Published online Jun 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5343

Peer-review started: July 18, 2021

First decision: October 16, 2021

Revised: November 4, 2021

Accepted: April 26, 2022

Article in press: April 26, 2022

Published online: June 6, 2022

Processing time: 318 Days and 19.6 Hours

Mammary-type myofibroblastoma (MTMF) is a rare benign extramammary soft tissue tumor with myofibroblastic differentiation. Although 160 cases of MTMF have been reported in the literature since 2001, no cases of infarction or atypical mitosis have been reported so far. Herein, we report an unusual case of MTMF in the pelvic cavity, which mimicked some malignant features, including infarction, atypical mitosis, infiltrative growth, and prominent cytologic atypia, making it difficult to ascertain whether the tumor was benign.

A 49-year-old man complained of pain and discomfort in the right buttock for more than 4 mo and did not receive any treatment. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 13-cm-sized mass in his right pelvic cavity. Histologically significant differences were atypical mitosis figures and multiple necrotic foci in the tumor. In addition, smooth muscle and skeletal muscle were invaded within and at the edge of the tumor. These morphologic features are often reminiscent of malignant tumors and therefore pose a diagnostic challenge to pathologists. The tumor cells were strongly positive for both cluster of differentiation 34 and desmin, and the loss of retinoblastoma 1 shown by immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization results confirmed the pathological diagnosis of MTMF. Currently, the patient is alive and in good condition without tumor recurrence or metastasis after 2.5 years of follow-up by telephone and MRI.

The two pseudo-malignant characteristics of infarction and atypical mitosis broaden the morphological lineage of MTMF, a rare mesenchymal tumor.

Core Tip: Mammary-type myofibroblastoma (MTMF) is a rare extra-mammary soft tissue tumor with myofibroblast differentiation. Since 2001, more than 160 cases have been reported in the literature. Almost all reports have identified MTMF as a benign tumor except for three cases of recurrence. Here, we report a case of MTMF, which mimicked some malignant features, such as infarction, atypical mitosis, infiltrative growth, and cytologic atypia. Although infiltrative growth and cytological atypia have been reported in previous cases, there are no reports of infarction and atypical mitosis in MTMF, and this is the first report that these pseudo-malignant features appear simultaneously in the same case. Taken together, these characteristics pose a diagnostic pitfall that must be avoided. The purpose of this report is to alert pathologists if they encounter a tumor with these pseudo-malignant features and myofibroblastic differentiation, they must not forget that they need to rule out the diagnosis of MTMF first.

- Citation: Zeng YF, Dai YZ, Chen M. Mammary-type myofibroblastoma with infarction and atypical mitosis-a potential diagnostic pitfall: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(16): 5343-5351

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i16/5343.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5343

Mammary-type myofibroblastoma (MTMF) is a rare, benign mesenchymal neoplasm occurring outside the breast that was first described in 2001[1]. The histological morphology of the lesion resembles myofibroblastoma in the breast, which was first reported in 1987[2]. It is usually well-circumscribed, encapsulated or unencapsulated, and composed of haphazardly arranged fascicles of spindle cells admixed with various amounts of adipocytes in a collagenous, hyalinizing, or myxoid background[3,4]. In immunohistochemical (IHC) results, the spindle cells often characteristically express both cluster of differentiation 34 (CD34) and desmin (Des)[1,4,5]. Genetically, MTMF belongs to “the 13q/retinoblastoma (Rb) family of tumors”, which are featured by deletion or rearrangement of the 13q14 region, resulting in loss of the Rb gene and Rb protein expression[4,6,7]. MTMF was almost always reported as a benign mesenchymal neoplasm, except in three recurring cases[4,8], one of which recurred due to positive excision margins[8].

Although cytologic atypia and the aggressive growth of tumor cells can be found in some cases in the literature[4,9,10], infarction and atypical mitosis inside the tumor have never been reported so far. Herein, we report a case of MTMF in the buttock that mimicked some pseudo-malignant features, including infarction, atypical mitosis, infiltrative growth, and prominent cytologic atypia, making it difficult to ascertain whether the tumor was benign. The purpose of this report is to remind pathologists to be alert for this potential diagnostic pitfall.

A 49-year-old man was admitted to Jiangxi Provincial People’s Hospital (the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College, Nanchang, China) with a mass in his right buttock for 4 mo.

There was nothing significant about the patient’s present medical history.

The patient had a history of sacrococcygeal trauma 3 years before admission, and there were no other abnormalities.

In terms of personal and family history, there was nothing of note.

There was no abnormality except the fullness in the right rectal wall found during the special anal examination.

No obvious abnormality was found in the serum tumor markers.

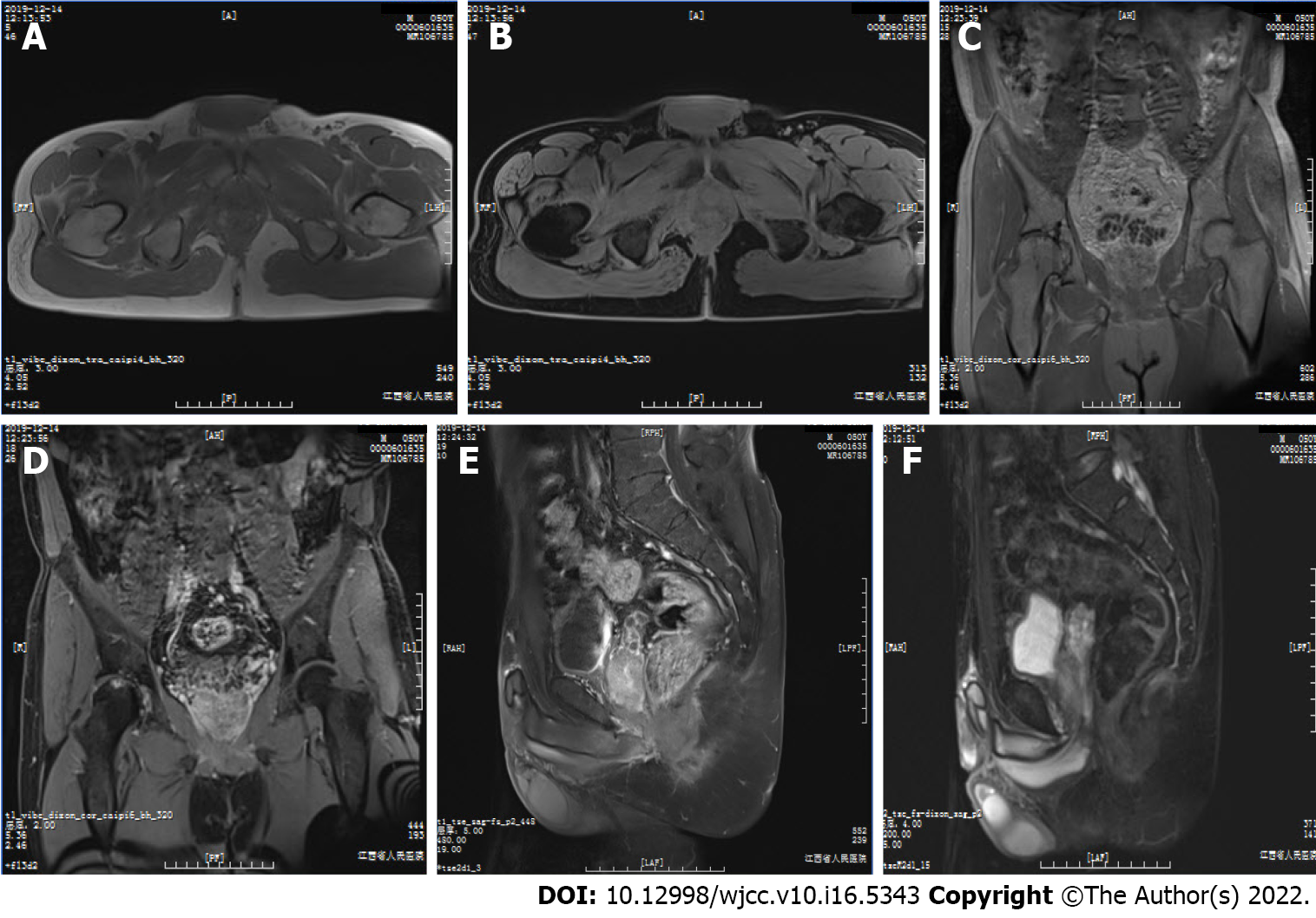

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large, well-defined mass located slightly to the right in the center of the pelvic cavity between the left and right obturator muscles (Figures 1A and 1B). The mass appeared predominantly positioned in the area deep to the gluteus maximus, posterior to the pubic symphysis, underneath the bladder, and above the urogenital septum (Figures 1C and 1D). It displaced the prostate and seminal vesicle glands to the upper left (Figures 1E and 1F) and pushed the rectum and anal canal close to the left pelvic wall (Figure 1B). The mass displayed predominantly isointense T1 signal, which was related to the surrounding musculature (Figures 1A and 1C) and heterogeneous on fat-suppressed T1 (T1FS; Figures 1B, 1D, and 1E) and T2 (T2FS; Figure 1F) imaging. There was intralesional focal necrosis and perilesional edema (Figures 1E and 1F).

The mass was surgically excised. During surgery, it was found to be well-circumscribed and with an incomplete capsule and poor mobility, giving a clinical impression of a malignant tumor. Its upper margin reached the seminal-vesicle gland, and the outer edge closely adhered to the right part of the external rectal sphincter, levator ani, and puborectal muscles, but no nerve, vessel, or inguinal lymph node invasion was found.

On gross examination, the mass was 13 cm × 12 cm × 8 cm in size, and covered by an incomplete capsule and the remnants of adipose tissue (Figure 2A). The cut surface showed a solid, firm-to-elastic, and yellow-pink appearance, with focal cystic degeneration and necrosis within the mass (Figure 2B). Histologically, the tumor had a definite capsule (Figure 3A); it was composed of short spindle- to oval-shaped cells and admixed with varying thick bundles of collagen and variable numbers of adipocytes (Figure 3B). The cells had eosinophilic cytoplasm with indistinct cell borders and had elongated nuclei with fine chromatin (Figure 3B). Hyaline (Figure 3C) and mucoid (Figure 3D) degeneration were visible within the tumor. Atypic and bizarre cells could be seen in some areas (Figure 3E). It is worth noting that mitotic figures (Figure 3F), even atypical mitosis (Figure 3G), and multiple necrotic foci and nuclear debris (Figure 3H) could be seen in the tumor. In addition, smooth muscle (Figures 3I and 3J) and skeletal muscle (Figures 3K and 3L) were invaded within and at the edge of the tumor. These morphological features are often reminiscent of malignant tumors and therefore pose a severe diagnostic challenge to pathologists.

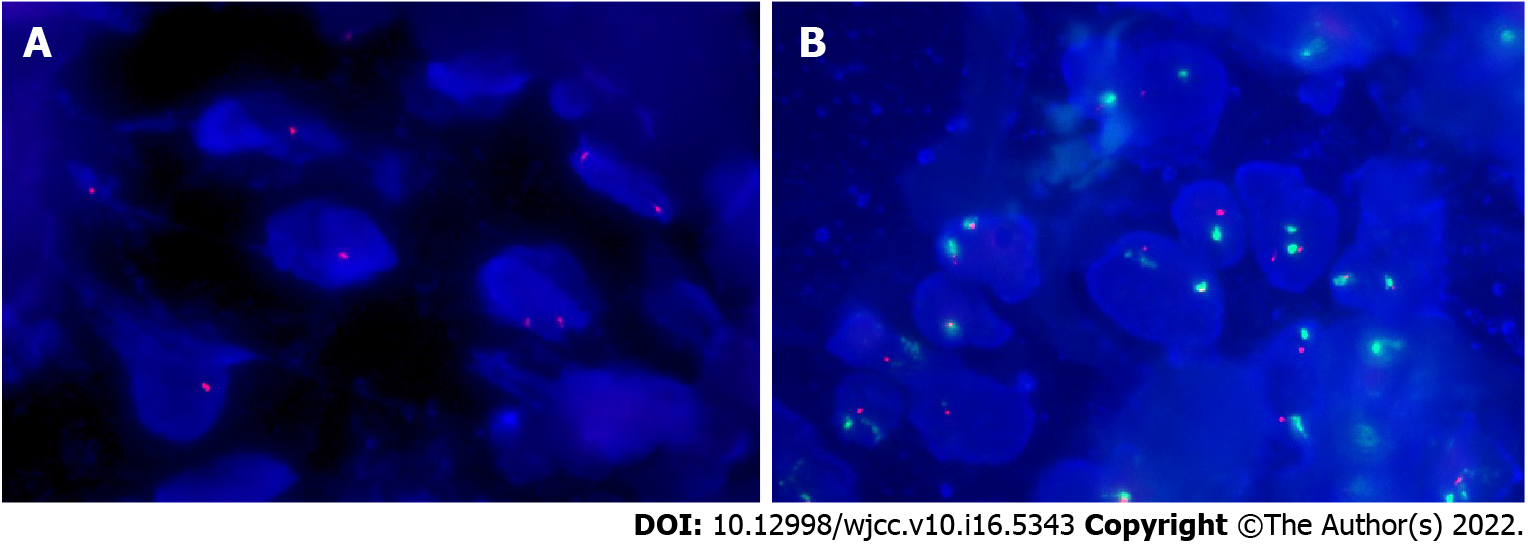

IHC staining showed that these neoplastic cells were strongly positive for both CD34 and Des (Figures 4A and 4B), and had lost expression of Rb1 protein (Figure 4C). In addition, they showed positive expression of estrogen receptor, epithelial-membrane antigen, human homolog of murine double minute 2 (MDM2), and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) (Figures 4D-G). However, they were negative for S100, smooth muscle actin (SMA), signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6), and CD117 (Figures 4H-K). The proliferation index of these neoplastic cells was about 5%, as shown by Ki-67 IHC staining (Figure 4L). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) confirmed the monoallelic and biallelic deletion of the Rb1 (Figure 5A) and no amplification of MDM2 (Figure 5B) in these neoplastic cells.

The preoperative clinical diagnosis was malignant mesenchymal tumor of the pelvic cavity.

Based on the above pathological, IHC, and FISH results, the final diagnosis was MTMF.

The patient did not receive any treatment after operation.

The patient was followed for 2.5 years by telephone and MRI, and no recurrence or metastasis was found. Figure 6 shows the follow-up MRI scan of the patient’s pelvic cavity, at 6 mo post-operation. T1-weighted image (T1WI; Figure 6A), T1FS image (Figure 6B), coronal T1WI (Figure 6C), coronal T1FS image (Figure 6D), sagittal T1FS image (Figure 6E), and sagittal T2FS image (Figure 6F) showed complete removal of the mass, with normal diffusion in the patient’s pelvic cavity. There were no abnormalities except the abnormal signals from the right acetabulum and femoral head, and the ischemic necrosis of the head was considered. The size and position of pelvic visceral organs, such as the prostate, seminal vesicle, and rectum, were normal, and the bladder was well filled.

MTMF, proposed as an independent entity in 2001, is a very rare, benign, mesenchymal tumor occurring outside the breast. So far, more than 160 cases have been reported[2,4,5]. Adults aged 40-60 years are predisposed to MTMF, with men predominating slightly[4]. The tumor has extensive anatomic distribution; the groin and inguinal regions might be the most common sites[4,5]. Clinically, MTMF usually presents as a painless, slowly growing mass. The lump is well-circumscribed, firm, and 1-34 cm in size, with a pale-yellow or grayish-brown cut surface[2-4]. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of short spindle and oval-shaped cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and fine chromatin. In a few cases, the cells are epithelioid[4,9]. Cells are arranged irregularly or in a palisade pattern similar to schwannoma, with collagen bundles in the stroma[4,11]. Various adipocytes and mast cells are seen in the stroma as well[3,4]. The blood vessels in the interstitium seem to be less visible, surrounded by infiltrating lymphocytes. In some cases, the stroma can be accompanied by hyalinization or myxoid degeneration[12,13].

The buttock is a rare anatomical site for MTMF. Except for our case, only two cases have been reported in the buttock so far[1,14]. Moreover, in addition to the morphological characteristics described above, the mass in our case also simulated some characteristics of malignant tumors, including infarction, atypical mitosis, infiltrative growth, and cytological atypia. These can pose diagnostic traps for pathologists. Nonetheless, infiltrative growth and atypical cytological findings, including degenerative nuclei, polynuclei, hyperchromatic nuclei, and bizarre nuclei, have been reported in previous cases[4,9]. However, there are no reports of infarction or atypical mitosis in MTMF. This is the first report of these two pseudo-malignant features appearing simultaneously in the same case. It is unclear whether these phenotypes suggest that the tumor has a certain malignant potential. After all, the > 160 previous case reports feature only three relapses[4,8], although one of them was due to positive margins[8].

Next, we will discuss differential diagnosis of MTMF. Like MTMF, cellular angiofibroma (CA) and spindle cell lipoma (SCL) have the same abnormal 13q/Rb genetic changes and morphological overlap and similarity, which suggest that MTMF, CA, and SCL might be tumors of the same lineage[6]. Nevertheless, these tumors have subtle differences in morphology. Unlike MTMF, CA is usually confined to the groin area, and contains a prominent component of round vessels in the stroma, often accompanied by vascular-wall fibrosis and hyalinization. Moreover, CA has few adipocytes, and has wispy rather than thick collagen[4,6,7]. Generally, the CA spindle cells are positive for vimentin and negative for Des and CD34. All of these findings are helpful for differential diagnosis of CA from MTMF. SCL and MTMF are both composed of spindle cells admixed with mature adipose tissue, and both share a CD34-positive immunophenotype[7]. SCL mainly occurs in the posterior shoulder and neck or the upper back[6,7]; contains more-consistent, ropey, refractile collagen bundles, and adipose tissue; and does not stain for Des while almost always expressing CD34[4]. However, the overlapping morphologies of SCL, CA, and MTMF, combined with shared genetic alteration, raises the point that these tumors might belong to a single spectrum of the 13q/Rb family rather than be distinct entities[4,6].

Other differential diagnoses including spindle cell liposarcoma, atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumor (ASCLT), and the “fat-forming” variant of solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) should all be considered. Spindle cell liposarcoma, which belongs to the well-differentiated liposarcoma family, is composed of fibroblast-like spindle cells arranged in bundles plus lipomatous liposarcoma. The tumor cells express S100, MDM2, and CDK4 proteins; amplification of MDM2 can be detected via molecular genetics[15], which can distinguish this tumor from MTMF. ASCLTs consist of adipose-differentiated spindle cells, which are positive for S100 as well as CD34 on IHC[16], and can be differentiated from MTMF. Nevertheless, in terms of genetics, there is no MDM2 amplification but rather loss of Rb1 in 57% of ASCLT cases[16]. MTMF might need differential diagnosis from SFT, especially the “fat-forming” variant of the latter. Although SFTs share CD34-positive immunostaining with MTMF, they specifically express another sensitive marker, STAT6, which results from rearrangement of STAT6[17]. Moreover, FISH shows no Rb1 loss in SFTs.

This case report documents an MTMF with certain pseudo-malignant characteristics, including tumor infarction, atypical mitosis, aggressive growth patterns, and cytological atypia. Taken together, these characteristics pose a diagnostic pitfall that must be avoided. The purpose of this report is to alert pathologists if they encounter a tumor with these pseudo-malignant features and myofibroblastic differentiation, they must not forget that they need to rule out the diagnosis of MTMF first.

We thanks for Professor Jian Wang, who comes from the Department of Pathology, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Fudan University, for providing assistance in diagnosis and immunohistochemical staining of Rb1 protein and thank Anbiping for providing in situ hybridization detection probes and technical support for detecting Rb and MDM2 genes.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bianchi F, Spain S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | McMenamin ME, Fletcher CD. Mammary-type myofibroblastoma of soft tissue: a tumor closely related to spindle cell lipoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1022-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wargotz ES, Weiss SW, Norris HJ. Myofibroblastoma of the breast. Sixteen cases of a distinctive benign mesenchymal tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:493-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abdul-Ghafar J, Ud Din N, Ahmad Z, Billings SD. Mammary-type myofibroblastoma of the right thigh: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Howitt BE, Fletcher CD. Mammary-type Myofibroblastoma: Clinicopathologic Characterization in a Series of 143 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:361-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ishihara A, Yasuda T, Sakae Y, Sakae M, Hamada T, Tsukazaki H, Tsukazaki T, Furumoto M. A case of mammary-type myofibroblastoma of the inguinal region. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:464-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Maggiani F, Debiec-Rychter M, Vanbockrijck M, Sciot R. Cellular angiofibroma: another mesenchymal tumour with 13q14 involvement, suggesting a link with spindle cell lipoma and (extra)-mammary myofibroblastoma. Histopathology. 2007;51:410-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Maggiani F, Debiec-Rychter M, Verbeeck G, Sciot R. Extramammary myofibroblastoma is genetically related to spindle cell lipoma. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:244-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nguyen BD. Large abdominopelvic mammary-type myofibroblastoma with incomplete resection and recurrence. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McMenamin ME, DeSchryver K, Fletcher CD. Fibrous Lesions of the Breast: A Review. Int J Surg Pathol. 2000;8:99-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alizadeh L, Alkhasawneh A, Reith JD, Al-Quran SZ. Epithelioid Myofibroblastoma of the Breast: A Report of Two Cases with Discussion of Diagnostic Pitfalls. Breast J. 2015;21:669-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Magro G, Foschini MP, Eusebi V. Palisaded myofibroblastoma of the breast: a tumor closely mimicking schwannoma: Report of 2 cases. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1941-1946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Magro G. Mammary myofibroblastoma: a tumor with a wide morphologic spectrum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1813-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Magro G, Salvatorelli L, Spadola S, Angelico G. Mammary myofibroblastoma with extensive myxoedematous stromal changes: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210:1106-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arsenovic N, Abdulla KE, Shamim KS. Mammary-type myofibroblastoma of soft tissue. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:391-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hostein I, Pelmus M, Aurias A, Pedeutour F, Mathoulin-Pélissier S, Coindre JM. Evaluation of MDM2 and CDK4 amplification by real-time PCR on paraffin wax-embedded material: a potential tool for the diagnosis of atypical lipomatous tumours/well-differentiated liposarcomas. J Pathol. 2004;202:95-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mentzel T, Palmedo G, Kuhnen C. Well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma ('atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumor') does not belong to the spectrum of atypical lipomatous tumor but has a close relationship to spindle cell lipoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of six cases. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:729-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tai HC, Chuang IC, Chen TC, Li CF, Huang SC, Kao YC, Lin PC, Tsai JW, Lan J, Yu SC, Yen SL, Jung SM, Liao KC, Fang FM, Huang HY. NAB2-STAT6 fusion types account for clinicopathological variations in solitary fibrous tumors. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:1324-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |