Published online May 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4395

Peer-review started: July 16, 2021

First decision: October 18, 2021

Revised: October 26, 2021

Accepted: March 25, 2022

Article in press: March 25, 2022

Published online: May 16, 2022

Processing time: 300 Days and 19.1 Hours

Depression has been reported to be prevalent in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB). Moreover, several clinical symptoms of PTB and depression overlap, such as loss of appetite and malnutrition. However, the association between depression and malnutrition in TB patients has not been fully elucidated.

To explore the association between depression and malnutrition in patients with PTB.

This hospital-based cross-sectional study included patients with PTB in Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital Affiliated to Tongji University from April 2019 to July 2019. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scale was used to evaluate depre-ssion. The cut-off value was set at 10, and the nutritional state was determined by the body mass index (BMI). In addition, the Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases was employed to establish the quality of life (QOL). Univariable analysis and multivariable analysis (forward mode) were implemented to identify the independent factors associated with depression.

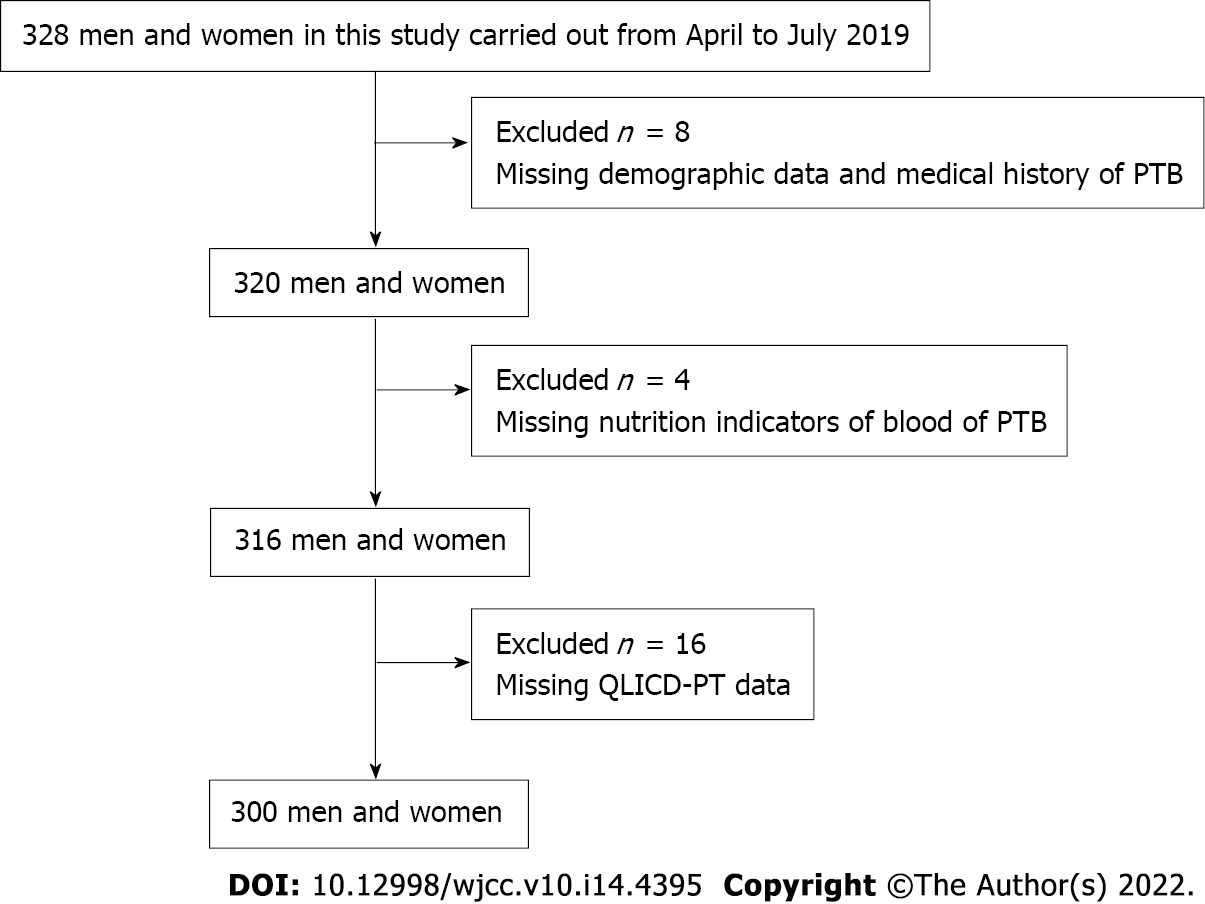

A total of 328 PTB patients were screened for analysis. Eight were excluded for missing demographic data, four excluded for missing nutrition status, and sixteen for missing QOL data. Finally, 300 PTB patients were subjected to analysis. We found that depressive state was present in 225 PTB patients (75%). The ratio of malnutrition in the depressive PTB patients was 45.33%. Our results revealed significantly lower BMI, hemoglobin, and prealbumin in the depression group than in the control group (P < 0.05). Moreover, the social status differed significantly (P < 0.05) between the groups. In addition, glutamic pyruvic transaminase and glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase in the depression group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P < 0.05). Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that BMI [odds ratio (OR) = 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.163-1.257, P < 0.001] and poor social function (OR = 0.95, 95%CI: 0.926-0.974, P = 0.038) were independently associated with depression.

Malnutrition and poor social function are significantly associated with depressive symptoms in PTB patients. A prospective large-scale study is needed to confirm these findings.

Core Tip: In this hospital-based cross-sectional study, the data of 300 pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) patients were subjected to analysis. The ratio of malnutrition in tuberculosis-depression syndemic patients was 45.33%. We found that body mass index and poor social function were independently associated with depression. Our present findings suggest that the early diagnosis and management of depression in patients with PTB can decrease the burden of malnutrition and improve outcomes.

- Citation: Fang XE, Chen DP, Tang LL, Mao YJ. Association between depression and malnutrition in pulmonary tuberculosis patients: A cross-sectional study. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(14): 4395-4403

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i14/4395.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4395

Pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), a chronic wasting disease, is a chronic pulmonary infection which is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. An estimated 9.0-11.1 million PTB cases were diagnosed in 2018 worldwide, 1.0 million of which were children[1]. PTB presents as a global public health problem, and the situation in developing countries, including China, is even worse. Despite the decreasing trend of PTB prevalence in China, PTB remains a considerable threat to public health due to the high number of PTB patients and the multidrug-resistant PTB burden[2]. Cumulative evidence revealed that depression was prevalent in people with chronic diseases[3]. In addition, the ratio of PTB patients with depression was higher than that in healthy populations[4]. In a hospital-based cross-sectional study conducted in Cameroon, Kehbila et al[5] found that more than 50% of PTB patients were affected by depression. In Manila, the Philippines, approximately 16.8% of the PTB patients reportedly had depression[6]. However, no hospital-based study has been published on the prevalence of this state in patients with PTB in China. Previous reports have evidenced that human immune deficiency virus infection, poor social support, and perceived stigma are risk factors for the development of depression in PTB patients[7-9]. Moreover, the depression in patients with PTB is associated with insufficient health care and poor treatment compliance, which has led to drug resistance, morbidity, and mortality[10], negatively affecting the health-related quality of life (QOL) of PTB patients[11,12]. Additionally, PTB patients were susceptible to malnutrition, with a ratio of malnutrition from 38.3% to 75.0%[13]. Furthermore, malnutrition also triggered PTB relapse and increased mortality[14,15]. Appropriate and timely intervention for malnutritional and/or depressed PTB patients is a medical need. We hypothesized that depression may be prevalent in malnutritional PTB patients in China. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to evaluate the association between depression and malnutrition in PTB patients in China.

This is a hospital-based cross-sectional study, which was conducted from April to July 2019 in Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital Affiliated to Tongji University, China. Patients with PTB were consecutively recruited for analysis. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Clear consciousness; (2) Ability to communicate; (3) Patients who have provided informed consent and voluntarily participated in this study; and (4) Age above 18 years. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) A history of mental illness; (2) Complications, such as disturbance of consciousness, chronic respiratory failure, and pulmonary encephalopathy; (3) Metabolic-related diseases such as thyroid disease; (4) Requirements for continuous non-invasive or invasive ventilation; (5) Unstable hemodynamics; (6) Cardiac or renal insufficiency; and (7) Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. All subjects provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee (No. K19-146).

Data including age, educational level, occupation, marital status, body mass index (BMI), income, comorbidity, treatment duration, hemoglobin (Hb), albumin, liver function [alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)], and medical cost origin were collected by nurses (Fang XE, Chen DP, and Tang LL) who received uniform training by face-to-face interviews. On post-admission day, the patient’s height and weight were measured. The height was measured using a calibrated ruler (± 0.5 cm); the actual body weight was measured using a corrected scale (± 0.2 kg). BMI was calculated as [weight (kg)/height (m2)]. Next, BMI was used to assess the nutritional status[16] (Supplementary Table 1), and BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2 was considered to represent malnutrition[17].

Depression was evaluated by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)[18], which consists of nine questions and has been validated in China with a Cronbach’s alpha value higher than 0.8. Each item was scored as 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half of the days), or 3 (nearly every day); the total score ranged from 0 to 27. A PHQ-9 value higher than 10 showed a higher susceptibility to depression[19]. Hence, the included PTB patients were divided into two groups: Depression and control, based on a PHQ-9 threshold of 10.

The level of QOL was assessed by the Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases-Pulmonary Tuberculosis (QLICD-PT)[20], which has been validated in China with a Cronbach’s alpha value higher than 0.7. The QLICD-PT includes three domains and a specific model: Physiological function (basic physiological function, independence, energy, and discomfort), psychological function (cognition, emotion, will, and personality), social function (interpersonal interaction, social support, and social role), and specific module (respiratory symptoms, systemic symptoms, drug side effects, and special psychology).

The sample size for this study was calculated using the formula: n = (z)2p(1-p)/e2, where z is 1.96 [the value at 95% confidence interval (CI)], e is the standard error (estimated at 1/8), and p is the ratio of depression. We estimated that 50% of the PTB patients would develop depression. Considering a potential 20% loss, we established that at least 300 PTB patients for inclusion were required.

SPSS software (version 20.0 Chicago, IL, United States) was used to analyze the data. Continuous data are presented as the mean ± SD. Normality distribution was determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Student’s independent t-test or Mann-Whitney test was used depending on the normality. Categorical data are expressed as numbers (percentages) and were analyzed using the c2 test. Univariable analysis was applied to identify the independent factors which are associated with depression. To identify potential confounders, factors with P < 0.1 in the univariable analysis were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model and were assessed using the forward mode. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

A total of 328 PTB patients were recruited. Of them, we excluded eight for missing data, four for missing nutrition indicators of blood, and sixteen for missing QLICD-PT scale data. Finally, 300 PTB patients (91.46%) were subjected to analysis (Figure 1). The mean age of the respondents was 35.96 (± 13.17; range 21-40, median 30) years. Of the patients included, 189 (63%) were men, 180 (60%) were married, 93 (31%) had undergraduate education, and 170 (56.67%) were unemployed (Table 1).

| Variable | |

| Age, yr | 35.96 ± 13.17 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 189 (63.00%) |

| Female | 111 (37.00%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 180 (60.00%) |

| Unmarried | 115 (38.30%) |

| Divorced/separated | 5 (1.70%) |

| Education | |

| Junior primary | 153 (51.00%) |

| Senior primary secondary and above | 147 (49.00%) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 170 (56.67%) |

| Employed | 130 (43.33%) |

| Monthly income, Yuan | |

| < 5000 | 159 (53.00%) |

| 5000-10000 | 121 (40.30%) |

| > 10000 | 20 (6.70%) |

| TB treatment duration | |

| < 6 mo | 144 (48.00%) |

| 6-12 mo | 49 (16.30%) |

| > 12 mo | 107 (35.70%) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (3.70%) |

| Source of medical costs | |

| Medical insurance | 203 (67.60%) |

| Self-supporting | 66 (22.00%) |

| Publicly-funded | 31 (10.30%) |

| BMI | 19.71 ± 2.94 |

| Hb (g/L) | 122.21 ± 22.88 |

| ALB (g/L) | 40.25 ± 11.61 |

| Prealbumin | 200.13 ± 75.46 |

| PHQ-9 | 16.45 ± 5.35 |

| AST (U/L) | 25.66 ± 52.64 |

| ALT (U/L) | 26.12 ± 52.16 |

| QLICD-PT | |

| Physical domain | 22.46 ± 3.90 |

| Psychological domain | 22.89 ± 8.13 |

| Social domain | 23.21 ± 6.50 |

| Specific domain | 39.38 ± 8.00 |

Based on the PHQ-9 score at 10, the PTB patients were divided to depression (n = 225, 75%) and control (n = 75, 25%) groups. The ratio of malnutrition among depressive status with PTB patients was 45.33% (Table 2). No statistically significant differences were detected between the groups in age, gender, marital status, education level, occupation, monthly income, TB treatment duration, comorbidity, or origin of medical costs (P > 0.05). The values of BMI (P < 0.001), Hb (P < 0.05), prealbumin (P < 0.05), and social function of QLICD-PT (P < 0.05) in the depression group were significantly lower than those in the control group. In addition, AST and ALT in the depression group were significantly higher than those in the control group (Table 2). Finally, logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the possible factors that influence depression. As can be seen in Table 3, BMI [odds ratio (OR) = 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.163-1.257, P < 0.001] and poor social function (OR = 0.95, 95%CI: 0.926-0.974, P = 0.038) were independently associated with depression.

| Depression status | P value | ||

| PHQ 10 (n = 225) | PHQ < 10 (n = 75) | ||

| Age, yr | 36.20 ± 13.32 | 35.27 ± 12.27 | 0.598 |

| Gender | 0.371 | ||

| Male | 146 (64.40%) | 44 (58.70%) | |

| Female | 36 (80.00%) | 31 (41.30%) | |

| Marital status | 0.555 | ||

| Married | 134 (59.60%) | 46 (61.30%) | |

| Single co-habiting | 88 (39.10%) | 27 (36.00%) | |

| Divorced/separated | 3 (1.30%) | 2 (2.70%) | |

| Educational level | 0.809 | ||

| Junior primary | 114 (51.10%) | 38 (50.67%) | |

| Senior primary, secondary, and above | 111 (48.90%) | 37 (49.33%) | |

| Occupation | 0.998 | ||

| Unemployed | 123 (54.67%) | 47 (61.84%) | |

| Employed | 102 (45.33%) | 28 (37.33%) | |

| Monthly income, Yuan | 0.302 | ||

| < 5000 | 123 (54.70%) | 36 (48.00%) | |

| 5000-10000 | 88 (39.10%) | 33 (44.00%) | |

| > 10000 | 14 (6.20%) | 6 (8.00%) | |

| TB treatment duration | 0.559 | ||

| < 6 mo | 105 (46.70%) | 39 (52.00%) | |

| 6-12 mo | 39 (17.30%) | 10 (13.30%) | |

| > 12 mo | 81 (36.00%) | 26 (34.70%) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (3.10%) | 4 (5.33%) | 0.376 |

| Hemoptysis | 29 (12.90%) | 6 (7.80%) | 0.254 |

| Source of medical costs | 0.503 | ||

| Medical insurance | 153 (68.00%) | 50 (66.67%) | |

| Self-supporting | 53 (23.60%) | 13 (17.33) | |

| Publicly-funded | 19 (8.40%) | 12 (16.00%) | |

| Nutrition related indicators | |||

| BMI | 19.26 ± 2.63 | 21.22 ± 3.45 | < 0.001a |

| Hb (g/L) | 120.21 ± 24.37 | 128.79 ± 16.12 | 0.004a |

| ALB (g/L) | 40.81 ± 13.10 | 38.59 ± 4.60 | 0.254 |

| Prealbumin | 176.10 ± 2.68 | 210.96 ± 63.17 | 0.001a |

| QLICD-PT | |||

| Physical function | 27.27 ± 53.00 | 8.04 ± 1.28 | 0.331 |

| Psychological function | 30.18 ± 8.55 | 23.01 ± 4.83 | 0.173 |

| Social function | 23.21 ± 6.66 | 29.01 ± 6.68 | 0.004a |

| Specific function | 40.03 ± 7.93 | 23.21 ± 6.00 | 0.562 |

| Liver function | |||

| ALT (U/L) | 37.77 ± 40.92 | 34.04 ± 90.36 | 0.036a |

| AST (U/L) | 37.84 ± 38.41 | 33.25 ± 94.75 | 0.014a |

| Variable | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| BMI | 1.21 | 1.163-1.257 | < 0.001 |

| Social function | 0.95 | 0.926-0.974 | 0.038 |

| Hb | 0.99 | 0.982-1.012 | 0.67 |

| Prealbumin | 1.00 | 0.998-1.002 | 0.65 |

| Psychological function | 0.99 | 0.958-1.043 | 0.97 |

| ALT | 1.00 | 0.978-1.025 | 0.93 |

| AST | 0.99 | 0.967-1.025 | 0.75 |

The assessment of the depressive state in patients with PTB using the PHQ-9 scale showed that 75% of the study subjects developed depression. In addition, the results of the present study also suggest that nutritional status and social function were independent risk factors for depression. In clinical practice, nutrition management and psychological counseling for PTB patients are highly necessary.

The prevalence of depression in the PTB patients included in the present study was estimated to be higher than that determined in other studies; for example, it was 41.1% in Nigeria[21], 61.1% in Cameron[5], 56% in Pakistan[22], 54% in Ethiopia[23], and 69.6% in Liaoning Province of China[3]. In other investigations, the comorbidity of mental disorders in hospitalized patients ranged from 19%[24] to 80%[25]. In a study performed in the Philippines, the depressive state among PTB patients was 16.8%[6]. These findings suggest that the depressive state in PTB patients varies and is country-specific. In the present study, the depression ratio was 75%, which was higher than those in most of the published reports. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the sample size, race, country-specific features, patient populations (hospitalized or not), and the specific depression assessment tool implemented.

Here, we found that the ratio of malnutrition among depressive PTB patients was 45.33%. Patients with non-depression status had higher levels of BMI, Hb, and prealbumin than patients with depression. Furthermore, the ratio of anemia among depressive PTB patients was 86.32%, which may due to the effect of TB on red blood cell production, such as decreased erythrocyte lifespan, poor erythrocyte iron incorporation, and decreased sensitivity to erythropoietin[16]. Masumoto et al[6] also recommended that additional attention should be paid to malnourished PTB patients and those with poor social support to identify depression. Therefore, nutritional support for PTB patients may be necessary.

Nutrition problems may be caused by mental health issues, and thus the symptoms of malnutrition and psychological distress may overlap[26]. In this study, we found an association between malnutrition and depression, in which the following factors might be involved or causative: (1) Depression may lead to loss of appetite and digestive dysfunction; (2) Continuous mental stimulation leads to serious vegetative nerve dysfunction and endocrine imbalance, which affects the body’s absorption of nutrients; and (3) The disease itself can increase catabolism, promoting protein decomposition and reducing protein synthesis. In addition, a negative association between depression and poor social function may exist. There may be a vicious circle, including malnutrition, QOL, and depression. Malnutrition may aggravate depression and seriously affect the QOL, while the loss of appetite in depressed patients can lead to malnutrition.

This study is not without limitations. As it was hospital-based cross-sectional, the risk factors for depression in different treatment periods in patients with PTB could not be identified. Additionally, no additional validation of the depression and QOL scales was performed. Moreover, the nutritional status was evaluated by BMI, while many other indicators could also reflect the nutritional status. The energy intake was not assessed, which could have introduced bias. Furthermore, data of the severity of PTB were not collected. Socio-economic status was reported to be a confounding factor between nutritional status and depression[27]. However, we did not explore that association.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study suggest that depression is common in hospitalized PTB patients, and psychological counseling or management and nourishment adjustments may be needed. To confirm the findings of the present study, a well-designed prospective large-scale study is needed.

It has been reported that depression is prevalent in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB). Moreover, several clinical symptoms of PTB and depression overlap, such as loss of appetite and malnutrition. However, the association between depression and malnutrition in TB patients has not been fully understood.

The present study aimed to explore the association between depression and malnutrition in patients with PTB.

The present study aimed to explore the association between depression and malnutrition in patients with PTB.

This hospital-based cross-sectional study included patients with PTB in Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital Affiliated to Tongji University from April 2019 to July 2019. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scale was used to evaluate depression and the cut-off value was set at 10, and the nutritional state was determined by the body mass index (BMI). In addition, the Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases was employed to quantify the quality of life (QOL). Univariable analysis and multivariable analysis (forward mode) were used to identify the independent factors associated with depression.

A total of 328 PTB patients were screened for analysis. Eight were excluded for missing demographic data, four excluded for missing nutrition status, and sixteen for missing QOL data. Finally, 300 PTB patients were subjected to analysis. It was found that depressive state was present in 225 PTB patients (75%). The ratio of malnutrition in the depressive PTB patients was 45.33%. It was found that BMI, hemoglobin, and prealbumin in the depression group were significantly lower than those in the control group (P < 0.05). Moreover, the social status (P < 0.05) significantly differed between the groups. In addition, glutamic pyruvic transaminase and glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase in the depression group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P < 0.05). Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that BMI [odds ratio (OR) =1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.163-1.257, P < 0.001] and poor social function (OR = 0.95, 95%CI: 0.926-0.974, P = 0.038) were independently associated with depression.

Malnutrition and poor social function are significantly associated with depressive symptoms in PTB patients. A prospective large-scale study is needed to confirm these findings.

Malnutrition and poor social function are significantly associated with depressive symptoms in PTB patients. A prospective large-scale study is needed to confirm these findings.

The authors appreciate the respective study institution for their help and the study participants for their cooperation in providing all necessary information.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abdelbasset WK, Saudi Arabia S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2018. [cited 15 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565646. |

| 2. | Huang L, Li XX, Abe EM, Xu L, Ruan Y, Cao CL, Li SZ. Spatial-temporal analysis of pulmonary tuberculosis in the northeast of the Yunnan province, People's Republic of China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Contini B. Threats and organizational design. Behav Sci. 1967;12:453-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shen TC, Wang CY, Lin CL, Liao WC, Chen CH, Tu CY, Hsia TC, Shih CM, Hsu WH, Chung CJ. People with tuberculosis are associated with a subsequent risk of depression. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:936-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kehbila J, Ekabe CJ, Aminde LN, Noubiap JJ, Fon PN, Monekosso GL. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in adult patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in the Southwest Region of Cameroon. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Masumoto S, Yamamoto T, Ohkado A, Yoshimatsu S, Querri AG, Kamiya Y. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive state among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Manila, The Philippines. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:174-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Olden K, Hempfling WP. The 503-nm pigment of Escherichia coli B: characterization and nutritional conditions affecting its accumulation. J Bacteriol. 1973;113:914-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Naidoo P, Mwaba K. Helplessness, depression, and social support among people being treated for tuberculosis in south africa. Soc Behav Personal. 2010;38:1323-1333. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee LY, Tung HH, Chen SC, Fu CH. Perceived stigma and depression in initially diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis patients. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:4813-4821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gaze H. Ethics: a question of morality. Nurs Times. 1987;83:18-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Darby DW. The dentist and continuing education--attitudes and motivations. J Am Coll Dent. 1969;36:165-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Oppo GT, Segre A, Morelli L. [Changes in serum leucine aminopeptidase during pregnancy, delivery and puerperium]. Minerva Ginecol. 1969;21:881-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cammer L. Antidepressants as a prophylaxis against depression in the obsessive compulsive person. Psychosomatics. 1973;14:201-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kant S, Gupta H, Ahluwalia S. Significance of nutrition in pulmonary tuberculosis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55:955-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kumar A, Kakkar R, Kandpal S, Sindhwani G. Nutritional status in multi-drug resistance-pulmonary tuberculosis patients. IJCH. 2015;26:204-208. |

| 16. | Portal RW. Elective surgery after myocardial infarction. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;284:843-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | World Health Organization. Nutrition landscape information system (nlis) country profile indicators: Interpretation guide. [cited 16 June 2021]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44397. |

| 18. | Menzel G. [Equipment for recording isotonic muscle contractions with a mechanico-electric transducer]. Z Med Labortech. 1971;12:108-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wignyosumarto S, Mukhlas M, Shirataki S. Epidemiological and clinical study of autistic children in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Kobe J Med Sci. 1992;38:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21545] [Cited by in RCA: 28943] [Article Influence: 1206.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cliffe P. Measurement and recording during intensive patient care. Postgrad Med J. 1967;43:195-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nishikawa S, Ueno A, Ishida H, Nagata T, Hamasaki A, Koda N, Kido J, Wakano Y. [Gingival hyperplasia induced by nifedipine. Effect of nifedipine and EGF on cell proliferation in human gingival fibroblasts]. Nihon Shishubyo Gakkai Kaishi. 1986;28:168-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Amreen, Rizvi N. Frequency of depression and anxiety among tuberculosis patients. JTR. 2016;4:183-190. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Ruel-Kellermann M. [Women dentists]. Inf Dent. 1984;66:3265-3274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Aydin IO, Uluşahin A. Depression, anxiety comorbidity, and disability in tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: applicability of GHQ-12. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:77-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sulehri MA, Dogar IA, Sohail H, Mehdi Z, Azam M, Niaz O, Javed SM, Sajjad IA, Iqbal Z. Prevalence of depression among tuberculosis patients. APMC. 2010;4:133-137. |

| 26. | Punton S. Burford Nursing Development Unit. Self-medication. Nurs Times. 1985;80:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Khalid S, Williams CM, Reynolds SA. Is there an association between diet and depression in children and adolescents? Br J Nutr. 2016;116:2097-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |