Published online Sep 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.9132

Peer-review started: April 26, 2022

First decision: June 16, 2022

Revised: June 25, 2022

Accepted: July 22, 2022

Article in press: July 22, 2022

Published online: September 6, 2022

Processing time: 122 Days and 5.1 Hours

Chondrosarcoma of the foot is a rare malignant bone tumour, and it is even rarer when it originates in a toe bone. Surgical excision is the only effective treatment. The osteolytic destruction of the tumour severely affects limb function and carries the risk of distant metastasis. Most such tumours are removed surgically to minimize local recurrence and distant metastases, maximize limb function, and prolong the patient's tumour-free survival time. The main objective of this article is to present the case of a chondrosarcoma that invaded the first phalanx of the left foot and formed a large phalangeal mass with osteolytic destruction of the distal bone.

A 74-year-old man suffered from swelling of his left toe for six months, with pain and swelling for two months. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging showed that the tumour on the first phalanx of the left foot was approximately 54.9 mm × 44.6 mm, surrounded by a significant soft tissue signal mass, with osteolytic destruction of the distal phalanx and a speckled bone-like high-density shadow within it.

Chondrosarcoma occurring in a toe bone is extremely rare. In this case, extensive surgical resection of the large low-grade chondrosarcoma, which showed osteolytic destruction and invaded the distal metatarsal bone, was safe and effective.

Core Tip: The main objective of this article is to present a case of chondrosarcoma that invaded the first phalanx of the left foot and formed a sizeable phalangeal mass with osteolytic destruction of the distal bone. Chondrosarcoma originating in a toe bone has only been sporadically reported, and this case report will help clinicians better understand this rare lesion.

- Citation: Zhou LB, Zhang HC, Dong ZG, Wang CC. Chondrosarcoma of the toe: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(25): 9132-9141

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i25/9132.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i25.9132

Chondrosarcoma is the second most common primary malignant tumour of bone, accounting for approximately 25% of all primary bone tumours. It has an annual incidence of approximately 6.63 per 1 million people and is characterized by the production of tumourigenic cartilage[1-3]. Chondrosarcoma can occur at any age, with a mean age of 50 years, and it affects slightly more men than women (55%: 45%)[4]. The anatomical sites most commonly involved in chondrosarcoma include the long tubular bone (40%), pelvis (25%), and scapula[3,5].

Chondrosarcoma of the foot is a rare malignant bone tumour. One study found that the prevalence of chondrosarcoma of the foot is approximately 3.0%, with the highest prevalence in the metatarsal bone, and the overall survival of chondrosarcoma of the foot is better than that of chondrosarcoma of other anatomical sites[6]. It is even rarer when it arises in phalanges, the incidence of which has not been clearly established and has rarely been reported in the literature. Chondrosarcoma is insensitive to radiation and chemotherapy; thus, surgery remains the preferred treatment modality. This case report expands the literature on chondrosarcoma of the toe and will help clinicians better understand this rare lesion.

A 74-year-old man suffered from swelling of his left toe for six months, with pain and swelling for two months.

A painless left calcaneal mass observed over six months presented with a rapidly enlarging mass, a significant increase in size, and localized symptoms of pain and swelling for two months.

He reported that he had noticed a mass on the lesser toe of his left foot that had gradually increased in size over the past six months and was not taken seriously.

He had no family history of chondrosarcoma disease or any other disease.

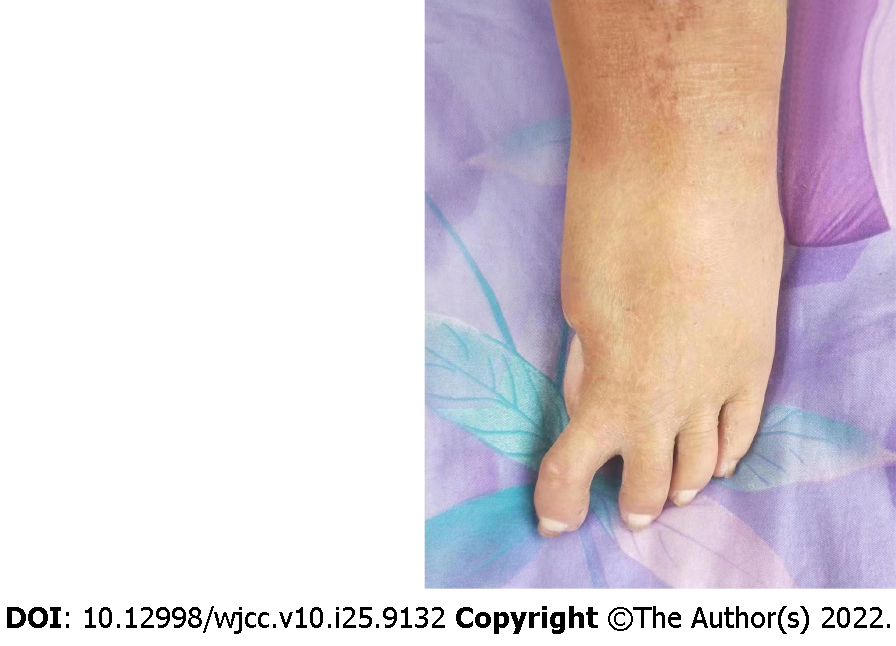

Physical examination showed swelling of the left calcaneus and a palpable round mass of approximately 60.0 mm x 50.0 mm in size with a mallet-like appearance. The mass was soft, with tenderness on palpation and indistinct borders. The movement of the interphalangeal joint and the metatarsophalangeal joint was limited. Other physical examination findings were normal.

The results of routine blood tests and biochemical tests were normal.

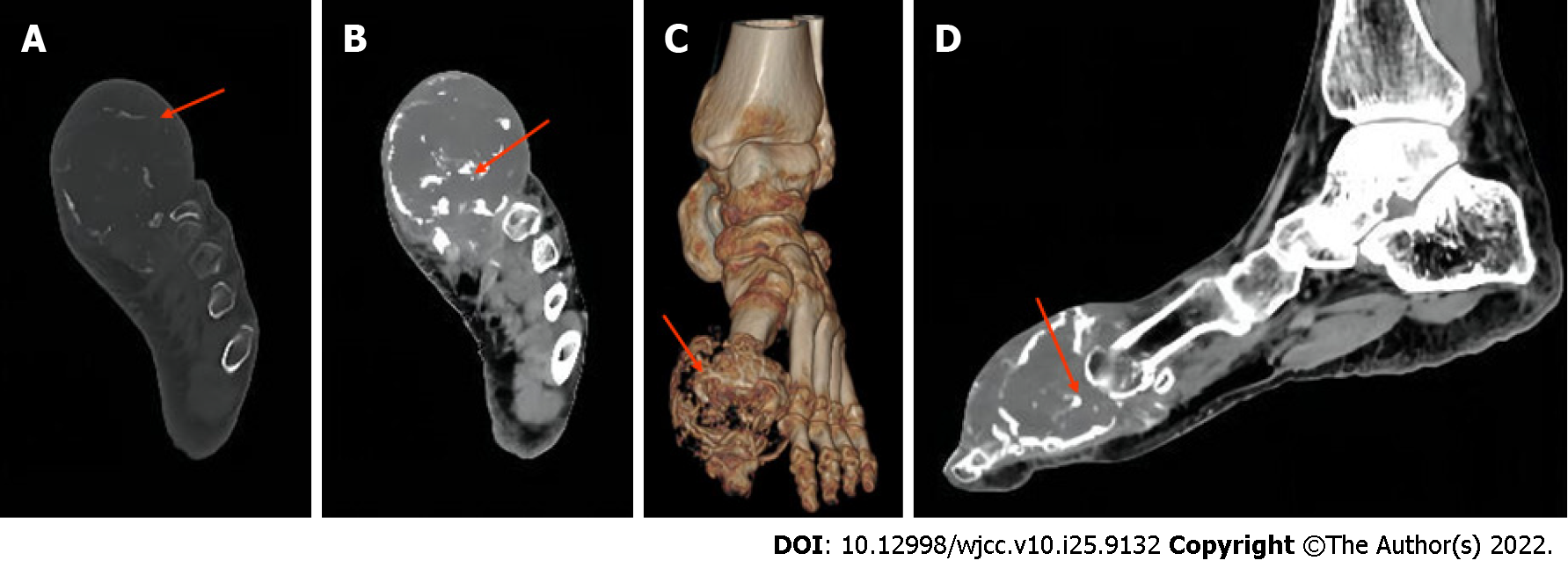

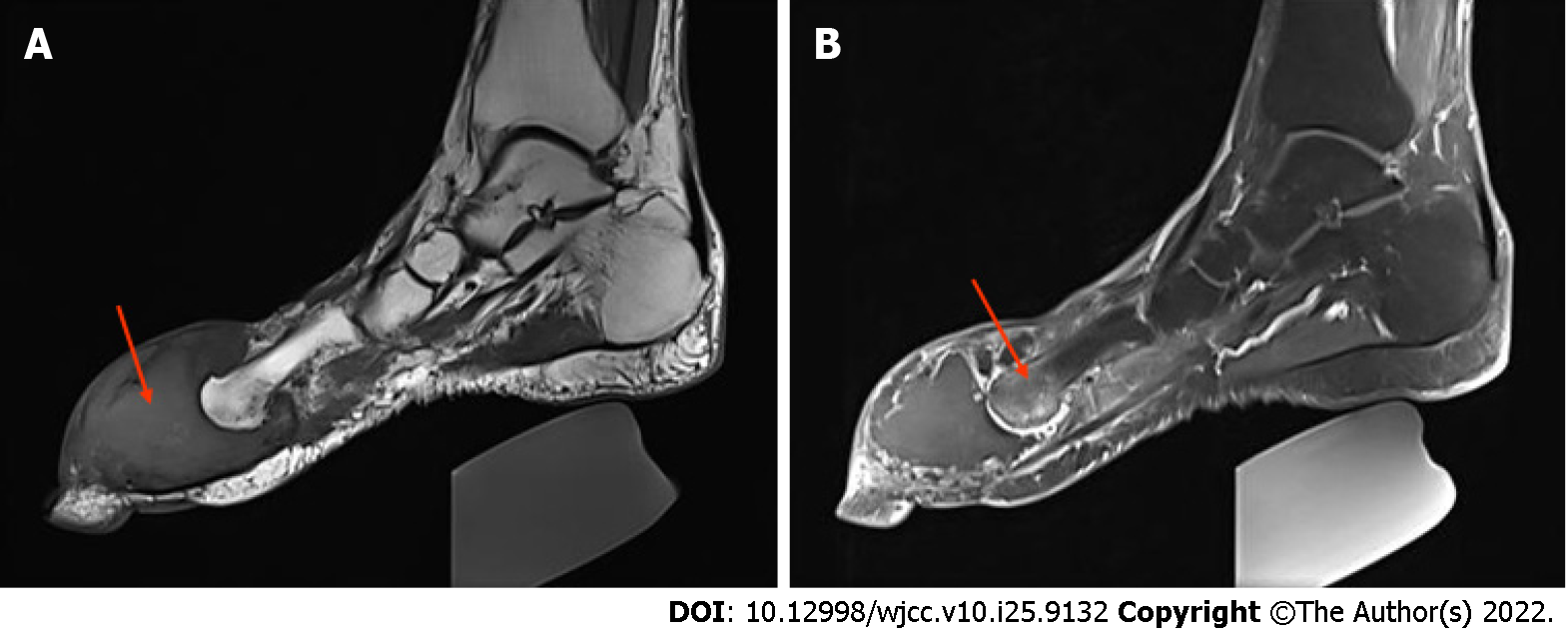

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large tumour in the first phalanx of the left foot. A CT scan showed osteolytic destruction of the distal bone of the first phalanx of the left foot, with a local soft tissue density mass of approximately 54.9 mm × 44.6 mm, a local CT value of approximately 21 HU, and a speckled bone-like high-density shadow within it (Figure 1). MRI + enhancement showed that the typical shape of the first phalanx of the left foot had disappeared, and a large soft tissue signal mass with equal length T1 Weighted Image (T1WI) signals was seen around it (Figure 2).

The final diagnosis was chondrosarcoma.

The preoperative imaging findings were suggestive of malignant occupancy of the first phalanx of the left foot with the possible distal invasion of the adjacent metatarsals. All routine blood tests, biochemical tests, and chest radiographs were within normal limits, and parallel CT examinations of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed no metastatic lesions or other tumourigenic lesions.

The patient and his family were informed of his condition based on the imaging findings and clinical symptoms. Due to the possibility of invasion of the adjacent distal metatarsal bone, the patient was advised to undergo extensive resection, and the patient and his family agreed. A joint surgeon performed the surgical treatment. The surgeon performed an osteotomy of the first phalanx of the left foot and distal bone removal of the adjacent metatarsal. The tumour tissue was excised and sent for histopathological examination.

The pathological result was reported as highly differentiated cartilaginous sarcoma (low-grade malignancy) (Figure 3). The patient was followed up for 30 mo after surgery, and the patient was in good condition with no tumour recurrence or distant metastasis (Figure 4).

Chondrosarcoma is a malignant tumour of mesenchymal cell origin that can be primary or secondary to benign cartilage tumours[7]. A common clinical symptom of chondrosarcoma is localized pain with or without a significant mass. Local pain is an essential feature for distinguishing chondrosarcoma from benign cartilage tumours. This pain is thought to be caused by invasive growth of the chondrosarcoma, and the pain increases with increasing malignancy. At first, the pain is often intermittent and mild, and then it gradually develops into persistent severe pain, nocturnal pain, and tenderness. When the tumours is located close to the joint, the movement of the joint can be limited, and the surrounding soft tissue mass can be easily palpated.

Early diagnosis facilitates effective treatment and improves the prognosis of patients with chondrosarcoma. In addition to the above nonspecific symptoms and signs, the diagnosis of chondrosarcoma mainly relies on imaging evaluation and histopathological characterization. Compared with X-rays, CT is more reliable and sensitive for diagnosing chondrosarcoma, especially with small tumours or tumours that have complex anatomical locations. CT is superior to X-rays for the detection of calcifications[8]. The most common manifestations of chondrosarcoma on X-ray or CT are "ring", "arc," or "popcorn" calcifications and invasive growth; osteolytic changes are also common[9]. The specific imaging signs depend on the type and grade of the chondrosarcoma. Calcification of high-grade chondrosarcoma is rare.

For example, intramedullary chondrosarcoma often presents with osteolytic changes and osteosclerosis, often accompanied by calcification. In clear cell chondrosarcoma, calcification occurs in only 30% of cases. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma shows a "biphasic sign" on X-ray or CT. Its imaging manifestations are closely related to the two pathological components in the tumour and depends on the proportion of low-grade and high-grade areas of the lesion[8,10]. MRI is superior to the other techniques in terms of soft-tissue contrast. In typical cases, the edges of the lesion may show lobulated changes with a low or medium signal on T1WI and a high signal on T2 Weighted Image. The combination of MRI diffusion-weighted imaging and enhancement also allows for accurate staging of the lesion. Low-grade lesions tend to show interval and peripheral enhancement, whereas high-grade lesions tend to show diffuse enhancement of the solid component of the lesion, mostly accompanied by a large nonenhancing necrotic shadow[11].

Pathological classification of chondrosarcoma, according to the WHO classification of bone and soft tissue tumours in 2020, is divided into conventional, periosteal, and clear cell mesenchymal and dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma. Conventional chondrosarcoma is divided into grades I, II, and III[12]. Eighty-five percent of chondrosarcomas are primary and of the conventional type[1]. Chondrosarcomas are central (intramedullary), periosteal, or peripheral according to their location in the bone. Chondrosarcomas are classified into primary and secondary chondrosarcomas by the source[13]. Since the recurrence rate and prognosis of tumours after surgery for intermediate (locally invasive) atypical cartilaginous tumour/chondrosarcoma grade I (atypical cartilaginous tumour, ACT/chondrosarcoma grade I, CS1) differ significantly from site to site, mainly because the location of the tumour determines the prognosis, the new version of the guidelines split atypical cartilaginous tumour/chondrosarcoma grade I into ACT and CS1 based on the anatomical location, with the former retained in the intermediate type and the latter upgraded to malignant disease. The diagnosis of ACT occurring in the tubular bones of the extremities and the diagnosis of CS1 occurring in the mesial bones, such as the skull base, pelvis, and scapula, suggest the need for complete surgical resection[14].

Chondrosarcoma histological grade (Evans grade) is categorized as grade I (low grade), grade II (intermediate grade), or grade III (high grade). Grade I and II chondrosarcoma have a good prognosis, while grade III chondrosarcoma has a high recurrence and metastasis rate[15]. Grossly, the growth is lobulated, the cut surface is translucent or white with hyaline brittle tissue or even gel-like mucus, and cystic changes can be seen. It can be sandy due to calcification and can be rigid or soft. Microscopically, the density of grade I chondrocytes is low, the nucleus is fat and deeply stained, binucleate cells are occasionally seen, and there are no mitotic images. The density of grade II chondrocytes is increased, the nucleus is increased, the chromatin is thickened, heteromorphism and binucleate cells appear, and mitotic images can be seen. Grade III has a high cell density, with prominent atypia, pleomorphism, and mitotic images. Spindle cells around the leaflets are immature. Mutations of isocitrate dehydrogenase type 1 (IDH1) or isocitrate dehydrogenase type 2 (IDH2) may exist in primary central chondrosarcoma and periosteal chondrosarcoma[16].

Secondary chondrosarcoma originates from osteochondroma or endogenous chondrosarcoma. Clinically, they present as new painful episodes of existing lesions, and their histological presentation is indistinguishable from that of primary conventional chondrosarcoma. Osteochondroma is one of the most common benign tumors of bone. Multiple cases often have a family history called hereditary multiple osteochondromas (HMOs), also known as hereditary multiple exostoses. HMO is an autosomal dominant inherited abnormality of skeletal development[17]. Osteochondromas account for approximately 80% or more of secondary chondrosarcomas. The average age at diagnosis is 35 years, which is much younger than that for primary chondrosarcoma.

For patients with isolated exophytic warts, the lifetime risk of malignant transformation is approximately 0.4%-2%, compared to 5%-25% for patients with HMO[18]. The cartilage cap indicates tumour malignancy, and MRI can show this structure. A larger cartilage cap can indicate malignancy, but there is no significant correlation between the thickness of the cartilage cap and the malignancy rate in young patients[19]. One study showed that for cartilage caps of approximately 2 cm, the sensitivity and specificity of MRI and CT were 100% and 98% and 100% and 95%, respectively[20]. However, imaging and clinical aspects are vital because marginal cartilage caps with stable clinical and imaging presentation are unlikely to be cancerous, whereas rapid enlargement may indicate malignant changes.

Chondroma is a common benign tumour of bone. Cases that occur in the bone marrow cavity are called endogenous chondroma, and those that occur on the bone surface are called periosteal chondroma. This disease can have single or multiple lesions, and cases with multiple lesions are called endogenous chondromatosis. Endogenous chondromatosis combined with skeletal deformities is called Ollier's disease, whereas endogenous chondromatosis combined with soft tissue (and occasionally visceral) haemangiomas of the limbs is called Maffucci syndrome[21].

Both diseases are nonhereditary benign diseases and are related to gene mutations of IDH1 or IDH2[22]. Solitary endophytic chondroma has a 1-9% risk of malignant transformation. Approximately 40% of Ollier's disease cases and more than 50% of Maffucci syndrome cases can be secondary to chondrosarcoma[23]. Almost all patients with Maffucci syndrome will develop malignant trans

Özmanevra et al[25] reported a patient initially diagnosed with endogenous chondroma who received curettage and bone grafting. The tumour recurred locally seven months after the operation and was then diagnosed as grade 2 chondrosarcoma, followed by resection of the proximal phalanx of the third toe. At the one-year follow-up, the patient survived tumour-free. Therefore, lifelong monitoring is required for patients with endogenous chondromatosis.

It remains controversial which factors affect the prognosis of chondrosarcoma, but tumour grading has clear prognostic significance. The survival and metastatic potential of chondrosarcoma are closely related to histological grade. Evans et al[15] found 10-year survival rates of 83%, 64%, and 29% for grade I, II, and III chondrosarcomas, respectively. There were 40%, 60%, and 47% local recurrence rates for low, medium, and high grades, respectively. The metastasis rate is low for low-grade chondrosarcomas, 10% for intermediate-grade metastases, and 71% for high-grade metastases. Patients undergoing margin-negative surgery have a reduced risk of local tumour recurrence and improved survival. However, even if they undergo margin-negative surgery, patients with grade III chondrosarcoma will eventually die from recurrence and metastasis[26].

The current case is a 74-year-old male patient with a disease course of 8 mo. Although most of the tumour cells were well differentiated (mildly heterogeneous chondrocytes) and mitotic images were rare, cortical destruction and soft tissue expansion were apparent. Therefore, the patient underwent extensive surgical resection. The patient was free of tumor tumour recurrence and distant metastasis at the 30 mo postoperative follow-up. The most current version of the guideline diagnoses ACT/CS1 occurring in tubular bones of the extremities as ACT because of its relatively short anatomy, relatively easy surgical resection, maximum negative margins, and significantly lower tumour recurrence rate. Hence, patients have a longer tumour-free survival time.

Surgical resection remains the treatment of choice for primary or secondary chondrosarcoma. According to the Enneking staging[27], surgical resection is classified as local, extensive, or radical resection. Local resection includes intracapsular curettage and marginal resection, intracapsular curettage is used for central tumours, and marginal resection is used for peripheral tumours. Local excision is used when the tumour is distant from the joint when cortical destruction and soft tissue invasion are not severe. Extensive resection is used when the tumour is close to the joint, has cortical destruction, or has severe soft tissue invasion. When anatomically permitted, the critical treatment for chondrosarcoma is a radical operation; that is, the margin of the resected malignant tumour is negative under the microscope. According to Laitinen et al[28], complete surgical resection reduces the risk of local recurrence of the tumour.

Chondrosarcoma originating in the toe bone is usually of low grade (grade I), but controversy still exists regarding the surgical approach to grade I chondrosarcoma. According to the latest guidelines, some surgeons suggest that intrathecal curettage and local adjuvant treatment should be adopted for treating the tubular bones of limbs, such as electric knife cauterization, bone cement, high-speed grinding, drilling, ethanol, phenol, and liquid nitrogen[2,29].

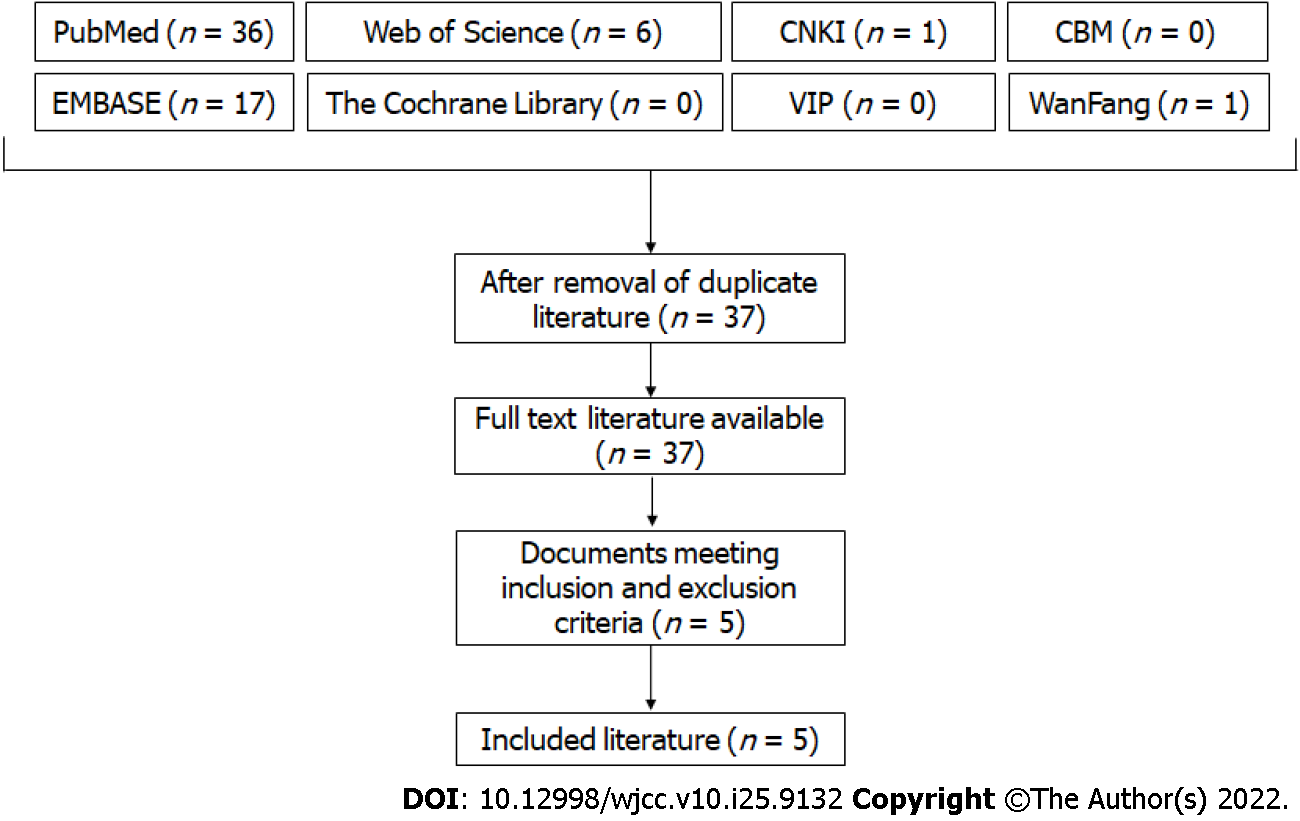

We searched the following 8 databases: four English medical databases [MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Cochrane Library)], Web of Science Database, and four Chinese medical databases [the China National Knowledge Database (CNKI), Journal Integration Platform (VIP), WanFang Database and SinoMed (CBM]). We also manually searched the additional relevant studies using the references of the systematic reviews that were published previously. All of the searches were performed from inception to April 2022 and did not impose restrictions on language, population or country. The following search strategy was used for PubMed and was modified to suit other databases.

#1 (chondrosarcoma[Title/Abstract])

#2 (Toe [Title/Abstract])

#1 AND #2

Literature inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The site of the disease was in the toe; (2) Pathologically diagnosed as chondrosarcoma; (3) Chondrosarcoma was the main lesion; and (4) Not combined with other malignant diseases. Figure 5 illustrates the study selection process.

Searching the relevant database, there were 5 cases of chondrosarcoma of the phalanx. Two of the patients had grade 1 chondrosarcoma. The patients underwent resection of the first phalanx of the right foot or resection of the mass on the first phalanx of the left foot with scraping of the proximal phalanx. At the 1-year postoperative follow-up, none of the patients had local recurrence or distant metastases[30,31]. Masuda et al[32] reported a case of primary grade 2 chondrosarcoma in which the patient underwent resection of the distal half of the second proximal phalanx of the right foot. There was no evidence of recurrence or metastasis at two years of follow-up. Özmanevra et al[25] reported a secondary grade 2 chondrosarcoma case with proximal phalangeal resection of the lesser toe. At the one-year follow-up, the patient was tumour-free. We found that patients with grade 2 chondrosarcoma of the toe bone had a better prognosis than those with chondrosarcoma of other sites. In addition, studies have shown that the prognosis of secondary chondrosarcoma is similar to that of primary chondrosarcoma, and the 5-year survival rate is approximately 90%[19]. It has been suggested that the flexor and extensor tendon sheaths are natural barriers that limit the spread of toe tumours; thus, metastases are uncommon[24]. The recurrence rate and metastasis rate of grade 3 chondrosarcoma are relatively high. Rafi et al[33] reported that a patient with grade 3 chondrosarcoma of the right foot and toe underwent amputation treatment. Left orbital and left infratemporal metastasis occurred, causing swelling and pain and gradual vision loss in the left eye.

A literature review showed that the local recurrence rate was only 0%-7.7% when intracapsular curettage was used for the resection of central low-grade chondrosarcoma of the limbs[34]. Chen et al[3] showed that intracapsular curettage was a safe and functional method for treating central primary grade I chondrosarcoma. Lesenský et al[35] concluded that curettage is the treatment of choice for ACT/Grade I tumours; however, surgeons should be aware of the potentially high local recurrence and recurrence rates. Resection is recommended for Grade II and Grade III chondrosarcomas. However, the Dierselhuis et al[36] meta-score noted that the current level of evidence does not yet adequately support local excision as a treatment modality for low-grade chondrosarcoma of the extremities. For grade II and III chondrosarcomas, extensive resection with negative margins should be performed[37]. Although chondrosarcoma of the foot has a low risk of recurrence and metastasis, all patients require long-term follow-up. The previously reported cases are listed in Table 1.

| Ref. | Gender | Age, yr | Symptoms | Tumor Location | Histological grading | Treatment | Follow-up |

| Mondal[30] | Male | 37 | The right big toe was gradually swollen and painful for nearly two years | Distal end of the first phalange of the right foot | Grade I | Excision of the big toe at the metatarsophalangeal joint | Followed up for 1 yr, there was no tumor recurrence or metastasis |

| Haliloglu et al[31] | Female | 19 | Painless swelling of the left big toe for 6 yr | First phalanx of the left foot | Grade I | The mass was completely removed and the proximal phalanx was scraped | Followed up for 1 yr, there was no tumor recurrence or metastasis |

| Özmanevra et al[25] | Female | 52 | Swelling of the left big toe | First phalanx of the left foot | Grade II | Excision of the proximal phalanx | Followed up for 1 yr, there was no tumor recurrence or metastasis |

| Masuda et al[32] | Female | 32 | Pain, swelling and nail deformity of the second toe of the right foot for 6 mo | Second phalangeal bone of the right foot | Grade II | Resection of the distal part of the second proximal phalanx | Followed up for 2 yr, there was no tumor recurrence or metastasis |

| Rafi et al[33] | Male | 56 | Pain, swelling and ill defined mass on the right toe | First phalangeal bone of the right foot | Grade III | Amputation (specific location unknown) | Left orbital and left infratemporal metastasis |

Chondrosarcomas are considered radiation-resistant tumours. However, the exact mechanism has not been clarified. Several ideas have been proposed, such as the ability to inhibit reactive oxygen species and the high expression of antiapoptotic genes[38,39]. Goda et al[40] showed that preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy as an adjuvant treatment could reduce local tumour recurrence. Therefore, radiotherapy can be administered to patients with inoperable or incomplete resection and tumour recurrence, but its therapeutic significance is not yet supported by high-level clinical evidence. Chemotherapy is usually ineffective for chondrosarcoma, especially for conventional and dedifferentiated types. In the future, protein inhibitors targeting altered molecular pathways and mutated genes may become a focus for targeted therapies.

Chondrosarcoma is a rare malignant bone tumour, and it is even rarer when it occurs in a toe. Local excision is feasible for low-grade chondrosarcoma of the phalanx, which can minimize surgical trauma while preserving the function and aesthetics of the limb. However, considering the risk of tumour recurrence and metastasis, clinicians should carefully select cases that are not obviously aggressive on imaging, and for patients with chondrosarcoma of grades I (aggressive), II, and III, extensive excision with negative margins is the preferred initial treatment.

First, we would like to thank the patients and their families for their participation and the faculty members who provided imaging and pathology information for writing this article.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Di Meglio L, Italy; Vahedi M, Iran S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Laitinen MK, Evans S, Stevenson J, Sumathi V, Kask G, Jeys LM, Parry MC. Clinical differences between central and peripheral chondrosarcomas. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B:984-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Weinschenk RC, Wang WL, Lewis VO. Chondrosarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:553-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen X, Yu LJ, Peng HM, Jiang C, Ye CH, Zhu SB, Qian WW. Is intralesional resection suitable for central grade 1 chondrosarcoma: A systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:1718-1726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hua KC, Hu YC. Treatment method and prognostic factors of chondrosarcoma: based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9:4250-4266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wellings EP, Mallett KE, Parkes CW, Labott JR, Rose PS, Houdek MT. Impact of tumour stage on the surgical outcomes of scapular chondrosarcoma. Int Orthop. 2022;46:1175-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tsuda Y, Fujiwara T, Stevenson JD, Abudu A. Surgical outcomes of bone sarcoma of the foot. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2021;51:1541-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Leddy LR, Holmes RE. Chondrosarcoma of bone. Cancer Treat Res. 2014;162:117-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Soldatos T, McCarthy EF, Attar S, Carrino JA, Fayad LM. Imaging features of chondrosarcoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2011;35:504-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Herget GW, Uhl M, Opitz OG, Adler CP, Südkamp NP, Knöller S. The many faces of chondrosarcoma of bone, own cases and review of the literature with an emphasis on radiology, pathology and treatment. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2011;78:501-509. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Littrell LA, Wenger DE, Wold LE, Bertoni F, Unni KK, White LM, Kandel R, Sundaram M. Radiographic, CT, and MR imaging features of dedifferentiated chondrosarcomas: a retrospective review of 174 de novo cases. Radiographics. 2004;24:1397-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ollivier L, Vanel D, Leclère J. Imaging of chondrosarcomas. Cancer Imaging. 2003;4:36-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Anderson WJ, Doyle LA. Updates from the 2020 World Health Organization Classification of Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours. Histopathology. 2021;78:644-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gelderblom H, Hogendoorn PC, Dijkstra SD, van Rijswijk CS, Krol AD, Taminiau AH, Bovée JV. The clinical approach towards chondrosarcoma. Oncologist. 2008;13:320-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang HZ, Ding Y, Yang TT, Liu ZY, Jiang ZM. [Advances in molecular pathological diagnosis of bone tumors and changes in WHO classification in the 2020 edition]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:1221-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Evans HL, Ayala AG, Romsdahl MM. Prognostic factors in chondrosarcoma of bone: a clinicopathologic analysis with emphasis on histologic grading. Cancer. 1977;40:818-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Amary MF, Bacsi K, Maggiani F, Damato S, Halai D, Berisha F, Pollock R, O'Donnell P, Grigoriadis A, Diss T, Eskandarpour M, Presneau N, Hogendoorn PC, Futreal A, Tirabosco R, Flanagan AM. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol. 2011;224:334-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 703] [Cited by in RCA: 761] [Article Influence: 54.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pacifici M. Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: New Insights into Pathogenesis, Clinical Complications, and Potential Treatments. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2017;15:142-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ahmed AR, Tan TS, Unni KK, Collins MS, Wenger DE, Sim FH. Secondary chondrosarcoma in osteochondroma: report of 107 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;193-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lin PP, Moussallem CD, Deavers MT. Secondary chondrosarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:608-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bernard SA, Murphey MD, Flemming DJ, Kransdorf MJ. Improved differentiation of benign osteochondromas from secondary chondrosarcomas with standardized measurement of cartilage cap at CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 2010;255:857-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jurik AG. Multiple hereditary exostoses and enchondromatosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020;34:101505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cheng P, Chen K, Zhang S, Mu KT, Liang S, Zhang Y. IDH1 R132C and ERC2 L309I Mutations Contribute to the Development of Maffucci's Syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:763349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Verdegaal SH, Bovée JV, Pansuriya TC, Grimer RJ, Ozger H, Jutte PC, San Julian M, Biau DJ, van der Geest IC, Leithner A, Streitbürger A, Klenke FM, Gouin FG, Campanacci DA, Marec-Berard P, Hogendoorn PC, Brand R, Taminiau AH. Incidence, predictive factors, and prognosis of chondrosarcoma in patients with Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome: an international multicenter study of 161 patients. Oncologist. 2011;16:1771-1779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schwartz HS, Zimmerman NB, Simon MA, Wroble RR, Millar EA, Bonfiglio M. The malignant potential of enchondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:269-274. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Özmanevra R, Calikoglu E, Mocan G, Erler K. Grade 2 Chondrosarcoma of the Great Toe: An Unusual Location. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2019;109:393-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Roitman PD, Farfalli GL, Ayerza MA, Múscolo DL, Milano FE, Aponte-Tinao LA. Is Needle Biopsy Clinically Useful in Preoperative Grading of Central Chondrosarcoma of the Pelvis and Long Bones? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:808-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Andreou D, Ruppin S, Fehlberg S, Pink D, Werner M, Tunn PU. Survival and prognostic factors in chondrosarcoma: results in 115 patients with long-term follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:749-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Laitinen MK, Parry MC, Le Nail LR, Wigley CH, Stevenson JD, Jeys LM. Locally recurrent chondrosarcoma of the pelvis and limbs can only be controlled by wide local excision. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B:266-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bickels J, Campanacci DA. Local Adjuvant Substances Following Curettage of Bone Tumors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102:164-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mondal SK. Chondrosarcoma of the distal phalanx of the right great toe: report of a rare malignancy and review of literature. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:123-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Haliloglu N, Sahin G, Ekinci C. Periosteal chondrosarcoma of the foot: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:488.e1-488.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Masuda T, Otuka T, Yonezawa M, Kamiyama F, Shibata Y, Tada T, Matsui N. Chondrosarcoma of the distal phalanx of the second toe: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2004;43:110-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Rafi M, Abbas S, Intakhab B, Shehzad A, Sultan G, Ahmed S, Maqbool A, Mohsin R, Bhutto K, Mubarak M, Hashmi A, Rizvi AUH. Chondrosarcoma of right big toe with metastases to left orbital and left infra temporal region. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69:896-898. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Funovics PT, Panotopoulos J, Sabeti-Aschraf M, Abdolvahab F, Funovics JM, Lang S, Kotz RI, Dominkus M. Low-grade chondrosarcoma of bone: experiences from the Vienna Bone and Soft Tissue Tumour Registry. Int Orthop. 2011;35:1049-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lesenský J, Matejovsky ZJ, Vcelak J, Ostadal M, Hosova M, Bavelou C, Sioutis S, Bekos A, Mavrogenis AF. Chondrosarcomas of the small bones: analysis of 44 patients. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2021;31:1597-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Dierselhuis EF, Goulding KA, Stevens M, Jutte PC. Intralesional treatment versus wide resection for central low-grade chondrosarcoma of the long bones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD010778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fiorenza F, Abudu A, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Tillman RM, Ayoub K, Mangham DC, Davies AM. Risk factors for survival and local control in chondrosarcoma of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lechler P, Renkawitz T, Campean V, Balakrishnan S, Tingart M, Grifka J, Schaumburger J. The antiapoptotic gene survivin is highly expressed in human chondrosarcoma and promotes drug resistance in chondrosarcoma cells in vitro. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | de Jong Y, Ingola M, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Kruisselbrink AB, Venneker S, Palubeckaite I, Heijs BPAM, Cleton-Jansen AM, Haas RLM, Bovée JVMG. Radiotherapy resistance in chondrosarcoma cells; a possible correlation with alterations in cell cycle related genes. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2019;9:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Goda JS, Ferguson PC, O'Sullivan B, Catton CN, Griffin AM, Wunder JS, Bell RS, Kandel RA, Chung PW. High-risk extracranial chondrosarcoma: long-term results of surgery and radiation therapy. Cancer. 2011;117:2513-2519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |