Published online Aug 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i22.7785

Peer-review started: March 5, 2022

First decision: April 11, 2022

Revised: April 18, 2022

Accepted: June 18, 2022

Article in press: June 18, 2022

Published online: August 6, 2022

Processing time: 138 Days and 21.2 Hours

Conventional endoscopic papillectomy (EP) is safe and effective for the treatment of small papilla adenoma to even large laterally spreading tumors of duodenum lesions. As reported by some existing studies, temporarily placing a prophylactic stent in the pancreatic and bile duct can lower the risk of this perioperative complication.

To evaluate the usefulness, convenience, safety, and short-term results of a novel autorelease bile duct supporter after EP procedure, especially the effectiveness in preventing EP.

A single-center comparison study was conducted to verify the feasibility of the novel method. After EP, a metallic endoclip and human fibrin sealant kit were applied for protection. The autorelease bile duct supporter fell into the duct segment and the intestinal segment. Specifically, the intestinal segment was extended by nearly 5 cm as a bent coil. The bile was isolated from the pancreatic juice using an autorelease bile duct supporter, which protected the wound surface. The autorelease bile duct supporter fell off naturally and arrived in colon nearly 10 d after the operation.

En bloc endoscopic resection was performed in 6/8 patients (75%), and piecemeal resection was performed in 2/8 of patients (25%). None of the above patients were positive for neoplastic lymph nodes or distant metastasis. No cases of mortality, hemorrhage, delayed perforation, pancreatitis, cholangitis or duct stenosis with the conventional medical treatment were reported. The autorelease bile duct supporter in 7 of 8 patients fell off naturally and arrived in colon 10 d after the operation. One autorelease bile duct supporter was successfully removed using forceps or snare under endoscopy. No recurrence was identified during the 8-mo (ranging from 6-9 mo) follow-up period.

In brief, it was found that the autorelease bile duct supporter could decrease the frequency of procedure-associated complications without second endoscopic retraction. Secure closure of the resection wound with clips and fibrin glue were indicated to be promising and important for the use of autorelease bile duct supporters. Well-designed larger-scale comparative studies are required to confirm the findings of this study.

Core Tip: In this study, a novel autorelease bile duct supporter was successfully inserted through a guide wire using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in all patients after endoscopic papillectomy, during which an experienced operator was required for the insertion of the guide wire. The novel autorelease bile supporter entered the colon nearly 10 d after the endoscopic procedure with automatic shedding characteristics and decreased the frequency of procedure-related complications without a second endoscopic retraction.

- Citation: Liu SZ, Chai NL, Li HK, Feng XX, Zhai YQ, Wang NJ, Gao Y, Gao F, Wang SS, Linghu EQ. Prospective single-center feasible study of innovative autorelease bile duct supporter to delay adverse events after endoscopic papillectomy. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(22): 7785-7793

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i22/7785.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i22.7785

Endoscopic sphincterotomy was first reported in 1981 as an endoscopic operative strategy for the treatment of ampullary tumors[1]. Conventional endoscopic papillectomy (EP) has been indicated to be safe and effective for small papilla adenoma (PA) to even large laterally spreading tumor (LST) of duodenum lesions[2]. The above lesions potentially undergoing the adenoma-carcinoma sequence are expected to be removed by endoscopy resection for curative therapy[3,4]. Compared with surgical management by either pancreaticoduodenectomy or duodenostomy, EP using a snare has less mor

Before proceeding with attempted endoscopic resection, biopsy specimens from suspicious ampullary lesions are recommended and should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis and exclude carcinoid tumors or gangliocytic paragangliomas[6]. EP has been found to be effective and safe for experienced hands with success rates of nearly 80% for lesions benign ampullary adenoma, HGIN, and noninvasive cancer without intraductal tumor growth[7,8]. Ductography by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with bile and pancreatic duct plays a vital role in the evaluation of any ampullary adenomas ductal extension. En bloc resection should be performed by endoscopic snares, because of its advantages of short procedure time, less cautery and complete tissue sample for pathology evaluation. EP is correlated with an increased risk of procedure-related acute pancreatitis.

As reported by several studies, temporarily placing a prophylactic stent in the pancreatic and bile duct can lower the risk of this perioperative complication[9,10]. To date, no clear consensus relating to the parameter of pancreatic and bile duct stents has been reached.

This study assessed the usefulness, convenience, safety, and short-term results of a novel autorelease bile duct supporter after EP procedure, especially the effectiveness in preventing EP-related adverse events.

In general, 8 patients were diagnosed histopathologically with PA and duodenum LST between March 2021 and September 2021 in the gastroenterology endoscopy center of Chinese PLA General Hospital (Beijing, China). All patients received abdominal computed tomography (CT) and pathological biopsy in before EP to evaluate the invasion depth. Exclusion criteria included suggestion of malignancy by pathological biopsy and suspicion of invasion into the pancreaticobiliary duct. Patients were sedated with a balanced propofol and maintained sedation with initial intravenous administration of midazolam. Carbon dioxide insufflation was conducted, and prophylactic antibiotics were permitted.

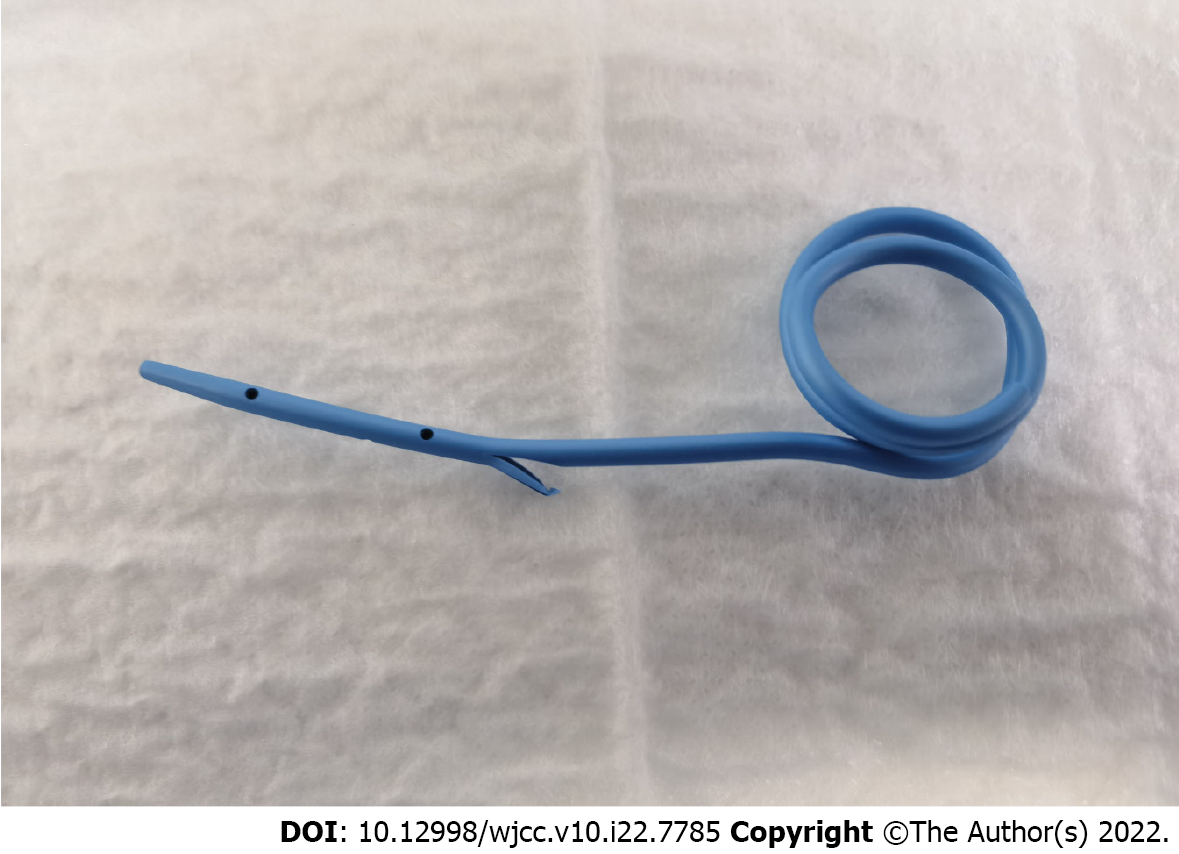

The procedure of EP in combination with this novel autorelease bile duct supporter is described in Figure 1. A submucosal injection with 1:10000 diluted epinephrine into the submucosa at 3 to 4 locations around the ampulla was performed to evaluate the lesion. Electrosurgical snare (SD-7P-1/SD-221L-25; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) passed over the working channel of the duodenoscope. The snare was carefully deployed around the ampullary lesion, and it grasped all abnormal-appearing mucosal tissues. En bloc or piecemeal resection of the lesion was performed based on the “Forced Coag” mode and “Endocut” mode (VIO 300D; Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany), and any suspicious residual lesion after resection was ignited through argon plasma coagulation. Electric coagulation forceps were employed for hemostasis when required. The resected specimen was retrieved with either the snare or a grasper. A guidewire was inserted though the catheter into the bile duct. The wound was closed with endoscopic hemoclips. The autorelease bile duct supporter involved the duct segment and the intestinal segment, in which the intestinal segment was extended by nearly 5 cm as a bent coil. The novel autorelease bile duct supporter was inserted through a guide wire using ERCP (Figure 2) to ensure adequate pancreatobiliary drainage. The gravity of the curved coil of autorelease bile stent could ensure the automatic shedding characteristics of this novel bile duct supporter. Fibrin glue (S10959931; Human Fibrinogen, Shanghai, China) was sprayed on the wound. The resected specimen was sent immediately for histopathologic analysis through serial sectioning. The autorelease bile duct supporter fell off naturally and arrived in colon nearly 10 d after the operation.

Stent placement were rechecked under X-radiography. Fasting water, acid-inhibitory drugs, enzyme inhibitors (somatostatin), and total parenteral nutrition were given through intravenous infusion nearly 10 d after the operation. The autorelease bile duct supporter fell off naturally and arrived in colon about 10 d after the operation based on X-ray image examination.

Early complications (e.g., bleeding, perforation and acute pancreatitis) after the procedure were controlled by hot-biopsy forceps (Coagrasper; Olympus) hemoclips and somatostatin. Post-EP pancreatitis was set as a 3-fold increase in pancreatic enzymes with abdominal pain[7].

Perforation was recognized as a transmural defect by emergency gastroscopy or radiographic evidence of free retroperitoneal or intraperitoneal air by CT scan. Endoscopic success was defined as complete resection of the lesion without any residual tumor tissue, as well as when no recurrence was detected at the 3-mo and 6-mo follow-up after EP. The resection rate of the tumor, discharge of the autorelease stent, operative time, early complications, late complications and tumor recurrence were predicted.

Table 1 lists the clinicopathological data and outcomes of 2 women and 6 men. The mean age was 55.5 ± 4.9 years. The size of adenomas ranged from 20-43 mm with mean (standard deviation) 28.1 mm. Preoperative pathological diagnosis was tubular adenoma in 3, tubulovillous adenoma with low-grade dysplasia in 1, as well as tubulovillous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia (HGD), HGD/inflammation, and neuroendocrine tumor in 2, 1, in 1, respectively (Table 1).

| No. | Sex | Age in yr | Tumor size in mm | Biopsy pathology |

| 1 | M | 59 | 20 | Tubular adenoma |

| 2 | M | 60 | 15 | Tubular adenoma and HGD |

| 3 | M | 49 | 32 | Adenomatoid hyperplasia and LGD |

| 4 | M | 44 | 20 | Tubular adenoma |

| 5 | M | 50 | 10 | Neuroendocrine tumor (stage G1) |

| 6 | F | 86 | 40 | HGD |

| 7 | M | 56 | 43 | Tubular adenoma and HGD |

| 8 | F | 52 | 20 | Tubular adenoma |

The median tumor area of the tumors was measured as 7.57 mm2 (ranging from 4.7-11.6 mm2). All PA with positive lifting sign after submucous injection was considered a criterion of lower superficial invasion. The resection was histopathologically performed in all patients. En bloc endoscopic resection was performed in 6/8 patients (75%), and piecemeal resection was performed in 2/8 of patients (25%). After EP, the autorelease bile duct supporter was placed. The average operation time was recorded as 47.1 ± 6.7 min. Tumor was confined to the mucosal layer in 5 cases and invaded the submucosa in 2 cases. In 1 case, tumor invaded the muscularis mucosa. None of the above patients were reported to be positive for neoplastic lymph nodes or distant metastasis.

There was only 1 case with positive lateral margin lesion after EP, and no treatment was added, except for endoscopic follow-up. The final histopathological diagnoses of the endoscopic specimens consisted of 3 cases of tubular adenoma, 3 cases of tubulovillous adenoma, 1 case of hamartomatous polyp, 1 case of adenocarcinoma, and 1 case of atypical juvenile polyposis with tubulovillous adenoma (Table 2). Among the 3 cases of tubular adenomas, 2 were correlated with HGD, in which the depth of invasion was limited to the mucosa. In the 3 cases of tubulovillous adenoma, HGD was found with submucosa invasion. The case of neuroendocrine tumor was confirmed to be G2 stage based on pathologically immunohistochemical staining. 1 patient had postoperative abdominal pain, which was resolved with antibiotic and somatostatin.

| No. | Tumor size in mm2 | Lifting sign | Operation time in min | En bloc or piecemeal | Autorelease at 2 wk | Complications | R0 resection | Depth of invasion | Lesion pathology |

| 1 | 5.495 | (+) | 11 | En bloc | (+) | (-) | (+) | Mucosa | Tubulovillous adenoma/HGD |

| 2 | 8.635 | (+) | 27 | En bloc | (-) | (-) | (-) | Submucosa | Tubulovillous adenoma/HGD |

| 3 | 9.734 | (+) | 21 | En bloc | (+) | (-) | (+) | Mucosa | Adenomatoid hyperplasia/LGD |

| 4 | 6.28 | (+) | 8 | En bloc | (+) | (-) | (+) | Mucosa | Tubular adenoma |

| 5 | 4.71 | (+) | 16 | En bloc | (+) | (-) | (+) | Mucosa | Neuroendocrine tumor, stage G2 |

| 6 | 9.42 | (+) | 25 | Piecemeal | (+) | (-) | (+) | Muscularis mucosa | Tubular adenoma/HGD |

| 7 | 11.618 | (+) | 16 | Piecemeal | (+) | (-) | (+) | Submucosa | Tubulovillous adenoma/HGD |

| 8 | 4.71 | (+) | 13 | En bloc | (+) | (-) | (+) | Mucosa | Tubular adenoma/LGD |

All cases were reported without any mortality, hemorrhage, delayed perforation, pancreatitis, cholangitis or duct stenosis with conventional medical treatment. The autorelease bile duct supporter in 7 of 8 patients fell off naturally and arrived in colon 10 d after the operation. One of this autorelease bile duct supporter was successfully removed with forceps or snare under endoscopy.

This neuroendocrine patient was referred for surgery and received pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy after multidisciplinary diagnosis and treatment. No recurrence was identified during the 8-mo (ranging from 6-9 mo) follow-up.

With a thin, highly vascular wall, the major papilla refers to the site of the confluence of the pancreatic and bile duct orifices, which can increase the risk of bleeding, pancreatitis, perforation and other complications after EP[11]. In this study, 8 patients with ampullary adenoma were treated with an autorelease bile duct supporter to investigate the parameters that might define this novel stent without second endoscopic retraction as an effective method. Adenoma of the major duodenal papilla is recognized as a type of benign lesion that requires complete resection for the potential premalignant in patients with reasonable life expectancy[12]. Compared with traditionally surgical segmental or whipple resection, EP exhibits significant advantages in reducing complications (e.g., acute pancreatitis, bleeding and perforation), attendant cost, morbidity, as well as potential mortality risk[2,13]. The overall reported incidence of complication rate changed from 0.4% to 7.9% for bleeding, perforation, cholangitis and pancreatitis[14].

Some closing and covering methods were employed to avoid the exposure of digestive juices for the mitigation of the delayed complications (e.g., clips and stents). Proper closure of the mucosal with clips and fibrin glue could mitigate the complication and improve the EP outcomes[15,16]. Poor operability of clips under duodenoscope after papilla resection might be technically challenging to extend the lesion fully and perform appropriate suturing, whereas we still strongly recommend adopting endoscopic clips to suture the duodenal mucosal wound. Accidental closure of the pancreatic or bile duct might result in pancreatitis or jaundice during the above process with clips.

Implantation of pancreatic duct stent has been generally the preferred route for the palliative drainage with fewer pancreatitis after EP[7,12,17,18]. Endoscopic bile drainage tube can also effectively prevent delayed complications for shunting bile and pancreatic juice to avoid erosion exposure of the duodenal ulcer[19-21]. As mentioned in our previous study, the mixture of bile and pancreatic juice could activate the trypsinogen to achieve a high digestive capacity. Active trypsin in the pancreatic duct would induce pancreatitis and erose the duodenal wound[22,23].

Kim et al[12] used wire-guide EP, requiring the insertion of a guide wire to the pancreatic duct before the papillectomy, to increase the success rate of pancreatic duct stenting.

However, a guide wire could also impede the expansion and angle of the snare, while making it difficult to resect larger adenomas[12]. Zolotarevsky et al[24] performed an RCT targeting pancreatic duct stents, and the spontaneous removal rates in 2 wk were obtained as 68.4% and 75.0% for 3-Fr (n = 40) and 5-Fr (n = 38) after EP, respectively. In this study, the novel autorelease bile duct supporter was successfully inserted in all patients through a guide wire using ERCP after EP, during which an experienced operator was required for the insertion of the guide wire. The gravity of the curved coil ensured the automatic shedding characteristics of this novel bile stent in 2 wk. No severe or fatal bleeding occur in the above 8 patients. The literature on ampullary papillectomy was examined, and it was found that the insertion of duct stent has been widely recommended by numerous endoscopists to reduce the risk of pancreatitis[25-27]. The autorelease bile duct supporter in 7 of 8 patients fell off naturally and arrived in colon nearly 10 d after the operation.

Acid-inhibitory drugs, enzyme inhibitors (somatostatin) and total parenteral nutrition were given through intravenous infusion till 7 d after EP. With the recovery of diet and bile secretion after 7 d, we presume that autorelease bile duct supporter start to liberate from bile duct and then arrived in colon nearly 10 d after EP. With the separation effect of bile stent shunting bile and pancreatic juice and secure closure by fibrin glue, no pancreatitis was detected in the postoperative period in this small-sample study with this autorelease bile duct.

Accordingly, novel autorelease bile duct supporter might be a safe method to prevent severe or fatal pancreatitis without removal by endoscopy. However, patients should be carefully monitored for pancreatitis after EP with giant tumor or greater manipulation around the orifice of the pancreatic duct for the effect arising from the pancreatic opening and pancreatic juice outflow.

The main limitations of this study were the small sample size (EP with a novel autorelease bile duct supporter conducted at a single center by an experienced endoscopist) and the relatively short follow-up time. Well-designed comparative studies are required to assess the findings of this study. For instance, one autorelease bile duct supporter did not come off successfully by itself, whereas it was removed by endoscopy, which could be attributed to the deep plastic wing opening and the improving friction. However, this has been the first study reporting the endoscopic pancreaticobiliary drainage with autorelease bile duct supporter to prevent delayed complications after EP.

In brief, it was confirmed that autorelease bile duct supporter could decrease the frequency of procedure-associated complications without second endoscopic retraction. Secure closure of the resection wound with clips and fibrin glue was indicated to be promising and important for the use of autorelease bile duct supporter. Well-designed larger-scale comparative studies are required to assess the finding of this study.

Conventional endoscopic papillectomy (EP) has been indicated to papilla adenoma of duodenum lesions. Temporarily placing a prophylactic stent in the pancreatic and bile duct can lower the risk of this perioperative complication.

A new bile duct stent may help with the complication after EP and streamline the procedure.

We evaluated the usefulness, convenient, safety, and short-term results of a novel autorelease bile duct supporter after EP procedure.

After EP, metallic endoclip and human fibrin sealant kit were applied for protection. The autorelease bile duct supporter fell into the duct segment and the intestinal segment. The bile was isolated from the pancreatic juice using an autorelease bile duct supporter, which protected the wound surface.

The autorelease bile duct supporter in 7 of 8 patients fell off naturally and arrived in colon 10 d after the operation. One of this autorelease bile duct supporter successfully removed using forceps or snare under endoscopy. No recurrence was identified during the 8-mo (ranging from 6-9 mo) follow-up.

Autorelease bile duct supporter could decrease the frequency of procedure-associated complications without second endoscopic retraction.

Well-designed larger-scale comparative studies are required to assess the finding of this study.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ardengh JC, Brazil; Ryozawa S, Japan S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Alderson D, Lavelle MI, Venables CW. Endoscopic sphincterotomy before pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary carcinoma. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1109-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fanning SB, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, Chung A, Kariyawasam VC. Giant laterally spreading tumors of the duodenum: endoscopic resection outcomes, limitations, and caveats. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:805-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bohnacker S, Soehendra N, Maguchi H, Chung JB, Howell DA. Endoscopic resection of benign tumors of the papilla of vater. Endoscopy. 2006;38:521-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Chathadi KV, Khashab MA, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Fonkalsrud L, Lightdale JR, Salztman JR, Shaukat A, Wang A, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in ampullary and duodenal adenomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:773-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cheng CL, Sherman S, Fogel EL, McHenry L, Watkins JL, Fukushima T, Howard TJ, Lazzell-Pannell L, Lehman GA. Endoscopic snare papillectomy for tumors of the duodenal papillae. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:757-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Burke CA, Beck GJ, Church JM, van Stolk RU. The natural history of untreated duodenal and ampullary adenomas in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis followed in an endoscopic surveillance program. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bohnacker S, Seitz U, Nguyen D, Thonke F, Seewald S, deWeerth A, Ponnudurai R, Omar S, Soehendra N. Endoscopic resection of benign tumors of the duodenal papilla without and with intraductal growth. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:551-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | De Palma GD, Luglio G, Maione F, Esposito D, Siciliano S, Gennarelli N, Cassese G, Persico M, Forestieri P. Endoscopic snare papillectomy: a single institutional experience of a standardized technique. A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;13:180-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamao T, Isomoto H, Kohno S, Mizuta Y, Yamakawa M, Nakao K, Irie J. Endoscopic snare papillectomy with biliary and pancreatic stent placement for tumors of the major duodenal papilla. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Singh P, Das A, Isenberg G, Wong RC, Sivak MV Jr, Agrawal D, Chak A. Does prophylactic pancreatic stent placement reduce the risk of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:544-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li S, Wang Z, Cai F, Linghu E, Sun G, Wang X, Meng J, Du H, Yang Y, Li W. New experience of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary neoplasms. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:612-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim SH, Moon JH, Choi HJ, Kim DC, Lee TH, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Park SH, Kim SJ. Usefulness of pancreatic duct wire-guided endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary adenoma for preventing post-procedure pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:838-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Farnell MB, Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG, Rowland CM, Tsiotos GG, Farley DR, Nagorney DM. Villous tumors of the duodenum: reappraisal of local vs. extended resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:13-21, discussion 22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mazaki T, Masuda H, Takayama T. Prophylactic pancreatic stent placement and post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2010;42:842-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kato M, Ochiai Y, Fukuhara S, Maehata T, Sasaki M, Kiguchi Y, Akimoto T, Fujimoto A, Nakayama A, Kanai T, Yahagi N. Clinical impact of closure of the mucosal defect after duodenal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Takimoto K, Imai Y, Matsuyama K. Endoscopic tissue shielding method with polyglycolic acid sheets and fibrin glue to prevent delayed perforation after duodenal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:46-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Inamdar S, Slattery E, Bhalla R, Sejpal DV, Trindade AJ. Comparison of Adverse Events for Endoscopic vs Percutaneous Biliary Drainage in the Treatment of Malignant Biliary Tract Obstruction in an Inpatient National Cohort. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:112-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moon JH, Choi HJ, Lee YN. Current status of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary tumors. Gut Liver. 2014;8:598-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ochiai Y, Kato M, Kiguchi Y, Akimoto T, Nakayama A, Sasaki M, Fujimoto A, Maehata T, Goto O, Yahagi N. Current Status and Challenges of Endoscopic Treatments for Duodenal Tumors. Digestion. 2019;99:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Catalano MF, Linder JD, Chak A, Sivak MV Jr, Raijman I, Geenen JE, Howell DA. Endoscopic management of adenoma of the major duodenal papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:225-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T, Kato Y, Yamashita Y. Impact of technical modification of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary neoplasm on the occurrence of complications. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jiang L, Ling-Hu EQ, Chai NL, Li W, Cai FC, Li MY, Guo X, Meng JY, Wang XD, Tang P, Zhu J, Du H, Wang HB. Novel endoscopic papillectomy for reducing postoperative adverse events (with videos). World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:6250-6259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | van Geenen EJ, van der Peet DL, Bhagirath P, Mulder CJ, Bruno MJ. Etiology and diagnosis of acute biliary pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:495-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zolotarevsky E, Fehmi SM, Anderson MA, Schoenfeld PS, Elmunzer BJ, Kwon RS, Piraka CR, Wamsteker EJ, Scheiman JM, Korsnes SJ, Normolle DP, Kim HM, Elta GH. Prophylactic 5-Fr pancreatic duct stents are superior to 3-Fr stents: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2011;43:325-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee TY, Cheon YK, Shim CS, Choi HJ, Moon JH, Choi JS, Oh HC. Endoscopic wire-guided papillectomy versus conventional papillectomy for ampullary tumors: A prospective comparative pilot study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:897-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Han J, Kim MH. Endoscopic papillectomy for adenomas of the major duodenal papilla (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:292-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Itoi T, Ryozawa S, Katanuma A, Kawashima H, Iwasaki E, Hashimoto S, Yamamoto K, Ueki T, Igarashi Y, Inui K, Fujita N, Fujimoto K. Clinical practice guidelines for endoscopic papillectomy. Dig Endosc. 2022;34:394-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |