Published online Jun 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5495

Peer-review started: December 21, 2021

First decision: January 25, 2022

Revised: January 30, 2022

Accepted: April 29, 2022

Article in press: April 29, 2022

Published online: June 6, 2022

Processing time: 162 Days and 19.6 Hours

Congenital tuberculosis (TB), tuberculous meningitis, and situs inversus totalis are rare diseases. We here report a patient who simultaneously suffered from these three rare diseases. There is currently no such report in the literature. Congenital TB is easily misdiagnosed and has a high case fatality rate. Timely anti-TB treatment is required.

A 19-day-old male newborn was admitted to hospital due to a fever for 6 h. His blood tests and chest X-rays suggested infection, and he was initially considered to have neonatal pneumonia and sepsis. He did not respond to conventional anti-infective treatment. Finally, Mycobacterium tuberculosis was found in sputum lavage fluid on the 10th day after admission. In addition, the mother's tuberculin skin test was positive, with an induration of 22 mm, and her pelvic computed tomography scan suggested the possibility of tuberculous pelvic inflammatory disease. The child was diagnosed with congenital TB and immediately managed with anti-TB therapy and symptomatic supportive treatment. However, the infant's condition gradually worsened and he developed severe tuberculous pneumonia and tuberculous meningitis, and eventually died of respiratory failure.

If conventional anti-infective treatment is ineffective in neonatal pneumonia, anti-TB treatment should be considered.

Core Tip: Congenital tuberculosis (TB) is rare in the clinic, and early diagnosis is challenging. The disease develops rapidly, and the mortality rate is exceptionally high. In the present case, the infant's condition worsened due to delays in diagnosis and anti-TB treatment, and he developed severe tuberculous pneumonia and tuberculous meningitis, and eventually died of respiratory failure. Early screening of TB infection and anti-TB treatment are essential to reduce mortality and improve the prognosis in children who do not respond to conventional anti-infective therapy.

- Citation: Lin H, Teng S, Wang Z, Liu QY. Congenital tuberculosis with tuberculous meningitis and situs inversus totalis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(16): 5495-5501

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i16/5495.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5495

Congenital tuberculosis (TB) refers to an infection due to contact between the baby and the TB bacillus in the uterus or during delivery. Maternal TB can be transmitted to the fetus through the placenta or by inhalation of infected amniotic fluid. The former forms primary complexes in the liver of infants, and the latter forms primary lesions in the lungs or gastrointestinal tract[1]. Congenital TB is very rare, and the mortality rate is exceptionally high[2,3]. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death[2,4,5]. Intracranial infection is one of the most severe complications, seriously affecting the prognosis[3]. Misdiagnosis and untimely treatment are the main reasons for aggravation of the condition. Situs inversus totalis (SIT) is a rare congenital malformation, and some patients may also suffer from defective ciliary motility[6]. The ciliary immobility is involved in the absence of mucociliary transport in the respiratory epithelia[7], which may induce lung infections. We here report a patient who suffered from rare congenital TB, tuberculous meningitis, and SIT. Congenital TB complicated with SIT was not found from the Google Scholar and PubMed databases.

A 19-day-old male newborn was admitted to the hospital with a fever for 6 h.

The child was born at 41 wk of gestation and was delivered smoothly. The birth weight was 2.925 kg. His respiratory rate was 50 breaths/min, weight was 3.93 kg, heart rate was 150 beats/min, and he had no intrauterine distress and no premature rupture of fetal membranes. Fever occurred 6 h before admission, and the highest body temperature was 38.2 ℃.

The baby was delivered normally without a history of allergies.

The patient’s mother had a history of miscarriage. Both parents denied a history of TB, but his grandmother had TB when she was young.

Breath sounds were rough in both lungs, with an increased breathing rate and wet rales could be heard.

The following parameters were observed in serum: C-reactive protein 46.3 mg/L (reference range: ≤ 6.0 mg/L), procalcitonin 1.23 μg/L (reference range: < 0.054 μg/L), white blood cells (WBC) 22.92 × 109/L (reference range: 15-20 × 109/L), neutrophils 0.701, total bilirubin 87.9 μmol/L (reference range: < 26.0 μmol/L), and indirect bilirubin 81.2 μmol/L (reference range: < 14.0 μmol/L). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was cloudy, with a chloride ion level of 117.5 mmol/L (reference range: 120.0-132.0 mmol/L), protein concentration 0.92 g/L (reference range: 0.08-0.43 g/L), glucose 3.15 mmol/L (reference range: 3.9-5.0 mmol/L), adenosine deaminase 0.2 U/L, and WBC 35 × 106/L (reference range: < 30 × 106/L). Bacterial testing showed Gram-positive cocci on smears, acid-fast bacilli were found on acid-fast staining, and the tuberculin-γ-interferon release test was positive. Microbial genetic testing detected the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

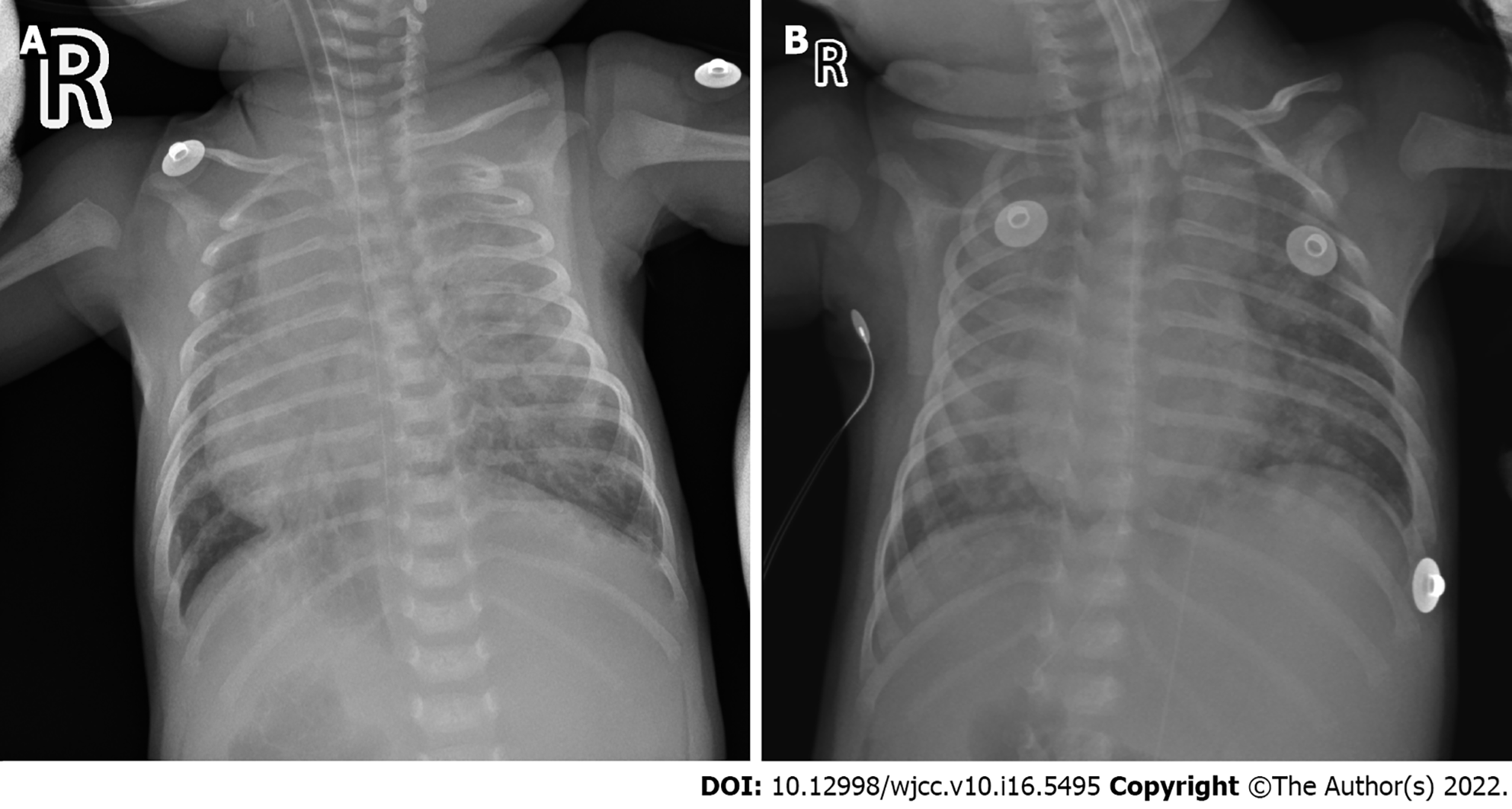

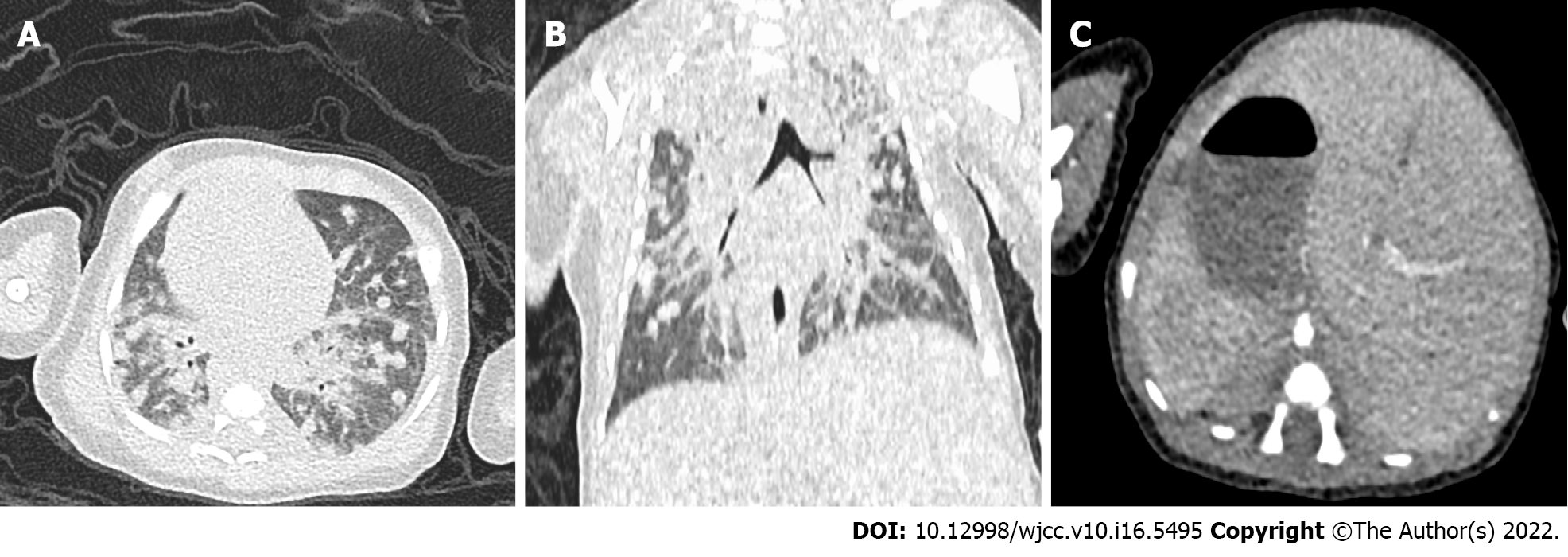

Chest radiography showed increased texture and thickening of the lungs, scattered with patchy high-density shadows. In addition, the apex of the heart and gastric bobble was on the right, and the liver was on the left (Figure 1). Chest computed tomography (CT) showed multiple nodules in both lungs, and hilar lymph nodes were enlarged (Figure 2A and B). The heart, liver, and spleen were also completely reversed, showing mirror-like changes (Figure 2B and C).

The baby was finally diagnosed with congenital TB with tuberculous meningitis and SIT.

Following admission, the patient underwent repeated tests for viruses and bacteria, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other pathogens. The test samples included blood, sputum, gastric juice, and CSF. The test results in the first 10 d were all negative. Amoxicillin and clavulanate potassium were given on the day of admission. Potassium retinoic acid (0.117 g IV q8h) was discontinued the next day and changed to oseltamivir phosphate granules (10 mg oral qd) and ceftazidime (0.19 g IV q8h). Vancomycin (58 mg IV q8h) was administered and the blood concentration of vancomycin was controlled at 7.4 μg/mL (effective range: 7-10 μg/mL). Meropenem (0.15 g IV q8h) was added on the 4th day after admission. However, these anti-infective treatments were ineffective, lung exudation was aggravated, and regular blood oxygen saturation could not be maintained. Invasive ventilation was then used to support the patient's breathing. Neurological symptoms such as epilepsy and irritability were also observed. On the 10th day after admission, acid-fast bacilli were found in the patient's sputum following acid-fast staining. Microbial genetic tests confirmed Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Vancomycin, oseltamivir phosphate particles, and ceftazidime were then stopped, and anti-TB treatment was started with niacin injection (0.057 g IV qd), pyrazinamide tablets (0.13 g gastric tube injection qd), and rifampicin injection (0.057 g IV qd). After 7 d of anti-TB treatment, the patient's chest radiography showed improvement in lung exudation (Figure 1). The child was kept alive through invasive ventilation, but eventually died of respiratory failure due to the worsening of the disease.

The newborn underwent anti-TB treatment, but due to delays in diagnosis and treatment, his condition continued to deteriorate and he eventually developed severe pneumonia and tuberculous meningitis, and died of respiratory failure at 38 d.

Congenital TB is a rare disease. In 2005, fewer than 376 cases were reported worldwide[2]. Cantwell et al[1] proposed the classic diagnostic criteria for congenital TB, where infants were confirmed to have TB if they had at least one of the followings: Symptoms in the first week after birth, primary liver TB complex, maternal genital tract or placental TB, and postpartum transmission ruled out by thorough investigation of contacts. In this case, the mother's tuberculin skin test was positive, and pelvic CT suggested possible tuberculous peritonitis. Moreover, Mycobacterium tuberculosis was found in the baby's sputum, and chest radiography indicated progressive and disseminated TB. Therefore, our case met these diagnostic criteria.

The clinical manifestations of congenital TB are non-specific, making early diagnosis difficult[1,5]. The most common clinical symptoms are loss of appetite, fever, restlessness, hypoplasia, weight loss, cough, respiratory distress, hepatosplenomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and abdominal distension[2,8]. Generally, congenital TB is easily misdiagnosed as pneumonia, sepsis, and purulent meningitis[3]. Conventional antibiotic treatment is ineffective and the disease may progress to serious complications such as miliary TB and tuberculous meningitis. These serious complications may be related to the infant's immature innate immunity[9]. The clinical symptoms of the child, in this case, were mainly fever, loss of appetite, restlessness, and respiratory distress. These symptoms are non-specific. Mycobacterium tuberculosis was not detected in the baby in the first 10 d after admission. The mother had no symptoms of TB infection before and after childbirth. Therefore, TB infection could not be diagnosed early.

Laboratory tests for congenital TB are generally non-characteristic and easily confused with acute infections due to other pathogens[10]. The most common reaction is an increase in the number of WBC and inflammatory indicators. Identifying the presence of tubercle bacilli by fluid body cultures, acid-fast staining, or tissue biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of TB[11]. In our case, bacteria and viruses were tested immediately after admission, and the results were negative. In addition, repeated acid-fast staining of sputum and gastric juice was negative, and tubercle bacilli were not found in the sputum until the 10th day after admission. Delayed diagnosis is a crucial cause of disease aggravation.

The imaging manifestations of congenital TB have specific characteristics. Early imaging of lesions may include interstitial pneumonia[12], and miliary pneumonia and multiple pulmonary nodules may appear when the condition worsens. Multiple pulmonary nodules are considered disease progression[12]. Peng et al[3] suggested that miliary TB on chest imaging 4 wk postpartum should be used as one of the diagnostic criteria for congenital TB, which can provide a timely basis for diagnosis and treatment. If Mycobacterium tuberculosis spreads to the liver and spleen via the blood, it can form a primary complex. Abdominal CT showed hepatosplenomegaly, and multiple low-density primary complexes were also seen. In our case, the baby's chest radiography and chest CT showed scattered high-density nodules in both lungs, thickened lung texture, enlarged hilar lymph nodes, and normal size and density of the liver and spleen. In addition, the dextrocardia and internal organs were reversed (Figures 1 and 2). Therefore, we believe that the cause in this case was the infant inhaling or ingesting amniotic fluid contaminated by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

In recent decades, neonatal tuberculous meningitis has rarely been reported[13-15]. Common neurological symptoms and signs include drowsiness, meningeal irritation, cranial nerve palsy, epilepsy, hemiplegia, alteration of consciousness, coma, etc[16]. About half of all tuberculous meningitis infections cause severe disability or death[17]. When TB meningitis is suspected, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be selected, as it is unique in assessing early and late disease and is effective in children with suspected TB meningitis[18,19]. In this case, the infant's neurological symptoms were irritability, convulsions, and poor response. The number of WBCs and protein concentrations in the CSF were increased, and the concentrations of glucose and chloride ions were decreased. Combined with the detection of TB and multiple pulmonary nodules following sputum analysis, this was consistent with the diagnostic criteria for tuberculous meningitis[20]. Unfortunately, head MRI was not performed at that time.

Inborn anomalies of organ placement are rare developmental abnormalities with an incidence of about 1/8000[21], which can be divided into SIT and incomplete situs inversus[22]. However, in 20%-25% of SIT cases, they also have Kartagener syndrome (KS) (bronchial immobility, bronchiectasis, chronic sinusitis, and male infertility)[23,24]. KS is also known as ciliary immobility syndrome, which can lead to obstruction of mucus drainage from the respiratory tract, which increases the possibility of lung infection. However, we cannot confirm whether the baby has KS and whether KS will increase the prevalence of congenital TB.

The mortality rate of congenital TB is very high, close to 50%, usually due to delayed diagnosis and treatment[5]. The clinical manifestations do not improve after antibiotic treatment, and the condition of 96% of children may worsen[3]. Early diagnosis and timely anti-TB treatment can significantly reduce infant mortality and improve prognosis[3]. Newborns with congenital TB should receive isoniazid (10-15 mg/kg/d), rifampicin (10-20 mg/kg/d), pyrazinamide (20-40 mg/kg/d), and streptomycin (20-40 mg/kg/d) intravenously for 2 mo; isoniazid and rifampicin should be continued for 6 mo[25]. Our patient only started anti-TB treatment on the 10th day after admission, but his condition continued to deteriorate, and he eventually developed severe pneumonia and tuberculous meningitis and died of respiratory failure at 38 d.

Congenital TB is very rare, and concurrent tuberculous meningitis and congenital SIT have not been reported. It is not clear whether they are related or not. The clinical manifestations of congenital TB are non-specific, the detection of pathogenic bacteria is difficult, it is easily misdiagnosed, the fatality rate of the disease is high, and it can progress to severe tuberculous meningitis. Early diagnosis and anti-TB treatment are the keys to reducing mortality and improving infant prognosis. For infants with a high suspicion of TB infection, empirical anti-TB treatment should be administered.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Akbulut S, Turkey; Novita BD, Indonesia S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Cantwell MF, Shehab ZM, Costello AM, Sands L, Green WF, Ewing EP Jr, Valway SE, Onorato IM. Brief report: congenital tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1051-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Li C, Liu L, Tao Y. Diagnosis and treatment of congenital tuberculosis: a systematic review of 92 cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14:131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Peng W, Yang J, Liu E. Analysis of 170 cases of congenital TB reported in the literature between 1946 and 2009. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:1215-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abughali N, Van der Kuyp F, Annable W, Kumar ML. Congenital tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:738-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abalain ML, Petsaris O, Héry-Arnaud G, Marcorelles P, Couturaud F, Dobrzynski M, Payan C, Gutierrez C. Fatal congenital tuberculosis due to a Beijing strain in a premature neonate. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:733-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Douard R, Feldman A, Bargy F, Loric S, Delmas V. Anomalies of lateralization in man: a case of total situs inversus. Surg Radiol Anat. 2000;22:293-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Afzelius BA. A human syndrome caused by immotile cilia. Science. 1976;193:317-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 900] [Cited by in RCA: 822] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 8. | Mittal H, Das S, Faridi MM. Management of newborn infant born to mother suffering from tuberculosis: current recommendations & gaps in knowledge. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:32-39. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Whittaker E, Kampmann B. Perinatal tuberculosis: new challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in infants and the newborn. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84:795-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schwander SK, Torres M, Carranza C C, Escobedo D, Tary-Lehmann M, Anderson P, Toossi Z, Ellner JJ, Rich EA, Sada E. Pulmonary mononuclear cell responses to antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in healthy household contacts of patients with active tuberculosis and healthy controls from the community. J Immunol. 2000;165:1479-1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Diar H, Velaphi S. Congenital tuberculosis as a proxy to maternal tuberculosis: a case report. J Perinatol. 2009;29:709-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Neyaz Z, Gadodia A, Gamanagatti S, Sarthi M. Imaging findings of congenital tuberculosis in three infants. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:e42-e46. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Waecker NJ Jr, Connor JD. Central nervous system tuberculosis in children: a review of 30 cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:539-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Leung AN, Müller NL, Pineda PR, FitzGerald JM. Primary tuberculosis in childhood: radiographic manifestations. Radiology. 1992;182:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tung YR, Lai MC, Lui CC, Tsai KL, Huang LT, Chang YC, Huang SC, Yang SN, Hung PL. Tuberculous meningitis in infancy. Pediatr Neurol. 2002;27:262-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Thwaites GE, van Toorn R, Schoeman J. Tuberculous meningitis: more questions, still too few answers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:999-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Thwaites GE, Macmullen-Price J, Tran TH, Pham PM, Nguyen TD, Simmons CP, White NJ, Summers D, Farrar JJ. Serial MRI to determine the effect of dexamethasone on the cerebral pathology of tuberculous meningitis: an observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Garg RK, Sinha MK. Tuberculous meningitis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Neurol. 2011;258:3-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Daniel BD, Grace GA, Natrajan M. Tuberculous meningitis in children: Clinical management & outcome. Indian J Med Res. 2019;150:117-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kobus C, Targarona EM, Bendahan GE, Alonso V, Balagué C, Vela S, Garriga J, Trias M. Laparoscopic surgery in situs inversus: a literature review and a report of laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for diverticulitis in situs inversus. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2004;389:396-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Trautner M, Szyszko T, Gnanasegaran G, Nunan T. Interesting image. Situs inversus totalis in newly diagnosed lymphoma: additional value of hybrid imaging. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35:26-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Inoue Y, Suga A, Sekido Y, Yamada S, Iwazaki M. A case of surgically resected lung cancer in a patient with Kartagener's syndrome. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2011;36:21-24. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Shimizu J, Arano Y, Adachi I, Morishita M, Fuwa B, Saitoh M, Minato H. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung in a patient with complete situs inversus. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:178-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Patel S, DeSantis ER. Treatment of congenital tuberculosis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:2027-2031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |