Published online Jul 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.7116

Peer-review started: December 31, 2021

First decision: February 14, 2022

Revised: February 28, 2022

Accepted: May 28, 2022

Article in press: May 28, 2022

Published online: July 16, 2022

Processing time: 185 Days and 9.8 Hours

Germ cell tumors (GCTs) account for 2% of human malignancies but are the most common malignant tumors among males aged 15-35. Since 1983, an association between mediastinal GCT (MGCT) and hematologic malignancies has been recognized.

We report a case in which malignant histiocytosis was associated with mediastinal GCTs. The clinical data of a male patient with MGCT admitted to Beijing Children's Hospital were collected retrospectively. The patient was first diagnosed according to imaging and pathological features as having MGCT, and was treated with surgery and chemotherapy. One year after stopping che

Physicians should recognize the possibility of hematologic malignancies being associated with MGCT. Suitable sites should be selected for pathological examination.

Core Tip: Association between mediastinal germ cell tumor (MGCT) and hematologic malignancies has been recognized. We report a case in which the malignant histiocytosis were associated with MGCT. The patient was diagnosed as MGCT first, and one year after stopping chemotherapy, imaging showed metastases in mediastinum, retroperitoneal lymph node and adjacent tissues. Then he was diagnosed as malignant histiocytosis according to pathological examination, and accepted chemotherapy. The patient has been followed up for 10 mo with no sign of progression or relapse. Physicians who take care of patients with MGCT should be aware of the possibilities of associated hematologic malignancies.

- Citation: Yang PY, Ma XL, Zhao W, Fu LB, Zhang R, Zeng Q, Qin H, Yu T, Su Y. Malignant histiocytosis associated with mediastinal germ cell tumor: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(20): 7116-7123

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i20/7116.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.7116

Germ cell tumors (GCTs) account for 2% of human malignancies but are the most common malignant tumors in males aged 15-35. Mediastinum and retroperitoneum are the two major sites of extragonadal GCTs[1]. Since Nichols et al[2] reported an association between hematologic malignancies and mediastinal GCTs in 1985, an association between mediastinal GCTs (MGCTs) and hematologic malignancies has been recognized[3]. One in every 17 patients with primary mediastinal nonseminomatous GCTs develop an incurable hematologic malignancy[4].

We report here a case in which malignant histiocytosis was associated with MGCTs.

A 13-year-old male was admitted to our hospital in April 2019, with the symptoms of chest pain, cough and fever.

The patient’s symptoms had started 20 d prior with chest pain, cough and fever, for which he had undergone no treatment.

The patient had no relevant medical history.

In particular, there were no abnormalities in his birth history, maternal pregnancy history or family history.

The patient’s temperature was 38.1 °C, heart rate was 110 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 106/60 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room air was 95%. The clinical examination revealed low breath sounds in the right lung, without any other pathological signs.

Alpha fetoprotein (AFP) was elevated (2149.83 ng/mL; normal range: 0-9 ng/mL). The blood routine, blood biochemistries, urine analysis and tests of other tumor makers yielded findings within the normal ranges.

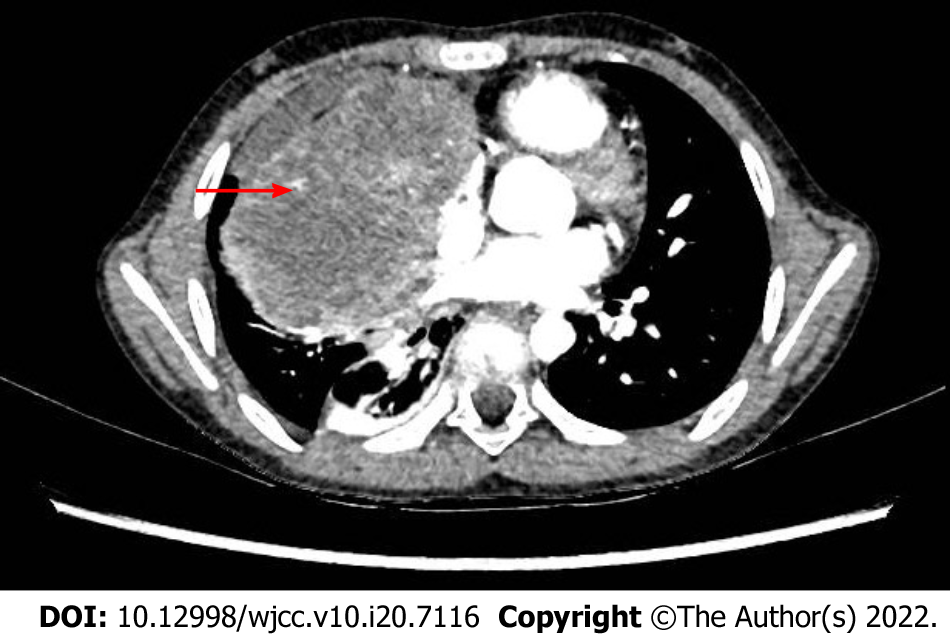

Enhanced computerized tomography (CT) of the chest indicated soft tissue occupation of the right anterior mediastinum, with a largest diameter of 10 cm (Figure 1). Imaging examination of other parts of the body showed no metastatic lesions, and no tumor cell was found in bone marrow smears. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT was not performed at that time.

The patient accepted thoracoscopic mediastinal mass biopsy, and the pathologic diagnosis of two hospitals were both yolk sac tumor.

The patient was diagnosed with MGCT, of which the Children's Oncology Group staging was III.

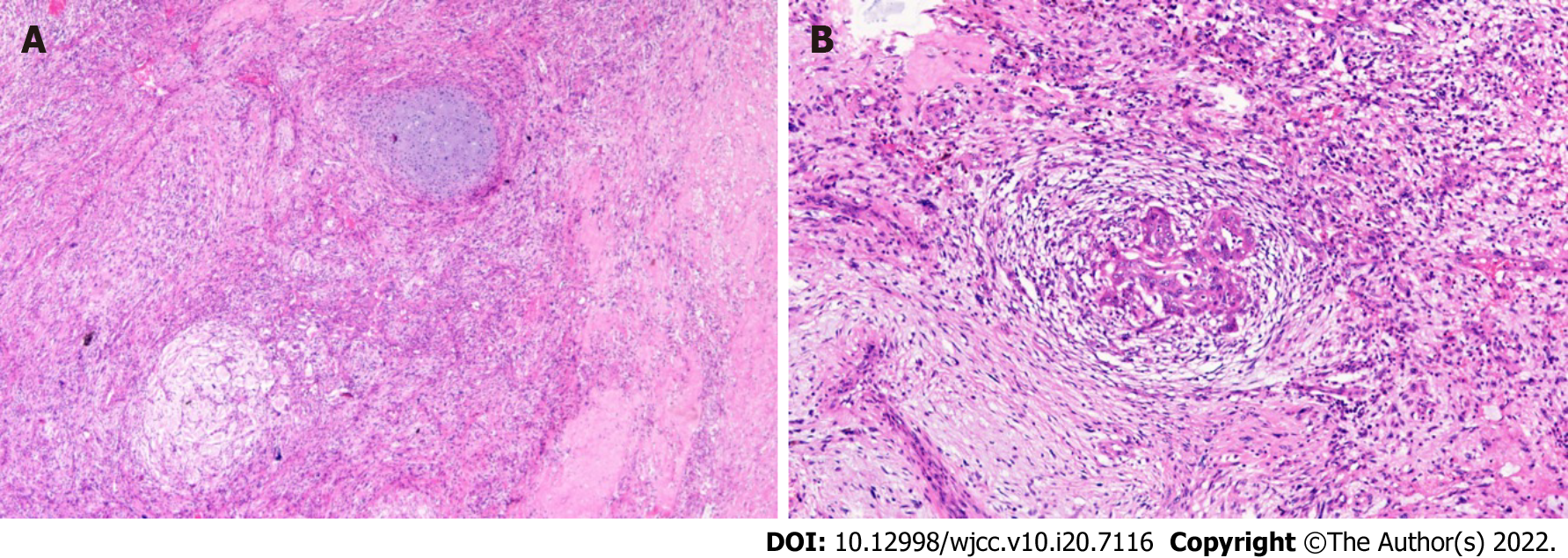

The patient received chemotherapy, consisting of one course of the PEB regimen and three courses of the C-PEB regimen. After the 4th course, he accepted surgery in July 2019, during which the tumor was completely resected and pathological examination showed mixed GCT (yolk sac tumor and immature teratoma) (Figure 2). The patient then continued to receive chemotherapy, consisting of two courses of the PEB regimen. Chemotherapy was stopped in August 2019.

Regular assessment by imaging examination and testing for tumor markers revealed that the patient remained stable until 1 year after stopping the chemotherapy. In August 2020, routine ultrasound showed new lesions.

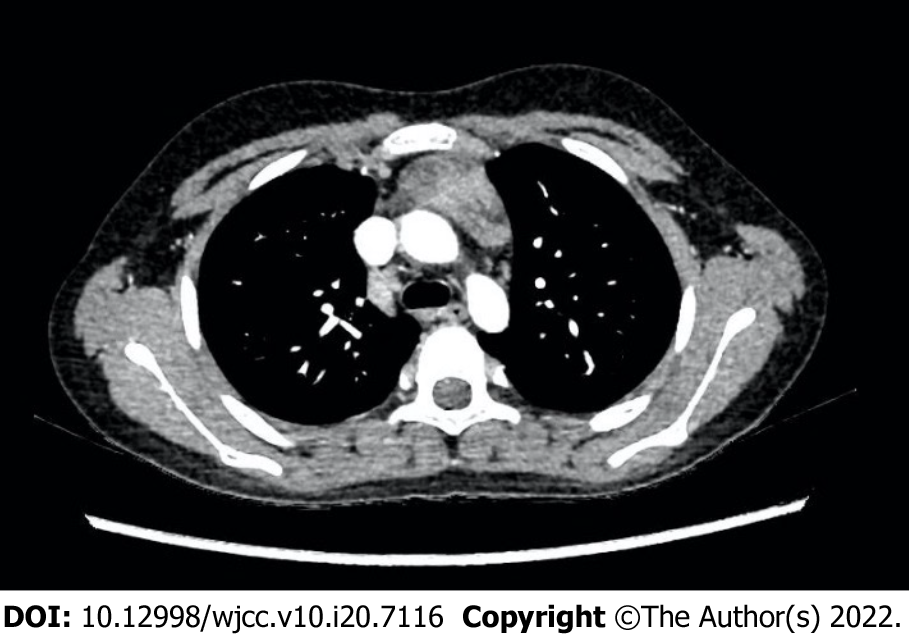

Ultrasound showed hypoechoic lesions with obscure boundaries in the anterior mediastinum and liver, measuring 2 cm × 2 cm and 0.3 cm × 0.4 cm respectively. Multiple poorly structured lymph nodes were seen in the hepatic hilar region. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen also indicated metastasis of liver, hilar hepatis, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Chest CT showed thickening of the anterior mediastinum (Figure 3). PET/CT showed metastases in the right supraclavicular, mediastinum, hilar region and retroperitoneal lymph node, right pleura, right lung, and right para-cardiac margin.

AFP was re-examined several times and the results were normal. Bone marrow puncture and biopsy showed no abnormalities. Blood routine showed that platelet count had decreased temporarily, to a range of 80 × 109/L to 110 × 109/L (normal range: 100 × 109/L to 400 × 109/L). Blood biochemistry showed elevated alanine aminotransferase, ranging between 400 IU/L and 500 IU/L (normal range: 5 IU/L to 40 IU/L).

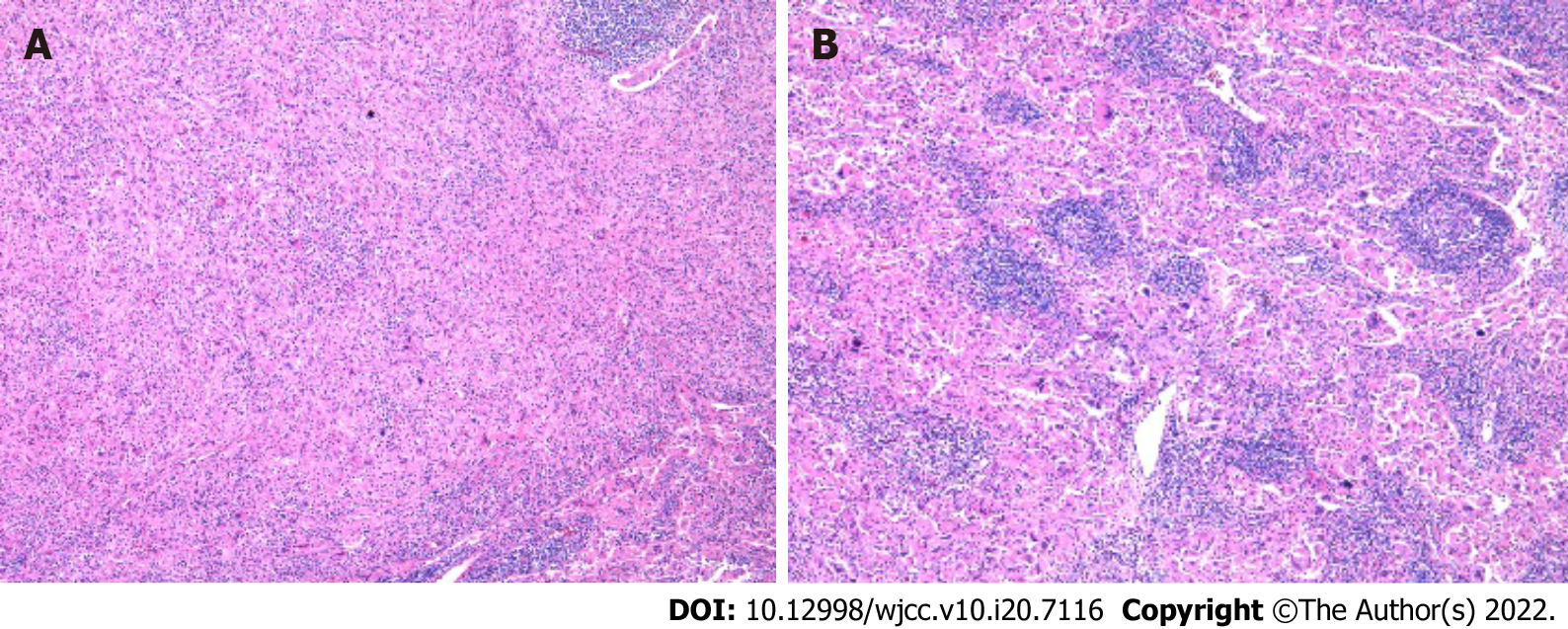

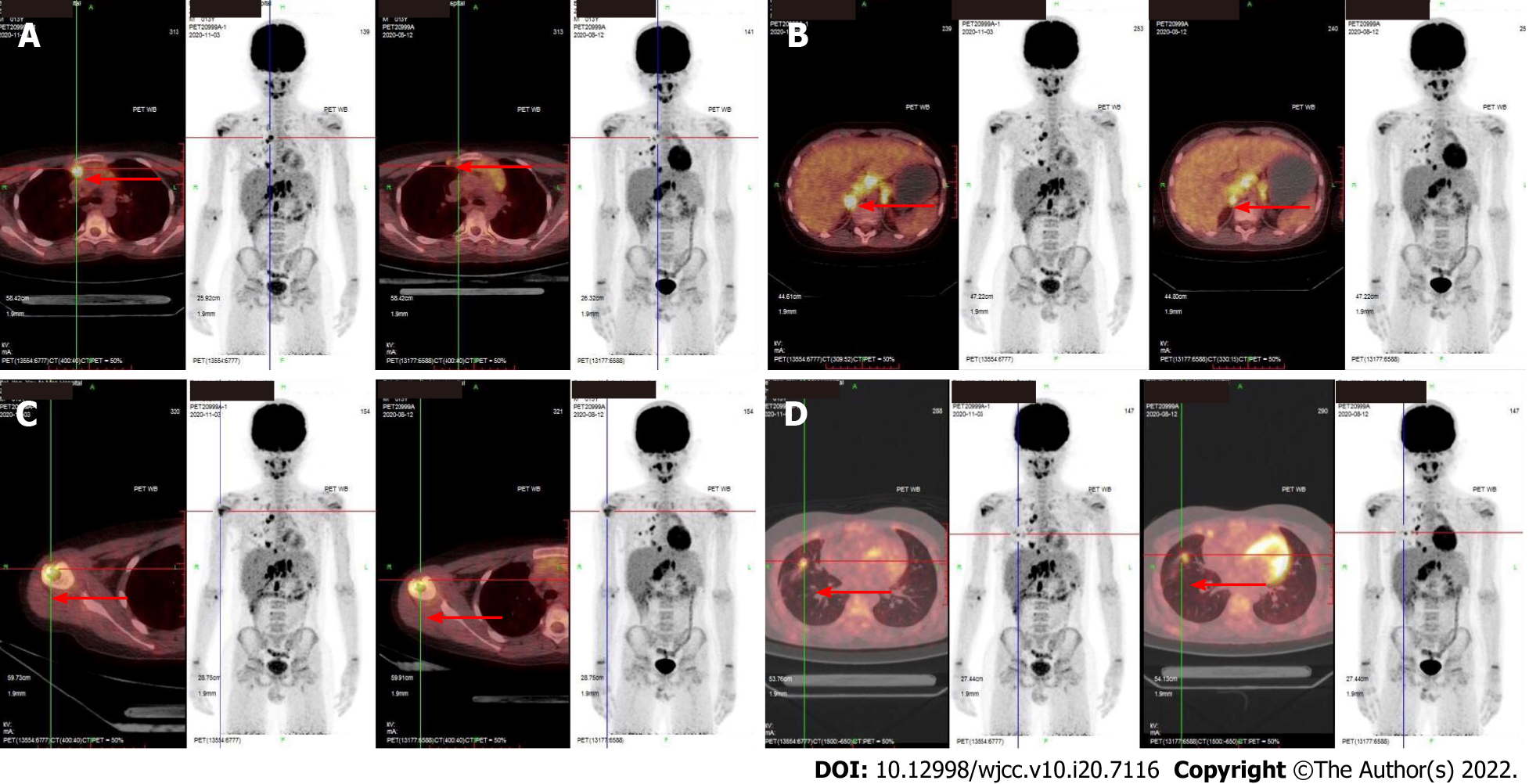

Due to the difficulty of judging whether the lesions suggested relapse of primary tumor or a new disease, the patient accepted resection of the mediastinum mass in August 2020. Pathological examination of two hospitals leaned towards the conclusion of inflammatory pseudotumor, which is a borderline or low-grade tumor with no need for chemotherapy. Another two hospitals were inclined to conclude the mass to be due to proliferation of fibroblasts. The clinicians could not explain the fact that the tumor had most likely metastasized distantly. Therefore, in October 2020, peritoneal and hilar lymph nodes’ resection and liver nodular biopsy were performed. Pathological examination led to the liver sample and hilar lymph nodes being identified as non-Langerhans histocytoproliferative lesions, which were consistent with systemic juvenile xanthogranuloma by histological morphology and immunophenotypic characteristics (Figure 4). The immunohistochemical results showed CD20 (lymphocyte+), CD3 (lymphocyte+), CD68 (histocyte+), S-100 (-), hepatocyte (residual hepatocyte+), and Ki-67 (8%). Hilar lymph nodes had characteristics of Rosai-Dorfman lesions with malignant transformation (i.e., had morphological characteristics and immunophenotype of histiocytic sarcoma), and the immunohistochemical results showed CD30 (activate cells+), CK (AE1/AE3) (-), CD1a (-), Langerin (-), P53 (little+), BRAF (-), ALK (-), Desmin (-), SMA (scattered+), EMA (-), CD21 (FDC net+), Ki-67 (15%, high expression in heterotypic macrocells), CD56 (-), CD4 (+), CD123 (-), CD117 (-), CD33 (+), CD35 (-), CD99 (-), CD68 (+), and S-100 (scattered+). The second PET/CT in November 2020, 3 mo after the first exam, showed progression of the tumor, as bilateral supraclavicular, mediastinum, hilar region, retroperitoneal lymph node metastases were increased in number; the metastases in the right lung and the right side of the heart margin were approximately the same as before but more metastases were observed in the right pleura. Metastases were found in the head of the right humerus, the upper segment of the right radius, and the right adnexa of the 4th lumbar vertebra (Figure 5).

According to the imaging features and pathological conclusions, the patient was diagnosed with malignant histiocytosis associated with MGCT.

The patient accepted chemotherapy regularly, undergoing a total of 14 courses with vindesine, cytarabine and dexamethasone administered as 3 mg/m2 of vindesine on day 1, 150 mg/m2/d of cytarabine on days 1-5 and 6 mg/m2/d of dexamethasone on days 1-5, with one course given every 3-4 wk. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was suggested, but his family refused for economic reasons.

The patient has been followed up for 10 mo since the diagnosis of malignant histiocytosis, and both imaging examination and testing of tumor markers have shown no signs of progression or relapse for either GCT or malignant histiocytosis.

The association between GCTs and hematologic malignancies has been described by many clinical centers. Most of these cases were seen in young males[5] and have been described only for patients with nonseminomatous MGCTs, especially for those patients having evidence of yolk sac tumor differentiation[3]. Yolk sac or embryonal cell carcinoma in combination with teratoma was particularly common[6]. The risk of developing hematologic disorders was statistically significantly increased in patients with primary nonseminomatous MGCTs in comparison with the age-matched general population[7]. The hematologic diseases associated with MGCTs include myeloid neoplasm, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, histiocytosis[8], myelodysplastic syndrome, and mast cell leukemia[8]. For those cases associated with histiocytosis, most were not identified as specific pathologies. The remaining few cases were respectively confirmed as histiocytic sarcoma and Langerhans cell histiocytosis[9]. The median time from the diagnosis of the primary MGCT to the diagnosis of the hematologic neoplasia reported in the literature ranges from 4 mo to 6 mo, and most cases were within 1 year[4,6,7,8]. Ten percent to thirty percent of patients observed presented with a simultaneous onset of both disorders in two investigations[7]. The case presented in this report was that of a 13-year-old boy, in the age group with a high incidence of GCT, with a tumor originating in the mediastinum, the component of which includes yolk sac tumor. New lesions were found after treatment, which were confirmed to be several types of histiocytosis, including Juvenile yellow granuloma, Rosai-Dorfman disease, and histiocytic sarcoma. It is worth noting that we found multiple components in the liver and mediastinum lesions of the patient, and the malignancy degrees of them are different. In a previous case report, a mediastinal tumor was finally diagnosed as a mature teratoma with two malignant components 3/4 angiosarcoma and granulocytic sarcoma[10].

Cytogenetic and molecular mechanisms of the relevance between GCTs and hematologic malignancies has been investigated in the past decades. Research findings imply that hematologic malignancy and MGCTs arise from a common progenitor cell. MGCTs, unlike gonadal and retroperitoneal GCTs, contain areas of yolk sac tumor that have a mesenchyme-like pluripotent component. These areas may be the location at which GCTs are transformed into malignancies typical of nongerminal tissues. In addition, teratocarcinoma cells have been shown to differentiate along hematopoietic lineages in vitro and to form hematopoietic tissue in mosaic mice[7]. As for the molecular mechanisms, isochromosome 12p is a cytogenetic marker in MGCT[8] and was commonly seen in MGCTs with hematologic malignancies, whereas it was never observed in de novo acute myelocytic leukemia (AML). In addition, mutations in TP53 were present in 91% of patients with MGCTs with hematologic malignancies vs 61% of patients with MGCTs lacking hematologic malignancies and in only 9% of patients with de novo AML. Activating mutations in KRAS and NRAS accounted for 63%, 37% and 13% in the three conditions above, respectively. Moreover, the reason why the association between these two diseases was obviously more common in male adolescents has not been revealed clearly.

Hematologic malignancies associated with MGCTs have to be distinguished from therapy-related secondary leukemias. Leukemias caused by alkylating agents or topoisomerase II inhibitor, are typically diagnosed 5-7 years and 2-3 years following therapy, respectively. Taking into account that the time between the onset of two diseases in our case was only 1 year, malignant histiocytosis was considered to be associated with GCT, instead of a second tumor related to treatment.

Although the relevance of these two diseases has been recognized for nearly 30 years, it has been marked by a very poor outcome, despite modern therapy for both of the cancer types[4]. These patients usually demonstrate a clinically fulminant course[5]; patients either die before treatment, do not respond to antileukemic therapy, or achieve only short remissions[7]. In the case we presented above, PET/CT showed that metastatic lesions obviously increased within 3 mo, and components of juvenile yellow granuloma, Rosai-Dorfman disease, and histiocytic sarcoma were found in the pathological examination. The prognosis of juvenile yellow granuloma and Rosai-Dorfman disease is relatively favorable[11,12]. On the other hand, the median overall survival for histiocytic sarcoma is only 6 mo and the rate of survival does not improve over time[13]. Seven cases of malignant histiocytosis associated with MGCTs available in the literature all died or were lost to follow-up within 5 mo after diagnosis of malignant histiocytosis[1,7,8]. The information above suggests a dismal outcome for our patient.

Due to the short survival time of MGCT associated with malignant histiocytosis, little experience in treatment can be acquired from the literature. Two cases diagnosed as malignant histiocytosis accepted chemotherapy based on cisplatin, bleomycin and etoposide[1], and the treatment of another one was not described[7]. Two cases with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) accepted chemotherapy aimed at HLH (no exact details)[8] and two cases with histiocytic sarcoma did not accept treatment[3]. Six of the seven patients above died, and the other was lost to follow-up. Considering that few patients benefit from HSCT, some of them were recommended to accept HSCT but none were given the opportunity, for different reasons. The case we presented did not accept HSCT, but was still in good condition on the last follow-up, 10 mo since the diagnosis of malignant histiocytosis. That may be associated with the relatively atypical and lesser components of histiocytic sarcoma, and perhaps suggests a sensitive response to vincristine and cytarabine.

Physicians who care for patients with MGCT should be aware of the possibility of associated hematologic malignancies, especially in those patients with nonseminomatous MGCT. Regular monitoring with blood routine and imaging examinations during the 1st year of MGCT diagnosis is recommended to detect associated hematologic disorders. Multiple parts of the tumor may be involved in different stages of evolution, and clinicians should select suitable sites of sampling according to the characteristics of the patient, and take samples from multiple sites when necessary.

All of the authors would like to express their gratitude to the patient and his parents.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cristaldi PMF, Italy; Govindarajan KK, India A-Editor: Yao QG, China S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Ikdahl T, Josefsen D, Jakobsen E, Delabie J, Fosså SD. Concurrent mediastinal germ-cell tumour and haematological malignancy: case report and short review of literature. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:466-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nichols CR, Hoffman R, Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Wheeler LA, Garnick MB. Hematologic malignancies associated with primary mediastinal germ-cell tumors. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:603-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Song SY, Ko YH, Ahn G. Mediastinal germ cell tumor associated with histiocytic sarcoma of spleen: case report of an unusual association. Int J Surg Pathol. 2005;13:299-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Taylor J, Donoghue MT, Ho C, Petrova-Drus K, Al-Ahmadie HA, Funt SA, Zhang Y, Aypar U, Rao P, Chavan SS, Haddadin M, Tamari R, Giralt S, Tallman MS, Rampal RK, Baez P, Kappagantula R, Kosuri S, Dogan A, Tickoo SK, Reuter VE, Bosl GJ, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Solit DB, Taylor BS, Feldman DR, Abdel-Wahab O. Germ cell tumors and associated hematologic malignancies evolve from a common shared precursor. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:6668-6676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Su Y, Ma XL. Clinical features and prognosis of mediastinal germ cell tumor complicated with hematological malignancy. Zhongguo Xiaoer Xueye Yu Zhongliu Zazhi. 2020;25:373-376. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Nichols CR, Roth BJ, Heerema N, Griep J, Tricot G. Hematologic neoplasia associated with primary mediastinal germ-cell tumors. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1425-1429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hartmann JT, Nichols CR, Droz JP, Horwich A, Gerl A, Fossa SD, Beyer J, Pont J, Fizazi K, Einhorn L, Kanz L, Bokemeyer C. Hematologic disorders associated with primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:54-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sowithayasakul P, Sinlapamongkolkul P, Treetipsatit J, Vathana N, Narkbunnam N, Sanpakit K, Buaboonnam J. Hematologic Malignancies Associated With Mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors: 10 Years' Experience at Thailand's National Pediatric Tertiary Referral Center. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;40:450-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ng WK, Lam KY, Ng IO. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis: possible association with malignant germ cell tumour. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:963-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saito A, Watanabe K, Kusakabe T, Abe M, Suzuki T. Mediastinal mature teratoma with coexistence of angiosarcoma, granulocytic sarcoma and a hematopoietic region in the tumor: a rare case of association between hematological malignancy and mediastinal germ cell tumor. Pathol Int. 1998;48:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, Horne A, Haroche J, Donadieu J, Requena-Caballero L, Jordan MB, Abdel-Wahab O, Allen CE, Charlotte F, Diamond EL, Egeler RM, Fischer A, Herrera JG, Henter JI, Janku F, Merad M, Picarsic J, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Rollins BJ, Tazi A, Vassallo R, Weiss LM; Histiocyte Society. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 970] [Article Influence: 107.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Abla O, Jacobsen E, Picarsic J, Krenova Z, Jaffe R, Emile JF, Durham BH, Braier J, Charlotte F, Donadieu J, Cohen-Aubart F, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Allen C, Whitlock JA, Weitzman S, McClain KL, Haroche J, Diamond EL. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and clinical management of Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease. Blood. 2018;131:2877-2890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 52.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kommalapati A, Tella SH, Durkin M, Go RS, Goyal G. Histiocytic sarcoma: a population-based analysis of incidence, demographic disparities, and long-term outcomes. Blood. 2018;131:265-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |