Published online Oct 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i29.10535

Peer-review started: July 20, 2021

First decision: October 16, 2021

Revised: November 27, 2021

Accepted: September 1, 2022

Article in press: September 1, 2022

Published online: October 16, 2022

Processing time: 435 Days and 19 Hours

Malignant splenic tumors are rare but fatal, presenting a challenge in diagnosis and management involving hematology, oncology, and general surgery. By contrast, diagnosing and treating other common malignant tumors (such as lung and gastrointestinal cancer) offers multiple strategies for chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy with the prospect of a cure. With various specialists involved in clinical multiple disciplinary team (MDT) discussion, personal bias can be minimized. It can also ignite important discussion which can benefit not only one patient but many patients.

Here, we report on the MDT diagnosis and management of the malignant splenic tumors littoral cell angiosarcoma and histiocytic sarcoma. Although only two cases of rare primary splenic malignancy are presented, MDT is a novel means of rare disease treatment.

To benefit patients, imaging analysis, safe operation, precise pathology exami

Core Tip: Malignant splenic tumors are rare but fatal, presenting a challenge in diagnosis and management. With various specialists involved in clinical multiple disciplinary team discussion, personal bias can be minimized. It can also ignite important discussion which can benefit not only one patient but many patients. In this article, we report the multiple disciplinary team (MDT) diagnosis and management of the malignant splenic tumors littoral cell angiosarcoma and histiocytic sarcoma. Although only two cases of rare primary splenic malignancy are presented, MDT is a novel means of rare disease treatment.

- Citation: Luo H, Wang T, Xiao L, Wang C, Yi H. Multiple disciplinary team management of rare primary splenic malignancy: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(29): 10535-10542

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i29/10535.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i29.10535

Splenic masses include benign and malignant tumors. Although the most common benign splenic tumor is angioma, the spleen is not a preferred organ for primary malignant tumors[1]. Due to the absence of typical clinical characteristics or imaging methods, it is extremely difficult to distinguish between malignant and benign splenic tumors before surgery[2]. Diagnosing and managing splenic tumors involves hematology, oncology, and general surgery, making multiple disciplinary team (MDT) management necessary. In this case series, we report the use of a MDT to diagnose and manage rare malignant splenic tumors. Due to the various specialists involved in clinical MDT discussion, personal bias can be minimized. It can also ignite important discussion which can benefit not only one patient but many patients.

Case 1: A 77-year-old female presented to the emergency room with sudden onset of dizziness that had lasted 10 h and prone to falling for 8 h.

Case 2: A 60-year-old female was referred to our hospital following the incidental detection of a splenic mass by ultrasonic scan with thrombocytopenia.

Case 1: The 77-year-old female presented to the emergency room with sudden onset of dizziness that had lasted 10 h and prone to falling for 8 h.

Case 2: This patient presented no other symptoms such as fever, weight loss, dizziness, or night sweats.

Case 1: The patient had no previous illnesses.

Case 2: Her most recent imaging scan and laboratory examination was traced back to 2009. Upon hospital admission for an elbow fracture, an abdominal ultrasonic scan showed no positive results for the spleen and testing indicated a slightly reduced platelet count of 115 × 109/L.

Case 1: No similar disorders were noted in her family members.

Case 2: No similar disorders were noted in her family members.

Case 1: Her heart rate was 120 bpm, blood pressure was 106/60 mmHg and respiratory rate was 26 breaths/min. Upon physical examination, the left costal margin exhibited tenderness without muscle intensive or rebound tenderness.

Case 2: Upon physical examination, the spleen was found to be slightly enlarged and palpable 2 cm below the left costal margin. There was no purpura on the body but some vascular nevi approximately 1 mm in size were noted.

Case 1: A complete blood count indicated anemia and thrombocytopenia. Her peripheral hemoglobin was 85 g/L (normal range, 115-150 g/L) with a red blood cell count of 2.65 × 1012/L (normal range, 3.80-5.10 × 1012/L) and a platelet count of 35 × 109/L (normal range, 125-350 × 109/L). Coagulation examination indicated hypocoagulability with a prolonged prothrombin time (PT; 15.10 s, normal range, 9.00-13.00 s) and internal normalized ratio (INR; 1.32, normal range, 0.8-1.20), with a D-dimer level more than 70 mg/L (normal range, 0-0.55 mg/L).

Case 2: A complete blood count showed slight anemia (111 g/L) and thrombocytopenia (34 × 109/L) with a normal leukocyte count (4.83 × 109/L). Coagulation, hepatic marker, and tumor marker tests were negative. Bone marrow aspiration showed a subnormal proliferation of bone marrow without atypical cells and myelofibrosis.

Case 1: Emergency ultrasonic examination indicated the spleen was oversized, with non-uniform echoes accompanied by abdominal fluid collection. A subsequent diagnostic puncture contained uncoagulated blood, proving abdominal bleeding. The patient was diagnosed with blunt abdominal trauma and a splenic rupture.

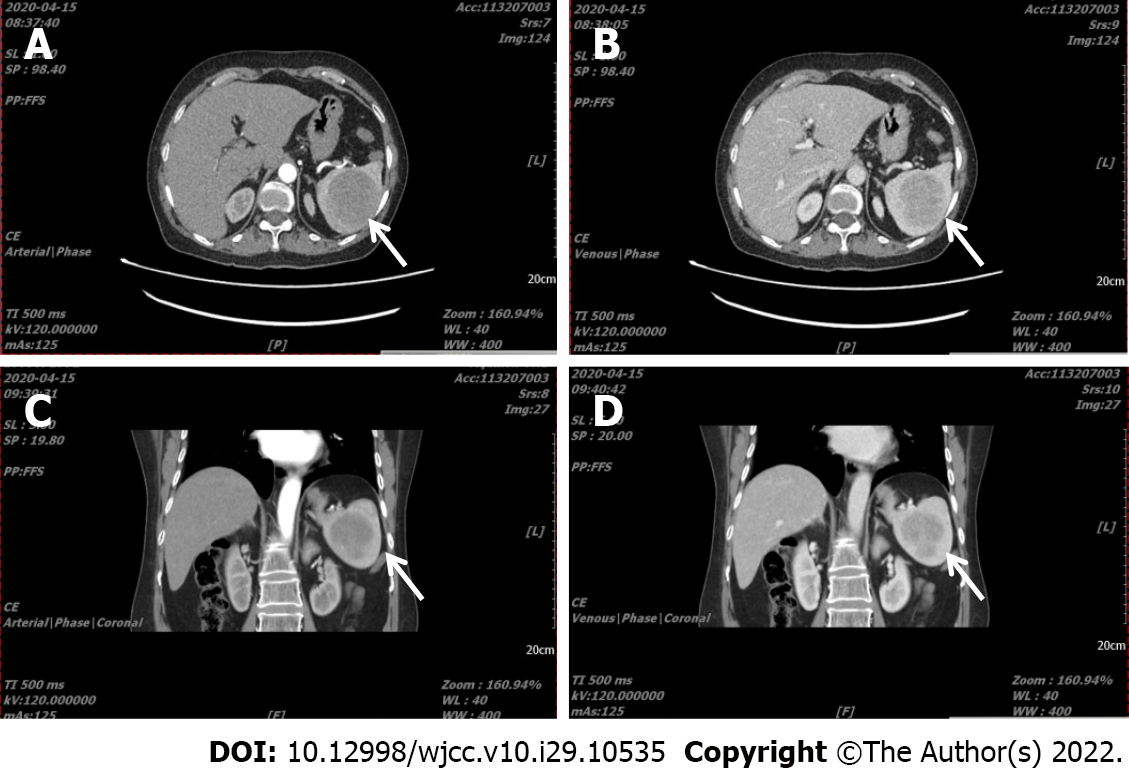

Case 2: An abdominal Computed Tomography (CT) angiograph scan revealed splenomegaly and a tumor (6.0 cm × 5.7 cm in size), with a CT value of 48 HU and showing gradual enhancement (Figure 1, the arrow indicates the mass in the spleen). A general lymph node ultrasonic scan identified no enlarged superficial or abdominal lymph nodes. The patient refused PET/CT examination.

A post-operation MDT conference was arranged before her discharge. The oncologist remarked on controversial biological features of littoral cell angioma (LCA)[3]. Initially, the LCA was considered a benign splenic tumor, but subsequent evidence confirmed malignancy via distinguishing intermediate features[4]. Given its low grade, the oncologist advised there was no need for further treatment.

A preoperative MDT conference was convened, including an imaging physician, general surgeon, hematologist, and oncologist. Radiologically, the CT value of the mass was similar to that of the normal spleen, but the enhanced mode represented a quick infusion and slow dispersion. This was consistent with the imaging features of splenic angioma. Surgically speaking, Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (KMS) was highly suspected because of the imaging characteristics combined with thrombocytopenia and the vascular nevi on her back. To diagnose, cure KMS, and ameliorate thrombocytopenia, splenectomy can be a better choice[5,6]. However, the other surgeon reminded us of Case 1 [whose postoperative pathologic diagnosis indicated littoral cell angiosarcoma (LCAS)] so splenic malignancy could not be fully eliminated despite there being no splenic mass according to the patient’s 2009 history. The hematologist stated that negative bone marrow aspiration and lymph node ultrasonic scan results could partially rule out lymphoma. Following the MDT discussion, possible diagnoses were splenic KMS, splenic malignancy, lymphoma, or other hematologic disease.

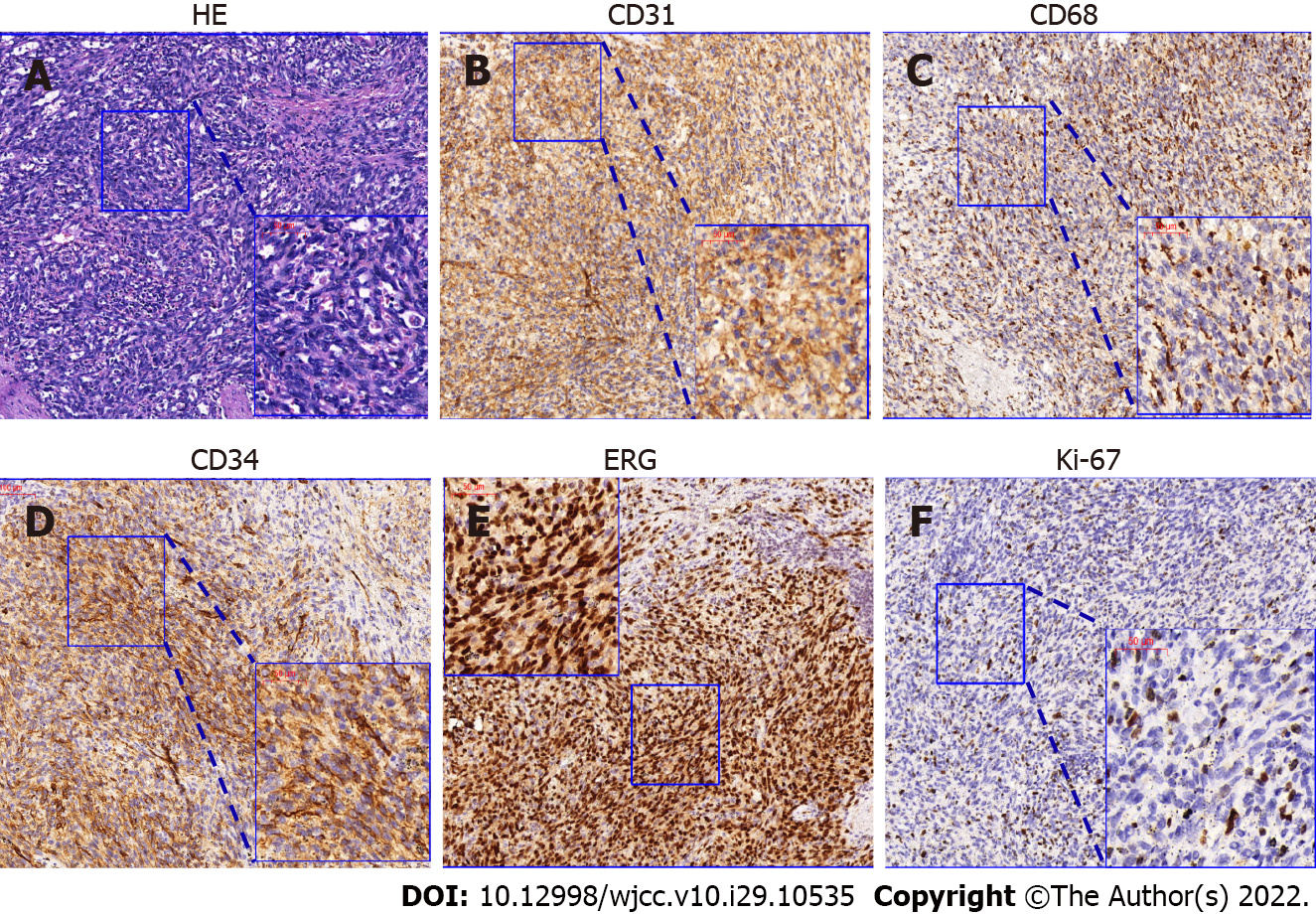

The patient accepted an emergency splenectomy. The immunohistochemical results demonstrated that the tumor cells were CD34+/ERG+/CD31+/CD8+/CD68+/Lysozyme+/F8+, sox-10-/S-100-, P53local+, and Ki-67(+, 5-10%) (Table 1). Based on the positivity of both endothelial (CD34, ERG, and Cd31) and histiocytic markers (CD68, CD8, Lysozyme, and F8), she was ultimately diagnosed with a ruptured LCAS (Figure 2).

| Immunohistochemical markers | AS | HS | Case 1 | Case 2 |

| CD4 | Positive | ∕ | Positive | |

| Lysozyme | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| CD45 | Positive | ∕ | Positive | |

| CD31 | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| ERG | Positive | Positive | Negative | |

| CD34 | Positive | Positive | Negative | |

| CD68 | Positive | Positive | Focally positive | Positive |

| CD163 | Positive | ∕ | Negative | |

| CD8 | Positive | Negative | ||

| S-100 | Positive | Negative | Negative | |

| CD21 | ∕ | Negative | ||

| CK | Positive | ∕ | Negative | |

| F8 | Positive | Positive | Positive | ∕ |

| SMA | Positive | Positive | ∕ | |

| Sox-10 | Negative | ∕ | ||

| Ki-67 | Positive, 5%-10% | Positive, 15%-20% | ||

| P53 | Positive | Negative |

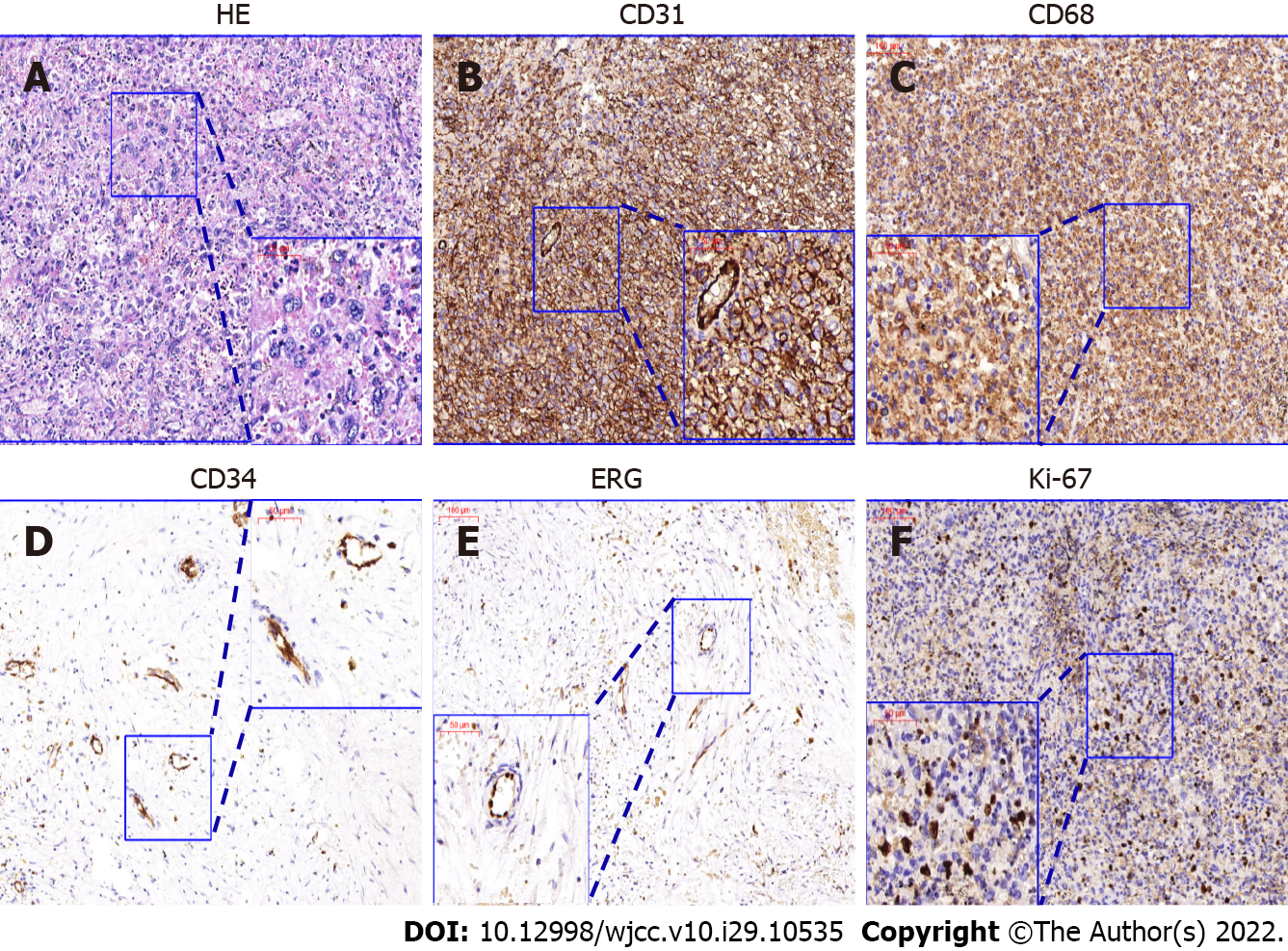

Case 2: Following the pre-operative MDT conference, all physicians and the patient agreed to laparoscopic splenectomy to treat the KMS and ameliorate thrombocytopenia. During surgery, the peritoneal cavity was carefully explored and there were no indications of enlarged lymph nodes or suspicious lesions. The postoperative pathology diagnosis confirmed splenic sarcoma. According to immunohistochemical markers (Table 1), a diagnosis of angiosarcoma or histiocytic sarcoma (HS) confused pathologists. In the postoperative MDT conference, the pathologist revealed that the tumor contained multiple large cells with abundant blue cytoplasm, in which the binucleated and trinucleated cells could also be observed (Figure 3). The CD4+/CD68+/Lysozyme+/CD45+/CD31+ tumor cells coincided with typical HS marker expression[7]. However, there was marker overlap, with Lysozyme, CD31, CD68, and F8 covering HS, angiosarcoma, and other malignancy[7,8]. Hematoxylin-eosin staining showed no typical epithelial or dilated vessels; thus, the pathology results suggested the diagnosis of HS (Figure 3).

Given its low grade, the oncologist advised there was no need for further treatment.

The oncologist indicated that neither HS nor angiosarcoma was sensitive to chemotherapy, which is consistent with few patients obtaining benefit from chemotherapy[9,10]. The hematologist advised that trametinib[11,12] and/or imatinib[13] could be beneficial in this patient. It has been reported that chronic myeloid leukemia, other types of leukemia and HS present similar medical features[10,14]. These features might be therapeutic targets for imatinib. The patient subsequently consented to oral imatinib treatment (400 mg, qd).

The patient was lost to follow-up after surgery.

The latest follow-up showed that the patient has been tumor-free for more than 15 mo.

Primary splenic malignancy is rare but fatal. It does not present typical clinical symptoms, so it is difficult to diagnose pre-operatively. The most common symptoms are hemophagocytosis-related symptoms (e.g., anemia accompanied by dizziness, anergy, loss of appetite) or thrombocytopenia-related symptoms (e.g., purpura or mucosal bleeding)[15]. However, it is difficult to differentiate these symptoms from those of lymphoma or other benign splenic tumors, such as angioma. With regard to treatment, splenic malignancy tumor is so rare that few guidelines and limited data exist. Therefore, to make an accurate decision for these patients, a general surgeon, an oncologist, a hematologist, a pathologist, and an imaging physician are required. A MDT meeting is a regularly scheduled discussion of patients, comprising professionals from different specialties, such as surgeons, medical and radiation oncologists, radiologists, pathologists and nurse specialists[16]. MDT meetings first appeared in 1970’s in America and were known as tumor boards to discuss cases by a group of specialists[17]. MDT meetings were set up to give specialists the opportunity to update new developments in disease diagnosis and provide the patient with the most suitable treatment[18]. MDT management has been widely applied in cancer management and recommended as best practice by professional guidelines[19]. MDT meetings can be held at every stage of patient management, including precise diagnosis, initial management plans, treatment changes, shorter time to treatment after diagnosis, and better survival. For some rare diseases, diagnosis is the most challenging problem. With the help of MDT meetings, in Case 1, the surgeons and emergency physicians believed that spleen rupture was secondary to blunt trauma. During the MDT discussion, the pathologist pointed out that spontaneous splenic rupture of LCA is not uncommon, and can be as high as 32%[20]. Although we made the right choice to perform emergency surgery, an emergency physician or general surgeon might misdiagnose such a patient. The pathologist from the MDT gave us some clues, and a careful review of medical history illustrated another probable process. Spontaneous splenic LCA rupture can result in dizziness followed by prone to falling. In Case 2, a misdiagnosis was identified, with the patient’s initial diagnosis of KMS making surgery appear unavoidable. However, the assessment of Case 1 reminded us of the possibility of a malignant splenic tumor. Although it is difficult to differentiate primary splenic malignancy from lymphoma or other benign tumors, pre-operatively the MDT members unanimously agreed on surgery, helping to determine the most suitable clinical strategy. MDT meetings can benefit patients suffering from rare diseases, when the diagnosis is difficult as in Case 2. In addition, MDT management can reduce the time from diagnosis to treatment. For physicians, a MDT can have several advantages as it can improve communication between MDT members, provide doctors with the opportunity for further education, keep up to date with new developments, and improve job satisfaction[21].

Furthermore, MDT discussion is necessary for treatment. The postoperative MDT conference for Case 2 included a debate regarding whether the diagnosis was angiosarcoma or HS. Historically, HS has been classified together with histiocytic lymphoma, and the 2016 revision of the WHO classification placed HS into the macrophage-dendritic cell lineage along with other histiocytoses as well as myeloid-derived and stromal-derived dendritic cell tumors[22]. The diagnosis relies on immunohistochemistry, specifically positive expression of mature histiocytic markers (such as CD4, CD68, CD163, and lysozyme) and negative expression of Langerhans and dendritic cellular markers (e.g., CD1a, Langerin, CD21, and CD35)[7].

However, HS represents an extremely heterogeneous feature with complicated markers. For example, both HS and angiosarcoma positively express CD68, CD31, and Lysozyme[7,8], which were positive in Case 1. As such, some pathologists diagnosed Case 2 as splenic angiosarcoma. After an in-depth MDT discussion and literature review, the diagnosis of HS was confirmed.

Following therapy is another focus. Few guidelines and limited data are available on HS treatment, and most HSs have limited response to chemotherapy[10,23]. HS is very aggressive with a poor prognosis and has a median survival of several months[11,24-27]. Therefore, experimental treatment of imatinib was recommended. At follow-up, our HS patient treated with imatinib has been tumor-free for more than 15 mo. This targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor may be a future direction for HS management.

Although some physicians have indicated that MDT meetings will not have a beneficial effect on outcomes such as survival rates in patients with common malignant tumors (such as lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, and leukemia), they may be beneficial in those who are suffering diseases which are difficult to accurately diagnose. Diagnosing and treating common malignant tumors poses little challenge due to multiple available technology and treatment strategies (e.g., chemotherapy, radio

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arigami T, Japan; Maglangit SACA, Philippines; Marickar F, India S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Yamamoto S, Tsukamoto T, Kanazawa A, Shimizu S, Morimura K, Toyokawa T, Xiang Z, Sakurai K, Fukuoka T, Yoshida K, Takii M, Inoue K. Laparoscopic splenectomy for histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | PAREIRA MD, PROBSTEIN JG. Surgical aspects of primary splenic neoplasms. Am J Surg. 1951;81:584-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liu D, Chen Z, Wang T, Zhang B, Zhou H, Li Q. Littoral-cell angioma of the spleen: a case report. Cancer Biol Med. 2017;14:194-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rosso R, Paulli M. Littoral cell angiosarcoma: a truly malignant tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tang JY, Chen J, Pan C, Yin MZ, Zhu M. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the spleen with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome misdiagnosed as idiopathic thrombocytopenia in a child. World J Pediatr. 2008;4:227-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dufau JP, le Tourneau A, Audouin J, Delmer A, Diebold J. Isolated diffuse hemangiomatosis of the spleen with Kasabach-Merritt-like syndrome. Histopathology. 1999;35:337-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hung YP, Qian X. Histiocytic Sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144:650-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kranzfelder M, Bauer M, Richter T, Rudelius M, Huth M, Wagner P, Friess H, Stadler J. Littoral cell angioma and angiosarcoma of the spleen: report of two cases in siblings and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:863-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Copie-Bergman C, Wotherspoon AC, Norton AJ, Diss TC, Isaacson PG. True histiocytic lymphoma: a morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1386-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ansari J, Naqash AR, Munker R, El-Osta H, Master S, Cotelingam JD, Griffiths E, Greer AH, Yin H, Peddi P, Shackelford RE. Histiocytic sarcoma as a secondary malignancy: pathobiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur J Haematol. 2016;97:9-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gounder MM, Solit DB, Tap WD. Trametinib in Histiocytic Sarcoma with an Activating MAP2K1 (MEK1) Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1945-1947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Takada M, Hix JML, Corner S, Schall PZ, Kiupel M, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V. Targeting MEK in a Translational Model of Histiocytic Sarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:2439-2450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Voruz S, Cairoli A, Naveiras O, de Leval L, Missiaglia E, Homicsko K, Michielin O, Blum S. Response to MEK inhibition with trametinib and tyrosine kinase inhibition with imatinib in multifocal histiocytic sarcoma. Haematologica. 2018;103:e39-e41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rassidakis GZ, Stromberg O, Xagoraris I, Jatta K, Sonnevi K. Trametinib and Dabrafenib in histiocytic sarcoma transdifferentiated from chronic lymphocytic leukemia with a K-RAS and a unique BRAF mutation. Ann Hematol. 2020;99:649-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yamada S, Tasaki T, Satoh N, Nabeshima A, Kitada S, Noguchi H, Yamada K, Takeshita M, Sasaguri Y. Primary splenic histiocytic sarcoma complicated with prolonged idiopathic thrombocytopenia and secondary bone marrow involvement: a unique surgical case presenting with splenomegaly but non-nodular lesions. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kurpad R, Kim W, Rathmell WK, Godley P, Whang Y, Fielding J, Smith L, Pettiford A, Schultz H, Nielsen M, Wallen EM, Pruthi RS. A multidisciplinary approach to the management of urologic malignancies: does it influence diagnostic and treatment decisions? Urol Oncol. 2011;29:378-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gross GE. The role of the tumor board in a community hospital. CA Cancer J Clin. 1987;37:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Patkar V, Acosta D, Davidson T, Jones A, Fox J, Keshtgar M. Cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: evidence, challenges, and the role of clinical decision support technology. Int J Breast Cancer. 2011;2011:831605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, Novello S, Smit EF, Faivre-Finn C, Mok TS, Reck M, Van Schil PE, Hellmann MD, Peters S; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv192-iv237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1392] [Cited by in RCA: 1587] [Article Influence: 226.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Neuhauser TS, Derringer GA, Thompson LD, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, Saaristo A, Abbondanzo SL. Splenic angiosarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 28 cases. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:978-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Taylor C, Sippitt JM, Collins G, McManus C, Richardson A, Dawson J, Richards M, Ramirez AJ. A pre-post test evaluation of the impact of the PELICAN MDT-TME Development Programme on the working lives of colorectal cancer team members. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4245] [Cited by in RCA: 5366] [Article Influence: 596.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Oka K, Nakamine H, Maeda K, Yamakawa M, Imai H, Tada K, Ito M, Watanabe Y, Suzuki H, Iwasa M, Tanaka I. Primary histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen associated with hemophagocytosis. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:405-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vos JA, Abbondanzo SL, Barekman CL, Andriko JW, Miettinen M, Aguilera NS. Histiocytic sarcoma: a study of five cases including the histiocyte marker CD163. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:693-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hornick JL, Jaffe ES, Fletcher CD. Extranodal histiocytic sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 14 cases of a rare epithelioid malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1133-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hung YP, Lovitch SB, Qian X. Histiocytic sarcoma: New insights into FNA cytomorphology and molecular characteristics. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125:604-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kommalapati A, Tella SH, Durkin M, Go RS, Goyal G. Histiocytic sarcoma: a population-based analysis of incidence, demographic disparities, and long-term outcomes. Blood. 2018;131:265-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |