Published online Aug 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8625

Peer-review started: March 14, 2022

First decision: May 30, 2022

Revised: June 9, 2022

Accepted: July 20, 2022

Article in press: July 20, 2022

Published online: August 26, 2022

Processing time: 154 Days and 17.2 Hours

There are very few studies on the differential diagnosis between egocentric neglect (EN) and allocentric neglect (AN).

To investigate the overall trend of the previously developed assessment tools by conducting a descriptive review of the studies on assessment tools that can perform a differential diagnosis of EN and AN.

The data were collected by using databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, and ScienceDirect. The most commonly used search terms were “neglect”, “stroke”, “egocentric neglect”, and “allocentric neglect”.

A total of seven studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected and analyzed. We were able to confirm the research process, test method, and differential diagnosis criteria of the seven presented assessment tools from four studies on paper-based tests and three studies on computerized tests. The majority of the tests were carried out via the cancellation method using stimuli such as everyday objects or numbers. EN distinguished the left from right based on the test paper, while AN distinguished the left from right based on stimuli. In order to perform differential diagnosis, the difference in the number of left and right responses or non-responses was used based on the EN and AN criteria.

It was confirmed that all the seven assessment tools can effectively perform differential diagnosis of EN and AN. This study may provide important data that can be used in clinical practice for differential diagnosis and future intervention planning for neglect patients.

Core Tip: The purpose of this study was to investigate the overall trend of the previously developed assessment tools by conducting a descriptive review of the studies on assessment tools that can perform a differential diagnosis of egocentric neglect (EN) and allocentric neglect (AN). It was confirmed that all the seven assessment tools can effectively perform differential diagnosis of EN and AN. This study may provide important data that can be used in clinical practice for differential diagnosis and future intervention planning for neglect patients.

- Citation: Lee SH, Lim BC, Jeong CY, Kim JH, Jang WH. Assessment tools for differential diagnosis of neglect: Focusing on egocentric neglect and allocentric neglect. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(24): 8625-8633

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i24/8625.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8625

Neglect is a neurological deficit due to brain damage resulting in difficulty identifying information input from the opposite direction[1,2]. It is the most frequent serious sequelae following right hemisphere damage[3]. The main symptom of brain damage is difficulty in recognizing objects or people in the opposite space despite having adequate sensorimotor ability[4]. These symptoms make it difficult for a person to use their eyes, arms, and legs to search within a neglected space[5]. They also require assistance for independent daily life due to risk of secondary accidents including falls[6]. Neglect is classified into sensory neglect and motor neglect based on deficit type, and personal neglect, peri-personal neglect, and extra-personal neglect based on the distance of occurrence[7]. Due to various symptoms, neglect causes delays in rehabilitation treatment and recovery[8].

In 2001, Ota et al[9] conducted a study for the development of an assessment tool that can differentiate between two new types of neglect symptoms. The first type of neglect is egocentric neglect (EN), which focuses on an individual and neglects information in the opposite side of the brain damage. The second type of neglect is allocentric neglect (AN), which neglects information in the opposite side of the brain damage, regardless of the object’s location[9,10]. EN is also known as viewer-centered neglect, whereas AN is known as stimulus-centered neglect[11]. The research of Ota et al[9] led to the development of the apples test and the broken hearts test for better differentiation of the two types of neglect[12,13].

A study that measured language, memory, number, praxis, extinction, and controlled attention confirmed the difference between EN and AN symptoms. EN patients showed a lower performance in the memory domain, while AN patients showed a lower performance in all other domains[12]. AN also has a more adverse effect on daily life performance than EN[14], and AN patients recover at a slower and more difficult rate than that of the EN patients[15]. A new treatment method is deemed necessary as the existing neglect treatment has no effect on AN[16].

Differentiation is important for accurate diagnosis and confirmation of various symptoms in patients with neglect. This is essential for establishing an effective intervention[7,17]. Studies have been conducted to systematically review treatments, effects, and assessment tools for neglect[5,18-22], but none have examined the assessment tools that can effectively differentiate between EN and AN.

The purpose of this study was to review the assessment tools that can differentiate between EN and AN, and investigate the overall trend of the Ota test and newly developed assessment tools by analyzing various studies.

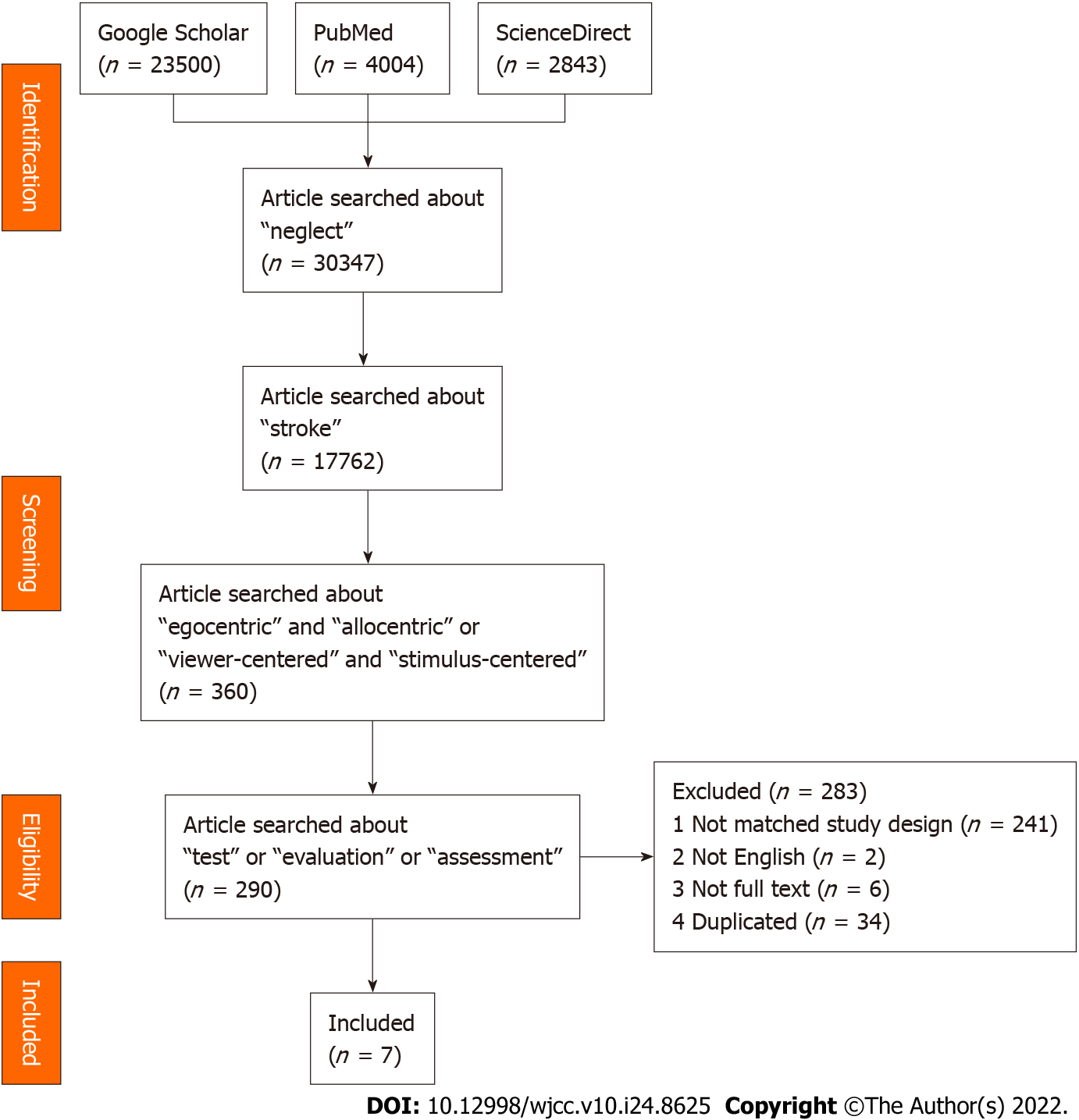

Data based on the articles on assessment tools that can differentiate between EN and AN were collected for this study by using databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, and ScienceDirect. The search keywords used were “neglect”, “stroke”, “egocentric neglect”, “allocentric neglect”, “viewer-centered neglect”, “stimulus-centered neglect”, “test”, “evaluation”, and “assessment”. The article search yielded 290 articles, among which seven were selected, excluding duplicated studies that met the exclusion criteria (Figure 1 and Table 1). In addition, we conducted a relevant search by Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/) and cited high-quality references.

| Name of assessment | Ref. | Type of participants | Type of assessment | Cut-off score | Time limit | Outcomes |

| Ota test | Ota et al[9], 2001 | n = 2. Stroke patients (only RBD) | Pencil and paper | EN: The number of omitted complete targets; AN: The number of selected incomplete targets | No limit | The test is developed in order to distinguish EN and AN with one task |

| Apples test | Bickerton et al[12], 2011 | n = 111. Experimental group: 25 (stroke patients-LBD: 7, RBD: 18); Control group: 86 (healthy participants) | Pencil and paper | Left EN: > 2; Right EN: < -2; Left AN: > 1; Right AN: < -1 | 5 min | The test provides a clinically applicable measure of different forms of neglect (EN and AN) |

| Broken hearts test | Demeyere et al[13], 2015 | n = 348. Experimental group: 208 (acute stroke patients-LBD: 84, RBD: 101, Both: 19, Unknown: 4); Control group: 140 (healthy participants) | Pencil and paper | Left EN: > 3; Right EN: < -3; Left AN: > 1; Right AN: < -1 | 3 min | The test presented the validity and applicability of the OCS in acute stroke assessment |

| Computerised cancellation test | Mizuno et al[24], 2015 | n = 19. Experimental group: 3 (stroke patients-only RBD, AND has neglect: 2, AND without neglect: 1); Control group: 16 (healthy participants) | Digital test (touchscreen) | EN: The number of omitted complete targets; AN: The number of selected incomplete targets (Ota test only) | No mention | The test is developed a computer-based programme to evaluate EN and AN |

| MonAmour robot test | Montedoro et al[25], 2019 | n = 91. Experimental group: 35 (stroke patients-LBD: 12, RBD: 23, AND has EN: 25, AND without EN: 10; Control group: 56 (healthy participants) | Digital test(Robot) | Left EN: ≥ 1Right EN: ≤ -1Left AN: ≥ 1Right AN: ≤ -1 | 7 s (each trial) | The test is a valid, sensitive, and reliable tool that can diagnose EN and AN |

| 3s spreadsheet test v2 | Chen et al[23], 2021 | n = 209. Experimental group: 23 (stroke patients, only RBD); Control group: 186 (healthy participants) | Pencil and paper test | Left EN: > 3; Right EN: < -3; Left AN: > 5; Right AN: < -3 | No limit (mean ± SD): 202.0 ± 64.6 s | The test may increase the comprehensiveness of the neglect assessment |

| ReMoVES platform | Ferraro et al[26], 2021 | n = 18. Experimental group: 12 (neglect patients); Control group: 6 (healthy participants) | Digital test (touchscreen) | Left EN: > 2; Right EN: < -2; Left AN: > 1; Right AN: < -1 (apples test only) | 5 min (apples test only) | Traditional and digital versions are correlated and they yield very similar results, thus denoting them to be interchangeable |

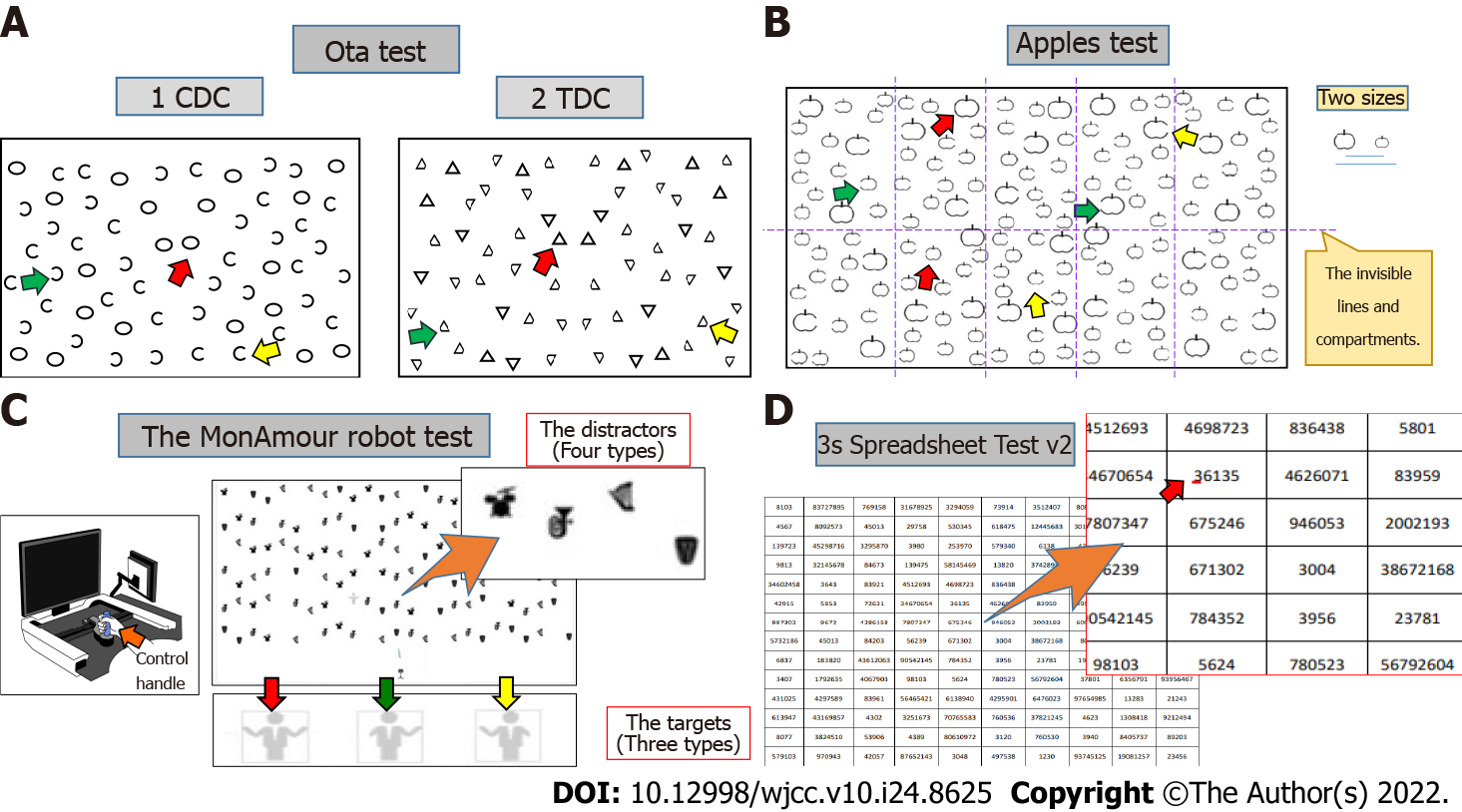

Ota et al[9] conducted a study in order to develop the Ota test for the differential diagnosis of EN and AN in two stroke patients with neglect following right hemisphere damage. In the development process, the two sub-assessments performed were circle discriminative cancellation (CDC) task and triangle discriminative cancellation (TDC) task. All tests were performed on an A3 paper. For the CDC task, 60 stimuli consisting of complete circle forms (20 stimuli, complete targets) and incomplete circle forms (40 stimuli: 20 left incomplete, 20 right incomplete, incomplete targets) were randomly scattered and placed. TDC task is similar to CDC task, except that the stimuli are in the form of triangles (Figure 2A). This test, which had no time limit, required the subjects to draw a circle to represent complete stimuli and a line to represent incomplete stimuli. Each test began with the paper presented in an upright position, followed by a re-test in which the paper was presented upside down. One test consisted of four trials (two CDC tasks and two TDC tasks). Results were obtained from all subjects who performed the second test similarly on a different day. The diagnostic methods suggested in this study are as follows. First, EN diagnosis was presented as an omission error by removing a circle in the complete stimuli on the left side of the test paper. Next, AN diagnosis was presented as a case in which the incomplete stimuli on the left were judged as complete stimuli and marked with a circle (false positive response), regardless of the location on the test paper. The study established differentiation by showing that subject 1 was EN and subject 2 was AN[9]. The limitations of this study are as follows. First, generalization may be difficult due to the small number of study participants. Second, the date interval between the tests and the reason for the four trials in this study were not clearly stated. Third, the severity of neglect cannot be examined because of the missing cut-off score. Therefore, it can only be used to distinguish EN from AN. Lastly, since there were two patients with left neglect, the study only showed the left-centered diagnostic methods for EN and AN. However, the diagnostic method for right neglect was not described.

Bickerton et al[12] compared the apples test, which can perform a differential diagnosis of EN and AN, with the star cancellation test, a standardized neglect assessment tool, in a validation study involving an experimental group (25 stroke patients) and a control group (86 normal subjects). All tests were conducted on an A4 paper, and 150 stimuli consisting of complete apple-shaped stimuli (50 stimuli, complete targets) and incomplete apple-shaped stimuli (100 stimuli: 50 left incomplete, 50 right incomplete, incomplete targets) were randomly scattered (Figure 2B). The test paper was divided into 10 invisible cells (5 columns and 2 rows). Each cell received 15 apple-shaped stimuli (3 large apples and 12 small apples), including complete apple-shaped stimuli and left or right incomplete apple-shaped stimuli. The subjects were specifically instructed to mark only the complete apple shape, regardless of size. The test, which had a time limit of 5 min, was performed with a simple preliminary test (up to 2 times) to familiarize the subjects with the test method. The diagnostic methods and cut-off scores proposed in the study are as follows. First, EN is diagnosed by comparing the correct answers in the left and right columns of the test paper. If the value obtained by subtracting the number of complete apple-shaped stimuli in the left cells from the selected number of complete apple-shaped stimuli in the right cells exceeds 2, it is presented as left side EN, and if it is less than -2, it is presented as right side EN. However, the middle 2 out of 10 cells were not used for scoring. Second, the difference in false positive responses based on the stimuli is used to diagnose AN. If the value obtained by subtracting the number of selected right incomplete apple-shaped stimuli (right incomplete targets) from the number of selected left incomplete apple-shaped stimuli (left incomplete targets) exceeds 1, it is presented as left side AN, and if it is less than -1, it is presented as right side AN. According to the study result, five subjects of the experimental group had EN, two had AN, and five had both EN and AN, thereby suggesting the possibility of differentiation. The apples test was found to be as sensitive and highly validated as the star cancellation test[12]. However, this study had limitations. First, the study had a relatively small number of subjects. Second, the preliminary test did not mention the practice paper. Third, a time limit was set for the test, but it was not used in the differential diagnosis process. Lastly, exact figures were not presented during the apples test validity verification process.

Demeyere et al[13] conducted a study involving an experimental group (208 stroke patients) and a control group (148 normal subjects) in order to develop the Oxford cognitive screen (OCS) to effectively measure cognitive function. The broken hearts test is a sub-test of OCS that can distinguish between EN and AN. During the development process, the sensitivity of the broken hearts test was compared to that of the star cancellation test, a standardized neglect evaluation tool. All tests were conducted on an A4 paper, and 150 stimuli consisting of complete heart-shaped stimuli (50 stimuli, complete targets) and incomplete heart-shaped stimuli (100 stimuli: 50 left incomplete, 50 right incomplete, incomplete targets) were randomly scattered and placed. In the test methods, the subjects were instructed to strike through the complete heart-shaped stimuli, regardless of heart size. The test, which had a time limit of 3 min, was performed after test method familiarization via a simple preliminary test. The diagnostic methods and cut-off scores proposed in the study are as follows. First, EN is compared by comparing the correct answers in the test paper’s left and right columns. If the value obtained by subtracting the number of complete heart-shaped stimuli in the left cells from the selected number of complete heart-shaped stimuli in the right cells exceeds 3, it is presented as left side EN, and if it is less than -3, it is presented as right side EN. However, the middle two out of ten cells were not used for scoring. Next, the difference of false positive responses based on the stimuli is used to diagnose AN. If the value obtained by subtracting the number of selected right incomplete heart-shaped stimuli (right incomplete targets) from the number of selected left incomplete heart-shaped stimuli (left incomplete targets) exceeds 1, it is presented as left side AN, and if it is less than -1, it is presented as right side AN. Based on the study result, 25% of the experimental group had EN, 11.9% had AN, and 13.6% had both EN and AN. The broken hearts test validation result was also very high at 94.12%[13]. Although a test time limit was set, it was not used in the differential diagnosis process.

Mizuno et al[24] conducted a study involving an experimental group (3 stroke patients, but only 2 had symptoms of neglect) and a control group (16 normal subjects) to develop the computerised cancellation test (CCT) for the differential diagnosis of EN and AN. During the development process, the conventional behavioral inattention test (BIT-C), a standardized neglect evaluation tool, was also implemented to verify CCT sensitivity. CCT can perform digital tests of circle discriminative cancellation task (CDC task), simple cancellation test, visuomotor search test, and visual search test through a 32-inch touch screen called TouchUbiCom; however, only the CDC task was able to perform a differential diagnosis of EN and AN. The computerized CDC task test presented in CCT is similar to the paper-based CDSC task test developed by Ota et al[9]. The difference is that a person has to touch the complete targets on the screen with a finger, and the result is automatically calculated. According to the study result, subject 1 presented with EN in the experimental group, subject 2 with AN, and the remaining one subject without neglect did not present with either EN or AN. Furthermore, CCT was found to be as sensitive as BIT-C[24]. The limitations of this study are as follows. First, generalization may be difficult due to the small number of study participants. Second, neglect severity cannot be examined because there is no cut-off score; thus, it can only be used to distinguish EN from AN. Third, requiring a special touch screen for the test may increase the cost. Lastly, exact figures were not presented in the CCT sensitivity verification process.

Montedoro et al[25] conducted a study involving an experimental group (35 stroke patients) and a control group (56 normal subjects) to develop the MonAmour robot test (MRT) for the differential diagnosis of EN and AN. During the development process, it was compared with the bells test, a standardized neglect evaluation tool, to verify MRT sensitivity. MRT used the REAplan® robot equipped with a test screen and a joystick (control handle). The screen is divided into 30 invisible cells (6 rows and 5 columns), and 120 stimuli were randomly placed, with four stimuli in each cell. The test employs human-shaped stimuli with raised hands (left, right, and both hands, targets) and four instrument-shaped stimuli (distractors) (Figure 2C). In 29 out of 30 cells, four instrument-shaped stimuli are presented, and one human-shaped stimulus (left hand: 30 times, right hand: 30 times, both hands: 30 times, and catch trial: 10 times) and three instrument-shaped stimuli are rearranged. The test, which included 100 trials at 7-s intervals, required the subject to push the joystick forward when a person raising both hands appeared, and to pull the joystick back when a person with one hand (left hand, right hand) appeared. The test was performed after familiarization with the test methods through a simple preliminary test (up to 10 times). The diagnostic methods suggested in this study are as follows. First, EN is diagnosed by comparing the mean reaction time on the right area or the number of non-responses (omission error) when human-shaped stimuli (left, right, and both hands) are presented in the left and right columns based on the test screen. If the value obtained by subtracting the number of responses that missed the human-shaped stimuli in the right column from the number of responses that missed the human-shaped stimuli in the left column is 1 or greater, it was presented as left side EN, and if it was -1 or less, it was presented as right side EN. Meanwhile, AN is diagnosed when human-shaped stimuli (including stimuli with either the left or right hand raised) respond in the opposite direction to the instruction (false positive response). If the value obtained by subtracting the number of opposite reactions to the human-shaped stimuli with a right hand raised (left incomplete targets) from the number of opposite reactions to the human-shaped stimuli with a left hand raised (right incomplete targets) is 1 or greater, it is presented as left side AN, and if it is -1 or less, it is presented as right side AN. Based on the study result, 19 subjects of the experimental group had EN, two had AN, and eight had both EN and AN, thereby suggesting the possibility of differentiation. The verified MRT sensitivity was found to be 84% of the overall standard, confirming a high correlation with the bells test[25]. The study’s limitations include economic burden and space for installation due to the specialized high-priced robot required.

Chen et al[23] conducted a study involving an experimental group (23 stroke or neglect patients) and a control group (186 normal subjects) in order to develop the 3 s spreadsheet test v2 for the EN and AN differential diagnosis. The test was conducted on a letter size paper (8.5 × 11 in) with 140 cells (10 cells per row and 14 cells per column), in which the digit strings served as stimuli. The digit strings had a minimum of four digits and a maximum of nine digits, with digits 0 to 9 being listed repeatedly. The test, which had no time limit, required the subject to find the correct answer 3 (targets) in all digit strings in the cell and strike through (correct answers: 120, other distractors: 720). If the digit strings are an odd number, 3 was not placed in the middle number (Figure 2D). The diagnostic methods and cut-off scores suggested in the study are as follows. First, EN diagnosis was analyzed by the difference in omission errors based on the test paper. If the value obtained by subtracting the number of omissions of the correct stimuli in the left region from the number of omissions of the correct stimuli in the right region exceeded 3, it was presented as left side EN, and if it was less than -3, it was presented as right side EN. For AN diagnosis, the digit strings were divided in half based on the digit strings presented for each cell in the test. If the value obtained by subtracting the number of omissions of the correct stimuli in the right area from the number of omissions of the correct stimuli in the left area exceeded 5, it was presented as left side AN, and if it was less than -3, it was presented as right side AN. Based on the study result, three out of 23 subjects in the experimental group had EN, two had AN, and 18 had both EN and AN, thereby suggesting the possibility of differentiation[23]. The study’s limitation is that the subjects may experience high test fatigue due to the 840 stimuli, which is higher compared to the other tests.

Ferraro et al[26] investigated the possibility of replacing the pen and paper test with digital tests such as Albert’s test, line bisection test, and apples test built in the ReMoVES platform for an experimental group (12 neglected patients) and a control group (6 normal patients)[26]. The ReMoVES platform is a computerized test program developed by the University of Genova, and only the apples test was able to differentiate between EN and AN among the three built-in tests. The computerized apples test presented in the ReMoVES platform is similar to the paper-based apples test studied by Mancuso et al[27]. However, it requires touching the complete apple-shaped stimuli presented on the screen with a finger, and the result is automatically calculated. The study result showed that the paper-based test and computerized test produced similar results in the subject's test performance process, and they can be used interchangeably[26]. The limitations of this study are as follows. First, personal information (e.g., gender, age, and disease) was not presented for the 12 experimental groups. Finally, generalization is difficult due to the small number of study participants (Figure 2).

AN has more adverse effects on cognitive function, activities of daily living, and rehabilitation speed than EN. It was also confirmed that the existing neglect treatment had no significant effect on AN patients. Therefore, seven assessment tools that can effectively differentially diagnose EN and AN were analyzed.

First, the study results showed that cancellation test type tests were developed in the studies as the most common feature, and the test stimuli presented during the research process were commonly encountered shapes in everyday life, such as circles, triangles, apples, hearts, and numbers[9,12,13,23-26]. Furthermore, it has been confirmed that the stimuli presented in most studies were complete forms and left or right incomplete[9,12,13,24-26]. According to the diagnostic methods presented in this study, EN is mainly the difference in the number of correct answers in the left and right areas on the test paper or screen, and AN was presented as the difference in the number of incorrect answers on incomplete forms in the left and right areas based on stimuli (false positive response)[9,12,13,24,26]. This is thought to be presented for accurate differential diagnosis, taking into account the concept of EN neglecting information centered on the individual (self) and AN neglecting information centered on the object (stimuli). However, the MonAmour robot test studied by Montedoro et al[25] showed both the EN and AN diagnostic methods presented as a difference in the number of incorrect answers (non-response, opposite response). In comparison with the other tests, it is considered to be the diagnostic method designed according to the test characteristics, in which the stimuli are newly rearranged for each trial, and must respond to both correct and incorrect answers. According to the study conducted by Chen et al[23] on ‘3s spreadsheet test v2’, both the EN and AN diagnostic methods were presented as the difference in the number of omission of correct answers (omission errors). In comparison with the other tests, it is considered to be the diagnostic method designed according to the test characteristics, in which the stimuli used are presented only as the correct stimuli (targets) and other stimuli (distractors). Furthermore, four articles reviewed the pencil and paper tests[9,12,13,23], and three articles reviewed the digital[24-26]. All of the seven presented assessment tools can effectively perform a differential diagnosis of EN and AN, and Ferraro et al[26] confirmed that the paper-based test and the digital test are interchangeable with each other.

The limitations of the studies are as follows. First, they are difficult to generalize due to the small number of study subjects[9,24,26]. Second, although the diagnostic criteria for EN and AN were presented, a cut-off score to evaluate the severity of neglect was not presented[9,24]. Third, accurate figures were not presented in the assessment tool verification process[12,24]. Fourth, the diagnostic criteria for EN and AN were only focused on the left side, so the diagnosis criteria for right neglect were not presented[9,24]. Fifth, although the time limit of the test was set, it was not used to determine the degree of neglect[12,13]. Lastly, there are issues in regard to space due to cost and installation location for the digital tests[24,25]. In future studies, the following is recommended to complement the limitations of the previous studies: (1) Conduct research with a sufficient number of subjects; (2) Provide a cut-off score required in order to confirm the severity of neglect; (3) Suggest the severity according to the type of neglect by using the time limit of the test; and (4) Consider economic and spatial problems caused by the equipment required for the digital tests.

In this study, we review the literature studying assessment tools for the differential diagnosis of EN and AN. Accordingly, seven tests (pencil and paper: 4 times, digital test: 3 times) were tested and effective, and differential diagnosis can be conducted when the difference in response to various stimuli is used.

In conclusion, these results might offer an easier differential diagnosis of AN, and appropriate intervention at an early stage of injury. In the case of a patient with both EN and AN, it might be possible to seamlessly modify the detailed direction of intervention by determining the improvement of neglect via continuous assessment. Finally, the data discussed in this work may provide guidance for developing more convenient and various differential diagnosis methods and new intervention methods for AN as diverse as those for EN.

There are various types of neglect, and the symptoms are also diverse. However, review studies on the differential diagnosis of the relatively recently discovered allocentric neglect (AN) and the already known egocentric neglect (EN) are lacking.

Compared to EN, AN has a more adverse effect on daily life, and the recovery rate is lower. In addition, the conventional treatment for EN is not effective in the treatment of AN. Therefore, the distinction between AN and EN is very important.

By reviewing the studies on differential diagnosis, we tried to find out the overall trend of the newly developed evaluation tools.

A literature search on differential diagnosis was conducted through a search according to appropriate keywords.

Seven relevant papers were collected (paper-and-pencil 4, digital 3).

All tests were effective in the differential diagnosis of EN and AN.

A more effective intervention will be possible through an accurate differential diagnosis. It is hoped that more treatments for AN will be developed in the future.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Rehabilitation

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cao X, China; Cristaldi PMF, Italy S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Vallar G, Calzolari E. Unilateral spatial neglect after posterior parietal damage. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;151:287-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Urbanski M, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Rodrigo S, Catani M, Oppenheim C, Touzé E, Chokron S, Méder JF, Lévy R, Dubois B, Bartolomeo P. Brain networks of spatial awareness: evidence from diffusion tensor imaging tractography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:598-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rorden C, Hjaltason H, Fillmore P, Fridriksson J, Kjartansson O, Magnusdottir S, Karnath HO. Allocentric neglect strongly associated with egocentric neglect. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:1151-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Heilman KM, Valenstein E, Watson RT. Neglect and related disorders. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:463-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pedroli E, Serino S, Cipresso P, Pallavicini F, Riva G. Assessment and rehabilitation of neglect using virtual reality: a systematic review. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jehkonen M, Ahonen JP, Dastidar P, Koivisto AM, Laippala P, Vilkki J, Molnár G. Predictors of discharge to home during the first year after right hemisphere stroke. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;104:136-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shah PP, Spaldo N, Barrett AM, Chen P. Assessment and functional impact of allocentric neglect: a reminder from a case study. Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;27:840-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gillen R, Tennen H, McKee T. Unilateral spatial neglect: relation to rehabilitation outcomes in patients with right hemisphere stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:763-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ota H, Fujii T, Suzuki K, Fukatsu R, Yamadori A. Dissociation of body-centered and stimulus-centered representations in unilateral neglect. Neurology. 2001;57:2064-2069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Medina J, Kannan V, Pawlak MA, Kleinman JT, Newhart M, Davis C, Heidler-Gary JE, Herskovits EH, Hillis AE. Neural substrates of visuospatial processing in distinct reference frames: evidence from unilateral spatial neglect. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21:2073-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen P, Caulfield MD, Hartman AJ, O'Rourke J, Toglia J. Assessing viewer-centered and stimulus-centered spatial bias: The 3s spreadsheet test version 1. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2017;24:532-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bickerton WL, Samson D, Williamson J, Humphreys GW. Separating forms of neglect using the Apples Test: validation and functional prediction in chronic and acute stroke. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:567-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Demeyere N, Riddoch MJ, Slavkova ED, Bickerton WL, Humphreys GW. The Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS): validation of a stroke-specific short cognitive screening tool. Psychol Assess. 2015;27:883-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen P, Hreha K, Kong Y, Barrett AM. Impact of spatial neglect on stroke rehabilitation: evidence from the setting of an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1458-1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moore MJ, Vancleef K, Riddoch MJ, Gillebert CR, Demeyere N. Recovery of Visuospatial Neglect Subtypes and Relationship to Functional Outcome Six Months After Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2021;35:823-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gossmann A, Kastrup A, Kerkhoff G, López-Herrero C, Hildebrandt H. Prism adaptation improves ego-centered but not allocentric neglect in early rehabilitation patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27:534-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Upshaw JN, Leitner DW, Rutherford BJ, Miller HBD, Libben MR. Allocentric Versus Egocentric Neglect in Stroke Patients: A Pilot Study Investigating the Assessment of Neglect Subtypes and Their Impacts on Functional Outcome Using Eye Tracking. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2019;25:479-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Luauté J, Halligan P, Rode G, Rossetti Y, Boisson D. Visuo-spatial neglect: a systematic review of current interventions and their effectiveness. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:961-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vahlberg B, Hellström K. Treatment and assessment of neglect after stroke–from a physiotherapy perspective: a systematic review. Adv Physiother. 2008;10:178-187. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kashiwagi FT, El Dib R, Gomaa H, Gawish N, Suzumura EA, da Silva TR, Winckler FC, de Souza JT, Conforto AB, Luvizutto GJ, Bazan R. Noninvasive Brain Stimulations for Unilateral Spatial Neglect after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized and Nonrandomized Controlled Trials. Neural Plast. 2018;2018:1638763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pierce SR, Buxbaum LJ. Treatments of unilateral neglect: a review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:256-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Stowman SA, Donohue B. Assessing child neglect: A review of standardized measures. Aggress Violent Behav. 2005;10:491-512. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Chen P, Toglia J. The 3s Spreadsheet Test version 2 for assessing egocentric viewer-centered and allocentric stimulus-centered spatial neglect. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2021;1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mizuno K, Kato K, Tsuji T, Shindo K, Kobayashi Y, Liu M. Spatial and temporal dynamics of visual search tasks distinguish subtypes of unilateral spatial neglect: Comparison of two cases with viewer-centered and stimulus-centered neglect. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2016;26:610-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Montedoro V, Alsamour M, Dehem S, Lejeune T, Dehez B, Edwards MG. Robot Diagnosis Test for Egocentric and Allocentric Hemineglect. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2019;34:481-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ferraro F, Trombini M, Truffelli R, Simonini M, Dellepiane S. On the assessment of unilateral spatial neglect via digital tests. Proceedings of the 10th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering; 2021 May 4-6; New York: IEEE, 2021: 802-806. |

| 27. | Mancuso M, Rosadoni S, Capitani D, Bickerton WL, Humphreys GW, De Tanti A, Zampolini M, Galardi G, Caputo M, De Pellegrin S, Angelini A, Bartalini B, Bartolo M, Carboncini MC, Gemignani P, Spaccavento S, Cantagallo A, Zoccolotti P, Antonucci G. Italian standardization of the Apples Cancellation Test. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:1233-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |