Published online Oct 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10252

Peer-review started: April 29, 2022

First decision: May 11, 2022

Revised: May 31, 2022

Accepted: August 5, 2022

Article in press: August 5, 2022

Published online: October 6, 2022

Processing time: 150 Days and 17 Hours

Amyloidosis is a rare disease characterized by extracellular deposition of misfolded protein aggregated into insoluble fibrils. Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic amyloidosis is common, but is often subclinical or presents as vague and nonspecific symptoms. It is rare for gastrointestinal symptoms to be the main presenting symptom in patients with systemic amyloidosis, causing it to be undiagnosed until late-stage disease.

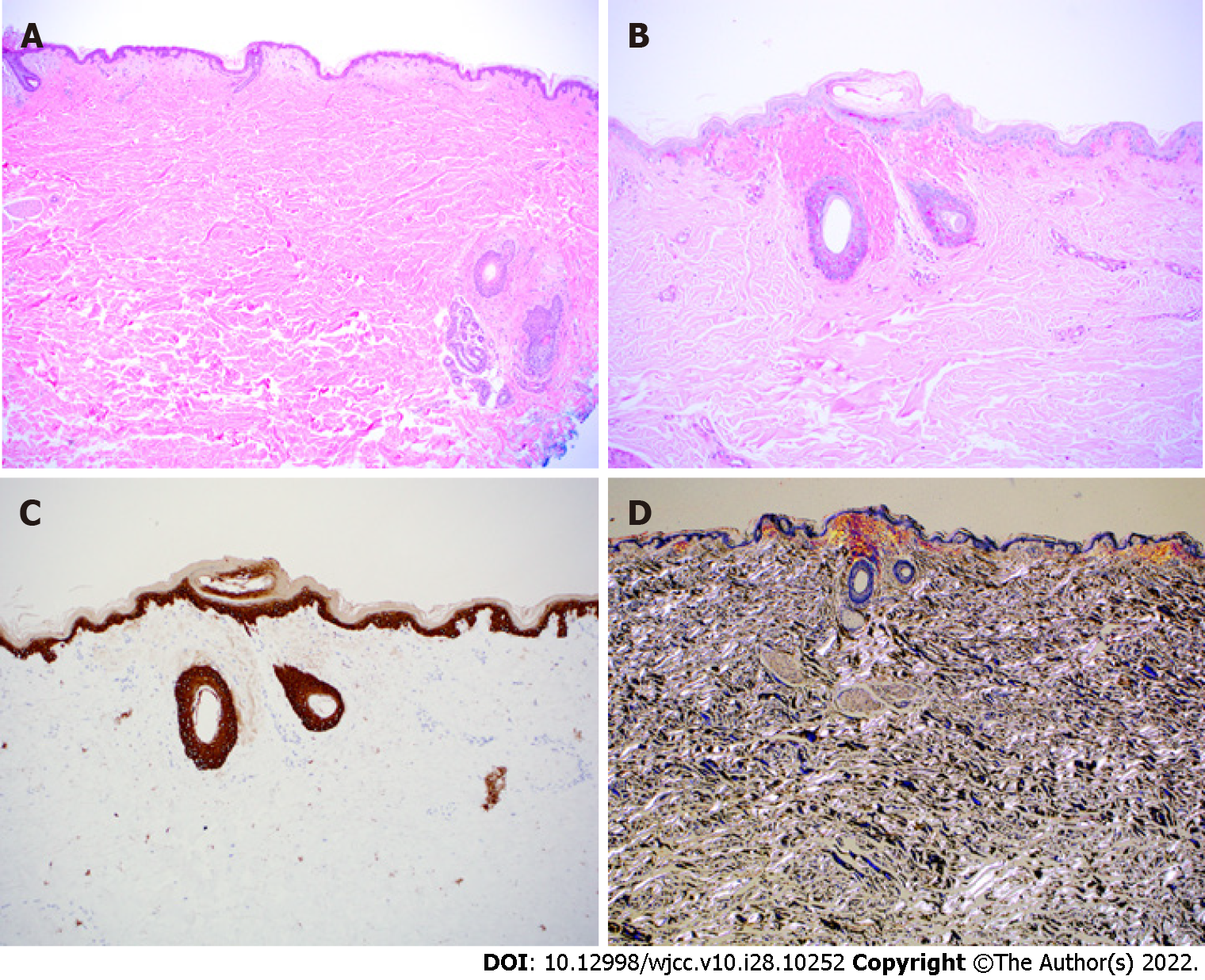

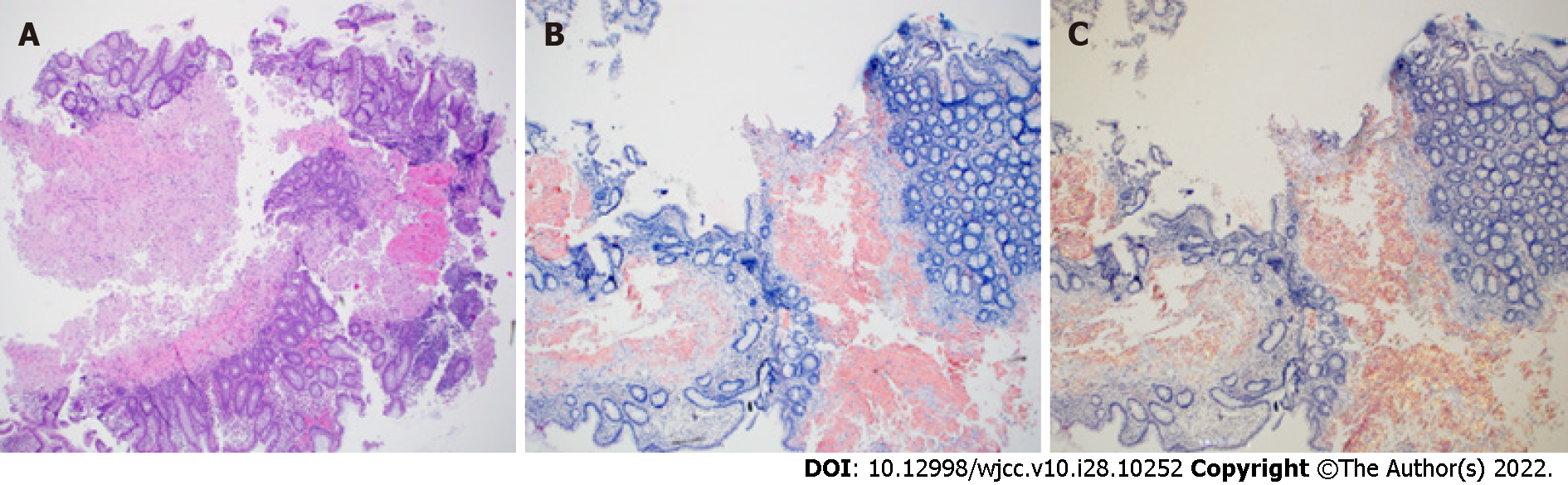

A 53 year-old man with diarrhea, hematochezia, and weight loss presented to a community hospital. Colonoscopy with biopsy at that time was suspicious for Crohn disease. Due to worsening symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and a new petechial rash, an abdominal fat pad biopsy was done. The biopsy showed papillary and adnexal dermal amyloid deposition, in a pattern usually seen with cutaneous amyloidosis. However, Cytokeratin 5/6 was negative, excluding cutaneous amyloidosis. The patterns of nodular amyloidosis, subcutaneous amyloid deposits and perivascular amyloid were not seen. Periodic Acid-Schiff stain was negative for lipoid proteinosis, Congo red was positive for apple green birefringence on polarization and amyloid typing confirmed amyloid light chain amyloidosis. Repeat endoscopic biopsies of the gastrointestinal tract showed amyloid deposition from the esophagus to the rectum, in a pattern usually seen in serum amyloid A in the setting of chronic inflammatory diseases, including severe inflammatory bowel disease. Bone marrow biopsy showed kappa-restricted plasma cell neoplasm.

Described is an unusual presentation of primary systemic amyloidosis, highlighting the risk of misdiagnosis with subsequent significant organ dysfunction and high mortality.

Core Tip: Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic amyloid light (AL) amyloidosis is rare, and symptoms are usually subclinical. Diarrhea and hematochezia have rarely been the primary presenting symptom of AL amyloidosis. It is critically important to diagnose and treat amyloidosis early to prevent severe morbidity and mortality.

- Citation: Bilton SE, Shah N, Dougherty D, Simpson S, Holliday A, Sahebjam F, Grider DJ. Persistent diarrhea with petechial rash - unusual pattern of light chain amyloidosis deposition on skin and gastrointestinal biopsies: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(28): 10252-10259

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i28/10252.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i28.10252

Amyloidosis is a rare disease characterized by extracellular deposition of misfolded protein aggregated into insoluble fibrils[1]. Arranged in an anti-parallel, cross-β-pleated sheet configuration, these fibrils are resistant to proteolytic cleavage and have specific tropism for tissue sites such as the heart, liver, kidney, and peripheral nervous system[2]. Amyloidosis is classified by the fibril precursor protein[3]. Six types of amyloidosis are generally recognized: primary (associated with monoclonal light chains in serum and/or urine), secondary (associated with inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic diseases), hemo

Early clinical features of AL amyloidosis are often vague and nonspecific, such as weight loss and fatigue, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment[6]. Approximately 30% of patients with AL amyloidosis are diagnosed with advanced, late stage disease presenting with symptoms of end-stage organ damage with survival of only 3-6 mo[7]. The degree of cardiac involvement is the critical prognostic factor for patients with AL amyloidosis[8]. Cardiac involvement is common in amyloidosis, affecting 75%-80% of patients at diagnosis and is evident by elevated N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and visualization on echocardiography[8,9]. Renal involvement is found in 60%-75% of patients with AL amyloidosis, manifested as nephrotic range proteinuria and progressing to end stage renal disease[8]. Gastrointestinal involvement in amyloidosis with biopsy-proven disease is rare, as evident by a single center, 13-year retrospective study where 3.2% of patients with amyloidosis had biopsy-confirmed gastrointestinal amyloid involvement[10]. However, gastrointestinal amyloid involvement and symptoms are relatively common but often are subclinical and not typically the presenting symptom[3]. Reported symptoms of gastrointestinal amyloidosis include nausea, constipation, abdominal pain, reflux, weight loss, and gastrointestinal bleeding[10]. When amyloid deposition diffusely involves the tubular gastrointestinal tract, serum amyloid A should be considered, especially in the setting of chronic inflammatory conditions or autoimmune diseases[11]. By comparison, biopsies in the setting of AL amyloidosis can have nodular amyloid deposition rather than diffuse deposition involving the entire tubular gastrointestinal tract.

If amyloidosis is suspected, biopsy with histological confirmation is standard, usually an abdominal fat pad or rectal biopsy. Congo red staining of amyloid containing tissues results in the characteristic apple-green birefringence when viewed under polarized light[12]. Confirmation of amyloid type is done by mass spectrometry.

A 53-year-old man with a largely unremarkable past medical history was hospitalized with worsening diarrhea, hematochezia, weight loss, abdominal pain, and petechial rash of the trunk, arms, neck, and face including eyelids (Figure 1). The patient reported 6 mo of chronic diarrhea with intermittent hematochezia and an associated 13.5-18 kg weight loss.

Two weeks prior to his presentation at our institution, the patient presented to an outside community hospital’s emergency department with the above symptoms. At this community hospital, the patient underwent colonoscopy to the proximal colon with three biopsies by a general surgeon. Colonoscopy showed edematous, friable mucosa from the rectum to cecum. The pathology report noted acute and chronic inflammation with preserved glandular architecture, suspicious for Crohn disease. The patient was discharged from this outside hospital in stable condition and scheduled follow-up for presumed Crohn disease. Due to worsening symptoms of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dyspnea, and rash, he presented to the emergency department at our institution.

On initial examination, he was ill-appearing with a diffusely tender abdomen and a new petechial rash over the face and areas of pressure on his neck, arms, and abdomen. His lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally without wheezing. His heart was in regular rhythm with increased rate and without murmur. In the emergency department, his vitals showed he was hypotensive, tachycardic, afebrile, and non-hypoxic on room air. His blood pressure dropped to 87/50 mmHg requiring intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation, but did not require vasopressors.

Initial labs revealed anemia (Hgb 9.1 g/dL, Hct 27.9%, RDW 15.4%, MCV 80.9 fL) and platelet count within normal limits at 233 k/μL. Chemistry panel showed acute kidney injury with Cr 1.57 mg/dL as well as low calcium of Ca 7.7mg/dL, elevated BUN of 21 mg/dL, and low albumin of 1.9 g/dL. C-reactive protein within normal limits at 0.80 mg/dL. Labs showed high stool lactoferrin of 332.15 μg/mL (normal range 0-7.24 μg/mL) and high pro-BNP of 10212 pg/mL (normal range < 125 pg/mL). Folate and thiamine labs were low. Urinalysis was remarkable for proteinuria of 100 mg/dL and the presence of numerous hyaline casts and coarse granular casts.

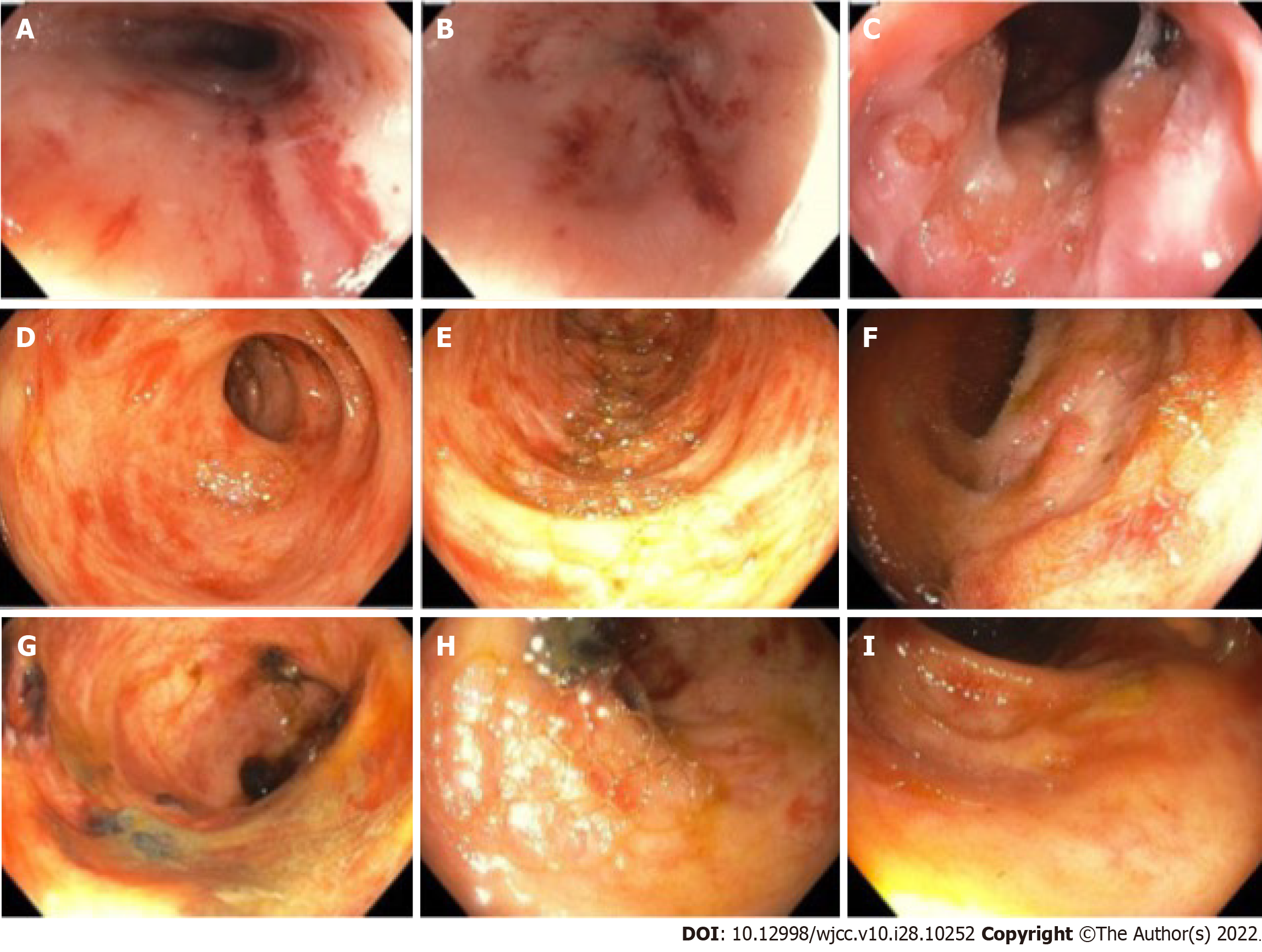

Imaging studies were performed including computer tomography (CT) chest, abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast. CT chest showed a moderate pericardial effusion and trace pleural effusions. CT abdomen/pelvis showed moderate wall thickening of the small bowel loops and colon extending from the cecum to the transverse colon (Figure 2), concerning for enterocolitis of infectious vs inflammatory etiology. No bone fractures or suspicious osseous abnormalities seen on any imaging. Echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular ejection fraction and small to moderate sized circumferential pericardial effusion without evidence of tamponade.

The initial multidisciplinary work up was based on the suspected diagnosis of Crohn disease. Upon dermatology evaluation of a petechial skin rash, a fat pad biopsy was performed (Figure 3) to rule out possible amyloidosis or the unlikely possibility of metastatic cutaneous Crohn disease. Gastroenterology performed esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy with biopsies from the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, terminal ileum, and colon (Figures 4 and 5). Both the fat pad biopsy and all biopsies from the gastrointestinal tract showed pink amorphous material. Interestingly, the pink amorphous material in the abdominal fat pad biopsy was only found just below the epidermis in the papillary dermis and in the upper periadenexal dermis of pilosebaceous units (Figure 3). This pattern of amyloid deposition is typically seen in primary cutaneous amyloidosis of macular or lichen subtype, or rarely in lipoid proteinosis[13,14]. Cytokeratin 5/6 was only blush positive and thus interpreted as negative, helping to exclude macular or lichen amyloidosis. Periodic Acid-Schiff with and without digestion was negative for lipoid proteinosis, which can also have perivascular dermal and mucosal deposits of eosinophil amorphous material.

Ongoing work up further revealed the following: elevated immunoglobulin G (3412 mg/dL; normal range 600-1640), low immunoglobulin A (33 mg/dL; normal range 47-310) quantitative kappa and quantitative lambda of 1090 mg/dL and 22 mg/dL, respectively, with a kappa/lambda ration of 49.55 (normal range 1.29-2.55). Serum protein electrophoresis showed a restricted band (M-spike) migrating in the gamma globulin region; subsequent immunofixation showed an IgG kappa monoclonal gammopathy with an additional abnormal kappa free light chain present. No abnormal peaks were found on urine protein electrophoresis, although 24-h urine protein was elevated at 745 mg/d. The patient underwent a left iliac bone marrow biopsy for evaluation, which identified a kappa-restricted plasma cell neoplasm, constituting 30%-40% of cellularity, and negative for amyloid. Plasma cell FISH detected duplication of chromosome 1q and gain of chromosomes 5, 9, 15. Peripheral blood smear identified early rouleaux formation.

Correlation of the biopsies to the patient’s clinical presentation was crucial to accurate diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis. When stained with Congo red stain, all skin and gastrointestinal biopsies showed the pink amorphous material to be apple green birefringent under polarized light. A diagnosis of amyloidosis was made, and amyloid typing by mass spectrometry confirmed kappa light chain type amyloidosis.

Due to hypotension on initial evaluation in the emergency department, he received IV fluid and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Given our differential included sepsis, he was started on empiric antibiotics, which were discontinued after negative blood cultures and stabilization of blood pressure. He received midodrine for symptomatic orthostatic hypotension. Hemoglobin dropped to 6.7 g/dL, requiring multiple blood product transfusions throughout admission to maintain hemoglobin goal of 7 mg/dL. He received electrolyte, folate, and thiamine supplementation during admission. He was scheduled for outpatient follow up with hematology and oncology for initiation of amyloidosis treatment.

The patient was stabilized and discharged home, however, he returned to the emergency department soon after with worsening shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and fatigue. The patient was found to be hypotensive to 83/53 mmHg and was admitted to ICU with work up and treatment for bacteremia and septic shock. He was started on treatment for systemic amyloidosis with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone. He was stabilized, discharged, and continued treatment for amyloidosis outpatient.

Reported is a patient presenting with diarrhea, hematochezia, weight loss, nausea and new onset petechial rash, with an initial diagnosis of Crohn disease based on a colonoscopy at a community hospital. The patient’s worsening symptoms prompted presentation to our institution’s emergency department with admission and further work up. A diagnosis of AL amyloidosis was made after the patient presented in hypotensive shock and underwent fat pad biopsy with amyloid staining. An underlying plasma cell neoplasm was confirmed with bone marrow biopsy.

Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic amyloidosis is common, but is often subclinical or presenting as vague and nonspecific symptoms[3]. It is rare for gastrointestinal symptoms to be the main presenting symptom in patients with systemic amyloidosis, causing it to be undiagnosed until late-stage disease[3,15]. Gastrointestinal involvement in amyloidosis is defined as the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms with biopsy verification of amyloid. In gastrointestinal amyloidosis, clinical presentation could include abdominal pain, nausea, weight loss, malabsorption, and bleeding[16].

Upon extensive chart review, seven months prior the patient presented to an outpatient family practice clinic with new onset diarrhea and a few episodes of intermittent scant hematochezia. He denied dyspnea, weight loss, fatigue, or rash at that time. At that time, the differential diagnosis included hemorrhoids, diverticulosis, or malignancy. Vital signs were stable, complete blood count showed Hgb 13.6 g/dL (reference range 13.0-16.0 g/dL) and caseinomacropeptide within normal limits with the exception of elevated total protein at 8.6 (reference range 6.0-8.3 g/dL). He was referred for a colonoscopy which was not completed at that time. This appears to be the first presentation of the patient’s underlying amyloidosis, and his symptoms progressively worsened after this initial office visit. Consistent with other reports in the literature, the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis in this patient was made after presentation with advanced, late stage disease with multi-organ system involvement. Interestingly to this case, worsening gastrointestinal symptoms and a new petechial rash were the primary symptoms of AL amyloidosis that motivated reconsideration of the initial diagnostic impression of Crohn disease. A multidisciplinary approach culminated in a fat pad biopsy to secure the diagnosis of systemic AL amyloidosis as the etiology of the patient’s gastrointestinal symptoms.

Endoscopy findings of amyloidosis have been reported as erythema, erosions, ulcerations, friability, polypoid protrusions and submucosal hematomas[17]. If AL amyloid deposition is within blood vessels vessel wall fragility, manifests as “pinch purpura” in cutaneous amyloidosis or as erythema with friability and focal hemorrhage in the tubular gastrointestinal tract. Previous studies have found endoscopic findings such as submucosal hematomas to be highly suggestive of AL amyloidosis, requiring biopsy and Congo red staining to confirm[17]. When amyloid is deposited as a nodule or mass-like lesion, these symptoms are usually not seen. This can also be a pattern of deposition in AL amyloidosis.

Prevalence of AL amyloidosis is increasing, with a rise from 15.5 to 40 cases per million over a 9-year period[5] underscoring the importance of early recognition and treatment. For patients with persistent gastrointestinal symptoms, weight loss, evidence of malabsorption and nonspecific endoscopic findings, a diagnosis of amyloidosis should be considered and biopsy with Congo red staining performed. It is critically important to diagnose and treat amyloidosis early to prevent severe morbidity, as in this case, and mortality.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Di Meglio L, Italy; Vyshka G, Albania S-Editor: Wang DM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang DM

| 1. | Hazenberg BP. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:583-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1350] [Cited by in RCA: 1342] [Article Influence: 61.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sattianayagam PT, Hawkins PN, Gillmore JD. Systemic amyloidosis and the gastrointestinal tract. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:608-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alshehri SA, Hussein MRA. Primary Localized Amyloidosis of the Intestine: A Pathologist Viewpoint. Gastroenterology Res. 2020;13:129-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Quock TP, Yan T, Chang E, Guthrie S, Broder MS. Epidemiology of AL amyloidosis: a real-world study using US claims data. Blood Adv. 2018;2:1046-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lu R, Richards TA. AL Amyloidosis: Unfolding a Complex Disease. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2019;10:813-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Palladini G, Merlini G. What is new in diagnosis and management of light chain amyloidosis? Blood. 2016;128:159-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kastritis E, Dimopoulos MA. Recent advances in the management of AL Amyloidosis. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:170-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Muchtar E, Gertz MA, Kyle RA, Lacy MQ, Dingli D, Leung N, Buadi FK, Hayman SR, Kapoor P, Hwa YL, Fonder A, Hobbs M, Gonsalves W, Kourelis TV, Warsame R, Russell S, Lust JA, Lin Y, Go RS, Zeldenrust S, Rajkumar SV, Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A. A Modern Primer on Light Chain Amyloidosis in 592 Patients With Mass Spectrometry-Verified Typing. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:472-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cowan AJ, Skinner M, Seldin DC, Berk JL, Lichtenstein DR, O'Hara CJ, Doros G, Sanchorawala V. Amyloidosis of the gastrointestinal tract: a 13-year, single-center, referral experience. Haematologica. 2013;98:141-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lachmann HJ, Goodman HJ, Gilbertson JA, Gallimore JR, Sabin CA, Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN. Natural history and outcome in systemic AA amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2361-2371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 771] [Cited by in RCA: 647] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bahlis NJ, Lazarus HM. Multiple myeloma-associated AL amyloidosis: is a distinctive therapeutic approach warranted? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:7-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kumakiri M, Hashimoto K. Histogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: sequential change of epidermal keratinocytes to amyloid via filamentous degeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:150-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cai D, Li Y, Zhou C, Jiang Y, Jiao J, Wu L. Comparative proteomics analysis of primary cutaneous amyloidosis. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:3004-3012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Menke DM, Kyle RA, Fleming CR, Wolfe JT 3rd, Kurtin PJ, Oldenburg WA. Symptomatic gastric amyloidosis in patients with primary systemic amyloidosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:763-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rowe K, Pankow J, Nehme F, Salyers W. Gastrointestinal Amyloidosis: Review of the Literature. Cureus. 2017;9:e1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | James DG, Zuckerman GR, Sayuk GS, Wang HL, Prakash C. Clinical recognition of Al type amyloidosis of the luminal gastrointestinal tract. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:582-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |