate surgery, without complications.

Core Tip: Adhesion dissection under laparoscopic monitoring in Asherman's syndrome is useful not only for avoiding the risk of surgical complications such as uterine perforation, but also for intraperitoneal observation to investigate the cause of infertility. Kaufman therapy and the use of an indwelling intrauterine device were useful for preventing postoperative recurrence of intrauterine adhesions.

- Citation: Kakinuma T, Kakinuma K, Matsuda Y, Ohwada M, Yanagida K. Successful live birth following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis under laparoscopic observation for Asherman’s syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(32): 11949-11954

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i32/11949.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.11949

Asherman’s syndrome is a condition in which mechanical damage to the endometrium or infection results in intrauterine adhesions (IUAs) and thinning of the endometrium, leading to menstrual abnormalities, such as hypomenorrhea, amenorrhea, and menstrual pain, as well as infertility due to implantation failure. Asherman’s syndrome is usually characterized by light menstrual periods[1]. IUAs were first reported in 1895 by Fritsch, and the condition known as Asherman’s syndrome was first described by Asherman in 1950[2,3]. In > 90% of reported cases, Asherman’s syndrome develops following dilation and curettage (D&C)[4]; however, it has also been frequently reported after myomectomy, intrauterine infection, radiotherapy, and uterine arterial embolization (UAE) and is reportedly present in 4.6% of patients with infertility[5].

Hysteroscopic adhesion removal surgery is indicated to treat Asherman’s syndrome if symptoms such as menstrual disorders and infertility are caused by uterine cavity adhesions. Monitoring during hysteroscopic surgery is required to reduce the risk of uterine perforation. In addition to surgery, the treatment of Asherman’s syndrome involves appropriate postoperative management to prevent additional causes of infertility. Herein, we report the use of hysteroscopic adhesiolysis under laparoscopic monitoring to make intrapelvic observations and reduce the risk of intraoperative uterine perforation in a woman with Asherman’s syndrome who subsequently gave birth successfully.

A 40-year-old gravida 3 para 0 (3020) woman presented to our hospital for specialist care with a desire to carry a pregnancy to term. She had attained menarche at 13 years of age, with a regular, 28-d menstrual cycle.

She had previously undergone six sessions of D&C for a hydatidiform mole and persistent trophoblastic disease, followed by chemotherapy (methotrexate). She had also become pregnant twice; however, both pregnancies ended in spontaneous miscarriages.

She had also become pregnant twice; however, both pregnancies ended in spontaneous miscarriages.

She had attained menarche at 13 years of age, with a regular, 28-d menstrual cycle.

Hysteroscopic adhesiolysis with concurrent laparoscopy was performed, and Asherman’s syndrome was diagnosed.

The uterine adhesions covered the area from the internal cervical os to the uterine fundus.

Postoperative Kaufmann therapy was administered, and endometrial regeneration was confirmed using hysteroscopy.

Blood tests for hormones were unremarkable, and transvaginal ultrasonography showed endometrial thinning (4–5 mm) in the ovulatory and secretory phases. Hysterosalpingography was attempted; however, the hysterosalpingography catheter was dislodged, and the procedure failed. A flexible hysteroscope with a 3.8-mm-diameter tip was introduced into the cervical os. The tip was covered with white tissue through which an insertion route could not be managed, preventing the hysteroscope from advancing further. Asherman’s syndrome was diagnosed based on these findings [American Fertility Society adhesion score, 8 points (moderate)]. Hysteroscopy with concurrent laparoscopy was conducted to examine the interior pelvic cavity for safe and effective adhesiolysis after obtaining written informed consent from the patient.

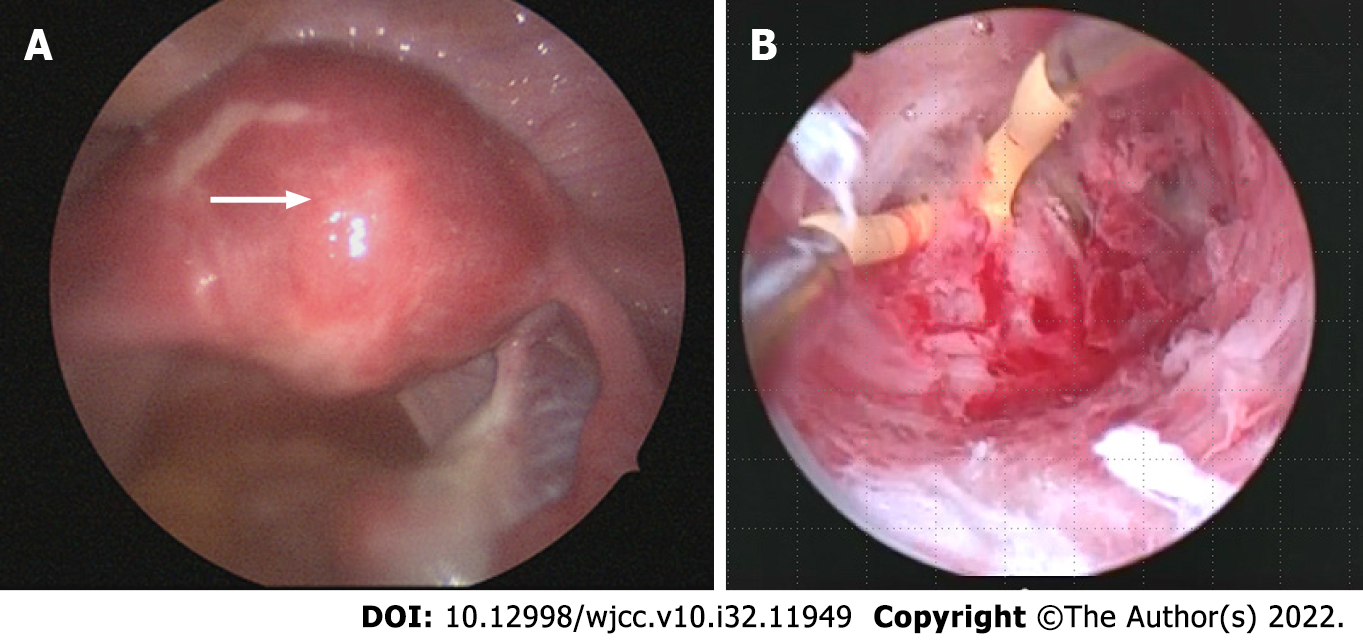

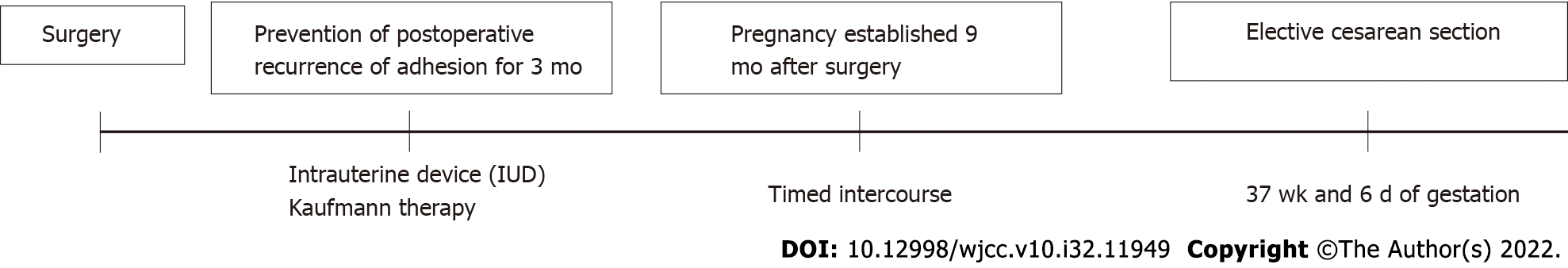

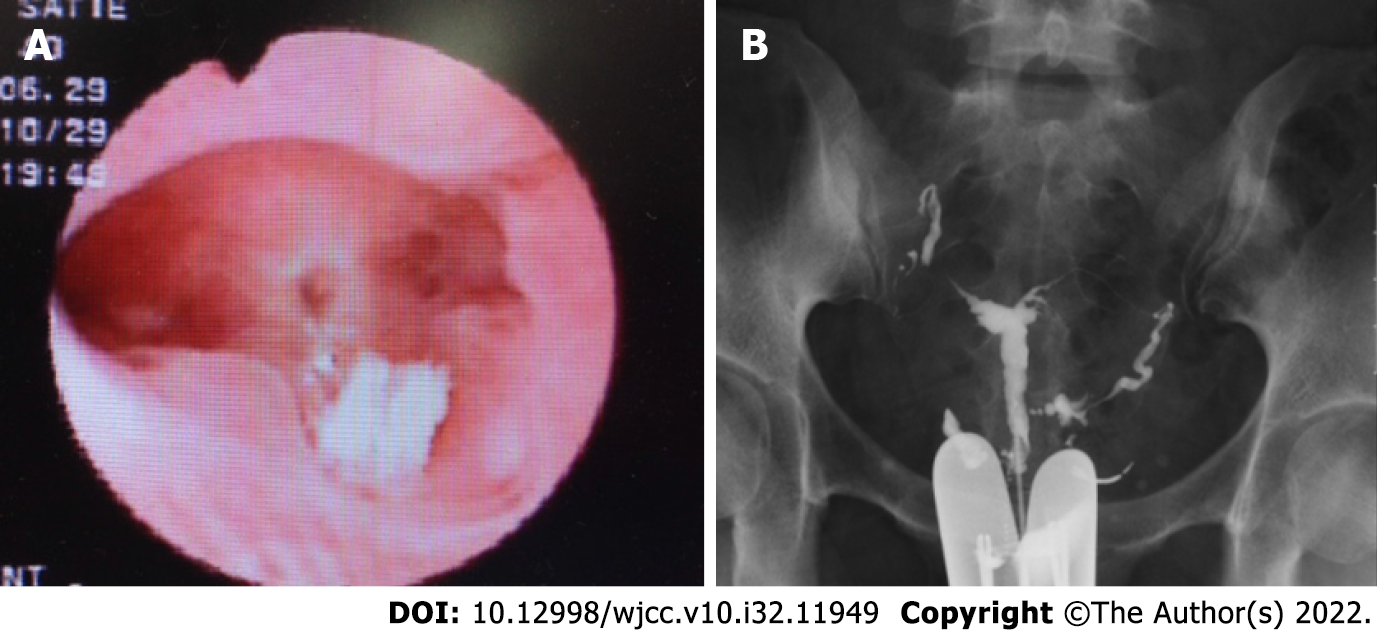

Upon hysteroscopy, careful adhesiolysis was performed through blunt dissection with a monopolar electric scalpel, while observing the hysteroscopic illumination with the laparoscope from the abdominal cavity side. This prevented excessive uterine wall thinning (Figure 1A and B). The surgery was completed upon sufficient adhesiolysis, and both fallopian tube orifices were identifiable. The postoperative course is shown in Figure 2. An intrauterine device (IUD) was placed to prevent postoperative adhesions, and Kaufmann therapy was administered for 3 mo. Hysteroscopic examination performed 3 mo postoperatively showed no adhesion recurrence at the internal cervical os or in the uterine corpus or fundus, with definite endometrial regeneration (Figure 3A). Hysterosalpingography conducted during the same period demonstrated contrast egress toward the fimbriae of both fallopian tubes and subsequent leakage into the abdominal cavity (Figure 3B).

Postoperatively, the patient’s menstruation was heavier, and the duration increased from 2 to 6 d. Following timed intercourse, she became pregnant 9 mo postoperatively. Cervical insufficiency was diagnosed at 22 wk of gestation, and a cervical cerclage (Shirodkar cerclage) was applied. The pregnancy was uneventful thereafter, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed at 34 wk of gestation showed no signs of placenta accreta or morphological abnormalities. Despite the absence of any sign of placenta accreta on diagnostic imaging, its possibility could not be excluded. Therefore, elective cesarean section was performed at 37 wk and 6 d of gestation to avoid the risk of uterine rupture. The woman delivered a live neonate weighing 2310 g with Apgar scores of 8 and 9 in the 1st and 5th minutes, respectively. The umbilical cord arterial pH was 7.25. The placenta exhibited partial adhesions (placenta increta); however, successful extrusion was achieved following blunt dissection from the muscle layer. The postpartum course was uneventful, and she was discharged on postoperative day 7.

Here, we describe a case involving a 40-year-old woman with Asherman’s syndrome who could con

Asherman’s syndrome is characterized by partial or widespread adhesions in the uterine cavity, which are associated with menstrual abnormalities, infertility, and placental abnormalities. The syndrome develops when the endometrium is damaged due to trauma or ischemia. If this damage extends beyond the functional layer of the endometrium into the basal layer, the endometrial epithelium cannot regenerate, and endometrial surface adhesions form. This presentation is caused by surgical abortion in many cases, although it may also develop owing to other causes, including myomectomy, intrauterine infections, radiotherapy, or UAE[5]. The absence of part or all of the endometrial tissue and the resulting IUAs prevent normal thickening of the endometrium during the menstrual cycle, causing uterine amenorrhea or uterine infertility.

In terms of its effect on pregnancy, in particular, Asherman’s syndrome is responsible for high rates of infertility, miscarriage, implantation failure during assisted reproduction, and placental abnormalities[6-8]. We considered that our patient had developed severe Asherman’s syndrome due to repeated D&C for a hydatidiform mole and persistent trophoblastic disease.

Surgery is indicated for treating patients with Asherman’s syndrome whose IUAs are causing symptoms such as menstrual irregularities and infertility, with hysteroscopic adhesiolysis considered the gold standard treatment. IUAs have the gross appearance of white, fibrous, granulation tissue, but this appearance changes to red or pink-colored uterine muscle tissue if the hysteroscope enters the normal muscle layer; therefore, the device must be advanced cautiously when detaching the adhesions. During the procedure, it is of paramount importance to avoid blind manipulation and to stay constantly aware of the device’s orientation within the uterine cavity, using the fallopian tube orifices as a landmark, taking care not to perforate the uterus. Recent studies have reported that transabdominal ultrasonography and laparoscopy are useful for monitoring during hysteroscopic surgery[9,10]. Although laparoscopy is more surgically invasive and expensive than ultrasonography, we performed hysteroscopic adhesiolysis under laparoscopic observation to prevent complications such as endometriosis, evaluate the fallopian tubes (for patency and surrounding adhesions), and prevent the uterus from rotating. Keeping the hysteroscope’s light source visible under laparoscopic observation enables safe and effective resection of IUAs.

However, adhesions commonly recur after adhesiolysis. Indeed, the more severe the adhesions, the higher the recurrence rate[1]. Therefore, care must be taken to prevent this from occurring. Methods of preventing the recurrence of adhesions include the following: (1) IUD insertion or the temporary placement of a Foley catheter within the uterus as a physical barrier to prevent contact with the damaged endometrium; (2) coating the damaged endometrium with hyaluronic acid gel or carboxymethyl cellulose as an adhesion barrier; (3) hormone therapy to promote endometrial regeneration; and (4) second-look hysteroscopy early after surgery[11-15].

For our patient, our efforts to prevent the recurrence of adhesions included IUD insertion at the end of the surgery and Kaufmann therapy which was started 1 mo postoperatively. Given that the IUD insertion should last for 3 mo, we considered that re-evaluation while the IUD was in place would be challenging; therefore, a second-look hysteroscopy was conducted 3 mo postoperatively.

The IUAs in the present case were widespread and severe. However, postoperative hysteroscopy showed that endometrial regeneration was apparent throughout the uterine cavity. Furthermore, the endometrium had thickened from 4–5 mm preoperatively to 8–9 mm postoperatively, indicating a good postoperative course.

Careful monitoring of the course of pregnancy after surgery for Asherman’s syndrome is necessary. Deans et al[16] reviewed the data of 696 women who delivered a child after adhesiolysis. The authors found that 17 of the women exhibited placental abnormalities such as placenta accreta or placenta previa, 8 required total hysterectomy, and 2 had uterine rupture. Furthermore, the premature birth rate was 40%–50%. Guo et al[3] also reported higher ectopic pregnancy rates, cervical insufficiency, placenta previa, placenta accreta, premature separation of normally implanted placenta, premature rupture of membranes, stillbirth, and neonatal death in women who became pregnant after intrauterine adhesion removal, compared to the general female population[3,5]. Our patient was diagnosed with cervical insufficiency at 22 wk of gestation, and cervical cerclage was performed. Subsequently, the pregnancy was unproblematic, and MRI performed at 34 wk of gestation showed no obvious signs of placenta accreta or morphological abnormalities, such as thinning of the uterine wall. Regarding the described patient, we deliberated whether her baby should be delivered vaginally or by cesarean section. We decided to perform an elective cesarean section to ensure rapid and flexible management of placenta accreta, if present, and avoid uterine rupture. During the cesarean section, careful manual manipulation was required to detach the placenta because placental adhesions (placenta increta) were present. The manual detachment may have been more difficult after vaginal birth; therefore, a cesarean section was indeed the most appropriate option for this patient. Pregnancy and delivery outcomes post-treatment for Asherman’s syndrome remain unclear, and decisions concerning the delivery method are at the individual’s discretion. Further studies involving larger numbers of patients are needed to determine indicators for the methods of managing pregnancy and delivery in women with Asherman’s syndrome.

We reported the treatment of a patient with Asherman’s syndrome who delivered a healthy infant after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis under laparoscopic observation at our hospital. The concurrent use of laparoscopy during hysteroscopic surgery for Asherman’s syndrome enabled clearer observation of the condition of the pelvic cavity and a safer procedure by the coordinated use of a hysteroscope and laparoscope. Furthermore, measures to prevent postoperative adhesions were taken. Complications in pregnancy following surgery for Asherman’s syndrome are frequent; careful perinatal management is required.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aydin S, Turkey; Peitsidis P, Greece S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Hanstede M, Emanuel MH. Reproductive Outcomes of 10 Years Asherman's Surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:S14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Asherman JG. Traumatic intra-uterine adhesions. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1950;57:892-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Guo EJ, Chung JPW, Poon LCY, Li TC. Reproductive outcomes after surgical treatment of asherman syndrome: A systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;59:98-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ. Intrauterine adhesions: an updated appraisal. Fertil Steril. 1982;37:593-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Baradwan S, Baradwan A, Al-Jaroudi D. The association between menstrual cycle pattern and hysteroscopic march classification with endometrial thickness among infertile women with Asherman syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Hanstede MMF, van der Meij E, Veersema S, Emanuel MH. Live births after Asherman syndrome treatment. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:1181-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang Y, Zhu X, Zhang T, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Lin X. Analysis of risk factors for obstetric outcomes after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis for Asherman syndrome: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;156:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang J, Movilla P, Morales B, Wang J, Williams A, Reddy H, Chen T, Tavcar J, Morris S, Loring M, Isaacson K. Effects of Asherman Syndrome on Maternal and Neonatal Morbidity with Evaluation by Conception Method. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1357-1366.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamamoto N, Takeuchi R, Izuchi D, Yuge N, Miyazaki M, Yasunaga M, Egashira K, Ueoka Y, Inoue Y. Hysteroscopic adhesiolysis for patients with Asherman's syndrome: menstrual and fertility outcomes. Reprod Med Biol. 2013;12:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Simsir C, Var T, Namli Kalem M. Hysteroscopic treatment of Asherman's syndrome. Cumhuriyet Med J. 2019;41:443-449. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Conforti A, Alviggi C, Mollo A, De Placido G, Magos A. The management of Asherman syndrome: a review of literature. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kresowik JD, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ, Ryan GL. Ultrasound is the optimal choice for guidance in difficult hysteroscopy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:715-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang JH, Chen MJ, Wu MY, Chao KH, Ho HN, Yang YS. Office hysteroscopic early lysis of intrauterine adhesion after transcervical resection of multiple apposing submucous myomas. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1254-1259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Robinson JK, Colimon LM, Isaacson KB. Postoperative adhesiolysis therapy for intrauterine adhesions (Asherman's syndrome). Fertil Steril. 2008;90:409-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dreisler E, Kjer JJ. Asherman's syndrome: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:191-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Deans R, Abbott J. Review of intrauterine adhesions. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:555-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |