Published online Jan 14, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i2.709

Peer-review started: July 31, 2021

First decision: October 22, 2021

Revised: November 2, 2021

Accepted: December 10, 2021

Article in press: December 10, 2021

Published online: January 14, 2022

Processing time: 164 Days and 12.6 Hours

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which accounts for about approximately 30% to 40% of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, is the most common type and is a class of aggressive B-cell lymphomas. However, diffuse large B-cell lymphomas primary to the adrenal gland are rare.

A 73-year-old man was admitted with abdominal pain and fatigue. After admission, enhanced adrenal computed tomography indicated irregular masses on both adrenal glands, with the larger one on the left side, approximately 8.0 cm × 4.3 cm in size. The boundary was irregular, and surrounding tissues were compressed. No obvious enhancement was observed in the arterial phase. Resection of the left adrenal gland was performed. Pathological diagnosis revealed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. After surgery, the patient received R-CHOP immunochemotherapy. During the fourth immunochemotherapy, patient condition deteriorated, and he eventually died of respiratory failure.

R-CHOP is the conventional immunochemotherapy for primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Surgery is mainly used to diagnose the disease. Hence, the ideal treatment plan remains to be confirmed.

Core Tip: Primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a rare disease with no consistent treatment standards. The R-CHOP regimen is the conventional immunochemotherapy regimen for this disease. We report a case of surgery combined with immunochemotherapy; however, immunochemotherapy was ineffective and the patient eventually died of respiratory failure. Therefore, the optimal treatment of primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma remains to be further explored.

- Citation: Fan ZN, Shi HJ, Xiong BB, Zhang JS, Wang HF, Wang JS. Primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with normal adrenal cortex function: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(2): 709-716

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i2/709.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i2.709

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which accounts for approximately 30% to 40% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, is the most common type among the aggressive B-cell lymphomas[1]. Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas that originate in the adrenal glands are rare. Primary adrenal DLBCL (PADLBCL) is a highly malignant tumor with no specific clinical manifestations and thus, requires early diagnosis and treatment. The main manifestations of PADLBCL in patients are abdominal pain, fatigue, fever, night sweats, weight loss, and adrenal cortex insufficiency. Imaging often shows adrenal occupancy; however, clear diagnosis requires adrenal biopsy or postoperative specimen examination. To date, no unified treatment standard exists, and PADLBCL is mainly treated with immunochemotherapy, and yet has poor prognosis. Currently, there have been only few reports on PADBCLD. We here report a case of bilateral PADLBCL. Combined with related literature and our observations, we have analyzed the clinical, imaging, and pathological characteristics of PADLBCL, and discussed the current related treatment methods and prognostic factors, with an aim to deepen the understanding of this disease.

A 73-year-old man was admitted in our hospital with abdominal pain and fatigue lasting 1 mo.

One month before his admission, the patient developed persistent abdominal pain without obvious incentives, such as tolerable dull pain on the left side, without abdominal distension, lethargy, cold sensitivity, itchy skin, and change in skin color, among other symptoms. Since the start of the symptoms, the patient had poor appetite and spirit, and lost more than 10 kg weight.

The patient had no history of surgery, trauma, or other diseases.

There was no history of hereditary diseases. No family members had similar symptoms.

The physical examination of the patient was unremarkable.

Routine blood tests, liver and kidney function test, blood coagulation function test, hormone-related examination, and tumor marker analysis showed no obvious abnormalities. In addition, the level of serum potassium was normal.

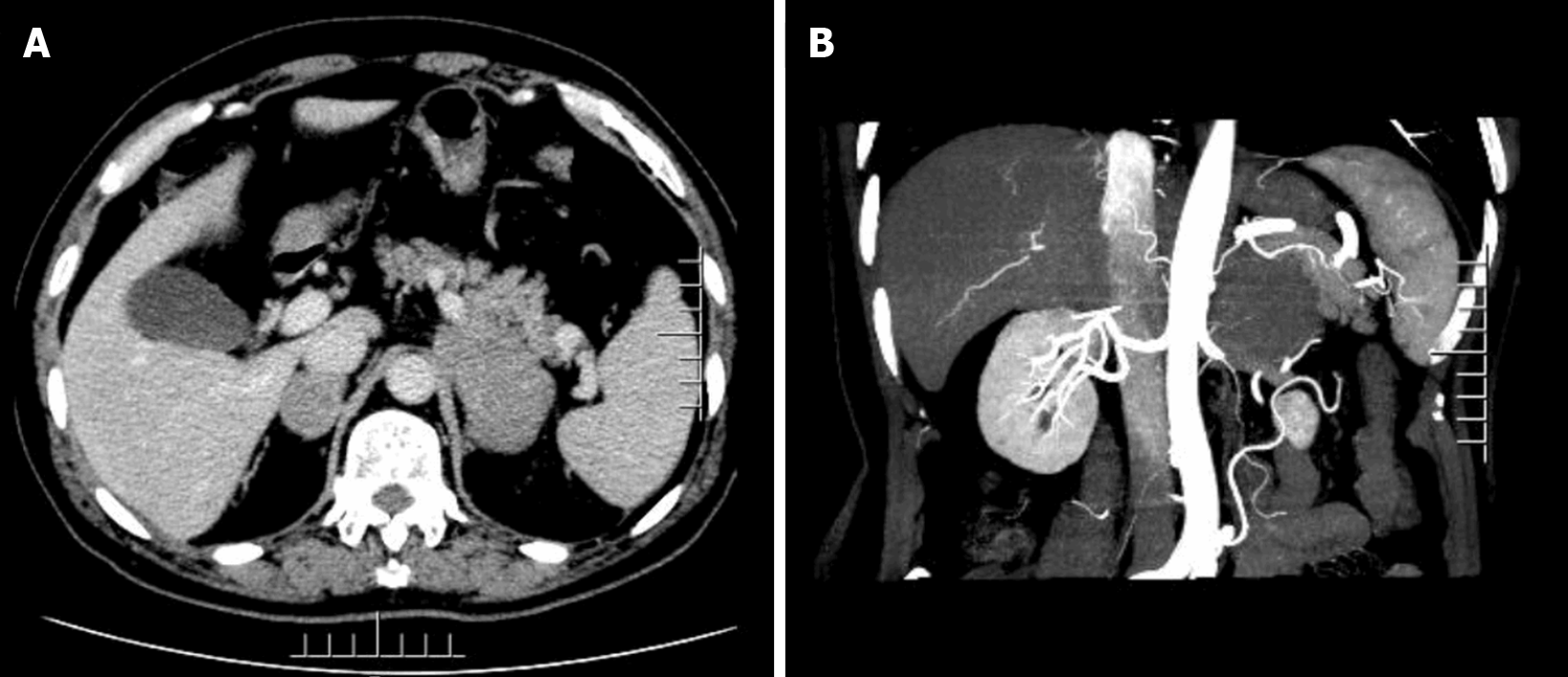

The adrenal enhancement computed tomography (CT) scan showed the presence of irregular masses in the adrenal glands on both sides, with the larger one being located on the left side. Its size was approximately 8.0 cm × 4.3 cm, its border was irregular, and the surrounding tissues were compressed. We did not observe any obvious enhancement in the arterial phase, nor any obvious swollen lymph nodes were noted later on (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed with non-GCB primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

We performed a left adrenalectomy under laparoscopic surgery. During the surgery, an irregular mass was observed in the left adrenal area. The mass was strongly adhered to the upper pole of the left kidney, and it pressurized the left kidney in forward and downward direction. No detectable lymph node enlargement was observed. The upper pole of the left kidney was damaged during the laparoscopic separation of the mass, so the wound surface was sutured continuously with 3-0 absorbable suture. After the separation of the tumor from the upper pole of the left kidney, due to excessive blood on the wound surface and compromised visibility, the tumor vessels were perturbed during the operation leading to the rupture of associated blood vessels. Due to the excessive blood loss, the laparoscopic surgery was reallocated to open abdominal surgery. The intraoperative blood loss was approximately 1300 mL, and blood transfusion was prescribed to overcome the loss.

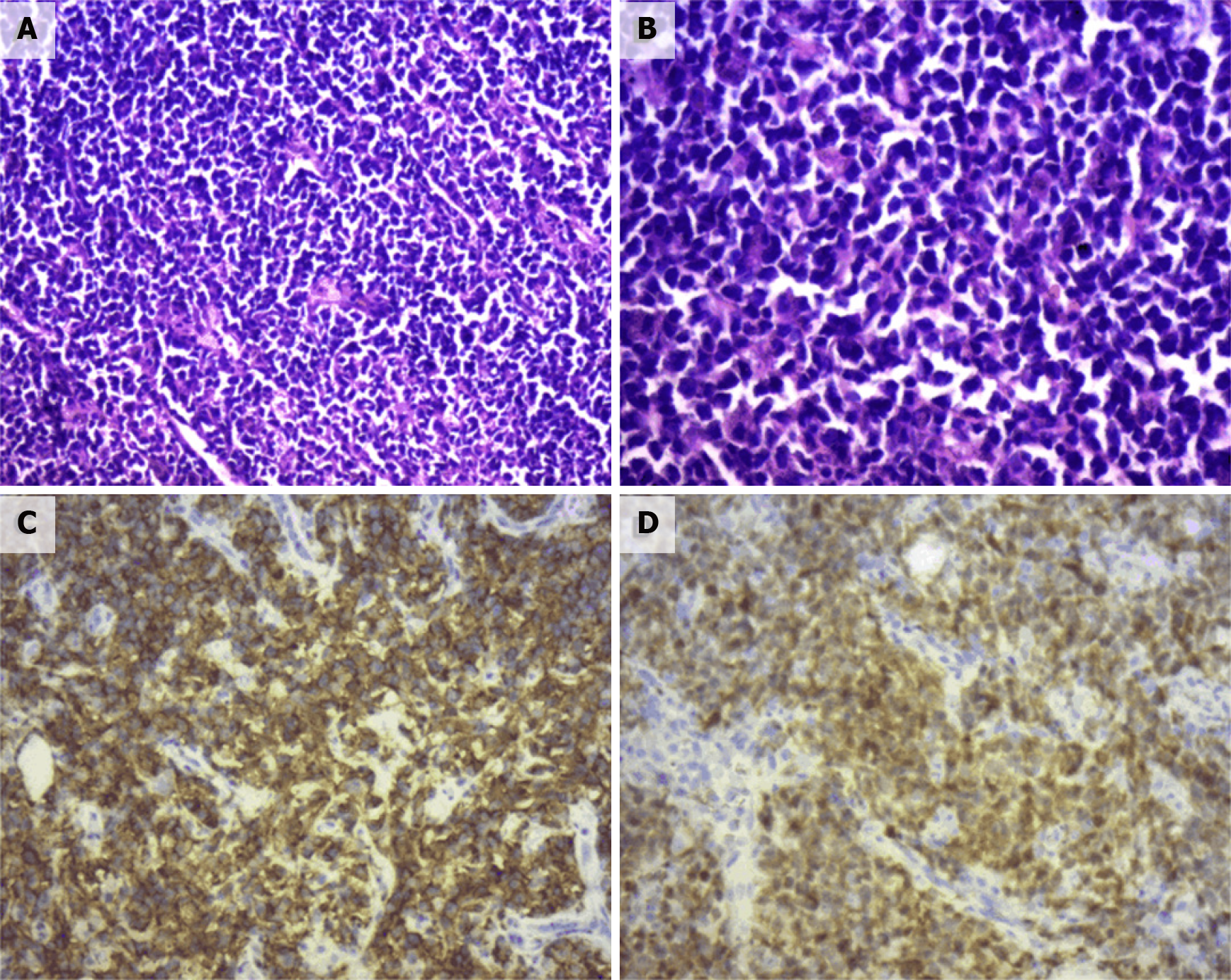

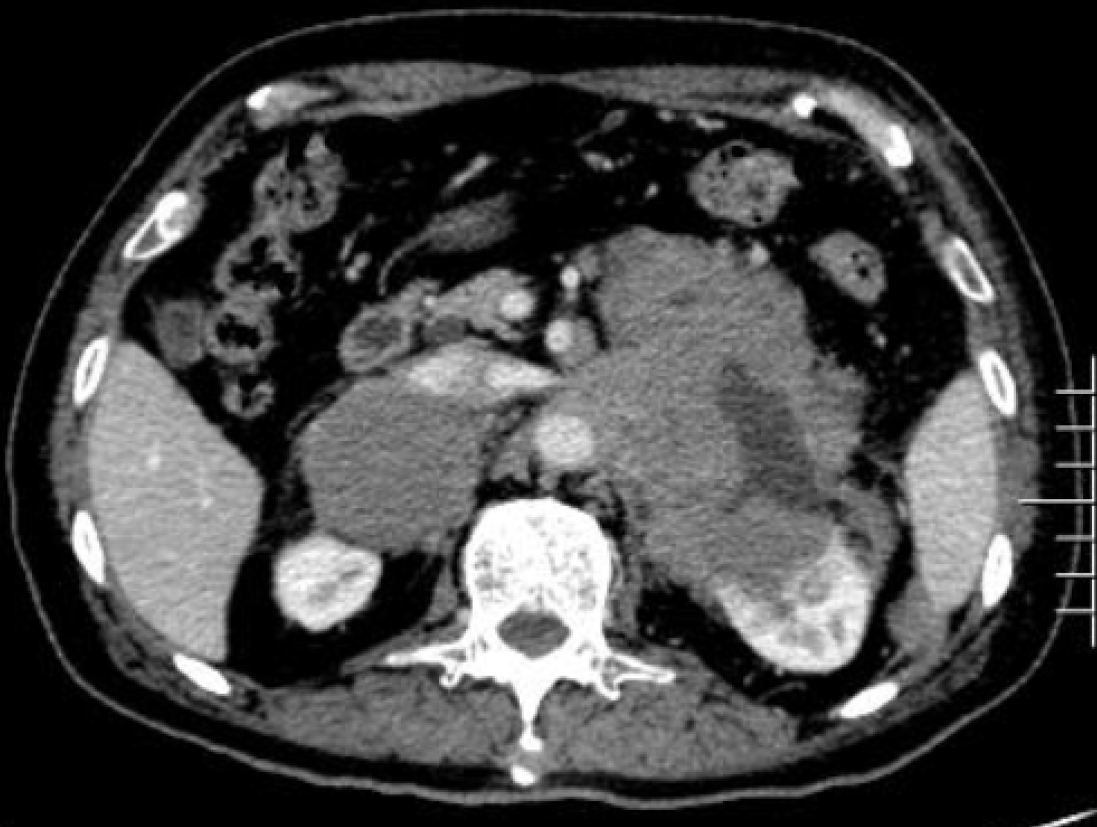

Pathological diagnosis identified the presence of non-GCB diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the left adrenal gland. Light microscopy observation revealed diffuse infiltration and growth of tumor cells in normal adrenal tissues. Tumor cells were composed of medium to large lymphoid cells. Most cells were round or oval in shape, double chromotropic or basophilic, containing less cytoplasm and larger nuclei (Figure 2A and B). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed tumor cells to be CD19 (+), CD20 (+), PAX-5 (+), CD79a (+), Ki67 (70%), CD43 (+), MUM1 (+), bcl-6 (+), CD45RO (focus +), CD3 (scattered +), cyclinD1 (-), CD10 (-), and CD30 (-) (Figure 2C and D). After the pathological diagnosis was confirmed, the patient was immediately notified telephonically. However, due to the patient's personal reasons, the return visit was delayed, and the patient returned to the hospital for further treatment a month later. Re-examination of the patient with abdominal enhanced CT 1 mo after the surgery revealed multiple soft tissue shadows in the retroperitoneum on both sides, uneven enhancement, and a left retroperitoneal soft tissue mass protruding into the kidney (Figure 3). Subsequently, the patient underwent four immunochemotherapy sessions at the hematology department of our hospital. The immunochemotherapy regimen was R-CHOP (rituxan 600 mg d1; cyclophosphamide 1.2 g d1; liposomal adriamycin 40 mg d1; vincristine 4 mg d1; and prednisone acetate 100 mg d1-d5). During fourth immunochemotherapy session, the patient developed a severe pulmonary infection, and sputum culture suggested infection by fungi and multidrug-resistant bacteria. The patient coughed sputum, and his body temperature fluctuated between 37 and 38 °C, and therefore, he was treated with sensitive antibiotics. Chest CT indicated diffuse patchy fuzzy shadows in both lungs, indicating inflammation. Hematologists did not rule out lung damage caused by immunochemotherapy drugs, and symptomatic treatment was continued. On January 22, 2019, the patient was required to receive 9 L/min oxygen by mask, with his oxygen saturation being 85%. Re-examination of the chest CT revealed further aggravation of the infection. Antibiotic treatment and oxygen therapy were strengthened further, with the oxygen saturation of the patient reaching 92%. Subsequent treatment continued according to patient’s symptoms. However, at 03:37 on January 27, 2019, his oxygen saturation dropped to 60%. His oxygen saturation could not be monitored further, his heart rate decreased gradually, and his both pupils were dilated. The patient was declared dead and the cause of his death was determined as respiratory failure.

PADLBCL is a rare disease. To date, only more than 100 cases have been reported in the PubMed database[2]. PADLBCL mainly affects middle-aged and elderly men, with an average age of more than 60 years, and a male-to-female sex ratio of 2.93:1. In addition, the bilateral involvement of adrenal glands is common[3]. At present, the etiology and pathogenesis of PADLBCL remain unclear and have been suggested to be related to autoimmune deficiency, HIV, or EBV infections[4]. There are two viewpoints regarding the pathogenesis of PADLBCL. First, it may be related to the genetic predisposition of patients, such as mutations in the p53 and c-kit encoding genes as reported in adrenal lymphomas[5]. The second view suggests the initial occurrence of lymphoma outside the adrenal glands followed by their subsequent affliction, with chemokines and microRNAs driving this process, which can explain the bilateral involvement of the adrenal glands[6].

The clinical manifestations of PADLBCL lack specificity. Most patients experience pain around the waist and abdomen as the first symptom, accompanied by fatigue, fever, and night sweats[7]. When the bilateral adrenal glands are involved, most patients can have symptoms of adrenal insufficiency, manifested as skin pigmentation, hypotension, and fever[8]. In addition, PADLBCL involves the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, leading to adrenal insufficiency[9]. Therefore, for PADLBCL with adrenal insufficiency, systematic endocrine assessment should be performed. As our patient had PADLBCL with normal adrenal cortex function, his case relied on imaging examinations, providing lesser diagnostic information from the clinical symptoms and signs.

Imaging is an indispensable auxiliary diagnostic tool for PADLBCL, and the commonly used clinical examinations include CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[10]. In particular, in CT PADLBCL usually manifests as a low-density adrenal mass, which is moderately enhanced during enhanced scanning, revealing necrosis. In contrast, MRI examination shows a T1 phase low signal and T2 phase high signal. The T1 phase low signal can be distinguished from the T1 phase high signal caused by the hemorrhage of adrenal sarcoma. Besides, FDG-PET is more accurate in evaluating tumors and involved parts for determining extra-adrenal lesions[11,12]. In this case, only a CT examination was performed. However, it is deemed necessary to perform FDG-PET examinations in all PADLBCL cases. Moreover, histopathological examination are required for final diagnosis.

Pathological examination remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of PADLBCL. More specifically, observation under a light microscope reveals the destruction of the adrenal tissue structure, often accompanied by large lamellar necrosis and diffuse infiltration of large lymphocytes. In addition, immunohistochemical analysis of cells often reveals the expression of the CD19, CD20, CD22, CD45, CA79a, and PAX5 markers, and sometimes the expression of CD10 and CD5 proteins. In particular, CD5+ lymphomas are more malignant and associated with a poor prognosis[13]. Immunohistochemistry can also be used to classify the molecular types of PADLBCL. For this purpose, Hans algorithm is most extensively used in routine practice, and it consists of three markers (CD10, Bcl6, MUM1). Based on the combination of these three markers, Hans algorithm could divide DLBCL into two groups (GCB and non-GCB subtype)[14]. Non-GCB type PADLBCL is clinically common and often related to poor prognosis[15]. In recent years, studies have reported that non-GCB patients are often characterized by a higher expression of the proliferation index (Ki-67), with standard R-CHOP immunochemotherapy regimen being less effective in such patients[16]. However, other studies have reported that R-CHOP immunochemotherapy may achieve complete remission of PADLBCL[8].

Combining the medical history of the patient, imaging, pathological morphology, and immunophenotype facilitates the correct diagnosis of PADLBCL; however, attention should be paid to exclude the following possibilities: (1) Secondary lymphoma, that is, that no other lymphomas existed before diagnosis; and (2) Other adrenal tumors including adrenocortical carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, malignant melanoma, and neuroendocrine tumors. Early diagnosis of PADLBCL is generally difficult until the tumor has grown substantially and compresses the peripheral nerves or organs, causing corresponding symptoms or damage to the adrenal tissue and adrenal insufficiency.

Currently, there is no unified treatment regimen for PADLBCL. Most of the therapeutic strategies are developed based on the summary and comparison of the treatment experiences of lymphoma. PADLBCL is usually treated as a systemic disease, and early diagnosis and treatment can significantly prolong the patient’s survival. Since lymphoma is a systemic disease, the invasiveness of PADLBCL is generally extends beyond the visual limit, and it is difficult to achieve complete resection. Therefore, surgery is mainly used to diagnose the disease, and further immunochemotherapy is recommended post-surgery. R-CHOP immunochemotherapy is generally recommended as the first choice, and rituximab combined with second-line chemotherapy, such as bendamustine, DAEPOCH, DHAP, GDP, and GEMOX, is recommended for patients with relapsed/refractory PADLBCL. Patients with relapsed/refractory PADLBCL are known to exhibit a generally rapid progress of the disease and cannot tolerate chemotherapy drugs[17].

As mentioned, PADLBCL has a poor prognosis, Kim et al[18] reported 31 cases of primary adrenal DLBCL with overall 2-year and progression-free survival rates of 68.3% and 51.1%, respectively. A few reports have reported that patients with PADLBCL receiving R-CHOP immunochemotherapy have a better prognosis and can achieve long-term remission or even complete remission[8,19]. It has also been reported that the treatment of surgery, chemotherapy, and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation could retain a patient in remission for 2 years[20]. Many factors, such as the IPI score, non-GCB type, pathological type, treatment of the patient abandonment, and non-standard treatment can affect the prognosis of patients. In addition, adrenal lymphoma is one of the major risk factors for the recurrence of central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma[21]. In the study by Kim et al[18], 13% of patients with adrenal lymphoma had CNS lymphoma recurrence. Therefore, systemic methotrexate or intrathecal injection of methotrexate may be administered during the treatment to prevent the involvement and recurrence of the central nervous system.

In this case, preoperative examination indicated normal adrenal cortex function, which impeded the preliminary diagnosis of PADLBCL by the physician-in-charge. Postoperative pathology indicated non-GCB PADLBCL, and the patient received R-CHOP immunochemotherapy; however, the effect of immunochemotherapy was not beneficial. Possibly, the age of the patient and the impact of the disease and chemothe

The incidence of PADLBCL is low, and clinical symptoms are not typical. It is necessary to improve CT and FDG-PET examinations used for the evaluation of tumor staging, which would be helpful in standardizing treatment. Conventional immunochemotherapy includes the R-CHOP regimen, and surgery is mainly used to diagnose the disease, while the prevention of central nervous system lymphoma also needs to be considered. Thus, the ideal treatment plan needs to be strategized based on further research.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Glumac S, Novo M S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Ayyappan S, Maddocks K. Novel and emerging therapies for B cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Khurana A, Kaur P, Chauhan AK, Kataria SP, Bansal N. Primary Non Hodgkin's Lymphoma of Left Adrenal Gland - A Rare Presentation. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:XD01-XD03. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Babinska A, Peksa R, Sworczak K. Primary malignant lymphoma combined with clinically "silent" pheochromocytoma in the same adrenal gland. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Erçolak V, Kara O, Günaldı M, Usul Afşar C, Bozkurt Duman B, Açıkalın A, Ergin M, Erdoğan S. Bilateral primary adrenal non-hodgkin lymphoma. Turk J Haematol. 2014;31:205-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nakatsuka S, Hongyo T, Syaifudin M, Nomura T, Shingu N, Aozasa K. Mutations of p53, c-kit, K-ras, and beta-catenin gene in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of adrenal gland. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:267-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kadoch C, Treseler P, Rubenstein JL. Molecular pathogenesis of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;21:E1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhou J, Zhao Y, Gou Z. High 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in primary bilateral adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with nongerminal center B-cell phenotype: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim KM, Yoon DH, Lee SG, Lim SN, Sug LJ, Huh J, Suh C. A case of primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma achieving complete remission with rituximab-CHOP chemotherapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:525-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | An P, Chen K, Yang GQ, Dou JT, Chen YL, Jin XY, Wang XL, Mu YM, Wang QS. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma with bilateral adrenal and hypothalamic involvement: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:4075-4083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117:5019-5032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1268] [Cited by in RCA: 1444] [Article Influence: 103.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Radhakrishnan RK, Mittal BR, Reddy Gorla AK, Malhotra P, Bal A, Varma S. Unilateral Primary Adrenal Lymphoma: Uncommon Presentation of a Rare Disease Evaluated Using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography. World J Nucl Med. 2018;17:46-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ram N, Rashid O, Farooq S, Ulhaq I, Islam N. Primary adrenal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Libè R, Giavoli C, Barbetta L, Dall'Asta C, Passini E, Buffa R, Beck-Peccoz P, Ambrosi B. A primary adrenal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma presenting as an incidental adrenal mass. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2006;114:140-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, Müller-Hermelink HK, Campo E, Braziel RM, Jaffe ES, Pan Z, Farinha P, Smith LM, Falini B, Banham AH, Rosenwald A, Staudt LM, Connors JM, Armitage JO, Chan WC. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2826] [Cited by in RCA: 3148] [Article Influence: 143.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Lu TX, Miao Y, Wu JZ, Gong QX, Liang JH, Wang Z, Wang L, Fan L, Hua D, Chen YY, Xu W, Zhang ZH, Li JY. The distinct clinical features and prognosis of the CD10⁺MUM1⁺ and CD10⁻Bcl6⁻MUM1⁻ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Koh YW, Hwang HS, Park CS, Yoon DH, Suh C, Huh J. Prognostic effect of Ki-67 expression in rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone-treated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is limited to non-germinal center B-cell-like subtype in late-elderly patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:2630-2636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Aziz SA, Laway BA, Rangreze I, Lone MI, Ahmad SN. Primary adrenal lymphoma: Differential involvement with varying adrenal function. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:220-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim YR, Kim JS, Min YH, Hyunyoon D, Shin HJ, Mun YC, Park Y, Do YR, Jeong SH, Park JS, Oh SY, Lee S, Park EK, Jang JS, Lee WS, Lee HW, Eom H, Ahn JS, Jeong JH, Baek SK, Kim SJ, Kim WS, Suh C. Prognostic factors in primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of adrenal gland treated with rituximab-CHOP chemotherapy from the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL). J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shirao S, Kuroda H, Kida M, Watanabe H, Matsunaga T, Niitsu Y, Konuma Y, Hirayama Y, Kohda K. [Effective combined modality therapy for a patient with primary adrenal lymphoma]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2006;47:204-209. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Morel P, Van Den Neste E, Salles G, Gaulard P, Reyes F, Lederlin P, Gisselbrecht C. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3975] [Cited by in RCA: 4032] [Article Influence: 175.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Grigg AP, Connors JM. Primary adrenal lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2003;4:154-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |