Published online Jun 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5394

Peer-review started: September 10, 2021

First decision: January 10, 2022

Revised: January 19, 2022

Accepted: April 9, 2022

Article in press: April 9, 2022

Published online: June 6, 2022

Processing time: 264 Days and 16.9 Hours

Aortic dissection (AD) and pulmonary embolism (PE) are both life-threatening disorders. Because of their conflicting treatments, treatment becomes difficult when they occur together, and there is no standard treatment protocol.

A 67-year-old man fell down the stairs due to syncope and was brought to our hospital as a confused and irritable patient who was uncooperative during the physical examination. Further examination of the head, chest and abdomen by computed tomography revealed a subdural hemorrhage, multiple rib fractures, a hemopneumothorax and a renal hematoma. He was admitted to the Emergency Intensive Care Unit and given a combination of oxygen therapy, external rib fixation, analgesia and enteral nutrition. The patient regained consciousness after 2 wk but complained of abdominal pain and dyspnea with an arterial partial pressure of oxygen of 8.66 kPa. Computed tomography angiograms confirmed that he had both AD and PE. We subsequently performed only nonsurgical treatment, including nasal high-flow oxygen therapy, nonsteroidal analgesia, amlodipine for blood pressure control, beta-blockers for heart rate control. Eight weeks after admission, the patient improved and was discharged from the hospital.

Patients with AD should be alerted to the possibility of a combined PE, the development of which may be associated with aortic compression. In patients with type B AD combined with low-risk PE, a nonsurgical, nonanticoagulant treatment regimen may be feasible.

Core Tip: Here we show a case of a patient with multiple injuries from a fall who was admitted 2 wk later and found to have a concurrent type B aortic dissection, and low-risk pulmonary embolism. We determined that the thrombosis was probably related to compression of the aortic hematoma. After 6 wk of nasal high-flow oxygen therapy, analgesia, slowing of heart rate, lowering of blood pressure, and non-anticoagulation, the patient was discharged. This case shows us that non-surgical non-anticoagulation may be appropriate for patients with aortic dissection combined with low-risk pulmonary embolism.

- Citation: Chen XG, Shi SY, Ye YY, Wang H, Yao WF, Hu L. Successful treatment of aortic dissection with pulmonary embolism: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(16): 5394-5399

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i16/5394.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5394

Aortic dissection (AD) is a fatal disease that involves an intimal tear of the aortic wall and allows blood to flow within the layers of the vessel. Based on the Stanford classification criteria, AD can manifest in two ways: Type A affects the ascending aorta, whereas type B affects all other aortic segments. While type A: AD cases often demand urgent surgical intervention, the vast majority of type B: AD cases can be treated with conventional methods[1]. Pulmonary embolism (PE), which is caused by a clot in one of the pulmonary arteries and blocks blood flow to the heart and lungs, can also be life-threatening. Nevertheless, these two diseases rarely occur simultaneously in the same patient. If a patient suffers from both life-threatening diseases at the same time, it becomes much more challenging to define treatment options and interventions. In fact, currently, there are no well-recognized guidelines for the treatment of simultaneous AD and PE in the same patient. In this report, we describe the case of a 67-year-old man with both AD type B and acute PE who was successfully treated with nonsurgical methods.

Fall once 6 h ago with disturbance of consciousness.

A 67-year-old man fell down the stairs due to syncope and was brought to our hospital as a confused and irritable patient who was uncooperative during the physical examination.

He has a history of hypertension and thyroidectomy.

The patient had no disease-related personal or family history.

The examination at admission revealed a heart rate of 150 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 28 breaths per minute, SpO2 of 92% and a blood pressure of 138/92 mmHg. After 2 wk, he had a heart rate of 116 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 26 breaths per minute, SpO2 of 88% and a blood pressure at 138/79 mmHg.

The laboratory findings on admission were white blood cell (WBC) at 16.67 × 109/L, hemoglobin at 145 g/L, platelets at 229 × 109/L, APTT at 33.4 s, fibrin degradation products at 265.78 µg/mL, D-dimer at 36.69 µg/mL, blood creatinine at 115 µmol/L and arterial partial pressure of oxygen at 10.2 kpa. After 2 wk, The laboratory findings were WBC at 17.19 × 109/L, hemoglobin at 92 g/L, platelets at 506×109/L, APTT at 30.4 s, fibrin degradation products at 19.98 µg/mL, D-dimer at 3.62 µg/mL, blood creatinine at 57 µmol/L, cTNI at 0.01 ng/mL, and BNP at 73 pg/mL.

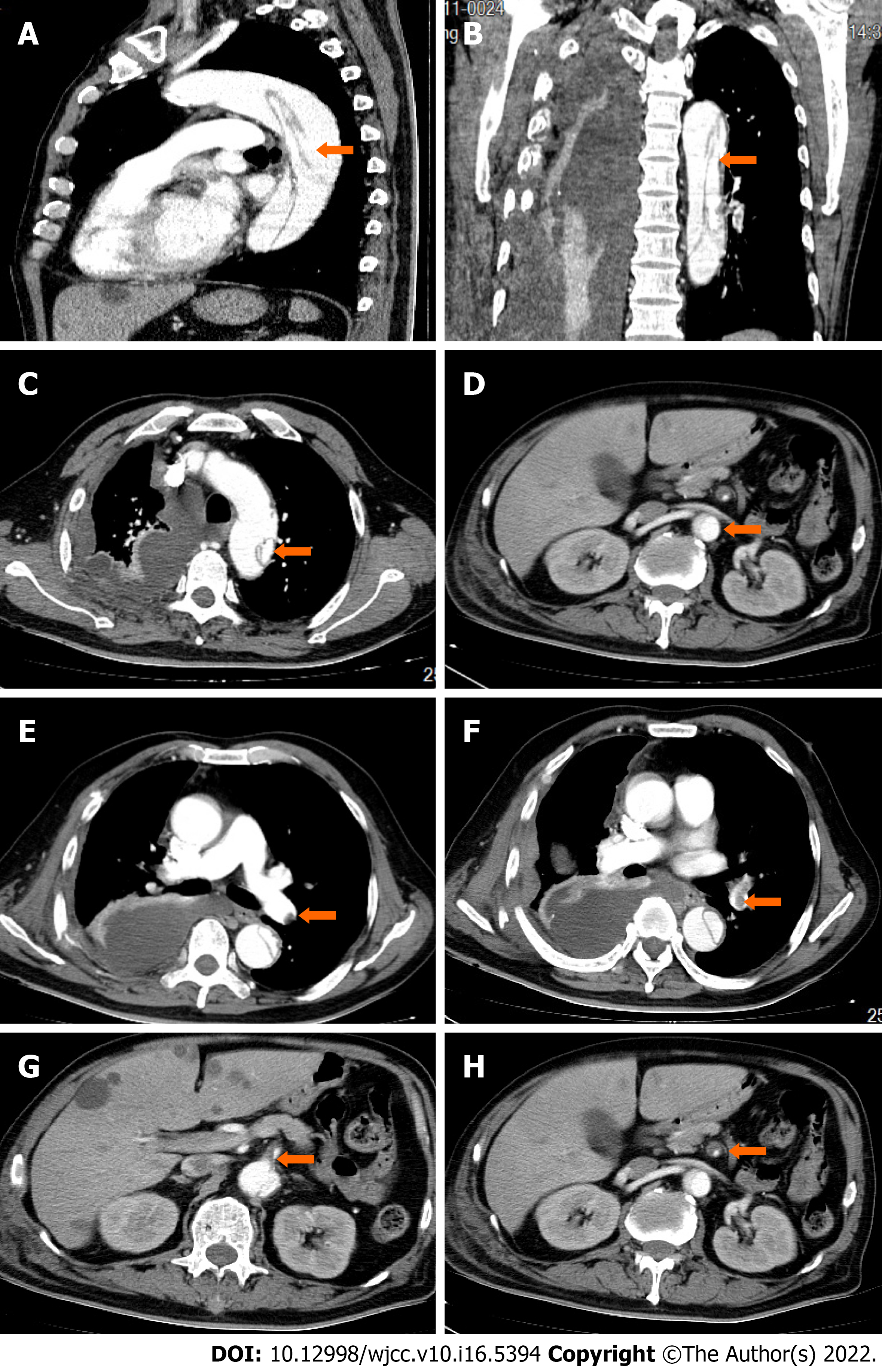

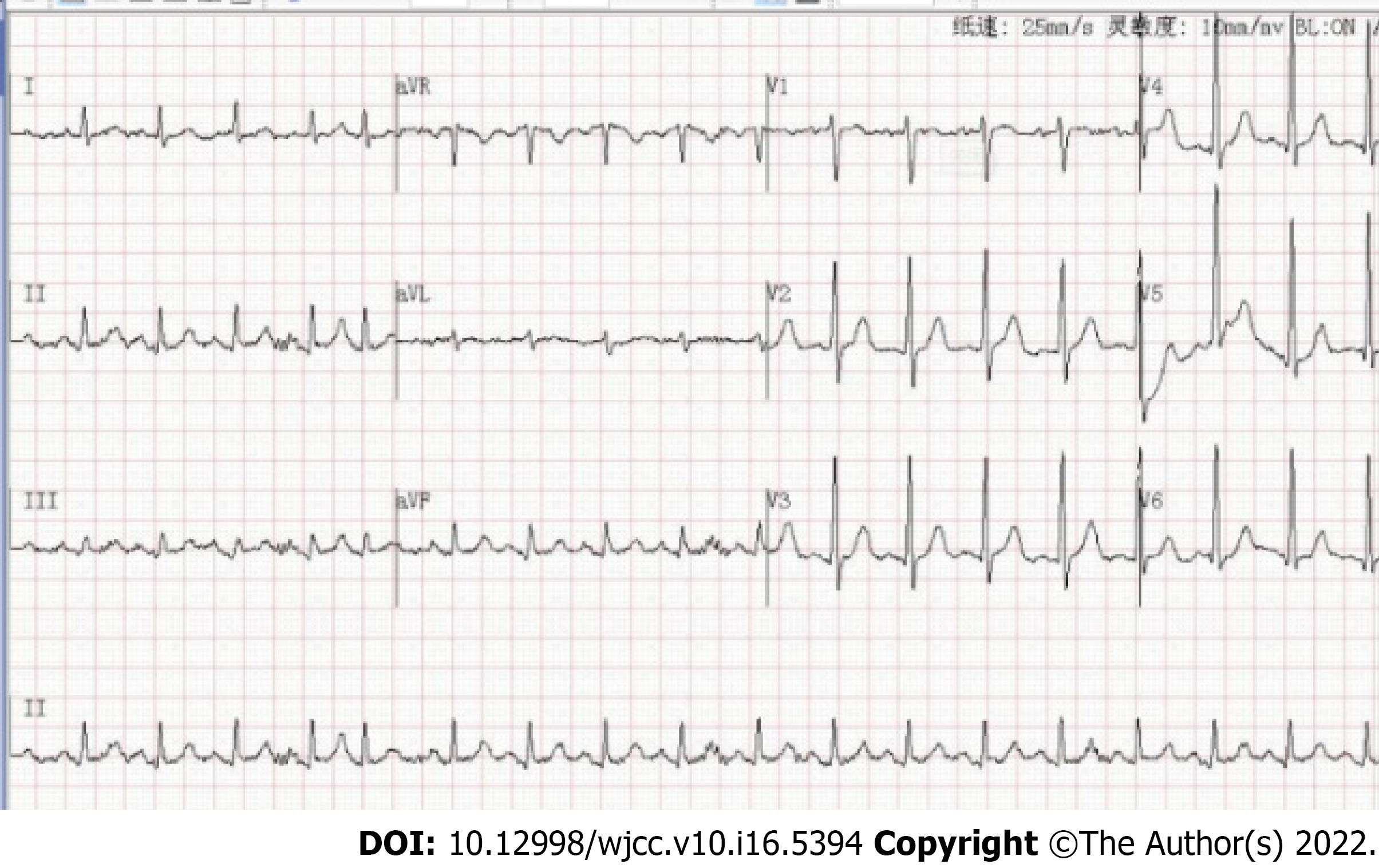

Admission examination of the head, chest and abdomen by computed tomography revealed a subdural hemorrhage, multiple rib fractures, a hemopneumothorax and a renal hematoma. After 2 wk, computed tomography angiograms (CTAs) of his chest and abdomen were then collected, which revealed a type B AD located across the aortic arch to the renal artery (Figure 1A-D), a left lower lobe PE (Figure 1E-F), and a superior mesenteric artery thrombus (Figure 1G-H). Subsequent cardiac ultrasound assessed pulmonary artery pressure at 40 mmHg, right ventricular end-diastolic internal diameter at 28 mm, left atrial internal diameter at 38 mm, left ventricular end-diastolic internal diameter at 62 mm, left ventricular ejection fraction at 54%, no thrombus on lower limb vascular ultrasound, and an electrocardiogram of sinus tachycardia (Figure 2).

Stanford type B aortic coarctation combined with pulmonary embolism.

He was admitted to the Emergency Intensive Care Unit and given a combination of oxygen therapy, external rib fixation, analgesia and enteral nutrition. 2 wk later, he was found to have both AD and PE by CTA. PE and superior mesenteric artery thrombosis require anticoagulation; however, in the acute phase of AD, there is a risk of exfoliation and rupture, which is a contraindication to anticoagulation. Initially, we proposed vascular surgery or interventional treatment of AD followed by anticoagulation, but this option was rejected by the patient's family. We subsequently performed only nonsurgical treatment, including nasal high-flow oxygen therapy (FiO2 50%, 50 L/min), nonsteroidal analgesia, amlodipine for blood pressure control, beta-blockers for heart rate control, thoracentesis drainage to improve dyspnea, and antibiotics to treat pulmonary infection complications; ultimately, he did not receive any anticoagulation therapy.

Eight weeks after admission, the patient's abdominal pain and dyspnea improved significantly, hypoxemia was corrected, and he was discharged in good condition. He reported no other symptoms during the 6-mo follow-up period.

The coexistence of AD and PE in the same patient is not common, and only a limited number of cases have been reported[2,3]. The mechanism underlying the simultaneous development of AD and PE remains unclear, and various factors may contribute to such a comorbidity. One likely cause of this simultaneous occurrence is the close anatomical relationship between them, where compression of the right pulmonary artery induced by AD can cause the stagnation of blood flow that may lead to PE[2,4-8]. Another plausible cause is that deep vein thrombosis occurring in the lower extremities may travel up to the pulmonary artery and cause PE. Finally, the occurrence of AD can trigger a widespread coagulation response that results in multiple thromboses traveling throughout the circulatory system. In the present case, the patient had thrombosis in both the left lower pulmonary artery and the superior mesenteric artery, while no thrombus was found in other sites, such as the lower extremity vessels. Because the locations of the left lower pulmonary and superior mesenteric artery thrombi were adjacent to the location of the aortic hematoma, we speculate that thrombosis was likely caused by the stagnation of blood flow after compression of the corresponding vessels.

The simultaneous occurrence of AD and PE often leads to contradictory treatment strategies, and there is currently no standard treatment. In a recently reported case of concurrent type B AD and PE[9], conventional treatments did not result in a positive outcome. However, the patient was successfully treated with more complex approach involving thoracic endovascular aortic repair and a stent graft. Nevertheless, another reported case with both PE and AD was successfully treated with conventional therapies, as was done in the current report[10]. Previous reports[7] have indicated that successful emergency surgery can be administered for concurrent type A: AD and hematoma to relieve compression of the pulmonary artery. In summary, the adverse consequences of bleeding and thrombosis should be weighed against the treatment of AD combined with PE. This patient had both AD and PE but was fortunate to have low-risk PE risk stratification; although he did not receive anticoagulation, his PE gradually improved as the AD was controlled and the overall condition continued to improve.

In conclusion, patients with AD should be alerted to the possibility of combined PE, the development of which may be associated with aortic compression. In patients with type B: AD combined with low-risk PE, a nonsurgical treatment plan without anticoagulation and appropriate oxygen therapy support, along with heart rate and blood pressure control, may be feasible.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Emergency medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kharlamov AN, Netherlands; uz Zaman M, Pakistan S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Suzuki T, Mehta RH, Ince H, Nagai R, Sakomura Y, Weber F, Sumiyoshi T, Bossone E, Trimarchi S, Cooper JV, Smith DE, Isselbacher EM, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA; International Registry of Aortic Dissection. Clinical profiles and outcomes of acute type B aortic dissection in the current era: lessons from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation. 2003;108 Suppl 1:II312-II317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Buja LM, Ali N, Fletcher RD, Roberts WC. Stenosis of the right pulmonary artery: a complication of acute dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta. Am Heart J. 1972;83:89-92. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Elmali M, Gulel O, Bahcivan M. Coexistence of pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, and persistent left superior vena cava in the same patient. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2008;9:1180-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Charnsangavej C. Occlusion of the right pulmonary artery by acute dissecting aortic aneurysm. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;132:274-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sorensen B, Moyal C, Marlois O, Vaisse B, Montiès JR, Poggi L. [Compression of the right pulmonary artery by a dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta. Apropos of a case occurring long after aortic valve replacement]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1986;79:1111-1115. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Worsley DF, Coupland DB, Lentle BC, Chipperfield P, Marsh JI. Ascending aortic dissection causing unilateral absence of perfusion on lung scanning. Clin Nucl Med. 1993;18:941-944. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Neri E, Toscano T, Civeli L, Capannini G, Tucci E, Sassi C. Acute dissecting aneurysm of the ascending thoracic aorta causing obstruction and thrombosis of the right pulmonary artery. Tex Heart Inst J. 2001;28:149-151. [PubMed] |

| 8. | De Silva RJ, Hosseinpour R, Screaton N, Stoica S, Goodwin AT. Right pulmonary artery occlusion by an acute dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;1:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dong ZC, Hua YZ. Pulmonary Embolism and Stanford Type B Aortic Dissection in the Same Patient. JVMS. 2015;3:226. |

| 10. | Tudoran M, Tudoran C. High-risk pulmonary embolism in a patient with acute dissecting aortic aneurysm. Niger J Clin Pract. 2016;19:831-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |