Published online Sep 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i27.9897

Peer-review started: May 6, 2022

First decision: May 30, 2022

Revised: June 25, 2022

Accepted: August 16, 2022

Article in press: August 16, 2022

Published online: September 26, 2022

Processing time: 132 Days and 12 Hours

Aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) is the most common congenital anomaly of the aortic arch. When patients having such anomalies receive transradial intervention (TRI), aortic dissection (AD) may occur. Herein, we discuss a case of iatrogenic type B AD occurring during right TRI in an ARSA patient, that was later salvaged by percutaneous angioplasty.

A 73-year-old man presented to our hospital with intermittent chest pain. Coronary computed tomography (CT) angiography revealed significant stenosis in the left anterior descending artery. Diagnostic coronary angiography was performed via the right radial artery without difficulty. However, we were unable to advance the guiding catheter past the ostium of the right subclavian artery to the aortic arch for percutaneous coronary intervention, while the guidewire tended to go down the descending aorta. The patient suddenly complained of chest and back pain. Emergent CT aortography revealed type B AD propagating to the left renal artery (RA) with preserved renal perfusion. However, after 2 d, the patient suddenly complained of right lower limb pain where the femoral pulse was suddenly undetectable. Follow-up CT indicated further progression of dissection to the right external iliac artery (EIA) and left RA with limited flow. We performed percutaneous angioplasty of the right EIA and left RA without complications. Follow-up CT aortography at 8 mo showed optimal results.

A caution is required during right TRI in ARSA to avoid AD. Percutaneous angioplasty can be a treatment option.

Core Tip: Aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) is the most common congenital anomaly of the aortic arch. When patients having anomalies undergo transradial intervention (TRI), aortic dissection (AD) may occur. Herein, we present a case of iatrogenic type B AD occurring during right TRI in an ARSA that was treated with percutaneous angioplasty.

- Citation: Ha K, Jang AY, Shin YH, Lee J, Seo J, Lee SI, Kang WC, Suh SY. Iatrogenic aortic dissection during right transradial intervention in a patient with aberrant right subclavian artery: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(27): 9897-9903

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i27/9897.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i27.9897

Aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) is a congenital anomaly of the aortic arch. In ARSA, the right subclavian artery arises from the descending aorta and passes between the trachea and the esophagus[1]. It is observed in 2% of the general population and is more frequent in patients having Down syndrome with a prevalence of 35%[2,3]. Diverse clinical manifestation associated with ARSA have been reported, including dysphagia, dyspnea and retrosternal pain, although most patients are generally asymptomatic[4,5]. Several cases of ARSA associated with procedure-related aortic dissection (AD) treated surgically or conservatively have been reported[6]. Herein, we report a case of a patient with an incidentally found ARSA during right transradial intervention (TRI), which further resulted in iatrogenic type B AD that was further salvaged by percutaneous angioplasty.

A 73-year-old man presented to the emergency room with intermittent chest pain and shortness of breath (New York Heart Association class II).

The patient had developed chest pain and dyspnea on exertion in the past 1 mo, which had worsened for 3 d.

The patient also had a history of hypertension as well as smoking (30 pack years).

His initial blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg with a heart rate of 80 beats per minute. Room air oxygen saturation was 97%. He had a regular heartbeat without a murmur. His lung sounds were also clear. There was no abdominal tenderness or pitting edema.

Electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with T wave abnormality in leads V1 to V3 without definite ST segment elevation or depression.

Initial cardiac enzyme levels, including creatine kinase-myocardial band and troponin I were within the normal range. The serum creatinine level was normal (0.96 mg/dL).

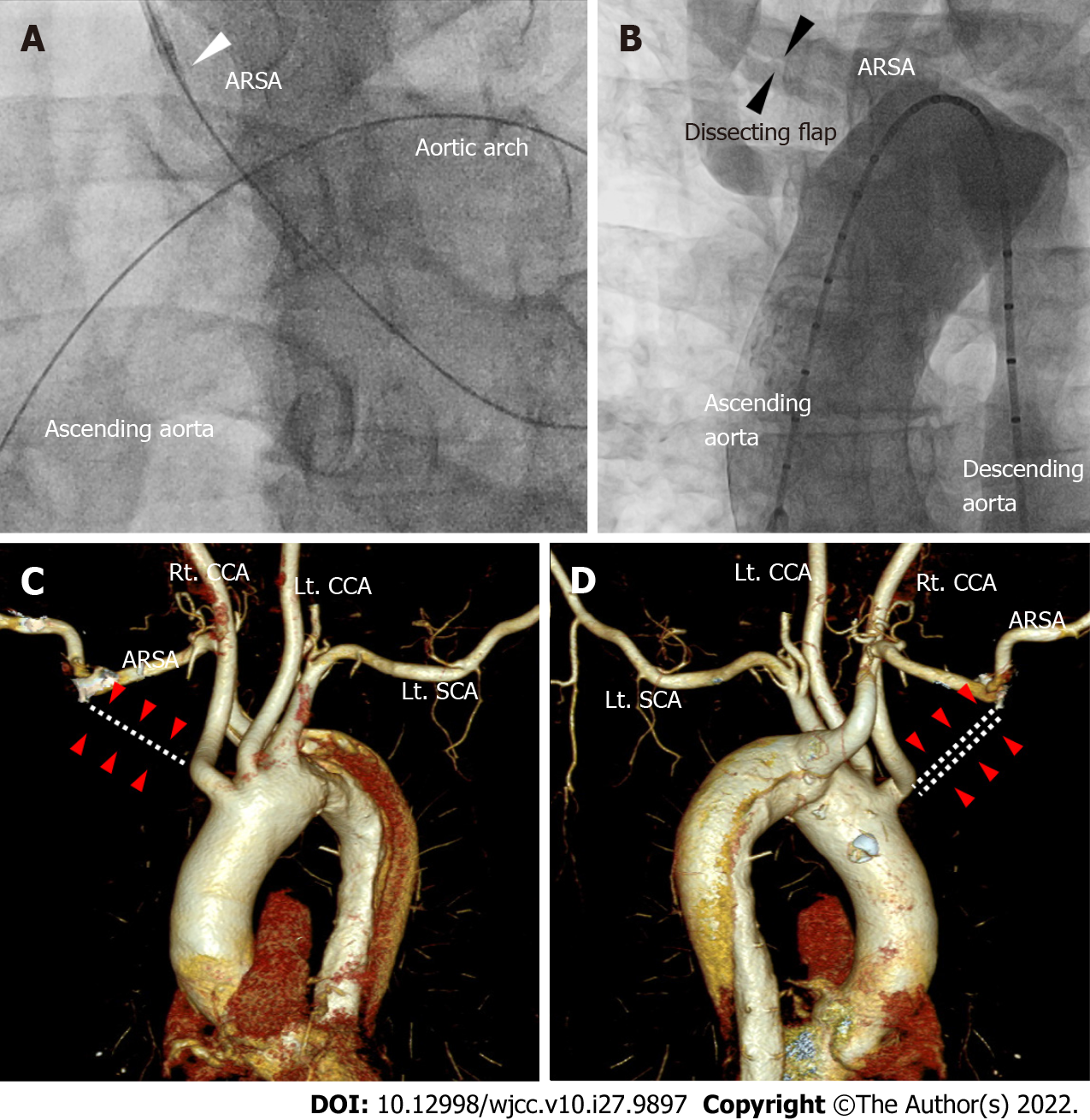

Coronary computed tomography (CT) angiography as an initial screening test revealed significant proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery stenosis. Percutaneous coronary intervention was decided. Diagnostic angiography was performed via the right radial artery, which showed 90% stenosis of the mid LAD. We re-inserted the extra backup 3.5 guiding catheter for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, we were unable to advance the catheter past the ostium of the right subclavian artery (SCA) to the ascending aorta with similar force applied to that required for the diagnostic catheter. Additionally, since the J-tip 0.035” guidewire tended to go down the descending aorta, we changed the guidewire to an angled 0.035’’ wire, which after several manipulations and additional forced pushes, appeared as though it successfully approached the ascending aorta, although an unusually large loop was formed by the guidewire (Figure 1A). The patient also suddenly complained of chest and back pain. As we suspected aortic dissection, we further performed an aortogram using a 5Fr pigtail catheter via the right femoral artery (FA) only to confirm a dissection flap of the right SCA (Figure 1B).

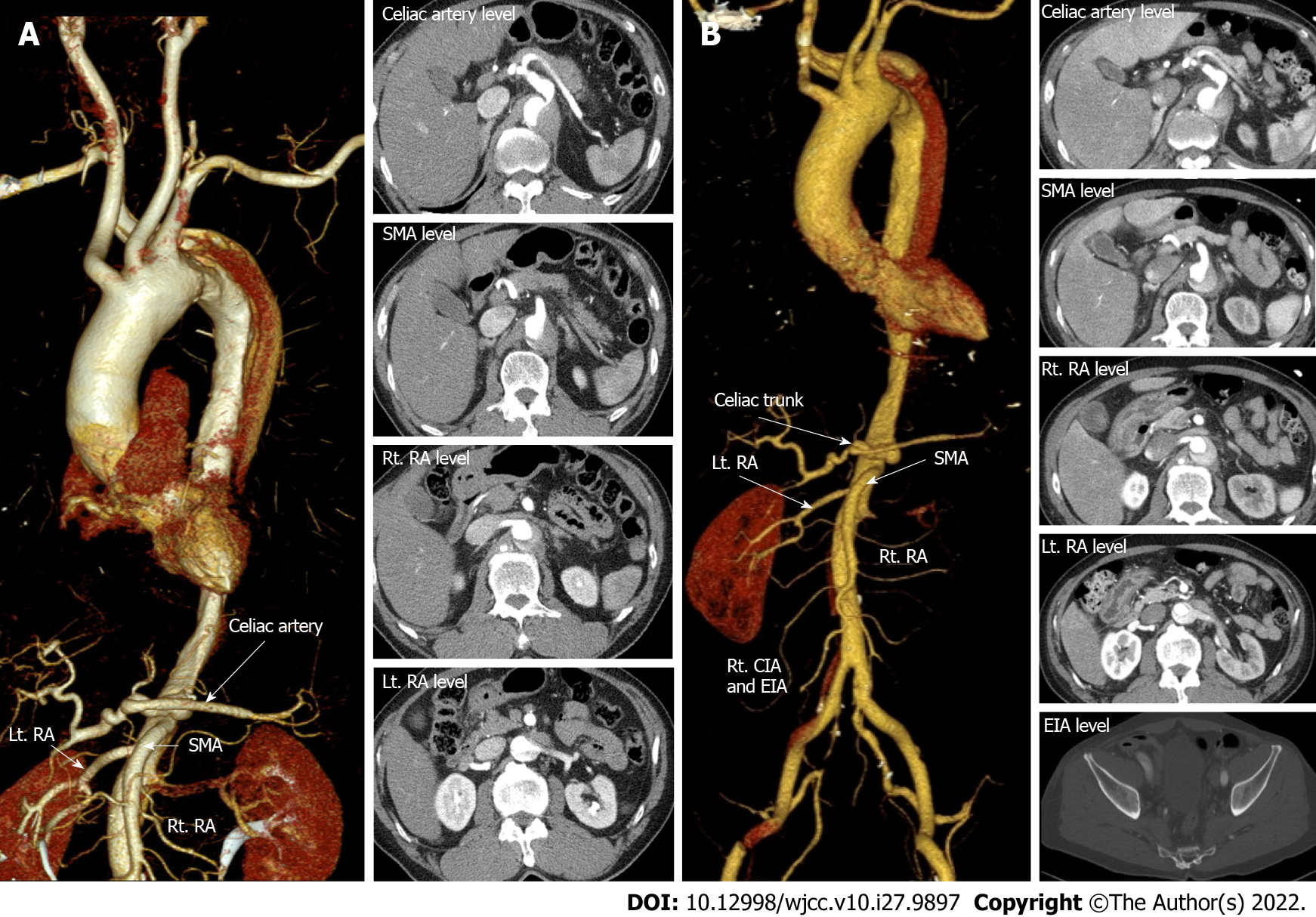

We promptly stopped the procedure and performed emergent CT aortography. The CT revealed an ARSA (Figure 1C and D) associated with type B AD originating from the proximal portion of the ARSA extending to the descending aorta down the infra-renal portion (Figure 2A). The celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and right renal artery (RA) originated from the true lumen. However, the dissection flap advanced through the left RA where the flow was preserved.

Seok In Lee, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Gil Medical Center, Gachon University College of MedicineWe consulted with the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery for type B AD. Surgical care was deferred because there was no evidence of type A AD, with preserved renal perfusion and an intact cerebral blood supply.

The final diagnosis of the present case was ARSA with iatrogenic acute type B AD during the right TRI.

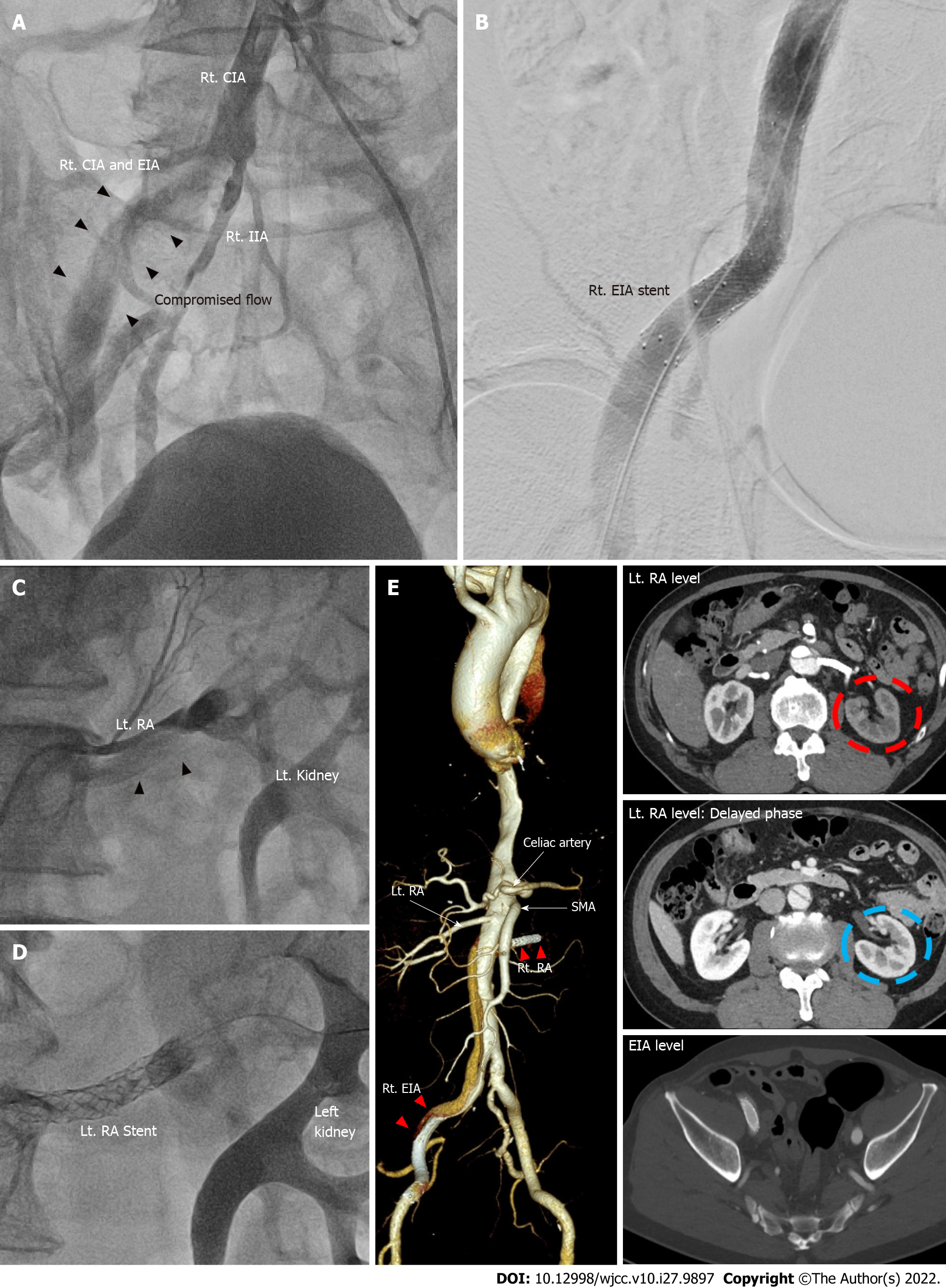

The patient received conservative management, and vital signs were closely monitored in the intensive care unit (ICU). On the second day of the ICU stay, the patient suddenly complained right lower limb pain. We immediately recognized that his right femoral pulsation had dramatically decreased and we were unable to detect any pulse. The left femoral pulse was normal. This suggested that his right femoral perfusion was probably compromised due to the propagation of type B AD. Serum creatinine level was also slightly increased (1.2 mg/dL) compared with the baseline (0.96 mg/dL). Bed side echocardiography showed no pericardial effusion or intimal flap of the ascending aorta. Follow-up CT aortography demonstrated downstream propagation of the AD into the right common iliac artery (CIA) and external iliac artery (EIA) (Figure 2B). Other branches of the abdominal aorta including the celiac trunk, SMA, inferior mesenteric artery and left CIA continued to be originated from the true lumen without flow limitation. However, the true lumen within the left RA was becoming compromised (Figure 2B). We decided to perform percutaneous transluminal angioplasty to the right EIA and left RA, because of the weakened right FA pulse and elevating creatinine levels. Right iliac catheterization was performed via contralateral femoral approach (Figure 3A), in which sluggish flow through the EIA was confirmed. The blood flow was salvaged after a 14 mm × 60 mm-sized Smart® stent (Cordis, CA, United States) was implanted to the right EIA (Figure 3B). Then left renal angioplasty was done through the left FA to the aorta using a 5Fr Judkins right 3.5 catheter (Figure 3C). After meticulously selecting the true lumen of the left RA, we inserted a 0.014-inch guidewire. A 3.5 mm × 40 mm-sized Sleek® stent (Cordis, CA, United States) was subsequently inserted into the left RA (Figure 3D). We completed the procedure after confirming that the blood flow was restored in the left RA. As the vital signs of the patient were stable, we performed PCI to the LAD without complications.

His limb pain improved immediately after the angioplasty. Although, his creatinine level increased up to 1.7 mg/dL the next day, it recovered back to the baseline level of 0.9 mg/dL 3 d post-intervention. The patient was discharged in a few days without any symptoms. Follow-up CT after eight months showed patent stents in the right EIA and left RA (Figure 3E). The patient has been uneventful for more than a year.

ARSA is the most common congenital anomaly of the aortic arch arising from the descending aorta, and typically has a retroesophageal course. Because most patients are asymptomatic, ARSA is often accidentally discovered during the procedure such as TRI[7]. The success rate of right TRI in the setting of ARSA is only 60% even in an experienced operator, because it requires drastic angulation of the catheter to approach the ascending aorta, increasing the chance of aortic injury[8]. Coronary CT may be used as a screening tool for evaluating aortic anomalies before the procedure if the CT scan covers the aortic arch[8]. Our patient had coronary CT before the TRI for evaluating the extent of coronary lesion; unfortunately, the results only covered the coronary artery but not the aortic arch. Hence, we may consider evaluating the aortic arch during coronary CT in patients scheduled for right TRI.

Previously reported cases of AD caused by ARSA were treated surgically or conservatively[7-9]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of TRI in the setting of ARSA resulting in iatrogenic acute type B AD salvaged by renal and iliac stent insertion. Unlike type A AD which requires surgical therapy, the treatment of acute type B AD is determined by the presence of complications, including malperfusion, acute renal failure, or aortic rupture[10]. Complicated type B AD requires thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) or open surgery when symptoms or signs persist despite medical treatment[10]. Although TEVAR has produced favorable results in type B AD, open surgery may be primarily considered, in subjects with connective tissue disease and large aortic diameter (> 45 mm)[10]. As seen in the current case, percutaneous angioplasty was performed due to the compromised flow to the right limb and kidney.

When ARSA is suspected during right TRI, a careful approach is needed to avoid iatrogenic AD. Transluminal angioplasty can be considered a treatment option for complicated type B AD caused by such circumstances.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chang A, Thailand; El-Serafy AS, Egypt S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Mahmodlou R, Sepehrvand N, Hatami S. Aberrant Right Subclavian Artery: A Life-threatening Anomaly that should be considered during Esophagectomy. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2014;6:61-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hanneman K, Newman B, Chan F. Congenital Variants and Anomalies of the Aortic Arch. Radiographics. 2017;37:32-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Scala C, Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Candiani M, Venturini PL, Ferrero S, Greco T, Cavoretto P. Aberrant right subclavian artery in fetuses with Down syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46:266-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | de Araújo G, Junqueira Bizzi JW, Muller J, Cavazzola LT. "Dysphagia lusoria" - Right subclavian retroesophageal artery causing intermitent esophageal compression and eventual dysphagia - A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;10:32-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Polguj M, Chrzanowski Ł, Kasprzak JD, Stefańczyk L, Topol M, Majos A. The aberrant right subclavian artery (arteria lusoria): the morphological and clinical aspects of one of the most important variations--a systematic study of 141 reports. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:292734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li QL, Zhang XM. Aortic dissection originating from an aberrant right subclavian artery. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:1270-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yiu KH, Chan WS, Jim MH, Chow WH. Arteria lusoria diagnosed by transradial coronary catheterization. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:880-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huang IL, Hwang HR, Li SC, Chen CK, Liu CP, Wu MT. Dissection of arteria lusoria by transradial coronary catheterization: a rare complication evaluated by multidetector CT. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:379-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guzman ED, Eagleton MJ. Aortic dissection in the presence of an aberrant right subclavian artery. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26:860.e13-860.e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Munshi B, Ritter JC, Doyle BJ, Norman PE. Management of acute type B aortic dissection. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:2425-2433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |