Published online Jul 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7429

Peer-review started: September 24, 2021

First decision: December 2, 2021

Revised: December 11, 2021

Accepted: June 3, 2022

Article in press: June 3, 2022

Published online: July 26, 2022

Processing time: 289 Days and 18.4 Hours

Sporadic cases of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma in children, especially preschool children, have been reported in the literature.

We present a case of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma in a 4-year-old boy. The presenting symptoms, imaging findings, treatment, histological appearance, and follow-up data are described in detail. For this patient, we performed embolization on two occasions, and then, resected the tumor completely. During the treatment, the patient developed a soft-palate perforation due to aseptic necrosis. However, the healing ability was good, and the perforation healed spontaneously. We additionally reviewed all pediatric cases of extranasophary

Extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas can occur throughout childhood, and predominantly present with nasal obstruction and spontaneous rhinorrhagia.

Core Tip: Extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas can occur throughout childhood, but predominantly occur during adolescence. They present with similar symptoms. In our case, the clinical presentation was unusual due to the patient’s young age, the large tumor size, and the requirement of two embolization treatments. Soft palate perforation developed as a complication, but healed spontaneously during follow-up. Additionally, we performed a literature review to summarize the clinical characteristics of this rare tumor.

- Citation: Yan YY, Lai C, Wu L, Fu Y. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma in children: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(21): 7429-7437

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i21/7429.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7429

Angiofibromas are nasopharyngeal tumors that predominantly occur in adolescent boys. These tumors almost always originate in the region of the sphenopalatine foramen and enlarge to fill the postnasal space[1,2]. Angiofibromas that do not originate in this region are rare, and referred to as extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas[3]. Sporadic cases of extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas have been reported in the literature[2]. These types of angiofibromas most commonly originate from the maxillary sinus. Here, we describe a rare case of an extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma arising from the inferior turbinate and lateral wall of the nasopharynx in a child. The clinical presentation was unusual due to the patient’s young age, the large tumor size, and the requirement of two embolization treatments. Soft palate perforation developed as a complication, but healed spontaneously during follow-up. Additi

A 10-d history of epistaxis and nasal obstruction in the left nasal cavity.

A 4-year-old male reported to the ENT outpatient department of our institution with the chief complaints of epistaxis and nasal obstruction in the left nasal cavity for 10 d. The child had a sudden left nasal hemorrhage during sleep 10 days before, which was too large to stop by itself. He went to a local hospital for emergency treatment and stopped bleeding after filling the left nasal cavity with an inflated sponge. The next day, the child removed the expansive sponge by himself without obvious bleeding.Since then, the left nasal obstruction was persistent, accompanied by white purulent nasal discharge, which was difficult to blow out due to a large amount. Blood was sometimes seen in the nose, along with sleep snoring, accompanied by open mouth breathing and suffocation during sleep. Therefore, the patient was admitted to our hospital.

The child was previously healthy.

A pinkish lesion was seen in the total nasal passages of Bilateral nasal cavity

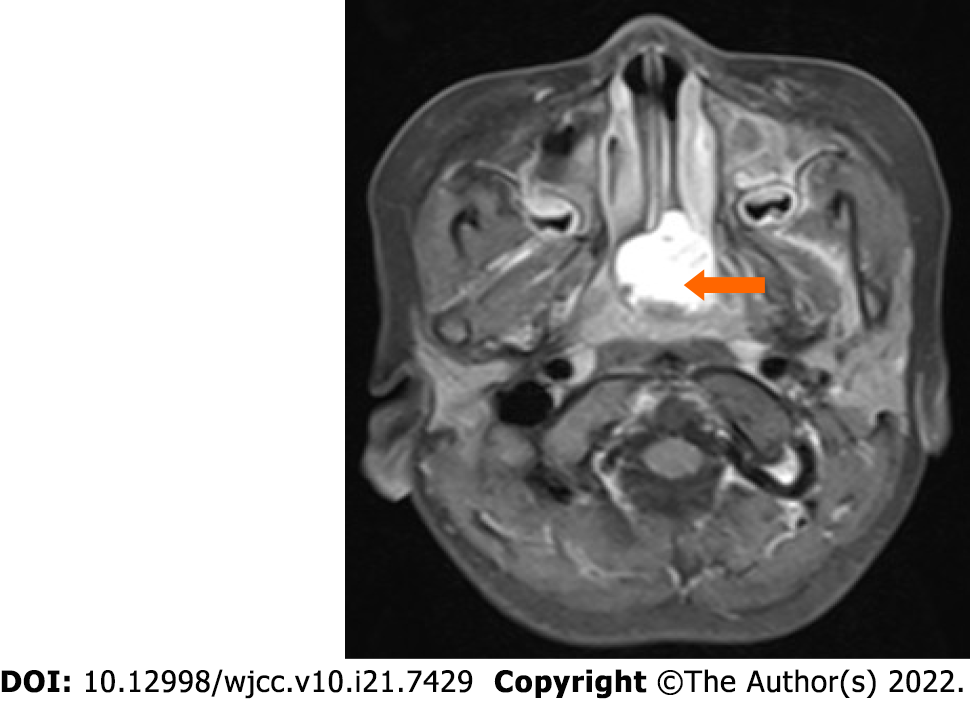

A Computed Tomography Scan of the paranasal sinuses was done which showed bilateral posterior nasal passage obstructiona, a 2.5 cm × 2.7 cm size Soft tissue density shadow in the nasopharyngeal,and there was no bony erosion.Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of paranasal sinus presented abnormal signal of nasopharynx with obvious enhancement, consideration of adolescent nasopharyngeal fibroangioma (Figure 1).

Nasopharyngealangiofibroma.

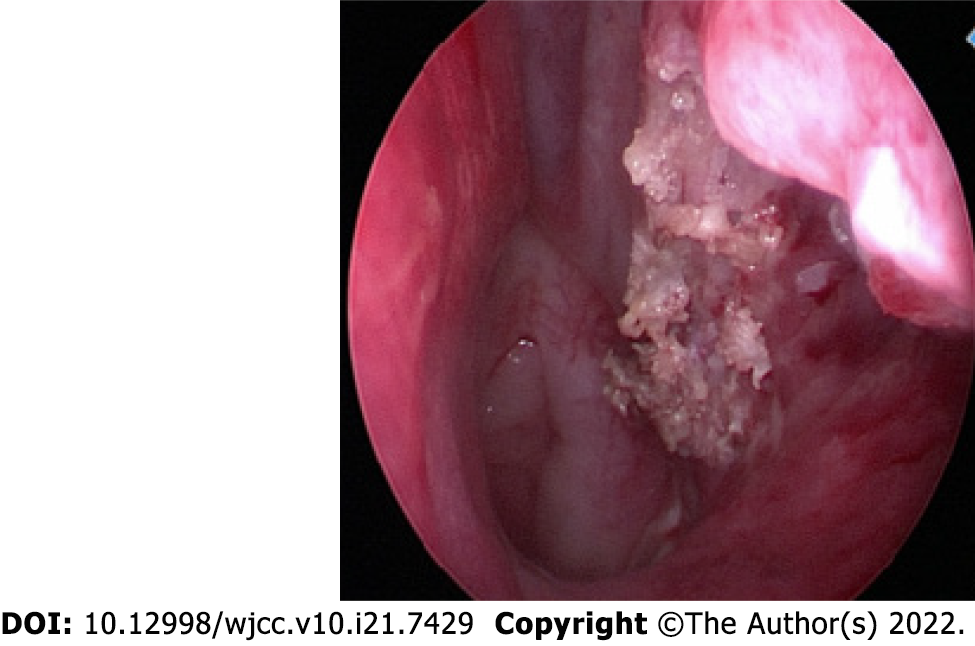

After two embolization treatments, we use a plasma knife to remove the tumor (Figure 2).

The tumor tissues were completely removed. A follow-up nasal endoscopy at 3 mo after the endoscopic excision showed smooth mucosa at the posterior end of the left inferior turbinate and on the lateral wall of the nasopharynx, with no obvious new lesions.

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is a benign tumor of the nasopharynx. These tumors mostly occur in adolescent boys, and appear to be more common in the Middle East and Indian subcontinent[4]. Although the etiology and pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma are not yet clear, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is believed to be caused by insufficient estrogen or relatively excessive androgen, which leads to hyperplasia of the vascular and fibrous tissues[5].

Due to the locally invasive nature of this tumor, it can widely involve the nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, the orbital, pterygopalatine, and inferior temporal fossae, and even invade the skull base and cavernous sinus. Angiofibroma of extranasopharyngeal origin is rare. Extranasopharyngeal tumors most commonly originate in the maxillary sinus, but have also been reported to originate in the ethmoid sinus, sphenoid sinus, frontal sinus[7], middle turbinate[8], inferior turbinate[9], septum[10], cheek[11], and conjunctiva[6]. We searched the PubMed, Baidu Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science databases for the search term “extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma.” A review of the retrieved literature revealed that a total of 45 cases, including ours, of this tumor have been reported in children[1,2,12,13]. We have also formulated a table that was first compiled by Ali and Jones in 1982 and updated it with recent cases of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma in children (age < 18 years), including the present case (Table 1)[1]. The main features of these cases have been summarized in Table 2.

| No | Ref. | Site of origin | Age | Sex |

| 1 | Munson[21], 1941 | Maxillary sinus | 15 years | M |

| 2 | Radcliffe[22], 1951 | Ethmoid sinus | 16 years | M |

| 3 | Alajmo and Fini-Storchi[26], 1962 | Maxillary sinus | 9 years | M |

| 4 | Whitlock et al[23], 1961 | Cheek | 16 years | M |

| 5 | Alajmo and Fini-Storchi[26], 1962 | Maxillary sinus | 6 years | M |

| 6 | Hora and Brown[26], 1962 | Maxillary sinus | 13 years | M |

| 7 | Furstenborg and Boles[26], 1963 | Ethmoid sinus | 1 months | M |

| 8 | Minicone[26], 1964 | Conjunctiva | 17 years | M |

| 9 | Ogura[26], 1965 | Maxillary sinus | 16 years | M |

| 10 | Chaikovskii[26], 1967 | External nose | 14 years | F |

| 11 | Szczepanski et al[24], 1967 | Ethmoid sinus | 13 years | F |

| 12 | Manigla[26], 1969 | Maxillary sinus | 15 years | M |

| 13 | Pathak[26], 1970 | Maxillary sinus | 18 years | M |

| 14 | Beeden and Alexander[26], 1971 | Oropharynx and hypopharynx | 1 years | M |

| 15 | Charkabti[26], 1973 | Maxillary sinus | 17 years | M |

| 16 | Rye[26],1973 | Maxillary sinus | 17 years | M |

| 17 | Stewart and O’Brien[26], 1973 | Molar and retromolar | 10 years | M |

| 18 | Ramajaneyulu[26], 1974 | Maxillary sinus | 17 years | M |

| 19 | Yamagiwa[26], 1974 | Sphenoid sinus | 14 years | M |

| 20 | Isherwood et al[25], 1975 | Pterygomaxillary fissure, infratemporal region | 13 years | M |

| 21 | Krutchkoff[30], 1977 | Maxillary sinus | 12 years | M |

| 22 | Reddy[26], 1979 | Molar and retromolar area | 14 years | F |

| 23 | Obiako et al[31], 1983 | Roof of nasal cavity | 12 years | M |

| 24 | Hiraide and Matsubara[27], 1984 | Nasal septum | 13 years | M |

| 25 | Sarpa and Novelly[28], 1989 | Nasal septum | 9 years | M |

| 26 | Kitano et al[32], 1992 | Maxillary sinus | 13 years | M |

| 27 | Manjalay et al[33], 1992 | Maxillary sinus | Newborn | M |

| 28 | Gaffney et al[18], 1997 | Inferior turbinate | 9 years | M |

| 29 | Schick et al[6], 1997 | Lacrimal sac | 15 months | M |

| 30 | Schick et al[6], 1997 | Paranasal sinus | 9 years | M |

| 31 | Schick et al[6], 1997 | Sphenoid sinus | 6 years | M |

| 32 | Huang et al[8], 2000 | Middle turbinate | 14 years | M |

| 33 | Handa et al[12], 2001 | Nasal septum | 8 years | M |

| 34 | Panesar et al[2], 2003 | Maxillary sinus | 1 years | M |

| 35 | Gupta et al[34], 2006 | Infratemporal region | 13 years | M |

| 36 | Castillo et al[29], 2006 | Nasal septum | 9 years | M |

| 37 | Ifeacho and Caulfield[35], 2011 | Middle turbinate | 14 years | M |

| 38 | Singhal et al[17], 2014 | Nasal septum | 12 years | M |

| 39 | Ganguly et al[16], 2017 | Nasal septum | 7 years | M |

| 40 | Singh et al[17], 2018 | Nasal septum | 9 years | F |

| 41 | Kim et al[20], 2019 | Inferior turbinate | 9 years | M |

| 42 | Kim et al[20], 2019 | Inferior turbinate | 16 years | M |

| 43 | Kim et al[20], 2019 | Inferior turbinate | 8 years | F |

| 44 | Kim et al[20], 2019 | Inferior turbinate | 12 years | F |

| 45 | Our case | Inferior turbinate and lateral wall of nasopharynx | 4 years | M |

| Variable | N (%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 39 (86.7%) |

| Female | 6 (13.3%) |

| Age at the time of surgery | |

| ≤ 6 years | 8 (17.8%) |

| 7-12 years | 15 (33.3%) |

| 13-18 years | 22 (48.9%) |

| Site | |

| Maxillary sinus | 15 (33.3%) |

| Ethmoid sinus | 3 (6.7%) |

| Sphenoid sinus | 2 (4.4%) |

| Nasal septum | 7 (15.6%) |

| Inferior turbinate | 6 (13.3%) |

| Middle turbinate | 2 (4.4%) |

| Roof of nasal cavity | 1 (2.2%) |

| Lacrimal sac | 1 (2.2%) |

| Cheek | 1 (2.2%) |

| Conjunctiva | 1 (2.2%) |

| External nose | 1 (2.2%) |

| Molar and retromolar area | 2 (4.4%) |

| Oropharynx and hypopharynx | 1 (2.2%) |

| Infratemporal region | 2 (4.4%) |

Of the 45 patients with extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma, 39 (86.7%) were boys, and 6 (13.3%) were girls, yielding a male-to-female ratio of 13:2. The highest proportion of cases occurred in adolescence (48.9%), which is consistent with the reported prevalence of the disease in adolescents[2]. The second most affected age group was children aged 7-12 years, who accounted for 35.6% of cases. Infants accounted for the smallest proportion of cases (15.5%). Thus, we found that extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas can occur throughout childhood, with non-adolescent children accounting for half of the total number of cases. The top three sites of occurrence of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma in children were the maxillary sinus, nasal septum, and inferior turbinate, which accounted for 31.1%, 20%, and 13.3% of cases, respectively. Other sites were less frequently involved, and included the ethmoid sinus (6.7%), sphenoid sinus (4.4%), and middle turbinate (4.4%).

The main clinical manifestations of extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma were nasal obstruction (80%) and spontaneous rhinorrhagia (60%). Other manifestations included secondary headache; sinusitis symptoms; tumor invasion of the pharyngeal opening of the eustachian tube, leading to conductive hearing loss; and tumor enlargement causing cheek swelling[14]. In our patient, the main symptoms were nasal obstruction and nosebleed, which is consistent with the reported findings.

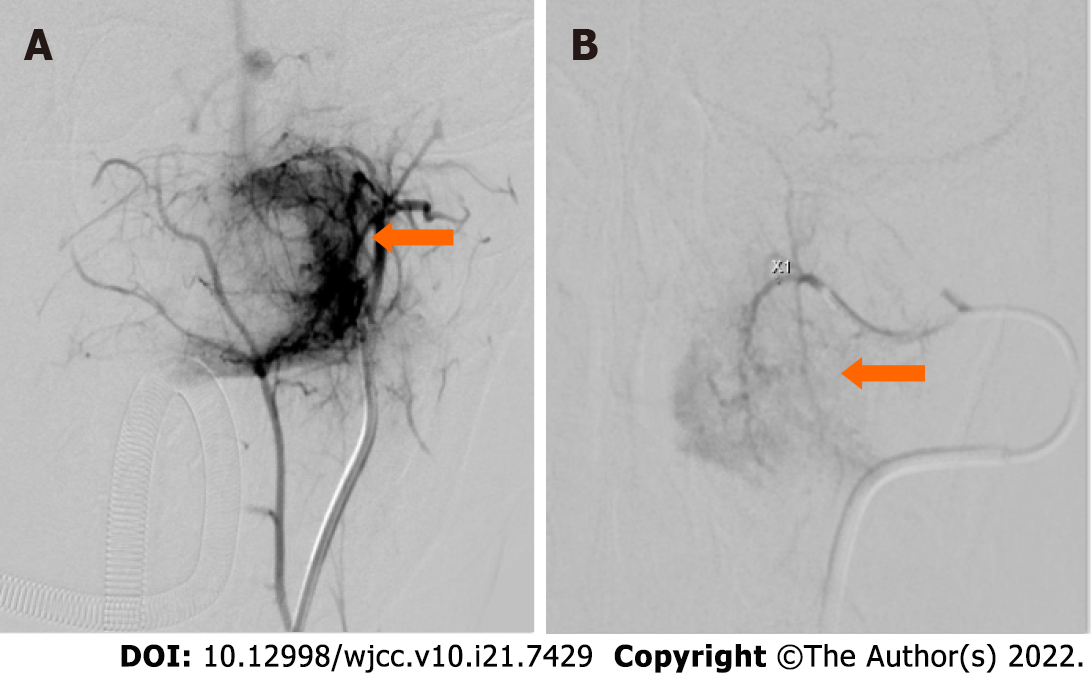

Preoperative examinations for extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma include nasal endoscopy, CT, MRI, and angiography, which are required to fully evaluate the tumor extent, blood supply, and main blood vessels. Prior to the clinical diagnosis, intraoperative hemorrhage can be avoided by performing preoperative angiography and feeding-vessel embolization[15]. However, none of the children in the previous cases underwent preoperative embolization. This shows that extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma is less vascular, and thus, the chances of massive hemorrhage are low. For our patient, we chose to perform a second embolization 28 d after the first embolization, and then, remove the tumor. This is because the tumor had an abundant blood supply, was large, and its boundaries could not be clearly determined. Moreover, angiography showed early arteriovenous enhancement and abundant arteriovenous malformation, so we could not rule out the possibility of arteriovenous fistula (Figure 3A). Therefore, considering the high risk of intraoperative bleeding and the difficulty in achieving complete tumor resection, we planned to perform a second embolization after tumor necrosis and shrinkage had set in (Figure 3B).

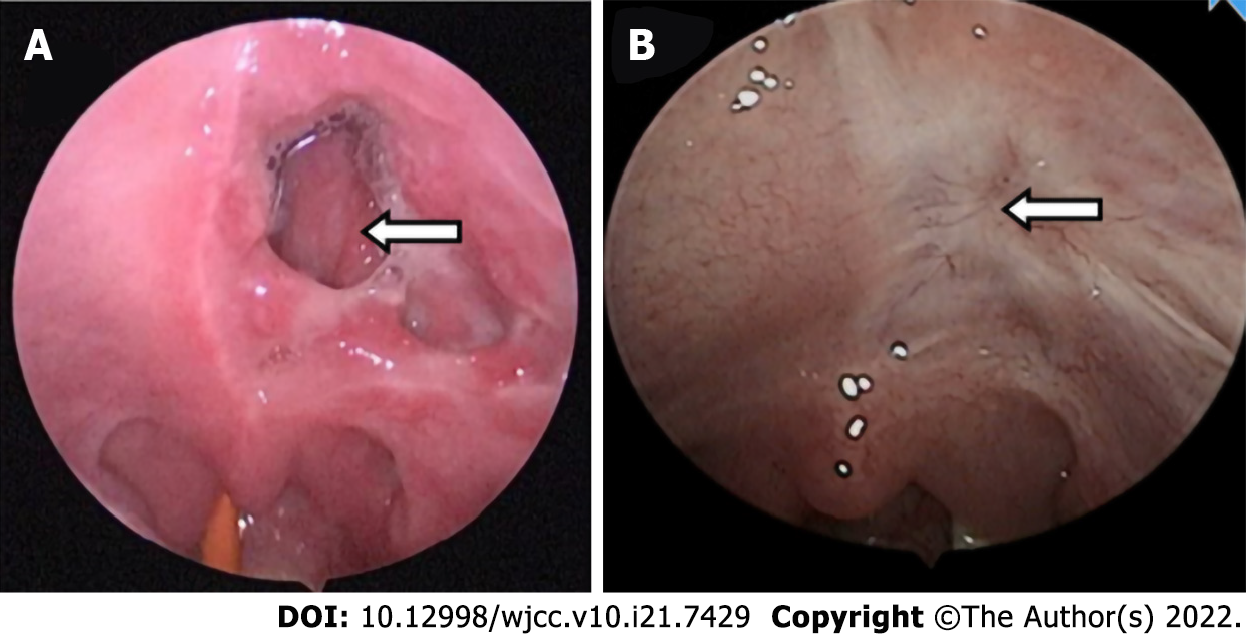

After the first embolization, the patient developed soft palate necrosis as a complication, which has not been previously reported (Figure 4A). The patient experienced reflux of food through the perforation in the soft palate and into the nasal cavity. As the perforation gradually narrowed, this symptom lessened and then disappeared. It is possible that the arteries supplying the soft palate were simultaneously embolized during the first embolization of the pterygoid segment of the internal maxillary artery, resulting in ischemic necrosis of the soft palate. However, because the perforation was caused by aseptic necrosis, it healed well, and had completely closed by the time of the reexamination 3 mo after the operation (Figure 4B).

The main treatment for extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma is surgical resection, which is usually performed via the transnasal endoscopic, lateral rhinotomy incision, or transoral approaches, depending on the site and size of the tumor. We reviewed the surgical procedures performed for extrapharyngeal angiofibromas in children over the last 30 years, and found that tumors in the septum, inferior turbinate, and middle turbinate were mostly commonly removed using nasal endoscopic resection (e.g., Ganguly et al[16] and Singh et al[17]). Gaffney et al[18] and Huang et al[8] performed lateral rhinotomy to remove tumors originating from the inferior and middle turbinates, respectively. Handa et al[12] used an external approach incision in the left alar crease to resect a nasal septum tumor, which was found to be firmly adhered to the nasal septum at the junction of the quadrangular cartilage and the bony septum. Endoscopic and KTP laser-assisted surgery has also been used[19]. Panesar et al[2] used the endoscopic approach for the first time to resect a tumor located in the maxillary sinus; however, their patient developed tumor recurrence after the operation, and another midfacial degloving procedure was used for the complete removal of the recurrent tumor. In the present study, we used a nasal endoscopic approach. During the surgery, the tumor was completely excised along with the tissues in a 0.5-cm margin around the tumor to minimize intraoperative hemorrhage. We used a plasma knife to remove the tumor, which helped to clear the operative field and reduced the probability of intraoperative bleeding and complications. There was little intraoperative bleeding in our patient, and nasal packing was not performed after tumor removal, which helped to minimize postoperative pain.

Extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas can occur throughout childhood, but predominantly occur during adolescence. They present with similar symptoms such as nasal obstruction and spontaneous rhinorrhagia. When post-embolization complications occur, like in our case, they can be a challenge to manage and treat. However, aseptic necrosis due to embolism is associated with good healing ability and spontaneous repair.

The authors express their appreciation for Dr. Liu Yang’s assistance with the pathology micrographs.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Noh CK, South Korea; Saad K, Egypt A-Editor: Valencia GA S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Pathak PN. Extranasopharyngeal juvenile angiofibroma--a case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1970;84:449-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Panesar J, Vadgama B, Rogers G, Ramsay AD, Hartley BJ. Juvenile angiofibroma of the maxillary sinus. Rhinology. 2004;42:171-174. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sarpa JR, Novelly NJ. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;101:693-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gullane PJ, Davidson J, O'Dwyer T, Forte V. Juvenile angiofibroma: a review of the literature and a case series report. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:928-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dwight AL, Ramanath Rao, John Smeyer. Hormonal receptor determination in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibmmas. Cancer. 1980;46:547-551. |

| 6. | Schick V, Kind M, Draf W, Weber R, Lackmann GM. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma in a 15-month-old child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;42:135-140. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim JS, Kwon SH, Kim JS, Jung JY, Heo SJ. Extranasopharyngeal Angiofibroma of the Frontal Sinus. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30:e432-e433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huang RY, Damrose EJ, Blackwell KE, Cohen AN, Calcaterra TC. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;56:59-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Singh GB, Agarwal S, Arora R, Doloi P, Kumar D. A Rare Case of Angiofibroma Arising from Inferior Turbinate in a Female. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:MD07-MD08. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hamdan AL, Moukarbel RV, Kattan M, Natout M. Angiofibroma of the nasal septum. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2012;21:653-655. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Dere H, Ozcan KM, Ergul G, Bahar S, Ozcan I, Kulacoglu S. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the cheek. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Handa KK, Kumar A, Singh MK, Chhabra AH. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma arising from the nasal septum. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2001;58:163-166. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim HD, Choi IS. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma mimicking choanal polyp in patients with chronic paranasal sinusitis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019;46:302-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | López F, Triantafyllou A, Snyderman CH, Hunt JL, Suárez C, Lund VJ, Strojan P, Saba NF, Nixon IJ, Devaney KO, Alobid I, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Hanna EY, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Nasal juvenile angiofibroma: Current perspectives with emphasis on management. Head Neck. 2017;39:1033-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Katsiotis P, Tzortzis G, Karaminis C. Transcatheter arterial embolisation in nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Acta Radiol. 1979;20:433-438. |

| 16. | Ganguly S, Gawarle SH, Keche PN. Extra-Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma in a Pre-Pubertal Child. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2017;11:XD01-XD02. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Singh GB, Shukla S, Kumari P, Shukla I. A rare case of extra-nasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the septum in a female child. J Laryngol Otol. 2018;132:184-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gaffney R, Hui Yau, Vojvodich S, Forte V. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibromas of the inferior turbinate. Intl J Ped Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;40:177-180. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hazarika P, Nayak DR, Balakrishnan R, Raj G, Pillai S. Endoscopic and KTP laser-assisted surgery for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23:282-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim HD, Choi IS. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma mimicking choanal polyp in patients with chronic paranasal sinusitis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019;46:302-305. |

| 21. | Munson FT. Angiofibroma of the maxilly sinus.Annals of otology. Rhinology and Laryngology. 1941;50:561-569. |

| 22. | Radcliffe A. Ethmoidal Fibroangioma. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 1951;65:786-787. |

| 23. | Whitlock RIH. Angiofibroma of Cheek. British Dental Journal. 1961;111:372-374. |

| 24. | Szczepanski J, Perlowski H. Vascular tumours of the ethmoid sinus. Polski Tygdnik Lekarski. 1967;22:1503-1504. |

| 25. | Isherwood I, Dogra TS, Farrington WT. Extranasopharyngeal juvenile angiofibroma. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 1975;89:535-544. |

| 26. | Ali S, Jones WI. Extranasopharyngeal Angiofibromas. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 1982;96:559-565. |

| 27. | Hiraide F, Matsubara H. Juvenile nasal angiofibroma: a case report. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1984;239:235-41. |

| 28. | Sarpa JR, Novelly NJ. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;101:693-697. |

| 29. | Castillo MP, Timmons CF, McClay JE. Autoamputation of an extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the nasal septum. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2006;1:267-70. |

| 30. | Krutchkoff DJ, Matteson SR, Mark H, Hasson J. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: an unusual p source arch otolaryngol. Arch Otolaryngol. 1977;103:553-556. |

| 31. | Obiako MN, Jacobs A. An isolated case of juvenile angiofibroma in the nasal cavity. Ear nose & throat journal. 1983;62:70. |

| 32. | Kitano M, Landini G, Mimura T. Juvenile angiofibroma of the maxillary sinus-A case report. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 1992;21:230-232. |

| 33. | Manjalay G, Hoare TJ, Pearman K, Green NJ. A case of congenital angiofibroma. Intl J Ped Otorhinolaryngol. 1992;24:275-278. |

| 34. | Gupta M, Motwani G, Gupta P. Extranasopharyngeal angiofibroma arising from the infratemporal region. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;58:312-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ifeacho SN, Caulfield HM. A rare cause of paediatric epistaxis: lobular capillary haemangioma of the nasal cavity. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |