Published online Aug 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8735

Peer-review started: March 21, 2022

First decision: May 30, 2022

Revised: June 11, 2022

Accepted: July 16, 2022

Article in press: July 16, 2022

Published online: August 26, 2022

Processing time: 147 Days and 22.5 Hours

A malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumor (MMNST), previously known as a melanotic schwannoma, is a rare variant of a peripheral nerve sheath tumor composed of Schwann cells with melanotic differentiation. Only a few reports of spinal MMNST have been reported.

In the first case, a 58-year-old woman presented with a history of low back pain and paresthesia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) of the lumbar spine revealed an intradural extramedullary mass lesion with amorphous linear calcification. Complete tumor resection was performed and histological examination revealed a psammomatous melanotic schwannoma. In the second case, a 72-year-old man presented with low back pain and paresthesia. MRI of the thoracolumbar spine revealed an intramedullary mass lesion at the T11 vertebral body level. The mass lesion was hypointense on T2WI and hyperintense on T1WI. Tumor resection was performed and the histologic result was melanotic schwannoma.

MMNST should be considered in the differential diagnosis when calcification or melanin is seen in an intradural spinal tumor.

Core Tip: Spinal malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumor (MMNST) are rare entities. We report two cases of spinal MMNSTs with or without psammomatous bodies. These cases highlight the importance of considering these rare entities when there are characteristic imaging findings such as the presence of intra-lesional T1-hyperintensity or calcification in intradural spinal tumors.

- Citation: Yeom JA, Song YS, Lee IS, Han IH, Choi KU. Malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumors in the spinal canal of psammomatous and non-psammomatous type: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(24): 8735-8741

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i24/8735.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8735

Melanotic schwannoma (MS) is a neoplasm of neuroectodermal origin characterized by melanotic pigmentation in the cytoplasm of Schwann cells[1]. MS is an extremely rare type of nerve sheath tumor, accounting for less than 1% of all primitive nerve sheath tumors[2]. MS was first described by Millar in 1932 as a malignant melanotic tumor of ganglion cells which was subsequently termed melanocytic schwannoma in 1975 by Folpe et al[3]. MS was previously classified as a benign tumor in the 2013 WHO classification, but in the 2020 WHO classification, the term “melanotic schwannoma” was revised to “malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumor (MMNST)” due to its malignant behavior[4]. MMNST is a rare aggressive peripheral nerve sheath tumor composed of Schwann cells with melanotic differentiation[5]. Spinal MMNST occurs in the lumbosacral (47.2%), thoracic (30.5%) and cervical (22.2%) regions[6]. Rarely, the intramedullary type is seen. MMNST can be divided into psammomatous (affecting spinal nerves and paraspinal ganglia) and non-psammomatous (affecting autonomic nerves of the viscera and cranial nerves) types[7]. The peak age of presentation is slightly younger (20–50 years) than that for conventional schwannomas[7]. Here, we present two cases of psammomatous and non-psammomatous MMNST that occurred in the spinal canal, focusing on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) images.

Case 1: A 58-year-old woman presented with a history of low back pain, paresthesia and cold sensation in both legs for several years.

Case 2: A 72-year-old man presented with a 6-mo history of low back pain and paresthesia in both legs.

Case 1: The symptoms were gradual in onset and progressive in nature leading to difficulty in walking. The patient felt abnormal sensations in both legs.

Case 2: The patient had a 6-mo history of low back pain and paresthesia in both legs and a 3-mo history of gait disturbance.

Case 1: The patient did not have any history of trauma or weight loss. She had no history of previous surgery or medications.

Case 2: There was no history of trauma, fever or weight loss. However, the patient had diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

Cases 1 and 2: These patients had no family history of malignancy.

Case 1: The patient had normal vital signs and there was no tenderness over the lumbar spine. There was no motor dysfunction in either leg.

Case 2: The motor function of the lower legs was grade 4 and anal tone was also decreased.

Case 1: Laboratory examinations were unremarkable including complete blood count, coagulation profile, C-reactive protein and serum electrolytes. Preoperative laboratory results were all normal.

Case 2: The total leukocyte percentage and leukocyte count were in the normal range and the test for rheumatic factor was negative. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels were also within the normal range.

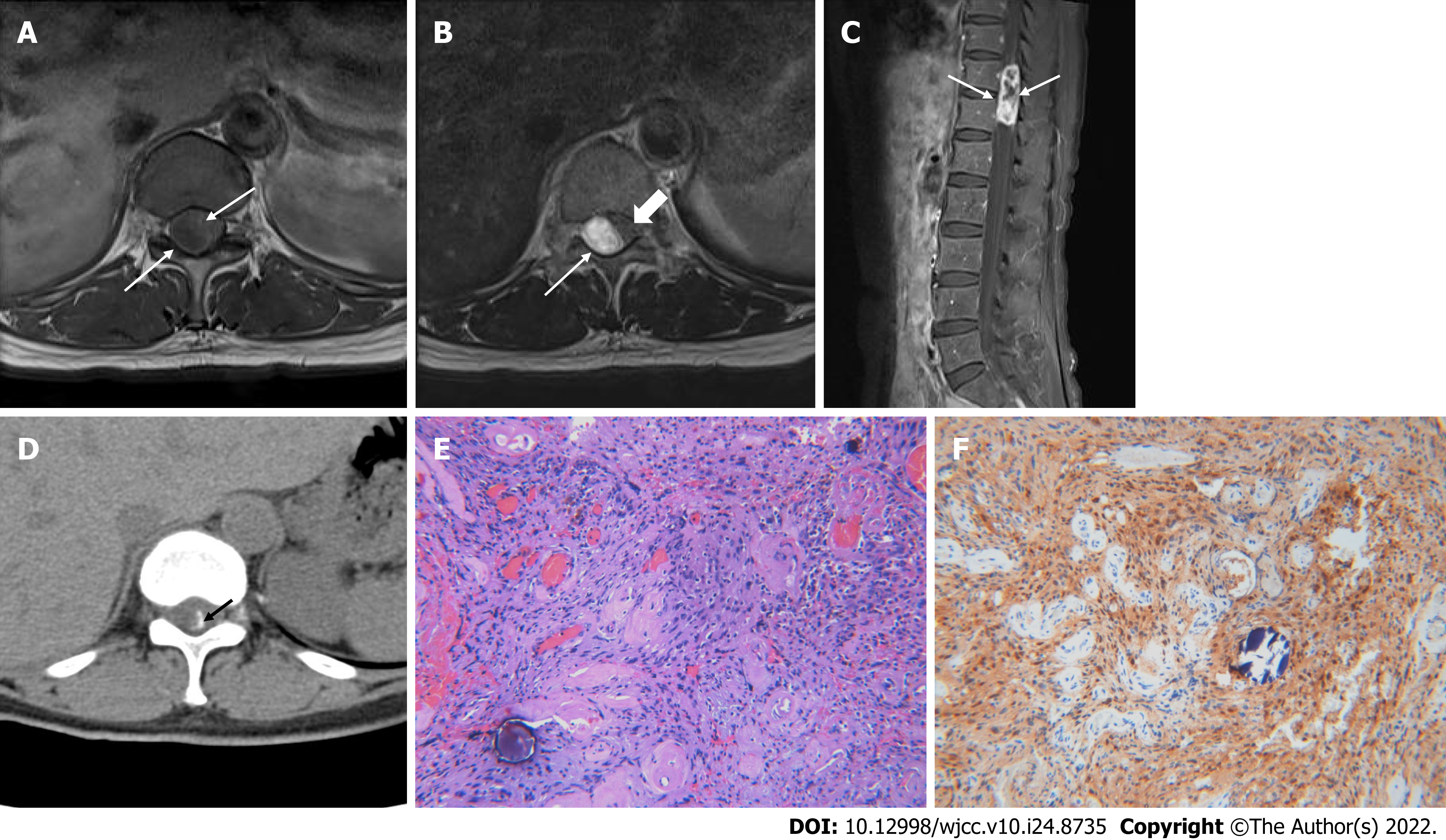

Case 1: There were no specific abnormal findings on plain radiographs of the thoracolumbar spine. MR imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed an intradural extramedullary mass lesion measuring 4.1 cm × 1.6 cm × 1.3 cm at the T11-12 Level with low signal intensity (SI) similar to that of the spinal cord on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) and heterogeneously high SI on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) (Figure 1A and B). The margins of the masses were well defined. The mass showed heterogeneous enhancement with no centrally enhancing portion on contrast-enhanced imaging (Figure 1C). There was spinal cord compression and displacement by the mass lesion causing compressive myelopathy of the above spinal cord. Amorphous linear calcification was observed in the peripheral margin of the mass lesion on a CT scan of the thoracolumbar spine (Figure 1D). Considering the location and imaging findings of the lesion, myxopapillary ependymoma and calcified meningioma were considered as differential diagnoses.

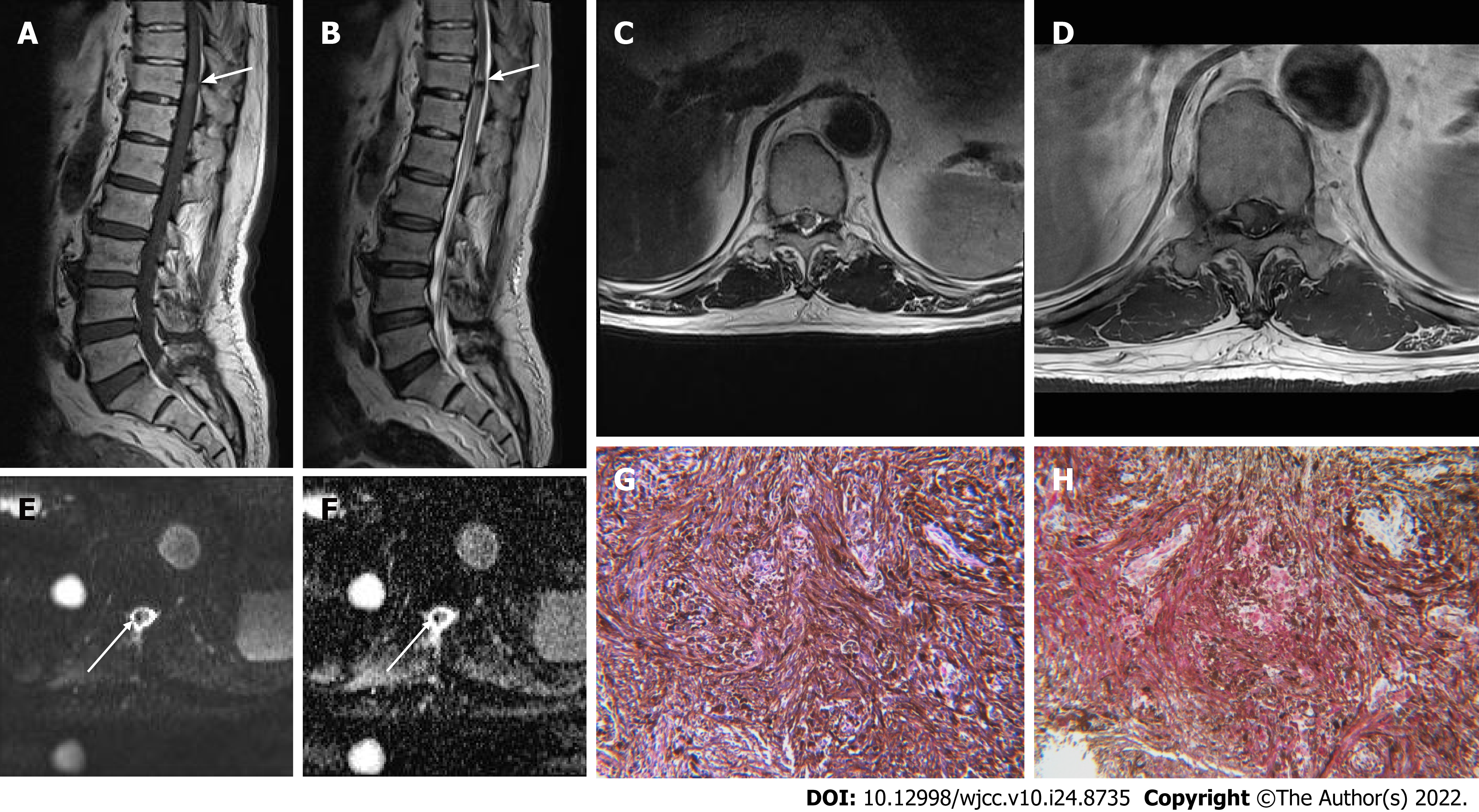

Case 2: Radiographs of the thoracolumbar spine showed findings indicative of ankylosing spondylitis. MRI of the thoracolumbar spine revealed an intramedullary mass lesion with a round shape and eccentric location measuring approximately 1 cm × 0.6 cm × 0.6 cm at the T11 vertebral body level. The mass lesion was hypointense on T2WI and hyperintense on T1WI (Figure 2A-C). Contrast-enhanced images demonstrated homogenous enhancement (Figure 2D). On DWI, the lesion showed a signal void. In the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map, the lesion did not show diffusion restriction (Figure 2E and F). The ADC value was 1.33 × 10-3 mm2/s. Melanoma and angioma were considered as differential diagnoses considering the characteristic signal intensity of the lesion.

Case 1: A laminectomy was performed at the T10-12 Level and complete tumor resection was performed under intra-operative neurophysiological monitoring. The tumor was dissected from the adherent surrounding spinal cord. On gross findings, fragments of brownish-white soft tissue were seen. Histological examination revealed epithelioid and spindle-shaped Schwann cells with brownish pigment and psammomatous bodies (Figure 1E). On immunohistochemistry, positive immunoactivity was shown for S-100 protein (Figure 1F) and vimentin. HMB45, Melan-A and GFAP were negative. The Ki67 proliferation index was 7.7%.

Case 2: A partial laminectomy was performed at the T11-T12 Level under intraoperative neurophy

Case 1: The final diagnosis was psammomatous melanotic schwannoma.

Case 2: These findings are compatible with melanotic schwannoma.

Case 1: Since the patient underwent complete tumor resection for the diagnosis, the patient did not receive any further treatment except for the subsequent imaging follow-up.

Case 2: The adhesion between the mass and spinal cord was severe and bleeding was severe so only a biopsy was performed. Total removal of the mass was not performed.

Case 1: After the surgery, the preoperative symptoms including low back pain and paresthesia in both lower legs were all improved. The patient declined follow-up MRI; however, no special symptoms or signs have since developed.

Case 2: The lesion was followed up three times on MRI once a year after surgery. The size and imaging characteristics of the lesion did not change significantly. Also, an annual chest and abdominal CT exam revealed that there was no evidence of distant metastasis through the follow-up period.

A MMNST is composed of Schwann cells capable of melanogenesis[1]. It usually arises in association with spinal or visceral autonomic nerves[5]. Approximately 50% of cases are associated with the Carney complex[7]. Psammomatous MMNSTs account for approximately half of all MMNSTs, and approximately half of these are associated with the Carney complex[8]. Thus, in cases of an MMNST, it is necessary to search for clinicopathologic components of the Carney complex[9]. The Carney complex is characterized by autosomal dominant inheritance as well as familial multitumoral syndrome, comprising myxomas (cardiac, cutaneous and mammary), spotty pigmentation and endocrine overactivity (Cushing's syndrome and acromegaly)[2]. However, in our case, neither patient had clinical or physical findings or a family history of the Carney complex.

Solomou et al[10] reviewed 65 reported cases of extramedullary spinal melanotic schwannoma and these tumors most commonly occurred between 30 years and 40 years of age. But in our two cases, it was diagnosed at a much older age. MMNST patients usually have symptoms due to compression of adjacent structures during the fourth decade. A previous literature review revealed that more than 50% of cases have local recurrence or distant metastasis or both[10]. However, in the present cases, malignant changes, local recurrence and metastases were not detected. There are no known diagnostic radiological characteristics for MMNSTs; therefore, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish them from other melanin-containing tumors. On CT, a psammomatous MMNST can appear as a dense mass with calcification. In this situation, calcified meningioma, which is common in this location, should be included in the differential diagnosis. On MRI, MS of the spine is usually located along the spinal nerve root and sometimes in the form of a dumbbell[11]. Since our cases were located in the intradural space, the dumbbell shape was not visible. MMNSTs rarely occur within the spinal cord. In our second case, the mass lesion had an eccentric position within the spinal cord.

The presence of paramagnetic free radicals in melanin produces characteristic T1 hyperintensity and T2 hypointensity in tumors, providing important clues regarding the more specific properties of what might appear as a typical neuron-enveloping tumor. This T1 hyperintensity is a hallmark of melanin, but subacute bleeding can also explain these findings, and it can be difficult to distinguish them from hemorrhagic lesions such as spongy malformations[12]. Melanin-containing lesions, including malignant melanoma, melanoma, pigmented neurofibroma, perineural melanoma and metastatic melanoma are another reason for T1 shortening[7]. The signal intensity of the lesion may be variable due to the concentration of melanin[13]. They usually show enhancement with contrast.

Although complete resection is sufficient to treat sporadic and psammomatous types of MMNST, malignant deformation and recurrence of the tumor should always be kept in mind and subsequent imaging of the patient should continue for at least 5 years[14]. In case 1, complete excision of the mass was possible; but in case 2, the adhesion between the mass and spinal cord was severe so only a biopsy was performed. No imaging features enable differentiation between MMNST and conventional schwannomas. In addition, the differentiation between intradurally-located melanotic tumors and other intradural tumors in the spine is difficult. The differential diagnosis of MMNSTs of apparent nerve sheath origin includes leptomeningeal melanocytoma, ancient schwannoma, pigmented neurofibroma, biphasic synovial sarcoma, neurilemmoma and melanoma[7].

Case 1 was characterized by the location of the mass near the conus medullaris and calcification at the peripheral rim of the mass. Thus, calcified meningioma and myxopapillary ependymoma were included in the differential diagnosis. Although previous reports revealed various locations of spinal MMNSTs[10], we didn’t consider an MMNST with a psammomatous body as a differential diagnosis. Punctate calcification foci are frequently found in spinal meningiomas due to the psammoma bodies[15]. Also, conventional schwannomas usually demonstrate a higher signal intensity on T2WI, cystic changes and inhomogeneous enhancement. In our case, the tumor showed T1 hyperintensity and T2 hypointensity so we didn’t consider the possibility of these rare variants of nerve sheath tumor. Although the MR findings in myxopapillary ependymomas were nonspecific, the diagnosis can be suggested by a large, intensely enhancing, intradural extramedullary thoracolumbar mass that extends for several vertebral levels[16]. Intradural extramedullary lesions in the region of the conus medullaris include myxopapillary ependymoma, paraganglioma, nerve sheath tumor, meningioma and metastasis[16]. Due to the older age and uncommon location (conus medullaris) compared to previous reports[10], the correct diagnosis was difficult in case 1.

In case 2, the high signal intensity on T1WI and low signal intensity on T2WI of the mass were characteristic. Thus, melanoma and angioma were included in the differential diagnosis. The majority of spinal melanomas are frequently observed in the middle or lower thoracic spinal cord. Liu et al[17] showed a pattern of spinal melanoma on MRI which includes hyperintensity on T1WI and iso- or hypointensity on T2WI. Compared to melanotic schwannoma, spinal melanoma contains more concentration of melanin[10]. Melanoma does not always show a homogeneous pattern on MRI[18]. The MRI signal of melanocytic tumors depends on the presence of melanin, acute or chronic intratumoral hemorrhages and fat deposits. On the other hand, cavernous angiomas exhibit a dark rim on T2WI due to hemosiderin deposition[19]. Small size, eccentric axial location, minimal enhancement and absence of edema are significant MR findings of cavernous angioma[19]. In addition, longitudinal spreading of hemorrhage may be observed on serial follow-up images of spinal cavernous angiomas[19]. Considering previous reports, case 2 shows relatively characteristic findings of an MMNST, but older age and the rarity of this disease entity made the correct diagnosis difficult. However, unlike in case 1, the patient in case 2 undertook diffusion-weighted images. Most hypercellular malignant tumors show diffusion restriction, but our case did not show any diffusion restriction. Considering the malignant behavior of this rare disease, future studies could focus on functional images that could predict recurrence or metastasis of this disease.

In conclusion, we report on two cases of melanotic schwannoma located in the intradural space of the spine. The two MMNSTs reported here had rare intradural locations and showed various characteristics of relatively common tumors that could have an intradural location such as meningioma, schwannoma, melanoma and angioma. They also developed at an older age than in the cases previously reported in the literature. When calcification is seen in a mass, MMNST, as well as meningioma, should be considered among psammomatous type tumors in the differential diagnosis. Moreover, when the mass exhibits a characteristic signal intensity suggesting melanin-like T1 hyperintensity with T2 hypointensity, MMNST may be included in the differential diagnosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu C, China; Wang G, China S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Bird CC, Willis RA. The histogenesis of pigmented neurofibromas. J Pathol. 1969;97:631-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alexiev BA, Chou PM, Jennings LJ. Pathology of Melanotic Schwannoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1517-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fu YS, Kaye GI, Lattes R. Primary malignant melanocytic tumors of the sympathetic ganglia, with an ultrastructural study of one. Cancer. 1975;36:2029-2041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Choi JH, Ro JY. The 2020 WHO Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue: Selected Changes and New Entities. Adv Anat Pathol. 2021;28:44-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 62.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Folpe AL, Hameed M. The WHO Classification of tumours editorial board. Malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumour. WHO Classification of tumours soft tissue and bone tumours, 5th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2020:258-260. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Keskin E, Ekmekci S, Oztekin O, Diniz G. Melanotic Schwannomas Are Rarely Seen Pigmented Tumors with Unpredictable Prognosis and Challenging Diagnosis. Case Rep Pathol. 2017;2017:1807879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Carney JA. Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma. A distinctive, heritable tumor with special associations, including cardiac myxoma and the Cushing syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:206-222. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Shields LB, Glassman SD, Raque GH, Shields CB. Malignant psammomatous melanotic schwannoma of the spine: A component of Carney complex. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Peltier J, Page C, Toussaint P, Bruniau A, Desenclos C, Le Gars D. Melanocytic schwannomas. Report of three cases. Neurochirurgie. 2005;51:183-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Solomou G, Dulanka Silva AH, Wong A, Pohl U, Tzerakis N. Extramedullary malignant melanotic schwannoma of the spine: Case report and an up to date systematic review of the literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;59:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Marton E, Feletti A, Orvieto E, Longatti P. Dumbbell-shaped C-2 psammomatous melanotic malignant schwannoma. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:591-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Höllinger P, Godoy N, Sturzenegger M. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in isolated spinal psammomatous melanotic schwannoma. J Neurol. 1999;246:1100-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liessi G, Barbazza R, Sartori F, Sabbadin P, Scapinello A. CT and MR imaging of melanocytic schwannomas; report of three cases. Eur J Radiol. 1990;11:138-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goasguen O, Boucher E, Pouit B, Soulard R, Le Charpentier M, Pernot P. [Melanotic schwannoma, a tumor with a unpredictable prognosis: case report and review of the literature]. Neurochirurgie. 2003;49:31-38. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Lee JW, Lee IS, Choi KU, Lee YH, Yi JH, Song JW, Suh KJ, Kim HJ. CT and MRI findings of calcified spinal meningiomas: correlation with pathological findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39:345-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wippold FJ 2nd, Smirniotopoulos JG, Moran CJ, Suojanen JN, Vollmer DG. MR imaging of myxopapillary ependymoma: findings and value to determine extent of tumor and its relation to intraspinal structures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1263-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liu QY, Liu AM, Li HG, Guan YB. Primary spinal melanoma of extramedullary origin: a report of three cases and systematic review of the literature. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2015;1:15003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sun L, Song Y, Gong Q. Easily misdiagnosed delayed metastatic intraspinal extradural melanoma of the lumbar spine: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1799-1802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jeon I, Jung WS, Suh SH, Chung TS, Cho YE, Ahn SJ. MR imaging features that distinguish spinal cavernous angioma from hemorrhagic ependymoma and serial MRI changes in cavernous angioma. J Neurooncol. 2016;130:229-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |