Published online Aug 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i22.7844

Peer-review started: September 8, 2021

First decision: December 4, 2021

Revised: December 11, 2021

Accepted: June 27, 2022

Article in press: June 27, 2022

Published online: August 6, 2022

Processing time: 316 Days and 17.8 Hours

Split-dose regimens (SpDs) of 4 L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) have been established as the “gold standard” for bowel preparation; however, its use is limited by the large volumes of fluids required and sleep disturbance associated with night doses. Meanwhile, the same-day single-dose regimens (SSDs) of PEG has been recommended as an alternative; however, its superiority compared to other regimens is a matter of debate.

To compare the efficacy and tolerability between SSDs and large-volume SpDs PEG for bowel preparation.

We searched MEDLINE/PubMed, the Cochrane Library, RCA, EMBASE and Science Citation Index Expanded for randomized trials comparing (2 L/4 L) SSDs to large-volume (4 L/3 L) SpDs PEG-based regimens, regardless of adjuvant laxative use. The pooled analysis of relative risk ratio and mean difference was calculated for bowel cleanliness, sleep disturbance, willingness to repeat the procedure using the same preparation and adverse effects. A random effects model or fixed-effects model was chosen based on heterogeneity analysis among studies.

A total of 18 studies were included. There was no statistically significant difference of adequate bowel preparation (relative risk = 0.97; 95%CI: 0.92-1.02) (14 trials), right colon Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (mean difference = 0.00; 95%CI: -0.04, 0.03) (9 trials) and right colon Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale (mean difference = 0.04; 95%CI: -0.27, 0.34) (5 trials) between (2 L/4 L) SSDs and large-volume (4 L/3 L) SpDs, regardless of adjuvant laxative use. The pooled analysis favored the use of SSDs with less sleep disturbance (relative risk = 0.52; 95%CI: 0.40, 0.68) and lower incidence of abdominal pain (relative risk = 0.75; 95%CI: 0.62, 0.90). During subgroup analysis, patients that received low-volume (2 L) SSDs showed more willingness to repeat the procedure using the same preparation than SpDs (P < 0.05). No significant difference in adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting and bloating, was found between the two arms (P > 0.05).

Regardless of adjuvant laxative use, the (2 L/4 L) SSD PEG-based arm was considered equal or better than the large-volume (≥ 3 L) SpDs PEG regimen in terms of bowel cleanliness and tolerability. Patients that received low-volume (2 L) SSDs showed more willingness to repeat the procedure using the same preparation due to the low-volume fluid requirement and less sleep disturbance.

Core Tip: Same-day single-dose polyethylene glycol-based regimens for bowel preparation seemed to be equal or better than large-volume (≥ 3 L) split-dose polyethylene glycol solution in terms of bowel cleanliness and tolerability as long as the optimal preparation-to-colonoscopy interval and diet instruction for bowel preparation were respected.

- Citation: Pan H, Zheng XL, Fang CY, Liu LZ, Chen JS, Wang C, Chen YD, Huang JM, Zhou YS, He LP. Same-day single-dose vs large-volume split-dose regimens of polyethylene glycol for bowel preparation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(22): 7844-7858

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i22/7844.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i22.7844

A colonoscopy is an important tool used for colorectal cancer screening and the management of colorectal lesions. However, the success of colonoscopy is strongly dependent on the quality of bowel preparation. Prior studies have reported that poor bowel preparation can increase the risk of missed diagnosis for smaller and/or flat lesions, especially in the right colon, and prolong cecal intubation time[1,2]. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) solutions, as efficient and safe purgative agents, offer the advantage of minimal fluid and electrolyte shifts and are reportedly the most widely used solutions for bowel preparation[1-3].

High volume (4 L) split-dose regimens (SpDs) of PEG have been recommended as the gold-standard regimen for bowel preparation[4]; however, the large volume of fluids or poor tolerability associated with SpDs have become a source of patient dissatisfaction. The same-day single-dose (SSD) PEG has been recommended as an alternative for patients scheduled for afternoon colonoscopy[5,6], exhibiting equal cleansing efficacy and fewer sleep disturbances than SpDs. Meanwhile, it was reported to be in favor of reducing the preparation volume and improving patient tolerance by using PEG solution combined with adjuvant laxative agents for those at risk of bowel preparation[7]. A previous systematic review by Enestvedt et al[8] revealed that 4 L split-dose PEG was better than other bowel preparation comparators including a regimen of 4 L single-dose PEG the night before the procedure and MiraLAX/Gatorade solutions, regardless of adjuvant laxative use. However, in order to evaluate bowel cleanliness of the SSD regimens of PEG and patient tolerance in terms of sleep disturbances and side effects for bowel preparation, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and tolerability of SSD PEG-based arm vs large-volume (≥ 3 L) split-dose PEG solutions for bowel preparation before colonoscopy, regardless of adjuvant laxative use.

Systemic searches were performed in June 2021 using MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Google Scholar and Cochrane Library by two independent reviewers. The search strategy used the Medical Subject Heading term along with the keywords “polyethylene glycol, (bowel preparation OR bowel preparation solution), (split dose OR split-dose) and randomized controlled.” Only full texts published in English with one arm using single-dose PEG on the day of colonoscopy, regardless of adjuvant laxative use and the other arm consisting of a split-dose regimen of PEG for bowel preparation before and on the day of the procedure, were included. References from the reviewed articles were also searched to identify relevant articles that may have been missed.

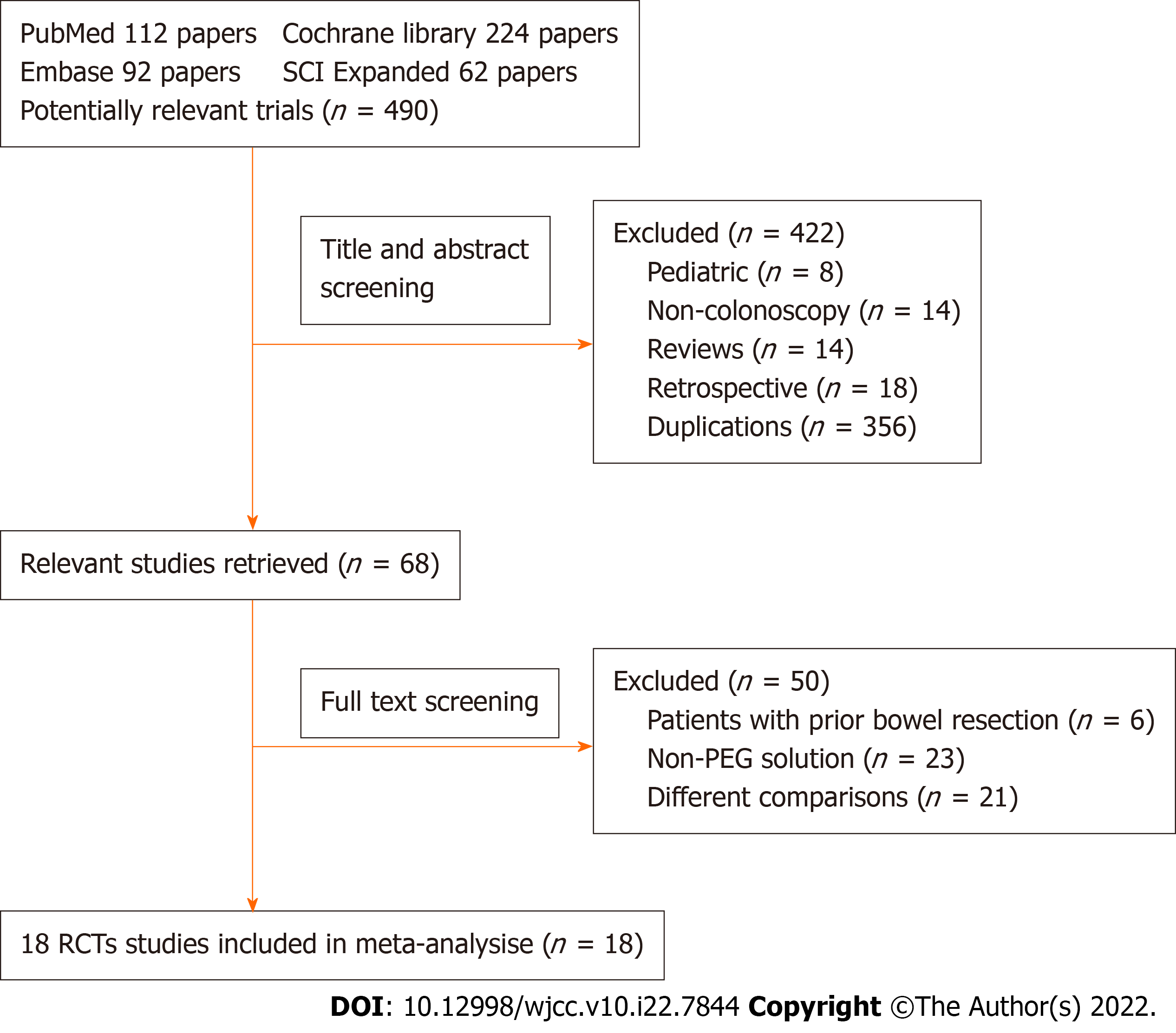

Exclusion criteria consisted of the following: (1) Participants: pediatric patients, cases of prior colorectal resection and incomplete or complete bowel obstruction cases; (2) Non-colonoscopy studies; (3) Interventions: non-PEG-based solution (i.e. sodium phosphate, picosulfate, sodium picosulfate with magnesium citrate agents, etc); and (4) Comparisons: trials comparing evening-before vs split-dose, twice a same-day vs split-dose and low-volume (≤ 2 L) split-dose. A flowchart of the literature search is shown in Figure 1.

Two authors independently conducted the screening and extracted the data from selected trials with the intention to treat numbers preferred. Results from included studies reported as percentages were converted to absolute numbers.

The methodological quality of each study was graded by two investigators using a modified Jadad scoring system utilized for single (endoscopist) blinding trials[8]. This 5-point scale assigns a single point for each of the following: (1) The study is described as randomized; (2) The randomization method is described and appropriate; (3) The study is described as blind; (4) The blinding method is described and appropriate; and (5) There is a description of withdrawals and drop-outs. A score of 5 suggested excellent quality, and a score of 0 implied a poor-quality randomized controlled trial. Single-blinding rather than double-blinding can be executed logistically for bowel preparation studies. To ensure the adequacy of blinding, all endoscopists were blinded to the bowel preparation, and staff, nurses and patients were instructed not to discuss the bowel preparation with the endoscopist. The funnel plot was used to assess publication bias. The Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach was presented to rate the certainty of evidence. Points of disagreement were reconciled by a discussion with another author when required.

The primary outcome measure was bowel cleanliness, defined as adequate bowel preparation using validated scales [Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale (OBPS) or Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS)]. Secondary outcomes included the willingness to repeat the procedure using the same preparation, sleep disturbance and side effects, including nausea, vomiting, bloating and abdominal pain/cramps.

The total OBPS score was based upon the sum of the right, transverse and left colonic segments (reference range of 0-4 each segment) plus an overall colonic fluid score (range 0-2)[9]. The total score ranged from 0 to 14; the lower the score, the better the preparation. The total BBPS score was the sum of the right colon, mid-colon and left colonic segmental scale. The total score ranged from 0 to 9 (0 = very poor, 9 = excellent)[10].

Statistical analysis was conducted with Review Manager (Version 5.4, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, GB). The categorical outcomes were analyzed using relative risk ratio (RR) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Continuous data were analyzed using mean differences (MD) and corresponding 95%CI. Statistical heterogeneity was measured by graphic examination of forest plots and statistically through a homogeneity test based on the χ2 test (I2 ≥ 50% suggests heterogeneity) in which P < 0.10 was considered significant for heterogeneity. A fixed-effects model was used unless there was significant heterogeneity, in which case a random-effects model was applied. Weighted MDs were used for outcomes measured on different scales. A RR > 1 favored the SSD arm, while a RR < 1 favored the SpDs arm for the favorable outcomes (adequate preparation and willingness to repeat) and the adverse outcomes (sleep disturbance and adverse effects). The MD represented the difference in means between SSD and SpDs (SSD – SpDs = MD); an MD > 0 favored the SSD arm, while an MD < 0 favored the SpDs arm. A higher mean BBPS score indicated better quality of bowel preparation, which was the opposite for OBPS scores. Subgroup analysis was performed to characterize heterogeneity and sensitivity.

The initial search identified 490 potentially relevant articles. A total of 422 articles were excluded based on titles and abstracts because they included patients < 18 years of age, non-colonoscopy studies, reviews, retrospective studies or duplications. Sixty-eight articles were reviewed by full text. Overall, 18 articles[11-28] comparing bowel preparation with SSDs vs SpDs PEG were included in this analysis. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of studies from initial results of publication searches to final inclusion or exclusion.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 18 included studies (n = 5464), which consisted of 2793 patients who received SSDs and 2671 patients who received the SpDs regimen. Nine trials evaluated low-volume (2 L) SSD PEG with adjuvant laxative use vs large-volume(≥ 3 L) SpDs PEG[11,12, 22-28], four trials compared 4 L SSD PEG vs 4 L SpDs PEG[13,14,19,20], and six trials compared 2 L SSD PEG vs (≥ 3 L) SpDs PEG[11,15-18,21]. Interestingly, in a study by Zhang et al[11], patients were assigned to three groups: 2 L SSD PEG, 2 L SSD PEG with adjuvant laxative (linaclotide) and 4 L SpDs PEG.

| Ref. | Type of study | Participants and years of age | Bowel preparation | Patients with SSD/SpDs, n | Diet instruction | Colonoscopy timing | Outcomes | Interval, PC | Jadad score, modified | Use of adjuvant |

| Zhang et al[11], 2021 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients 18-70 yr | SSD (A): 2 L PEG 6 h before procedure; SSD (B): 290 µg Lin 7 h before + 0.5 L water, 2 L PEG 6 h before colonoscopy; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 21:00 the day prior, 2 L PEG 6 h before colonoscopy | 139A/141B/140 | 1-d LRD | Morning: 8:00-11:30; Afternoon: 13:30- 17:00 | BBPS | 6 h | 4 | SSD (B): Linaclotide |

| Barkun et al[12], 2020 | Multicenter, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients ≥ 18 yr | SSD: 2 L PEG 4 h before colonoscopy + 15 mg bis at 14:00 the day before; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 19:00 the day before, 2 L PEG 4-5 h before colonoscopy | 583/582 | Not described | 10:30-16:30 | BBPS | 2-3 h | 5 | Bisacodyl |

| Castro et al[13], 2019 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients ≥ 18 yr | SSD: 4 L PEG at 6:00; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 18:00 the day before, 2 L PEG 6 h before colonoscopy | 142/158 | CLD after regular breakfast the day before | 13:00-16:30 | OBPS | Not described | 5 | No |

| Seo et al[14], 2019 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients 40–75 yr | SSD (Mor): 4 L PEG at 5:00; SSD (Aft): 2 L PEG at 7:00 + 2 L PEG at 10:00; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 21:00 the day before, 2 L PEG at 7:00 (Mor) or at 10:00 (Aft) | 172/167 | LFF for 2 d, soft diet dinner the day prior | Morning 10:00-12:00; Afternoon 13:30-17:00 | BBPS | Not described | 3 | No |

| Kang et al[15], 2018 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Patients 18-70 yr | SSD: 2 L PEG 4-6 h before colonoscopy; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 19:00-21:00 the day before, 2 L PEG 4-6 h before colonoscopy | 470/470 | Regular meal for lunch and CLD or LRD for dinner the day before | Morning 8:30-12:00; Afternoon 13:00-16:00 | BBPS | 2-4 h | 5 | No |

| Zhang et al[16], 2015 | Multicenter, single-blind, RCT | Patients 18-75 yr | SSD: 2 L PEG 4-6 h before colonoscopy; SpDs: 1 L PEG at 21:00 the day before, 2 L PEG 4-6 h before colonoscopy | 159/159 | 1-d LRD | Not described | OBPS | 2-4 h | 3 | No |

| Shah et al[17], 2014 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Patients ≥ 18 yr | SSD: 2 L PEG at 5:00-7:00; SpDs: 1 L PEG at 18:00-19:00 the day before, 1 L PEG at 6:00-7:00 | 103/97 | 1-d liquid diet and CLD after midnight | 11:00-16:00 | OBPS | ≥ 4 h | 5 | No |

| Tellez-Avila et al[18], 2014 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Inpatients ≥ 18 yr | SSD: 2 L PEG at 6:00-8:00; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 17:00-19:00 the day before, 2 L PEG at 6:00-8:00 | 61/67 | Not described | Not described | BBPS | ≥ 3 h | 5 | No |

| Kotwal et al[19], 2014 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Inpatients 18-80 yr | SSD: 4 L PEG at 5:00-9:00; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 19:00-21:00 the day before, 2 L PEG at 7:00-9:00 | 60/60 | 1-d CLD | After 11:00 | OBPS | ≥ 2 h | 5 | No |

| Kim et al[20], 2014 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients 18-75 yr | SSD: 4 L PEG 6 h before colonoscopy; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 18:00 the day before, 2 L PEG 4-6 h before colonoscopy | 50/50 | Avoid high-fiber foods 3 d prior | Not described | OBPS | Not described | 2 | No |

| Seo et al[21], 2013 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients 18-85 yr | SSD: 2 L PEG 5 h before colonoscopy; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 18:00 the day before, 2 L PEG 5 h before colonoscopy | 103/102 | 3-d LRD | 9:00-17:00 | OBPS | ≥ 3 h | 5 | No |

| Cesaro et al[22], 2013 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients 18-85 yr | SSD: 2 L PEG-CS at 6:00 + bis 10-20 mg at 22:00 the day before; SpDs: 3 L PEG at 19:00 the day before, 1 L PEG at 7:00 | 50/51 | 3-d LRD | 11:00-18:00 | OBPS | Not described | 5 | Bisacodyl |

| Kwon et al[23], 2016 | Multicenter, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients ≥ 18 yr | SSD: 1 L PEG-ASc + 0.5 L water at 6:00, 20 mg bis + 0.5 L water at 20:00 the day before; SpDs: 1 L PEG-ASc + 0.5 L water at 20:00 the day before, 1 L PEG-ASc + 0.5 L water at 6:00 | 92/97 | LFF for 3 d, soft meal on the day prior | Not described | BBPS | ≥ 3 h | 5 | Bisacodyl |

| Kang et al[24], 2017 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients 20-75 yr | SSD: 1 L PEG-ASc 4 h before colonoscopy + 1 L water, 10 mg bis at 21:00 the day before; SpDs: 1 L PEG-ASc at 20:00 the day before + 0.5 L water, 1 L PEG-ASc 4 h before colonoscopy + 0.5 L water | 100/100 | 3-d LRD | 9:00-13:00 | BBPS | > 2 h | 3 | Bisacodyl |

| Choi et al[25], 2018 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Outpatient 18-80 yr | SSD: 1 L PEG-ASc 5 h before colonoscopy + 0.5 L water, Pru at 19:00 the day before + 0.5 L water; SpDs: 1 L PEG-ASc at 19:00 the day before + 0.5 L water, 1 L PEG-ASc 5 h before colonoscopy + 0.5 L water | 130/130 | 3-d LRD | 9:00-13:00 | BBPS | Not described | 5 | Prucalopride |

| Kim et al[26], 2019 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients 20-70 yr | SSD: 1L PEG-ASc at 5:00 + 1 L water + 20 mg bis; SpDs: 1 L PEG-ASc at 21:00 the day before + 0.5 L water, 1 L PEG-ASc at 5:00 + 0.5 L water | 83/85 | 1-d CLD | 8:30-12:00 | BBPS | Not described | 4 | Bisacodyl |

| Kim et al[27], 2020 | Single-center, single-blind, RCT | Patients 18-74 yr | SSD: 1 L PEG-ASc 5 h before endoscopy + 1 L water, 10 mg bis at 21:00 the day before; SpDs: 1 L PEG-ASc at 21:00 the day before + 0.5 L water, 1 L PEG-ASc 5 h before endoscopy + 0.5 L water | 99/99 | 3-d LRD | 9:00-17:00 | BBPS | Not described | 4 | Bisacodyl |

| de Leone et al[28], 2013 | Multicenter, single-blind, RCT | Outpatients 18-85 yr | SSD: 3-4 tablets bis at bedtime, 2 L PEG-CS 5 h before endoscopy; SpDs: 2 L PEG at 18:00 the day before, 2 L PEG 5 h before endoscopy | 78/79 | LFF for 3 d, CLD the day before | Morning | OBPS | Not described | 4 | Bisacodyl |

Bowel cleanliness was evaluated either with BBPS[11,12,14,15,18,23-27] or OBPS[13,16,17,19-22,28]. An adequate bowel preparation was defined as a total BBPS score ≥ 6 with all colon segments scores ≥ 2, or a total OBPS score < 5 (including score < 7 by De Leone, score ≤ 3 by Cesaro) or all colon segment OBPS score < 2. Diet restriction was mentioned in 16 trials and consisted of low residual diet/low-fiber foods[11,14-16,20-25,27-28] or clear liquid diet[13,15,17,19,26,28] before colonoscopy. Colonoscopy was performed with optimal preparation-to-colonoscopy (PC) interval time in only 6 trials[11,12,15,16,21,24], while 9 trials did not mention the PC interval[13,14,20,22,23,25-28].

Fourteen studies provided dichotomous information on adequate bowel preparation between the SSDs and SpDs groups, regardless of adjuvant laxative use, and significant heterogeneity was observed (P < 0.00001, I2 = 76%) in the pooled estimate. Using a random-effects model, no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups (RR = 0.97; 95%CI: 0.92-1.02) (P = 0.19) as shown in Figure 2.

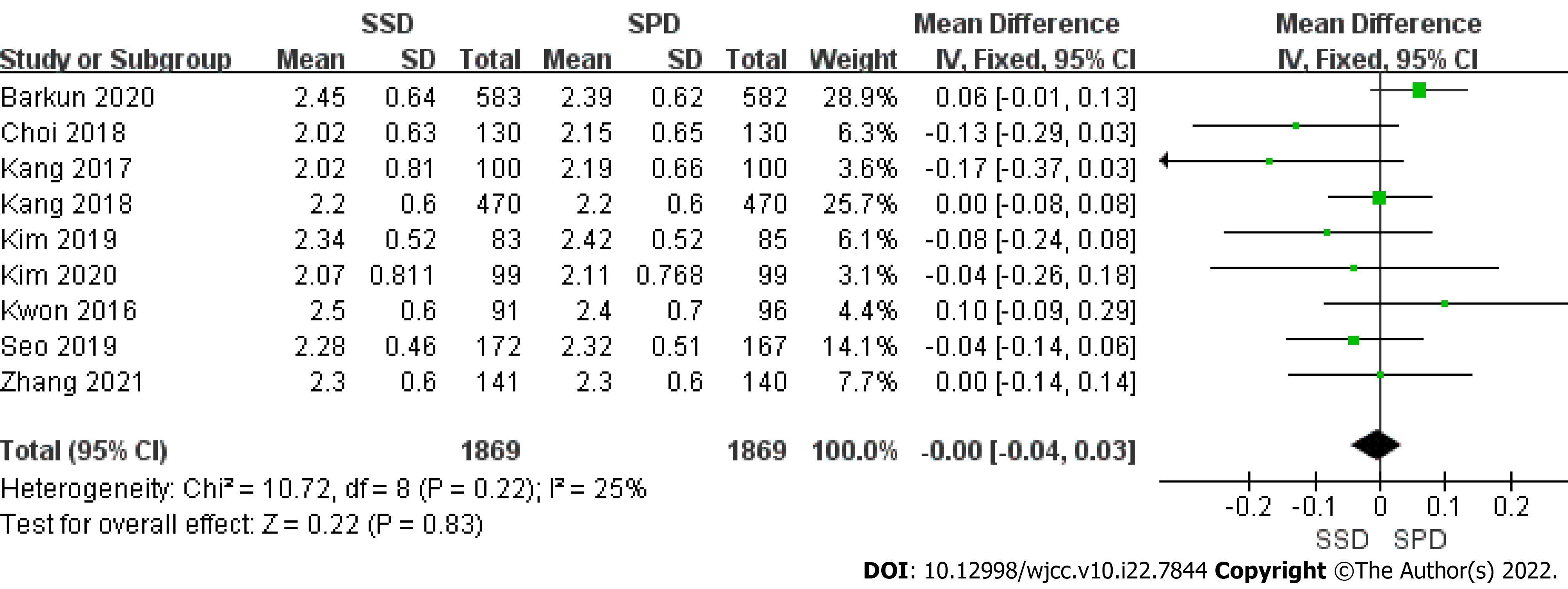

Continuous data on right colon BBPS was available in 9 trials (Figure 3). No significant heterogeneity was observed (P = 0.22, I2 = 25%). Using a fixed-effects model, we found that there was no significant difference between the two arms (MD = 0.00; 95%CI: -0.04, 0.03).

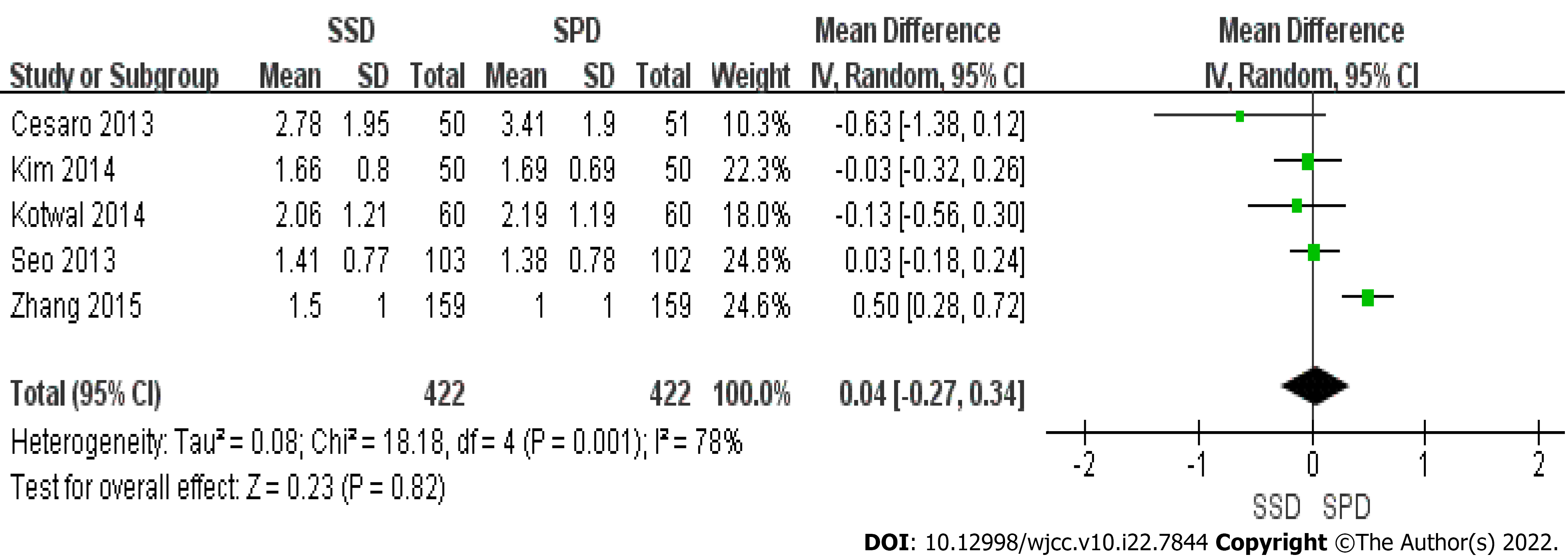

Five studies provided continuous data on right colon OBPS (Figure 4), and significant heterogeneity was observed (P = 0.001, I2 =78%). Using a random-effects model, no significant difference was found between the two arms (MD = 0.04; 95%CI: -0.27, 0.34) (P = 0.82).

2 L SSD with adjuvant vs SpDs: Seven trials provided dichotomous information on adequate bowel preparation comparing the 2 L SSDs with adjuvant laxative use to the (≥ 3 L) SpDs regimen. The pooled estimates showed significant heterogeneity within the included studies (P = 0.05, I2 = 51%). Using a random-effects model, no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups (RR = 1.00; 95%CI: 0.95, 1.05) (P = 0.99). Continuous data on the right colon BBPS was provided in 7 studies. Pooled estimate results showed no significant heterogeneity (P = 0.12, I2 = 41%). Using a fixed-effects model, we found that there was no significant difference between the two groups. (MD = 0.00; 95%CI: -0.05, 0.05) (P = 0.93). Only 1 study reported data on right colon OBPS (Table 2).

| Subgroup | Studies, n | SSD, n | SpDs, n | I2 , % | P value for heterogeneity | Pooled analysis (cat-RR/con-MD) | 95%CI | P value |

| 2 L SSD with adjuvant vs SpDs | ||||||||

| Adequate bowel preparation (categorical)[11,12,22,23,25,27,28] | 7 | 1172 | 1177 | 51 | 0.05 | 1.00 | (0.95, 1.05) | 0.99 |

| BBPS score for right colon (continuous)[11,12,23-27] | 7 | 1227 | 1232 | 41 | 0.12 | 0.00 | (-0.05, 0.05) | 0.93 |

| OBPS score for right colon (continuous)[22] | 1 | 50 | 51 | |||||

| 2 L SSD without adjuvant vs SpDs | ||||||||

| Adequate bowel preparation (categorical)[11,15,16,18,21] | 5 | 932 | 938 | 90 | < 0.00001 | 0.86 | (0.72, 1.02) | 0.07 |

| BBPS score for right colon (continuous)[11,15] | 2 | 611 | 610 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.00 | (-0.07, 0.07) | 1.00 |

| OBPS score for right colon (continuous)[16,21] | 2 | 262 | 261 | 89 | 0.003 | 0.26 | (-0.20, 0.72) | 0.26 |

| 4 L SSD without adjuvant vs SpDs | ||||||||

| Adequate bowel preparation (categorical)[13,14,20] | 3 | 364 | 375 | 0 | 0.66 | 0.99 | (0.94, 1.05) | 0.82 |

| BBPS score for right colon (continuous)[14] | 1 | 172 | 167 | |||||

| OBPS score for right colon (continuous)[19,20] | 2 | 110 | 110 | 0 | 0.71 | -0.06 | (-0.30, 0.18) | 0.62 |

2 L SSD without adjuvant vs SpDs: Five trials compared 2 L SSDs without adjuvant to ≥ 3 L SpDs regimens and provided categorical data on the adequacy of bowel preparation. The pooled estimate results showed significant heterogeneity within the included studies (P < 0.00001, I2 = 90%). Using a random-effects model, no statistical difference was reported between the two groups (RR = 0.86; 95%CI: 0.72, 1.02) (P = 0.07).

Two trials provided continuous data on right colon BBPS. The pooled estimates showed no significant heterogeneity between both studies (P = 1.00, I2 = 0%). Using a fixed-effects model, no significant difference was found between the two groups. (MD = 0.00; 95%CI: -0.07, 0.07) (P = 1.00). Two studies provided continuous data on right colon OBPS. The pooled estimates showed significant heterogeneity (P = 0.003, I2 = 89%). Using a random-effects model, no significant difference was found between the two groups. (MD = 0.26; 95%CI: -0.20, 0.72) (P = 0.26) (Table 2).

4 L SSD without adjuvant vs SpDs: Three trials compared the adequacy of bowel preparation between 4 L SSDs without adjuvant and 4 L SpDs regimens. The pooled estimates showed that no significant heterogeneity was present within these studies (P = 0.66, I2 = 0%). Using a fixed-effects model, we found that there was no significant difference between the two groups (RR = 0.99; 95%CI: 0.94, 1.05) (P = 0.82). Only 1 study reported data on the right colon BBPS.

The right colon OBPS scores were provided in 2 studies. The pooled estimates showed no significant heterogeneity between both studies (P = 0.71, I2 = 0%). Using a fixed-effects model, no significant difference was found between the two groups. (MD = -0.06; 95%CI: -0.30, 0.18) (P = 0.62) (Table 2).

Fifteen studies provided dichotomous information on sleep disturbance between the SSD and SpDs PEG groups (Table 3). During the pooled estimates, significant heterogeneity was observed (P < 0.00001, I2 = 74%). Using a random-effects model, a significant difference was found between the two groups (RR = 0.52; 95%CI: 0.40, 0.68) (P < 0.00001). During subgroup analysis, 7 trials comparing 2 L SSD with adjuvant vs SpDs showed no significant difference in sleep disturbance between the two groups (RR = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.43, 1.10) (P = 0.12).

| Secondary outcome | Studies (n) | SSD (n) | SpDs (n) | I2 (%) | P value for heterogeneity | Pooled analysis (cat-RR/con-MD) | 95%CI | P value |

| Sleep disturbance | 15 | 2591 | 2463 | 74 | < 0.00001 | 0.52 | (0.40, 0.68) | < 0.00001 |

| 2 L SSD with adjuvant vs SpDs | 7 | 1214 | 1215 | 69 | 0.003 | 0.69 | (0.43, 1.10) | 0.12 |

| 2 L SSD without adjuvant vs SpDs | 6 | 1014 | 1013 | 80 | 0.0002 | 0.45 | (0.30, 0.67) | < 0.0001 |

| 4 L SSD without adjuvant vs SpDs | 3 | 363 | 375 | 67 | 0.05 | 0.47 | (0.28, 0.78) | 0.004 |

| Willingness to repeat | 10 | 1996 | 1855 | 90 | < 0.00001 | 1.15 | (1.03, 1.29) | 0.01 |

| 2 L SSD with adjuvant vs SpDs | 6 | 1073 | 1078 | 89 | < 0.00001 | 1.24 | (1.06, 1.45) | 0.008 |

| 2 L SSD without adjuvant vs SpDs | 3 | 691 | 690 | 82 | 0.004 | 1.14 | (1.01, 1.29) | 0.03 |

| 4 L SSD without adjuvant vs SpDs | 2 | 232 | 227 | 54 | 0.14 | 0.89 | (0.71, 1.13) | 0.34 |

| Side effects | ||||||||

| Nausea | 17 | 2715 | 2592 | 68 | < 0.0001 | 0.95 | (0.78, 1.16) | 0.63 |

| Vomiting | 16 | 2644 | 2521 | 64 | 0.0002 | 0.96 | (0.66, 1.38) | 0.81 |

| Abdominal pain | 17 | 2715 | 2592 | 38 | 0.06 | 0.75 | (0,62, 0.90) | 0.002 |

| Bloating | 15 | 2205 | 2077 | 67 | 0.0001 | 0.80 | (0.63, 1.01) | 0.06 |

Ten trials provided dichotomous information on patient willingness to repeat the procedure using the same preparation between the SSD and SpDs PEG groups (Table 3). During the pooled estimates, significant heterogeneity was observed (P < 0.00001, I2 = 90%). Using a random-effects model, a significant difference was found between the two groups (RR=1.15; 95%CI: 1.03, 1.29) (P = 0.01). Two trials in subgroup analysis of 4 L SSD without adjuvant vs SpDs found no significant difference between the two groups (RR = 0.89; 95%CI: 0.71, 1.13) (P = 0.34).

The incidence of adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and bloating, was reported in 17, 16, 17 and 15 trials, respectively (Table 3). No significant difference in nausea (RR = 0.95; 95%CI: 0.78, 1.16), vomiting (RR = 0.96; 95%CI: 0.66, 1.38) and bloating (RR = 0.80; 95%CI: 0.63, 1.01) was found between the two groups. However, there was a significant difference in abdominal pain between the two arms, favoring the SSD group (RR = 0.75; 95%CI: 0.62, 0.90).

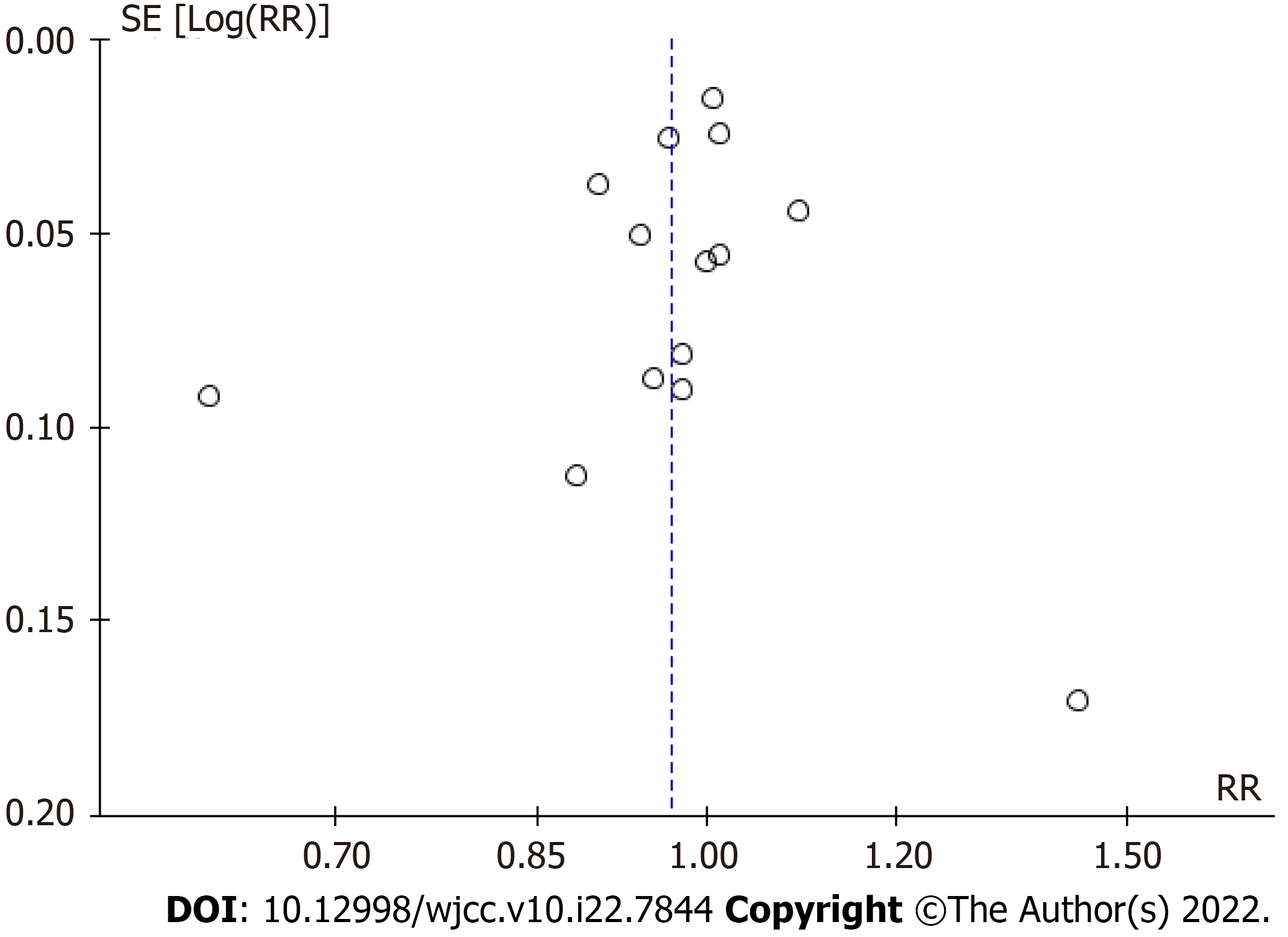

For the publication bias, in our meta-analysis a better symmetry was present with the use of funnel plots (Figure 5). The Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation as one systematic approach rated the certainty of evidence for moderate level in this systematic review and meta-analysis (Table 4).

| No. of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | SSD | SpDs | RR (95%CI) | Effect/Absolute | Quality | Importance |

| Adequate bowel cleanliness | ||||||||||||

| 14 | Randomized trials | No serious risk of bias | Serious1 | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 2002/2468 (81.1%) | 1973/2350 (84.0%) | RR 0.97 (0.92 to 1.02) | 25 fewer per 1000 (from 67 fewer to 17 more) | (+++) moderate | Critical |

| 85.5% | 26 fewer per 1000 (from 68 fewer to 17 more) | |||||||||||

| Right colon BBPS | ||||||||||||

| 9 | Randomized trials | No serious risk of bias | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 1869 | 1869 | - | Md 0 higher (0.04 lower to 0.03 higher) | (++++) high | Critical |

| Right colon OBPS | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Randomized trials | No serious risk of bias | Serious1 | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 422 | 422 | - | Md 0.04 higher (0.27 lower to 0.34 higher) | (+++) moderate | Critical |

| Sleep disturbance | ||||||||||||

| 15 | Randomized trials | No serious risk of bias | Serious1 | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 348/2591 (13.4%) | 651/2463 (26.4%) | RR 0.52 (0.40 to 0.68) | 127 fewer per 1000 (from 85 fewer to 159 fewer) | (+++) moderate | Critical |

| 32.0% | 154 fewer per 1000 (from 102 fewer to 192 fewer) | |||||||||||

| Willingness to repeat | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Randomized trials | No serious risk of bias | Serious1 | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 1624/1996 (81.4%) | 1269/1855 (68.4%) | RR 1.15 (1.03 to 1.29) | 103 more per 1000 (from 21 more to 198 more) | (+++) moderate | Critical |

| 65.2% | 98 more per 1000 (from 20 more to 189 more) | |||||||||||

| Nausea | ||||||||||||

| 17 | Randomized trials | No serious risk of bias | Serious1 | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 516/2715 (19.0%) | 559/2592 (21.6%) | RR 0.95 (0.78 to 1.16) | 11 fewer per 1000 (from 47 fewer to 35 more) | (+++) moderate | Critical |

| 20.0% | 10 fewer per 1000 (from 44 fewer to 32 more) | |||||||||||

| Vomiting | ||||||||||||

| 16 | Randomized trials | No serious risk of bias | Serious1 | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 191/2644 (7.2%) | 202/2521 (8.0%) | RR 0.96 (0.66 to 1.38) | 3 fewer per 1000 (from 27 fewer to 30 more) | (+++) moderate | Critical |

| 7.2% | 3 fewer per 1000 (from 24 fewer to 27 more) | |||||||||||

| Abdominal pain | ||||||||||||

| 17 | Randomized trials | No serious risk of bias | Serious1 | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 168/2715 (6.2%) | 221/2592 (8.5%) | RR 0.75 (0.62 to 0.9) | 21 fewer per 1000 (from 9 fewer to 32 fewer) | (+++) moderate | Critical |

| 8.2% | 20 fewer per 1000 (from 8 fewer to 31 fewer) | |||||||||||

| Bloating | ||||||||||||

| 15 | Randomized trials | No serious risk of bias | Serious1 | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 322/2205 (14.6%) | 415/2077 (20.0%) | RR 0.8 (0.63 to 1.01) | 40 fewer per 1000 (from 74 fewer to 2 more) | (+++) moderate | Critical |

| 18.4% | 37 fewer per 1000 (from 68 fewer to 2 more) | |||||||||||

This updated meta-analysis reviewed 18 trials comparing the efficacy and tolerability of bowel preparation between SSD PEG-based and large-volume SpDs PEG regimens. In recent years, the split dose of 4 L PEG has been adopted as a standard regimen for bowel preparation. However, patients often complain of the large-volume regimen and sleep disturbance due to frequent bowel movements and abdominal discomfort. To enhance patient compliance with the preparation, several studies have suggested adding other laxatives, such as bisacodyl, linaclotide or prucalopride, to a low-volume PEG bowel preparation to reduce the solution volume[11,12,25]. In the present study, according to the volume of PEG ingested and combination with adjuvant laxative, SSD PEG-based regimens were separated into three subgroups: low-volume (2 L) SSD PEG combined with an adjuvant agent, low-volume (2 L) SSD PEG without adjuvant laxative and large-volume (4 L) SSD PEG without adjuvant laxative. In a pooled analysis, we have shown that SSD PEG was as effective as SpDs PEG-based regimens in terms of bowel cleanliness, regardless of adjuvant laxative use and dosage.

Previous meta-analyses by Cheng et al[29] and Avalos et al[30] showed a trend to the equivalent efficacy for bowel preparation in terms of bowel cleanliness and adenoma detection rate when compared to same-day (one or two doses) with split-dose bowel preparation regimens regardless of purgative type. Patients with a history of pelvic surgery and colorectal surgery as high-risks of poor bowel preparation were not excluded by the forementioned studies[29,30]. Other identified patient-related risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation include diabetes and constipation[31]. In the present study, patients with a history of constipation and diabetes mellitus were included, and analysis results obtained were consistent with previous studies. We considered that the SSD PEG-based arm had the same efficacy in bowel cleanliness as the SpDs arm for patients at high-risk of poor bowel preparation by complying with the optimal PC interval and diet instruction before colonoscopy.

In a study by Seo et al[3], multivariate analysis showed that the PC interval, the amount of PEG ingested and compliance with diet instructions were significant contributors to satisfactory bowel preparation, regardless of when the procedure was performed during the day. Colonoscopies performed with a PC interval of 3 to 5 h had the best bowel-cleansing quality throughout the colon, while a PC interval of 3 to 7 h was an acceptable scale for bowel preparation. It has been reported that after the optimal time window, small-bowel contents of bubbles and viscous bile-stained mucous are evacuated into the colon and restrict the visibility of the colonic mucosa, especially in the right colon. Small flat lesions that are difficult to identify in the right colon can easily be missed by the endoscopist if concealed by opaque small bowel effluent. Accordingly, same-day preparation with split-doses and full-doses improves bowel cleansing and increases the detection rate of small adenomas[28].

Compliance with dietary instructions has been documented as another factor affecting the quality of bowel preparation. A meta-analysis by Chen et al[32] that analyzed factors of inadequate bowel preparation found no significant difference between a low residual diet and a clear liquid diet the day before colonoscopy. In our meta-analysis, in all included trials, patients in both arms followed a low residual diet or clear liquid diet, and no heterogeneity was found for dietary restriction before colonoscopy.

Consistent with a study by Avalos et al[30] we found that significantly less sleep disturbance was associated with the SSD PEG-based regimens without adjuvant laxatives than the SpDs PEG. However, the incidence of sleep disturbance in combination regimens of low-volume (2 L) SSD with an adjuvant laxative (bisacodyl, linaclotide or prucalopride) was comparable with SpDs regimens. It was noted that bowel movements induced by bisacodyl taken on the night before colonoscopy occurred after waking up. De Leone et al[28] suggested that sleeping difficulties were more likely to be attributed to the anxiety for the day-after procedure rather than nocturnal awakenings for defecation or abdominal pain in patients who took the combination regimen consisting of low-volume PEG with bisacodyl. Based on these findings, we conclude that the split-dose regimen taken the night before colonoscopy and anxiety for the procedure play an important role in the sleep quality of patients.

Patient tolerance of bowel preparation regimens mainly depends on sleep disruptions and adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain/cramping and bloating. Significantly less nocturnal awakenings for defecation were reported in the SSD PEG-based arm than other SpDs PEG regimens, and no significant difference in other adverse effects was found. Given the low incidence of sleep disturbance and abdominal pain, patients were more tolerant to the SSD PEG-based arm for bowel preparation.

Moreover, patients who received the low-volume (2 L) SSD PEG regimens exhibited increased willingness to repeat the procedure using the same preparation. However, the large-volume (4 L) SSD PEG arm was not superior to the SpDs regimens in terms of willingness to repeat the procedure using the same preparation. This finding suggested that patient intolerance to ingestion of large volumes over a short period was a significant factor contributing to non-compliance and decreased willingness to repeat the procedure with the same regimen.

There are several advantages to this meta-analysis. We performed the extensive retrieval strategy and included only randomized controlled trials. Other advantages were related to the quality of the included studies and to the publication bias. The methodological quality assessment of the included studies was moderate to high according to the Cochrane risk of bias tool and modified Jadad score. For the publication bias, in our meta-analysis a rough symmetry was present with the use of funnel plots and the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach.

This meta-analysis has several limitations. First, we enrolled only adult patients and excluded those who had undergone colorectal surgery and/or bowel obstruction; accordingly, the findings of our meta-analysis cannot be generalized for all patients that undergo colonoscopy. Moreover, it is widely acknowledged that constipation is a high-risk factor for poor preparation; however, there was a certain level of inconsistency on the proportion and severity of constipation within the included studies. Furthermore, adenoma detection rate was not evaluated as a secondary outcome. Indeed, adenoma detection rate is a quality indicator for colonoscopy and can be influenced by the endoscopist’s level of expertise and the quality of the bowel preparation[33].

We found that the SSD regimens of PEG were non-inferior to large-volume (≥ 3 L) SpDs PEG in terms of bowel cleanliness. Better tolerance to SSD PEG was accounted for by less sleep disturbance and abdominal pain than with the SpDs regimens. Given its efficacy and tolerability, the low-volume (2 L) SSD PEG regimen has huge prospects as a superior alternative to SpDs regimens as long as the optimal PC interval and dietary instructions for bowel preparation are respected.

High volume (4 L) split-dose regimens (SpDs) of polyethylene glycol (PEG) have been recommended as the gold-standard regimen for bowel preparation, but its large volume of fluids and poor tolerability have become sources of patient dissatisfaction.

The same-day single-dose (SSD) PEG has been recommended as an alternative for bowel preparation. However, its superiority compared to other regimens is a matter of debate.

To seek one PEG-based regimen for bowel preparation with characteristics of equal cleansing efficacy, reducing the preparation volume and improving patient tolerance.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and tolerability of SSD PEG-based arm vs large-volume (≥ 3 L) SpDs PEG solutions for bowel preparation before colonoscopy, regardless of adjuvant laxative use.

A total of 18 studies were included. There was no statistically significant difference of adequate bowel preparation, right colon Boston Bowel Preparation Scale and right colon Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scale between (2 L/4 L) SSDs and large-volume (4 L/3 L) SpDs, regardless of adjuvant laxative use. The use of SSDs had advantages of less sleep disturbance and lower incidence of abdominal pain. Patients that received low-volume (2 L) SSDs showed more willingness to repeat the procedure than patients receiving SpDs (P < 0.05).

Regardless of adjuvant laxative use, the (2 L/4 L) SSDs PEG-based arm was considered equal or better than the large-volume (≥ 3 L) SpDs PEG regimen in terms of bowel cleanliness and tolerability.

Given its efficacy and tolerability, the low-volume (2 L) SSD PEG regimen has huge prospects as a superior alternative to SpDs regimens as long as the optimal preparation-to-colonoscopy interval and dietary instructions for bowel preparation are respected.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: El-Nakeep S, Egypt; Watanabe J, Japan S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Chung YW, Han DS, Park KH, Kim KO, Park CH, Hahn T, Yoo KS, Park SH, Kim JH, Park CK. Patient factors predictive of inadequate bowel preparation using polyethylene glycol: a prospective study in Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:448-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nguyen DL, Wieland M. Risk factors predictive of poor quality preparation during average risk colonoscopy screening: the importance of health literacy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:369-372. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Seo EH, Kim TO, Park MJ, Joo HR, Heo NY, Park J, Park SH, Yang SY, Moon YS. Optimal preparation-to-colonoscopy interval in split-dose PEG bowel preparation determines satisfactory bowel preparation quality: an observational prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF, Early DS, Muthusamy VR, Khashab MA, Chathadi KV, Fanelli RD, Chandrasekhara V, Lightdale JR, Fonkalsrud L, Shergill AK, Hwang JH, Decker GA, Jue TL, Sharaf R, Fisher DA, Evans JA, Foley K, Shaukat A, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Wang A, Acosta RD. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:781-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hassan C, Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, Polkowski M, Rembacken B, Saunders B, Benamouzig R, Holme O, Green S, Kuiper T, Marmo R, Omar M, Petruzziello L, Spada C, Zullo A, Dumonceau JM; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2013;45:142-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Moon W. Optimal and safe bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:219-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lim YJ, Hong SJ. What is the best strategy for successful bowel preparation under special conditions? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2741-2745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Enestvedt BK, Tofani C, Laine LA, Tierney A, Fennerty MB. 4-Liter split-dose polyethylene glycol is superior to other bowel preparations, based on systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1225-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rostom A, Jolicoeur E. Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:482-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 925] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang M, Zou W, Xu C, Jia R, Liu K, Xu Q, Xu H. Polyethylene glycol combined with linaclotide is an effective and well-tolerated bowel preparation regimen for colonoscopy: an endoscopist-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Barkun AN, Martel M, Epstein IL, Hallé P, Hilsden RJ, James PD, Rostom A, Sey M, Singh H, Sultanian R, Telford JJ, von Renteln D. The Bowel CLEANsing National Initiative: A Low-Volume Same-Day Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Preparation vs Low-Volume Split-Dose PEG With Bisacodyl or High-Volume Split-Dose PEG Preparations-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:2068-2076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Castro FJ, Al-Khairi B, Singh H, Mohameden M, Tandon K, Lopez R. Randomized Controlled Trial: Split-dose and Same-day Large Volume Bowel Preparation for Afternoon Colonoscopy Have Similar Quality of Preparation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:724-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Seo M, Gweon TG, Huh CW, Ji JS, Choi H. Comparison of Bowel Cleansing Efficacy, Safety, Bowel Movement Kinetics, and Patient Tolerability of Same-Day and Split-Dose Bowel Preparation Using 4 L of Polyethylene Glycol: A Prospective Randomized Study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:1518-1527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kang X, Zhao L, Zhu Z, Leung F, Wang L, Wang X, Luo H, Zhang L, Dong T, Li P, Chen Z, Ren G, Jia H, Guo X, Pan Y, Fan D. Same-Day Single Dose of 2 Liter Polyethylene Glycol is Not Inferior to The Standard Bowel Preparation Regimen in Low-Risk Patients: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:601-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang S, Li M, Zhao Y, Lv T, Shu Q, Zhi F, Cui Y, Chen M. 3-L split-dose is superior to 2-L polyethylene glycol in bowel cleansing in Chinese population: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shah H, Desai D, Samant H, Davavala S, Joshi A, Gupta T, Abraham P. Comparison of split-dosing vs non-split (morning) dosing regimen for assessment of quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:606-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Téllez-Ávila FI, Murcio-Pérez E, Saúl A, Herrera-Gómez S, Valdovinos-Andraca F, Acosta-Nava V, Barreto R, Elizondo-Rivera J. Efficacy and tolerability of low-volume (2 L) vs single- (4 L) vs split-dose (2 L + 2 L) polyethylene glycol bowel preparation for colonoscopy: randomized clinical trial. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:731-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kotwal VS, Attar BM, Carballo MD, Lee SS, Kaura T, Go B, Zhang H, Trick WE. Morning-only polyethylene glycol is noninferior but less preferred by hospitalized patients as compared with split-dose bowel preparation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:414-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Kim ES, Lee WJ, Jeen YT, Choi HS, Keum B, Seo YS, Chun HJ, Lee HS, Um SH, Kim CD, Ryu HS. A randomized, endoscopist-blinded, prospective trial to compare the preference and efficacy of four bowel-cleansing regimens for colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:871-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Seo EH, Kim TO, Park MJ, Heo NY, Park J, Yang SY. Low-volume morning-only polyethylene glycol with specially designed test meals vs standard-volume split-dose polyethylene glycol with standard diet for colonoscopy: a prospective, randomized trial. Digestion. 2013;88:110-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cesaro P, Hassan C, Spada C, Petruzziello L, Vitale G, Costamagna G. A new low-volume isosmotic polyethylene glycol solution plus bisacodyl vs split-dose 4 L polyethylene glycol for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy: a randomised controlled trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:23-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kwon JE, Lee JW, Im JP, Kim JW, Kim SH, Koh SJ, Kim BG, Lee KL, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC. Comparable Efficacy of a 1-L PEG and Ascorbic Acid Solution Administered with Bisacodyl vs a 2-L PEG and Ascorbic Acid Solution for Colonoscopy Preparation: A Prospective, Randomized and Investigator-Blinded Trial. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kang SH, Jeen YT, Lee JH, Yoo IK, Lee JM, Kim SH, Choi HS, Kim ES, Keum B, Lee HS, Chun HJ, Kim CD. Comparison of a split-dose bowel preparation with 2 Liters of polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid and 1 Liter of polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid and bisacodyl before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:343-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Choi SJ, Kim ES, Choi BK, Min G, Kim W, Lee JM, Kim SH, Choi HS, Keum B, Jeen YT, Lee HS, Chun HJ, Kim CD. A randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of 1-L polyethylene glycol solution with ascorbic acid plus prucalopride vs 2-L polyethylene glycol solution with ascorbic acid for bowel preparation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1619-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim SH, Kim ER, Kim K, Kim TJ, Hong SN, Chang DK, Kim YH. Combination of bisacodyl suppository and 1 L polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid is a non-inferior and comfortable regimen compared to 2 L polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:600-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kim SH, Kim JH, Keum B, Jeon HJ, Jang SH, Choi SJ, Kim SH, Lee JM, Choi HS, Kim ES, Jeen YT, Lee HS, Chun HJ, Kim CD. A Randomized, Endoscopist-Blinded, Prospective Trial to Compare the Efficacy and Patient Tolerability between Bowel Preparation Protocols Using Sodium Picosulfate Magnesium Citrate and Polyethylene-Glycol (1L and 2L) for Colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:9548171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | de Leone A, Tamayo D, Fiori G, Ravizza D, Trovato C, De Roberto G, Fazzini L, Dal Fante M, Crosta C. Same-day 2-L PEG-citrate-simethicone plus bisacodyl vs split 4-L PEG: Bowel cleansing for late-morning colonoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:433-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cheng YL, Huang KW, Liao WC, Luo JC, Lan KH, Su CW, Wang YJ, Hou MC. Same-day Versus Split-dose Bowel Preparation Before Colonoscopy: A Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52:392-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Avalos DJ, Castro FJ, Zuckerman MJ, Keihanian T, Berry AC, Nutter B, Sussman DA. Bowel Preparations Administered the Morning of Colonoscopy Provide Similar Efficacy to a Split Dose Regimen: A Meta Analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52:859-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, Robertson DJ, Boland CR, Giardello FM, Lieberman DA, Levin TR, Rex DK; US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:903-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chen E, Chen L, Wang F, Zhang W, Cai X, Cao G. Low-residue vs clear liquid diet before colonoscopy: An updated meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e23541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zwierko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in RCA: 1468] [Article Influence: 97.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |