Published online Jul 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6595

Peer-review started: November 27, 2021

First decision: January 12, 2022

Revised: January 24, 2021

Accepted: May 16, 2022

Article in press: May 16, 2021

Published online: July 6, 2022

Processing time: 209 Days and 5 Hours

Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma (EES) is a member of the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors which is pathologically known as a small, round, blue cell tumor involving bone and soft tissue. The prevalence of EES is only 15%-25% of all Ewing sarcoma and EES often occurs in patients aged from 20-mo-old to 30-years-old resulting in an unfavorable prognosis.

The present case report described a 7-year-old patient with a palpable EES mass of 33 mm × 27 mm × 28 mm in the deep neck with symptoms of persistent dyspnea over the past 5 mo. After laboratory examinations, abnormal physiological and biochemical indicators were not found. Ultrasound images presented the mass to be complex, solid and fluid-filled with circumscribed margins and posterior acoustic enhancement. The mass also presented with partial internal vascularity. The contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging scan illustrated the outstanding enhancement with fast perfusion mode in the early arterial phase.

Our study suggested that a quick-growing mass in the pediatric patient is possibly a malignant tumor whether the mass has well-defined margins or not.

Core Tip: The depth, growth rate and solitary location are valuable indicators for the pre-operative diagnosis of Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma (EES). Meanwhile, the serpentine-like vascularity was present inside EES, accompanied by the outstanding enhancement with fast perfusion mode in the early arterial phase on the contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Multimodal imaging is helpful for clarifying the tumor stage and follow-up.

- Citation: Chen ZH, Guo HQ, Chen JJ, Zhang Y, Zhao L. Imaging-based diagnosis for extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma in pediatrics: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(19): 6595-6601

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i19/6595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6595

In modern medicine, the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors is composed of Ewing sarcoma, extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma (EES), primitive neuroectodermal tumor and Askin tumor[1,2]. EES is the extraskeletal-originated tumors found in soft tissue with or without the involvement of bone which is mainly located in the trunk and lower limbs[1]. It was firstly reported as a paravertebral soft-tissue mass in a child whose pathological presentation was "round cell"[3]. The prevalence of EES is 15%-20% of all Ewing sarcoma[4]. Although it is a rare disease, 85% of the patients are young people aged from 20-mo-old to 30-years-old and is associated with a genetic translocation of t (11; 22) (q12; q24)[4]. To date, EES is still an uncommon disease with little research and leads to an unfavorable prognosis of low survival and high recurrence. Moreover, difficulties remain in the pre-operative diagnosis of EES, even when pathological confirmation has been made[5].

A 7-year-old girl with a palpable mass in the right neck and symptoms of persistent dyspnea for the past 5 mo.

The patient had no fever, headache, trauma or skin redness. Her only symptoms were periodic episodes of dyspnea and nocturnal obstruction.

The patient has a history of bronchitis which was diagnosed in the local outpatient setting. The subsequent symptomatic treatment of bronchitis was almost ineffectual. The patient had no history of diabetes, heart disease, alcohol consumption or smoking.

The patient and family denied that they have histories of cancer, contagion or genetic disease.

The physical examination showed no abnormalities.

The physiological and biochemical values obtained from laboratory tests were normal.

She was preliminarily examined by laryngoscopy, sonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). For the protection of the thyroid, the patient was not subjected to X-ray and Computer tomography (CT) scans.

The greyscale and Doppler imaging were performed by a conventional ultrasound machine equipped with an L12-5 Linear array transducer (Philips healthcare, Bothell, WA, the United States, with L12-5 Linear array transducer) in the initial evaluation. According to the longitudinal section and transection of greyscale images, the soft-tissue mass was measured to be 33 mm × 27 mm × 28 mm, which was located above the right thyroid and inner side of the carotid (Figure 1A and B). It was found that the soft-tissue mass consisted of both hypoechoic solid-component and anechoic fluid, and it appeared as an alveolate mass with circumscribed margins and posterior acoustic enhancement. The Doppler images also suggested that some internal vascularity was present in the soft-tissue mass whereas vascular calcification was not detectable (Figure 1C).

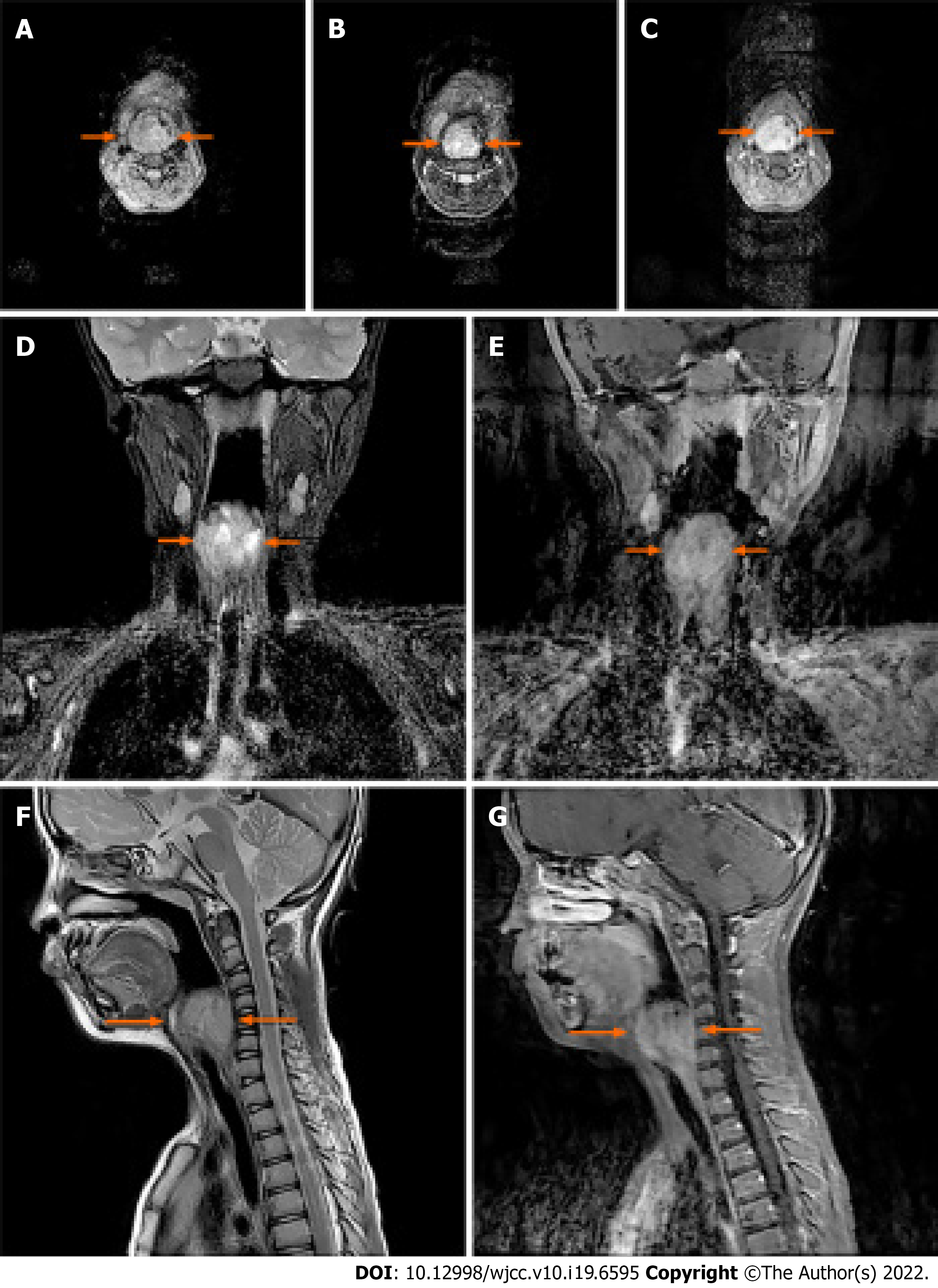

The well-defined mass measured 35 mm × 33 mm leading to an airway stenosis and was demonstrated in the right laryngeal and piriform recess by 3.0T MRI (Discovery MR 750; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, the United States) afterward, which was heterogeneous equisignal, like that in skeletal muscle, on T1 -weighted images (Figure 2A), and high signal intensity on T2 -weighted images (Figure 2B, 2D, and 2F). The contrast-enhanced MRI (gadolinium diethylenetriamine pentetic acid, Magnevist, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) illustrated the outstanding enhancement with fast perfusion mode in the early arterial phase (Figure 2C, 2E, and 2G). Meanwhile, several lymph nodes nearby were revealed as well.

The diagnosis was Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma.

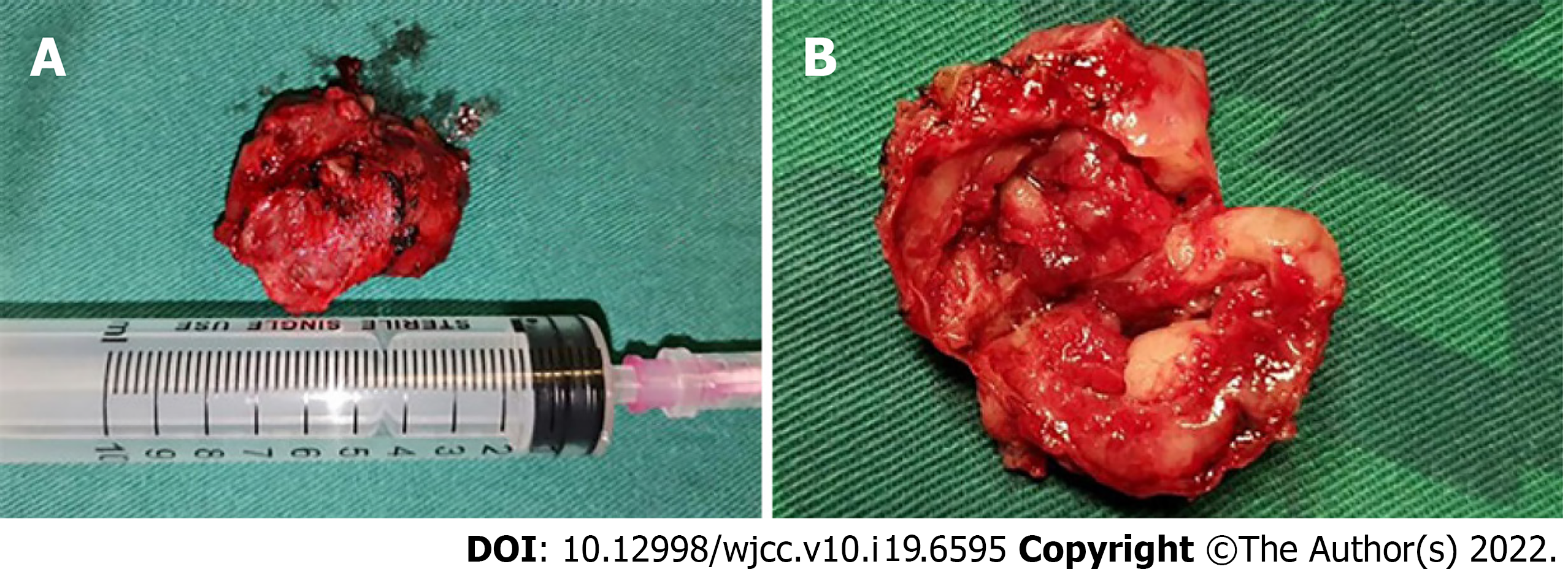

The patient was subjected to the resection of the soft-tissue mass and airway remodeling. It was observed that the dark red mass tissue obtained from the patient was absolutely enveloped in the well-defined capsule showing a pliable but stiff tactile impression (Figure 3A and B), which was quite similar to the characteristics of neurilemmoma.

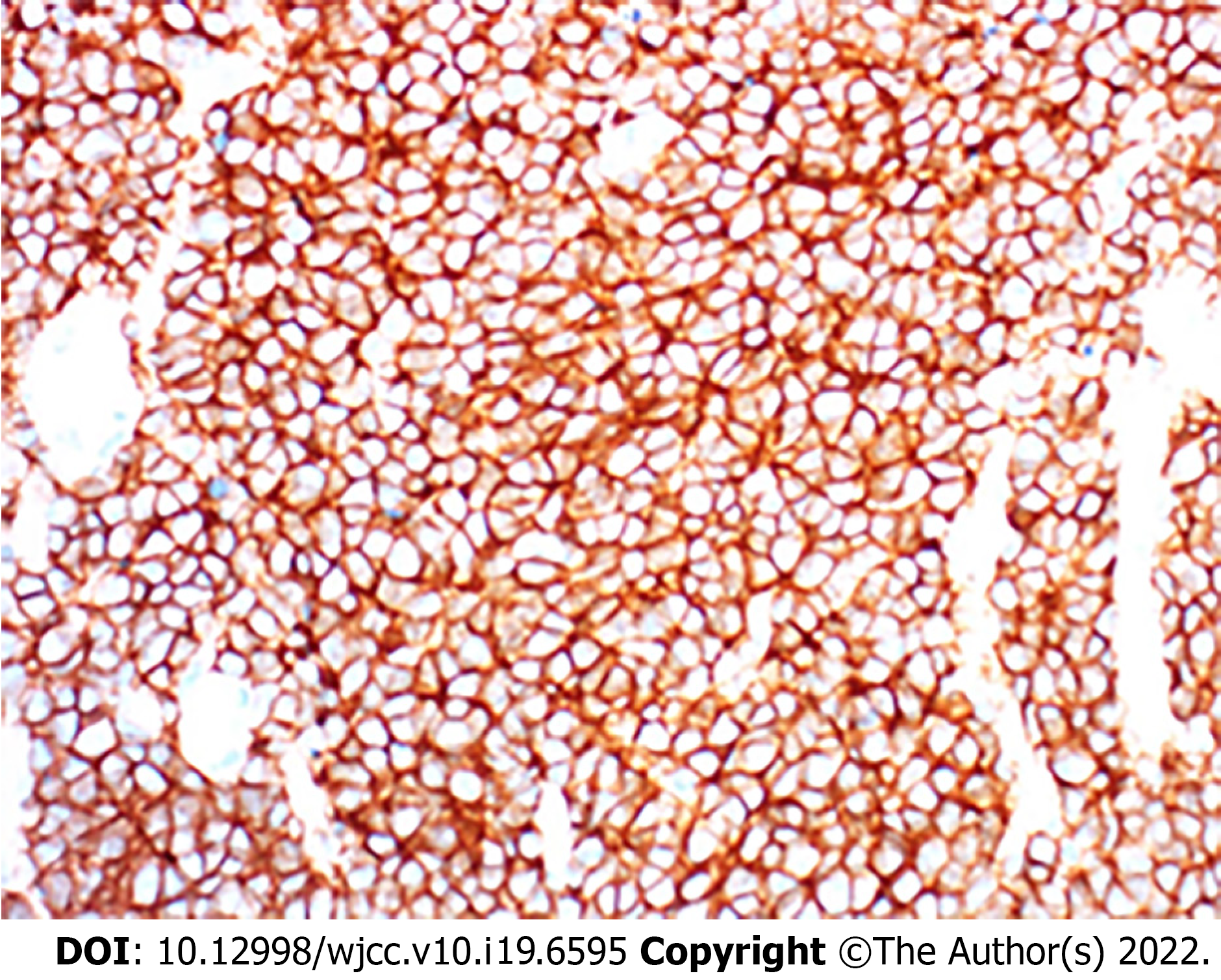

The mass tissue was diagnosed as Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma according to the pathological exami

According to the pre-operative sonography, the lesion presented to be a complex cystic and solid tumor that was enveloped within a well-defined capsule and was located in the deep neck. Meanwhile, the serpentine-like vascularity was found to be present inside the soft-tissue mass, accompanied by the outstanding enhancement with fast perfusion mode in the early arterial phase on the contrast-enhanced MRI. The soft-tissue mass might be misdiagnosed as the following diseases. The first one is dysplastic diseases, such as thyroglossal duct cyst, branchial cleft cyst and cystic lymphangioma. Although dys

The depth, growth rate and solitary location are important and valuable indicators for identifying whether a lesion is an EES lesion or not[6]. Previous studies have indicated that EES are commonly located in the paravertebral region (approximately 32%), lower extremities (approximately 26%), chest wall (approximately 18%), retroperitoneum, pelvis and hip (approximately 11%) and upper extremities (approximately 3%)[6-10]. Hypoechoic mass with or without anechoic areas was frequently reported on sonography[11], in which the increased internal blood flow maybe closely associated with Doppler images. In the case of CT diagnosis, the imaging characteristics of EES was quite similar (similarity approximately 87%) to the muscle[11], and therefore leaving mass effect as seldom an indicator on the image. The same problem was also present in the diagnosis of an EES lesion by MRI. Similar to skeletal muscle, 91% of EES patients show heterogeneous signal intensity on T1-weighted images and almost 100% of patients show a high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. In the case of an MRI diagnosis, the observation of serpentine high-flow vascularity was commonly considered to be the characteristic sign of EES while sometimes it also could be observed in hemangioendothelioma and other vascular lesions[8]. The best indicator, a direct invasion of bone usually happens in the terminal stage, is that MRI can help in clinical staging and follow-up for EES recurrence[12]. Despite the benign-like appearance, sometimes nonspecific imaging features of large, deep in soft-tissue and well-defined may aid the EES diagnosis[6,8,13,14].

In general, surgical resection is well accepted as a first-line therapy for EES patients[15-18]. After resection, some patients should be managed with radiation therapy (RT) or chemotherapy as neoadjuvant therapy for prolonging survival rate[17,18]. With the development of modern medicine, the early diagnosis by multiple imaging technique as well as complete resection could largely improve the prognosis of EES[19]. It was reported that the overall survival (OS) rates of EES patients in 5 years increased from 28% to 61% between 1970 and 1999, and the 5-year OS reaches to above 70% by now[17,20,21], despite the recurrence rate of EES is still quite high[17]. A previous study with 42 EES cases has indicated that the unfavorable prognosis of EES is closely associated with the pelvic tumors, incomplete resections and the presence of metastatic lesions[20]. This study also demonstrated that EES patients could largely benefit from a wide surgical resection with negative microscopic margins and adjuvant local RT. Another study has suggested that the patients’ age below 16 yo and wide surgical resection with negative margins are independent indicators for the prognosis of EES, whereas no statistical significance could be found in tumor size, location, stage, and doses of RT[21].

In summary, the depth, growth rate and solitary location are valuable indicators for the pre-operative diagnosis of EES. The masses with well-defined margins in young patients also has the possibility of being malignant tumors. Multimodal imaging is helpful for determining the tumor stages and follow-up. In addition, more investigations should be carried out for young EES patients with a poor prognosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bhardwaj R, India; Naganuma H, Japan A-Editor: Lin FY S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Murphey MD, Senchak LT, Mambalam PK, Logie CI, Klassen-Fischer MK, Kransdorf MJ. From the radiologic pathology archives: ewing sarcoma family of tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2013;33:803-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Durer S, Shaikh H. Ewing Sarcoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2021, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2021. |

| 3. | Tefft M, Vawter GF, Mitus A. Paravertebral "round cell" tumors in children. Radiology. 1969;92:1501-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Javery O, Krajewski K, O'Regan K, Kis B, Giardino A, Jagannathan J, Ramaiya NH. A to Z of extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma family of tumors in adults: imaging features of primary disease, metastatic patterns, and treatment responses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W1015-W1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cheng Y, Yang L, Zhang N, Chen GS, Li J, Liu YF, Zhou CJ. Extraskeletal Ewing's Sarcoma with CD7 Positivity and T-cell Receptor/Immunoglobulin Rearrangement Masquerading as T-lymphoblastic Lymphoma. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2020:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Angervall L, Enzinger FM. Extraskeletal neoplasm resembling Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;36:240-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Soule EH, Newton W Jr, Moon TE, Tefft M. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma: a preliminary review of 26 cases encountered in the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. Cancer. 1978;42:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kennedy JG, Eustace S, Caulfield R, Fennelly DJ, Hurson B, O'Rourke KS. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1996-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rose JS, Hermann G, Mendelson DS, Ambinder EP. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma with computed tomography correlation. Skeletal Radiol. 1983;9:234-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Harimaya K, Oda Y, Matsuda S, Tanaka K, Chuman H, Iwamoto Y. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor and extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma arising primarily around the spinal column: report of four cases and a review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:E408-E412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | O'Keeffe F, Lorigan JG, Wallace S. Radiological features of extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma. Br J Radiol. 1990;63:456-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hopp AC, Nguyen BD. Gastrointestinal: Multi-modality imaging of extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma of the stomach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Spaulding SL, Xing MH, Seo GT, Matloob A, Khorsandi AS, Urken ML. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma of the buccal space. Clin Imaging. 2021;73:108-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gazula S, Rani VL, Jonathan GT, Kumar NN. Extraskeletal Ewing's Sarcoma Masquerading as Infantile Benign Neck Mass. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2019;24:209-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mangual D, Bisbal-Matos LA, Jiménez-Lee R, Vélez R, Noy M. Extraskeletal presentation of Ewing's Sarcoma. P R Health Sci J. 2018;37:55-57. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Cantu C, Bressler E, Dermawan J, Paral K. Extraskeletal Ewing Sarcoma of the Jejunum: A Case Report. Perm J. 2019;23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Salah S, Abuhijla F, Ismail T, Yaser S, Sultan I, Halalsheh H, Shehadeh A, Abdelal S, Almousa A, Jaber O, Abu-Hijlih R. Outcomes of extraskeletal vs. skeletal Ewing sarcoma patients treated with standard chemotherapy protocol. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22:878-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gulsen S, Vicdan H. Primary Extraskeletal Ewing Sarcoma of the Parotid Gland. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;100:147-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ottóffy G, Komáromy H. Extraskeletal, intradural, non-metastatic Ewing's sarcoma. Case report. Ideggyogy Sz. 2020;73:286-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rud NP, Reiman HM, Pritchard DJ, Frassica FJ, Smithson WA. Extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma. A study of 42 cases. Cancer. 1989;64:1548-1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |