Published online Jul 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6702

Peer-review started: January 23, 2022

First decision: March 23, 2022

Revised: April 1, 2022

Accepted: May 8, 2022

Article in press: May 8, 2022

Published online: July 6, 2022

Processing time: 151 Days and 19.4 Hours

Endometrial cancer (EC) is a common gynecological malignancy, but metastasis to the abdominal wall is extremely rare. Therefore, an appropriate treatment approach for large metastatic lesions with infection remains a great challenge.

We report the case of a 65-year-old woman who developed abdominal metastasis of endometrioid adenocarcinoma, as defined by International Obstetrics and Gynecology stage II, in which the lesion was complicated by infection. A right hemicolectomy was performed for colon metastasis in relation to her initial gynecological cancer 3 years ago. When admitted to our department, a complete resection of the giant abdominal wall lesion was performed, and a Bard composite mesh was used to reconstruct the abdominal wall. A local flap was used to close the resultant large defect in the external covering of the abdomen. The patient underwent chemotherapy following cytoreductive surgery. Pathology revealed metastasis of EC, and molecular subtyping showed copy number high of TP53 mutation, implying a poor prognosis.

When EC patients develop giant abdominal wall metastasis, a plastic surgeon should be included before contemplating resection of tumors.

Core Tip: This report presents a rare case of endometrioid adenocarcinoma with extensive abdominal wall metastasis complicated by infection, and highlights the design of the reconstruction of the abdominal wall after resection. A plastic surgeon should be included in the planning before contemplating resection of large tumors.

- Citation: Wang JY, Wang ZQ, Liang SC, Li GX, Shi JL, Wang JL. Plastic surgery for giant metastatic endometrioid adenocarcinoma in the abdominal wall: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(19): 6702-6709

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i19/6702.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6702

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecological malignancy in the United States and its mortality rate is on the rise[1]. The prognosis of patients is relatively good, with an overall five year survival rate of 90.88% for patients staged as IA according to the International Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) 1988 surgical classification[2]. However, the prognosis of patients with advanced disease is extremely poor, with metastasis being the main cause of death[3]. EC commonly metastasizes to the lungs, bones, liver, and brain, but abdominal wall metastasis is extremely rare[4]. Traditionally, local and distant metastatic lesions have been identified using imaging modalities such as pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT). As patients with metastatic EC constitute a heterogeneous group, an individualized approach is required.

Herein, we report a case of endometrioid adenocarcinoma with extensive abdominal wall metastasis complicated by infection. In this case, we highlight the design of the abdominal wall reconstruction after resection.

A 65-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1, was referred to our institution for an identifiable abdominal mass.

Patient’s symptom started about one month ago.

Gynecological history revealed that she underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 11 years ago, and the histopathology revealed a well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma, defined as FIGO stage II. Postoperatively, external beam radiation was prescribed with a total dose of 1000 Gy in 25 fractions. The patient had no evidence of recurrence during the eight-year regular check-ups after her initial therapy until she experienced abdominal pain in the right half of her abdomen in 2018. Subsequently, a right hemicolectomy was performed. This suggested that the colon metastasis was related to her initial gynecological cancer, and histopathology showed moderately differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Molecular subtyping showed a low copy number. The patient received no adjuvant therapy postoperatively.

The patient had no family history.

A mass located on the lower abdomen was found on physical examination, extending down to the mons pubis, up to the laparotomy incision, and outward to the skin surface. The lesion was marked by ruptured vesicles that formed a white crust on the surface (Figure 1A).

Considering that the patient’s body temperature was 37.6℃, further investigations were carried out. The white blood cell count was 11.90 × 109/L and the percentage of neutrophils was as high as 84.3%, but no pathogens were cultured. Taken together, the huge abdominal mass showed signs of infection, and ertapenem-based antibiotics were administered immediately until the hemogram dropped to the normal range.

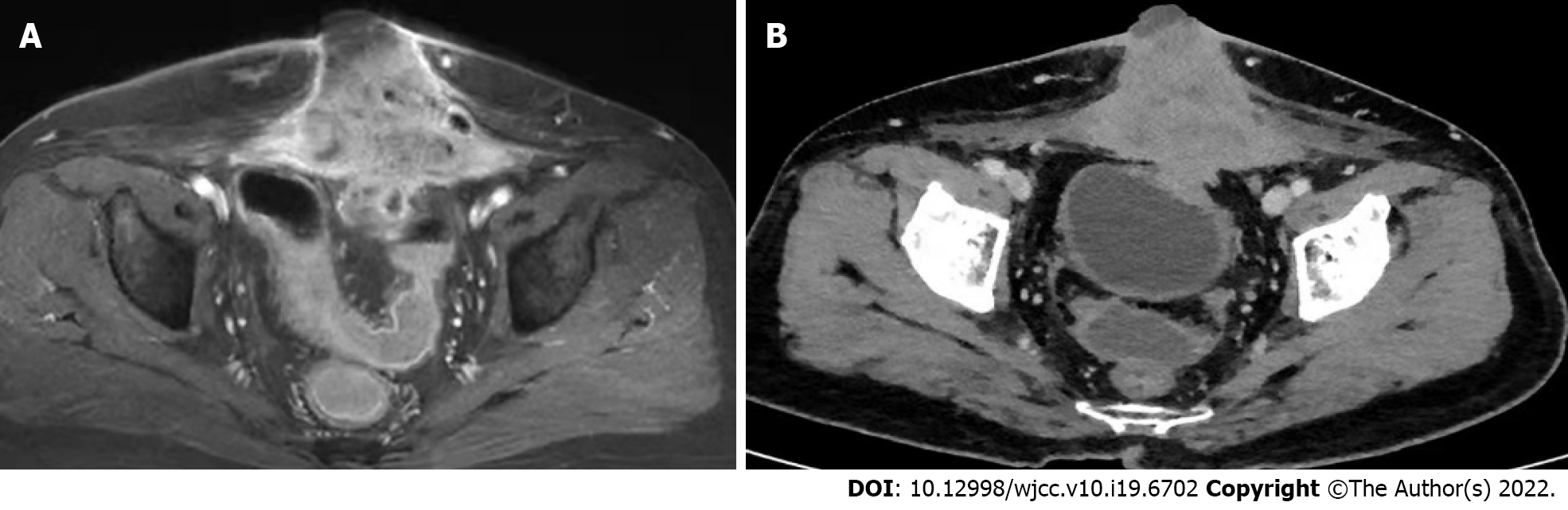

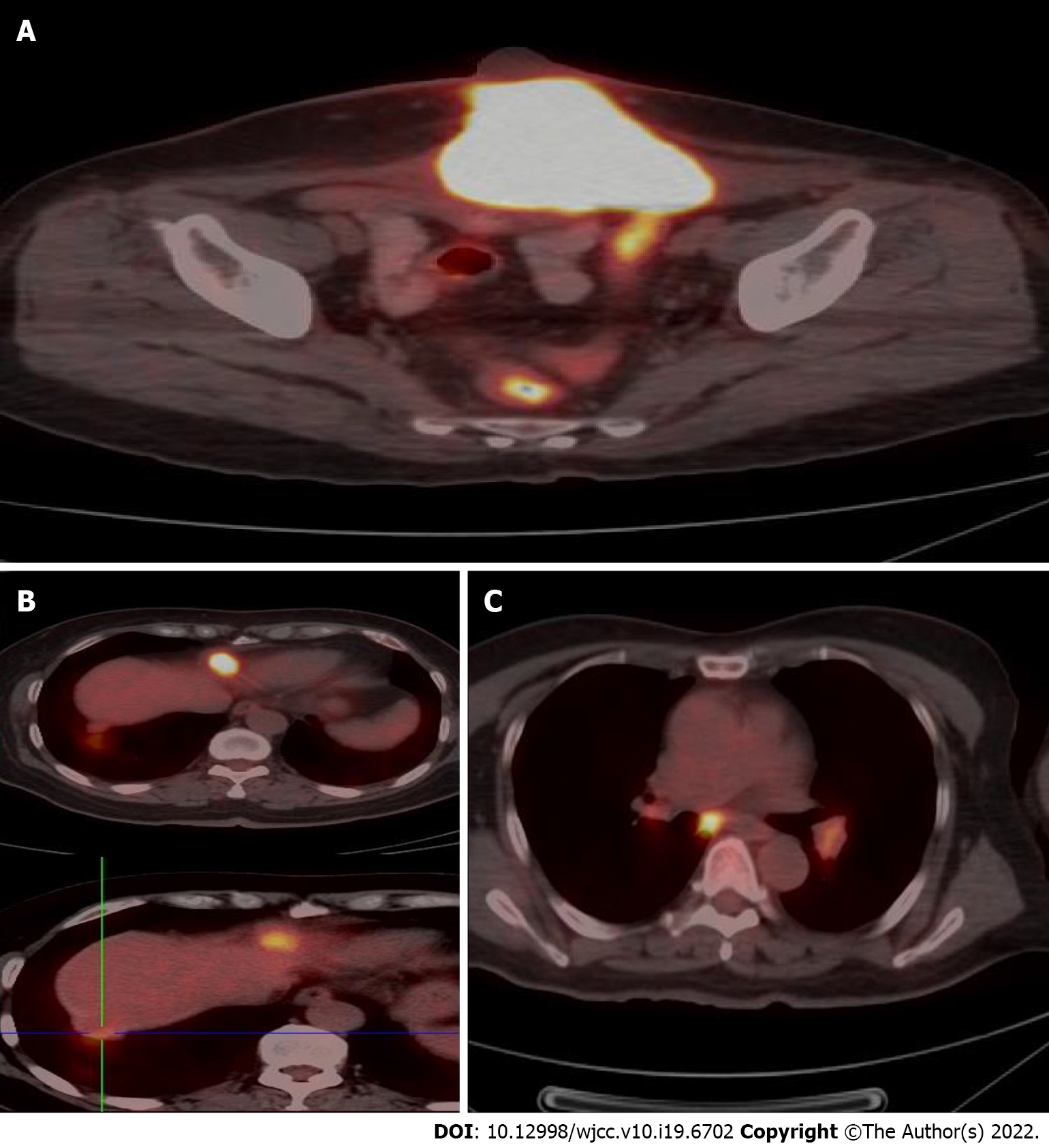

A pelvic MRI was performed which showed an irregular 7.3 cm × 9.9 cm × 6.7 cm mass located on the middle of the anterior abdominal wall, invading the bladder and rectum and infiltrating the rectus abdominis muscle (Figure 2A). The patient then underwent a thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT scan, which also revealed multiple lymph node shadows in the mediastinum, with the largest one approximately 0.8 cm in diameter (Figure 2B). Subsequent PET-CT examination showed increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the mediastinum and hilum, lymph nodes, two nodules under the liver capsule, and a mass on the abdominal wall, with an SUVmax of 3.5-6.0, 10.9, and 3.9, and 21.5 respectively (Figure 3).

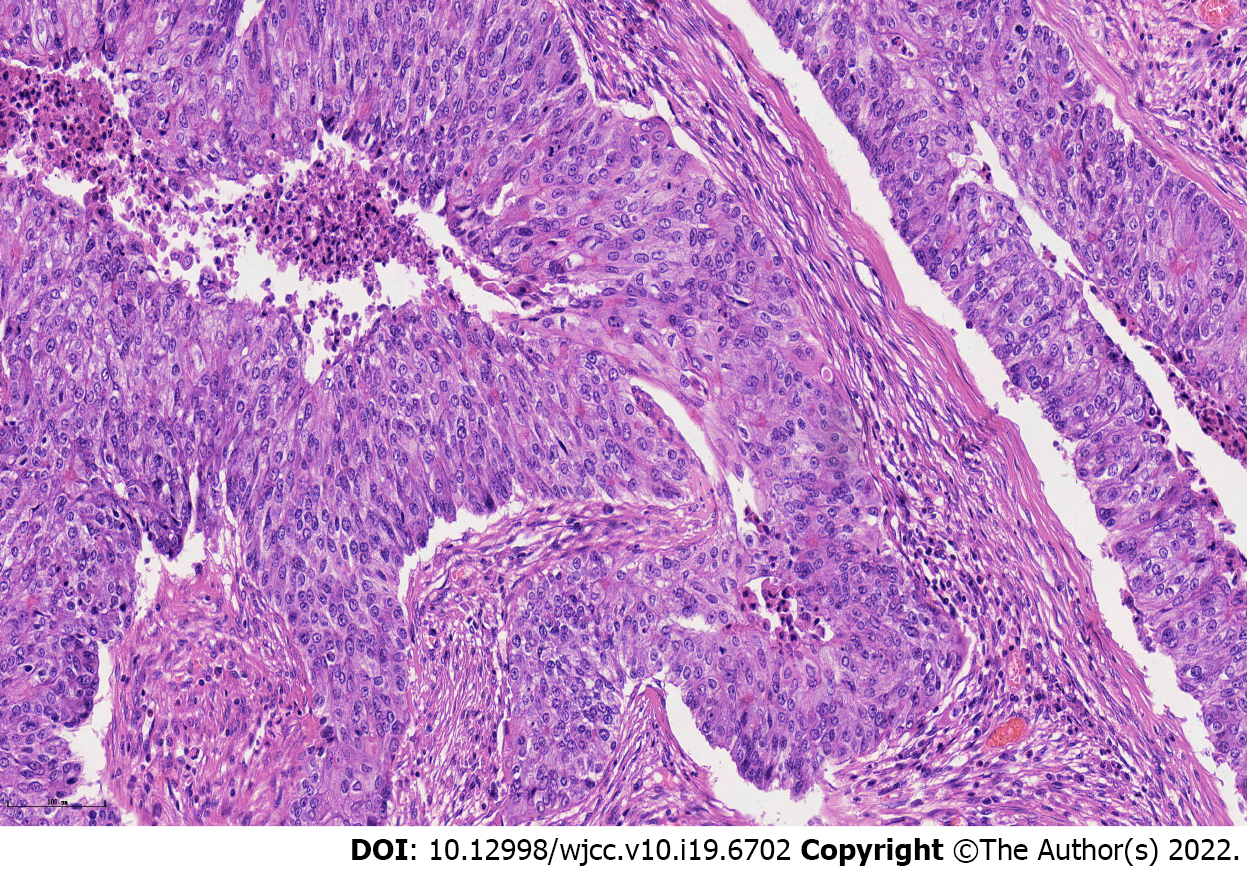

Pathology revealed a metastatic endometrioid adenocarcinoma with poor differentiation, and all surgical margins were tumor-free (Figure 4). Molecular subtyping showed copy number high with TP53 mutation.

When the patient was admitted to our department, we focused on remedies. Chemotherapy was not recommended because of tumor volume, and radiotherapy was not possible because of the infection. Finally, we decided to perform a cytoreductive operation and consulted a plastic surgeon before the surgery to discuss the approach to abdominal wall reconstruction after resection. Exploration of the abdomen and pelvis revealed that the large abdominal mass extended to the top of the bladder and reached the pubic symphysis. Radical resection of the anterior abdominal wall tumor was performed (Figure 1B), and a part of the superior surface of the bladder was removed. No other metastatic lesions were observed. At the end of the operation, the abdominal wall defect appeared as a nearly round hole of 17.0 cm × 15.0 cm, which involved the total abdominal wall thickness, and a Bard composite mesh (20.3 cm × 15.2 cm in size) was used to reconstruct the abdominal wall (Figure 1C). A local flap, measuring 19.0 cm × 17.0 cm, was made to help close the resultant defect of the external covering of the abdomen, measuring 15.0 cm × 13.0 cm (Figure 1D). The wound healed well, and the sutures were removed two weeks after the operation.

The patient began chemotherapy four weeks after surgery with paclitaxel and carboplatin.

The abdominal wall is an unusual location for metastasis of internal malignancies and abdominal metastasis from gastrointestinal or genitourinary malignancies account for only 1%-3% of cases[5]. Therefore, metastatic spread to the abdominal wall is a relatively rare event in early-stage EC. In recent years, with the wide application of laparoscopic technology, increasing port site metastasis has been identified, with an estimated occurrence of 0.18%-0.33% in early-stage EC[6-10].

Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, distant metastasis in any solid tumor is traditionally considered to be related to lymphatic and hematogenous dissemination. Therefore, the anterior abdominal wall, with an abundant arterial supply, anastomotic venous network, and lymphatic system that drains cranially and caudally to several lymphatic chains, including pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes, provides a favorable condition for metastases[11]. Other mechanisms have been postulated, including direct extension and spread through embryonic remnants[5,12]. Moreover, when the metastases are connected to the surgical incision, whether the surgical approach is laparotomy or laparoscopy, one of the potential explanations may be that tumor cells penetrate the uterine wall or the fallopian tube to disseminate intraperitoneally to the recent trauma, and hypothesis is that malignant cells spill through the cervical os during hysterectomy and implant directly in the incision[13]. It has been proposed that when a laparoscopic procedure is performed, high intra-abdominal pressure and implantation at the port site during specimen retrieval may contribute to the dissemination of tumor cells to the abdominal wall. All of these mechanisms may be related to the spread of neoplastic cells to the soft tissue of the abdominal wall; however, in our case, the abdominal wall metastasis of early stage endometrioid adenocarcinoma may be mostly related to local implantation of the free malignant cells shed during the surgery, considering that the patient underwent two laparotomies.

As patients with metastatic EC constitute a heterogeneous group, an individualized approach is required. First, a comprehensive examination is necessary for patients with abdominal wall recurrence to rule out other metastases. An enlarged excision can be performed if there is no distant disease[11]. The surgical procedure consists of an enlarged excision of the tumor and reconstruction of the abdominal wall. Reconstruction poses a great challenge for multidisciplinary cooperation of gynecologists and plastic surgeons[14]. Advances in technology and the plethora of bioprosthetic or engineered tissues have provided more possibilities for doctors and patients[15-17]. A composite mesh is worthy of recommendation because they simplify the surgical treatment of large abdominal wall defects; otherwise, these defects would need further abdominal reconstruction by complex plastic surgery, which may increase morbidity[18]. The nature of the composite mesh makes it prone to providing lasting abdominal support through its safe placement directly onto the bowel, resistance to degradation in vitro and excellent biocompatibility[19,20]. Trauma injuries and tumor resection are the most common causes of large abdominal wall defects[16,21]. Complete resection of abdominal wall lesions is feasible, but preoperative assessment of the defect is the primary consideration for appropriate abdominal reconstruction[22]. Direct closure was performed if the defect was localized. However, it is impossible to advance or rotate the flaps obtained from the area around the defect for construction when the abdominal wall cannot be pulled back to its original position with excessive tension[23]. Therefore, it is highly recommended that a plastic surgeon be consulted before surgery to discuss how to reconstruct the abdominal wall after resection. In addition to covering the defect, the purpose of reconstruction is to prevent visceral eventration and acquire an acceptable cosmetic appearance[24,25]. In our case, the patient underwent extensive full-thickness resection of the abdominal wall tumor, hence, a reconstruction was required. A Bard composite mesh was placed into the abdominal defect area and sutured with 2/0 polypropylene sutures with a sufficient margin. Abdominal reconstruction was then performed by suturing the mesh to the muscular layers of the abdominal wall, and the flaps obtained from the area around the defect were advanced and rotated to achieve soft tissue coverage. Finally, one subcutaneous drain and one pelvic drain were placed.

Surgical resection followed by adjuvant therapy may improve patient survival. However, palliative treatment alone is feasible in some circumstances. Previous studies have shown that radiotherapy for isolated abdominal metastases is associated with high local control rates in EC[26]. Chemotherapy, with paclitaxel combined with carboplatin or cisplatin, may also be frequently used for recurrent EC, especially in cases with unresectable lesions or distant metastases. Hormonal therapy can also be used. A phase II study evaluated the efficacy of everolimus, a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, in combination with letrozole in patients with recurrent EC. The results were encouraging, with a clinical benefit rate of 40% and a confirmed objective response rate of 32%[27]. Data from a recent phase II study evaluating the same combination with metformin showed satisfactory results in patients with recurrent endometrioid endometrial cancer, with a clinical benefit rate of 50% and a confirmed objective response rate of 28%[28]. Considering the large size of the abdominal wall metastasis in our case, surgical resection may have been preferred, followed by chemotherapy.

Additionally, patients with recurrent EC should consider molecular subtyping to guide additional systemic therapy options. It is also recommended for recurrent EC to detect NTRK gene fusions, which are oncogenic drivers of various adult and pediatric tumor types[29]. It has been reported that the application of a first-generation TRK inhibitor, such as larotrectinib or entrectinib, in patients with NTRK fusion-positive cancers achieved satisfactory results with high response rates (> 75%), regardless of tumor histology[30]. Distant metastasis of the abdominal wall in our case was staged as FIGO II; therefore, there may be high-risk factors for molecular subtyping. The results showed copy number high with TP53 mutation and negative NTRK fusion, which may imply a poor prognosis.

When patients with EC develop large abdominal wall metastasis with infection, an individualized approach is proposed. A plastic surgeon should be included in the planning before contemplating resection of large tumors.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fortarezza F, Italy; Hamaguchi S, Japan; Sharma S, India S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Henley SJ, Ward EM, Scott S, Ma J, Anderson RN, Firth AU, Thomas CC, Islami F, Weir HK, Lewis DR, Sherman RL, Wu M, Benard VB, Richardson LC, Jemal A, Cronin K, Kohler BA. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 2020;126:2225-2249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Article Influence: 107.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mahdy H, Casey MJ, Crotzer D. Endometrial Cancer. 2021 Aug 25. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Guo J, Cui X, Zhang X, Qian H, Duan H, Zhang Y. The Clinical Characteristics of Endometrial Cancer With Extraperitoneal Metastasis and the Value of Surgery in Treatment. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2020;19:1533033820945784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ouldamer L, Bendifallah S, Body G, Touboul C, Graesslin O, Raimond E, Collinet P, Coutant C, Bricou A, Lavoué V, Lévêque J, Daraï E, Ballester M; Groupe de Recherche FRANCOGYN. Incidence, patterns and prognosis of first distant recurrence after surgically treated early stage endometrial cancer: Results from the multicentre FRANCOGYN study group. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45:672-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, Borghese M. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nguyen ML, Friedman J, Pradhan TS, Pua TL, Tedjarati SS. Abdominal wall port site metastasis after robotically staged endometrial carcinoma: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:613-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Segarra B, Meyer LA, Malpica A, Bhosale P. Endometrial cancer recurrence at multiple port sites. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020;30:893-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, Eisenkop SM, Schlaerth JB, Mannel RS, Barakat R, Pearl ML, Sharma SK. Recurrence and survival after random assignment to laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:695-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 482] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zivanovic O, Sonoda Y, Diaz JP, Levine DA, Brown CL, Chi DS, Barakat RR, Abu-Rustum NR. The rate of port-site metastases after 2251 laparoscopic procedures in women with underlying malignant disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:431-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Martínez A, Querleu D, Leblanc E, Narducci F, Ferron G. Low incidence of port-site metastases after laparoscopic staging of uterine cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Luz R, Leal R, Simões J, Gonçalves M, Matos I. Isolated abdominal wall metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:505403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Luz R, Leal R, Simões J, Gonçalves M, Matos I. Isolated abdominal wall metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:505403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Macias V, Baiotto B, Pardo J, Muñoz F, Gabriele P. Laparotomy wound recurrence of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:429-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rohrich RJ. The "Current Concepts in Abdominal Wall Reconstruction" Supplement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142:1S-2S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kuwahara H, Salo J, Tukiainen E. Diaphragm reconstruction combined with thoraco-abdominal wall reconstruction after tumor resection. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2018;52:172-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ritz FJT, Poumellec MA, Maertens A, Sebastianelli L, Camuzard O, Balaguer T, Iannelli A. Complex abdominal wall reconstruction after oncologic resection in a sequalae of giant omphalocele: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;81:105707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lak KL, Goldblatt MI. Mesh Selection in Abdominal Wall Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142:99S-106S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kassem MI, El-Haddad HM. Polypropylene-based composite mesh versus standard polypropylene mesh in the reconstruction of complicated large abdominal wall hernias: a prospective randomized study. Hernia. 2016;20:691-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kawaguchi S, Narimoto K, Hamuro A, Nakagawa T, Urata S, Kadomoto S, Iwamoto H, Yaegashi H, Iijima M, Nohara T, Shigehara K, Izumi K, Tachibana D, Kadono Y, Mizokami A, Koyama M. Transvaginal polytetrafluoroethylene mesh surgery for pelvic organ prolapse: 1-year clinical outcomes. Int J Urol. 2021;28:268-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ünek T, Sökmen S, Egeli T, Avkan Oğuz V, Ellidokuz H, Obuz F. The results of expanded-polytetrafluoroethylene mesh repair in difficult abdominal wall defects. Asian J Surg. 2019;42:131-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ünek T, Sökmen S, Egeli T, Avkan Oğuz V, Ellidokuz H, Obuz F. The results of expanded-polytetrafluoroethylene mesh repair in difficult abdominal wall defects. Asian J Surg. 2019;42:131-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pencavel T, Strauss DC, Thomas JM, Hayes AJ. The surgical management of soft tissue tumours arising in the abdominal wall. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:489-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Patel NG, Ratanshi I, Buchel EW. The Best of Abdominal Wall Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:113e-136e. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Boos AM, Beckmann MW, Horch RE, Beier JP. Interdisciplinary Treatment for Cutaneous Abdominal Wall Metastasis from Cervical Cancer with Resection and Reconstruction of the Abdominal Wall Using Free Latissimus Dorsi Muscle Flap: A Case Report. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2014;74:574-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rohrich RJ, Lowe JB, Hackney FL, Bowman JL, Hobar PC. An algorithm for abdominal wall reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:202-16; quiz 217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Grant JD, Garg AK, Gopal R, Soliman PT, Jhingran A, Eifel PJ, Klopp AH. Isolated port-site metastases after minimally invasive hysterectomy for endometrial cancer: outcomes of patients treated with radiotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:869-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Slomovitz BM, Jiang Y, Yates MS, Soliman PT, Johnston T, Nowakowski M, Levenback C, Zhang Q, Ring K, Munsell MF, Gershenson DM, Lu KH, Coleman RL. Phase II study of everolimus and letrozole in patients with recurrent endometrial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:930-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Soliman PT, Westin SN, Iglesias DA, Fellman BM, Yuan Y, Zhang Q, Yates MS, Broaddus RR, Slomovitz BM, Lu KH, Coleman RL. Everolimus, Letrozole, and Metformin in Women with Advanced or Recurrent Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer: A Multi-Center, Single Arm, Phase II Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:581-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Bradley K, Campos SM, Chino J, Chon HS, Chu C, Cohn D, Crispens MA, Damast S, Diver E, Fisher CM, Frederick P, Gaffney DK, George S, Giuntoli R, Han E, Howitt B, Huh WK, Lea J, Mariani A, Mutch D, Nekhlyudov L, Podoll M, Remmenga SW, Reynolds RK, Salani R, Sisodia R, Soliman P, Tanner E, Ueda S, Urban R, Wethington SL, Wyse E, Zanotti K, McMillian NR, Motter AD. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Uterine Neoplasms, Version 3.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:888-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cocco E, Scaltriti M, Drilon A. NTRK fusion-positive cancers and TRK inhibitor therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:731-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 1012] [Article Influence: 168.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |