Published online Aug 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8277

Peer-review started: February 16, 2022

First decision: May 30, 2022

Revised: June 5, 2022

Accepted: July 11, 2022

Article in press: July 11, 2022

Published online: August 16, 2022

Processing time: 165 Days and 22.4 Hours

Combined tumors comprising large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma have been rarely reported in the literature.

We report a case of a 73-year-old woman with chronic hepatitis B suspected to have a malignant hepatic mass (segment 3; size, 4.5 cm) and lymph node metastasis based on computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Despite being Child-Pugh class A, esophageal varices were present. She underwent left lateral sectionectomy and lymph node dissection. Pathological examination revealed a collision tumor consisting of large-cell neuroendocrine (90%) and hepatocellular (10%) carcinomas. The combined carcinoma had metastasized to one of the three lymph nodes excised. The patient recovered without any postoperative complications and was discharged in good condition on postoperative day 13. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not performed. No recurrence occurred during a follow-up period of 24 mo.

To improve the therapeutic management of combined tumors in the liver, it is necessary to discuss each clinical experience and consider an appropriate method for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment.

Core Tip: Collision tumors originating from the liver are extremely rare. No rational surgical strategies for these tumors have been reported because of their rarity, the shortness of knowledge of predictive prognostic factors, the inability to identify progression, and the limited understanding of the biohistology of these lesions. However, complete resection of a resectable locoregional neuroendocrine tumor has excellent outcomes. Because of their rarity, there are no proper guidelines for adjuvant treatment. It is necessary to discuss each clinical experience and consider an appropriate method for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment.

- Citation: Noh BG, Seo HI, Park YM, Kim S, Hong SB, Lee SJ. Complete resection of large-cell neuroendocrine and hepatocellular carcinoma of the liver: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(23): 8277-8283

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i23/8277.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8277

Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma is rare, accounting for 0.3% of all neuroendocrine tumors (NETs)[1]. To date, only a few cases have been reported[1]. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is poorly differentiated, and its occurrence in the liver has been rarely studied. Preoperative diagnosis is difficult, and most cases are diagnosed postoperatively. Resection of the primary hepatic NET is primary treatment[2] because the biological behavior of neuroendocrine carcinoma is more aggressive than that of adenocarcinoma[3]. We report a rare case of a combined primary tumor [large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (90%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (10%)] of the liver. Through its pathogenesis and prognosis, we hope that clinicians will gain a better clinical understanding of collision tumors.

A 73-year-old woman presented with a hepatic mass discovered during a periodic follow-up for chronic hepatitis B.

The patient reported no clinical symptoms of illness. She also had a negative medical history.

The patient reported no family history of malignant tumors.

The clinical examination showed no tenderness in her abdomen. No palpable mass was detected. Her general condition was good.

Hepatobiliary and tumor enzyme levels (carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, alpha-fetoprotein, and protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-III) were all normal findings.

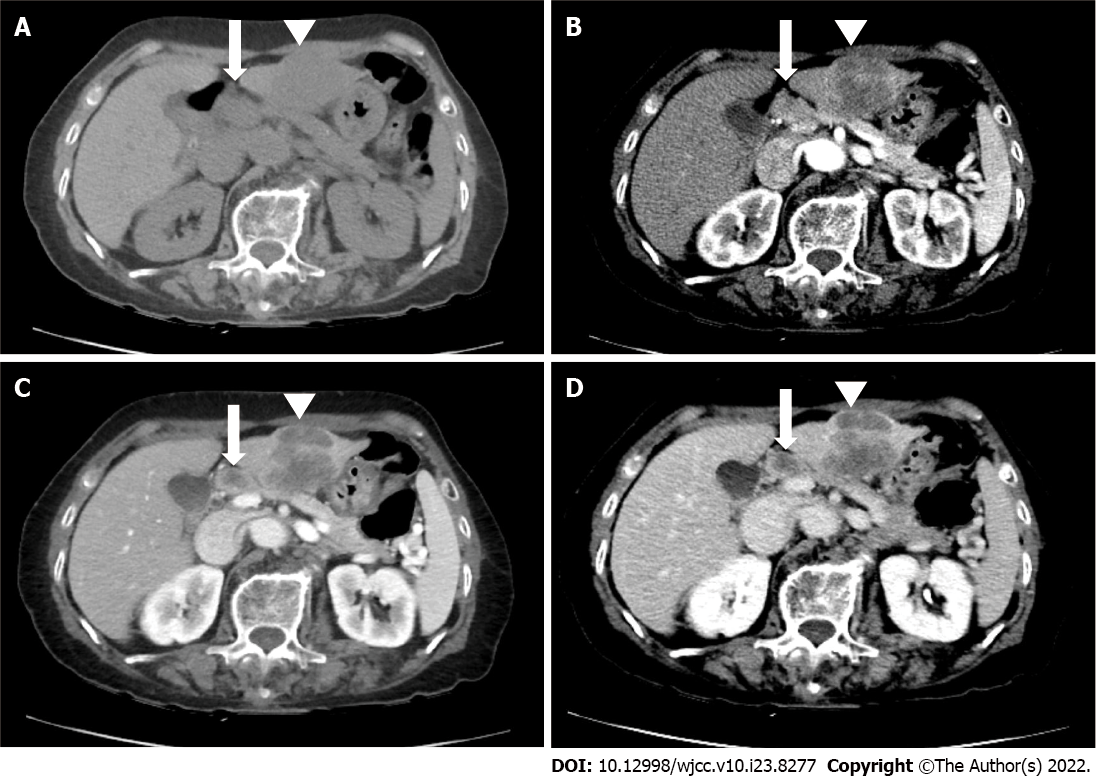

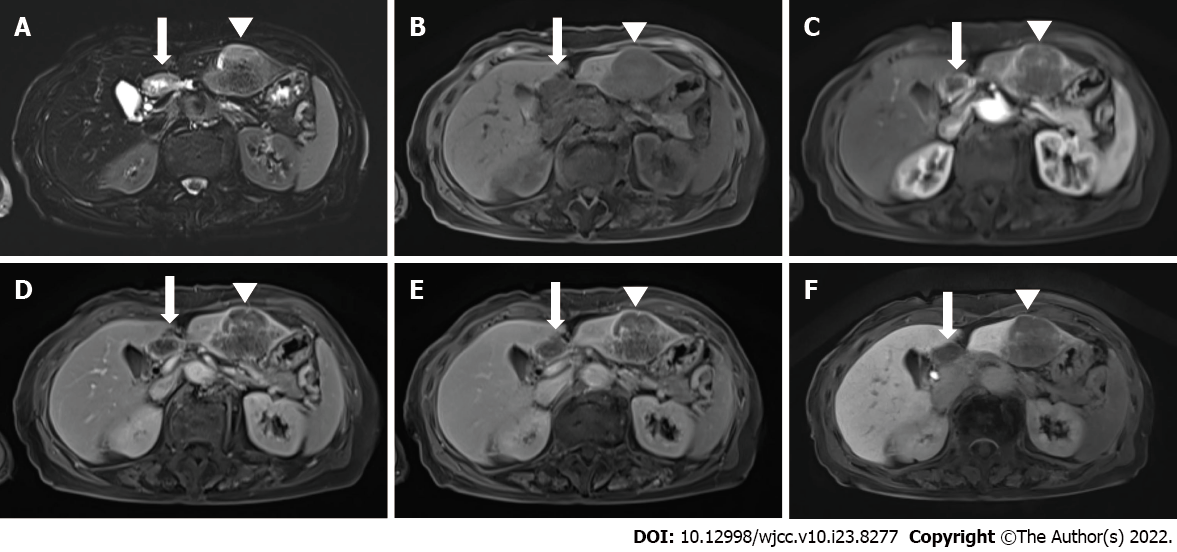

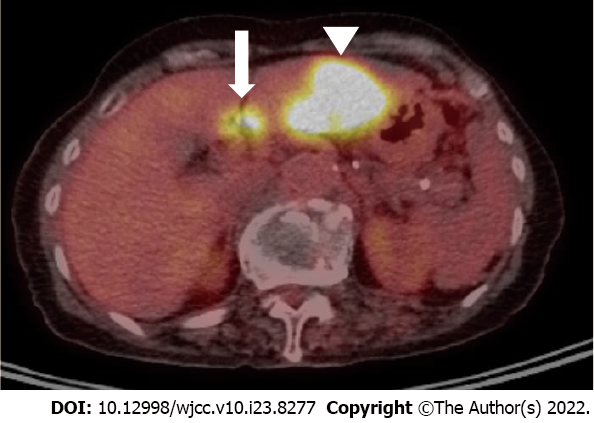

Upper abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a solitary 4.5-cm mass lesion in segment 3 of the liver (Figures 1 and 2). The preoperative imaging diagnosis was an atypical hepatocellular carcinoma or hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma combined with lymph node metastasis. The patient refused biopsy and decisively wanted surgery. However, a routine workup was performed to check for metastasis. The chest CT and bone scan showed no metastatic lesions. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-CT was performed to exclude the possibility of neuroendocrine tumors of the liver metastasizing from neuroendocrine carcinomas of other organs. Two hypermetabolic lesions (SUVmax, 12.6 and 7.8) in the left lateral section were detected using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography. No uptake was seen in the metastatic lymph nodes (Figure 3).

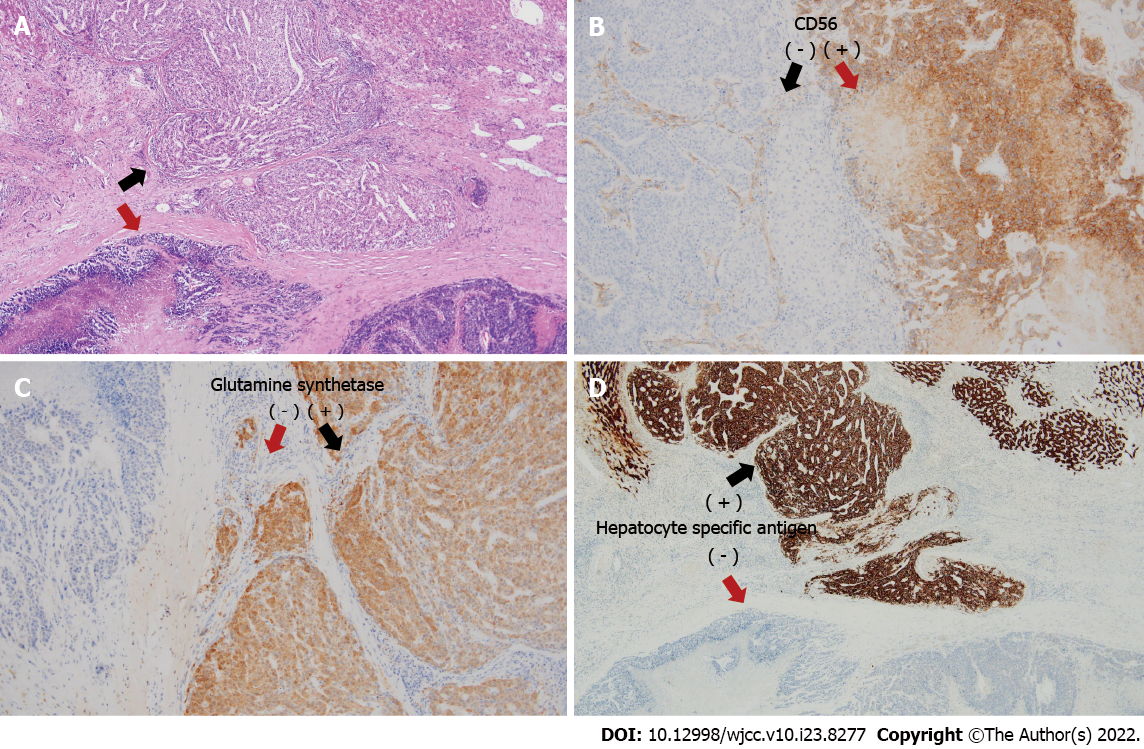

We performed a left lateral sectionectomy and lymph node dissection around the hepatoduodenal ligament, retropancreas, and celiac trunk. Histopathology confirmed a collision tumor consisting of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (90%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (10%) without a transitional zone. The solitary tumor was 6.0 cm × 5.0 cm × 3.5 cm in size. Ninety percent of the tumor consisted of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma with a mitotic count of 110 per 10 high-power fields; it was positive for CD56 and negative for synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and glypcan-3 staining patterns. The other 10% of the tumor consisted of a hepatocellular carcinoma that was positive for glutamine synthetase, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 19, hepatocyte-specific antigen, arginase-1, and CD34 staining patterns according to immunohistochemistry (Figure 4). Necrosis was observed in 50% of the tumor. One of the three resected lymph nodes was metastatic and contained neuroendocrine carcinoma without extranodal extension. The neuroendocrine carcinoma component showed lymphovascular invasion. The liver had an 18-mm tumor-free margin.

Based on the histopathology results, the final diagnosis was a collision tumor consisting of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (90%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (10%) with lymph node metastasis.

After complete resection of combined tumor and lymph node dissection around the hepatoduodenal ligament, retropancreas, and celiac trunk. The patient was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 10 and refused adjuvant chemotherapy.

She was followed-up as an outpatient for 24 mo during which she had no recurrence.

The co-occurrence of two distinct tumors in the liver is histologically classified as a collision or combined tumor. It can show as a collision tumor in which properties of both tumors mixed and cannot be significantly separated in the transitional part within a single tumor lesion. A co-occurrence tumor presents two histologically different tumors involving the same body part with no histologic aggregation. They co-exist with distance or adherence, in which the tumors are divided by a fibrous tissue[4]. In our case, the small hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) component (10%) was floating within the large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. The etiological identification of neuroendocrine components in a combined NEC and HCC remains controversial. If a poorly developed tumor clone of HCC undergoes neuroendocrine differentiation and transforms into an NEC, then it is possible for an original HCC to be completely replaced by NEC[5]. This statement aligns with the findings of our report. Immunohistochemical staining with chromogranin-A, synaptophysin, and CD56 was performed on the resected specimens for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs). Positive staining of > 2 of these markers has been reported in > 80% of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs)[6]. However, primary NEC with concurrent HCC is rare. NECs, mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms, or collision tumors originating from the liver are extremely rare, and preoperative diagnosis can be difficult, especially in areas with a high prevalence of HCC. The management of NENs is complicated; therefore, histologic grading and staging of the lesion are essential for proper decision making. No rational surgical strategies for these tumors have been reported for various reasons, including the rarity of the disease, the lack of predictive prognostic factors, the inability to identify progression, and the limited understanding of the biology of the lesion[7]. However, a complete resection of the resectable locoregional NET has excellent outcomes. Nodal involvement appears to have low significance in long-term survival. Because a more advanced stage does not predict a worse prognosis, staging using the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM and European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society staging systems is insufficient in predicting prognosis. However, surgical resection with regional node resection is necessary for treatment and staging[8]. Despite the progress of imaging techniques, preoperative diagnosis of NETs is still complicated. In particular, cholangiocarcinoma has similar characteristics and morphology to NETs on various imaging modalities including ultrasound, CT and MRI. Preoperative tissue confirmation can be helpful, and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy is considered to be more useful than endoscopic biopsy alone in obtaining an accurate preoperative diagnosis. However, preoperative biopsy cannot differentiate NET from NEC. Chromogranin A is known to be escalated in ninety percent of gut NETs and is related to tumor load and recurrence[9]. Consequently, serum chromogranin A could be a valuable marker for the diagnosis of NETs prior to surgery. However, it is not pragmatic because of the rarity of NETs. In our case, adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide was recommended post-surgery because the patient had a 90% large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. However, the patient refused adjuvant treatment. No recurrence was observed after the curative surgery. We performed a retrospective review at a single center. A prospective, randomized, multicenter investigations related to this issue are necessary.

Because combined tumors based on neuroendocrine carcinoma in the liver are rare, there are no proper guidelines for their treatment. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy may not be required after complete resection of combined tumors of the liver with lymph node metastasis. To improve the therapeutic management of combined tumors in the liver, it is necessary to discuss each clinical experience and consider an appropriate method for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cheng H, China; Hu HG, China S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Fenwick SW, Wyatt JI, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP. Hepatic resection and transplantation for primary carcinoid tumors of the liver. Ann Surg. 2004;239:210-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gravante G, De Liguori Carino N, Overton J, Manzia TM, Orlando G. Primary carcinoids of the liver: a review of symptoms, diagnosis and treatments. Dig Surg. 2008;25:364-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shimizu T, Tajiri T, Akimaru K, Arima Y, Yoshida H, Yokomuro S, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Mizuguchi Y, Kawahigashi Y, Naito Z. Combined neuroendocrine cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder: report of a case. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Garcia MT, Bejarano PA, Yssa M, Buitrago E, Livingstone A. Tumor of the liver (hepatocellular and high grade neuroendocrine carcinoma): a case report and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:376-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ishida M, Seki K, Tatsuzawa A, Katayama K, Hirose K, Azuma T, Imamura Y, Abraham A, Yamaguchi A. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma coexisting with hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C liver cirrhosis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:214-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Derks JL, Dingemans AC, van Suylen RJ, den Bakker MA, Damhuis RAM, van den Broek EC, Speel EJ, Thunnissen E. Is the sum of positive neuroendocrine immunohistochemical stains useful for diagnosis of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) on biopsy specimens? Histopathology. 2019;74:555-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Eltawil KM, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Modlin IM. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gallbladder: an evaluation and reassessment of management strategy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:687-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Burns WR, Edil BH. Neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors: guidelines for management and update. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13:24-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Modlin IM, Gustafsson BI, Moss SF, Pavel M, Tsolakis AV, Kidd M. Chromogranin A--biological function and clinical utility in neuro endocrine tumor disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2427-2443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |