Published online Oct 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11178

Peer-review started: July 15, 2022

First decision: August 22, 2022

Revised: August 29, 2022

Accepted: September 22, 2022

Article in press: September 22, 2022

Published online: October 26, 2022

Processing time: 97 Days and 12.5 Hours

The management of dural tears is important. While a massive dura can be repaired with absorbable suture lines, cerebrospinal fluid leakage can be attenuated by dural sealant when an unintended tiny durotomy occurs intraoperatively. DuraSeal is often used because it can expand to seal tears. This case emphasizes the need for caution when DuraSeal is used as high expansion can cause complications following microlaminectomy.

A 77-year-old woman presented with L2/3 and L3/4 lateral recess stenosis. She underwent microlaminectomy, foraminal decompression, and disk height restoration using an IntraSPINE® device. A tiny incident durotomy occurred intraoperatively and was sealed using DuraSealTM. However, decreased muscle power, urinary incontinence, and absence of anal reflexes were observed postoperatively. Emergent magnetic resonance imaging revealed fluid collection causing thecal sac indentation and central canal compression. Surgical exploration revealed that the gel-like DuraSeal had entrapped the hematoma and, conse

DuraSeal expansion must not be underestimated. Changes in neurological status require investigation for cauda equina syndrome due to expansion.

Core Tip: The number of laminectomies is increasing, and incidental durotomy sometimes occurs intraoperatively. One of the approaches to manage dural tears was using sealants such as DuraSealTM. We present the case of a 77-year-old patient who suffered from incidental durotomy with treatment of using DuraSealTM when undergoing spine surgery. Postoperative cauda equina syndrome was noted. Surgical exploration revealed thecal sac and nerve roots compression by entrapped hematoma. Our case highlights the potential catastrophic consequences of over-expansion of dural sealant, and demonstrates that cauda equina syndrome should be considered if neurological symptoms develop following application of DuraSealTM.

- Citation: Yeh KL, Wu SH, Fuh CS, Huang YH, Chen CS, Wu SS. Cauda equina syndrome caused by the application of DuraSealTM in a microlaminectomy surgery: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(30): 11178-11184

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i30/11178.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i30.11178

As life expectancy increases worldwide, degenerative diseases of the lumbosacral spine are becoming more common[1]. Debilitating conditions are currently the major causes of morbidity, disability, and lost productivity[2,3]. The current treatment of choice for spine degeneration is laminectomy for nerve root decompression. In laminectomy, managing intraoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage is important because it increases the risk of sequelae such as meningitis or abscesses, as well as the late development of pseudomeningocele[4,5].

When incidental durotomy occurs intraoperatively and causes CSF leakage, primary dural closure is not always feasible or may not be watertight[6,7]. An alternative solution is the use of a polyethylene glycol hydrogel dural sealant, DuraSealTM. This sealant comprises PEG ester and trilysine amine solutions. When these two solutions are mixed, a reaction occurs and covers the ruptured dura. The mixed solution expands and forms a watertight layer, providing sufficient time for the dura to adequately heal following this application. However, this expansion may also be associated with the development of cauda equina syndrome (CES). Here, we report a case of CES occurring following dural closure and consequent compromised neurological function due to DuraSealTM expansion in the spinal canal.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shin-Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital (202020708R).

A 77-year-old woman with an underlying condition of hypertension for over 15 years who had undergone bilateral cataract surgery 10 years ago presented to the orthopedic outpatient department of our institute with progressive radicular pain, chronic lumbalgia, and right thigh pain. She complained of neurological claudication that had lasted for over five years.

The patient presented to the orthopedic outpatient department of our institute with progressive radicular pain, chronic lumbalgia, and right thigh pain. She complained of neurological claudication that had lasted for over five years.

She had hypertension for over 15 years, and had undergone bilateral cataract surgery 10 years ago.

Her family history was unremarkable.

Conservative treatments, such as physiotherapy, administration of muscle relaxants, shockwave treatment, and oral medications including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, local anesthetic, and steroid injection over the past year had not alleviated the symptoms. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to evaluate disease severity in our hospital.

She did not receive laboratory examinations which related to her spine lesions.

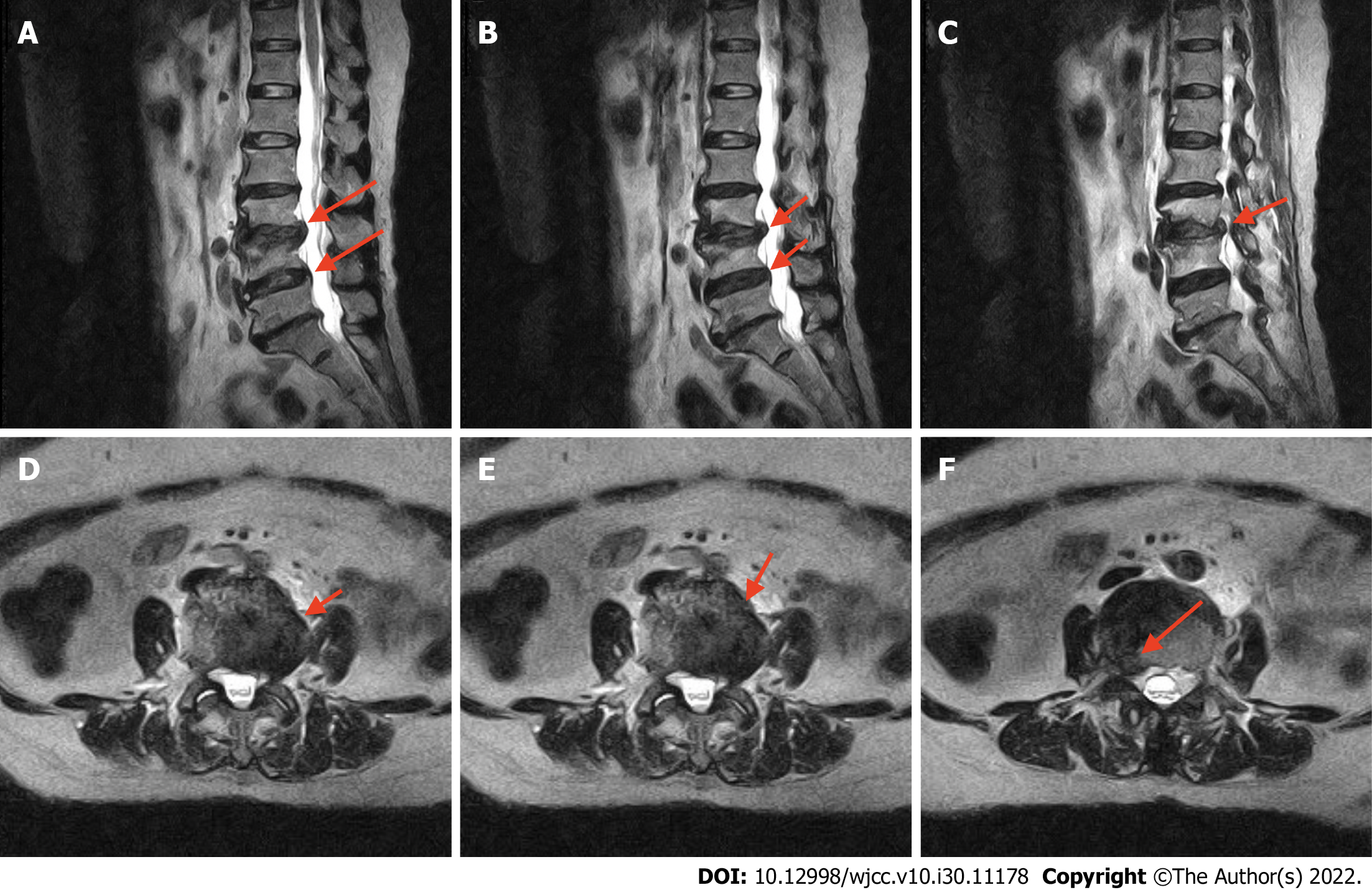

T2-weighted MRI (Figure 1) revealed collapsed disc height at the L2-3 and L3-4 Levels and a bulging disk compressing the thecal sac and right neural foramen, causing bilateral lateral recess stenosis and neuroforaminal narrowing, especially on the right side, abutting the L3 and L4 nerve roots.

Based on these imaging findings, lumbar stenosis at the L2/3 and L3/4 Levels was diagnosed, accompanied by neurological symptoms.

Surgical treatment was suggested and the severity of the disease, risks of surgery, and alternative treatments were discussed with the patient. Microlaminectomy and ossified ligamentum flavum removal followed by foraminotomy were planned; therefore, the traversing and exiting neural structures were free of compression. After adequate microlaminectomy, IntraSPINE®, an interlaminar dynamic spacer, was implanted between the L2-3 and L3-4 Levels of the interlaminar space to restore the disc height.

Microlaminectomy for foraminal decompression was performed at the L2/3 and L3/4 Levels. During microlaminectomy, a tiny unintended durotomy occurred, and CSF leakage was observed during decompressive microlaminectomy via an extradural spinal approach. To seal the CSF leakage, we covered the dural defect with oxidized regenerated cellulose, Surgicel, followed by DuraSealTM (around 2 cc) and a final layer of dry Gelfoam (Pharmacia & Upjohn) before securing hemostasis. This step has been widely used in our past surgical experience in cases of incidental durotomy. After completing lumbar decompression, sealing the dura tear, and implanting the IntraSPINE®, a hemovac was used for blood drainage and the wound was closed.

The patient had no neurological discomfort one day after surgery; however, the following day, bilateral lower-extremity numbness and weakness occurred. The Medical Research Council (MRC) scale of muscle power decreased from 5 to 2 (5: Normal muscle power, 2: Active movement with gravity eliminated) on the distal muscles in the bilateral lower extremities and deteriorated gradually[8]. We attempted to remove urine from the Foley tube, but urinary retention was observed. The residual urine volume was > 200 cc. In addition, the bulbocavernosus and anal reflexes were absent. The neurological dysfunction might not have been related to the intraoperative decompression and disk height restoration using an IntraSPINE® device because the symptoms did not appear immediately but rather 2 days after the surgery. Based on these observations, CES was suspected.

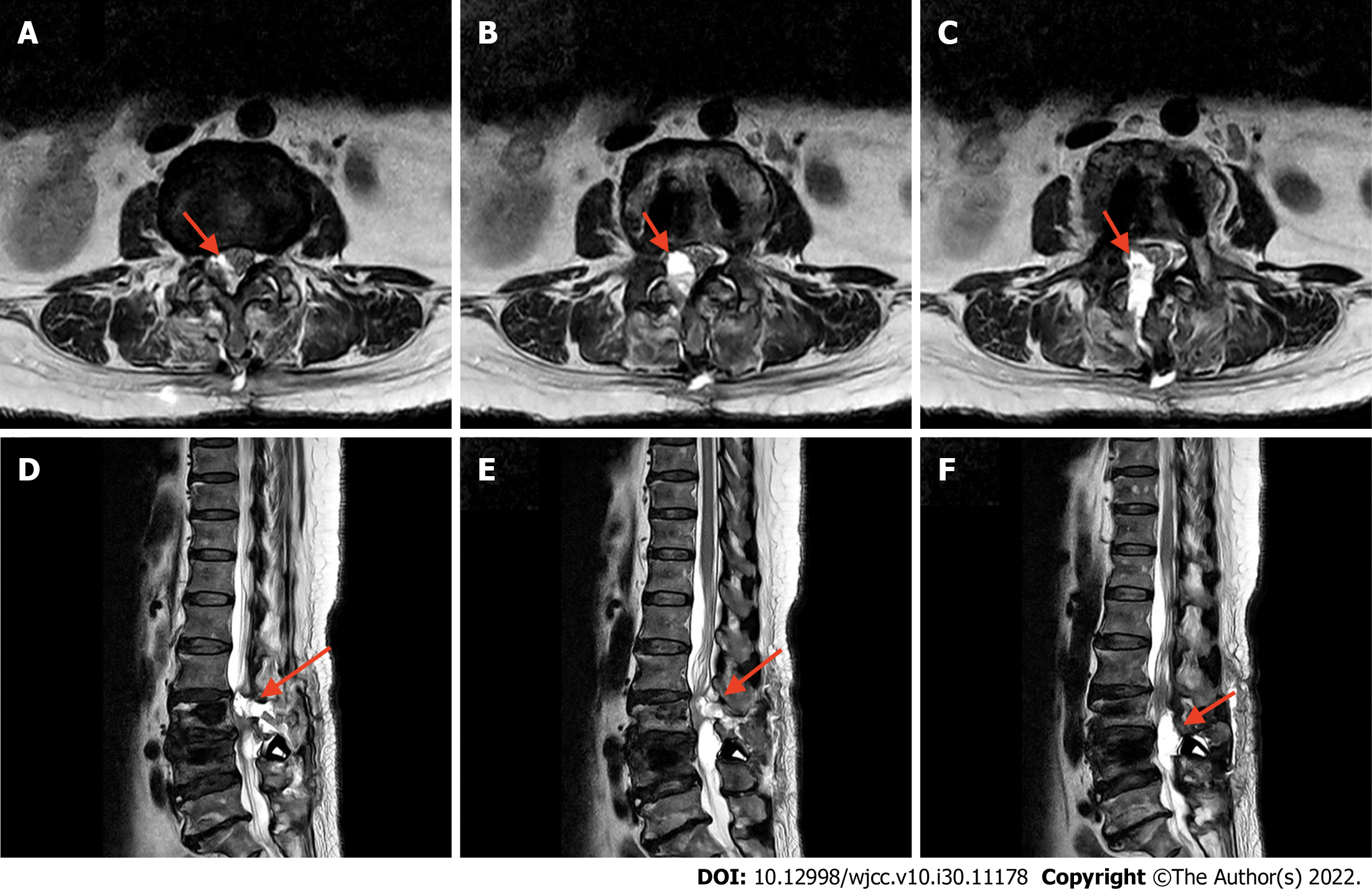

An emergent T2-weighted phase MRI examination revealed regional fluid collection at the surgical bed, protruding anteriorly at the junction of L2 and L3 to L4 Levels. This fluid caused thecal sac indentation and narrowing of the central canal (Figure 2). Therefore, emergent exploration and decompression of the thecal sac were performed. Intraoperatively, a large amount of gel-like DuraSealTM had formed a layer around the thecal sac and entrapped the extradural hematoma, resulting in spinal cord compression. We removed all DuraSealTM, exposing the bilateral L3 and L4 nerve roots, and ensured that no DuraSealTM material was compressing the nerve roots (Figure 3).

Unfortunately, although the patient was undergoing rehabilitation and physical therapy was initiated, muscle power and urinary and stool incontinence persisted for four months postoperatively. Her American Spinal Injury Association score was A.

Intraoperative incident durotomy is one of the most common complications of spinal surgery, especially revision surgery. This adverse event is always related to CSF leakage from the subarachnoid space via dural defects[9]. The incidence of incident durotomy ranges from 0.1% to 15.9%, depending on the difficulty of spinal surgery[9,10]. Despite the fairly low incidence, the risks and associated costs of these adverse incidents cannot be ignored[11]. Longer admission lengths, higher postoperative infection rates, and lower postoperative satisfaction were also noted in these patient groups.

If the CSF leakage is not sealed, further complications can develop, including nausea, vomiting, vertigo, tinnitus, postural headache, meningitis, and fistula formation[12]. The methods to control CSF leakage include direct dural repair. This can be achieved using an absorbable suture line or by grafting fat, muscle, or fascia to the tear[13,14]. However, direct repair may not be an ideal or feasible solution depending on the position of the tear[15]. DuraSealTM provides a useful alternative treatment for dural tears because the material can expand to reduce CSF leakage[16]. Furthermore, the non-toxicity, bioabsorbability, and accessibility of this material have led to its widespread use[17]. DuraSealTM can swell by up to 50%, reaching peak expansion within 3-14 d, and persisting for approximately four weeks[18].

Our study is not the first to report neurological complications associated with DuraSealTM use. The first reported case was that of a 13-year-old girl who underwent cervical decompression and fusion for Chiari malformation in 2007[19]. In 2009, a case of postoperative cauda equina compression syndrome caused by the use of DuraSealTM before spinal decompression surgery was reported[15]. Similarly, DuraSealTM-related CES was reported after total laminectomy and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in 2012[16]. All these cases involved nerve compression due to DuraSealTM expansion.

Currently, microlaminectomy is preferred over traditional laminectomy for decompression to reduce the breakdown of bony structures and blood loss, as well as the length of hospital stay and healthcare costs[20]. However, microlaminectomy reduces the extradural space more than total laminectomy, with a consequent increase in the possible mass effects. Applying an expandable agent such as DuraSealTM dramatically increases the risk of CES compared to total laminectomy alone because the small extradural space provides limited space for DuraSealTM expansion. Furthermore, it is difficult to predict the nature of the expanding material in the epidural space, with potentially serious consequences.

It is important to achieve adequate hemostasis before dural closure. DuraSealTM is a self-polymerizing agent that can rapidly produce a watertight hydrogel layer over the dural surface. If hemostasis is not under control before applying DuraSealTM, the hematoma can be entrapped, contributing to the development of complications[6].

There have been several reports of neurological complications following the intraspinal application of absorbable gelatin sponges, such as Gelfoam, or oxidized cellulose products, such as Surgicel, a loosely woven fabric of cellulose[21,22]. In 2015, a CES case was reported to have been caused by the application of Surgicel after lumbar microdiscectomy and foraminal decompression[23,24]. Thus, except for DuraSealTM, excess intraspinal sealants should be removed when hemostasis is achieved[25].

The present case highlighted that the potential postoperative expansion of DuraSealTM should never be underestimated when this product is used in locations sensitive to compression, such as microlaminectomy. The publication of this case will raise awareness of the possibility of DuraSealTM expansion and the concomitant, potentially irreversible, postoperative complications.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu JY, United States; Xu BS, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Zhu C, Wang LN, Chen TY, Mao LL, Yang X, Feng GJ, Liu LM, Song YM. Sequential sagittal alignment changes in the cervical spine after occipitocervical fusion. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:1172-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alvarez JA, Hardy RH Jr. Lumbar spine stenosis: a common cause of back and leg pain. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:1825-1834, 1839. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Yeung KH, Man GCW, Deng M, Lam TP, Cheng JCY, Chan KC, Chu WCW. Morphological changes of Intervertebral Disc detectable by T2-weighted MRI and its correlation with curve severity in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23:655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Black P. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks following spinal surgery: use of fat grafts for prevention and repair. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:250-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hawk MW, Kim KD. Review of spinal pseudomeningoceles and cerebrospinal fluid fistulas. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim KD, Ramanathan D, Highsmith J, Lavelle W, Gerszten P, Vale F, Wright N. DuraSeal Exact Is a Safe Adjunctive Treatment for Durotomy in Spine: Postapproval Study. Global Spine J. 2019;9:272-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jesse CM, Schermann H, Goldberg J, Gallus M, Häni L, Raabe A, Schär RT. Risk Factors for Postoperative Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage After Intradural Spine Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2022;164:e1190-e1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | John J. Grading of muscle power: comparison of MRC and analogue scales by physiotherapists. Medical Research Council. Int J Rehabil Res. 1984;7:173-181. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Grannum S, Patel MS, Attar F, Newey M. Dural tears in primary decompressive lumbar surgery. Is primary repair necessary for a good outcome? Eur Spine J. 2014;23:904-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Khan MH, Rihn J, Steele G, Davis R, Donaldson WF 3rd, Kang JD, Lee JY. Postoperative management protocol for incidental dural tears during degenerative lumbar spine surgery: a review of 3,183 consecutive degenerative lumbar cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2609-2613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Grotenhuis JA. Costs of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage: 1-year, retrospective analysis of 412 consecutive nontrauma cases. Surg Neurol. 2005;64:490-493, discussion 493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Raskin NH. Lumbar puncture headache: a review. Headache. 1990;30:197-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Di Vitantonio H, De Paulis D, Del Maestro M, Ricci A, Dechordi SR, Marzi S, Millimaggi DF, Galzio RJ. Dural repair using autologous fat: Our experience and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2016;7:S463-S468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hodges SD, Humphreys SC, Eck JC, Covington LA. Management of incidental durotomy without mandatory bed rest. A retrospective review of 20 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:2062-2064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mulder M, Crosier J, Dunn R. Cauda equina compression by hydrogel dural sealant after a laminotomy and discectomy: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:E144-E148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Neuman BJ, Radcliff K, Rihn J. Cauda equina syndrome after a TLIF resulting from postoperative expansion of a hydrogel dural sealant. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1640-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Boogaarts JD, Grotenhuis JA, Bartels RH, Beems T. Use of a novel absorbable hydrogel for augmentation of dural repair: results of a preliminary clinical study. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:146-51; discussion 146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kacher DF, Frerichs K, Pettit J, Campbell PK, Meunch T, Norbash AM. DuraSeal magnetic resonance and computed tomography imaging: evaluation in a canine craniotomy model. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:ONS140-7; discussion ONS140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Blackburn SL, Smyth MD. Hydrogel-induced cervicomedullary compression after posterior fossa decompression for Chiari malformation. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:302-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lundberg J, Langevin JP. Lumbar Microlaminectomy vs Traditional Laminectomy. Fed Pract. 2017;34:32-35. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Bellen P. [Prevention of peridural fibrosis following laminectomy. Apropos of a case of monoradicular paralysis due to an intracanalar hematoma on Gelfoam]. Acta Orthop Belg. 1992;58:236-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Brodbelt AR, Miles JB, Foy PM, Broome JC. Intraspinal oxidised cellulose (Surgicel) causing delayed paraplegia after thoracotomy--a report of three cases. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84:97-99. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Bessette MC, Mesfin A. Cauda equina syndrome caused by retained hemostatic agents. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1518-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Frati A, Thomassin-Naggara I, Bazot M, Daraï E, Rouzier R, Chéreau E. Accuracy of diagnosis on CT scan of Surgicel® Fibrillar: results of a prospective blind reading study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;169:397-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee G, Lee CK, Bynevelt M. DuraSeal-hematoma: concealed hematoma causing spinal cord compression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E1522-E1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |