Published online Sep 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i26.9417

Peer-review started: April 25, 2022

First decision: June 8, 2022

Revised: June 20, 2022

Accepted: August 5, 2022

Article in press: August 5, 2022

Published online: September 16, 2022

Processing time: 129 Days and 15 Hours

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), an aggressive and rare disease that belongs to a heterogeneous group of mature T-cell lymphomas, develops rapidly and has a poor prognosis. Early detection and treatment are essential to improve patient cure and survival rates. Here, we report a rare case of PTCL with clinical presentation of noncirrhotic portal hypertension, which provides a basis for early vigilance of lymphomas in the future.

A 65-year-old Chinese woman was admitted to our hospital because of abdominal distension for 3 months and pitting oedema of both lower limbs for 2 months. Physical examinations and associated auxiliary examinations showed the presence of hepatosplenomegaly, and her hepatic venous pressure gradient was 10 mmHg. Immunohistochemical analysis of the liver biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of PTCL. The patient underwent combination therapy with dexame

PCTL accompanied by noncirrhotic portal hypertension is rarely reported. This case report discusses the diagnosis of a patient according to the literature.

Core Tip: Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) is an aggressive and rare disease that belongs to a heterogeneous group of mature T-cell lymphomas, and is classified as PTCL, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS). It is the most common type and most often involves nodal sites; however, many patients present with extranodal involvement, including the liver, bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, and skin. The clinical presentations of PTCL are lymphadenopathy syndrome and B symptoms (night sweats, fever, and weight loss). Noncirrhotic portal hypertension, hydrothorax and ascites can also occur in rare cases, and noncirrhotic portal hypertension and ascites are less common as first symptoms. Here, we report a rare case of a patient with PTCL who presented with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

- Citation: Wu MM, Fu WJ, Wu J, Zhu LL, Niu T, Yang R, Yao J, Lu Q, Liao XY. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension due to peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(26): 9417-9427

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i26/9417.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i26.9417

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) is an aggressive and rare disease that belongs to a heterogeneous group of mature T-cell lymphomas, and is classified as PTCL not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS). It is the most common type and most often involves nodal sites; however, many patients present with extranodal involvement, including the liver, bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, and skin[1]. The clinical presentations of PTCL are lymphadenopathy syndrome and B symptoms (night sweats, fever, and weight loss). Noncirrhotic portal hypertension, hydrothorax, and ascites can also occur in rare cases[2,3], and noncirrhotic portal hypertension and ascites are less common as first symptoms. Here, we report a rare case of a patient with PTCL who presented with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

A 65-year-old Chinese woman was referred to our hospital due to abdominal distension for over 3 months and pitting oedema of both lower limbs for over 2 mo.

Approximately 3 mo previously, this patient was admitted to a local hospital due to abdominal distension. Additional symptoms included pitting oedema of both lower limbs, anorexia and melena, and the patient lost 5 kg in two months. The patient had no jaundice, fever, or night sweats. Ultrasonography (US) indicated that she had neither oesophageal nor gastric varices or ulcers. but gastroscopic examination showed external compression of large gastric curvature, the cause of gastric wall compression is unknown, taking into account the left side of lying stomach bend side close to the spleen. Extra-hospital computed tomography (CT) showed hepatosplenomegaly and no other lesions around the stomach. So we think the growth of the spleen is the most likely reason for the external pressure of the greater curvature of the stomach. After 10 days of albumin infusion therapy, the above symptoms were not relieved but rather further aggravated. Therefore, she was referred to a tertiary hospital.

She had no history of hepatitis and no significant past medical history.

The physical examination revealed that the patient had abdominal varices and an increase in abdominal circumference to 98 cm.

Laboratory tests showed that her white blood cell count was 1.80 × 109/L (reference value 3.5-9.5 × 109/L), the neutrophil count was 1.33 × 109/L (reference value 1.8-6.3 × 109/L), the neutrophil percentage was 73.80% (reference value 40%-75%), haemoglobin was 71 g/L (reference value 115-150 g/L), platelet count was 54 × 109/L (reference value 100-300 × 109/L), albumin was 26.5 g/L (reference value 40.0-55.0 g/L), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 347 IU/L (reference value 120-250 IU/L), and liver and renal function were within normal limits. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 3.0 mm/h (reference value < 38 mm/h). Coagulation function revealed a prothrombin time of 18.2 s (reference value 9.6-12.8 s), and fibrinogen was 0.64 g/L (reference value 2.0-4.0 g/L) (Table 1). Tests for Epstein-Barr virus, tuberculosis, and hepatitis B, A, C, D, and E were all negative.

| Laboratory tests | Result | Reference value |

| White blood cell count | 1.80 × 109/L | 3.5-9.5 × 109/L |

| Neutrophil count | 1.33 × 109/L | 1.8-6.3 × 109/L |

| Neutrophil percentage | 0.738 | 40-75% |

| Haemoglobin | 71 g/L | 115-150 g/L |

| Platelet count | 54 × 109/L | 100-300 × 109/L |

| Albumin | 26.5 g/L | 40.0-55.0 g/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 347 IU/L | 120-250 IU/L |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 3.0 mm/h | < 38 mm/h |

| Coagulation function revealed a prothrombin time of | 18.2 s | 9.6-12.8 s |

| Fibrinogen | 0.64 g/L | 2.0-4.0 g/L |

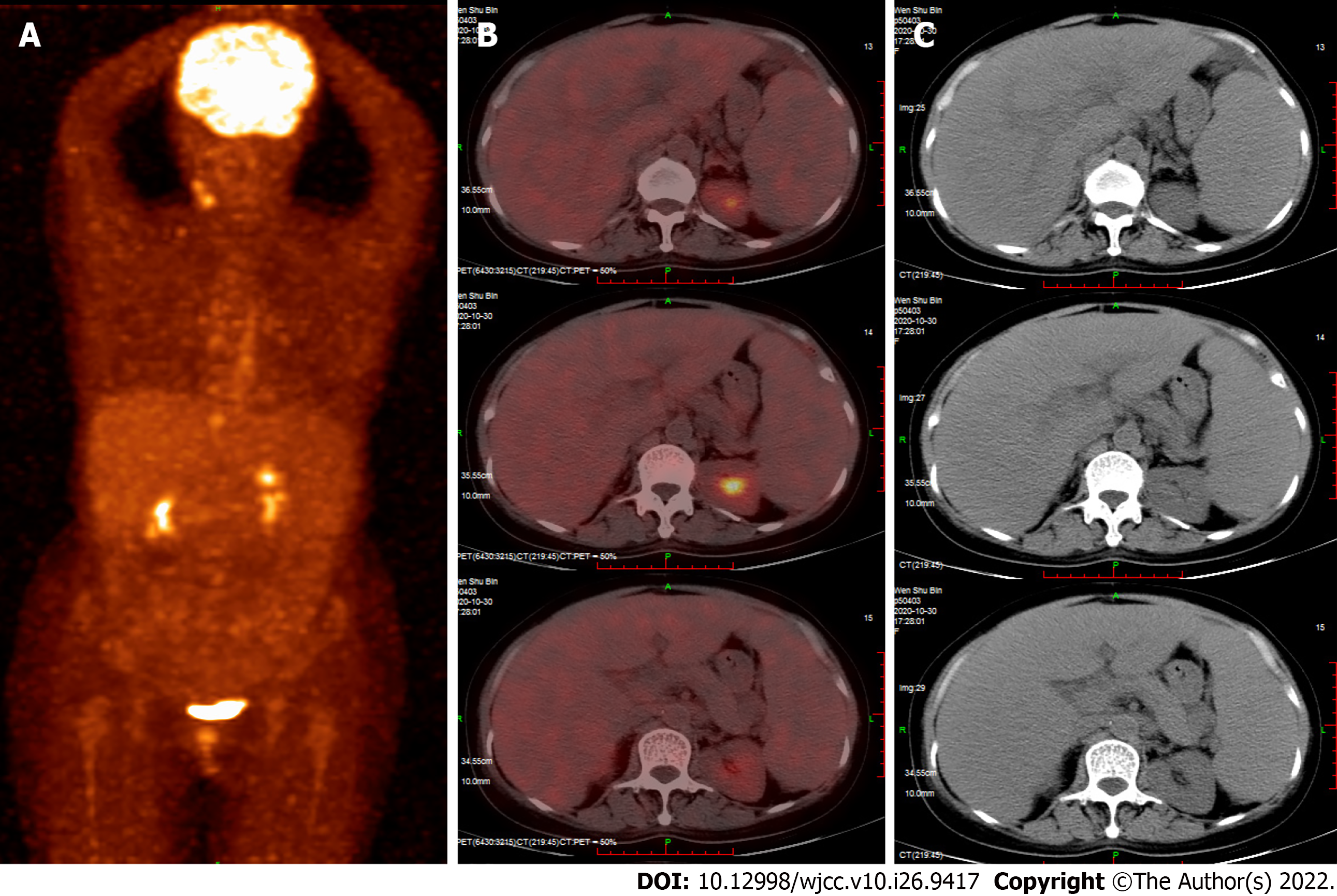

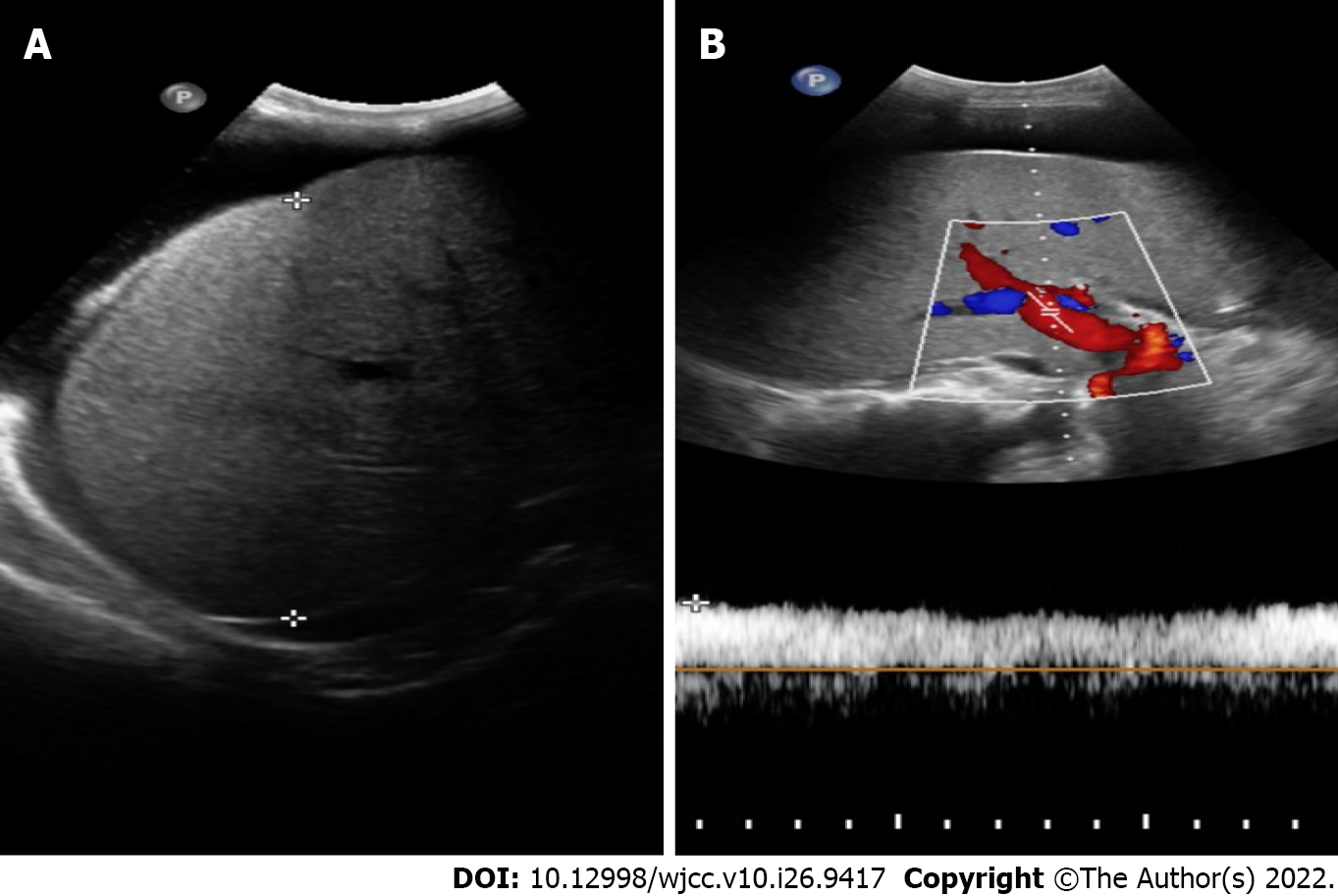

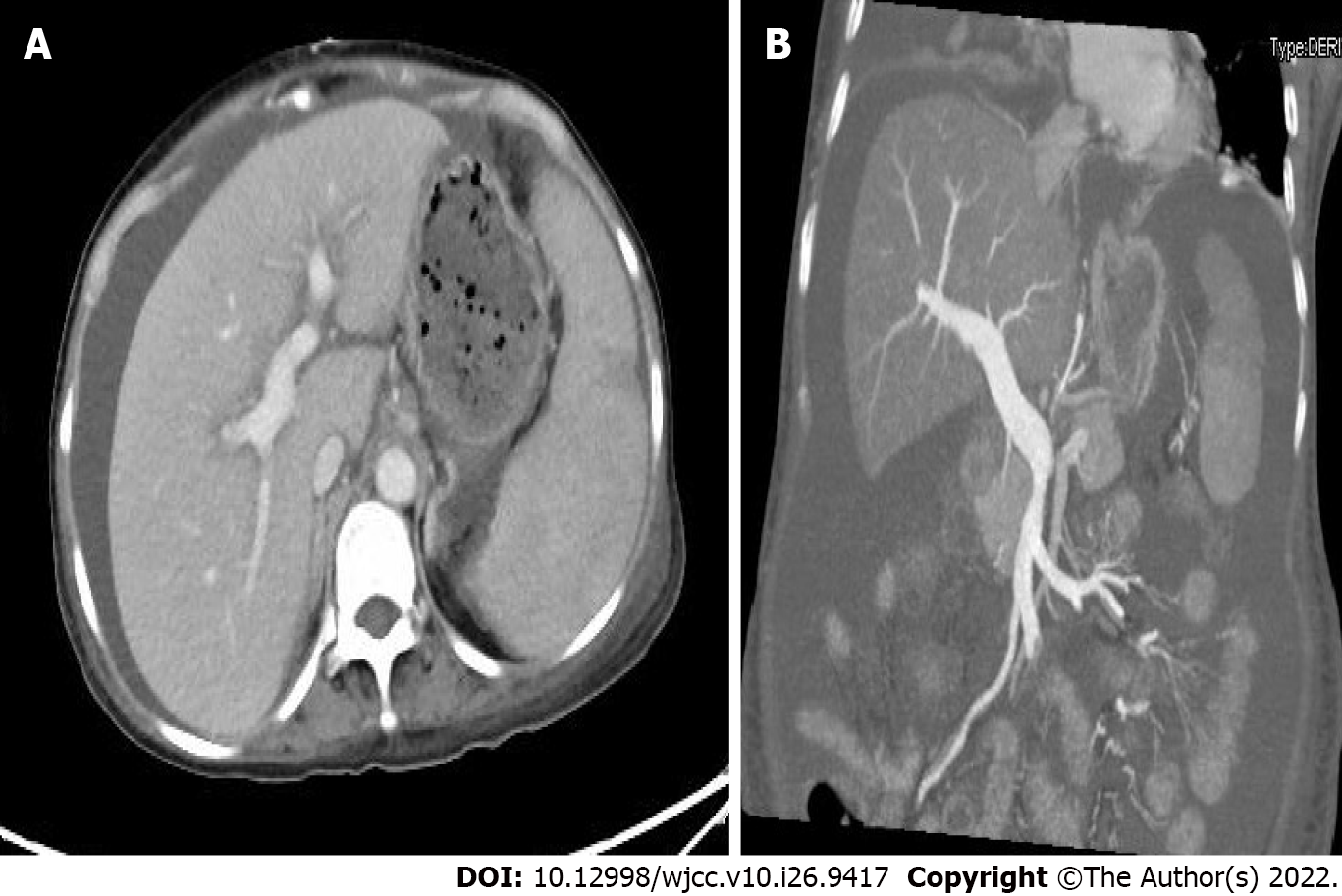

Positron emission tomography-CT (PET) indicated hepatosplenomegaly and swelling of the peritoneum, mesentery, descending duodenum, and horizontal segments (Figure 1). Liver ultrasound showed increased liver volume; no cirrhosis-specific nodular changes were observed, and liver stiffness was measured at 19.55 kPa (Figure 2). CT also showed an enlarged liver volume, parenchymal density, and acceptable strengthening, as well as a small, tiny cyst. Two sides of the intrahepatic portal vein showed no enhancement of the low-density strip, showing a "double-track sign". Consideration was given to the possibility of intrahepatic lymphatic stasis. Liver computed tomographic arteriography showed hepatosplenomegaly without portal vein, splenic vein, or mesenteric arteriovenous thrombosis (Figure 3).

Relevant laboratory data for ascites were as follows: appearance was yellow and cloudy, nucleated cells were 40 × 106/L, red blood cells were 6700 × 106/L, albumin was 25.3 g/L, glucose was 6.85 mmol/L, LDH was 246 IU/L, serum-ascites LDH gradient was 0.87, adenosine deaminase was 27.8 IU/L, the serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) was 1.3, the ascitic fluid bacterial culture showed no bacterial growth, and the tuberculosis antibody test was negative. The hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) measured by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) was 10 mmHg.

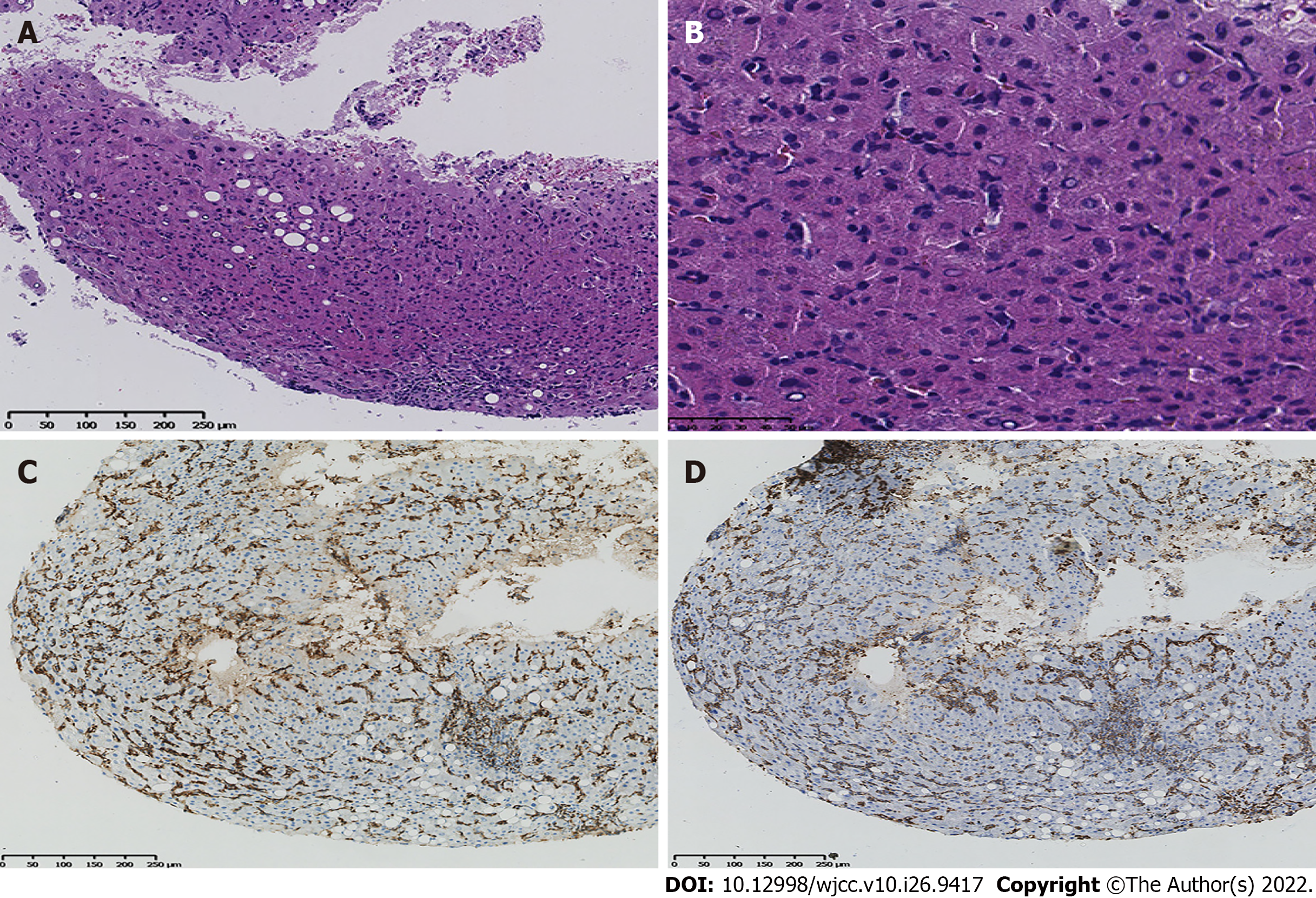

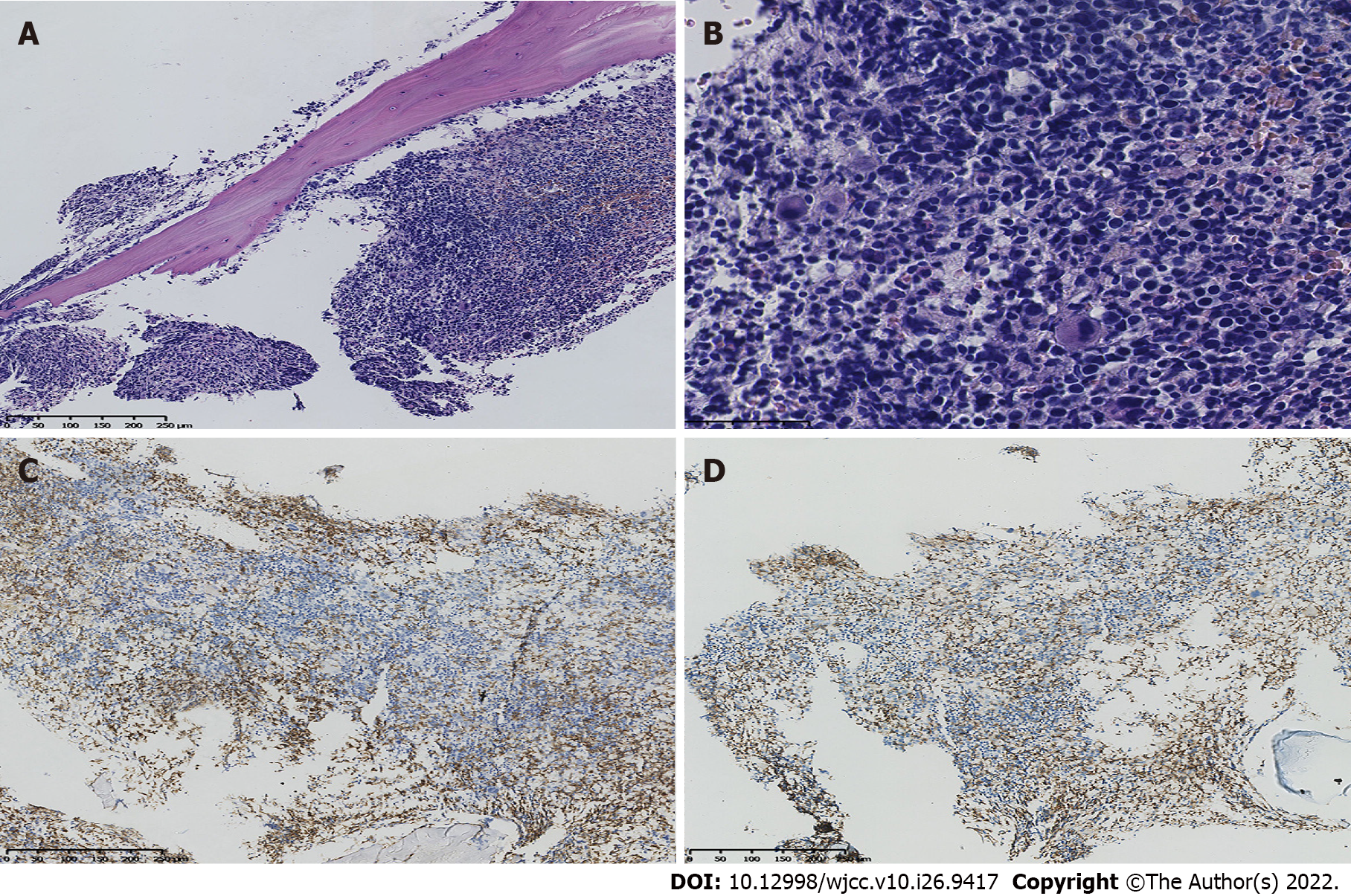

Ascites immunocytology showed that the lymphocyte population composition was approximately 93.3% nucleated cells, of which approximately 14.5% were weakly positive for CD5. Immunohistochemistry staining showed that the lymphocytes were positive for CD2, CD3, CD7, CD8, CD56, CD57, and T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ but negative for CD11c, CD16, CD4, and TCR γδ. Because of the limitation of the medical technique used, DNA ploidy analysis of the exfoliated cells of the benign and malignant hydrothorax as well as flow cytometry of the ascites were not performed. Immunohistochemical analysis, performed on a bone marrow biopsy and aspiration (Figure 4), showed that cells were positive for CD3, CD7, and CD56 and negative for CD20, CD2, CD5, CD4, CD8, TIA-1, CD30, and CD34, as well as for Epstein–Barr virus-encoded RNAs, using in situ hybridization. Medical examination of ascites and bone marrow revealed a T-cell lymphoma. HVPG was measured by TIPS, liver biopsy was performed, and immunohistochemistry was performed. Macroscopically, 4 strips of grey yellow cord-like tissue, approximately 0.8-1.3 cm in length and 0.1 cm in diameter, were positive for CD3, CD5, CD7, CD8, CD43, CD56, TIA-1, and Ki-67 and negative for CD2, CD20, CD4, CD30, CD34, and TdT (Figure 5). Gene rearrangements are seen in the TCR γ low amplification peak (Table 2).

| Parameter | Marrow | Ascites | Hydrothorax | Liver |

| CD2 | ++ | + | + | - |

| CD3 | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| CD4 | - | - | - | - |

| CD5 | + | + | + | |

| CD7 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| CD8 | + | + | ++ | + |

| CD11c | - | - | ||

| CD16 | - | + | - | |

| CD30 | - | |||

| CD34 | - | |||

| CD38 | - | ++ | ||

| CD43 | + | |||

| CD45 | + | |||

| CD56 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| CD57 | + | +p | ++ | |

| TCRαβ | + | + | ||

| TCRγδ | - | - | ||

| TIA-1 | - | |||

| TDT | - | |||

| Ki-67 | + |

Eventually, after twenty days, the patient was diagnosed with an aggressive T-cell lymphoma (stage IV), which was categorised as a PTCL-NOS.

The patient was diagnosed with T-cell lymphoma and was given 5 mg dexamethasone once a day. After four days of hormone therapy, the patient's oedema of both lower extremities was alleviated, but the reduction was not obvious; therefore, 25 mg etoposide once a week was added. After two days, the oedema of both lower limbs was significantly improved; however, ascitic changes were unremarkable. After 12 days, the patient was put on chidamide chemotherapy at the recommended starting dose of 20 mg, 1 to 3 times per week, 20 to 50 mg each time; the patient took the medication for 22 days with a cumulative dose of 110 mg, and the oedema of both lower limbs disappeared completely; however, ascites remained unchanged.

The patient’s international prognostic index was 5, which meant that she was in the high-risk group with a low 5-year survival rate[4]. Chidamide has a slower onset of action, and over the course of her treatment, her ascites did not improve. Unfortunately, after 41 d of chemotherapy, the patient died of multiple organ failure.

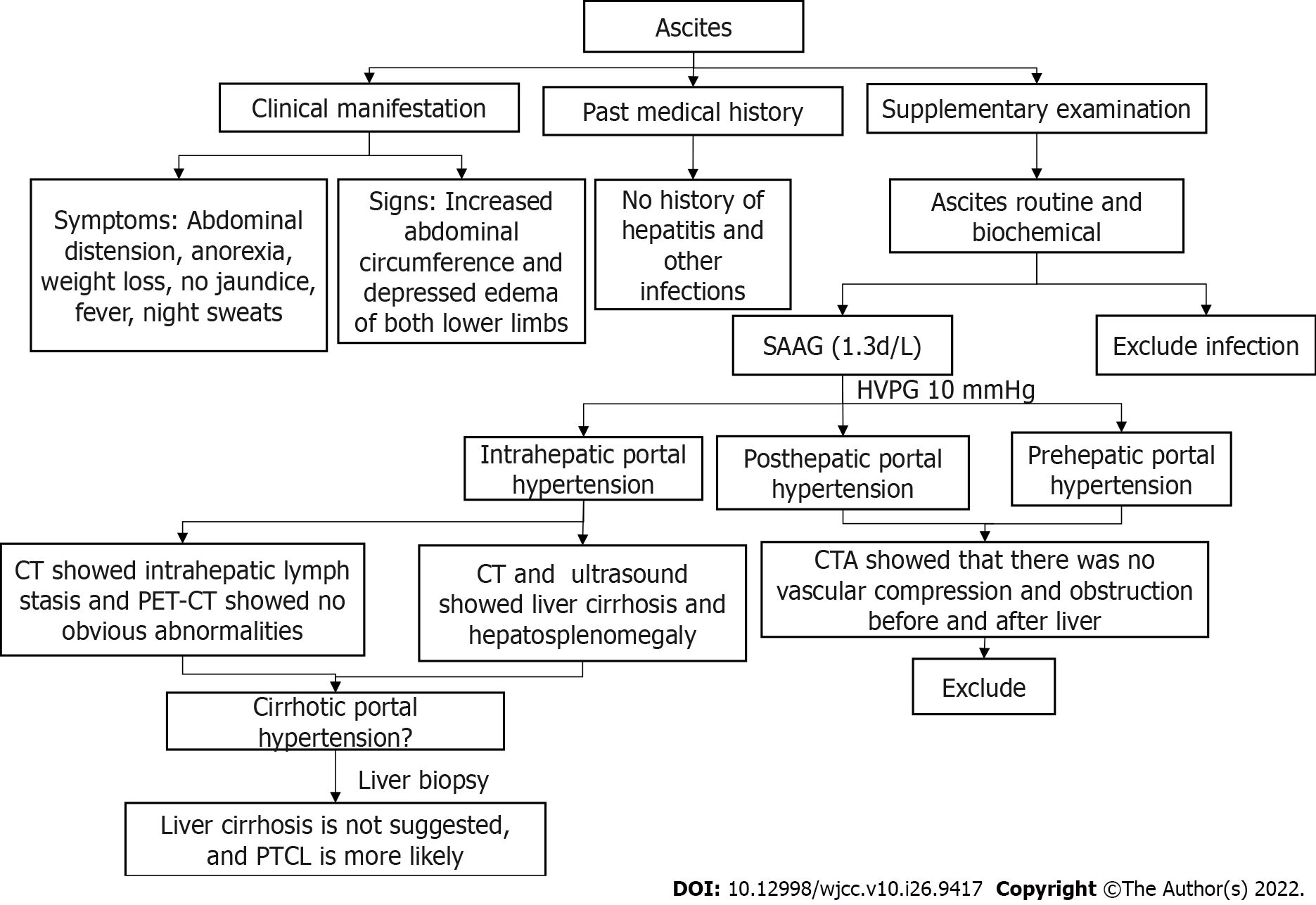

PTCL is an aggressive and rare disease that belongs to a heterogeneous group of mature T-cell lymphomas that constitute less than 15% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas in adults[5,6]. The most common symptoms included lymphadenopathy and B symptoms (night sweats, fever, and weight loss). The initial findings in the patient were portal hypertension, ascites, splenomegaly, and routine biochemistry of ascites showing no infection. SAAG was 1.3, and HVPG was 10 mmHg. Ultrasound and CT showed hepatosplenomegaly and liver cirrhosis. CTA showed that there was no obstruction or compression of blood vessels before and after the trunk. Therefore, we excluded prehepatic and posthepatic portal hypertension and focused on intrahepatic portal hypertension[7], and the patient’s intrahepatic lymphatic stasis confirmed this speculation[8]. Although all examinations of our patients showed cirrhosis, the patient’s liver was enlarged, so we had to doubt the accuracy of the examination. To our knowledge, the gold standard for cirrhosis is liver biopsy, which can be performed for diagnostic purposes when the diagnosis is uncertain. Before they are properly diagnosed, most patients are misdiagnosed as having hepatic cirrhosis, potentially delaying treatment. Consequently, the patient was subjected to a liver biopsy which confirmed the absence of cirrhosis; thus, this presentation was either PTCL or NOS (Figure 6).

Portal hypertension is a rare manifestation in lymphomas. By searching cases of PTCL-related portal hypertension and ascites (Table 3), we found that only one report[9] described a T-cell lymphoma patient presenting with portal hypertension and oesophageal and gastric varices but no ascites and whose diagnosis was confirmed by splenectomy. Four cases[10-13] mentioned ascites, but none reported whether there was portal hypertension and only reported diagnosis by ascites flow cytometry. The mechanism of portal hypertension is not mentioned in the above cases. We speculate that the reason for the noncirrhotic portal hypertension in this patient was intrahepatic portal hypertension caused by the obstruction of a portal venous return due to intrahepatic lymph stasis. At the same time, visceral hyperdynamic circulation is one of the causes of increased portal blood flow and thus increased portal venous system pressure[14-16]. This case may be due to increased liver blood flow caused by tumours resulting in visceral hyperdynamic circulation leading to liver enlargement and portal hypertension. These two mechanisms together led to the development of noncirrhotic portal hypertension in this patient.

| Ref. | Age, Gender | Course of disease | Clinical Symptoms | Supplementary Examination | Biopsy Source | Immunohistochemistry | Diagnosis | Invasion of other parts | Treatment | Prognosis |

| Ameri[13] | 61, F | 2+W | Abdominal discomfort | Ascites, hepatosplenomegaly | Ascites | CD4(+), CD2(+), CD5(+), CD3(+), CD7(-), CD16(-), CD56(-), CD57(-), TdT(-) | PTCL, NOS | Bone marrow | No treatment | NA |

| Yamamoto[10] | 72, W | 3+W | Abdominal discomfort | Hydrothorax and ascites | Ascites | CD2 (+), CD3(+) (+),CD45(+), CD4 (–), CD8 (–) | PTCL | Thorax and abdomen | Cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, vincristine, etoposide, bleomycin, and prednisolone | Died of multiple organ failure |

| Izban[12] | 76, F | Abdominal tenderness | Ascites, splenomegaly | Ascites | CD2(+), CD3(+), CD5(+), CD7(+), CD45(+), CD4(-), CD8(-) | PTCL | Bone marrow, liver | CHOP chemotherapy | Recurrence after chemotherapy | |

| VakarLópez[11] | 49, W | 3+M | Abdominal tenderness | Ascites | Ascites | CD3(+) | PTCL, NOS | No treatment | NA | |

| Lindor[9] | 65, F | 2+Y | Pectoralgia, esophageal and gastric variceal bleeding (EGVB) | Splenomegaly, EGVB | spleen | NA | Diffuse mixed-type T-cell lymphoma | Splenectomy | Bone marrow infiltration occurred 1 + year after the operation | |

In the relevant literature, most patients are diagnosed based on ascites flow patterns, but in this case, due to insufficient sampling, the ascites flow pattern could not be successfully made. TIPS was used to perform portal pressure measurement and liver biopsy in this patient, and the diagnosis was finally made based on the biopsy results. TIPS is an interventional radiotherapy technique developed in the past 20 years. It uses the internal jugular vein as the puncture entrance, inserts the catheter through the superior vena cava, right atrium, and inferior vena cava, and inserts the hepatic vein into the hepatic vein under the guidance of an X-ray. Establishing an artificial shunt channel between them can not only measure the portal venous pressure to achieve the purpose of diagnosis but also reduce portal hypertension and achieve the purpose of treatment[17-19]. TIPS has been widely used for the diagnosis and treatment of portal hypertension[20]. TIPS is considered to be a successful and efficacious procedure with a 90% success rate[21,22]. Although there are unavoidable risks, recent studies have shown a high efficacy of TIPS compared to other treatments and presented an acceptable complication rate[23,24]. Research has shown that TIPS placement can be used for noncirrhotic portal hypertension[25]. At the same time, TIPS can also be used for liver biopsy to obtain a pathological diagnosis. When the patient was diagnosed with portal hypertension by TIPS, a liver biopsy was also performed, which was the key to the final diagnosis of the patient.

Therefore, when noncirrhotic portal hypertension is the main manifestation, all examinations suggest liver cirrhosis, but imaging does not conform to the characteristics of liver cirrhosis, such as liver enlargement. TIPS examination can be considered, which can not only measure portal pressure but also perform a biopsy to achieve the purpose of diagnosis, and the examination risk is relatively low. This study is helpful to reduce the missed diagnosis rate of lymphoma. PTCL-NOS has a poor prognosis, and the commonly used CHOP regimen is not effective[26-29]. Chidamide also takes at least 4 weeks to take effect. Early diagnosis can lead to more treatment opportunities and increase the prognosis of patients.

In conclusion, we describe a PTCL case presenting with ascites and noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Cases of noncirrhotic portal hypertension in PTCL are rare. When the clinical signs and auxiliary examinations suggest liver cirrhosis, as long as there is noncompliance with liver cirrhosis (hepatosplenomegaly), we should be alert to the possibility of other causes, such as lymphoma, reducing missed diagnosis of lymphoma.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, general and internal

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cheng J; Salimi M, Iran S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Oluwasanjo A, Kartan S, Johnson W, Alpdogan O, Gru A, Mishra A, Haverkos BM, Gong J, Porcu P. Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma, not Otherwise Specified (PTCL-NOS). Cancer Treat Res. 2019;176:83-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Das DK. Serous effusions in malignant lymphomas: a review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:335-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Attanoos R. Lymphoproliferative conditions of the serosa. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:268-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sonnen R, Schmidt WP, Müller-Hermelink HK, Schmitz N. The International Prognostic Index determines the outcome of patients with nodal mature T-cell lymphomas. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:366-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vega F. Pathology and Pathogenesis of T-Cell Lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20 Suppl 1:S89-S93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vega F, Amador C, Chadburn A, Feldman AL, Hsi ED, Wang W, Medeiros LJ. American Registry of Pathology Expert Opinions: Recommendations for the diagnostic workup of mature T cell neoplasms. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2020;49:151623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Carrier P, Jacques J, Debette-Gratien M, Legros R, Sarabi M, Vidal E, Sautereau D, Bezanahary H, Ly KH, Loustaud-Ratti V. [Non-cirrhotic ascites: pathophysiology, diagnosis and etiology]. Rev Med Interne. 2014;35:365-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rajesh S, Mukund A, Sureka B, Bansal K, Ronot M, Arora A. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: an imaging review. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:1991-2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lindor K, Rakela J, Perrault J, Van Heerden J. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension due to lymphoma. Reversal following splenectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:1056-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yamamoto Y, Kitajima H, Sakihana H, Shigeki T, Fukuhara S. CD3+CD4-CD8-TCR-alphabeta+ T-cell lymphoma with clinical features of primary effusion lymphoma: an autopsy case. Int J Hematol. 2001;74:442-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vakar-López F, Yang M. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma presenting as ascites: a case report and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20:382-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Izban KF, Pooley RJ Jr, Selvaggi SM, Alkan S. Cytologic diagnosis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma manifesting as ascites. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:385-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ameri MD, Parekh TM, Qian YW, Elghetany MT, Schnadig V, Nawgiri R. A case of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified in a HCV and HTLV-II-positive patient, diagnosed by abdominal fluid cytology. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:S96-S99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vuppalanchi R, Mathur K, Pyko M, Samala N, Chalasani N. Liver Stiffness Measurements in Patients with Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension-The Devil Is in the Details. Hepatology. 2018;68:2438-2440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Khanna R, Sarin SK. Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension: Current and Emerging Perspectives. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23:781-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Da BL, Koh C, Heller T. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018;34:140-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bucsics T, Lampichler K, Vierziger C, Schoder M, Wolf F, Bauer D, Simbrunner B, Hartl L, Jachs M, Scheiner B, Trauner M, Gruenberger T, Karnel F, Mandorfer M, Reiberger T. Covered Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Improves Hypersplenism-Associated Cytopenia in Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Artru F, Moschouri E, Denys A. Direct intrahepatic portocaval shunt (DIPS) or transjugular transcaval intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TTIPS) to treat complications of portal hypertension: Indications, technique, and outcomes beyond Budd-Chiari syndrome. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2022;46:101858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Madhusudhan KS, Sharma S, Srivastava DN. Percutaneous radiological interventions of the portal vein: a comprehensive review. Acta Radiol. 2022;2841851221080554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang C, Liu J, Yao J, Ju S, Wang Y, Yang C, Bai Y, Yao W, Li T, Chen Y, Huang S, Xiong B. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with autoimmune hepatitis-induced cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022;47:1464-1472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tandon B, Ramachandran J, Narayana S, Muller K, Pathi R, Wigg AJ. Outcomes of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedures: a 10-year experience. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2021;65:655-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Grewal S, Sidhu R, Elhassan M. Rings Flying Around: A rare complication of Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt. Respir Med Case Rep. 2022;36:101586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee HL, Lee SW. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with portal hypertension: Advantages and pitfalls. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28:121-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Qiu Z, Zhu W, Yan H, Wang G, Zuo M, Qi H, Jiang W, Xue J, Zhang F, Gao F. Single-Centre Retrospective Study Using Propensity Score Matching Comparing Left Versus Right Internal Jugular Vein Access for Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) Creation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022;45:563-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shreve LA, O'Leary C, Clark TWI, Stavropoulos SW, Soulen MC. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for the management of symptomatic malignant pseudocirrhosis. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;13:279-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu W, Ji X, Song Y, Wang X, Zheng W, Lin N, Tu M, Xie Y, Ping L, Ying Z, Zhang C, Deng L, Wu M, Feng F, Leng X, Sun Y, Du T, Zhu J. Improving survival of 3760 patients with lymphoma: Experience of an academic center over two decades. Cancer Med. 2020;9:3765-3774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Iżykowska K, Rassek K, Korsak D, Przybylski GK. Novel targeted therapies of T cell lymphomas. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Foster C, Kuruvilla J. Treatment approaches in relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphomas. F1000Res. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Allen PB, Pro B. Therapy of Peripheral T Cell Lymphoma: Focus on Nodal Subtypes. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |