Published online Oct 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i29.10565

Peer-review started: November 4, 2021

First decision: March 7, 2022

Revised: March 20, 2022

Accepted: August 30, 2022

Article in press: August 30, 2022

Published online: October 16, 2022

Processing time: 329 Days and 0.3 Hours

Listeria is a food-borne disease, which is rarely prevalent in the normal popu

A 75-year-old man presented with a fever for 1 wk and was admitted to the hospital for diagnosis and management of a lung infection. His condition improved after receiving anti-infective treatment for 2 wk. However, soon after he was discharged from the hospital, he developed fever again, and gradually developed various neurological symptoms, impaired consciousness, and stiff neck. Thereafter, through the cerebrospinal fluid metagenomic testing and blood culture, the patient was diagnosed with Listeria monocytogenes meningitis and sepsis. The patient died after being given active treatment, which included penicillin application and invasive respiratory support.

This case highlights the ultimate importance of early identification and timely application of the various sensitive antibiotics, such as penicillin, vancomycin, meropenem, etc. Therefore, for high-risk populations with unknown causes of fever, multiple blood cultures, timely cerebrospinal fluid examination, and metagenomic detection technology can assist in confirming the diagnosis quickly, thereby guiding the proper application of antibiotics and improving the prognosis.

Core Tip: Listeria is a considered a food-borne disease but is rarely prevalent in the normal population. We present herein, a rare case of meningoencephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) that evolved in a previously healthy immunocompetent old male patient. Both the cerebrospinal fluid metagenomic test and bilateral blood culture test results suggested the occurrence of L. monocytogenes. The findings of this case highlight the ultimate importance of early identification and timely application of sensitive antibiotics. Therefore, for high-risk populations with unknown causes of fever, multiple blood cultures, timely cerebrospinal fluid examination, and metagenomic detection technology can assist in confirming the diagnosis quickly, which can facilitate the application of suitable antibiotics and significantly improve the prognosis.

- Citation: Wu GX, Zhou JY, Hong WJ, Huang J, Yan SQ. Treatment failure in a patient infected with Listeria sepsis combined with latent meningitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(29): 10565-10574

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i29/10565.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i29.10565

Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) is a gram-positive facultative intracellular bacteria. It can be spread to the humans through the ingestion of contaminated foods, especially ready-to-eat foods, products with a longer shelf life, cooked foods, and soft cheeses[1-3]. It predominantly affects pregnant women, newborns, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients[3-5]. The morbidity rate is estimated to be about 3-6 cases per million per year, and the mortality rate is approximately 27%[6]. The most common forms of infections include listeriosis of the nervous system, bacteremia, and the vertical transmission from the mother to child[2]. Moreover, infections caused during pregnancy can contribute to miscarriage, premature delivery, and amnionitis, while neonatal infections can lead to delayed meningitis, conjunctivitis, and pneumonia. Additionally, in immunodeficiency patients, Listeria can also easily cause central nervous system infection, endocarditis, and sepsis[7]. The clinical symptoms of Listeria meningitis are similar to meningoencephalitis caused by other bacterium, but the prodromal period is relatively long, the repeated detection rate of the traditional tests is low, and the first-line treatment with the third-generation cephalosporins is often ineffective[8]. Therefore, it is especially important to diagnose the disease as early as possible so that an appropriate treatment can be initiated, and the best clinical outcome can be achieved in infected patients, especially immunocompromised elderly patients.

A 75-year-old male was suffering from fever for 1 wk, as a result of which the patient was admitted to the Department of Infectious Diseases on May the 18th, 2020.

The highest body temperature recorded was 39.0 °C, and it was accompanied by chills, dizziness during the fever, and remission after fever. The patient suffered from no headache, abdominal pain, or diarrhea, and sputum, nasal congestion, or runny nose was not evident.

He had a history of hypertension.

No special personal or family history was reported.

The patient’s temperature was 39 °C, heart rate was 98 bpm, respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 139/75 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room air was 98%. The breath sounds in both the lungs were clear, heart rhythm was uniform, and the neurological tests were negative.

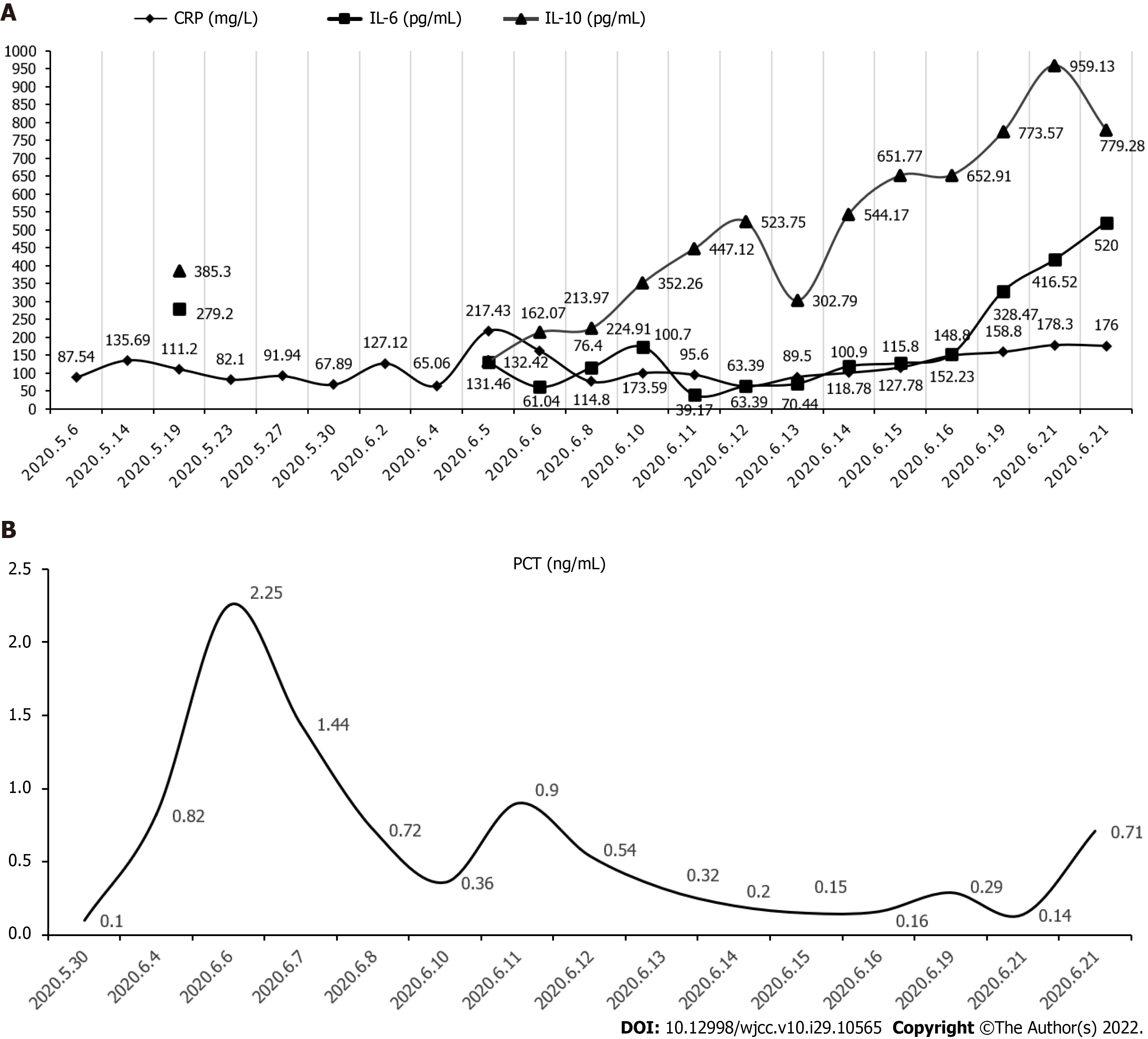

A number of routine blood and biochemical tests were conducted which showed the following values: white blood cell count 7.1 × 109/L, neutrophils 58.6%, monocytes 24.4%, hemoglobin 83 g/L, C-reactive protein (CRP) 111.20 mg/L, cell factor interleukin (IL)-6: 279.22 pg/mL↑, cell factor IL-10 3653.30 pg/mL↑, plasma procalcitonin 0.19 ng/mL, blood amyloid A 509.5 mg/L↑, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 71 mm/L, lactate dehydrogenase 694 U/L↑, creatine kinase 19 U/L↓, albumin 27 g/L↓, K+ 2.99 mmol/L↓, Na+ 135.1 mmol/L↓, Cl- 98.5 mmol/L↓, calcium 1.87 mmol/L↓, phosphorus 0.65 mmol/L↓, but creatinine level was found to be normal. The patient’s anti-nuclear antibody, titer 1:100, anti-SSA-, and anti-SCL70 positive. The patient’s TORCH test (Toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalo, and herpes viruses), Plasmodium test, fungal D-glucan test, coronavirus disease 2019, hemorrhagic fever IgM antibody, Widder test, and Weil Felix reaction results were all noted to be normal. Bilateral blood culture test results suggested the occurrence of "L. monocytogenes". To complete the lumbar puncture, the routine result of cerebrospinal fluid was as follows: "nucleated cell count 420 × 106/L (reference range is less than 8 × 106/L), lymphocyte 75%", cerebrospinal fluid biochemical "lactate dehydrogenase 472 U/L" (Reference range 8-32 U/L), total protein 261.3 mg/dL (reference range 15.0-45.0 mg/dL), glucose 1.51 mmol/L (reference range 2.5-4.5 mmmol/L), chloride content (Cl-) 111.0 mmol/l (reference range 120.0-130.0 mmol/L)", cerebrospinal fluid adenosine deaminase 16 U/L (normal), cerebrospinal fluid cryptococcal smear and cryptococcal capsular antigen test were all found to be negative, but the cerebrospinal fluid culture was observed to be negative. Cerebrospinal fluid metagenomic test results indicated the presence of "G+ bacteria, L. monocytogenes, and the relative abundance was 2.14%". In addition, the suspected background bacteria "G+ bacteria, was Staphylococcus aureus, and the relative abundance was 0.43%" were also detected. The results of CRP, IL-6, IL-10, and PCT during the patient's hospitalization have been shown in Figure 1.

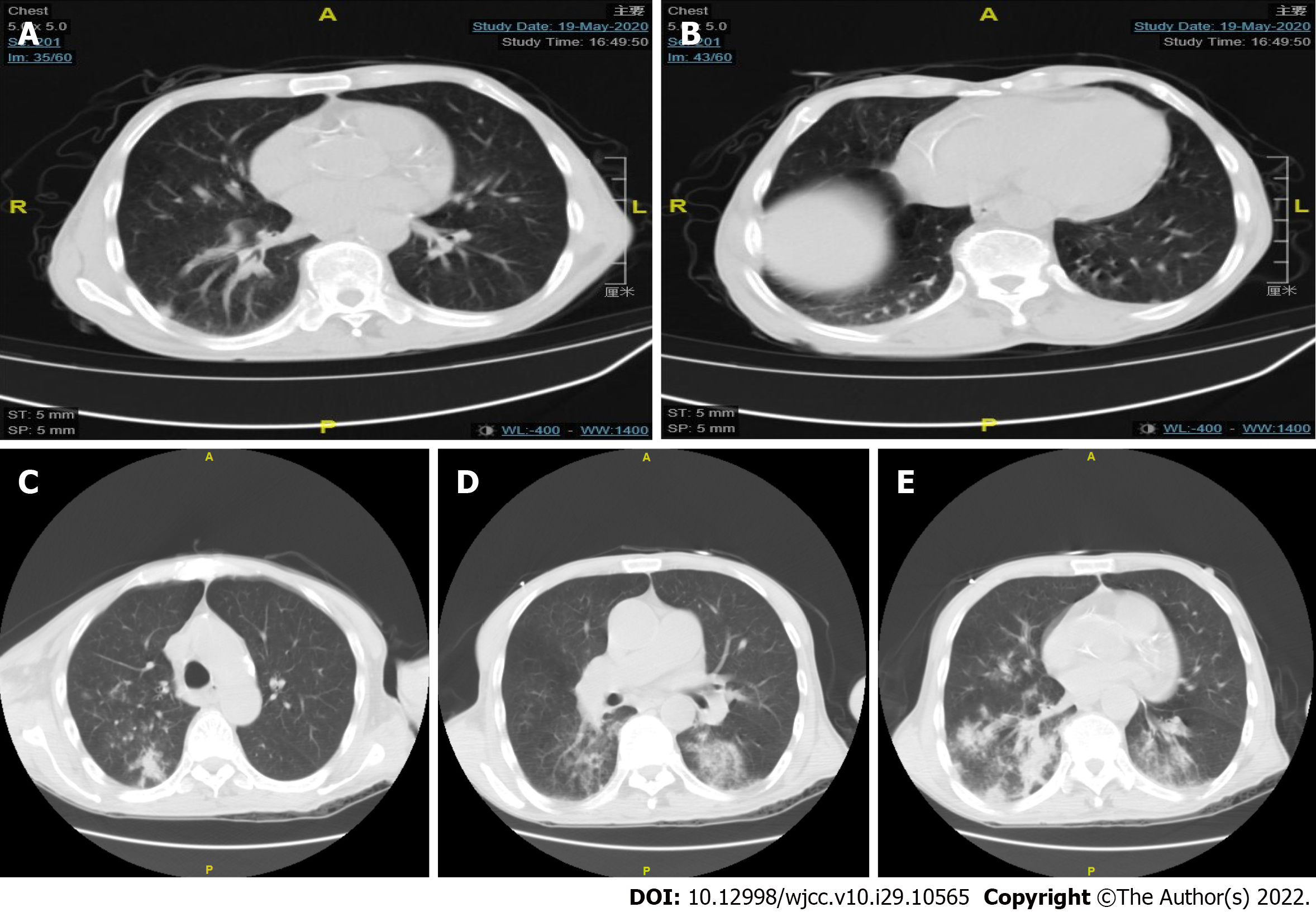

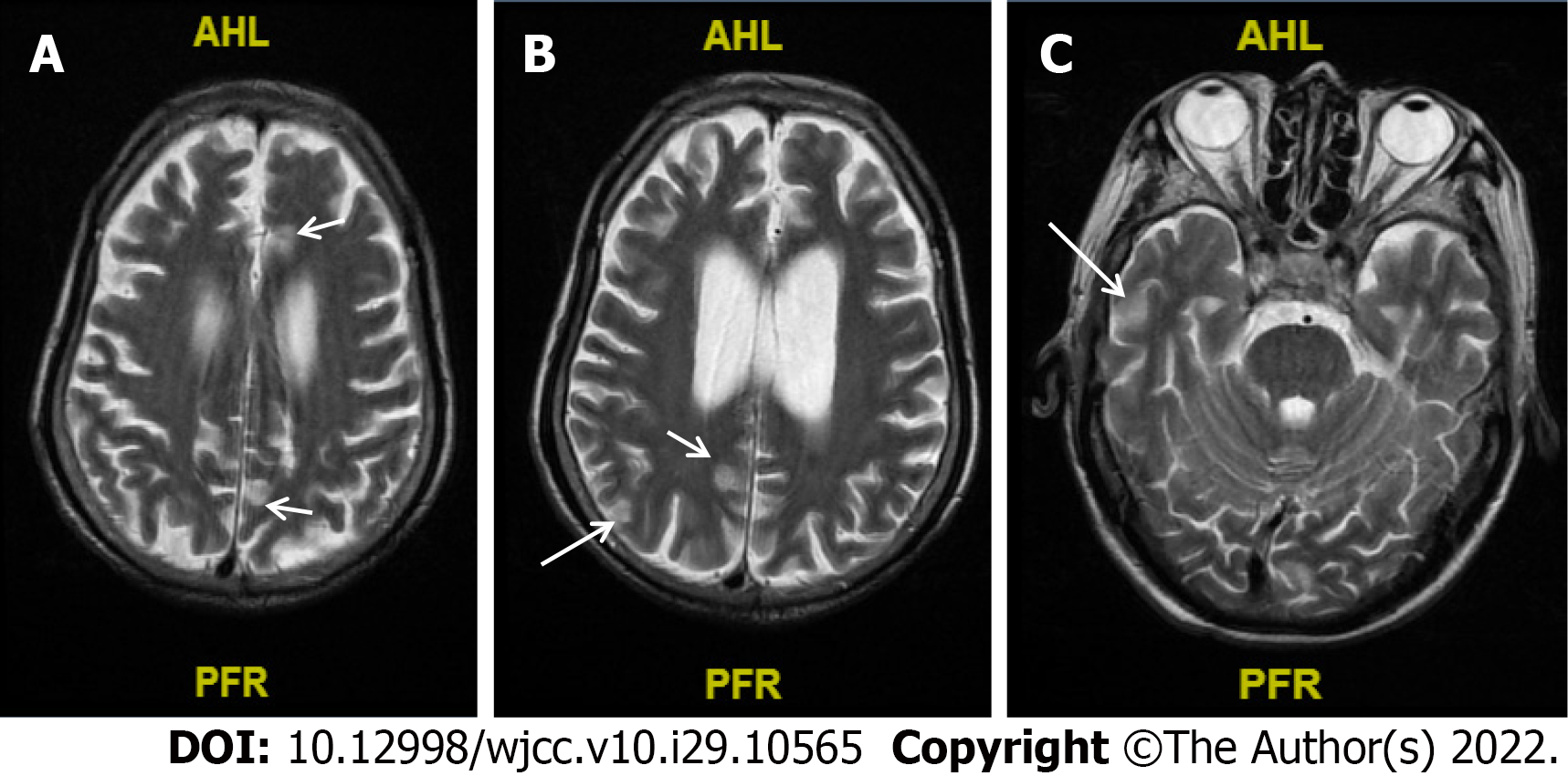

The chest computed tomography (CT) results of the patient revealed a small amount of effusion in the pleural cavities on both the sides, and nodules were distinctly visible in the pleura and under the pleura (Figure 2A and B). However, no obvious abnormalities were found in cranial computed tomography. After two weeks treatment, CT of the patient’s chest displayed multiple nodules in both lungs (similar to the previous), scattered patchy shadows in both the lungs, and possible infection; in addition, the patient had a small amount of pleural effusion (found to be decreased) in both lungs (Figure 2C-E). The results of cranial MR plain scan + water suppression + diffusion-weighted diffusion weighted imaging showed that abnormal signals were scattered in the sub-frontal cortex, midbrain, and posterior horns of both the sides of the ventricle, whereas the lacunar foci were found to be scattered under the frontal cortex on both the sides, and transparent interstitial space was formed (Figure 3).

The patient's diagnosis was finally considered to be sepsis, lung infection, respiratory failure, electrolyte imbalance: hyponatremia, hypokalemia, autoimmune disease and Listeria monocytic meningoencephalitis.

The patient was hence administered levofloxacin 0.5 g qd intravenously for 3 d, the body temperature did not drop significantly, and the highest body temperature was still observed to be above 39.0 °C. The blood culture indicated the presence of a penicillin-resistant "Staphylococcus capital subspecies". According to the drug susceptibility results, the antibiotic treatment was changed to "Vancomycin injection 500000 U q6h" intravenous infusion for anti-infection treatment. During this period, the patient's body temperature reached the normal levels. Vancomycin was used for 6 d, and the body temperature was maintained at the normal level for more than 3 d, after which the drug was stopped, and the patient was discharged from the hospital after relief was noted in the various symptoms. One day after being discharged from the hospital, the patient developed high fever again, with a maximum body temperature of 39.7 °C. The fever was also accompanied by chills, cough, and sputum, and the sputum was rather thick and difficult to cough up. There was no discomfort noted such as chest pain, and no limb twitching was found. During the physical examination, the patient’s pupils were sluggish in the light reflection, appeared confused, mentally soft, and could only communicate briefly, the muscle strength test could not cooperate, but voluntary activities were seen. The patient also suffered from diarrhea.

The patient was hospitalized in the emergency intensive care unit (ICU) and was given high-frequency oxygen inhalation. The patient was administered an anti-infective and anti-inflammatory treatment of piperacillin and tazobactam 4.5 g q8h intravenously and a 40 mg methylprednisolone injection. The patient still suffered from the repeated fever, and his body temperature was above 38.3 °C. Considering that atypical bacterial infections were not covered, he was also given an intravenous infusion of levofloxacin 0.5 g qd as an anti-infective treatment, and thereafter his body temperature returned to normal and his consciousness became clear. The patient's CRP dropped to 76.4 mmol/L and was thereafter transferred to the general ward of the Department of Respiratory Medicine for further treatment.

On the day of the transfer to the Department of Respiratory Medicine, atrial fibrillation occurred suddenly, and he displayed unresponsiveness, slurred speech, and shortness of breath under nasal cannula oxygen inhalation. Upon physical examination, the patient displayed slow light reflexes, stiff neck, increased muscle tone, and wet rales in both lungs.

The patient’s condition was critically severe, with repeated fever with the body temperature fluctuating around 38.7 °C and sudden blood pressure drops, as well as signs of septic shock. Hence, active rehydration and a norepinephrine micropump was used to maintain blood pressure. For the bacterial encephalitis, antibiotics were adjusted to 1 million units of vancomycin injection q12h combined with meropenem injection 1.0 g q8h and he was again transferred to ICU for the continuous treatment. At the same time, the methylprednisolone was first reduced to 20 mg and thereafter it was completely stopped. However, in the early morning of the 6th day after returning to the ICU, the patient suddenly became unconscious, the base of the tongue fell back, and he suffered from shortness of breath, stiff neck, and tremor of the limbs, and his heart rate dropped to 40 beats per minute. The patient's trachea was observed to be intubated, and breathing was assisted by a ventilator. After this, the patient's condition continued to deteriorate rapidly, with symptoms of repeated high fever, septic shock, and multiple organ failure, accompanied by a gradual decrease in consciousness. The patient was given active fluid resuscitation, administered norepinephrine injection to maintain the blood pressure, and was subjected to the tracheal intubation combined with ventilator-assisted ventilation.

The patient condition did not improve significantly, and his family decided to discontinue the further treatment.

L. monocytogenes exist as short, facultative anaerobic, non-spore forming, catalyst-positive, oxidase-negative gram-positive bacilli, and are often found to be arranged in pairs[4,9]. The Listeria genus, includes several species including Listeria gastronomy, Listeria innocuous, Listeria escherichia, L. monocytogenes, Listeria weisei, and Listeria moere. Among them, only L. monocytogenes has been reported to be significantly pathogenic to the humans[4,10]. Listeria is an important food-borne disease[4,11], which can result invasive ailment in the humans and animals, especially causing serious central nervous system infections[9,12]. It primarily causes gastroenteritis in healthy people, while it can also lead to a serious and life-threatening infections in newborns, the elderly, pregnant women, and especially those suffering with cellular immune deficiency[11,13]. For instance, Mylonakis et al[14] investigated 41 different cases of Listeria meningitis (except in newborns or during pregnancy). They reported that the various predisposing factors were as following: 24% of malignant tumors, 21% of transplantation, 13% of alcoholism and liver function insufficiency, 11% of immunosuppressive therapy/steroid use, 8% of diabetes, 7% of HIV and AIDS, and for remaining 36% the exact risk factors could not be determined[15]. We have summarized the details of various patients with intracranial infection caused by Listeria infection in the past 3 years, and found that most of them were immunodeficient patients, and several of them had a history of intake of oral hormones or immunosuppressants (Table 1).

| Ref. | Patient, age, sex (M/F), basic illness | Specific antibiotic treatment for Listeria | Complications | Outcome |

| Zhang et al[21], 2021, China | 64 yr, F, nephrotic syndrome, membranous nephropathy | Ampicillin combined with meropenem | None | Recovered |

| Zhang et al[22], 2021, China | 53 yr, F, SLE | Ampicillin and TMP-SMX, meropenem | None | Discharged |

| Tecellioglu et al[23], 2019, Turkey | 44 yr, F, MS | Imipenem and linezolidShunt surgery | Hastetraparesis | Discharged |

| Cipriani et al[24], 2022, Germany | 69 yr, homeless, type 2 diabetes | A guided stereotactic aspiration and antibiotic therapy with ampicillin and gentamicin | Alight gait disorder | Discharged |

| Zhao et al[25], 2021, China | 68 yr, M | Meropenem and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | None | Recovered |

| Cao et al[26], 2021, China | 50 yr, M | Ampicillin, amikacin, and meropenem | Intermittent mechanical ventilation | Discharged |

| Zhang et al[27], 2021, China | 64 yr, M, tuberculosis and TIA | Piperacillin | None | Discharged |

| Lan et al[28], 2020, China | 66 yr, F | Ampicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | None | Discharged |

| Li et al[29], 2019, China | 37 yr, M | Vancomycin, meropenem, emergent surgery to insert a ventricular drainage tube | Progressed rapidly | Died |

| Ullah et al[18], 2021, United States | 64 yr, M | Not described | Rapidly deteriorated | Died |

| Pereira et al[30], 2020, Brasil | 29 yr, F, SLE | Ceftriaxone, vancomycin and acyclovir | Persisted in a comatose state and developed multiple organ failure, nosocomial bloodstream infection | Died |

| Asaeda et al[31], 2021, Japan | 53 yr, M, moderate ulcerative colitis | Intravenous meropenem and ampicillin | None | Discharged |

| Nakamura et al[32], 2020, Japan | 64 yr, F, relapsed and refractory FL | Meropenem | None | Discharged |

| Morimoto et al[33], 2021, Japan | 41 yr, F, SLE, pregnancy | Ampicillin | None | Recovered |

| Mahesh et al[34], 2020, India | 64 yr, M, ulcerative colitis | Intravenous ampicillin, ceftriaxone | None | Recovered |

| Schutte et al[35], 2019, South Africa | 60 yr, M | Ampicillin and gentamicin for 3 wk | Psychotic episodes | Discharged |

| Schutte et al[35], 2019, South Africa | 55 yr, M, HIV | Ampicillin and gentamicin for 3 wk | None | Discharged |

Invasive L. monocytogenes infection usually manifests itself as bacteremia, accompanied with or without obvious foci of infection, as well as a central nervous system infection, including meningitis, meningoencephalitis, brainstem encephalitis (rhomboid encephalitis), and brain abscess[3,4,8,9]. It has been reported in the literature that monocytogenes is the third most common cause of bacterial meningitis in the elderly, after Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis[14,16]. L. monocytogenes can potentially invade the central nervous system through at least three distinct mechanisms, including: (1) transport through the blood-brain or blood-vessel barrier in the parasitic white blood cells; (2) extracellular blood-derived bacteria can directly invade endothelial cells; or (3) retrograde (centripetal) migration through the brain axons into the brain[4,9]. Monocytic encephalitis is a typical biphasic disease that initially starts with prodromal symptoms lasting 4 d to 5 d, and then can suddenly display various neurological symptoms, including asymmetric cranial nerve palsy, and cerebellum and long fascicular signs[3,8,17]. The typical manifestations of patients include fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, meningeal irritation, ataxia, etc[3,8,17]. Encephalitis is rare and can serve as a focal infection of the cerebral cortex, or it can potentially progress to a brain abscess. The patient showed changes in the consciousness or cognitive dysfunction. The CSF of the patient displayed an increase of 75% of multinucleated cells, consisting mainly of the neutrophils, but monocytes can also be seen[8,9,18]. In addition, about 40% of patients suffering from intracranial infection can display respiratory failure. At this time, the fatality rate is often high, and serious sequelae have been observed. Brain abscesses account for 10% of the central infections. Spinal cord infections are rarely observed in patients[8,9].

During the diagnosis of Listeria monocytic meningoencephalitis (LMM), the positive rate of the blood and cerebrospinal fluid culture is often low due to the intervention of antibiotics[12,17]. In addition, the symptoms and signs of patients with monocytogenes meningitis have been found to be similar to those of the general population of community-acquired bacterial meningitis; however, the prodromal period is relatively longer, the pre-disease symptoms are not typical, and it is often easy to miss the exact diagnosis in the early stage. According to previously reported studies, LMM is sensitive to most antibiotics, including penicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, vancomycin, meropenem, linezolid, levofloxacin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and rifampicin. It is only resistant to fosfomycin and daptomycin, so the selection of the correct antibiotics does not seem to be a difficult choice[4,8,12,19]. However, in actual clinical practice, antibiotic treatment is not often observed to be effective, especially when combined with central nervous system infections, which can lead to an increase in the mortality rate to approximately 25%-30%[4,20]. This might be related to Listeria's ability to effectively invade the host cells and proliferate (such as macrophages, hepatocytes, and neurons) to facilitate an escape from the cytotoxic actions of antibiotics. The prodromal period of Listeria meningitis is often longer, and the exacerbation of the meningitis symptoms can occur after the initial improvement of the patient’s systemic symptoms, thereby leading to a significant delay in the diagnosis of meningitis, which may also be the reason for the higher mortality of patients with meningitis[19]. Therefore, an early identification of Listeria infections, especially the central infections, maybe more important than the choice of antibiotics used for the therapy. Moreover, after the analysis of the various cases of intracranial infection caused by L. monocytogenes in the past 3 years, we have found that most of the patients had neuropsychiatric symptoms of varying degrees at the time of onset of the disease, and most of them were seriously ill and even required respiratory support in the intensive care unit or during operation. With timely, combination and long-term treatment of the various sensitive antibiotics, some patients could recover and were discharged, but the condition of a certain proportion of patients eventually deteriorated and they ultimately died or were left neuropsychiatric sequelae (Table 1)[18,21-35].

In summary, combined with the analysis of this treatment failure case, we have summarized the following experiences and lessons: (1) Early symptoms of Listeria meningitis might be concealed or mild, but proper attention should be paid to careful identification and cerebrospinal fluid examination as soon as possible; (2) meningitis symptoms can suddenly aggravate even after the clinical symptoms show improvement following the treatment; (3) upon retrospective analysis of the patient's first chest CT (Figure 2A and B), scattered nodules were seen in the pleura and under the pleura. At that time, it was necessary to consider the possibility of the blood-borne disseminated lesions. Moreover, in the second reexamination of chest CT (Figure 2C-E), it was found that the number of nodules had increased significantly and developed into patchy shadows, which increased the possibility of blood infection. At that time, multiple blood cultures could have been very important for exact diagnosis; (4) it may be necessary for patients with positive blood cultures to undergo cerebrospinal fluid examination simultaneously; (5) as the background bacterial interference of the cerebrospinal fluid is rather low, metagenomics next-generation sequencing (mNGS) can be used as a highly sensitive and effective method. Therefore, it can be very useful to accurately detect the etiology of cerebrospinal fluid by mNGS; and (6) early identification, adequate, and the relatively long course of treatment might be the key to significantly improve the cure rate of patients with Listeria infection.

For elderly patients, and especially those with immunocompromised conditions who have sepsis or meningoencephalitis, it is necessary to be highly vigilant against the possibility of acquiring a Listeria infection. During the disease, the patient’s history related to consuming an unclean diet should be verified to confirm the exact diagnosis as soon as possible. Adequate treatment with the various sensitive antibiotics is a key factor affecting the prognosis of the disease. In addition, mNGS can potentially serve as a timely and effective detection method to facilitate an early management of the disease.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Microbiology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Keikha M, Iran; Rodrigues AT, Brazil S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Farber JM, Peterkin PI. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 746] [Cited by in RCA: 915] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McCarthy KN, Leahy TR, Murray DM. Listeria Meningitis in an Immunocompetent Child: Case Report and Literature Review. Ir Med J. 2019;112:939. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Schlech WF. Epidemiology and Clinical Manifestations of Listeria monocytogenes Infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Luque-Sastre L, Arroyo C, Fox EM, McMahon BJ, Bai L, Li F, Fanning S. Antimicrobial Resistance in Listeria Species. Microbiol Spectr. 2018;6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rodríguez-Auad JP. [Overview of Listeria monocytogenes infection]. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2018;35:649-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Inoue T, Itani T, Inomata N, Hara K, Takimoto I, Iseki S, Hamada K, Adachi K, Okuyama S, Shimada Y, Hayashi M, Mimura J. Listeria Monocytogenes Septicemia and Meningitis Caused by Listeria Enteritis Complicating Ulcerative Colitis. Intern Med. 2017;56:2655-2659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee JE, Cho WK, Nam CH, Jung MH, Kang JH, Suh BK. A case of meningoencephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes in a healthy child. Korean J Pediatr. 2010;53:653-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pagliano P, Arslan F, Ascione T. Epidemiology and treatment of the commonest form of listeriosis: meningitis and bacteraemia. Infez Med. 2017;25:210-216. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Drevets DA, Bronze MS. Listeria monocytogenes: epidemiology, human disease, and mechanisms of brain invasion. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;53:151-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Troxler R, von Graevenitz A, Funke G, Wiedemann B, Stock I. Natural antibiotic susceptibility of Listeria species: L. grayi, L. innocua, L. ivanovii, L. monocytogenes, L. seeligeri and L. welshimeri strains. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000;6:525-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pizarro-Cerdá J, Cossart P. Microbe Profile: Listeria monocytogenes: a paradigm among intracellular bacterial pathogens. Microbiology (Reading). 2019;165:719-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | 12 Chen SY, Lee JJ, Chien CC, Tsai WC, Lu CH, Chang WN, Lien CY. High incidence of severe neurological manifestations and high mortality rate for adult Listeria monocytogenes meningitis in Taiwan. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;71:177-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Castellazzi ML, Marchisio P, Bosis S. Listeria monocytogenes meningitis in immunocompetent and healthy children: a case report and a review of the literature. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44:152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mylonakis E, Hohmann EL, Calderwood SB. Central nervous system infection with Listeria monocytogenes. 33 years' experience at a general hospital and review of 776 episodes from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:313-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Beamonte Vela BN, Garcia-Carretero R, Carrasco-Fernandez B, Gil-Romero Y, Perez-Pomata MT. Listeria monocytogenes infections: Analysis of 41 patients. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;155:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pagliano P, Ascione T, Boccia G, De Caro F, Esposito S. Listeria monocytogenes meningitis in the elderly: epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic findings. Infez Med. 2016;24:105-111. [PubMed] |

| 17. | O'Callaghan M, Mok T, Lefter S, Harrington H. Clues to diagnosing culture negative Listeria rhombencephalitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ullah A, Patterson GT, Mattox SN, Cotter T, Patel NG, Savage NM. Double-Negative T-Cell Reaction in a Case of Listeria Meningitis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yu W, Huang Y, Ying C, Zhou Y, Zhang L, Zhang J, Chen Y, Qiu Y. Analysis of Genetic Diversity and Antibiotic Options for Clinical Listeria monocytogenes Infections in China. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hof H, Nichterlein T, Kretschmar M. Management of listeriosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:345-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang J, Huang S, Xu L, Tao M, Zhao Y, Liang Z. Brain abscess due to listeria monocytogenes: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e26839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang N, Sun W, Zhou L, Chen M, Dong X, Wei W. Multiple brain abscesses due to Listeria monocytogenes infection in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report and literature review. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24:1427-1439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tecellioglu M, Kamisli O, Kamisli S, Erdogmus UA, Özcan C. Listeria monocytogenes rhombencephalitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis during fingolimod therapy. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;27:409-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cipriani D, Trippel M, Buttler KJ, Rohr E, Wagner D, Beck J, Schnell O. Cerebral Abscess Caused by Listeria monocytogenes: Case Report and Literature Review. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2022;83:194-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhao Y, Xu C, Tuo H, Liu Y, Wang J. Rhombencephalitis due to Listeria monocytogenes infection with GQ1b antibody positivity and multiple intracranial hemorrhage: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060521998568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cao L, Lin Y, Jiang H, Wei J. Severe invasive Listeria monocytogenes rhombencephalitis mimicking facial neuritis in a healthy middle-aged man: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060520982653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhang X, Wang R, Luo J, Xia D, Zhou C. Detection of meningoencephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes with ischemic stroke-like onset using metagenomics next-generation sequencing: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e26802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lan ZW, Xiao MJ, Guan YL, Zhan YJ, Tang XQ. Detection of Listeria monocytogenes in a patient with meningoencephalitis using next-generation sequencing: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li N, Huang HQ, Zhang GS, Hua W, Shen HH. Encephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes in a healthy adult male in China: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pereira MEVDC, Gonzalez DE, Roberto FB, Foresto RD, Kirsztajn GM, Durão Júnior MS. Listeria monocytogenes meningoencephalitis in a patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Bras Nefrol. 2020;42:375-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Asaeda K, Okuyama Y, Nakatsugawa Y, Doi T, Yamada S, Nishimura K, Fujii H, Tomatsuri N, Satoh H, Kimura H. [A case of Listeria meningitis with active ulcerative colitis and a review of literature in the Japanese cases]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2021;118:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nakamura F, Nasu R. Listeria monocytogenes septicemia and meningoencephalitis associated with relapsed and refractory follicular lymphoma. J Infect Chemother. 2020;26:619-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Morimoto M, Fujikawa K, Ide S, Akagi M, Fujiwara E, Mizokami A, Kawakami A. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Complicated with Listeria Monocytogenes Infection in a Pregnant Woman. Intern Med. 2021;60:1627-1630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mahesh KV, Shree R, Shah J, Modi M. Listeria rhombencephalitis with hydrocephalus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91:562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Schutte CM, Van der Meyden CH, Kakaza M, Lockhat Z, Van der Walt E. Life-threatening Listeria meningitis: Need for revision of South African acute bacterial meningitis treatment guidelines. S Afr Med J. 2019;109:296-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |