Published online Aug 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8673

Peer-review started: February 12, 2022

First decision: May 30, 2022

Revised: June 13, 2022

Accepted: July 22, 2022

Article in press: July 22, 2022

Published online: August 26, 2022

Processing time: 184 Days and 16.2 Hours

DeBakey type I aortic dissection is one of the rare etiologies of ischemic stroke. It is critical to identify arterial dissection before intravenous thrombolysis; otherwise, fatal hemorrhage may occur.

In this report, we described 2 painless DeBakey type I aortic dissection cases with initial symptoms similar to ischemic stroke. Sudden onset of conscious disturbance and limb weakness within minutes occurred in both cases. Hypotension was found in both cases. Thoracoabdominal computed tomography angiography was urgently performed due to unknown reason hypotension, and DeBakey type I aortic dissection was confirmed. Intravenous thrombolysis was avoided because of timely diagnosis; however, they both eventually died of ruptured aortic dissection.

Aortic dissection should always be excluded in ischemic stroke patients with unexplained hypotension or shock symptoms before intravenous thrombolytic therapy.

Core Tip: Aortic dissection should always be excluded in ischemic patients with unexplained hypotension or shock symptoms before intravenous thrombolytic therapy. These two painless DeBakey Type I aortic dissection cases with initial symptoms similar to ischemic stroke intravenous thrombolysis was avoided because of timely diagnosis.

- Citation: Chen SQ, Luo WL, Liu W, Wang LZ. Beware of the DeBakey type I aortic dissection hidden by ischemic stroke: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(24): 8673-8678

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i24/8673.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8673

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is the leading cause of death and disability in the world. It is defined as the sudden loss of blood flow to an area of the brain, resulting in a corresponding loss of neurologic function. In order to rescue more penumbra tissue, vascular recanalization treatment, such as intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular clot retrieval, should be carried out as soon as possible because the recanalization time is directly related to the outcomes[1]. Although intravenous thrombolysis is widely used, carefully excluding patients with contraindications of thrombolytic therapy is critical. Aortic dissection is the absolute contraindication of thrombolytic therapy, and it is an uncommon, life-threatening cause of ischemic stroke. Typical aortic dissection presents with tearing chest or back pain, but painless aortic dissection with only focal neurological deficits can be a challenge for emergency physicians, and inadvertently treating this situation with thrombolytic agents may threaten the patient's life.

In this report, we describe 2 painless DeBakey type I aortic dissection patients presenting initial symptoms similar to ischemic stroke who were eligible for thrombolytic treatment. We report these cases with the aim to emphasize the importance of ruling out aortic dissection before fibrinolytic treatment in AIS patients.

Case 1: A 73-year-old Chinese man was brought to the emergency room by the family with the complaint of sudden onset of altered consciousness and right-limb weakness for 1 h.

Case 2: A 68-year-old male suddenly lost consciousness one and half hour ago while standing up from the squat position.

Case 1: Symptoms of right-limb weakness, altered consciousness, and urinary/bowel incontinence occurred within ten seconds to minutes observed by the family 1 h ago while he was cooking. No nausea or vomiting was observed during the clinical course.

Case 2: Symptoms occurred concurrent with the postural change. After arriving at the emergency room, the patient became conscious and complained of neither chest or back pain, nor nausea or vomiting. He presented with slight dysarthria and slow response.

Case 1: The patient had intermittent gout attacks for 3 years.

Case 2: The patient was diagnosed with "cerebral infarction" 21 years ago for the sudden onset of left limb weakness. He underwent decompressive craniectomy for “cerebral hemorrhage” 19 years ago. He had "subarachnoid hemorrhage" 12 years ago and recovered after conservative treatment. The patient was independent for daily activities and could walk upstairs and downstairs without issues before this attack.

Case 1: The family denied any family history of similar medical conditions or genetic disease.

Case 2: He had a drinking history of more than 30 years but had quit drinking for more than 10 years. He smoked for more than 30 years but quit smoking 10 years ago. The patient denied any family history of similar medical conditions or genetic disease.

Case 1: On physical examination, the patient had a pale face and wet and cold limbs. The vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 36.8 ℃; blood pressure (BP), 98/58 mmHg (right arm), 101/60 mmHg (left arm); heart rate, 56 beats per min; respiratory rate, 22 breaths per min. There was no murmur in the heart valve auscultation area. Nervous system condition: Blurred consciousness with Glasgow Coma Scale of 10 point, passive posture, Broca’s aphasia, grade II muscle strength of the right limb, normal muscle strength of the left limb, and positive Babinski sign of right lower limb.

Case 2: Low BP (84/68 mmHg) was detected at the emergency room, but was found to be normal at the neurology department. The vital signs at neurology department were as follows: Body temperature 36.0 ℃; BP, 121/74 mmHg (right arm); 110/60 mmHg (left arm); heart rate 89 beats per min; respiratory rate 15 breaths per min. Furthermore, the patient had obvious cyanosis. The muscle strength of the four limbs had decreased slightly with grading V-.

Case 1: Complete blood count was normal. Blood biochemistry indicates renal insufficiency (creatinine, 201 μmol/L; urea nitrogen, 11 mmol/L). D-dimer was more than 16 μg/mL.

Case 2: D-dimer was elevated (1.9 μg/mL). Blood gas analysis indicated low blood oxygen (pressure of O2, 9.47 kPa). Complete blood count was normal.

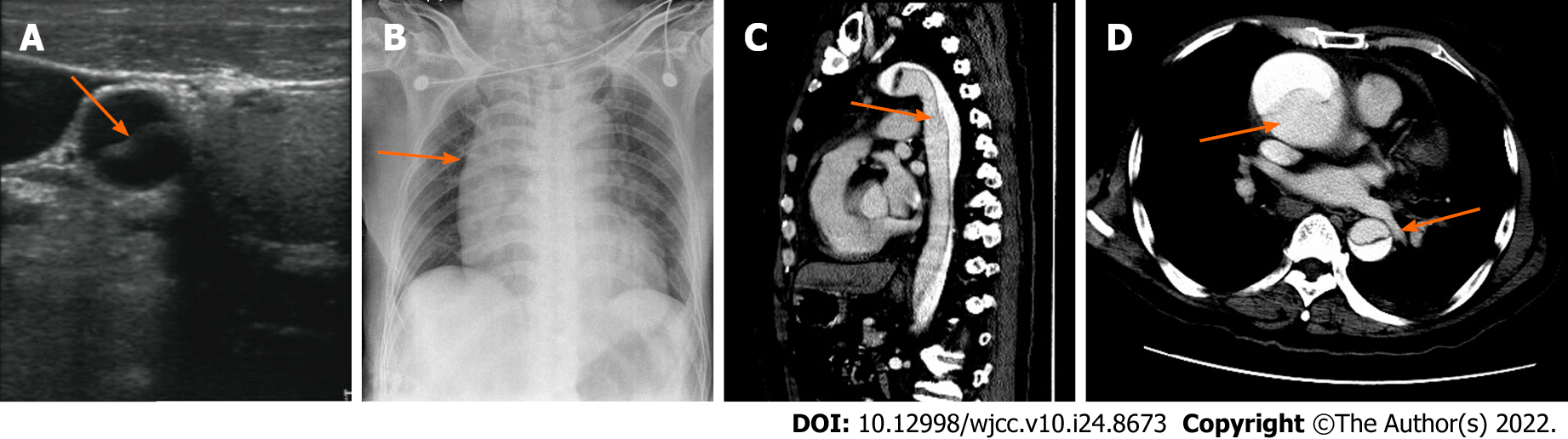

Case 1: Computed tomography (CT) of the brain did not find any low-density focus, which indicated that the patient was eligible for thrombolytic treatment. Doppler ultrasound of the carotid artery was applied in an attempt to determine the possible cause of the unexplained hypotension, and it found both right common carotid and right internal carotid artery dissection (Figure 1A). Bedside chest X-ray indicated widening of the right mediastinum (Figure 1B). Therefore, thoracic and abdominal CT angiography (CTA) was urgently performed, and DeBakey type I aortic dissection was confirmed (Figure 1C and D).

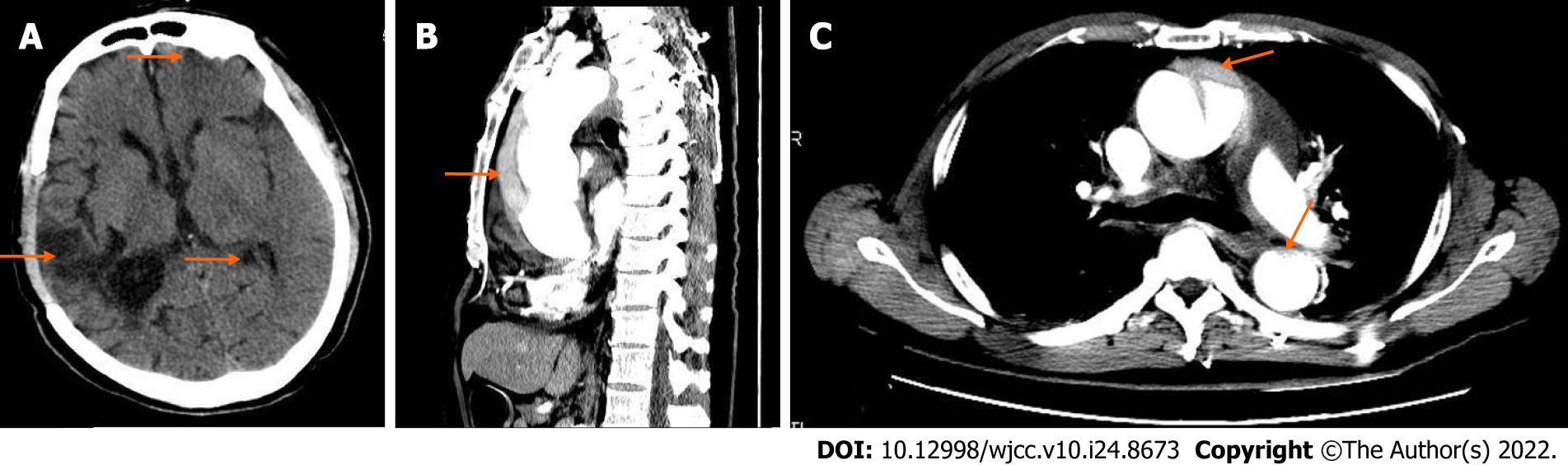

Case 2: The chest X-ray did not reveal mediastinum widening. A cranial CT scan showed multiple chronic brain infarctions (Figure 2A). Considering the high risk of bleeding in this patient, the family refused intravenous thrombolysis. Due to unexplained cyanosis and sweating limbs, a thoracoabdominal CT scan was performed in an attempt to determine the underlying causes. The CTA enabled a definite diagnosis of DeBakey type I aortic dissection (Figure 2B and C).

Case 1: Combined with the patient’s clinical history and imaging findings, the final diagnosis was DeBakey type I aortic dissection complicated with cerebral infarction. Chronic renal insufficiency was the secondary diagnosis.

Case 2: Combined with the patient’s clinical history and imaging findings, the final diagnosis was DeBakey Type I aortic dissection complicated with cerebral infarction. Chronic cerebral infarction was the secondary diagnosis.

Case 1: Since our hospital was unable to perform the open surgery to repair the damaged aorta, we recommended the patient be transferred to another hospital. Carefully monitoring vital signs, controlling BP, and avoiding excessive exertion were implemented before referral.

Case 2: We carefully monitored the patient’s vital signs, controlled BP, and gave appropriate sedation. We suggested the patient be transferred to another hospital for surgical treatment.

Case 1: On the 2nd day of admission, the patient suddenly died due to rupture of the arterial dissection before the transfer.

Case 2: The patient died 10 h after admission when his family members were discussing whether to transfer him to a different hospital for surgical treatment.

Acute aortic dissection (AAD) is characterized by the rapid development of an intimal flap. This is caused by blood flowing into the media and forcing the intima and the adventitia apart, which leads to life-threatening complications and death, particularly when the ascending aorta is involved[2]. According to the location of the dissection and/or origin of the intimal tear and the extent of the dissection, AAD can be classified into Stanford type A (or DeBakey type I and type II) and Stanford type B (or DeBakey type IIIa and type IIIb). Stanford type A aortic dissections involve the ascending aorta and usually require swift, open surgical repair, whereas Stanford type B dissections involve the descending but not the ascending aorta and are conventionally treated by endovascular repair and/or medical therapy[2]. AAD is an uncommon but life-threatening disease with a reported incidence of 3–5 cases per 100000 people per year[3], a figure which may rise to even as high as 35 cases per 100000 people per year at the age of 65-75-years-old[4]. About 20% of the untreated patients with DeBakey type I aortic dissection died immediately, whilst a further 1%-2% of the survivors died with every hour of delayed treatment[5].

Stroke is one of the most serious complications of DeBakey type I AAD, and the incidence of DeBakey type I arterial dissection complicated with stroke is about 6%[6] to 10%[7]. Arterial dissection represents 5.7% of first-ever ischemic strokes of unusual cause in a clinical series[8]. Arterial dissection presented with stroke symptoms and without typical chest or back pain can lead to a delayed diagnosis of dissection and that can significantly increase the mortality. Furthermore, thrombolysis treatment can result in 3-5 fold higher probability of fatalities than non-thrombolysis treatment of patients[9]. Therefore, urgently identifying the presence of arterial dissection in stroke patients is critical.

While aortic dissection can involve both of the carotid arteries, right hemisphere involvement is more commonly seen in previous reports[7]. The frequency of chest/back pain is much lower in AAD patients combined with stroke than those without stroke[7]. Altered consciousness, which may be either due to the sudden drop of BP after arterial dissection or damage of the brain, can lead to delayed reporting of chest/back pain. SBP difference greater than 20 mmHg between the two upper limbs is one of the characteristics of AAD, but in our case series, none of them had such manifestations. Furthermore, pulse deficits are present in about 20%–30% of ADD cases which emphasizes the importance of serial physical examinations that can substantially contribute to the correct diagnosis. Transient or persistent low BP or shock symptoms should always be taken seriously in ischemic stroke patients because most ischemic stroke patients usually have higher BP[7].

D-dimer is an important predictive value in the diagnosis of AAD, and D-dimer values less than 0.5 μg/mL can be used to rule out AAD[10]. However, D-dimer elevation is also common in acute stroke, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, particularly in cardioembolism[11]. D-dimer elevation has poor specificity in the diagnosis of aortic dissection, but is helpful to exclude aortic dissection when D-dimer is negative.

The contrast-enhanced CT scan is a reliable method for the definite diagnosis of AAD. In addition to enhanced CT scan, other auxiliary examinations, such as carotid ultrasound and chest X-ray, can also provide reference values for AAD diagnosis. Chest X-ray can be considered as part of the acute screening protocols in AIS patients with special enlarged mediastinal shadow in AAD. A common or internal carotid artery dissection can easily be investigated by ultrasonography, which can be regarded as a helpful, complementary tool for the current diagnostic workup[12].

Arterial dissection is a life-threatening emergency which needs urgent surgery or endovascular intervention. It is highly recommended to keep the SBP < 120 mmHg with intravenous β-blockers or vasodilators and careful management of any conditions that can increase thoraco-abdominal pressure is required to prevent the complication of aortic rupture prior to surgery or endovascular intervention.

In conclusion, when AIS patients developed a rapid peak of neurological symptoms, unexplained hypotension, or shock symptoms, arterial dissection as a differential diagnosis should always be excluded before intravenous thrombolysis. Serial monitoring, such as checking the differences in SBP between the two arms and peripheral arterial pulsation are important for diagnosis of arterial dissection. An abnormal carotid ultrasound finding and mediastinal widening on chest radiograph may also be helpful in identifying AAD. The elevation of D-dimer has no specificity value in diagnosing arterial dissection, but its negative value has high specificity in excluding AAD. For AIS patients who are suspected of arterial dissection, enhanced CTA examination is needed urgently to confirmed the diagnosis. To avoid arterial rupture, close monitoring of vital signs, ensuring proper bed rest, and the treatment of coughing and constipation are very important.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arboix A, Spain; Darbari A, India; Ueda H, Japan S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Fonarow GC, Zhao X, Smith EE, Saver JL, Reeves MJ, Bhatt DL, Xian Y, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Schwamm LH. Door-to-needle times for tissue plasminogen activator administration and clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke before and after a quality improvement initiative. JAMA. 2014;311:1632-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nienaber CA, Clough RE, Sakalihasan N, Suzuki T, Gibbs R, Mussa F, Jenkins MP, Thompson MM, Evangelista A, Yeh JS, Cheshire N, Rosendahl U, Pepper J. Aortic dissection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Olsson C, Thelin S, Ståhle E, Ekbom A, Granath F. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: increasing prevalence and improved outcomes reported in a nationwide population-based study of more than 14,000 cases from 1987 to 2002. Circulation. 2006;114:2611-2618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 562] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Howard DP, Banerjee A, Fairhead JF, Perkins J, Silver LE, Rothwell PM; Oxford Vascular Study. Population-based study of incidence and outcome of acute aortic dissection and premorbid risk factor control: 10-year results from the Oxford Vascular Study. Circulation. 2013;127:2031-2037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 388] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 49.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Orihashi K. Acute type a aortic dissection: for further improvement of outcomes. Ann Vasc Dis. 2012;5:310-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gaul C, Dietrich W, Friedrich I, Sirch J, Erbguth FJ. Neurological symptoms in type A aortic dissections. Stroke. 2007;38:292-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ohara T, Koga M, Tokuda N, Tanaka E, Yokoyama H, Minatoya K, Nagatsuka K, Toyoda K, Minematsu K. Rapid Identification of Type A Aortic Dissection as a Cause of Acute Ischemic Stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:1901-1906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arboix A, Bechich S, Oliveres M, García-Eroles L, Massons J, Targa C. Ischemic stroke of unusual cause: clinical features, etiology and outcome. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hong KS, Park SY, Whang SI, Seo SY, Lee DH, Kim HJ, Cho JY, Cho YJ, Jang WI, Kim CY. Intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator thrombolysis in a patient with acute ischemic stroke secondary to aortic dissection. J Clin Neurol. 2009;5:49-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shimony A, Filion KB, Mottillo S, Dourian T, Eisenberg MJ. Meta-analysis of usefulness of d-dimer to diagnose acute aortic dissection. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1227-1234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ageno W, Finazzi S, Steidl L, Biotti MG, Mera V, Melzi D'Eril G, Venco A. Plasma measurement of D-dimer levels for the early diagnosis of ischemic stroke subtypes. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2589-2593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Morelli N, Rota E, Mancuso M, Immovilli P, Spallazzi M, Rocca G, Michieletti E, Guidetti D. Carotid ultrasound imaging in a patient with acute ischemic stroke and aortic dissection: a lesson for the management of ischemic stroke? Int J Stroke. 2013;8:E53-E54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |