Published online Sep 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i26.9368

Peer-review started: April 13, 2022

First decision: May 12, 2022

Revised: May 24, 2022

Accepted: August 5, 2022

Article in press: August 5, 2022

Published online: September 16, 2022

Processing time: 141 Days and 18.1 Hours

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute self-limiting febrile vasculitis that occurs during childhood and can cause coronary artery aneurysm (CAA). CAAs are associated with a high rate of adverse cardiovascular events.

A Korean 35-year-old man with a 30-year history of KD presented to the emergency room with chest pain. Emergent coronary angiography was performed as ST-segment elevation in the inferior leads was observed on the electrocardiogram. An aneurysm of the left circumflex (LCX) coronary artery was found with massive thrombi within. A drug-eluting 4.5 mm 23 mm-sized stent was inserted into the occluded area without complications. The maximal diameter of the LCX was 6.0 mm with a Z score of 4.7, suggestive of a small aneurysm considering his age, sex, and body surface area. We further present a case series of 19 patients with KD, including the current patient, presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Notably, none of the cases showed Z scores; only five patients (26%) had been regularly followed up by a physician, and only one patient (5.3%) was being treated with antithrombotic therapy before ACS occurred.

For KD presenting with ACS, regular follow up and medical therapy may be crucial for improved outcomes.

Core Tip: Kawasaki disease can lead to coronary artery aneurysms. The presence of a coronary artery aneurysm increases the risk of developing acute coronary syndrome. However, we found that proper long-term medical care or regular examination had not been provided to the 19 previously reported patients in this case series. Thus, based on the Z scores, our data highlight the importance of meticulous care by a cardiac specialist.

- Citation: Lee J, Seo J, Shin YH, Jang AY, Suh SY. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in Kawasaki disease: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(26): 9368-9377

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i26/9368.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i26.9368

Kawasaki disease (KD) is one of the most common causes of acute self-limited febrile illnesses resulting in vasculitis during childhood[1]. The incidence of KD is the highest in boys under 5 years of age and in East Asia[2,3]. In an Asian nationwide cohort, the annual risk of coronary complications was 2.4% during 2000-2010, and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction (MI) was 1.52%[4]. KD can cause multiple complications throughout the body[5]. Cardiac complications, such as coronary artery aneurysm, heart failure, MI, and arrhythmia, lead to significant morbidity and mortality[6]. KD-related vasculitis destroys medium-sized arteries, among which coronary arteries are commonly influenced. Coronary arteries affected by KD have been reported to develop coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) in up to 25% of untreated patients[6-9], whereas the incidence drops to approximately 4% when treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)[10,11]. Such aneurysms are also known to be associated with coronary artery diseases[12]. Moreover, as the size of the aneurysm increases, the prevalence of MI also increases[6]. At four United States hospitals in San Diego, 5% of patients under 40 years of age with suspected MI who underwent coronary angiography had a history of KD[11]. Herein, we present a case of a male Korean patient with a history of KD presenting with MI; we also discuss a case series of 19 patients with KD who were subsequently diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

A 35-year-old man visited the emergency room (ER) complaining of chest pain.

His symptoms were intermittent once a day before. His chest pain (numeric rating scale of 7) worsened 2 h before visiting the ER.

He had no significant medical history except for the diagnosis of KD at 2 years of age.

He was currently not under any medications. His coronary risk factor was a 5-year smoking history. The patient had quit smoking at the time of visiting the emergency room.

His physical examination was normal, with a blood pressure of 121/72 mmHg, pulse rate of 72 beats per minute, body temperature of 36.8 °C, and a respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute.

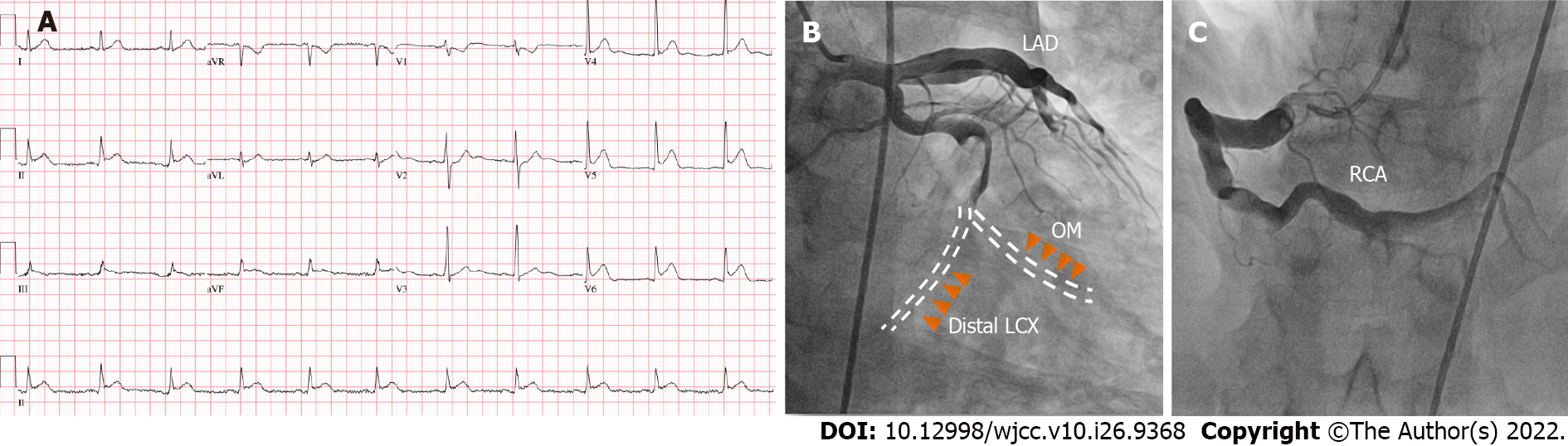

The electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated a sinus rhythm with ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF, and V4-V6 (Figure 1A). Initial blood tests reported that creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB), troponin-I, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol values were 4.970 ng/mL, 236.95 pg/mL, 42 mg/dL, and 204 mg/dL, respectively.

The initial echocardiogram revealed akinesia of the posterolateral wall from the base to the mid-left ventricle and hypokinesia of the anterolateral wall from the base to the mid-left ventricle without thinning, leading to moderately reduced left ventricular systolic function [left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): 47%]. Emergent coronary angiography (CAG) showed aneurysmal dilatation of the proximal segment of the right coronary artery (RCA) and total occlusion of the distal left circumflex (LCX) and obtuse marginal (OM) arteries with sluggish flow (Figure 1A and B).

The final diagnosis of the presented case was ST elevation myocardial infarction due to CAA after KD.

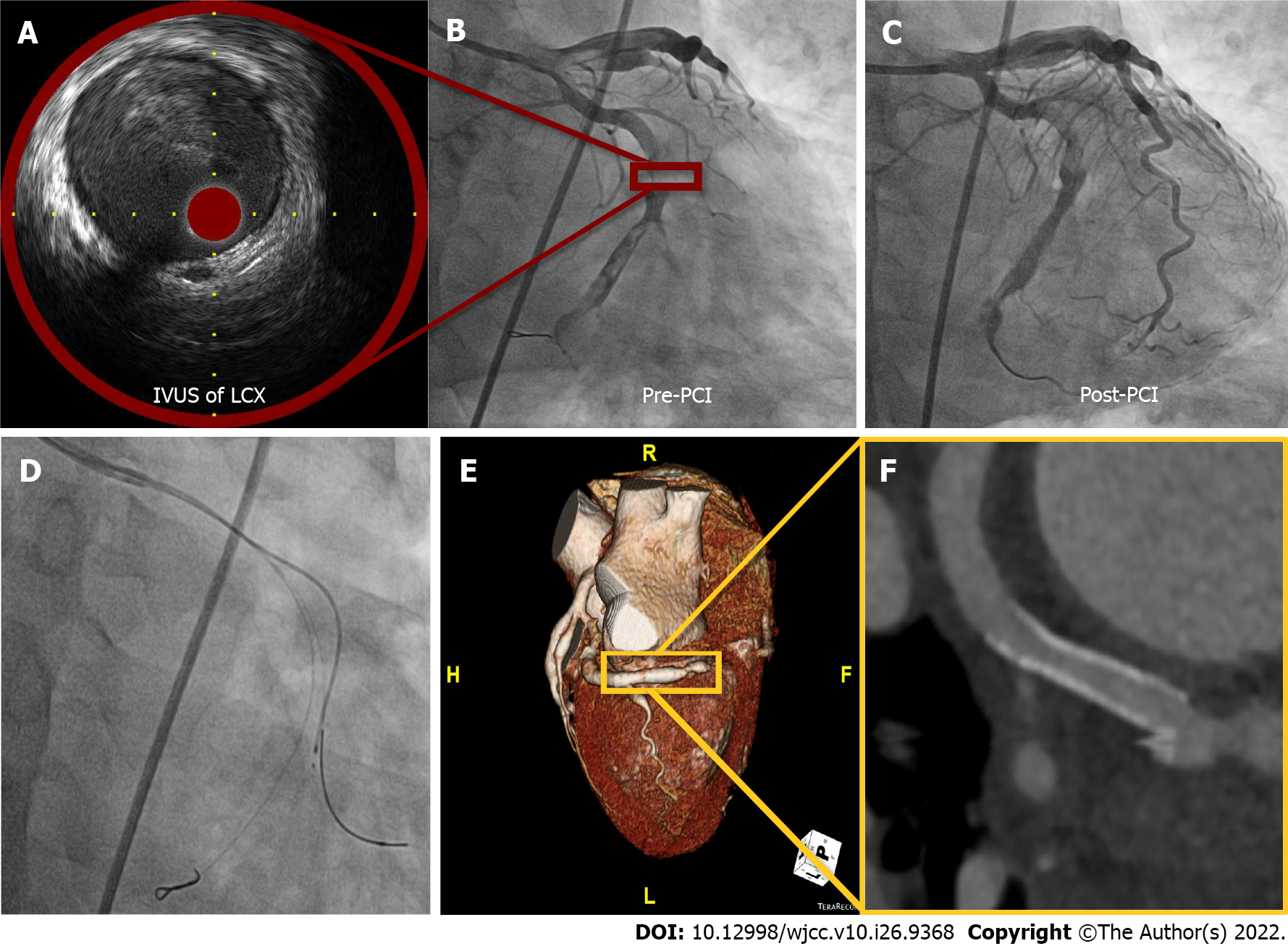

Thrombosuction was performed on the LCX lesion, although the coronary blood flow was not improved. Further, subsequent extensive balloon angioplasty using a 2.5 mm 15 mm balloon to the distal LCX and OM did not restore the blood flow. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS, TVC imaging system™, Infraredx, Inc, Bedford, MA) showed a diameter of 6.0 mm CAA in the distal LCX with a hazy material, suggestive of thrombosis (Figure 2A). Based on these findings, the patient’s Z score was 4.7 (height 167 cm and body weight 73.5 kg), classified as being within a small aneurysm range[13]. We were not able to further advance the IVUS catheter into the OM owing to resistance and angulation (Figure 2D). However, after IVUS examination, fluoroscopy showed the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 2 flow to the distal LCX with massive thrombi (Figure 2B). A drug-eluting stent (GenossTM 4.5 mm 23 mm, Genoss, Suwon, Korea) was successfully inserted (nominal pressure: 10 atm, inflated up to 10 atm) into the culprit lesion without a no-reflow phenomenon (Figure 2C). We decided to insert a drug-eluting stent instead of a bare metal stent because anticoagulation was not considered unless the presence of a giant aneurysm of a Z score > 10 was determined[14].

After the procedure, dual antiplatelets (100 mg aspirin and 90 mg ticagrelor twice daily) and statins (10 mg rosuvastatin) administration was initiated. Owing to the high thromboburden, the patient was treated with intravenous heparin for 48 h post- percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). ST-segment elevation disappeared in the ECG performed 8 h after the procedure. Cardiac markers were observed to peak at 12 h (CK-MB > 300 ng/mL and troponin-I > 25000 pg/mL) post-PCI. The patient was discharged after 3 d without any additional events and was prescribed dual-antiplatelet therapy, nicorandil, and a statin. He is being followed up regularly in the outpatient department. However, the follow-up echocardiogram 6 mo after the initial PCI showed no interval change in LVEF and regional wall motion abnormality. Coronary computed tomography (CT) performed one year later showed good patency at the LCX stent area and ectatic aneurysm in all coronary arteries (Figure 2D and E). The patient is currently being followed up in the outpatient clinic without any events since 2 years while under dual-antiplatelet therapy.

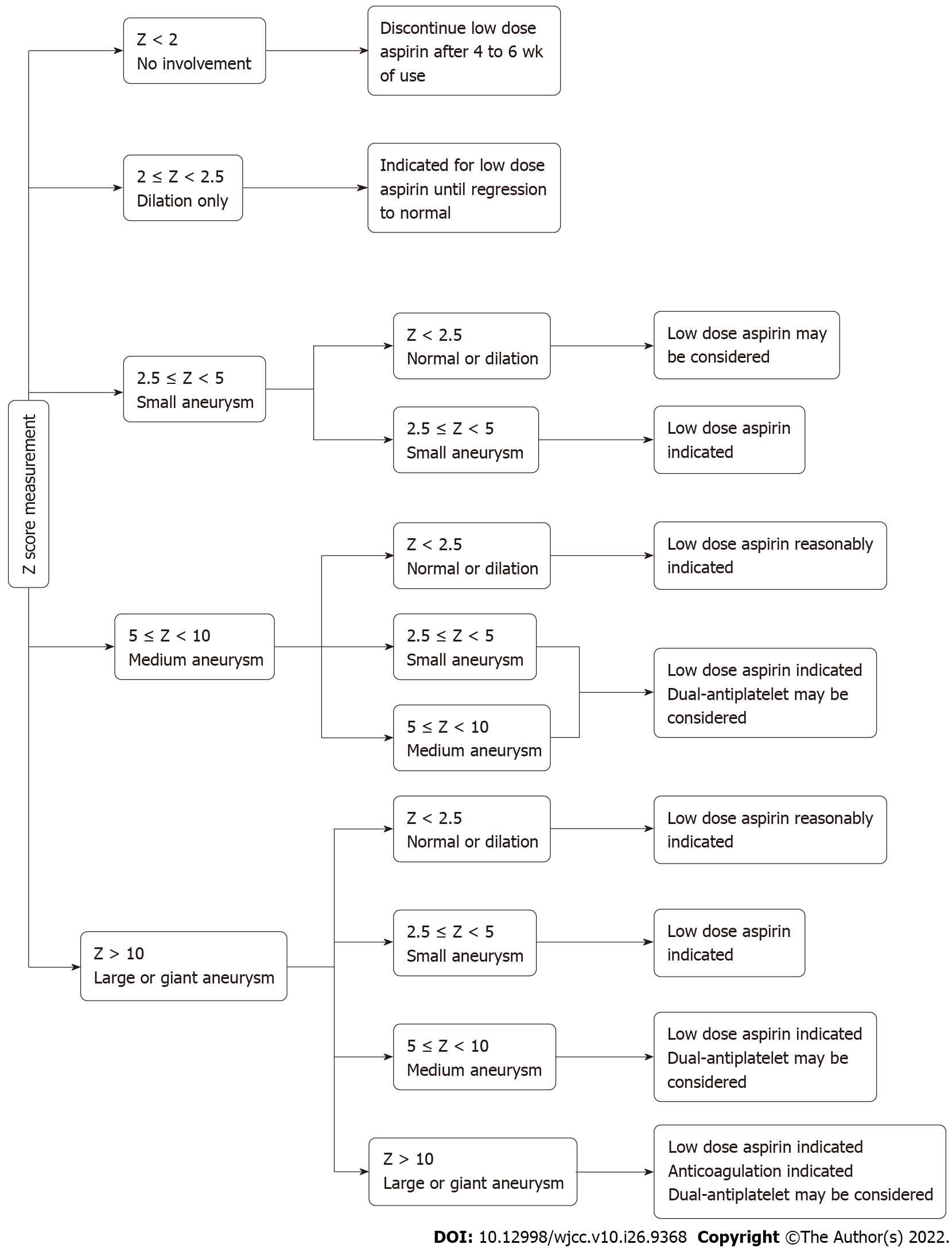

Large CAAs are associated with a high risk of adverse cardiovascular (CV) events[15,16]. Thus, the identification of a potential CAA is crucial for patients diagnosed with KD. Coronary artery abnormalities arising from KD in children can be identified in most cases by echocardiogram[17]. However, visualizing the distal segment of coronary arteries can be challenging. Other imaging modalities can be legitimate options, such as cardiac CT angiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, or CAG. Statistical Z scores have been devised to objectively assess the size of the CAA based on the patient’s age, sex, and body surface area[14]. Thromboprophylaxis is determined by the Z scores according to the recent guidelines[14]. The classification of Z scores of CAA and their corresponding thromboprophylaxis recommendations are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 3[14].

| Agent | Indication | Dose | Monitoring | Mechanism of action |

| Aspirin | Initial therapy for prevention of thrombosis.(Z score ≥ 2.5) | 3-5 mg/kg/day | - | Cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitor |

| Clopidogrel | Resistance to aspirin or aspirin allergy. Dual-antiplatelet therapy for thromboprophylaxis | 0.2-1.0 mg/kg/day | - | P2Y12 inhibitor |

| Prasugrel/ticagrelor | NA | NA | NA | P2Y12 inhibitor |

| Warfarin | Thromboprophylaxis for large or giant aneurysm. (Z score > 10) | INR 2-3 | Vitamin K antagonist | |

| LMWH | Thromboprophylaxis for large or giant aneurysm.(Z score > 10) | Dosage varies according to age and agent | - | Active antithrombin III |

The primary treatments for KD include IVIG and aspirin[18]. A meta-analysis showed that the use of high-dose IVIG reduced the progression to CAA[19]. In patients with IVIG-resistant KD, corticosteroids and infliximab can be used for the prevention of CAA. Once a CAA is formed, the goal is the primary prevention of coronary thrombosis. Although there is no study comparing the outcome in those with or without appropriate follow up and imaging surveillance to date, it is recommended by expert consensus[14]. Further studies are required to demonstrate the usefulness of imaging surveillance. Additionally, despite the limited evidence on the benefit of the use of antiplatelets, it is recommended by expert consensus as well[14]. The benefit of additional anticoagulation in patients with Z score-based giant aneurysms was, however, demonstrated by a previous study[20]. Anticoagulation is recommended in such patients[14]. For small CAAs (2.5 ≤ Z score < 5), low-dose aspirin is recommended[14], whereas a combination of aspirin and warfarin is recommended for those with giant aneurysms (Z score > 10) (Table 1 and Figure 3)[21]. Additionally, it is recommended to set the international normalized ratio (INR) value of 2-3 with a daily INR check until the target INR is reached when the patient is first diagnosed with a giant aneurysm. Monthly INR testing is to be followed unless the patient is sick or undergoes a change in their medication or diet[14].

We reviewed the papers published regarding KD patients presenting with ACS. We first searched the PubMed database (search last updated in December 2021). The keywords were Kawasaki disease and acute coronary syndrome and case report. Among the 337 studies that were found, we excluded cases with patients under the age of 18 years and papers written in languages other than English. Among the 30 cases with these conditions, we further selected 18 cases from 14 publications with definite diagnoses (19 cases from 15 publications, including our own) (Table 2)[22-35].

| Ref. | Age/Sex/Age of KD diagnosis | CV risk factor | Thromboprophylaxis | Follow up | Coronary angiography | Maximal diameter | Treatment |

| Current case | 35/M/2 | - | - | - | Aneurysm in the LCX, RCA. Stenosis in the LCX | 6.0 mm | PCI |

| Jiang et al[22] | 21/F/2 | - | - | - | Aneurysm in the mid-RCA. Thrombosis in the RCA | - | Medication |

| Rozo et al[23] | 36/M/4 | DL | - | - | Aneurysm in the left main and proximal LAD. Stenosis in the proximal LAD | - | CABG |

| Negoro et al[24] | 27/M/1 | - | - | - | Aneurysm in all coronary arteries. Total occlusion in the mid-RCA | - | Thrombectomy and balloon angioplasty |

| Negoro et al[24] | 32/M/2 | Smoker | - | + | Aneurysm in all coronary arteries. Stenosis in proximal the LCX and occlusion in the mid-RCA | - | Directional coronary atherectomy and balloon angioplasty |

| Shaukat et al[25] | 24/M/6 | - | - | - | Aneurysm in the RCA and LCX. Occlusion in the proximal LAD, distal LCX and mid RCA | 17.0 mm | Thrombolysis |

| Ariyoshi et al[26] | 26/M/3 | Smoker | - | - | Aneurysm in the proximal LAD. Total occlusion in the proximal LAD | 9.0 mm | PCI |

| Tsuda et al[27] | 26/M/0 | Smoker | - | - | Aneurysm in the RCA, LAD and LCX. Total occlusion in the left main | 8.1 mm | Thrombolysis |

| Tsuda et al[27] | 24/M/1 | - | - | + | Aneurysm in the bifurcation of the left coronary artery and proximal LAD. No significant stenosis | - | Medication |

| Kodama et al[28] | 25/M/7 | Smoker | - | - | Aneurysm in the LAD and LCX. Occlusion in the LAD and LCX | - | Thrombolysis |

| Kawai et al[29] | 32/M/4 | Smoker | - | - | Aneurysm in the LAD. Total occlusion in the proximal LAD | 5.8 mm | PCI |

| Kawai et al[29] | 34/M/3 | - | - | - | Aneurysm in the LAD. Total occlusion in the proximal LAD | - | PCI |

| Shiraishi et al[30] | 26/M/3 | - | - | - | Aneurysm in the proximal LAD. Total occlusion in the proximal LAD | 8.0 mm | Balloon angioplasty |

| Vijayvergiya et al[31] | 20/M/9 | - | - | - | Aneurysm in the proximal LAD. There was no stenosis in the coronary artery | 13.0 mm | CABG |

| Sato et al[32] | 44/M/3 | - | - | - | Aneurysm in the proximal LAD. Occlusion in the LM | 8.0 mm | PCI |

| Kitamura et al[33] | 20/M/3 | - | - | + | Aneurysm in the LAD. Stenosis in the LAD and RCA | 19.0 mm | CABG |

| Kitamura et al[33] | 30/M/0 | - | - | + | Aneurysm in the RCA. Stenosis in the RCA | 30.0 mm | CABG |

| Potter et al[34] | 36/F/4 | - | - | - | Aneurysm in the proximal LAD, RCA. Occlusion in the RCA | 8.0 mm | CABG |

| Motozawa et al[35] | 24/M/4 | - | Aspirin and ticlopidine | + | Aneurysm in the LAD. Stenosis in the LAD | 9.0 mm | Thrombectomy |

In this case series, the average age of initial KD diagnosis was 3.2 ± 2.2 years. MI occurred at 28.5 ± 6.3 years of age, and the mean maximal diameter of the CAA was 11.7 mm ± 6.8 mm. Among a total of 19 patients, 4 (21.1%) patients underwent coronary stenting (1 Korea and 3 Japanese patients). After the diagnosis of KD, regular follow-up until adulthood was only performed in 5 of 19 cases (26.3%). Although a regular follow-up is recommended by expert consensus, there is limited evidence as to whether it translates to improved outcomes. However, a more concerted effort in this arena appears to be crucial, as patients diagnosed with KD are often neglected or lost to follow-up even in specialized centers. In a survey of 104 United States pediatric hospitals of patients with KD, only 10% of patients were referred to a cardiologist, and the majority of patients (79%) did not undergo a third echocardiographic evaluation, suggesting that such patients were lost to follow-up[36]. Moreover, only 4% of patients were managed according to the guidelines in a United States tertiary hospital[36]. A Japanese survey of KD experts in 2014 showed that 90% of the respondents considered it necessary for patients with KD to consult a cardiologist regularly in adulthood if there was a coronary artery lesion[37]. More than 40% of patients did not undergo regular examinations during adulthood.

In patients with CAA, if the Z score is greater than 2.5, a transition to adult cardiac follow-up is required at the age of 16 to 18 years[9]. Notably, none except for the current patient among the 19 patients presented with Z scores (Table 2). The maximal diameter was measured in only 12 patients, including the current patient, out of 19 patients (63%). However, considering that the mean maximal diameter (11.7 mm ± 6.8 mm) of the 12 patients was above 10 mm, the CAAs were giant aneurysms by definition and were indicated for both anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. This suggests once more that physicians worldwide may be relatively unaware of the Z score or the importance of maximal diameter in relation to long-term outcomes[36]. Our patient also had a Z score of 4.7 in his LCX; however, the patient was not evaluated until MI occurred and was not being treated with antithrombotic therapy.

Additionally, most KD patients may not be under thromboprophylaxis treatment despite it being indicated. Although there is limited information regarding the percentage of patients under antithrombotic therapy in the literature, our study of the case series suggests that a very low percentage of patients (1 out of 19 patients, 5.3%) underwent thromboprophylaxis (Table 2). Since the disease is rare, it appears that physicians are commonly unaware of the long-term evaluation and management of KD, such that governmental initiatives may be necessary to educate and promote physicians and caregivers for both primary and secondary prevention.

The use of IVUS is recommended during PCI in KD patients with ACS by expert consensus[14]. PCI with IVUS can confirm the exact vascular pathology and diameter of vessel[38]. The IVUS helps stent deployment during coronary intervention and anticoagulation after procedure[14]. In our patient, we used IVUS during the procedure because we did not have a good visual on distal OM and to confirm the underlying pathophysiology.

From the current case and the case series of 19 KD patients who presented with ACS, we found that proper long-term medical care had not been provided, including regular examination and medical therapy. For KD presenting with ACS, regular follow up and medical therapy may be crucial for improved outcomes.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dauyey K, Kazakhstan; Hu F, China; Ito S, Japan; Li Y, China S-Editor: Wang DM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang DM

| 1. | Burns JC, Glodé MP. Kawasaki syndrome. Lancet. 2004;364:533-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 723] [Cited by in RCA: 682] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nakamura Y. Kawasaki disease: epidemiology and the lessons from it. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:16-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim GB, Park S, Eun LY, Han JW, Lee SY, Yoon KL, Yu JJ, Choi JW, Lee KY. Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Kawasaki Disease in South Korea, 2012-2014. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36:482-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu MH, Chen HC, Yeh SJ, Lin MT, Huang SC, Huang SK. Prevalence and the long-term coronary risks of patients with Kawasaki disease in a general population <40 years: a national database study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:566-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abrams JY, Belay ED, Uehara R, Maddox RA, Schonberger LB, Nakamura Y. Cardiac Complications, Earlier Treatment, and Initial Disease Severity in Kawasaki Disease. J Pediatr. 2017;188:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fukazawa R, Kobayashi J, Ayusawa M, Hamada H, Miura M, Mitani Y, Tsuda E, Nakajima H, Matsuura H, Ikeda K, Nishigaki K, Suzuki H, Takahashi K, Suda K, Kamiyama H, Onouchi Y, Kobayashi T, Yokoi H, Sakamoto K, Ochi M, Kitamura S, Hamaoka K, Senzaki H, Kimura T; Japanese Circulation Society Joint Working Group. JCS/JSCS 2020 Guideline on Diagnosis and Management of Cardiovascular Sequelae in Kawasaki Disease. Circ J. 2020;84:1348-1407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sundel RP. Kawasaki disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:63-73, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Senzaki H. The pathophysiology of coronary artery aneurysms in Kawasaki disease: role of matrix metalloproteinases. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:847-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brogan P, Burns JC, Cornish J, Diwakar V, Eleftheriou D, Gordon JB, Gray HH, Johnson TW, Levin M, Malik I, MacCarthy P, McCormack R, Miller O, Tulloh RMR; Kawasaki Disease Writing Group, on behalf of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the British Cardiovascular Society. Lifetime cardiovascular management of patients with previous Kawasaki disease. Heart. 2020;106:411-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Burns JC, Shike H, Gordon JB, Malhotra A, Schoenwetter M, Kawasaki T. Sequelae of Kawasaki disease in adolescents and young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:253-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Daniels LB, Tjajadi MS, Walford HH, Jimenez-Fernandez S, Trofimenko V, Fick DB Jr, Phan HA, Linz PE, Nayak K, Kahn AM, Burns JC, Gordon JB. Prevalence of Kawasaki disease in young adults with suspected myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2012;125:2447-2453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kavey RE, Allada V, Daniels SR, Hayman LL, McCrindle BW, Newburger JW, Parekh RS, Steinberger J; American Heart Association Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism; American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on the Kidney in Heart Disease; Interdisciplinary Working Group on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science; the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Epidemiology and Prevention, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, High Blood Pressure Research, Cardiovascular Nursing, and the Kidney in Heart Disease; and the Interdisciplinary Working Group on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2006;114:2710-2738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 525] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kobayashi T, Fuse S, Sakamoto N, Mikami M, Ogawa S, Hamaoka K, Arakaki Y, Nakamura T, Nagasawa H, Kato T, Jibiki T, Iwashima S, Yamakawa M, Ohkubo T, Shimoyama S, Aso K, Sato S, Saji T; Z Score Project Investigators. A New Z Score Curve of the Coronary Arterial Internal Diameter Using the Lambda-Mu-Sigma Method in a Pediatric Population. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29:794-801.e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, Burns JC, Bolger AF, Gewitz M, Baker AL, Jackson MA, Takahashi M, Shah PB, Kobayashi T, Wu MH, Saji TT, Pahl E; American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Long-Term Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement for Health Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e927-e999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1586] [Cited by in RCA: 2440] [Article Influence: 305.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Friedman KG, Gauvreau K, Hamaoka-Okamoto A, Tang A, Berry E, Tremoulet AH, Mahavadi VS, Baker A, deFerranti SD, Fulton DR, Burns JC, Newburger JW. Coronary Artery Aneurysms in Kawasaki Disease: Risk Factors for Progressive Disease and Adverse Cardiac Events in the US Population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Miura M, Kobayashi T, Kaneko T, Ayusawa M, Fukazawa R, Fukushima N, Fuse S, Hamaoka K, Hirono K, Kato T, Mitani Y, Sato S, Shimoyama S, Shiono J, Suda K, Suzuki H, Maeda J, Waki K; The Z-score Project 2nd Stage Study Group, Kato H, Saji T, Yamagishi H, Ozeki A, Tomotsune M, Yoshida M, Akazawa Y, Aso K, Doi S, Fukasawa Y, Furuno K, Hayabuchi Y, Hayashi M, Honda T, Horita N, Ikeda K, Ishii M, Iwashima S, Kamada M, Kaneko M, Katyama H, Kawamura Y, Kitagawa A, Komori A, Kuraishi K, Masuda H, Matsuda S, Matsuzaki S, Mii S, Miyamoto T, Moritou Y, Motoki N, Nagumo K, Nakamura T, Nishihara E, Nomura Y, Ogata S, Ohashi H, Okumura K, Omori D, Sano T, Suganuma E, Takahashi T, Takatsuki S, Takeda A, Terai M, Toyono M, Watanabe K, Watanabe M, Yamamoto M, Yamamura K. Association of Severity of Coronary Artery Aneurysms in Patients With Kawasaki Disease and Risk of Later Coronary Events. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:e180030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dominguez SR, Anderson MS, El-Adawy M, Glodé MP. Preventing coronary artery abnormalities: a need for earlier diagnosis and treatment of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:1217-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rife E, Gedalia A. Kawasaki Disease: an Update. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mori M, Miyamae T, Imagawa T, Katakura S, Kimura K, Yokota S. Meta-analysis of the results of intravenous gamma globulin treatment of coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2004;14:361-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Manlhiot C, Newburger JW, Low T, Dahdah N, Mackie AS, Raghuveer G, Giglia TM, Dallaire F, Mathew M, Runeckles K, Pahl E, Harahsheh AS, Norozi K, de Ferranti SD, Friedman K, Yetman AT, Kutty S, Mondal T, McCrindle BW; International Kawasaki Disease Registry. Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin vs Warfarin for Thromboprophylaxis in Children With Coronary Artery Aneurysms After Kawasaki Disease: A Pragmatic Registry Trial. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:1598-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sugahara Y, Ishii M, Muta H, Iemura M, Matsuishi T, Kato H. Warfarin therapy for giant aneurysm prevents myocardial infarction in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:398-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jiang X, Li J, Zhang X, Chen H. Acute coronary syndrome in a young woman with a giant coronary aneurysm and mitral valve prolapse: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060521999525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rozo JC, Jefferies JL, Eidem BW, Cook PJ. Kawasaki disease in the adult: a case report and review of the literature. Tex Heart Inst J. 2004;31:160-164. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Negoro N, Nariyama J, Nakagawa A, Katayama H, Okabe T, Hazui H, Yokota N, Kojima S, Hoshiga M, Morita H, Ishihara T, Hanafusa T. Successful catheter interventional therapy for acute coronary syndrome secondary to kawasaki disease in young adults. Circ J. 2003;67:362-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shaukat N, Ashraf S, Mebewu A, Freemont A, Keenan D. Myocardial infarction in a young adult due to Kawasaki disease. A case report and review of the late cardiological sequelae of Kawasaki disease. Int J Cardiol. 1993;39:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ariyoshi M, Shiraishi J, Kimura M, Matsui A, Takeda M, Arihara M, Hyogo M, Shima T, Okada T, Kohno Y, Sawada T, Matsubara H. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction due to possible sequelae of Kawasaki disease in young adults: a case series. Heart Vessels. 2011;26:117-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tsuda E, Hanatani A, Kurosaki K, Naito H, Echigo S. Two young adults who had acute coronary syndrome after regression of coronary aneurysms caused by Kawasaki disease in infancy. Pediatr Cardiol. 2006;27:372-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kodama K, Okayama H, Tamura A, Suetsugu M, Honda T, Doiuchi J, Hamada N, Nomoto R, Akamatsu A, Jo T. Kawasaki disease complicated by acute myocardial infarction due to thrombotic occlusion of coronary aneurysms 19 years after onset. Intern Med. 1992;31:774-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kawai H, Takakuwa Y, Naruse H, Sarai M, Motoyama S, Ito H, Iwase M, Ozaki Y. Two cases with past Kawasaki disease developing acute myocardial infarction in their thirties, despite being regarded as at low risk for coronary events. Heart Vessels. 2015;30:549-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shiraishi J, Harada Y, Komatsu S, Suzaki Y, Hosomi Y, Hirano S, Sawada T, Tatsumi T, Azuma A, Nakagawa M, Matsubara H. Usefulness of transthoracic echocardiography to detect coronary aneurysm in young adult: two cases of acute myocardial infarction due to Kawasaki disease. Echocardiography. 2004;21:165-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Vijayvergiya R, Bhattad S, Varma S, Singhal M, Gordon J, Singh S. Presentation of missed childhood Kawasaki disease in adults: Experience from a tertiary care center in north India. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20:1023-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sato T, Isomura T, Hayashida N, Aoyagi S. Coronary artery revascularization in an adult with coronary aneurysms probably secondary to childhood Kawasaki disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;12:312-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kitamura A, Mukohara N, Ozaki N, Yoshida M, Shida T. Two adult cases of coronary artery aneurysms secondary to Kawasaki disease. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56:57-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Potter EL, Meredith IT, Psaltis PJ. ST-elevation myocardial infarction in a young adult secondary to giant coronary aneurysm thrombosis: an important sequela of Kawasaki disease and a management challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Motozawa Y, Uozumi H, Maemura S, Nakata R, Yamamoto K, Takizawa M, Kumagai H, Ikeda Y, Komuro I, Ikenouchi H. Acute Myocardial Infarction That Resulted From Poor Adherence to Medical Treatment for Giant Coronary Aneurysm. Int Heart J. 2015;56:551-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lowry AW, Knudson JD, Myones BL, Moodie DS, Han YS. Variability in delivery of care and echocardiogram surveillance of Kawasaki disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2012;7:336-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kamiyama H, Ayusawa M, Ogawa S, Saji T, Hamaoka K. Health-care transition after Kawasaki disease in patients with coronary artery lesion. Pediatr Int. 2018;60:232-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gordon JB, Daniels LB, Kahn AM, Jimenez-Fernandez S, Vejar M, Numano F, Burns JC. The Spectrum of Cardiovascular Lesions Requiring Intervention in Adults After Kawasaki Disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |