Published online Jul 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.7097

Peer-review started: December 17, 2021

First decision: January 26, 2022

Revised: January 30, 2022

Accepted: May 22, 2022

Article in press: May 22, 2022

Published online: July 16, 2022

Processing time: 199 Days and 12.3 Hours

Hepatic solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare neoplasm. Up to now, only 90 cases have been reported in the English language literature. This report describes a case of SFT of the liver misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma.

A 42-year-old male had a two-year history of a gradually enlarging intrahepatic nodule. The preoperative imaging revealed a mass with a size of 2.7 cm × 2.3 cm located in the segment IV of the liver. The patient was subjected to the resection of the segment IV, such as the medial segment of the left lobe of the liver. The histological examination of the mass showed various spindled cells irregularly arranged in the stroma. The immunohistochemistry of this mass revealed a positive staining for CD34 and STAT6. The history of intracranial tumor and postoperative pathological results led to the diagnosis of SFT of the liver (SFTL) due to a metastasis from the brain.

SFTL is an uncommon mesenchymal neoplasm that can be easily overlooked or misdiagnosed. The best treatment choice is the complete surgical resection of the mass. A regular follow-up after the surgery should be performed due to the poor prognosis of metastatic or recurrent SFT.

Core Tip: This article describes a rare case of liver mesenchymal neoplasm preoperatively misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma. The postoperative pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor. A metastatic lesion was primarily considered due to the history of intracranial hemangiopericytoma. Its radiological features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies are also discussed.

- Citation: Xie GY, Zhu HB, Jin Y, Li BZ, Yu YQ, Li JT. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(20): 7097-7104

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i20/7097.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i20.7097

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm was first reported by Klemperer and Rabin in 1931[1]. SFT and hemangiopericytoma are the same disease according to the 2016 classification of the World Health Organization[2]. It can occur anywhere in the body, but solitary fibrous tumors of the liver (SFTL) are rare, only 90 cases reported in the literature. Thus, this report describes an additional case. The clinical symptoms and radiological features of SFTL are nonspecific. Thus, surgical resection is the preferred treatment for SFT and the diagnosis is mainly based on the results of histopathology and immunohistochemistry of the surgical specimen[3]. The diffuse nuclear STAT6 expression is the main characteristic of SFT allowing its diagnosis[4]. Patient age, tumor size, mitotic activity and tumor necrosis represent the risk stratification models for SFT to predict the risk of metastasis[5]. This report describes a case of SFTL in a 42-year-old male initially misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

A 42-year-old male patient was admitted to the hospital with a two-year history of a gradually enlarging intrahepatic nodule.

A space-occupying lesion of 1 cm in diameter was found in the liver of the patient by physical examination 2 years earlier, and outpatient doctors suggested periodic monitoring. The mass has recently become larger, reaching 2.7 cm in diameter, leading to occasional pain in the right upper abdomen, but without discomfort such as bloating, nausea, vomiting, or fatigue.

The patient had a history of cranial meningioma seven years earlier, which was subjected to surgery and the postoperative pathological diagnosis revealed a hemangiopericytoma. Adjuvant radiotherapy was performed after the surgery. In addition, the patient had a history of chronic hepatitis B infection for 30 years. An antiviral treatment with nucleotide analogue entecavir 0.5 mg/d was administered to inhibit the HBV DNA.

The patient had no personal and family history related to cancer.

Physical examination was unremarkable, the liver and spleen were not palpable.

The patient was positive for HbsAg, HbeAb and HbcAb. HBV-DNA was lower than 30 IU/mL. The level of tumor markers was unremarkable, including alpha-fetoprotein 2.2 ng/mL (normal range < 20 ng/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen 1.0 ng/mL (normal range < 5 ng/mL), and cancer antigen 19-9 2.9 U/mL (normal range < 37 ng/mL). Liver and kidney functions were within the normal range, as same as blood routine examination, blood biochemistry and coagulation function.

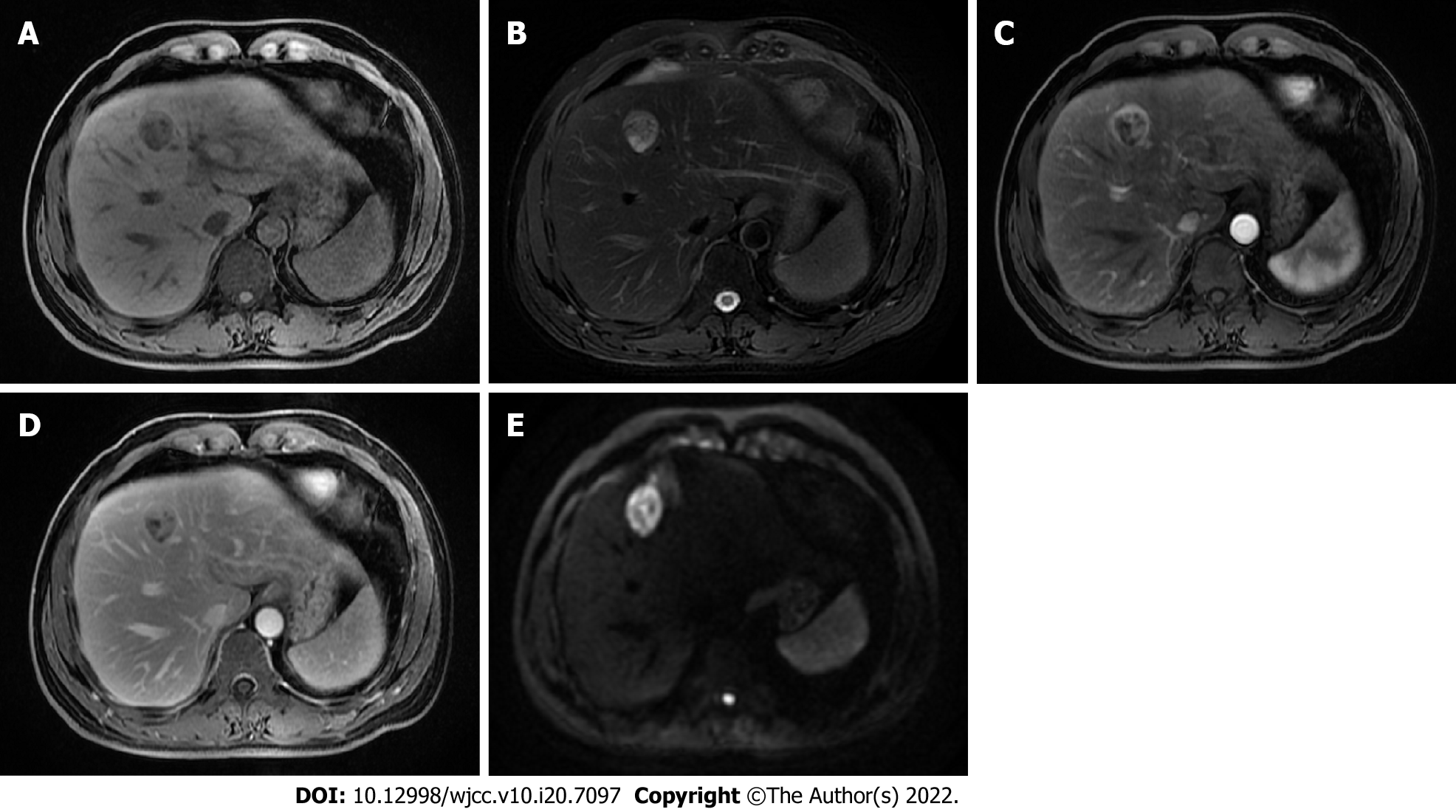

The abdominal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver revealed a 2.7 cm × 2.3 cm mass in the segment IV of the liver. The mass was slightly hypointense on the T1-weighted sequences (Figure 1A) and isointense to hyperintense on the T2-weighted sequences (Figure 1B). The use of a contrast agent revealed that the mass showed a significant arterial phase enhancement (Figure 1C), and a weakened of portal vein phase enhancement (Figure 1D). The diffusion weighted imaging revealed a restriction to diffusion (Figure 1E). Computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed no lung parenchymal abnormality. In addition, the imaging of spleen, pancreas, and gallbladder was normal.

According to the radiologic features, the diagnosis prior to surgery was HCC.

The patient was diagnosed with SFTL after surgery due to a metastasis from the brain.

After the relevant examinations, the patient was subjected to the resection of the segment IV of the liver, the medial segment of the left lobe of the liver, in June 2021. No cirrhosis or ascites was found during the intraoperative exploration. The ultrasonography showed that the tumor was in the segment IV of the liver, and the tumor was entirely resected under laparoscopy. The patient recovered well after postoperative anti-infectives, analgesia, acid suppression, and other supportive treatment.

At a macroscopic level, the size of the resected mass was 24 mm × 27 mm × 20 mm (Figure 2). The boundary between the tumor and the surrounding tissue was clear, and the section of the surgical specimens was grey to white with local hemorrhage and necrosis. No tumor tissue was present in the surgical margins. At a microscopic level, the tumor contained randomly arranged spindle cells, with abundant stromal collagen (Figure 3A). The immunohistochemical analysis showed that the tumor cells were positive for CD34 (Figure 3B), STAT6 (Figure 3C), and the cell proliferation marker Ki-67, but negative for smooth muscle actin, as well as for the tumor markers HMB45, Melan-A, CK (AE1/AE3), CAM5.2, EMA, PR, CD117, and DOG-1. The Ki67 Labeling index was 10%-15% (Figure 3D). Based on these clinical and histological findings, SFT was diagnosed. The patient recovered uneventfully after surgery. Two months after the liver surgery, positron emission tomography-CT was performed, revealing no local recurrence, pulmonary or bone metastases. At present, 6 mo have relapsed since the surgery and the patient is still fine with no evidence of tumor recurrence (Figure 4).

SFT is a rare neoplasm of mesenchymal origin, most commonly originating from the pleura[6]. However, it can occur in multiple parts of the body, including the meninges[7], spine[8], pancreas[9], pelvis[10], adrenal gland[11] and liver[12]. SFT of the liver is extremely rare, 84 cases reported in the literature from 1958 to 2016 according to a review by Chen and Slater[13]. However, only 6 cases with SFTL were reported in the literature in recent five years, and our patient is the seventh (Table 1). The average age of the patients (34 males, 51 females, and 6 unknown) is 57.1 (range 16-87). SFTL occurs more frequently in females (ratio 1.5:1). The mean tumor diameter is 16.0 cm (range 1.5-35 cm). The clinical symptoms of SFTL are nonspecific. It is discovered by chance during a routine examination in most patients[14]. When symptoms appear, they are caused by mass effects or paraneoplastic syndrome, and include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, weight loss, fatigue and hypoglycemia[15,16]. Similar to this evidence, our patient had occasional pain in the right upper abdomen. Tumor serum markers in SFTL are non-specific, and also our patient showed an unremarkable expression of tumor markers.

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Sex | Chief complaint | Size (cm) | Treatment | Immunohistochemistry (+) | Follow-up |

| Dey et al[14] | 56 | F | Abdominal pain | 20 | Resection | Vimentin, CD34, BCl2 | 6 mo |

| Esteves et al[20] | 68 | F | Incidental | 13.5 | Resection | STAT6, CD34 | 37 mo |

| Yugawa et al[23] | 49 | F | Abdominal bloating | 13.3 | Resection | STAT6, Vimentin | 12 mo |

| Mao et al[22] | 60 | F | Upper back pain | 3.5 | Resection | CD34, STAT6 | 24 mo |

| Nam et al[30] | 45 | M | Incidental | 2.8 | Without intervention | CD34, CD99 | N/A |

| Roman et al[21] | 75 | F | Incidental | 30 | Resection | CD34, STAT6, Bcl2, CD99, caldesmon, focally calponin | N/A |

| Present case | 42 | M | Incidental | 2.7 | Resection | CD34, STAT6 | 6 mo |

The radiological features of SFT are also non-specific[17]. The abdominal ultrasound may display a heterogeneous mass with well-defined margins. The tumor could display a hyperechoic or hypoechoic mass with or without calcification[18]. Contrast-enhanced CT reveals irregular enhancement in arterial phase and portal venous phase[19]. MRI reveals tumors of low-to-intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and heterogeneous mixtures of low-to-high signal intensity on T2-weighted images[20]. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish SFT from other tumors based only on imaging features, including HCC, fibrosarcoma, hemangioma, leiomyomas, or inflammatory pseudotumor[21]. Our case was misdiagnosed as liver cancer based on the images of the abdominal ultrasound and MRI.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry are the golden standard for SFT diagnosis. At a microscopic level, classical architectural patterns can be seen as a random arranged spindled to ovoid cells, with abundant stromal collagen[22]. The typical SFT of the liver is immunoreactive for CD34, CD99, vimentin and BCL-2. The staining of CD34 is useful to distinguish SFT from other spindle cell neoplasms. However, a small percentage (5%-10%) of classical SFT is immunohistochemically negative for CD34[23]. Recent studies confirm that the NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene has excellent sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of SFT than other conventional immunohistochemical markers[24]. The diffuse nuclear STAT6 expression by immunohistochemical detection represents the marker for the diagnosis of SFT. Our patient was immunohistochemically positive for CD34 and STAT6, which allowed the final correct diagnosis. Although STF is usually benign, some patients experienced an aggressive or malignant behavior of this tumor, as previously reported[25]. Traditional criteria for malignant SFT include nuclear pleomorphism, tumor hemorrhage or necrosis, cellular atypia, large tumor size (> 10 cm), and mitotic changes (≥ 4 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields)[26]. Our patient met one of the five criteria (necrosis/hemorrhage), indicating a potential malignant tumor. The clinical course of SFT is difficult to predict based on histological characteristics. Demicco et al[5] proposed an updated risk stratification model for SFT to predict the risk of metastasis, incorporating patient age, tumor size, mitotic activity and tumor necrosis. This model allows a better evaluation of the tumor to make an individualized treatment program.

As regards the treatment, complete surgical resection is the preferred treatment strategy for SFT. The prognosis after complete resection is significantly better than that after incomplete resection[21]. Adjuvant radiotherapy is often recommended after surgery in case of meningeal SFT. A retrospective study revealed that adjuvant radiotherapy is not beneficial to the overall survival, but it is used for a better local control[27]. Other optional treatments are recommended for unresectable tumors, including transarterial chemoembolization, chemotherapy, and antiangiogenic drugs. However, SFT is insensitive to conventional chemotherapy, and no specific clinical trials have been reported before[20]. Some clinical studies used multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor for aggressive SFT, including sunitinib, sorafenib, and pazopanib, achieving promising results in some cases[4,28]. Our patient underwent complete resection with a tumor-free margin. We want to clarify whether this liver tumor was a metastatic focus from the brain. However, the cranial tumor specimen was not available because the operation was performed in France seven years ago. The patient does not have liver cirrhosis, and the SFTL occurred after intracranial hemangiopericytoma. The history of our patient and imaging findings revealed that SFTL was most likely a metastasis from the original brain tumor rather than a primary tumor in the liver.

The mechanisms of solitary liver metastasis from meningeal SFT might be associated with NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion and pan-TRK expression. Several studies showed that NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion can evaluate the metastasis of SFT. Singh et al[29] reported NAB2ex6-STAT6ex16 fusion detected in malignant SFT of the liver, and the original brain hemangiopericytoma showed the same fusion, suggesting a metastatic tumor rather than a primary tumor in the liver. Moreover, Barthelmeß et al[30] showed that NAB2ex6-STAT6ex16/17 fusion is correlated with a more aggressive tumor phenotype and high recurrence rate in SFTs. Pan-TRK expression is closely related to tumor recurrence or progression in SFT patients, and these patients have poor outcomes[31]. In the future, the mechanisms of solitary liver metastasis from meningeal SFT should be explored more in details.

When a patient has a history of extrahepatic SFT and a liver tumor is found, clinicians should monitor whether it is a metastatic SFT or a primary liver tumor. A fine-needle liver biopsy can be used to confirm the diagnosis if the tumor cannot be surgically removed[32]. The prognosis of metastatic SFT is unclear, and a long-term follow-up is recommended. Studies with more cases are needed to elucidate the factors influencing the prognosis and the management of metastatic SFT in the future.

In conclusion, a remarkable rare intrahepatic tumor misdiagnosed as HCC was described, and the postoperative diagnosis was SFT. Since the clinical symptoms and radiological features are non-specific, it is difficult to diagnose this tumor without histological and immunohistochemical evaluation. Complete surgical resection is the standard approach used in the management of SFT. The tumor may cause a potential recurrence or metastasis; thus, a long-term follow-up of patients with SFT is recommended.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Casà C, Italy; Tajiri K, Japan S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chang KL

| 1. | Klemperer P, Coleman BR. Primary neoplasms of the pleura. A report of five cases. Am J Ind Med. 1992;22:1-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10993] [Cited by in RCA: 10806] [Article Influence: 1200.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Soussan M, Felden A, Cyrta J, Morère JF, Douard R, Wind P. Case 198: solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Radiology. 2013;269:304-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Martin-Broto J, Mondaza-Hernandez JL, Moura DS, Hindi N. A Comprehensive Review on Solitary Fibrous Tumor: New Insights for New Horizons. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Demicco EG, Wagner MJ, Maki RG, Gupta V, Iofin I, Lazar AJ, Wang WL. Risk assessment in solitary fibrous tumors: validation and refinement of a risk stratification model. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:1433-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lu C, Ji Y, Shan F, Guo W, Ding J, Ge D. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: an analysis of 13 cases. World J Surg. 2008;32:1663-1668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Claus E, Seynaeve P, Ceuppens J, Vanneste A, Verstraete K. Intracranial Solitary Fibrous Tumor. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2017;101:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang YW, Xiao Q, Zeng JH, Deng L. Solitary fibrous tumor of the lumbar spine resembling schwannoma: a case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Estrella JS, Wang H, Bhosale PR, Evans HL, Abraham SC. Malignant Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Pancreas. Pancreas. 2015;44:988-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Prunty MC, Gaballah A, Ellis L, Murray KS. Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Pelvis Involving the Urinary Bladder. Urology. 2018;117:27-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gebresellassie HW, Mohammed Y, Kotiso B, Amare B, Kebede A. A giant solitary fibrous tumor of the adrenal gland in a 13-year old: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13:246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vennarecci G, Ettorre GM, Giovannelli L, Del Nonno F, Perracchio L, Visca P, Corazza V, Vidiri A, Visco G, Santoro E. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:341-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen N, Slater K. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver-report on metastasis and local recurrence of a malignant case and review of literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dey B, Gochhait D, Kaushal G, Barwad A, Pottakkat B. Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Liver: A Rare Tumor in a Rarer Location. Rare Tumors. 2016;8:6403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bejarano-González N, García-Borobia FJ, Romaguera-Monzonís A, García-Monforte N, Falcó-Fagés J, Bella-Cueto MR, Navarro-Soto S. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Case report and review of the literature. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:633-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nath DS, Rutzick AD, Sielaff TD. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W187-W190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Changku J, Shaohua S, Zhicheng Z, Shusen Z. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: retrospective study of reported cases. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:132-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shu Q, Liu X, Yang X, Guo B, Huang T, Lei H, Peng F, Su S, Li B. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2305-2310. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Belga S, Ferreira S, Lemos MM. A rare tumor of the liver with a sudden presentation. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:e14-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Esteves C, Maia T, Lopes JM, Pimenta M. Malignant Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Liver: AIRP Best Cases in Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics. 2017;37:2018-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Roman J, Vávra P, Vávrová M, Židlík V, Pelikán A. A giant solitary fibrous tumour of the liver: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2021;1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mao M, Zhou L, Huang C, Yan X, Hu S, Yin H, Zhao Q, Song D. Case Report: A Malignant Liver and Thoracic Solitary Fibrous Tumor: A 10-Year Journey From the Brain to the Liver and the Spine. Front Surg. 2020;7:570582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yugawa K, Yoshizumi T, Mano Y, Kurihara T, Yoshiya S, Takeishi K, Itoh S, Harada N, Ikegami T, Soejima Y, Kohashi K, Oda Y, Mori M. Solitary fibrous tumor in the liver: case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep. 2019;5:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang SC, Huang HY. Solitary fibrous tumor: An evolving and unifying entity with unsettled issues. Histol Histopathol. 2019;34:313-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rouy M, Guilbaud T, Birnbaum DJ. Liver Solitary Fibrous Tumor: a Rare Incidentaloma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:852-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. A clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 953] [Cited by in RCA: 845] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Haas RL, Walraven I, Lecointe-Artzner E, van Houdt WJ, Scholten AN, Strauss D, Schrage Y, Hayes AJ, Raut CP, Fairweather M, Baldini EH, Gronchi A, De Rosa L, Griffin AM, Ferguson PC, Wunder J, van de Sande MAJ, Krol ADG, Skoczylas J, Brandsma D, Doglietto F, Sangalli C, Stacchiotti S. Management of meningeal solitary fibrous tumors/hemangiopericytoma; surgery alone or surgery plus postoperative radiotherapy? Acta Oncol. 2021;60:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Riedel RF. Anti-angiogenic therapy for malignant solitary fibrous tumour: validation through collaboration. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:14-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Singh N, Collingwood R, Eich ML, Robinson A, Varambally S, Al Diffalha S, Harada S. NAB2-STAT6 Gene Fusions to Evaluate Primary/Metastasis of Hemangiopericytoma/Solitary Fibrous Tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156:906-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Barthelmeß S, Geddert H, Boltze C, Moskalev EA, Bieg M, Sirbu H, Brors B, Wiemann S, Hartmann A, Agaimy A, Haller F. Solitary fibrous tumors/hemangiopericytomas with different variants of the NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion are characterized by specific histomorphology and distinct clinicopathological features. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1209-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Salguero-Aranda C, Martínez-Reguera P, Marcilla D, de Álava E, Díaz-Martín J. Evaluation of NAB2-STAT6 Fusion Variants and Other Molecular Alterations as Prognostic Biomarkers in a Case Series of 83 Solitary Fibrous Tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Debs T, Kassir R, Amor IB, Martini F, Iannelli A, Gugenheim J. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1291-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nam HC, Sung PS, Jung ES, Yoon SK. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver mimicking malignancy. Korean J Intern Med. 2020;35:734-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |