Published online May 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4519

Peer-review started: August 2, 2021

First decision: September 28, 2021

Revised: October 9, 2021

Accepted: March 25, 2022

Article in press: March 25, 2022

Published online: May 16, 2022

Processing time: 284 Days and 0.3 Hours

Plexiform neurofibromas are extremely rarely found in the region of cauda equina and can pose a significant challenge in the diagnostic and management sense. To our knowledge, only 7 cases of cauda equina neurofibromatosis (CENF) have been reported up-to-date.

We describe a case of a 55-year-old man with a 10 years history of progressive lower extremities weakness and bladder dysfunction. Before presenting, patient was misdiagnosed with idiopathic polyneuropathy. Lumbar spine MRI revealed a tortuous tumorous masses in the cauda equina region, extending through the Th12-L4 vertebrae. The patient underwent Th12-L3 Laminectomy with dura

CENF should be kept in mind during the differential diagnostic work-up for polyneuropathies. Management with an extensive decompression, duraplasty and primary spinal fixation represents a rational approach to achieve a sustained symptomatic improvement and superior overall outcome.

Core Tip: Plexiform neurofibroma manifestation in the region of cauda equina is an exceptionally rare event, as only 7 cases were described in the literature up-to-date. We present the 8th such case with the follow-up period of 10 years. Diagnosis was delayed because patient was initially misdiagnosed with the idiopathic polyneuropathy. In order to minimize the necessity for additional interventions in the future, we would recommend to pursue an extensive decompression with duraplasty and primary spinal fixation as the initial management of choice. However, we would strongly suggest to abstain from tumor resection attempts as risk of neurological complications is high.

- Citation: Chomanskis Z, Juskys R, Cepkus S, Dulko J, Hendrixson V, Ruksenas O, Rocka S. Plexiform neurofibroma of the cauda equina with follow-up of 10 years: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(14): 4519-4527

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i14/4519.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4519

Neurofibromas are benign nerve sheath tumors formed by a combined proliferation of different histological elements of a peripheral nerve. Two types of neurofibromas have been described according to their extent of tissue involvement[1]. Localized form, which can grow on the skin or as a peripheral nerve lesion, is the most common type seen and represents about 90% of all neurofibromas. Localized neurofibromas have minimal malignant potential, in the majority of cases are sporadic, and present as a solitary mass, but individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) tend to develop multiple lesions distributed in a diffuse fashion throughout the neural and cutaneous tissues[2]. The second type is plexiform neurofibroma—these tumors grow within the bundles of nervous tissues such as trunks and plexuses. This morphological aspect of neurofibromas makes the surgery difficult and radical tumor excision without neurological compromise virtually impossible. Plexiform lesions are said to have about 10% life-time risk to transform into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor and is significantly more likely in NF-1 population[3,4].

The cauda equina region is an extremely uncommon location for plexiform neurofibromas. Only seven cases of plexiform neurofibromas of the cauda equina (CENF) have been reported in the literature up-to-date[5-11]. Here we present a case of cauda equina plexiform neurofibroma with a follow-up period of 10 years.

A 55-year-old Lithuanian man presented with a progressive weakness in his lower extremities, fasciculations, difficulty urinating, and sexual dysfunction.

Weakness and fasciculations started about 10 years ago and progressed insidiously. Difficulties in urinating and sexual dysfunction started a few years ago and were only revealed after careful history taking.

The patient was previously diagnosed with idiopathic sensorimotor polyneuropathy. There was no history of other comorbidities, surgeries, allergies, or use of medications.

Patient denied the history of smoking, alcohol or substance abuse. The family history was unremarkable.

During the initial examination, patient vitals were normal (temperature 36.6 °C, respiratory rate 13 times/min, heart rate 69 bpm, and blood pressure 124/81 mmHg). Patient was slightly overweight (body mass index 26 kg/m2). Neurological examination revealed an absence of deep tendon reflexes in the lower extremities with diminished muscle strength, calf muscles atrophy, and mild impairment in proprioceptive and vibratory sensation bilaterally. Further neurological and general examination was unrevealing.

Complete blood count, biochemical analysis (including electrolytes, hepatic/renal and inflammatory markers), and coagulation testing were all within the normal values.

An initial instrumental investigation with electroneurography showed sensorimotor axonopathy of the left leg, whereas electromyography demonstrated an ongoing chronic denervation/reinnervation pattern in the muscles of the both legs.

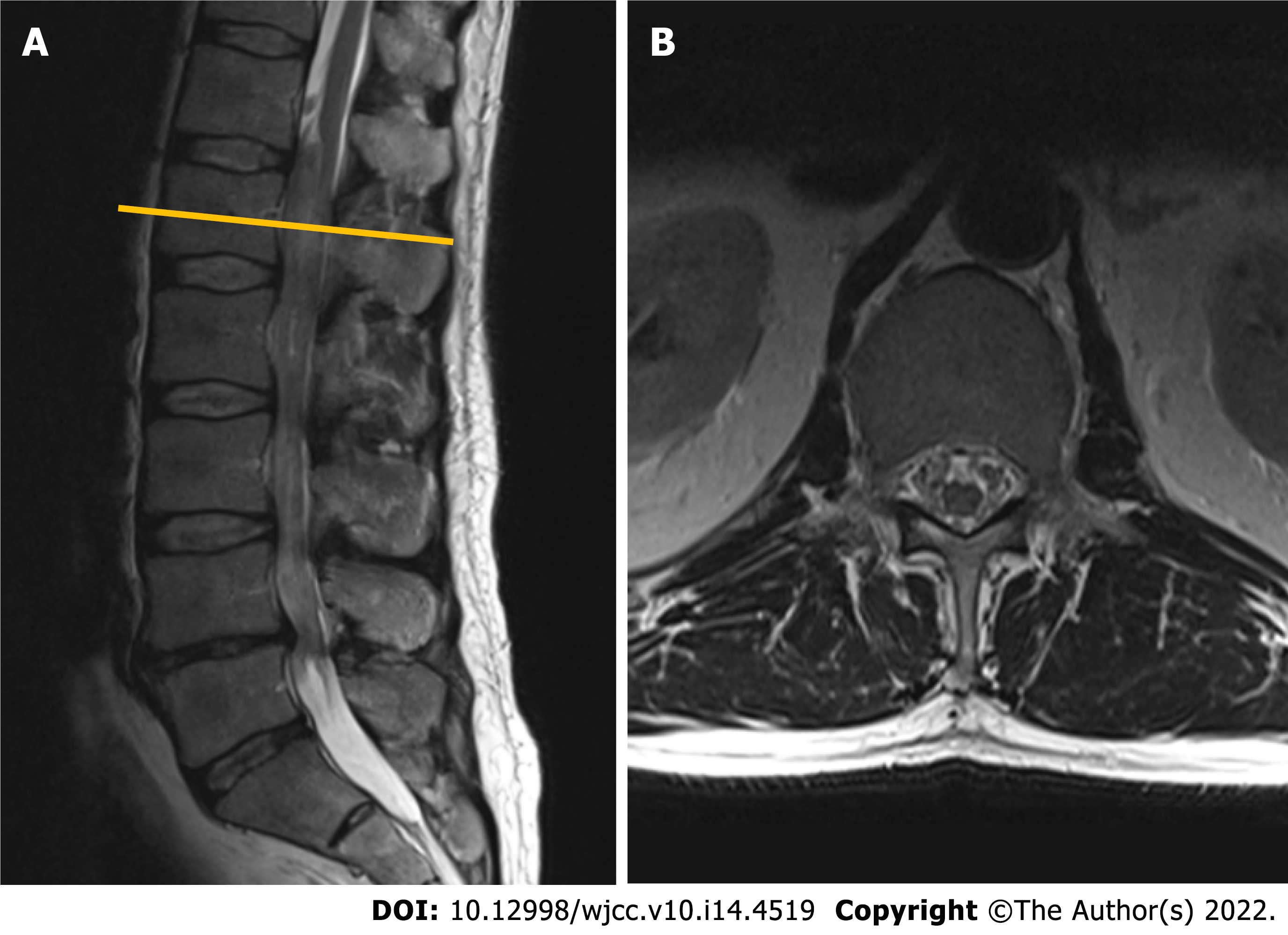

Given the long history of the disease with a progressive course and inconclusive neurophysiological study results, a gadolinium-enhanced lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. Imaging modality revealed a non-enhancing intradural tumor stretching out through the levels of Th12-L4 vertebrae. Diffusely enlarged, tortuous cauda equina roots were squeezed inside congenitally narrow spinal canal (Figure 1).

The final diagnosis of the presented case is plexiform neurofibroma of cauda equina. It was proven after the histopathological examination following the surgical treatment.

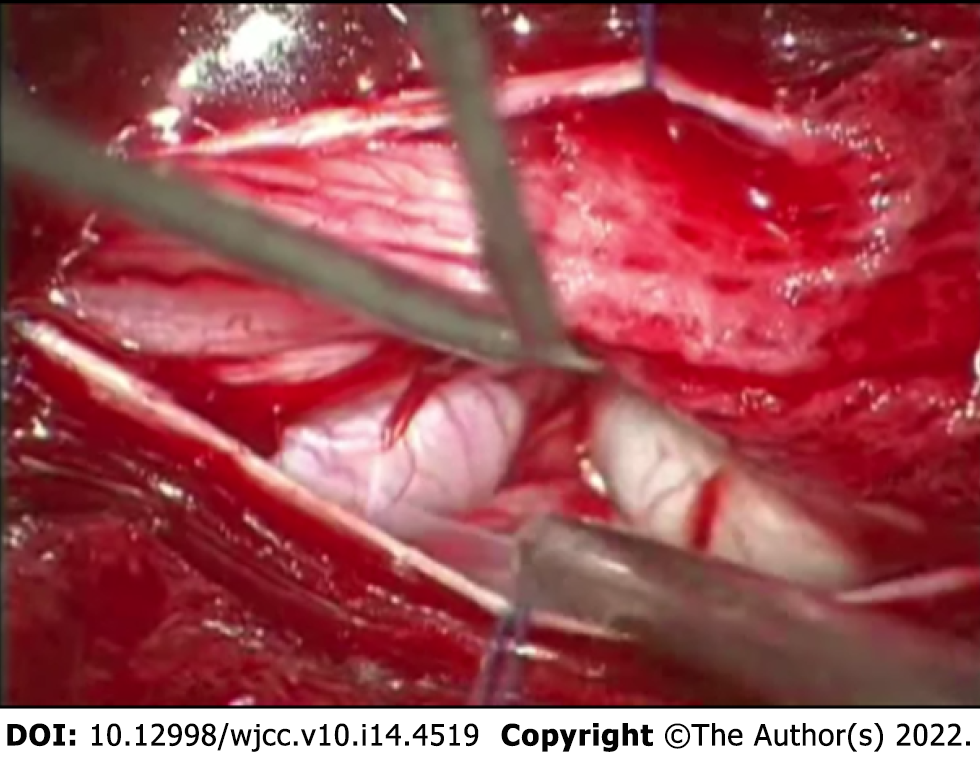

Given the likelihood of symptomatic progression and unclear pathological diagnosis, the surgical treatment was pursued – patient underwent Th12-L3 Laminectomy with duraplasty and biopsy of the lesion. During the operation, a few diffusely enlarged nerve roots were identified, with one nerve root being noticeably bulkier than the rest (Figure 2). The remaining nerve roots and conus medullaris were dislocated to the right. After careful intraoperative neuromonitoring, the decision to resect the most enlarged nerve root was made. The following surgical intervention was limited to the separation of adhesions between damaged roots and subsequent duraplasty with fascia lata graft.

Following the surgery, a slight improvement in sensorimotor function was concealed by development of permanent urinary retention. The histopathological study of biopsy material revealed a hypocellular tumor consisting of Schwann cells with wavy contours and elongated nuclei with fine dense chromatin, fibroblasts, and mast cells, a diagnosis consistent with plexiform neurofibroma (Figure 3). No deletions, duplications and translocations of NF1 gene were detected during fluorescence in situ hybridization (using specific markers for 17q11.2 area). Subsequent molecular genetic testing methods showed no point mutations characteristic for NF-1 or NF-2.

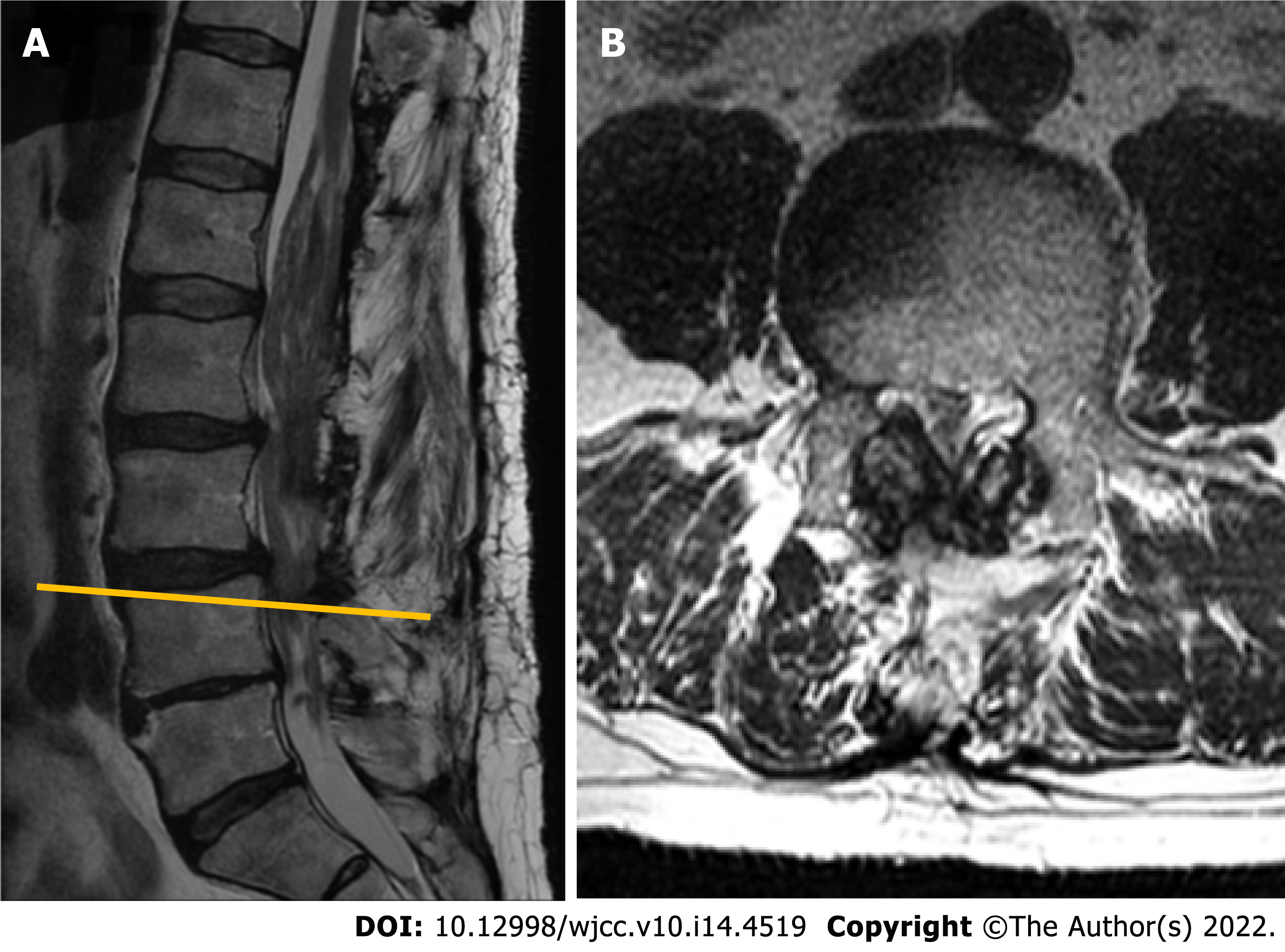

During the follow-up visit 5 years later, the patient reported that he had to intermittently catheterize himself 3-4 times a day and is experiencing some problems with ambulation, faring slightly worse than shortly after the decompression. Subsequent MRI revealed a slowly growing tumorous masses at the region of cauda equina (Figure 4). No compression was noted in the conus region due to extensive duraplasty, and there were no radiological signs of malignant transformation observed.

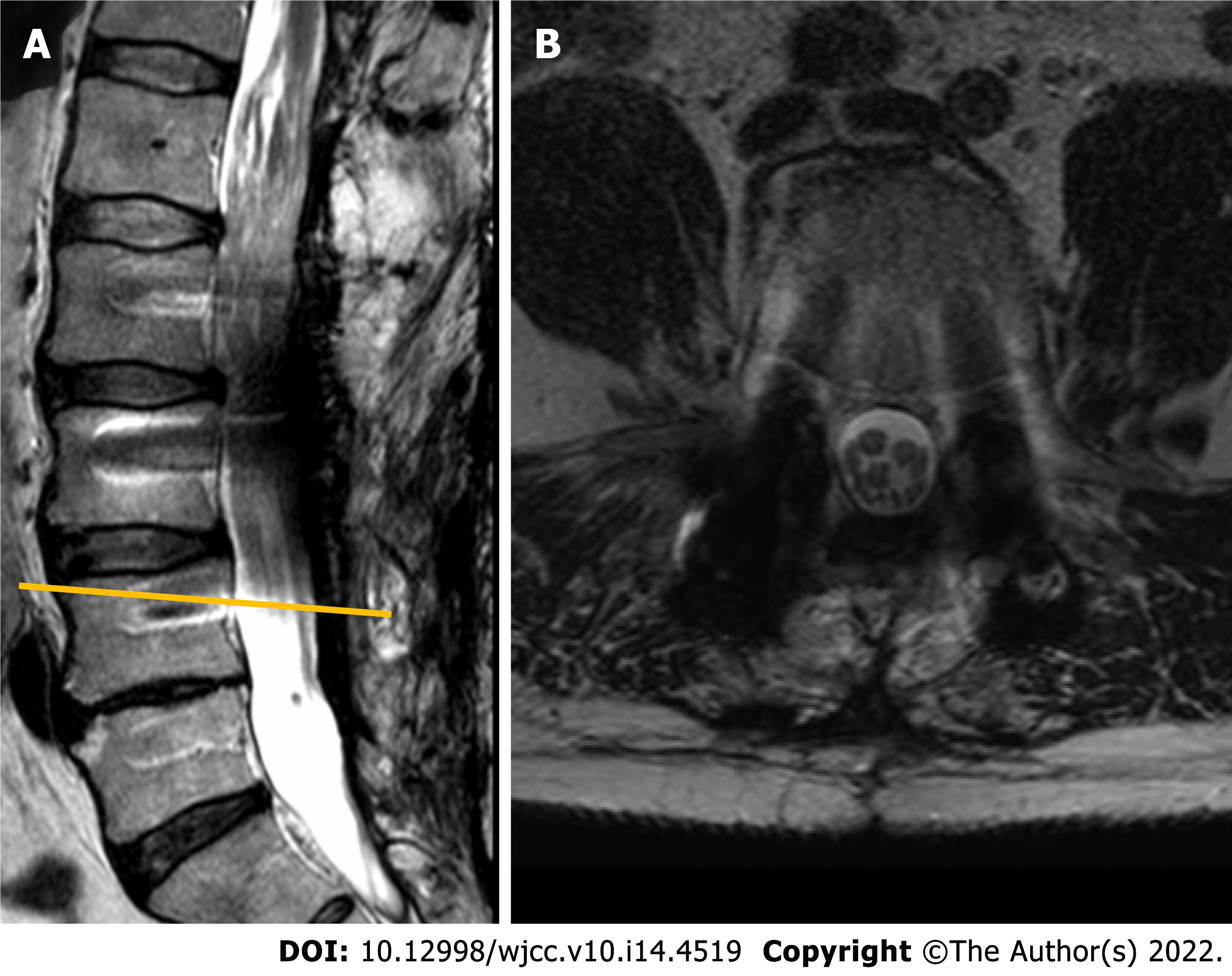

About 3 years later, the patient presented again for the follow-up with complaints of a significant worsening in motor function and pain in lower back which sometimes radiates to lower extremities, especially during physical activity. Neurological examination was significant for neurogenic claudication with a claudicating distance of 50 meters. Consequent MRI revealed a markedly enlarged tumorous masses occupying the majority of the vertebral canal with a central canal stenosis at L3-4 Level, mainly due to hypertrophy of facet joints and ligamenta flava (Figure 5).

Given the marked progression of symptoms and a radiological evidence of segmental stenosis, an operative treatment was proposed for the patient. Initially, patient decided to delay the intervention and wait, but neurological condition continued to worsen and 2 mo later he agreed to comply with the surgical management option. Patient underwent a L4-L5 Laminectomy with a caudal extension of previous duraplasty and L2-L5 transpedicular fixation (Figure 6). Hypertrophied ligamenta flava, facet joints, and visible adhesions were maximally removed from the spinal canal to accommodate the thecal sac. The post-operative period was uneventful, and patient’s pre-operative symptoms in terms of ambulation and pain improved dramatically following the operation. However, the problem of urinary retention remained unaffected, without the significant changes observed between the pre-operative and post-operative status.

During the most recent follow-up 18 mo after the second operation, the patient reported an improved quality of life, minor pain in the projection of lumbar spine, and persistence of minor lower extremities weakness with a similar degree of urinary dysfunction as prior the operation.

Plexiform neurofibromas of the cauda equina region are extremely rare tumors. To our knowledge, only seven cases have been reported to the date[5-11]. The main clinical features of previous cases are summarized in the table (Table 1). These tumors originate from various cellular elements comprising the nerve roots (i.e., axons, fibroblasts, Schwann cells)[5]. About 10% of plexiform neurofibromas eventually become malignant, and lesions in locations other than cauda equina are typically associated with NF-1[2,4]. Only in one case of CENF a diagnosis of NF was made, but surprisingly NF-2 was the genetic syndrome reported[8]. Our case demonstrated no association with NF.

| Patient | Localization | Complaints | Medical history | Treatment and outcome |

| 44-year-old male[5] | L3–L4 | Exacerbation of chronic lower back pain and bilateral leg pain | None of the stigmata of neurofibromatosis | Surgical treatment: laminectomy, resection of the tumor |

| 59-year-old male[6] | N/A | Progressive weakness in the lower limbs that began in infancy | Long-term follow-up presenting as peroneal muscle atrophy. His parents were first cousins | Died before the surgery because of respiratory insufficiency. Presence of ectopic motor neurons |

| 65-year-old male[7] | L3–L4 | Continuous severe lower back pain radiating into both L5 segments for several months | Suffered 20 years from pain and hypesthesia in the lumbar region and both legs. Slowly progressive atrophy of the crural muscles for 10 years | Surgical treatment: complete laminectomy of L3 through L4. Complete recovery from pain and gradual improvement in neurological signs |

| 20-year-old male[8] | L1–5, S1–3 | Right-sided foot drop, gait abnormality, bladder dysfunction | NF-2 positive, bilateral schwannomas, peripheral nerve involvement | Surgical treatment |

| 28-year-old male[9] | L4–L5 | Low back pain and bilateral radicular pain of lower extremities for the preceding 5 years | Unremarkable medical history. None of the stigmata of NF | Surgical treatment. Metaplastic ossification of the lesion. The patient was symptom-free within the first year after the surgery, when he again developed lower back pain |

| 56-year-old male[10] | L1–L2 | Urinary retention and saddle anesthesia | None of the stigmata of neurofibromatosis. After an episode of poliomyelitis at the age of 10 had muscle atrophy, severe motor disturbance, and mild sensory disturbance of the left leg | After surgery returned to his previous condition |

| 4-year-old boy[11] | L3- sacrum | 8-month history of severe lower back pain that radiated bilaterally into the L4–5 distribution. The results of a neurological examination were normal | No family history of NF. Incidental thoracic-level dermal sinus | Surgical treatment: spinous processes and laminae were exposed from L2 to L5, en bloc laminectomy and laminoplasty. The dissection of the tumor was abandoned to avoid neurological compromise. After the operation, the patient still experienced significant pain, so radiotherapy was administered to control the tumour and relieve his pain |

Previously published cases showed various combinations of progressive symptoms, the most common being the lumbar and lower extremities pain for prolonged periods of time before a clinical condition worsened and advanced to polyneuropathy. Although the probability of neoplastic process in such patients remains low, we would advocate for a more comprehensive investigation in a form of neuroimaging, especially if patient reports a prolonged history of gradually worsening complaints. Given the complex differential diagnosis process surrounding polyneuropathies, a low threshold for radiological assessment would minimize the likelihood of delayed diagnosis and treatment not only in cases of CENF, but also other slowly growing lesions.

The topic regarding an optimal management strategy and the extent of the surgery remains somewhat controversial, as various operative options could be supported by reasonable arguments. On the more conservative end of the spectrum, the practice of open biopsy together with targeted decompression and duraplasty could be sufficient in selected cases. Anyway, we decided to pursue a complete resection of the most enlarged neural root due to the fact that intraoperative monitoring showed it as silent and achieving adequate decompression was highly unlikely without the removal of the mass. The combination of Th12-L3 Laminectomy and duraplasty together with a resection of prevailing pathological nerve root allowed us to attain a satisfactory degree of decompression, but this came at the expense of permanent urinary retention as a complication. However, lack of primary spinal fixation resulted in some degree of post-operative instability one segment below the most caudal laminectomy site. Over the prolonged period of time (in our case 8 years), this facilitated the evolution of compensatory hypertrophy of facet joints and ligamenta flava, culminating in the spinal canal stenosis at L3-L4 Level. Combination of instability-induced stenosis and slowly but steadily growing CENF creates a recipe for disaster and will eventually result in the demand for an additional neurosurgical input. Therefore, we would recommend leaning right towards the more aggressive pole in terms of operative management – performing wide posterior decompression, adequate duraplasty, and primary spinal fixation in our opinion poses the best possibility to yield sustained symptomatic relief in the long-term and will likely decrease the necessity for additional interventions in the future. However, the sacrifice of neural elements should be discouraged regardless of intra-operatively recorded evoked potentials data, as the risk of complications will likely exceed potential benefits.

Redundant nerve root syndrome is another perplexing condition which requires pathological assessment in order to differentiate from CENF. The syndrome has analogous clinical and radiological picture as it manifests with thickened, large, tortuous, and elongated nerve roots in the area of cauda equina. Although it is believed that mechanical trapping at the level of lumbar spinal stenosis is the mechanism of pathogenesis, the clinical relevance of the syndrome remains a matter of debate[12,13]. Some authors suggest that at least a part of the previously described cases of redundant nerve root syndrome could actually be misdiagnosed plexiform neurofibromas and vice versa[14]. Given the similar clinical, radiological, and gross visual appearance, emphasis should be placed on the importance of histopathological evaluation in every case of suspected redundant nerve root syndrome, as at least part of these lesions could turn out neoplastic in origin.

Cauda equina is an extremely rare location for plexiform neurofibromas to manifest. This case report illustrates complicated diagnostic process as clinical presentation may mimic other polyneuropathies, and challenges associated with management of such individuals. We would strongly recommend a generous posterior decompression with duraplasty and primary spinal fixation in order to achieve the optimal long-term results. Tumor resection, even in the electroneurographically silent roots, should be discouraged.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Lithuania

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ma X, China; Munakomi S, Nepal S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chang KL

| 1. | Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10993] [Cited by in RCA: 10867] [Article Influence: 1207.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:834-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Prada CE, Rangwala FA, Martin LJ, Lovell AM, Saal HM, Schorry EK, Hopkin RJ. Pediatric plexiform neurofibromas: impact on morbidity and mortality in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr. 2012;160:461-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nguyen R, Dombi E, Akshintala S, Baldwin A, Widemann BC. Characterization of spinal findings in children and adults with neurofibromatosis type 1 enrolled in a natural history study using magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurooncol. 2015;121:209-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Joseffer SS, Babu RP, Kleinman G. Plexiform neurofibroma of the cauda equina: case report. Surg Neurol. 2005;63:182-4; discussion 184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Berciano J, Figols J, Combarros O, Calleja J, Pascual J, Oterino A. Plexiform neurofibroma of the cauda equina presenting as peroneal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:250-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schumacher M, Gilsbach J, Friedrich H, Mennel HD. Plexiform neurofibroma (Rankenneurofibrom) of the cauda equina. Neuroradiology. 1978;15:221-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kara M, Akyüz M, Yılmaz A, Hatipoğlu C, Ozçakar L. Peripheral nerve involvement in a neurofibromatosis type 2 patient with plexiform neurofibroma of the cauda equina: a sonographic vignette. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:1511-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Azarpira N, Derakhshan N, Esfahani MH. Plexiform Neurofibroma of the Cauda Equina With Ectopic Bone Formation. Neurosurg Q. 2015;25:97-99. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Simou N, Zioga A, Zygouris A, Pahatouridis D, Charalabopoulos K, Batistatou A. Plexiform neurofibroma of the cauda equina: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2008;16:78-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nadkarni TD, Rekate HL, Coons SW. Plexiform neurofibroma of the cauda equina. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:112-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Poureisa M, Daghighi MH, Eftekhari P, Bookani KR, Fouladi DF. Redundant nerve roots of the cauda equina in lumbar spinal canal stenosis, an MR study on 500 cases. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:2315-2320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nogueira-Barbosa MH, Savarese LG, Herrero CFP da S, et al. Redundant nerve roots of the cauda equina: review of the literature. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:155-159. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hakan T, Celikoğlu E, Aydoseli A, Demir K. The redundant nerve root syndrome of the Cauda equina. Turk Neurosurg. 2008;18:204-206. [PubMed] |