Published online Apr 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i11.3541

Peer-review started: December 7, 2021

First decision: January 12, 2022

Revised: January 23, 2022

Accepted: February 23, 2022

Article in press: February 23, 2022

Published online: April 16, 2022

Processing time: 121 Days and 18.3 Hours

The airways of patients undergoing awake craniotomy (AC) are considered “predicted difficult airways”, inclined to be managed with supraglottic airway devices (SADs) to lower the risk of coughing or gagging. However, the special requirements of AC in the head and neck position may deteriorate SADs’ seal performance, which increases the risks of ventilation failure, severe gastric insufflation, regurgitation, and aspiration.

A 41-year-old man scheduled for AC with the asleep–awake–asleep approach was anesthetized and ventilated with a size 3.5 AIR-Q intubating laryngeal mask airway (LMA). Air leak was noticed with adequate ventilation after head rotation for allowing scalp blockage. Twenty-five minutes later, the LMA was replaced by an endotracheal tube because of a change in the surgical plan. After surgery, the patient consistently showed low tidal volume and was diagnosed with gastric insufflation and atelectasis using computed tomography.

This case highlights head rotation may cause gas leakage, severe gastric insufflation, and consequent atelectasis during ventilation with an AIR-Q intubating laryngeal airway.

Core Tip: AIR-Q intubating laryngeal airway is a feasible airway management method for predicted difficult airways and has been proven to involve fewer complications and a shorter ventilation duration than fiberoptic intubation. This case highlights that head rotation during ventilation with an AIR-Q intubating laryngeal airway may lead to gas leakage, severe gastric insufflation, and consequent atelectasis; this indicates that physicians should pay attention to patient position changes when using laryngeal mask airway.

- Citation: Zhao Y, Li P, Li DW, Zhao GF, Li XY. Severe gastric insufflation and consequent atelectasis caused by gas leakage using AIR-Q laryngeal mask airway: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(11): 3541-3546

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i11/3541.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i11.3541

The use of supraglottic airway devices (SADs) has been proven to be a feasible airway management method for awake craniotomy (AC) to lower the risk of coughing or gagging during the transition to the awake state[1]. Recently, a retrospective analysis of 30 cases of AC reported that patients receiving laryngeal mask airway (LMA) had fewer complications and a shorter ventilation duration than patients who underwent fiberoptic intubation[2]. Considering the requirements of craniotomy and scalp blocks, head rotation and neck flexion may influence the performance of SADs including oropharyngeal leak pressure, ventilation, and fiberoptic view[3,4]. Gastric insufflation and regurgitation were also reported by studies using SADs[3,5,6]. There are no clinical data on gastric insufflation and regurgitation in AC, and the current reviews do not provide suggestions to prevent these complications[1,7,8]. Here, we report a case of severe gastric insufflation and consequent atelectasis caused by gas leakage using AIR-Q LMA during preparation for craniotomy.

A 41-year-old man was admitted for paroxysmal unconsciousness for 7 d.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this report and any accompanying images. A 41-year-old man (weight, 65 kg; height, 168 cm) was diagnosed with postoperative recurrence of a right frontotemporal glioma and was scheduled for AC with the asleep–awake–asleep approach[1] on July 24, 2020.

Preoperative medication included daily doses of phenobarbitone 120 mg and carbamazepine 600 mg. He did not receive premedication and fasted for longer than 8 h on the day of surgery. After attaching the monitors and securing peripheral venous access, pre-oxygenation was performed to reach an exhaled oxygen concentration > 90%. Anesthesia was induced with a bolus injection of propofol (2 mg/kg) and sufentanil (0.2 μg/kg). Bag-mask ventilation with the head-tilt-chin lift, jaw-thrust maneuver was applied and rated Grade 1 using Han’s grading scale for mask ventilation[9]. At EEG stage D, a size 3.5 AIR-Q intubating laryngeal airway (Cookgas® company) was promptly inserted following a standard insertion technique. The sealing pressure was optimized by inflating the cuff until the cessation of the air leak sound from the mouth[10].

Large chest elevation amplitude, normal pulmonary auscultation, no epigastric audible sound, and standard end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) curve were achieved. Volume-control ventilation was adopted with the following breath parameters: 500 mL/L O2, gas flow 3 L/min, VT 6 mL/kg, I:E 1:2, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) = 0 cmH2O, and peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) = 18 cmH2O. The respiratory rate was adjusted to maintain ETCO2 between 35 and 40 mmHg. Sevoflurane inhalation and target-controlled infusion of remifentanil were administered to maintain anesthesia. Scalp nerve block was performed using 20 mL ropivacaine 500 mg/L. To facilitate ultrasound-guided bilateral greater and lesser occipital nerve blocks, the patient’s head was rotated approximately 45° to the left and right, respectively. Air leak sound from the mouth with obvious chest expansion and increased PIP (23 cmH2O) was noticed and assessed as “adequate” ventilation using a three-point ventilation score[11]. After approximately 25 min of administering the scalp block, the anesthesia provider was informed that the surgical plan would change to craniotomy under general anesthesia. After administering an induction dose of cisatracurium (0.15 mg/kg), the LMA was withdrawn, and an endotracheal tube (ID 7.5) was successfully inserted using a video laryngoscope at the first attempt. Ventilation parameters remained unchanged, except for PEEP 5 cmH2O and PIP 22 cmH2O. The length of surgery was 460 min. At the completion of the surgery, sevoflurane was stopped, and remifentanil was adjusted to 2 μg/mL. Patient consciousness and spontaneous breathing were restored in 13 min. However, VT was consistently low (160-200 mL) even after a standard lung recruitment maneuver (RM).

The patient had no history of any medical illness other than the diagnosis from the previous surgery.

This patient is with no family history.

Breath sounds decreased bilaterally.

Intraoperative PO2 of arterial blood gas was between 214 and 225 mmHg.

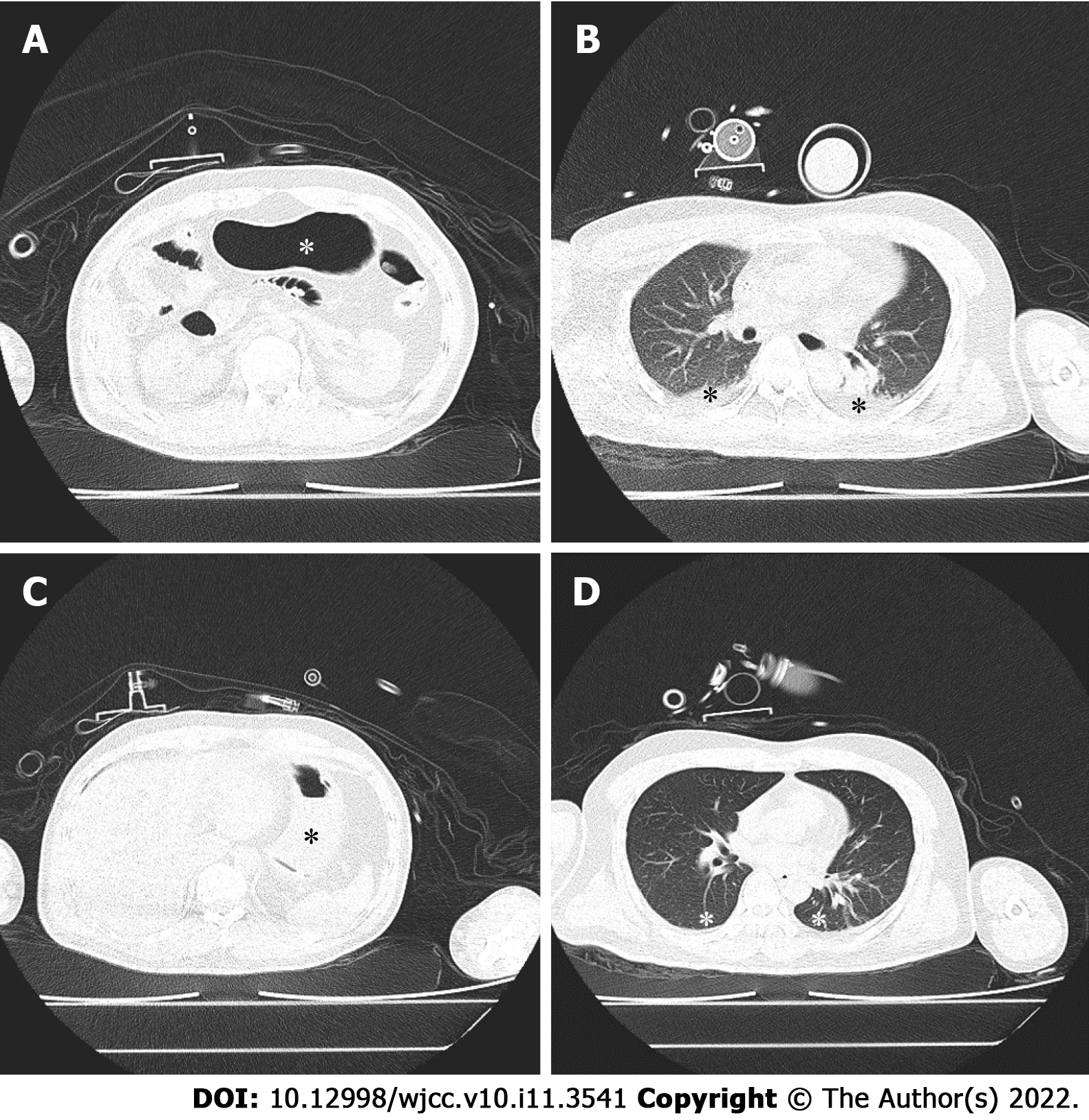

A lung computed tomography (CT) scan was performed in the hybrid operating room. Before gastric decompression, gastric insufflation (Figure 1A, asterisk) and atelectasis with air bronchogram (Figure 1B, asterisk) were observed. In contrast, after gastric decompression and RM, the stomach was deflated (Figure 1C, asterisk), and the atelectatic lung tissue (Figure 1D, asterisk) was re-aerated.

Abdominal and chest CT scans revealed severe gastric insufflation (Figure 1A), elevation of the bilateral diaphragm dome to the lower edge of the seventh thoracic vertebral body, and atelectasis of the bilateral lower lobes (Figure 1B).

A nasogastric tube was promptly inserted, through which a large amount of gas was released. After another RM, VT was restored to 300 mL. The second CT scan showed gastric deflation (Figure 1C), descent of the bilateral diaphragm dome to the lower edge of the ninth thoracic vertebral body, and a great reduction in the atelectasis region (Figure 1D).

The patient was transferred to the neurological intensive care unit, extubated after 48 h of synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation without other pulmonary complications, and discharged from the hospital on the 7th postoperative day.

This is the first report to describe severe gastric insufflation and consequent atelectasis during mechanical ventilation with an AIR-Q LMA. Contrary to the endotracheal tube, SADs enable effective ventilation with risks of gastric insufflation, consequent regurgitation, and pulmonary aspiration[8]. These risks may increase upon changing the head and neck position, which is required for certain surgical and anesthetic procedures, such as AC and scalp block[1]. Neck flexion decreases longitudinal tension in the anterior pharyngeal muscles and reduces the pharyngeal anteroposterior diameter, resulting in significant impairment of ventilation and alignment between the SAD and glottis with increased oropharyngeal leak pressure. Conversely, neck extension increases the pharyngeal anteroposterior diameter by elevating the laryngeal inlet and reduces oropharyngeal leak pressure without impairing ventilation. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that SAD performance was not significantly affected by the rotation of the head and neck, and the intracuff pressure of LMAs was standardized at 60 cmH2O (5.9 kPa)[7]. In the present case, peak inspiratory pressure-guided intracuff pressure was applied to reduce postoperative pharyngolaryngeal complications[12]. This technique might have led to a lower intracuff pressure and cuff volume and consequently impaired seal performance of LMA as the head and neck positions changed. However, higher intracuff pressure does not necessarily improve sealing performance. A recent study reported that an intracuff pressure of 20 cmH2O reduced the incidence of gastric insufflation to 35%, compared with that of 60 cmH2O (48%)[6]. Moreover, gastric insufflation detected with ultrasonography[6] is reported to be significantly more frequent than that with epigastric auscultation[8]. Prolonged duration of surgery and mechanical ventilation lead to atelectasis and other pulmonary complications[13]. However, the difference in the outcomes between the first RM and the RM after gastric decompression indicated that gastric insufflation was an important factor aggravating atelectasis. Furthermore, by continuously stretching the diaphragm for approximately 10 h, gastric insufflation might have led to diaphragmatic dysfunction, decreasing the patient’s postoperative VT[14].

Because of immobilization of the patient’s head and limited access of the anesthetist to the patient, airway management in AC should be treated as a predicted difficult airway. Therefore, gastric insufflation with SAD ventilation, which may lead to regurgitation and aspiration, should be prevented, detected, and addressed early. An alternative solution may be ventilation with a SAD embedding a channel for orogastric tube placement, insertion of an orogastric tube, and careful titration of intracuff pressure for various head and neck positions during the asleep period. Further, the orogastric tube can be removed at the beginning of the transition to the awake period and reinserted if a SAD is replaced in the post-awake phase. If available, ultrasonography for early detection of gastric insufflation and measurement of gastric volume is significantly superior to epigastric auscultation. Moreover, ultrasonography may help monitor the development of atelectasis[15] and diaphragm function[16].

Our report suggests that head rotation may lead to gas leakage, severe gastric insufflation, and consequent atelectasis during ventilation with an AIR-Q intubating laryngeal airway.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Respiratory system

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bairwa DBL, Chan SM S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Meng L, McDonagh DL, Berger MS, Gelb AW. Anesthesia for awake craniotomy: a how-to guide for the occasional practitioner. Can J Anaesth. 2017;64:517-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Grabert J, Klaschik S, Güresir Á, Jakobs P, Soehle M, Vatter H, Hilbert T, Güresir E, Velten M. Supraglottic devices for airway management in awake craniotomy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Park SH, Han SH, Do SH, Kim JW, Kim JH. The influence of head and neck position on the oropharyngeal leak pressure and cuff position of three supraglottic airway devices. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:112-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim MS, Park JH, Lee KY, Choi SH, Jung HH, Kim JH, Lee B. Influence of head and neck position on the performance of supraglottic airway devices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Qamarul Hoda M, Samad K, Ullah H. ProSeal versus Classic laryngeal mask airway (LMA) for positive pressure ventilation in adults undergoing elective surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD009026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hell J, Pohl H, Spaeth J, Baar W, Buerkle H, Schumann S, Schmutz A. Incidence of gastric insufflation at high compared with low laryngeal mask cuff pressure: A randomised controlled cross-over trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021;38:146-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kulikov A, Lubnin A. Anesthesia for awake craniotomy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2018;31:506-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Potters JW, Klimek M. Awake craniotomy: improving the patient's experience. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28:511-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Han R, Tremper KK, Kheterpal S, O'Reilly M. Grading scale for mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ali A, Canturk S, Turkmen A, Turgut N, Altan A. Comparison of the laryngeal mask airway Supreme and laryngeal mask airway Classic in adults. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:1010-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Keller C, Brimacombe JR, Keller K, Morris R. Comparison of four methods for assessing airway sealing pressure with the laryngeal mask airway in adult patients. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:286-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang MH, Zhang DS, Zhou W, Tian SP, Zhou TQ, Sui W, Zhang Z. Effects of Peak Inspiratory Pressure-Guided Setting of Intracuff Pressure for Laryngeal Mask Airway Supreme™ Use during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Invest Surg. 2021;34:1137-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, Paluzie G, Vallès J, Castillo J, Sabaté S, Mazo V, Briones Z, Sanchis J; ARISCAT Group. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1338-1350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 632] [Cited by in RCA: 815] [Article Influence: 54.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goligher EC, Brochard LJ, Reid WD, Fan E, Saarela O, Slutsky AS, Kavanagh BP, Rubenfeld GD, Ferguson ND. Diaphragmatic myotrauma: a mediator of prolonged ventilation and poor patient outcomes in acute respiratory failure. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:90-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Frassanito L, Sonnino C, Pitoni S, Zanfini BA, Catarci S, Gonnella GL, Germini P, Vizzielli G, Scambia G, Draisci G. Lung ultrasound to monitor the development of pulmonary atelectasis in gynecologic oncologic surgery. Minerva Anestesiol. 2020;86:1287-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fossé Q, Poulard T, Niérat MC, Virolle S, Morawiec E, Hogrel JY, Similowski T, Demoule A, Gennisson JL, Bachasson D, Dres M. Ultrasound shear wave elastography for assessing diaphragm function in mechanically ventilated patients: a breath-by-breath analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24:669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |