Published online Oct 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11190

Peer-review started: July 25, 2022

First decision: August 22, 2022

Revised: August 27, 2022

Accepted: September 8, 2022

Article in press: September 8, 2022

Published online: October 26, 2022

Processing time: 87 Days and 11.7 Hours

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy (FHI) is a rare disease of infancy with unknown etiology. The disease mainly involves soft tissue, has no specific clinical manifestations, and is difficult to diagnose. At present, the diagnosis is mainly confirmed by histopathological examination, and the main treatment is surgical resection of the pathological tissue, which is prone to recurrence.

A five-month-old female patient was admitted to our hospital with swelling in the right calf. Two biopsies were performed in our hospital and another hospital, respectively, confirming the diagnosis as fibrous hamartoma. After exclusion of surgical contraindications, resection was performed with clear margins of 1 cm. Radiographic examination showed tumor recurrence more than four months after the operation, and surgery was performed again to extend the resection margins to 1.5 cm. The patient is recovering well, and after a follow-up of 36 mo, shows no signs of recurrence.

Our case report demonstrates that FHI should be considered in the differential diagnosis for a lower extremity mass with bone destruction. For FHI with bone destruction and unclear boundaries, excision margins of 1.5 cm could be superior to margins of 1 cm.

Core Tip: Fibrous hamartoma of infancy (FHI) is a rare disease of infancy with unknown etiology. The disease mainly involves soft tissue, has no specific clinical anifestations, and is difficult to diagnose. At present, the diagnosis is mainly confirmed by histopathological examination, and the main treatment is surgical resection of the pathological tissue, which is prone to recurrence. Our case report demonstrates that FHI should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis for a lower extremity mass with bone destruction. For FHI with bone destruction and unclear boundaries, excision margins of 1.5 cm are superior to margins of 1 cm.

- Citation: Qiao YJ, Yang WB, Chang YF, Zhang HQ, Yu XY, Zhou SH, Yang YY, Zhang LD. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy with bone destruction of the tibia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(30): 11190-11197

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i30/11190.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11190

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy (FHI) is a rare disease of infancy and childhood. It is a benign tumor with no obvious tendency for deterioration. Most of these tumors develop by the age of two years, often occurring in the axilla, back and other parts of the trunk, and rarely occurring in the tibia. Generally, accumulating subcutaneous soft tissue and accompanying bone destruction is extremely rare[1-4]. The diagnosis of FHI is mainly confirmed by histopathological examination. Herein, a case of FHI with bone destruction of the tibia is reported.

A five-month-old female patient was found to have swelling of her right calf three months prior to admission.

A five-month-old female patient was found to have swelling of her right calf three months prior to admission. X-ray examination in another hospital showed a tumor of the right tibia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination suggested a space occupying lesions in the upper segment of the right tibia, which were mostly considered to be eosinophilic granulomas. Puncture biopsy in the other hospital revealed a small amount of fibrous hyperplastic tissue without obvious tumor cells.

The child was in good health and had no special disease.

There was no similar case in the patient's family.

Physical examination revealed slight swelling in the anterior aspect of the middle part of the right leg, puncture scar with good local healing, normal tissue local skin temperature, no redness and ulceration of the skin, no local tenderness, and no obvious abnormality.

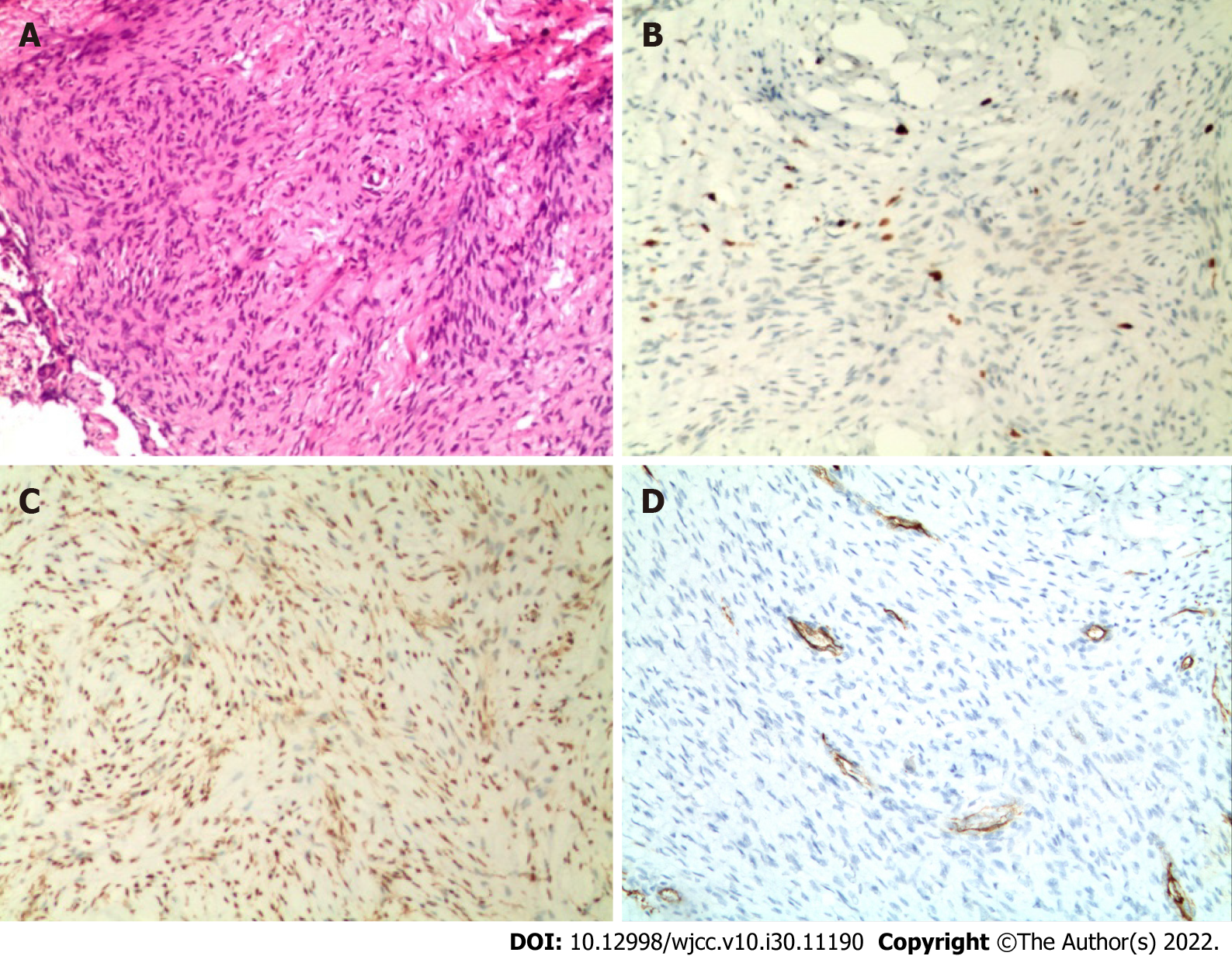

Microscopically, the tumor tissue was staggered in bundles and the cells were fusiform, and the immunohistochemical results included Ki67 (index approximately 5), Desmin (-), S100 (-), smooth muscle actin (SMA) (scattered +), and CD34 (blood vessel +).

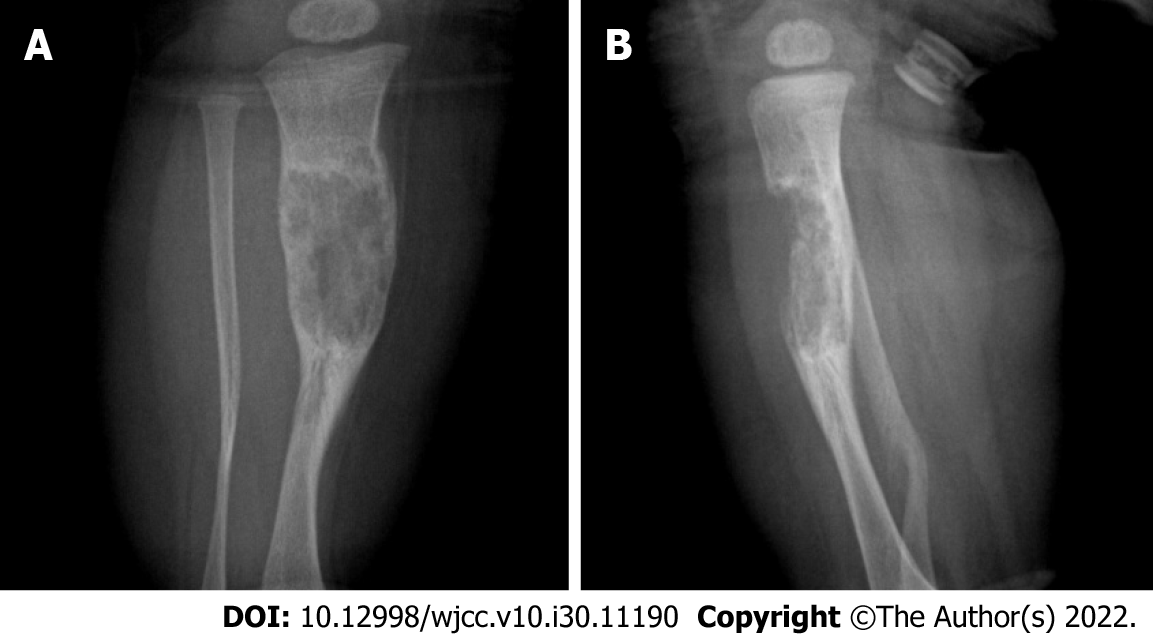

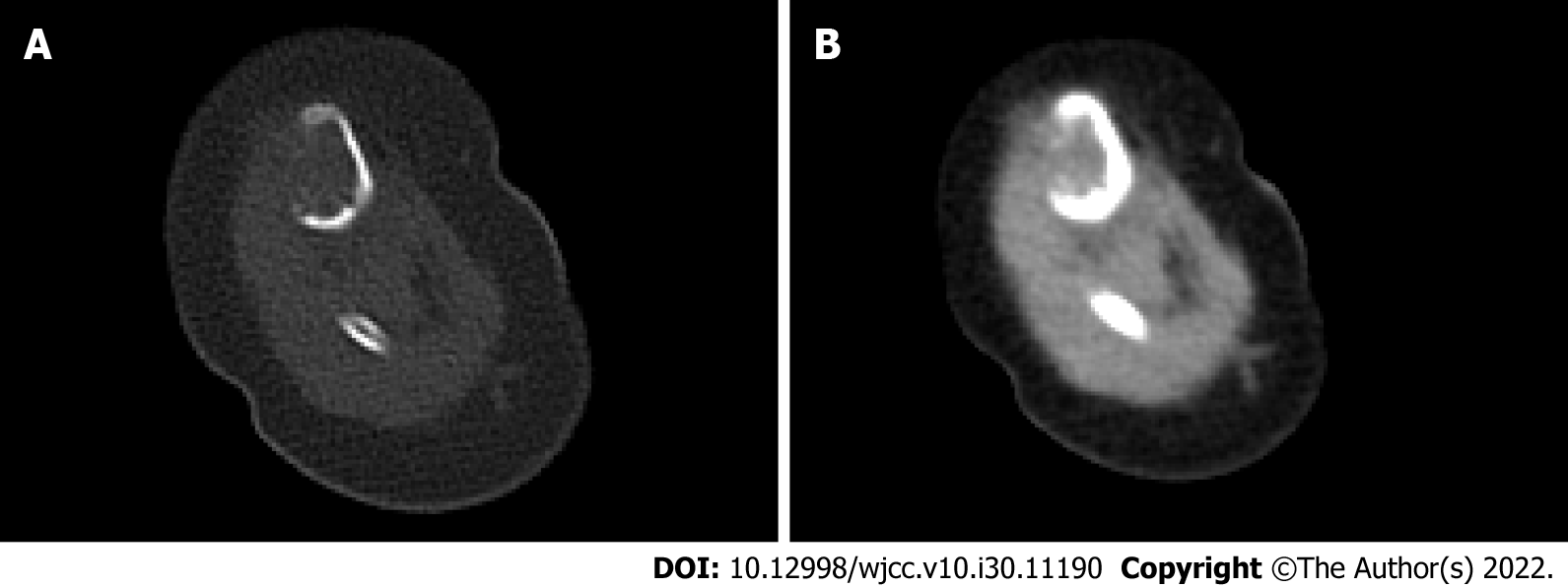

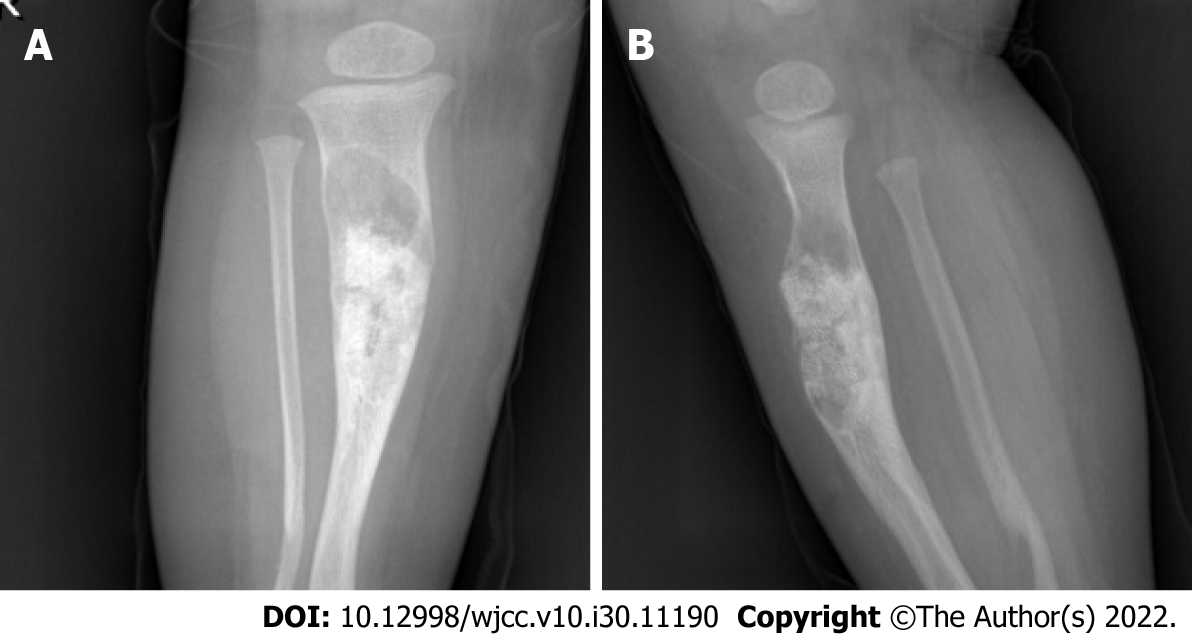

Radiographic examination in our hospital showed an area of bone destruction in the middle part of the right tibia with uneven internal density, unclear boundaries, slightly expansive, approximately 2.7 cm × 1.6 cm in size, and an anterior cortical bone defect (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) examination showed an eccentric, expansive soft tissue density shadow in the middle and upper segments of the right tibia, corresponding bone resorption and destruction, and local cortical bone defect of approximately 2.7 cm × 1.6 cm (Figure 2).

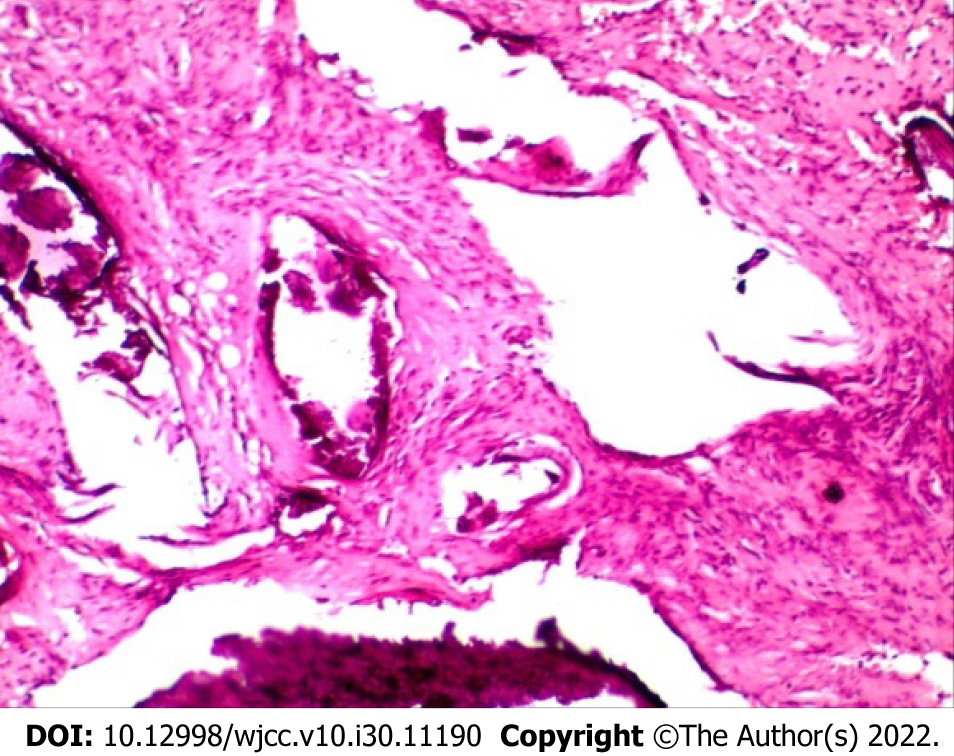

After puncture biopsy, naked eye examination showed a significant amount of gray-white broken tissue with a volume of 1.5 cm × 1 cm × 0.5 cm. Microscopically, the tumor tissue was staggered in bundles and the cells were fusiform (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed Ki67 (index approximately 5), Desmin (-), S100 (-), Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA scattered +), and CD34 (blood vessel +) (Figure 3B-D). Pathological diagnosis was consistent with FHI.

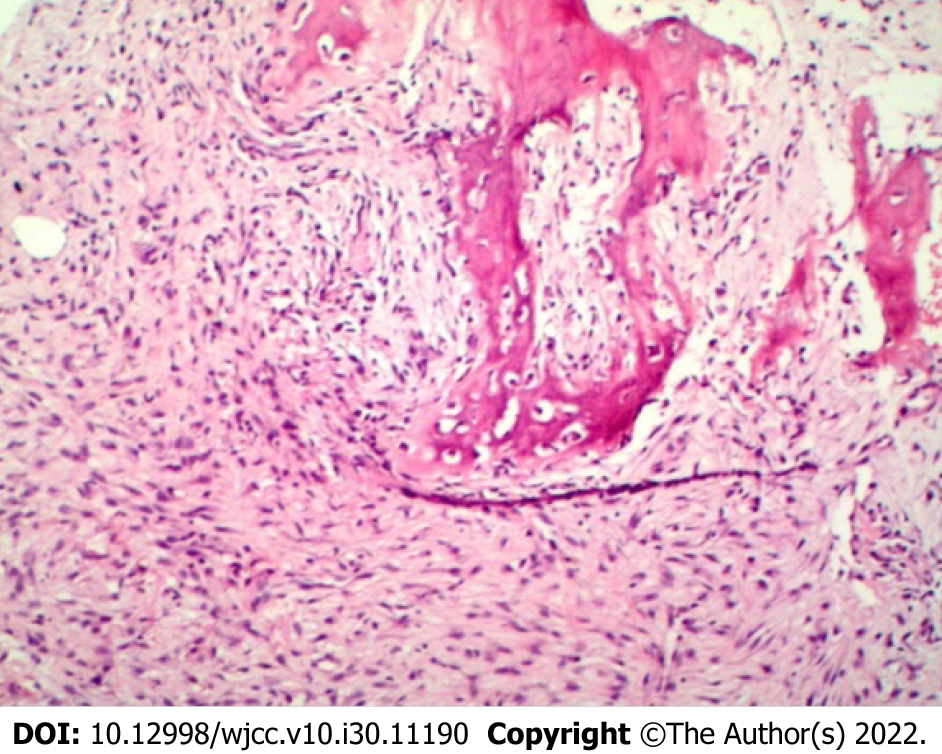

During the first surgical resection under radiographic guidance, a 4.5 cm incision was made at the middle part of the right tibia, which had the maximal swelling, through the puncture biopsy site and traversing the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia. The anterior periosteum of the middle part of the tibia was subsequently explored and cut, revealing destruction and a defect of the anterolateral cortex of the tibia. The bone marrow cavity was filled with granulation tissue and showed fiber-like changes. We abided by the principles of tumor-free resection during the operation. The anterior side of the tibia showed cortical damage of approximately 0.2 cm × 2 cm. The proximal and distal ends of the medullary cavity were closed, and the diseased tissue in the medullary cavity was completely scraped off with a curette followed by the removal of the diseased tissue with 1 cm clear margins. Kirschner wire was inserted through the proximal and distal ends of the medullary cavity and the tumor cavity was repeatedly soaked with distilled water for more than 10 min. Thereafter, the tumor walls were cauterized with an electric knife, wiped three times with anhydrous alcohol, and generously washed with 0.9% saline and diluted iodophor. An appropriate amount of allogeneic bone was implanted in the bone defect, and no obvious active bleeding was observed. A drainage tube was placed, the periosteum was sutured, and wound closure was completed in layers. Postoperative pathological examination revealed that the tumor tissue showed bundle-shaped staggered arrangement and fusiform cells, in which immature bone trabecular components were seen (Figure 4). The pathological diagnosis was a benign fibrous osseous lesion, which was consistent with the results of the previous biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of FHI.

Four months after the initial operation, Radiographic examination showed an increase in the lesion area of the middle and upper segments of the right tibia, and recurrence was suspected (Figure 5). Based on this and the patient's history, clinical signs, and auxiliary examination, reoperation was performed. The scar of the original incision on the right leg was used as a landmark and the current incision was extended to the proximal and distal ends of the tibia along the original incision, lengthening it to approximately 6 cm, and again traversing the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia, which revealed destruction and a defect of the bone cortex of the anterior tibia. The distal bone graft showed adequate healing, but a considerable amount of granulation tissue had to be removed, after which the diseased tissue was resected with clear margins of 1.5 cm. The remaining procedures of the operation were similar to those of the first operation.

After a follow-up of 36 mo, at present, the patient has no obvious abnormality, as reported by the parents during consecutive telephonic follow-up calls. Postoperative pathological examination showed hyperplastic spindle cells with a small amount of bone tissue (Figure 6), and the pathological diagnosis was consistent with FHI.

FHI is a rare superficial benign soft tissue tumor of infants with unclear boundaries. Its pathogenesis and biological characteristics are still unclear. The disease usually occurs in children less than two years of age, of which approximately 23% are born with it, and male to female incidence ratio is approximately 2.4[5]. FHI mostly occurs in the axilla, followed by the upper arm, thigh, back, groin, buttocks, and external genitalia[4-6]. The clinical manifestations include a subcutaneous mass of relatively small volume, but it may occasionally be larger. It is mostly a solitary lesion but may present as multiple lesions, and the number may differ considerably among cases. Occasionally, it may be adherent to the underlying fascia, but invasion of muscle is rare, with destruction of bone being even more rare. Unlike other benign tumors, FHI often shows unclear boundaries. The diagnosis can be made by ultrasonography, CT, MRI, and pathological examination. Ultrasonography findings of FHI mostly include a "snake-like" uneven and increased echogenic mass with unclear boundaries and uneven contour. Color Doppler flow imaging shows no or scattered spotty blood flow signals in the lesion[7], but ultrasonography cannot confirm the diagnosis. CT shows a mixed density mass of fat, soft tissue, and blood vessels, with unclear boundaries, no obvious capsule, and inhomogeneous enhancement[8]. CT examination has limited specificity and can only play an auxiliary role in the diagnosis of FHI. MRI mostly shows mixed signal masses rich in fat, with an interspersed band of beam-like fibrous connective tissue shadow in adipose tissue. Signals of fat and fibrous tissue are characteristic, and the signal of fat inhibition sequence image is high. Enhancement scan shows no enhancement[9]. MRI is of great importance in the diagnosis of FHI due to no radiation exposure, arbitrary axial and multi-parameter imaging characteristics, high tissue resolution, and good hemodynamic analytic ability, and can effectively differentiate benign and malignant lesions with diffusion-weighted imaging[10]. At present, the definitive diagnosis of FHI is by histopathological examination. The tissue composition of FHI is complex and diverse, and is mainly divided into three types: (1) Fibroblasts; (2) primitive mesenchymal cells; and (3) mature adipose tissue. The treatment of FHI is mainly surgical resection, and complete resection with disease free margins is very important to prevent postoperative recurrence.

Our patient was five months of age, which with the range of onset age in most reported cases of FHI. The location of the disease was the anterolateral part of the middle part of the right tibia. At present, there are few detailed reports on FHI of the tibia[1-3,11]. In this patient, the anterolateral cortex of the middle part of the right tibia was destroyed. Detailed reports on bone destruction in FHI are very scarce[1-3,12]. In the presence of a lower limb mass and bone destruction, the possibility of FHI should be considered after considering the patient's symptoms and imaging examinations. The child underwent two puncture biopsies before the resection procedure. For preoperative diagnosis of the disease, we should consider whether it was necessary to perform a repeat biopsy. Based on evaluation of clinical presentation and preoperative imaging examinations, clinicians can determine whether the disease is benign or malignant. If it is considered as benign, surgical treatment can be performed immediately, and postoperative pathological examination can avoid multiple biopsies and surgeries, relieve pain and psychological pressure, relieve economic pressure, and avoid tumor implantation metastasis. The patient’s tumor recurred four months after surgery, and the possible reasons were as follows: FHI was not resected with adequate clear margins, resulting in failure of complete resection during surgery, and repeat biopsies were performed before surgery, destroying the intact capsule of the tumor and resulting in proliferation and seeding of tumor cells to other sites.

Although FHI is a benign tumor, it is infiltrative. Tumor cells can easily enter the adjacent tissue space and infiltrate and destroy the surrounding tissue. To prevent tumor recurrence, intraoperative resection should be expanded. If complete resection is not possible, approximately 15%-16% of patients may have relapse. Therefore, it is recommended to achieve clear surgical margins of at least 1 cm, with the resection depth reaching the level of adjacent normal tissues[1,8]. In this case, although the tumor was resected with clear margins of 1 cm during the first operation, the tumor recurred after surgery. A second operation was performed to resect the tumor with clear margins of 1.5 cm. No obvious abnormality was found during the follow-up period of 36 mo after the second surgery. Thus, the resection scope for FHI complicated by bone destruction may not be the same as that for FHI alone. Currently, there is no unified standard for scope of FHI surgical resection with or without bone destruction[1]. For FHI with ill-defined boundaries and bone destruction, pathological fractures can be avoided by extension of excision.

FHI is a rare benign tumor and diagnosis is often difficult. FHI should be considered in the presence of a lower limb mass with bone destruction. For FHI with bone destruction, resection with clear margins of 1.5 cm may have a better therapeutic effect and a lower recurrence rate. However, individual case studies cannot effectively determine the efficacy of the resection range of ill-defined FHI with bone destruction; therefore, future research should focus on exploring this topic.

Our case report demonstrates that FHI should be considered in the differential diagnosis for a lower extremity mass with bone destruction. For FHI with bone destruction and unclear boundaries, excision margins of 1.5 cm may be superior to margins of 1 cm.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abubakar MS, Nigeria; Arslan M, Turkey S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Seguier-Lipszyc E, Hermann G, Kaplinski C, Lotan G. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:753-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tran AQ, Thuro BA, Albert DM, Lucarelli MJ, Potter HD. Fibrous Hamartoma of Infancy in the Eyelid: A Rare Presentation. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32:e150-e151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Al-Ibraheemi A, Martinez A, Weiss SW, Kozakewich HP, Perez-Atayde AR, Tran H, Parham DM, Sukov WR, Fritchie KJ, Folpe AL. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a clinicopathologic study of 145 cases, including 2 with sarcomatous features. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:474-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sforza-Huffman C. Cytology of fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a helpful approach for an uncommon soft tissue lesion. Acta Cytol. 2008;52:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Melnick L, Berger EM, Elenitsas R, Chachkin S, Treat JR. Fibrous Hamartoma of Infancy: A Firm Plaque Presenting with Hypertrichosis and Hyperhidrosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:533-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yu G, Wang Y, Wang G, Zhang D, Sun Y. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a clinical pathological analysis of seventeen cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3374-3377. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lee S, Choi YH, Cheon JE, Kim MJ, Lee MJ, Koh MJ. Ultrasonographic features of fibrous hamartoma of infancy. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:649-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Saab ST, McClain CM, Coffin CM. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a clinicopathologic analysis of 60 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:394-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stensby JD, Conces MR, Nacey NC. Benign fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a case of MR imaging paralleling histologic findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:1639-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee SY, Jee WH, Jung JY, Park MY, Kim SK, Jung CK, Chung YG. Differentiation of malignant from benign soft tissue tumours: use of additive qualitative and quantitative diffusion-weighted MR imaging to standard MR imaging at 3.0 T. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:743-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang S, Ma Q, Ying H, Jiao Q, Yang D, Zhang B, Zhao L. Giant fibrous hamartoma of infancy: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e19489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vilela VM, Ribeiro VM, Paiva JC, Pires DD, Santos LS. Clinical and radiological characterization of fibrous hamartoma of infancy. Radiol Bras. 2017;50:204-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |