Published online Sep 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i27.9936

Peer-review started: May 21, 2022

First decision: June 27, 2022

Revised: July 2, 2022

Accepted: August 11, 2022

Article in press: August 11, 2022

Published online: September 26, 2022

Processing time: 110 Days and 23.2 Hours

All drugs have the potential to cause drug-induced lung injury both during and after drug administration. Acetaminophen has been reported to cause drug-induced lung injury, although this is extremely rare. Herein, we present an extremely rare case of acetaminophen-induced pneumonia.

A healthy 35-year-old Japanese woman visited a neighborhood clinic with complaints of fever and malaise following a tick bite. Her treatment included 1,500 mg acetaminophen (Caronal®) and subsequently minocycline (200 mg) and acetaminophen (2,000 mg; Caronal®) daily when her condition did not improve; the patient was eventually hospitalized. The patient’s chest computed tomography (CT) revealed consolidation and ground-glass opacities in the right middle and lower lobes. Minocycline was shifted to sulbactam/ampicillin. However, her fever did not improve during follow-up, and her chest CT revealed extensive ground-glass opacities in the right middle and lower lobes and thick infiltrative shadows in the bilateral basal areas. Drug-induced lung injury was suspected; hence, acetaminophen was discontinued. The fever resolved immediately, and inflammatory response and respiratory imaging findings improved. A drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation test was performed against acetaminophen (Caronal®), and significant proliferation of lymphocytes was noted only for acetaminophen (stimulation index, 2.1).

Even common drugs such as over-the-counter drugs can cause drug-induced lung damage.

Core Tip: We present an extremely rare case of acetaminophen-induced lung injury. Even common drugs, including over-the-counter drugs, can cause lung injury, warranting consideration when evaluating emergent lung disease.

- Citation: Fujii M, Kenzaka T. Drug-induced lung injury caused by acetaminophen in a Japanese woman: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(27): 9936-9944

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i27/9936.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i27.9936

All drugs have the potential to cause drug-induced lung injury both during and after drug administration. Although this is extremely rare, acetaminophen can also reportedly cause drug-induced lung injury[1]. Drug-induced lung disease is associated with various pathophysiologic and clinical presentations and syndromes. However, certain clinical patterns of pneumonia are likely to occur with specific types of drugs, as previously reported[2]. The drug provocation test is the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity[3]. However, this test is associated with a high risk of severe side effects; therefore, its use is controversial.

In clinical practice, resolution of symptoms after suspected drug exposure cessation is usually sufficient for diagnosis without the need for rechallenge[4]. The diagnosis of drug-induced lung injury is based on a combination of information, including symptoms, physical examinations, drug intake and medical history, and imaging and pathological findings[5]. Acetaminophen-induced lung injury generally presents as a clinical form of drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia[1,2]. Acetaminophen is one of the most frequently used drugs, and a few studies have reported acetaminophen-induced lung injury. Herein, we describe the clinical characteristics of acetaminophen-induced pneumonia in a Japanese woman.

A healthy 35-year-old Japanese woman visited a neighborhood clinic 7 d before hospitalization with complaints of fever and malaise.

She was bitten by a tick while cleaning her house 9 d before hospitalization.

Nothing in particular.

Her personal and family history was unremarkable. On admission, she had no history of smoking or allergies as well.

On physical examination at admission, the patient’s temperature was 37.3 °C, blood pressure was 93/52 mmHg, pulse rate was 72 beats/min, respiration rate was 16 breaths/min, and peripheral capillary oxygen saturation level was 96% (room air).

Respiratory and cardiovascular tests yielded clear results. Lymph nodes were palpable in the right axilla with two erythematous patches in the surrounding area.

The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count was 8310/mm3, with 86.5% neutrophils, 11.7% lymphocytes, and 0.0% eosinophils. Her C-reactive protein level was 31.65 mg/dL. Tests for antibodies against Orientia tsutsugamushi showed negative findings. Blood culture results were also negative. Urine culture revealed Enterococcus species and coagulase-negative Staphylococci (Table 1).

| Parameter | Recorded value | Standard range |

| White blood cell count | 8310/µL | 4500-7500/µL |

| Neutrophil | 86.50% | |

| Lymphocyte | 11.70% | |

| Monocyte | 1.70% | |

| Eosinophils | 0.00% | |

| Hemoglobin | 11.8 g/dL | 11.3-15.2 g/dL |

| Platelet count | 23.2 × 103/µL | 13-35 × 103/µL |

| Total protein | 6.9 g/dL | 6.9-8.4 g/dL |

| Albumin | 3.5 g/dL | 3.9-5.1 g/dL |

| Total bilirubin | 0.7 mg/dL | 0.2-1.2 mg/dL |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 31 U/L | 11-30 U/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 26 U/L | 4-30 U/L |

| Lactase dehydrogenase | 368 U/L | 109-216 U/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 9.6 mg/dL | 8-20 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.5 mg/dL | 0.63-1.03 mg/dL |

| Sodium | 135 mEq/L | 135-145 mEq/L |

| Potassium | 4.2 mEq/L | 3.6-5.2 mEq/L |

| Chlorine | 98 mEq/L | 98-108 mEq/L |

| C-reactive protein | 31.65 mg/L | ≤ 1.0 mg/L |

| Procalcitonin | 0.66 ng/mL | ≤ 0.3 ng/mL |

| KL-6 | 205 U/mL | ≤ 500 U/mL |

| Surfactant protein A | 105.9 ng/mL | ≤ 43.8 ng/mL |

| Surfactant protein D | 105.3 ng/mL | ≤ 110 ng/mL |

| C3 | 136 mg/dL | 86-160 mg/dL |

| C4 | 28.7 mg/dL | 17-45 mg/dL |

| IgG | 1137 mg/dL | 870-1700 mg/dL |

| IgA | 193 mg/dL | 110-410 mg/dL |

| IgM | 134 mg/dL | 35-220 mg/dL |

| ACE | 15.2 U/mL | 8.3-21.4 U/mL |

| Antinuclear antibody | < 40 | < 40 |

| RF | < 3 U/mL | 0-15 U/mL |

| Anti-CCP antibody | 0.8 U/mL | < 5 U/mL |

| Anti-Ro/SS-A antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-La/SS-B antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Jo-1 antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-ARS antibody | Negative | Negative |

| PR3-ANCA | Negative | Negative |

| MPO-ANCA | Negative | Negative |

| Orientia tsutsugamushi Karp IgG | < 10 | < 10 |

| Orientia tsutsugamushi Karp IgM | < 10 | < 10 |

| Orientia tsutsugamushi Kato IgG | < 10 | < 10 |

| Orientia tsutsugamushi Kato IgM | < 10 | < 10 |

| Orientia tsutsugamushi Gilliam IgG | < 10 | < 10 |

| Orientia tsutsugamushi Gilliam IgM | < 10 | < 10 |

| C. pneumoniae IgG | Negative | Negative |

| C. pneumoniae IgA | Negative | Negative |

| CMV-IgG | 199.7 | 0.0-1.0 |

| CMV-IgM | < 0.85 | 0-0.7 |

| M. pneumoniae PCR of the sputum | Negative | Negative |

| Urine Legionella antigen testing | Negative | Negative |

| Beta-D-glucan assay | 9.0 pg/mL | |

| Aspergillus IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Trichosporon asahii antibody | Negative | Negative |

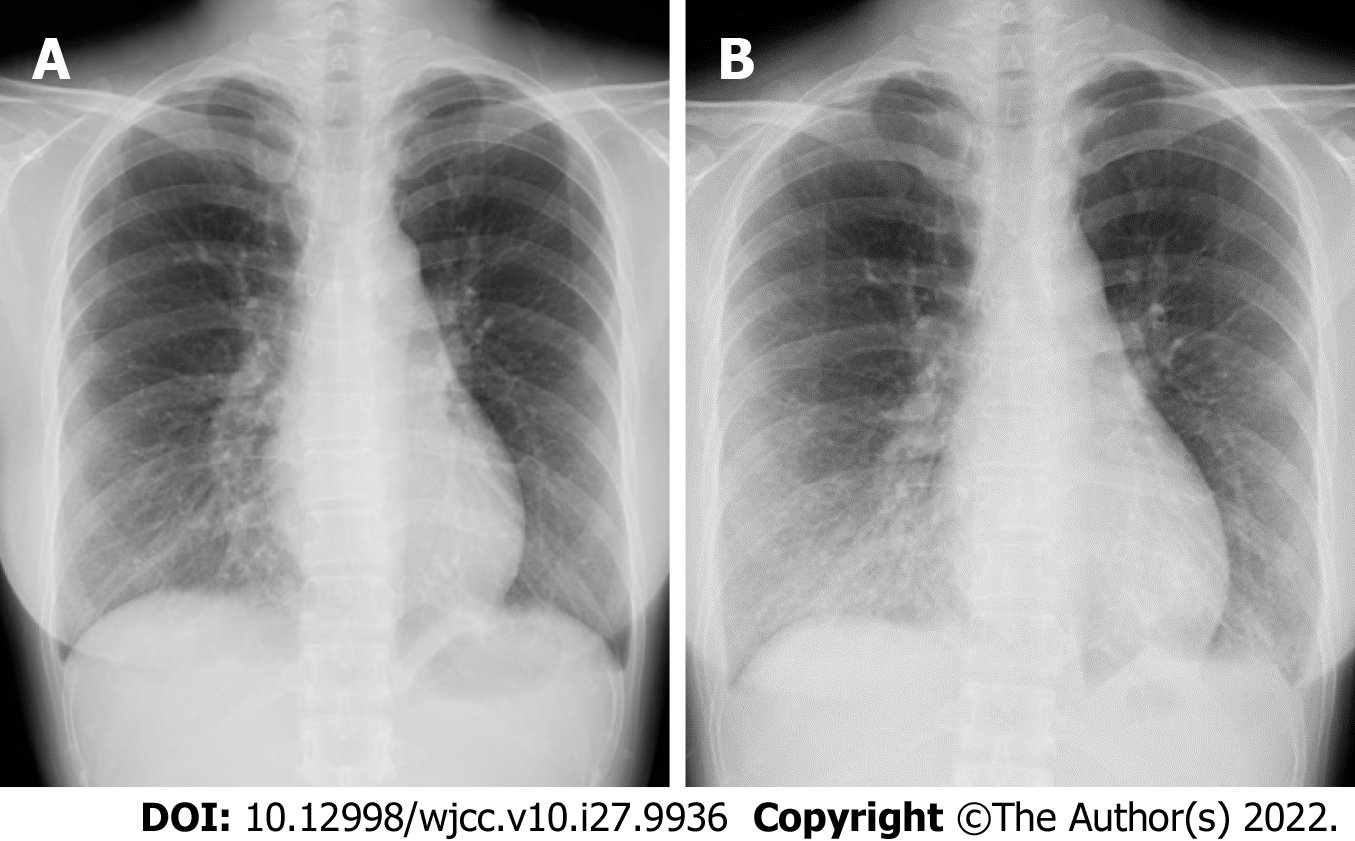

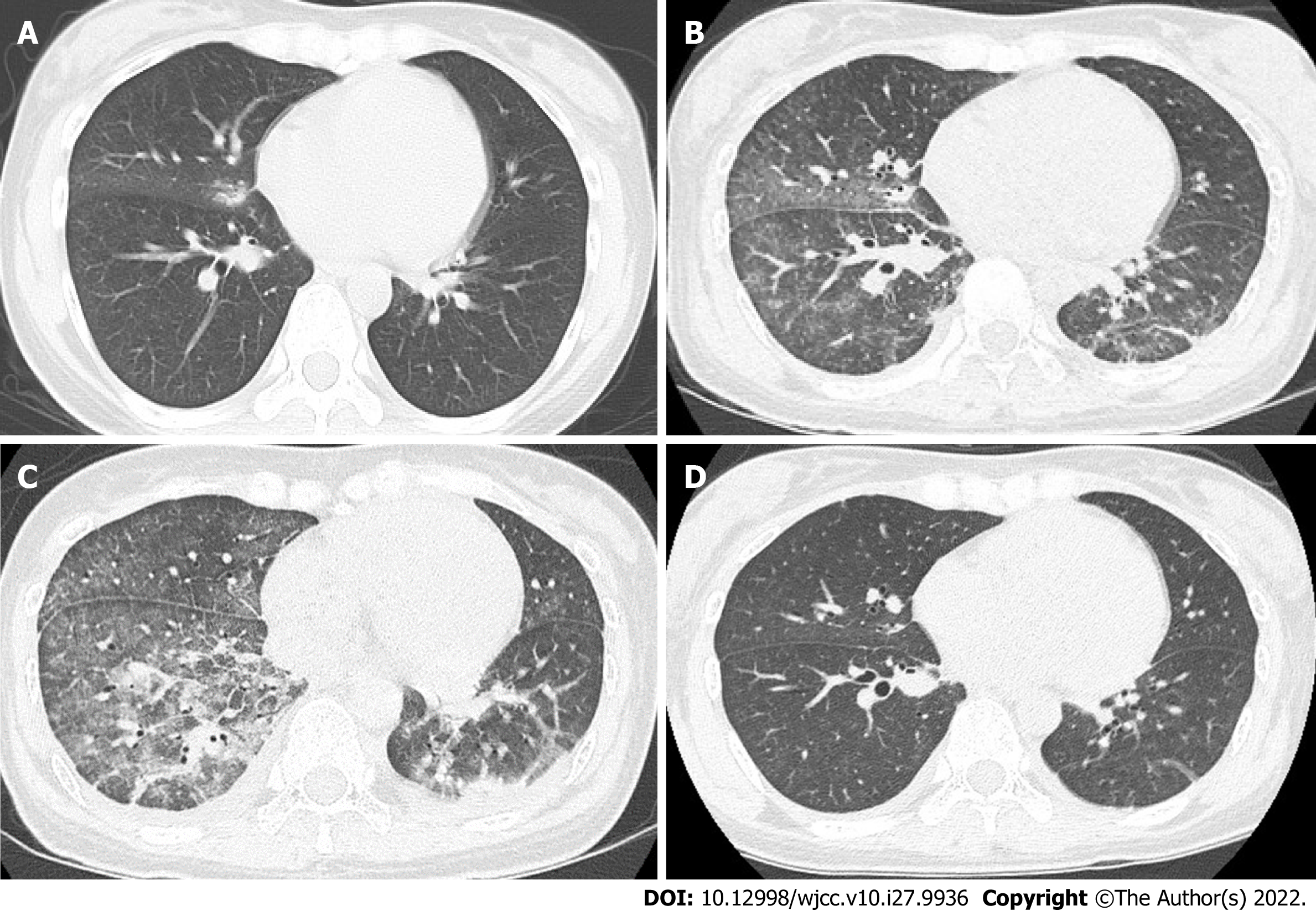

Chest radiography revealed interstitial shadows in the right lower lung (Figure 1A). Physical examination revealed a palpable right axillary lymph node; therefore, thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed for deep lymph node evaluation. Chest CT revealed consolidation and ground-glass opacities in the right middle and lower lobes (Figure 2A). Minocycline was discontinued because of the low risk of rickettsial infection. Acetaminophen (Caronal®) 2000 mg was administered orally, and acetaminophen (Acelio®) 500 mg was administered intravenously for symptomatic treatment.

We suspected pyelonephritis; based on the antimicrobial susceptibility of urine culture results, we administered sulbactam/ampicillin 3 g every 6 h for 3 d. However, a fever of > 38 °C persisted. On day 4 of hospitalization, repeat chest radiography revealed worsening of interstitial shadows in the right lower lung (Figure 1B), and chest CT revealed extensive ground-glass opacities mainly in the right middle and lower lobes and thick infiltrative shadows in the bilateral basal areas. In addition, thickening of the interlobular septum, bronchovascular bundles, and bilateral pleural effusions suggested eosinophilic pneumonia or organizing pneumonia (Figure 2B and C).

We suspected atypical pneumonia or interstitial pneumonia and investigated the patient for infections and collagen diseases; however, serological tests for common causative agents of atypical pneumonia and autoimmune disease-associated autoantibodies revealed negative results (Table 1).

The patient was treated with acetaminophen 1500 mg (Caronal®); however, her condition did not improve. Three d before hospitalization, she presented with a fever of 38 °C and a lack of appetite. We suspected rickettsial infection at this time and initiated daily administration of minocycline (200 mg) and acetaminophen (2,000 mg; Caronal®); however, her condition did not improve; therefore, she was admitted to our hospital.

Atypical pneumonia was considered in the differential diagnosis, and azithromycin 500 mg was administered as the first dose, followed by 250 mg every 24 h for 5 d after the second dose. Since we suspected drug-induced lung injury, acetaminophen was discontinued and replaced with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, resulting in resolution of fever on day 6 of hospitalization and improvement in inflammatory response and pulmonary imaging findings, without immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory therapy, on day 10 of hospitalization (Figure 2D). Hypoxemia was not observed during hospitalization; therefore, the drug was discontinued, and the patient was discharged on day 13 of hospitalization. The drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation test (DLST) was performed against acetaminophen (Caronal®) and minocycline post-discharge, and negative results were obtained for minocycline, with significant proliferation of lymphocytes noted only for acetaminophen and a stimulation index of 2.1. The sensitivity of the DLST is reported to be 60%-70%, and its specificity is 85%; however, false-positive results have also been reported; therefore, the DLST was only intended to assist the diagnostic process[6,7].

The diagnostic criteria for drug-induced lung injury outlined by Camus et al[2] are as follows: (1) Correct identification of the drug; (2) Singularity of the drug; (3) Temporal eligibility; (4) Characteristic clinical, imaging, bronchoalveolar lavage, and pathologic patterns of reaction to the specific drug; and (5) Exclusion of other causes of interstitial lung disease (ILD). The patient was healthy, had no history of ILD, and had a new history of acetaminophen and minocycline exposure. Minocycline was administered for 3 d and discontinued on admission. The patient developed drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia-like imaging findings on day 4 of hospitalization. The imaging findings worsened gradually after discontinuation of minocycline until day 4 of hospitalization, suggesting that minocycline was unlikely to have influenced the patient’s disease. On the other hand, symptoms and imaging findings rapidly improved after discontinuation of acetaminophen on day 4 of hospitalization. In addition, other potential causes of ILD, such as infections and collagen diseases, were excluded. Although the drug provocation test was not performed, all diagnostic criteria were met, and acetaminophen-induced pneumonia was diagnosed. No recurrence of ILD was observed in the last 4 years since the patient first visited our clinic.

We present an extremely rare case of acetaminophen-induced lung injury. Although the drug provocation test was not performed in this case, we diagnosed acetaminophen-induced lung injury based on the history of drug administration, clinical course, and DLST results. The imaging findings suggested eosinophilic pneumonia; however, since bronchoalveolar lavage was not performed, the diagnosis could not be confirmed. Acetaminophen is an extremely rare causative agent of drug-induced pneumonia[1,2,8,9]. Acetaminophen-induced lung injury has been reported in 16 patients, excluding the patient in this case, as indexed in PubMed (Table 2)[10-24]. Among the 17 patients, including our patient, 12 (70.6%) were female patients, five (29.4%) were male patients, and 16 (94.1%) were Japanese patients. Only one case of a Caucasian patient has been reported in another country. The patients’ median age was 64 years (interquartile range [IQR], 45-72 years). Acetaminophen and over-the-counter drugs containing acetaminophen were the causative agents in nine (52.9%) and eight (47.1%) patients, respectively. Seven (41.1%) patients met the diagnostic criteria for drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia[1,8]. The median time (in d) between drug exposure and the onset of respiratory symptoms was 5 d (IQR, 3-11 d); the onset was often relatively short-lived after the initiation of medication. In all patients, the causative drug was discontinued at the start of treatment, and the condition of four (23.5%) patients improved with discontinuation of the drug alone, while 13 (76.5%) patients required corticosteroids. Two patients required ventilation management, and all patients were discharged with good outcomes.

| Case | Sex | Age (years) | Ethnicity | Drugs | Symptoms | Time between drug use and presentation (d) | Time between initial diagnosis and drug discon | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. |

| 1 | Female | 20 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Norshin®) | Fever, cough, and dyspnea | 2 | 0 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Kitaguchi et al[10], 1992 |

| 2 | Female | 63 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Caronal®) | Cough and dyspnea | 8 | 10 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Kudeken et al[11], 1993 |

| 3 | Male | 45 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (PL Combination Granules®) | Fever, cough, and diarrhea | 4 | 0 | Drug discontinuation | Disease resolution | Nakatsumi et al[12], 1994 |

| 4 | Male | 75 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Pabron gold®/Pabron S®) | Fever and dyspnea | 3 | 0 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Nomura et al[13], 1997 |

| 5 | Male | 57 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (PL Combination Granules® /Shin Lulu A Tablets®) | Fever, cough, and dyspnea | 11 | 8 months | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Respiration and disease resolution | Kawano et al[14], 1997 |

| 6 | Female | 64 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Caronal®) | Fever, cough, and dyspnea | 19 | 8 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Akashi et al[15], 1997 |

| 7 | Female | 70 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Caronal®) | Fever, cough, and dyspnea | 6 | 5 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Nakajima et al[16], 1998 |

| 8 | Female | 49 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Benza Block SP®) | Fever and dyspnea | 5 | 5 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Nakajima et al[16], 1998 |

| 9 | Male | 72 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (PL Combination Granules®) | Fever and dyspnea | 1 | 0 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Respiration and Disease resolution | Ikeuchi et al[17], 2000 |

| 10 | Male | 31 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (PL Combination Granules®) | Fever and cough | 13 | 31 | Drug discontinuation | disease resolution | Hiramatsu et al[18], 2002 |

| 11 | Female | 68 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (PL Combination Granules®) | Fever, cough, and dyspnea | 6 | 0 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids, Cyclosporine | Disease resolution | Nakayama et al[19], 2006 |

| 12 | Female | 41 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Ibuprofen®/Caronal®) | Fever, cough, and dyspnea | 3 | 0 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Anan et al[20], 2009 |

| 13 | Female | 84 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Shin Lulu A Tablets s®) | Fever, cough, and dyspnea | 5 | 0 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Kato et al[21], 2010 |

| 14 | Female | 80 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Caronal®) | Fever and dyspnea | 15 | 0 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Sasaki et al[22], 2014 |

| 15 | Female | 68 | Caucasian | Acetaminophen (Caronal®) | Cough and dyspnea | Months | Not specified | Drug discontinuation | Disease resolution | Saint-Pierre et al[23], 2016 |

| 16 | Female | 79 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Caronal®) | Dyspnea | 2 | 0 | Drug discontinuation; Corticosteroids | Disease resolution | Ueda et al[24], 2019 |

| Present case | Female | 35 | Japanese | Acetaminophen (Caronal®) | Fever | 4 | 11 | Drug discontinuation | Disease resolution | - |

There are several reasons for the relatively high number of reports of acetaminophen-induced lung injury in Japan. First, racial differences may exist, such that drug-induced lung injury has been associated with ethnicity. The incidence and mortality rates of drug-induced lung injuries are higher in Japan than in other countries[5]. These ethnicity-based differences suggest possible variations in the genes related to lung fragility in Japanese patients[25]. The MUC4 gene is suspected to be the causative gene and remains under investigation. Furthermore, a large number of CT examinations than those performed in other countries[26] may affect these rates.

Several drugs can induce lung injury both during and after administration[2]. Acetaminophen is a frequently prescribed drug in clinical practice and is a constituent of many medical and over-the-counter drugs. The incidence of drug-induced lung injury has been reported for acetaminophen alone and for acetaminophen-containing combination drugs and over-the-counter drugs. In previous reports, eight (47.1%) patients were suspected of having acetaminophen-induced lung injury at the time of initial diagnosis, and the drug was discontinued[24]. The eight patients, including the patient in this case, were not diagnosed with acetaminophen-induced lung injury at the time of initial diagnosis and continued to use it. Acetaminophen is not easily identified as a cause of drug-induced lung injury because of the rarity of the injury and the tendency of patients to withhold information on frequently or recently used drugs. In many cases, patients recover spontaneously on discontinuing the drug; however, a severe course is noted in some cases. Therefore, in this case, acetaminophen should have been discontinued at an early stage. It is important to remember that even common drugs, including over-the-counter drugs, can cause drug-induced lung injury.

We have presented an extremely rare case of acetaminophen-induced lung injury. Even common drugs, including over-the-counter drugs, can cause lung injury and must be considered when evaluating emergent lung disease.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bao S, Australia; Jian X, China S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Allen JN. Drug-induced eosinophilic lung disease. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:77-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Camus P, Fanton A, Bonniaud P, Camus C, Foucher P. Interstitial lung disease induced by drugs and radiation. Respiration. 2004;71:301-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Aberer W, Bircher A, Romano A, Blanca M, Campi P, Fernandez J, Brockow K, Pichler WJ, Demoly P; European Network for Drug Allergy (ENDA); EAACI interest group on drug hypersensitivity. Drug provocation testing in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity reactions: general considerations. Allergy. 2003;58:854-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 538] [Cited by in RCA: 543] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | De Giacomi F, Vassallo R, Yi ES, Ryu JH. Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia. Causes, Diagnosis, and Management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:728-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ushiki A, Hanaoka M. Clinical characteristics of DLI: What are the clinical features of DLI? In: Hanaoka M, Nakamura H, Aoshiba K, editors. Drug-Induced Lung Injury. Respiratory Disease Series: Diagnostic Tools and Disease Managements. Singapore: Springer, 2018 [cited 20 April 2022]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-10-4466-3. |

| 6. | Pichler WJ, Tilch J. The lymphocyte transformation test in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2004;59:809-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ono E, Miyazaki E, Matsuno O, Nureki S, Okubo T, Ando M, Kumamoto T. Minocycline-induced acute eosinophilic pneumonia: controversial results of lymphocyte stimulation test and re-challenge test. Intern Med. 2007;46:593-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Solomon J, Schwarz M. Drug-, toxin-, and radiation therapy-induced eosinophilic pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:192-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bartal C, Sagy I, Barski L. Drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia: A review of 196 case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e9688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kitaguchi S, Miyazawa T, Minesita M, Doi M, Takahashi K, Yamakido M. [A case of acetaminophen-induced pneumonitis]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;30:1322-1326. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kudeken N, Kawakami K, Kakazu T, Takushi Y, Fukuhara H, Nakamura H, Kaneshima H, Saito A, Toda T. A case of acetaminophen-induced pneumonitis. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1993;31:1585-1590. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Nakatsumi Y, Nakatsumi T, Bandou T, Kumabasiri I, Araki I, Ueno T, Nomura M, Fujimura M, Matsuda T. A case of pneumonitis induced by PL granules. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1994;32:1209-1212. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Nomura M, Fujimura M, Matsuda T, Kitagawa M. Drug-induced pneumonitis associated PABRON-GOLD. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;35:72-76. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kawano T, Ogushi F, Maniwa K, Nakamura Y, Haku T, Sone S. A case of rheumatoid lung exacerbated by acetaminophen-induced pneumonitis. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;35:1113-1118. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Akashi S, Tominaga M, Naitou K, Fujisawa N, Nakahara Y, Hiura K, Hayashi S. Two cases of acetaminophen-induced pneumonitis. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1997;35:974-979. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Nakajima M, Yoshida K, Miyashita N, Niki Y, Matsushima T. Acetaminophen-induced pneumonitis. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;36:973-977. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ikeuchi H, Sando Y, Tajima S, Sato M, Hosono T, Maeno T, Maeno Y, Suga T, Kurabayashi M, Nagai R. PL granule-induced pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2000;38:682-686. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Hiramatsu K, Takeda Y, Yamauchi Y, Suzuki T, Kudo K. A case of eosinophilic pneumonia induced by Pelex granule. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2002;40:220-224. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Nakayama S, Mukae H, Ishimatsu Y, Sugiyama K, Ide M, Ishimoto H, Hisatomi K, Ishii H, Abel K, Ozono Y, Kohno S. A case of rheumatoid lung complicated by SELAPINA-induced pneumonia. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2006;44:858-863. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Anan E, Shirai R, Kai N, Ishii H, Hirata N, Kishi K, Tokimatsu I, Nakama K, Hiramatsu K, Kadota J. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia caused by several drugs including ibuprofen. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2009;47:443-447. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kato H, Ogasawara T, Kimura R, Paku C, Wakayama H, Suzuki M. A case of drug-induced pneumonitis due to a cold remedy. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2010;48:619-624. [PubMed] |

| 22. |

Sasaki A, Murata K, Sato Y, Wada A, Takamori M.

A case of drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia caused by acetaminophen that was diagnosed by accidental readministration of the combination remedy for colds. |

| 23. | Saint-Pierre MD, Moran-Mendoza O. Acetaminophen Use: An Unusual Cause of Drug-Induced Pulmonary Eosinophilia. Can Respir J. 2016;2016:4287270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. |

Ueda T, Araya T, Uchida Y, Kimura H, Kasahara K, Kita T.

A case of acetaminophen-induced eosinophilic pneumonia. |

| 25. | Anan K, Ichikado K, Kawamura K, Johkoh T, Fujimoto K, Suga M. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of drug-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome compared with non-drug-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a single-centre retrospective study in Japan. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | OECD Health Statistics 2021. [cited 20 April 2022]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm. |