Published online Jun 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5306

Peer-review started: March 20, 2021

First decision: July 15, 2021

Revised: August 23, 2021

Accepted: April 30, 2022

Article in press: April 30, 2022

Published online: June 6, 2022

Processing time: 439 Days and 0.4 Hours

Parental drinking has a direct bearing on children. Behavioral problems such as anxiety and depression are common problems among children whose parents drink heavily. Psychosocial interventions have shown promising results for anxiety and depression among children; however, few studies have been conducted in the context of children of parents with alcohol dependence in India.

To evaluate the efficacy of psychosocial intervention for internalizing behavioral problems among children of parents with alcohol dependence.

A randomized controlled trial with a 2 × 4 factorial design was adopted with longitudinal measurement of outcomes for 6 mo. Two-hundred and eleven children who met the eligibility criteria (at least one parent with alcohol dependence) at government high schools in Bangalore, India, were randomized to the experimental (n = 97) or control group (n = 98). The psychosocial intervention was administered to the experimental group in eight sessions (biweekly) over 4 wk after baseline assessment. The intervention focused on identifying and modifying negative thoughts, replacing thinking errors with realistic alternatives, modification of maladaptive behavior, developing adaptive coping skills and building self-esteem. The data was collected pre-intervention and at 1, 3 and 6 mo after the intervention. Data were analyzed using SPSS 28.0 version.

Mean age of the children was 14.68 ± 0.58 years, 60.5% were male, 56% were studying in 9th standard, 70.75% were from nuclear families, and mean family monthly income was 9588.1 ± 3135.2 INR. Mean duration of parental alcohol dependence was 7.52 ± 2.94 years and the father was the alcohol-consuming parent. The findings showed that there were significant psychosocial intervention effects in terms of decreasing anxiety and depression scores, and increasing self-esteem level among experimental group subjects over the 6-mo interval, when compared with the control group (P < 0.001).

The present study demonstrated that the psychosocial intervention was effective in reducing anxiety and depression, and increasing self-esteem among children of parents with alcohol dependence. The study recommends the need for ongoing psychosocial intervention for these children.

Core tip: The burden of internalizing behavioral problems among children of alcohol-dependent parents in India calls for the immediate attention of health professionals. The health programs existing in India mainly focus on alcohol-using individuals; however, the children need interventions in view of various negative sequelae of familial alcohol use. The present study is a preliminary attempt in this direction. Internalizing behavioral problems can be reduced by using psychosocial intervention based on group cognitive–behavioral approaches.

- Citation: Omkarappa DB, Rentala S, Nattala P. Effectiveness of psychosocial intervention for internalizing behavior problems among children of parents with alcohol dependence: Randomized controlled trial. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(16): 5306-5316

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i16/5306.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5306

Alcohol is a psychoactive substance that is commonly consumed by Indians. About 14.6% of the Indian population between the ages of 10 and 75 years use alcohol[1]. It is a well acknowledged fact that heavy alcohol use afflicts not only the individual but also the whole family. The literature suggests that adults’ drinking is associated with physical and psychological harms to children[2]. Children of alcohol users are likely to suffer from various behavioral problems as well. These can be grouped into internalizing behavioral problems such as anxiety, depression or suicidal ideas, and externalizing outward behaviors[3,4]. Internalizing disorders are common mental health concerns among children and adolescents[5,6]. Studies conducted in India have reported that children of parents with alcohol use are at risk for having higher internalizing behavioral problems such as fear, insecurity, hopelessness, guilt feeling, shame, lack of trustworthy feeling, anxiety disorders, depression, low self-esteem, ambivalent behavior, confusion about life goals, poor adjustment, compulsive behaviors, withdrawal from other children, difficulty concentrating, and poor grades in school[7,8]. Parental alcohol dependence also affects the development of social competence among children[9]. A recent study involving school children reported 45% of the study sample as suffering from various harmful effects that were directly attributable to others’ alcohol misuse, including their fathers[10].

Given the exponential rise in use of alcohol in India and increasing number of children growing up in such homes, there is an urgent need for evidence-based interventions to reduce the harms associated with parental drinking among children in India[2]. Psychoanalysis, family therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy are some interventions that have been used to treat a child’s internalizing disorders. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) among these is the most widely used intervention program that is well supported by empirical evidence[11-13]. CBT is based on the assumption that feelings and behaviors are a result of recognition. A number of studies have shown group CBT is effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression and other mental health problems among children. CBT helps children to identify the link between cognition, behavior and emotions, thereby modifying maladaptive behavior and irrational beliefs. It can also be delivered by a trained community health care person[14-17].

Empirical evidence indicates that school-based and community-based prevention programs are effective in preventing depression, anxiety, or both in high-risk children and adolescents[18,19]. In India, most of the adolescent population can be approached through schools and colleges. Recent WHO reports indicate the importance of health services to schools as they play an important role in promoting healthy behavior among the younger generation[20]. Among these services, school nurses play an important role in promoting health, improving academic performance, reducing absenteeism and school dropout, and helping in the identification and management of psychiatric illnesses[21,22].

In western countries, school nurses play an important role in the treatment and prevention of common mental health problems among school children. School nurses implement different forms of psychotherapy and act as therapists to reduce behavioral problems among children. However, in India, school nurses limit themselves to delivery of only basic services. School is an ideal location for delivering group therapy as children with common problems can be gathered and needed interventions can be provided. Studies also indicate that school-based intervention is effective in reducing behavioral problems[18,19].

The burden of internalizing behavioral problems among children of alcoholic parents in India calls for the immediate attention of health professionals. While alcohol use in the family is established to have harmful effects on children, health services in India have by and large focused on the alcohol using individual. Hidden problems among such children should be addressed so as to prevent complications in adulthood. As only a few Indian studies have been conducted in this direction, the present study was conceived to find out the efficacy of a cognitive–behavioral psychosocial intervention on internalizing behavioral problems among children of alcohol using parents at a school setting. It was hypothesized that children who undergo the psychosocial intervention will show significantly improved outcomes in terms of increased self-esteem, and decreased anxiety and depression levels, when compared with a control group.

A randomized controlled trial with a 2 × 4 factorial design was adopted with longitudinal measurement of outcomes for 6 mo.

Participants were recruited from 12 government high schools located in Bangalore South-II Taluk, which cover three constituencies namely, Chamrajpet, Vijayanagar and Govindarajnagar. Formal permission was obtained from the concerned area Block Education Officer and head teachers of the schools for conducting the study. The data were collected from September 2017 to April 2018.

Sample and sample size: The sampling inclusion criteria were: (1) Children of alcohol-dependent parents and having behavioral problems [screened using Paediatric Symptom Checklist: Youth Report (Y-PSC)]; and (2) Aged 12–16 years and able to converse, read and write in Kannada or English. Parental alcohol dependence was confirmed by interviewing the parents based on ICD-10 criteria. The study excluded children with learning disabilities, history of seizures, head injury, unconsciousness, other major health problems in the last 2 years (as reported by the parents). Also, children of single parents were excluded.

A pilot study was conducted to determine the appropriate sample size for the main study. G*Power 3.1.9.2 software program was used to calculate the sample size by keeping the power of study at 80% (P < 0.05, two tailed). The calculated sample size was 182 for both groups, which was sufficient to achieve statistical significance for depression, anxiety and self-esteem. Considering the possibility of dropout, 211 children were recruited for the study.

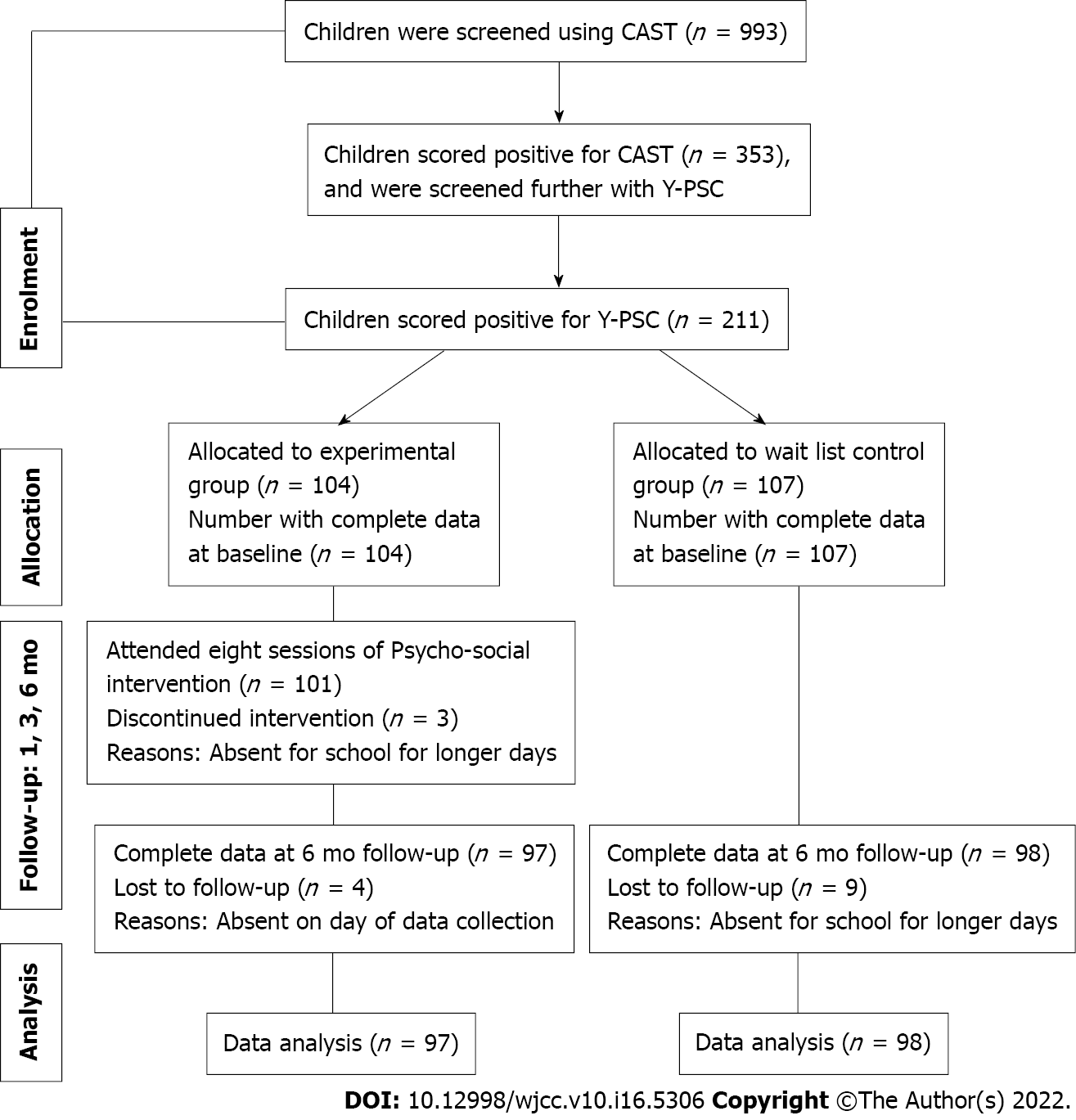

Recruitment: There were 993 children in the schools aged 12–16 years, who were screened using modified Children of Alcoholic Screening Test (CAST) and Y-PSC. Out of the 211 children who met the eligibility criteria, 104 were randomly allocated to the experimental group and 107 to a waiting list control group. At the final assessment, 195 children were present, as 13 children were lost to follow-up in both group and three children in the experimental group discontinued the intervention (Figure 1).

Intervention: The psychosocial intervention was developed based on the group CBT approach specifically for internalizing behavioral problems among children of alcohol-dependent parents. The eight sessions focused on developing skills in identifying and modifying negative thoughts, replacing thinking errors with realistic alternatives, modification of maladaptive behavior, developing adaptive coping skills, and building self-esteem. Content validity of the CBT intervention was established by obtaining the inputs of experts in the field of substance use disorders and their management.

The intervention protocol was categorized into eight sessions with specific objectives and techniques (Table 1). Participants in the experimental group underwent the group-based CBT spread over 4 wk. The intervention was administered using a group approach by the first author, who is an experienced psychiatric nurse with a Master’s degree in psychiatric nursing and received CBT training at a tertiary mental health care center. Each group consisted of 8–10 children. The intervention consisted of weekly 2-h sessions for 4 wk. Each session began with a structured agenda, and a homework assignment at the end of the session to apply particular skills and concepts from the session.

| Session | Techniques (methods) | Personal projects |

| I: Initiating therapeutic process | (1) Mini-lecture on effects of alcoholism; (2) Group discussion; (3) In session practice-list the effects of alcoholism on their family; (4) Relaxation exercises; and (5) Psychoeducation | (1) Mood thermometer; and (2) Practice deep breathing exercises |

| II: Identifying negative thoughts | (1) Mini-lecture on positive and negative thoughts; (2) In session practice list of positive and negative thoughts; and (3) Relaxation exercises | (1) Mood thermometer; (2) List of positive and negative thoughts; (3) Practice deep breathing exercises; and (4) Practice progressive muscle relaxation |

| III: Identifying thinking errors | (1) Mini-lecture on thinking errors; (2) Group discussion on common thinking errors; (3) In session practice–categorizing negative thoughts into suitable cognitive distortions; and (4) Relaxation exercises | (1) Mood thermometer; (2) Continue to list positive and negative thoughts; (3) Practice deep breathing exercises and progressive muscle relaxation; and (4) Work sheet for recoding thinking errors |

| IV: Cognitive restructuring | (1) Mini-lecture on distraction techniques; (2) In session practice–converting negative thought into positive thought; and (3) Relaxation exercises | (1) Mood thermometer; (2) Practice some of strategies discussed to improve positive thoughts; (3) Practice deep breathing exercise, progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery; and (4) Work sheet for recoding thinking errors |

| V: Untwisting negative thinking | (1) Mini-lecture on 10 ways of untwisting negative thinking; (2) In session practice–challenging cognitive distortions; (3) Group discussion on rational thinking; and (4) Relaxation exercises | (1) Mood thermometer; (2) Practice some of strategies discussed to challenge cognitive distortions; (3) Practice deep breathing exercise, progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery; and (4) Challenging cognitive distortions |

| VI: Behavioral activation | (1) Mini-lecture on scheduling pleasurable activities and how to mastery over those activities; (2) In session practice-list of pleasant activities; (3) Relaxation exercises; and (4) Group discussion on healthy lifestyle. | (1) Mood thermometer; (2) Practice deep breathing exercise, progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery; (3) List of pleasant activities; and (4) Weekly schedule for behavioral activation |

| VII: Effective coping mechanism | (1) Problem solving game; (2) Mini-lecture on coping mechanism and expression of emotions in healthy way; and (3) Relaxation exercises | (1) Mood thermometer; (2) Practice all relaxation exercises; (3) List of pleasant activities; and (4) Weekly schedule for behavioral activation |

| VIII: Social skills and assertiveness | (1) Mini-lecture on social skills and assertiveness; (2) Relaxation exercises; and (3) Group sharing on activities learned in each session | Practice techniques learned in all sessions |

Following the last session of the intervention, all the participants were followed up at 1, 3 and 6 mo in the respective schools.

Measures: CAST-6: The CAST, developed by Jones and Pilat, was used to screen for the presence of parental alcohol use. The internal consistency of CAST-6 ranges from 0.86 to 0.92 (Cronbach’s α)[23]. If the child answered ‘Yes’ to at least three of the items, it indicated parental alcohol use. Prior Indian studies have used this scale to screen for the presence of parental alcohol use[7,9].

Y-PSC (Murphy et al[24], 1988): The Y-PSC facilitates the recognition of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral problems. The Y-PSC consists of 35 items rated as “Never,” “Sometimes” or “Often” present, and scored 0, 1 or 2, respectively. The score ranges from 0 to 70, with a cut-off score of 30 or higher indicating impaired psychosocial functioning. Test–retest reliability of the PSC ranges from r = 0.84 to 0.91 and internal consistency of the PSC using Cronbach α is 0.91[24]. Prior Indian studies have utilized this scale to assess behavioral problems among children[25,26].

Rosenberg self-esteem scale: Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale which contains 10 items in a four-point Likert scale format. A score less than 20 indicates low self-esteem, 20–30 indicates moderate self-esteem, and above 30 indicates high self-esteem. Prior studies show that the scale had high internal consistency (α = 0.72–0.87), and test–retest reliability for the 2-wk interval was 0.85, and for the 7-mo interval, 0.63[23,27]. Prior Indian studies have used this scale to measure global self-worth[4,7]. Reliability for the present study was established by test–retest method(α = 0.91) and split-half method (α = 0.81).

Spence children’s anxiety scale (SCAS): Participants’ anxiety was assessed using the SCAS, a four-point Likert scale containing 38 items related to anxiety, with higher scores representing severe anxiety. Reliability for the SCAS has been tested across a wide range of studies and consistently showed a very high internal reliability (α = 0.87–0.94)[28,29]. Several Indian studies have utilized this scale to assess anxiety among children aged 11–16 years[4,7]. Reliability for the present study was established by test–retest method using Cronbach‘s α = 0.92 and split-half method using Pearson’s r (0.88).

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC): Depression was assessed with the CES-DC containing 20 items related to symptoms of depression. Higher scores indicate the severity of depression and a cut-off score of 15 suggests significant depression in children. Previous studies show good internal reliability (α = 0.86–0.87) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.85)[30,31]. The scale has been used in prior Indian studies to screen for depression among children[4,7]. Reliability for the present study was established by test–retest method (α = 0.93) and split-half method (α = 0.84).

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (KINEC: 12/15-16) and was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry-India (CTRI/2018/07/01499). Informed consent was obtained from the child and from at least one parent (who was the mother in all cases), before recruiting the participants. On completion of the 6-mo assessment, children in the waiting list control group were provided brief sessions of the CBT psychosocial intervention.

Data were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software package (version 28). The 2 test was used to examine the associations between group status (experimental vs control) with categorical measures, i.e., gender, type of family (nuclear/joint), domicile (urban/rural). For continuous measures (age, family income, anxiety, depression, self-esteem), the t test/Mann–Whitney U test was used. As the Shapiro Wilk’s test of normality indicated non-normal distribution of variables (anxiety, depression and self-esteem), the nonparametric Related-Samples Friedman’s Two-Way Analysis of Variance by Ranks was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the psychosocial intervention in terms of changes in the following outcomes (baseline vs 6 mo): (1) Self-esteem; (2) Anxiety; and (3) Depression. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Faculty from the Department of Biostatistics, NIMHANS, Bengaluru.

Participants’ baseline characteristics (n = 195) by group are presented in Table 2. Both groups were comparable on baseline parameters, except for monthly income of the family: Family income was significantly higher for participants in the control group, compared with the experimental group (Table 2). In all the participants, the father was the alcohol-consuming parent.

| Experimental group (n = 97) | Control group (n = 98) | P value1 | |

| Age in years | 14.73 (0.58) | 14.63 (0.58) | 0.23 |

| Gender | |||

| Male (%) | 66.0 | 55.0 | 0.12 |

| Female (%) | 34.0 | 45.0 | |

| Currently studying in | |||

| Standard 8 (%) | 42.0 | 46.0 | 0.60 |

| Standard 9 (%) | 58.0 | 54.0 | |

| Type of family | |||

| Nuclear (%) | 66.0 | 75.5 | 0.14 |

| Joint (%) | 34.0 | 24.5 | |

| Family monthly income (INR) | 9257.73 (3218.69) | 9918.37 (3051.69) | 0.04a |

| Duration of paternal alcohol dependence (in years) | 7.73 (3.21) | 7.31 (2.67) | 0.55 |

| Self-esteem | 20.05 (4.22) | 19.64 (3.73) | 0.49 |

| Anxiety | 34.65 (7.85) | 36.69 (9.36) | 0.18 |

| Depression | 13.30 (5.56) | 12.86 (5.34) | 0.54 |

Changes in outcome measures are presented in Table 3. The findings showed that, over the 6-mo follow-up period, participants in the experimental group (vs the control group) reported significantly higher self-esteem, lower anxiety and depression levels (P = 0.001). Further details, including the results of post hoc analyses, are presented in Table 3.

| Outcomes | Groups | Assessments, baseline | 1 mo | 3 mo | 6 mo | % of improvement | χ2 | P valuea | Significant pairs (posthoc) |

| Self-esteem | Experimental (n = 97) | 20 (16.50-23); 20.05 ± 4.22 | 22 (18.50-24.50); 21.67 ± 4.08 | 23 (20-26); 22.76 ± 4.28 | 25 (22-28); 24.98 ± 4.35 | 25 | 195.9 | 0.001 | Baseline-1 mo; Baseline-3 mo; Baseline-6 mo; 1-3 mo; 1-6 mo; 3-6 mo |

| Control (n = 98) | 19 (17-22); 19.64 ± 3.73 | 20 (17-22); 19.50 ± 3.67 | 20 (17-22); 19.50 ± 3.67 | 20 (17-22); 19.45 ± 4.03 | 5 | 24.43 | 0.001 | Baseline-6 mo; 1-6 mo; 3-6 mo; 3-1 mo; 3 mo-Baseline; 1 mo-Baseline | |

| Anxiety | Experimental (n = 97) | 36 (27-41); 34.65 ± 7.85 | 29 (24-39); 30.55 ± 7.50 | 25 (21-32); 26.81 ± 7.68 | 19 (15-26); 21.82 ± 8.57 | 47 | 237.3 | 0.001 | 6-3 mo; 6-1 mo; 6 mo-Baseline; 3-1 mo; 3 mo-Baseline; 1 mo-Baseline |

| Control (n = 98) | 35 (30-42.5); 36.69 ± 9.36 | 34.50 (29-45); 37.01 ± 10.33 | 31 (26-46); 35.13 ± 11.23 | 28.50 (22-45); 33.02 ± 12.43 | 19 | 31.9 | 0.001 | 6-3 mo; 6-1 mo; 6 mo-Baseline; 3-1 mo; 3 mo-Baseline; Baseline-1 mo | |

| Depression | Experimental (n = 97) | 13 (9.50-17); 13.30 ± 5.56 | 12 (9-15); 12.14 ± 5.03 | 9 (6-13); 10 ± 5.05 | 8 (4-10); 7.58 ± 4.71 | 38 | 243.5 | 0.001 | 6-3 mo; 6-1 mo; 6 mo-Baseline; 3-1 mo; 3 mo-Baseline; 1 mo-Baseline |

| Control (n = 98) | 12 (9-17); 12.86 ± 5.34 | 10 (7-16); 11.47 ± 5.44 | 10.50 (6-6.25); 11.19 ± 6.34 | 10 (6.75-18); 11.47 ± 6.55 | 17 | 48.9 | 0.001 | 6 mo-Baseline; 3-1 mo; 3 mo-Baseline; 1 mo-Baseline; 3-6 mo; 1-6 mo |

Children of alcohol-dependent parents are likely to suffer from various behavioral problems and are at risk for having higher internalizing behavioral problems. The present study evaluated the effectiveness of psychosocial intervention on reducing internalizing behavioral problems among children of alcohol-dependent parents at a school setting. In this study, the psychosocial intervention module was developed based on a CBT model. Prior empirical studies have shown that CBT, specifically brief-CBT delivering 8–10 sessions was effective in reducing anxiety and depression among children and adolescents[16,32,33]. In the present study, the psychosocial intervention module was developed keeping in mind local cultural sensitivities, and involved a comprehensive approach to the management of internalizing behavioral problems among children of alcohol-dependent parents.

The findings of the present study suggest that the experimental group showed a statistically significant decrease in anxiety and depression scores, and an increase in self-esteem scores (P < 0.001) over the 6-mo interval, indicating that the psychosocial intervention had a positive impact on the children. These findings are supported by previous studies which showed similar outcomes[32-36]. In this context, a recent study by Haugland et al[37] found that school-based CBT delivered by a school nurse was effective in reducing the anxiety among adolescents[37].

In western countries, CBT is delivered by school, pediatric and psychiatric nurses[38-40]. However, in the Indian set-up, CBT is practiced mostly by psychotherapists and psychiatrists. The article written by Halder and Mahato[41] on challenges and gaps in practice of CBT for children in India reports that CBT is one of the cost-effective treatments with fewer side effects and no complications[41]. Despite its proven efficacy, CBT continues to be limited to a select group of the population, e.g., to those who are able to afford CBT sessions, or live in areas where there are qualified and experienced clinical psychologists/psychiatrists. In reality, most of the Indian population live in rural areas or in those areas where there is poor access or availability of health professionals who can deliver CBT or other specialized psychosocial interventions. Against this scenario, training nurses in CBT can go a long way in recognizing and intervening appropriately with regard to specific mental health concerns in vulnerable populations such as children of parents with alcohol dependence. Furthermore, nursing in India is seeking to expand its role beyond the traditional functions in the hospital set-up. Thus, the present study provides empirical evidence, strengthening the need for the expansion of nursing services to community institutions such as schools.

The need for health professionals to be trained in identifying and assessing children with paternal problem drinking has been highlighted by prior studies[42]. In this connection, the findings of the present study have important implications for nursing services in India. Firstly, the use of alcohol is continuing to rise, and nursing interventions should be made part of formal nursing education programs. This inclusion should enable nursing students to recognize the importance of extending their services to family members of the substance using individuals as well, in particular the children, who are often the worst hit. Secondly, nurse administrators should conduct regular in-service education on extended interventions for substance use disorders for practicing nurses, particularly in the community, so that it is possible to prevent or identify internalizing or other problems early in children. Thirdly, nurse administrators need to negotiate with policy makers to ensure that nurses are employed formally in schools across the country, so that children with vulnerabilities obtain the needed attention and interventions, or referrals, as relevant. Finally, the findings also highlight the need for nurses to provide needed psychoeducation to family members to recognize mental health issues in their children and seek help, when there is a heavy drinking person in the family.

The empirical results reported here in should be considered in the light of some limitations. The trial was limited to a small sample size, which can restrict the generalizability of the findings to the larger population. Also, due to practical constraints, the follow-up assessment was conducted up to only 6 mo after the intervention. As anxiety and depression are chronic conditions, it may be desirable to have longer follow-up periods, thus providing greater insight into the intervention outcomes. Future research can be conducted by developing intervention for both children and parents, as the present study focused only on children.

The present study demonstrated that psychosocial intervention was effective in reducing anxiety and depression among children of parents with alcohol dependence. It also showed that self-esteem improved significantly after intervention. The findings clearly show the higher rate of anxiety and depression among children of parents with alcohol dependence. It emphasizes the need for ongoing psychosocial intervention for these children. The results of present study pave the way for future research that could develop policy and nursing standards in order to promote nurse-led psychological interventions for this vulnerable group.

The harmful use of alcohol afflicts not only the individual but also the whole family. The literature suggests that adults’ drinking is associated with physical and psychological harms to children. Children of alcoholics are at higher risk for internalizing behavioral problems.

There are few studies focused on school-based intervention for internalizing behavioral problems of children of alcoholic parents in India. There is a need for population-specific psychosocial intervention to prevent complications in childhood.

To develop and evaluate the efficacy of psychosocial intervention for internalizing behavior problems among children of alcoholic parents.

A randomized controlled trial with a 2 × 4 factorial design was adopted with longitudinal measurement of outcomes for 6 mo. The psychosocial intervention was administered to the experimental group biweekly in eight sessions over 4 wk after the pre-interventional assessment. The data were collected pre-intervention and at 1, 3 and 6 mo after intervention. Screening tests (modified) were used to identify children of alcoholic parents and Paediatric Symptom Checklist: Youth Report for behavioral problems among children of alcoholics. The outcome variables were assessed using Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

The present study demonstrated that the psychosocial intervention was effective in reducing anxiety and depression among children of alcoholic parents. It also shows that self-esteem improved significantly after intervention.

The findings of this provided initial evidence for the effect of psychosocial intervention for children of alcoholics in India.

The intervention was focused only on children and there is a chance of relapse of these problems due to the family atmosphere, hence future research should include alcoholic parents.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ben Thabet J, Tunisia; Oei TP, Australia S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, Mishra AK, Khandelwal SK, Chadda RK. On behalf of the group of investigators for the national survey on extent and pattern of substance use in India. Magnitude of substance use in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. 2019. [cited 10 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.ndusindia.in/downloads/Magnitude_India_EXEUCTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf. |

| 2. | Esser MB, Rao GN, Gururaj G, Murthy P, Jayarajan D, Sethu L, Jernigan DH, Benegal V; Collaborators Group on Epidemiological Study of Patterns and Consequences of Alcohol Misuse in India. Physical abuse, psychological abuse and neglect: Evidence of alcohol-related harm to children in five states of India. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35:530-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mason WA, Patwardhan I, Smith GL, Chmelka MB, Savolainen J, January SA, Miettunen J, Järvelin MR. Cumulative contextual risk at birth and adolescent substance initiation: Peer mediation tests. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:291-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Omkarappa DB, Rentala S, Nattala P. Psychiatric nurse delivered group-cognitive-behavioral therapy for internalizing behavior problems among children of parents with alcohol use disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;34:259-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A. 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:972-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 684] [Cited by in RCA: 622] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:980-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4651] [Cited by in RCA: 3626] [Article Influence: 241.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Omkarappa DB, Rentala S. Anxiety, depression, self-esteem among children of alcoholic and nonalcoholic parents. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:604-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sugaparaneetharan A, Kattimani S, Rajkumar RP, Sarkar S, Mahadevan S. Externalizing behavior and impulsivity in the children of alcoholics: A case-control study. J Mental Health Hum Behav. 2016;21:112-116. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Omkarappa DB, Rentala S, Nattala P. Social competence among children of alcoholic and nonalcoholic parents. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jaisoorya TS, Beena KV, Ravi GS, Thennarasu K, Benegal V. Alcohol harm to adolescents from others' drinking: A study from Kerala, India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dorsey S, McLaughlin KA, Kerns SEU, Harrison JP, Lambert HK, Briggs EC, Revillion Cox J, Amaya-Jackson L. Evidence Base Update for Psychosocial Treatments for Children and Adolescents Exposed to Traumatic Events. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46:303-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Weersing VR, Jeffreys M, Do MT, Schwartz KT, Bolano C. Evidence Base Update of Psychosocial Treatments for Child and Adolescent Depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46:11-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Freeman J, Benito K, Herren J, Kemp J, Sung J, Georgiadis C, Arora A, Walther M, Garcia A. Evidence Base Update of Psychosocial Treatments for Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Evaluating, Improving, and Transporting What Works. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47:669-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Villabø MA, Narayanan M, Compton SN, Kendall PC, Neumer SP. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth anxiety: An effectiveness evaluation in community practice. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86:751-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Nardi B, Massei M, Arimatea E, Moltedo-Perfetti A. Effectiveness of group CBT in treating adolescents with depression symptoms: a critical review. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Oud M, de Winter L, Vermeulen-Smit E, Bodden D, Nauta M, Stone L, van den Heuvel M, Taher RA, de Graaf I, Kendall T, Engels R, Stikkelbroek Y. Effectiveness of CBT for children and adolescents with depression: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;57:33-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stjerneklar S, Hougaard E, McLellan LF, Thastum M. A randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of an internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy program for adolescents with anxiety disorders. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0222485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Caldwell DM, Davies SR, Hetrick SE, Palmer JC, Caro P, López-López JA, Gunnell D, Kidger J, Thomas J, French C, Stockings E, Campbell R, Welton NJ. School-based interventions to prevent anxiety and depression in children and young people: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:1011-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bodicherla KP, Shah K, Singh R, Arinze NC, Chaudhari G. School-Based Approaches to Prevent Depression in Adolescents. Cureus. 2021;13:e13443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Baltaq V, Pachyna A, Hall J. Global overview of school health services: Data from 102 countries. Heal Behav Policy Rev. 2015;2:268-228. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kocoglu D, Emiroglu ON. The Impact of Comprehensive School Nursing Services on Students' Academic Performance. J Caring Sci. 2017;6:5-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bohnenkemp JH, Stephan SH, Bobo N. Supporting student mental health: The role of the school nurse in coordinated school mental health care. Psy In Sch. 2015;52:714-27. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hodgins DC, Maticka-Tyndale E, el-Guebaly N, West M. The cast-6: development of a short-form of the Children of Alcoholics Screening Test. Addict Behav. 1993;18:337-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Murphy JM, Ichinose C, Hicks RC, Kingdon D, Crist-Whitzel J, Jordan P, Feldman G, Jellinek MS. Utility of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist as a psychosocial screen to meet the federal Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) standards: a pilot study. J Pediatr. 1996;129:864-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chaurasiya AR, Hari JA. Hindi adaptation of pediatric symptom checklist-youth version (PSC-Y). Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2019;15:69-84. |

| 26. | Muppidathi S, Boj J, Kunjithapatham M. Use of the pediatric symptom checklist to screen for behaviour problems in children. Int J Contemp Pediatrics. 2017;4:886. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Sherrilene C, Craig AV, Mann, William C. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale as a Measure of Self-Esteem Noninstitutionalized Elderly. Clinl Geront. 2007;31:77-93. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Olofsdotter S, Sonnby K, Vadlin S, Furmark T, Nilsson KW. Assessing Adolescent Anxiety in General Psychiatric Care: Diagnostic Accuracy of the Swedish Self-Report and Parent Versions of the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale. Assessment. 2016;23:744-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Essau CA, Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous X, Muñoz LC. Psychometric properties of the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS) in Cypriot children and adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2011;42:557-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Betancourt T, Scorza P, Meyers-Ohki S, Mushashi C, Kayiteshonga Y, Binagwaho A, Stulac S, Beardslee WR. Validating the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children in Rwanda. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:1284-1292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jiang L, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Li R, Wu H, Li C, Wu Y, Tao Q. The Reliability and Validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) for Chinese University Students. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rith-Najarian LR, Mesri B, Park AL, Sun M, Chavira DA, Chorpita BF. Durability of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Effects for Youth and Adolescents With Anxiety, Depression, or Traumatic Stress:A Meta-Analysis on Long-Term Follow-Ups. Behav Ther. 2019;50:225-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hyun MS, Nam KA, Kim MA. Randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral therapy for at-risk Korean male adolescents. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;24:202-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | March S, Spence SH, Donovan CL, Kenardy JA. Large-Scale Dissemination of Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Youth Anxiety: Feasibility and Acceptability Study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Urao Y, Yoshida M, Koshiba T, Sato Y, Ishikawa SI, Shimizu E. Effectiveness of a cognitive behavioural therapy-based anxiety prevention programme at an elementary school in Japan: a quasi-experimental study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Park KM, Park H. Effects of self-esteem improvement program on self-esteem and peer attachment in elementary school children with observed problematic behaviors. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2015;9:53-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Haugland BSM, Haaland ÅT, Baste V, Bjaastad JF, Hoffart A, Rapee RM, Raknes S, Himle JA, Husabø E, Wergeland GJ. Effectiveness of Brief and Standard School-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions for Adolescents With Anxiety: A Randomized Noninferiority Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:552-564.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kozlowski JL, Lusk P, Melnyk BM. Pediatric Nurse Practitioner Management of Child Anxiety in a Rural Primary Care Clinic With the Evidence-Based COPE Program. J Pediatr Health Care. 2015;29:274-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Mohamed S. Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Program on Anxiety and Self-Esteem among Secondary School Students. Am J Nurs Sci. 2017;6:193-201. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Muggeo MA, Stewart CE, Drake LK, Ginsburg GS. A School Nurse-Delivered Intervention for Anxious Children. Sch Ment Health. 2017;9:157-171. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Halder S, Mahato AK. Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Children and Adolescents: Challenges and Gaps in Practice. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41:279-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Nattala P, Murthy P, Weiss MG, Leung KS, Christopher R, V JS, S S. Experiences and reactions of adolescent offspring to their fathers' heavy drinking: A qualitative study from an urban metropolis in India. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2022;21:284-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |