Published online Apr 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3284

Peer-review started: November 23, 2021

First decision: January 11, 2022

Revised: February 4, 2022

Accepted: February 23, 2022

Article in press: February 23, 2022

Published online: April 6, 2022

Processing time: 125 Days and 21.2 Hours

With the increasing prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the incidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) bacteremia has also increased. As a common affliction of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients, M. tuberculosis infection is associated in these patients with severe sepsis and high mortality. In contrast, M. tuberculosis bacteremia is rarely seen in HIV-negative patients, and M. tuberculosis has never been reported from the blood of patients with liver cirrhosis.

We evaluated a 55-year-old Chinese male patient who had been admitted to the hospital with abdominal distension of unknown cause of one-week duration, accompanied by diarrhea, shortness of breath, and occasional fever. Based on these indicators of abnormal inflammation and fever, we suspected the presence of an infection. Although evidence of microbial infection was not found in routine clinical tests and the patient did not show typical clinical symptoms of infection with M. tuberculosis, next-generation sequencing of blood samples nevertheless demonstrated the presence of M. tuberculosis, which was subsequently isolated from blood samples grown in conventional BacT/ALERT FA blood culture bottles.

Our findings demonstrate that HIV-negative liver cirrhosis patients can also be infected with M. tuberculosis.

Core Tip: Our findings are interesting in two ways. First, although Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) bacteremia is a common occurrence in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients, it has rarely been reported from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative patients. We report here, however, a case of M. tuberculosis bacteremia in an HIV-negative patient diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. This finding should alert physicians to consider the possibility of M. tuberculosis bacteremia in patient populations not usually considered to be vulnerable to such infections. Second, our successful use of next-generation sequencing for detection of M. tuberculosis in the blood should be of interest to physicians as a tool for early detection of microbial infection.

- Citation: Lin ZZ, Chen D, Liu S, Yu JH, Liu SR, Zhu ML. Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteremia in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient with liver cirrhosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(10): 3284-3290

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i10/3284.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3284

Despite intense worldwide efforts for treatment and prevention of this disease by the medical community, tuberculosis remains one of the most common causes of death from a single infectious pathogen. China has the third-highest burden of tuberculosis in the world, after India and Indonesia[1]. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) can directly invade the human gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, and skin. It can also infect other parts of the body through spread of this bacterium from the primary lesions through the blood. M. tuberculosis bacteremia is commonly found in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients, and it can also occur in patients with malignant tumors, diabetes, and rheumatic diseases[2]. However, M. tuberculosis has been rarely reported in patients with liver disease. In this report, we describe a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative, cirrhotic patient with M. tuberculosis bacteremia.

A 55-year-old man reported persistent abdominal distension of one week duration, with no obvious underlying cause; the distension was accompanied by diarrhea, shortness of breath, and occasional fever.

The patient showed no symptoms of illness other than the one-week duration of persistent abdominal distension with diarrhea, shortness of breath, and occasional fever.

Medical records indicated a two-year history of abnormal liver function without treatment.

The patient had a history of smoking and alcohol abuse. There was no family history of other diseases.

Physical examination of the skin showed the evidence of spider nevi, jaundice of skin or sclera, and facial features associated with liver disease, but no evidence of palmar erythema. Auscultation revealed abnormal breath sounds over both lungs and a decreased breath sounds over the right lower lung. Examination of the abdomen showed abdominal distension but no tenderness or rebound pain, splenomegaly, or percussion pain in the liver area. There were also no signs of asterixis.

Laboratory analysis of blood samples indicated abnormal liver function: total bilirubin, 221.52 μmol/L; direct bilirubin, 138.76 μmol/L; indirect bilirubin, 82.8 μmol/L; total protein, 48.9 g/L; albumin, 21.6 g/L; alanine aminotransferase, 57 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 73 U/L; C-reactive protein, 34 mg/L; serum amyloid A, 92 mg/L; procalcitonin, 1.820 ng/mL; total lymphocyte count, 220/μL; HBsAg, 0.00 IU/mL; HBsAb, 29.19 mIU/mL, HBeAg, 0.38 S/CO; HBeAb, 1.30 S/CO; HBcAg, 8.88 S/CO; hepatitis A antibodies immunoglobulin (Ig) M, negative; hepatitis C virus antibody, negative; hepatitis D antigen, negative; hepatitis D antibody, negative; hepatitis E antibody IgM, negative; hepatitis E antibody IgG, weakly positive; cytomegalovirus antibody IgG, positive; cytomegalovirus antibody IgM, negative; coxsackie virus antibody IgG, positive; coxsackie virus antibody IgM, negative; antinuclear antibody, negative; antimitochondrial antibody, negative; anti-Ro-52 antibody, negative; anti-mitochondrial antibody type 2, negative; anti-SSA antibody, negative; anti-SSB antibody, negative; anti-CENP-B antibody, negative; antihistone antibodies, negative; anti-Jo-1 antibody, negative; anti-Sm antibody, negative; anti-Scl-70 antibody, negative; anti-soluble liver antigen/pancreas antigen antibody, negative; anti-smooth muscle antibody, negative; anti-liver and kidney microsome antibodies, negative; anti-PM-Scl antibody, negative; anti-PCNA antibody, negative.

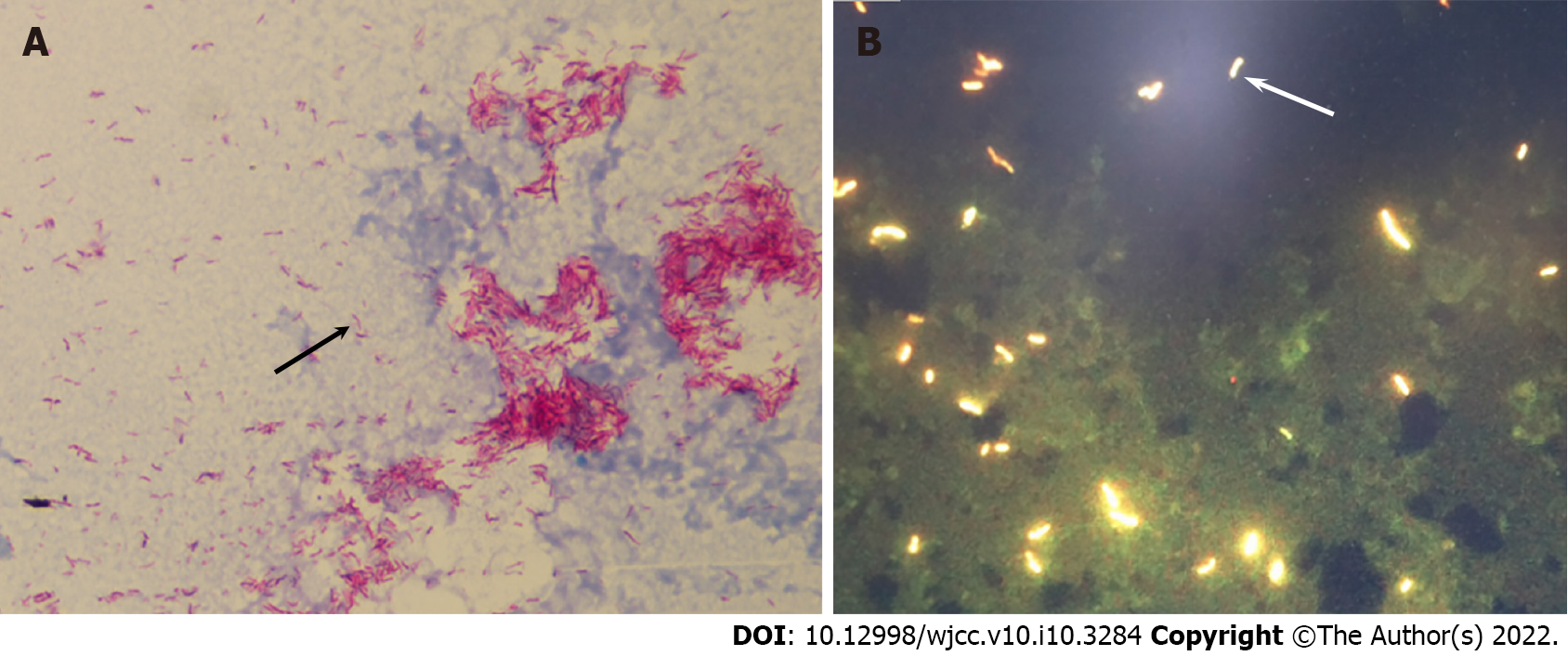

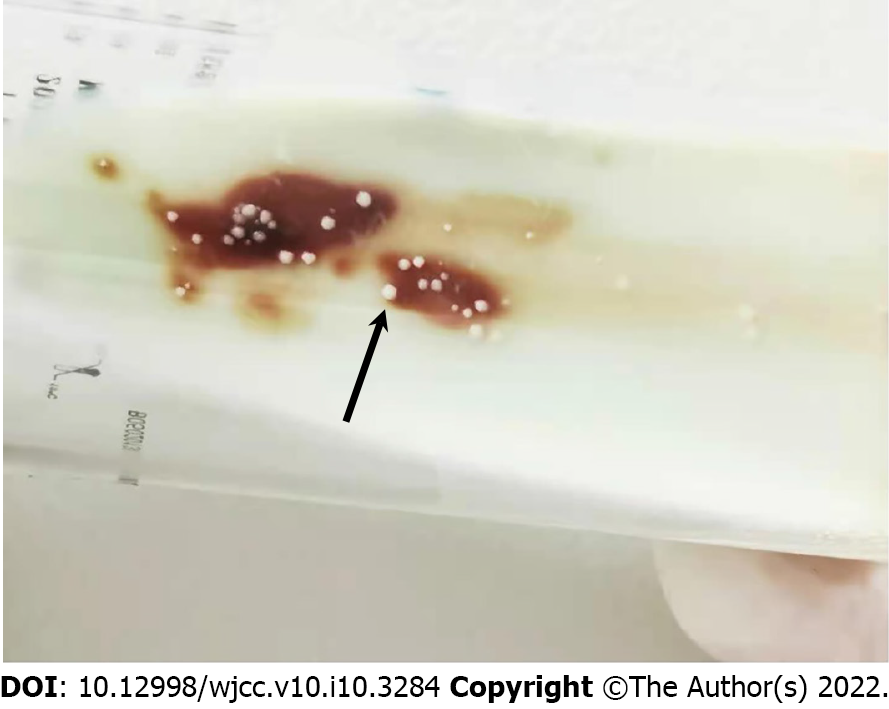

Examination of ascites fluid showed a positive Rivalta test; ascites cell counts showed 1.6 × 109/L nucleated cells, 76% of which were neutrophils, 10% mononuclear macrophages, 12% lymphocytes, and 2% mesothelial cells. Conventional cultures of the patient’s blood and ascitic fluid were negative for bacterial growth; sputum culture did not show any pathogenic bacteria. However, screening for microbial pathogens in blood samples with next generation sequencing demonstrated the presence of M. tuberculosis infection in this patient (Table 1). The presence of acid-fast bacilli in these samples was confirmed by blood smears (Figure 1A) and by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 1B) of blood cultured in conventional BacT/ALERT FA blood culture bottles. Blood cultured on Lowenstein-Jenden medium yielded white colonies, which were identified as M. tuberculosis by MALDI-TOF MS (France, Bio-Mérieux) (Figure 2).

| Species complex | Species | ||||

| Chinese name | Latin name | Number of detected sequences | Chinese name | Latin name | Number of detected sequences |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex | Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex | 166 | - | - | - |

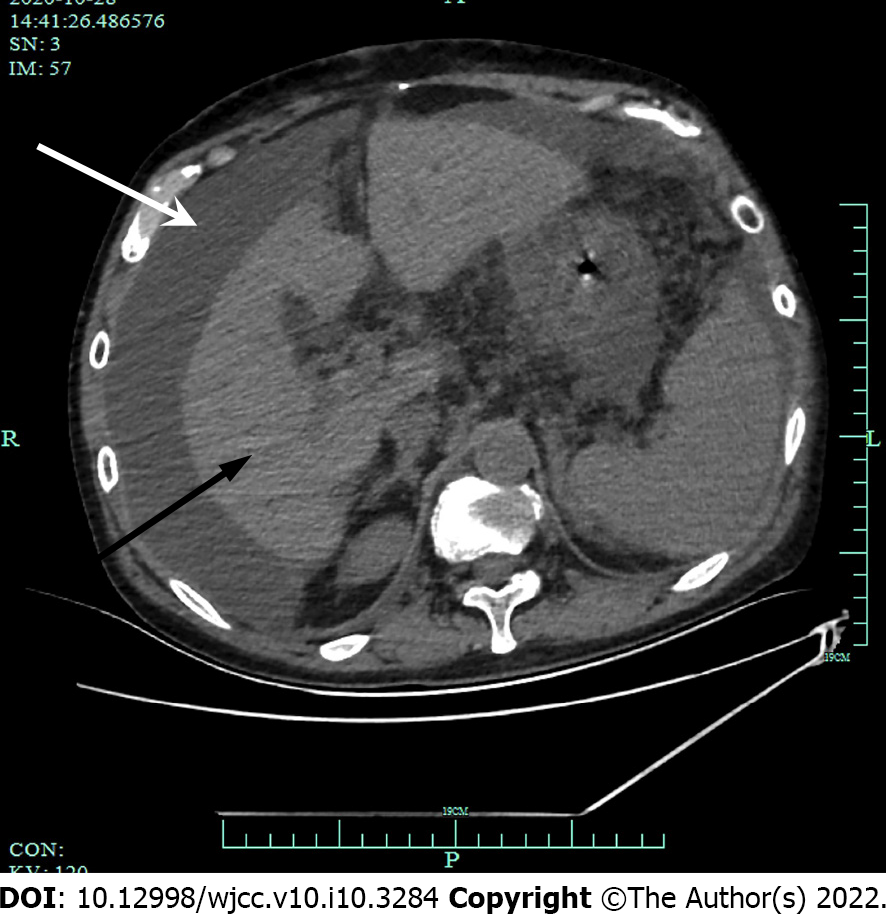

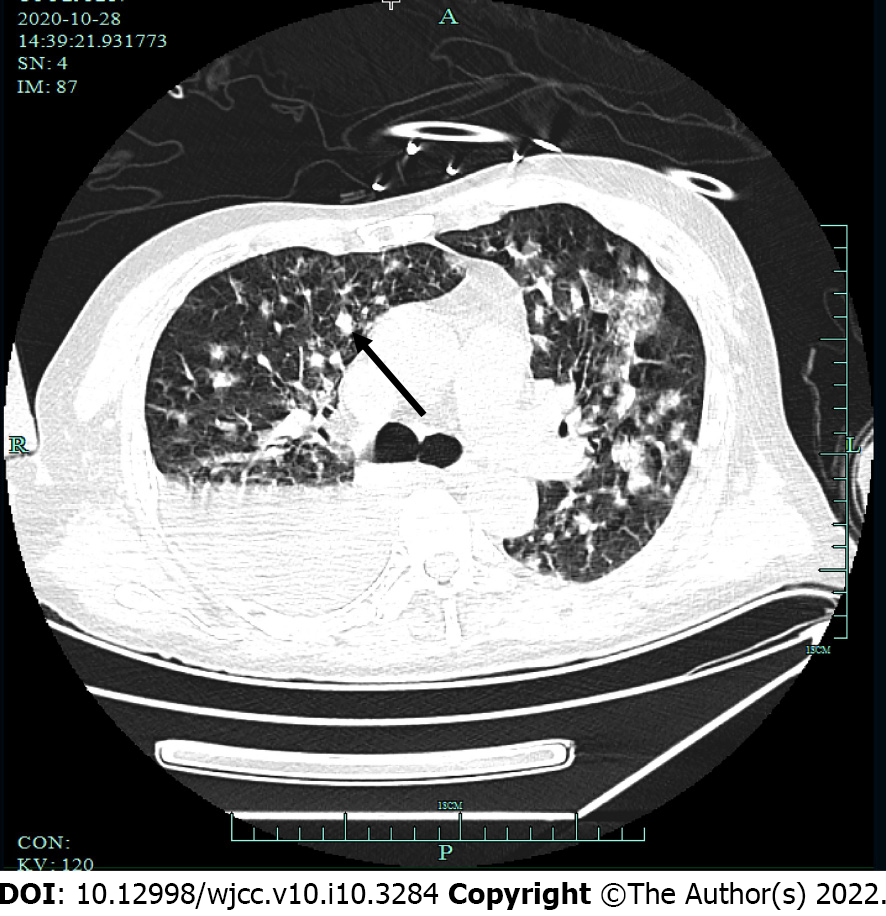

Computed tomography (CT) scans showed abdominal (Figure 3) and pelvic effusion and bilateral pleural effusion, with greater effusion in the right pleura. Multiple patchy high-density shadows were seen in both lungs, with blurred borders. Although there were no obvious signs of swollen lymph node shadows in the mediastinum, there were multiple areas of inflammation in both lungs (Figure 4). CT scans indicated liver cirrhosis and multiple cystic foci in the liver.

Chronic liver failure, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, ascites.

The patient was treated with supplementary oxygen delivered by a nasal cannula. He was also treated with spironolactone (40 mg, three times a day) and torasemide (10 mg, once a day) for diuretic therapy and magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate (200 mg, once a day) for hepatoprotective therapy. To control the large volume of ascites, the patient’s excess fluid was treated by abdominal puncture drainage, and the infection was treated with piperacillin sulbactam (6 g, every 12 h), biapenem (300 mg, every 6 h) and micafungin (150 mg, once a day).

Although the patient was in severe condition at high risk of respiratory and cardiac arrest at any time, he discharged himself from the hospital against medical advice.

Bacteremia is a serious systemic infectious disease. The most commonly observed pathogen in bacteremia is Escherichia coli, followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus[3].

There have been fewer reports of M. tuberculosis bacteremia, which is usually diagnosed by a M. tuberculosis-positive blood culture. With the increasing number of AIDS patients, however, the incidence of M. tuberculosis bacteremia has also been gradually increasing[4]. Among AIDS patients, M. tuberculosis bacteremia is a common and life-threatening disease[5,6], and it is often associated with severe sepsis[7,8] and high mortality[9] in these patients. The common symptoms of AIDS patients infected with M. tuberculosis bacteremia include fever, lymphopenia, pulmonary symptoms, weight loss, and cough with sputum[2,10].

Compared to AIDS patients, there have been fewer reports of M. tuberculosis bacteremia in HIV-negative patients[11,12]. Chiu et al[10] have pointed out that the incidence of M. tuberculosis bacteremia in HIV-positive patients is significantly higher than that in HIV-negative patients. M. tuberculosis bacteremia can also occur in other immunocompromised patients, such as those with malignant tumors, diabetes, and rheumatic diseases[2].

Cirrhosis of the liver is an immunocompromised condition that increases the vulnerability of patients to various infections[13]. The most common bacteremia pathogens in patients with liver cirrhosis include Enterobacter, Enterococcus, and Streptococcus[14]. Compared with non-cirrhotic patients, cirrhotic patients with bacteremia show significantly higher mortality as well as greater risk of morbidity and longer hospital stays[3].

Several less common pathogens are also more prevalent and more virulent in patients with liver cirrhosis. Studying liver patients in a hospital in France, Kovacevic and Lakshmanan[14] found that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia is present in 35% of patients with liver cirrhosis. Citing several studies in Scandinavia and the United States, Bunchorntavakul and Chavalitdhamrong[15] reported that patients with liver cirrhosis show an increased incidence and heightened virulence of M. tuberculosis infection, which frequently manifests as peritonitis. However, there have been very few reports of M. tuberculosis bacteremia in patients with liver cirrhosis.

The clinical symptoms of the patient in this study included pulmonary abnormalities, abdominal distension, and occasional fever, and lymphopenia, similar to the reports of Chiu et al[10] in HIV-negative patients. Our patient did not show any of the typical symptoms of M. tuberculosis infection such as cough, sputum expectoration, fatigue, or night sweats. However, use of next generation sequencing to screen the patient’s blood samples for microbial pathogens revealed infection with M. tuberculosis. M. tuberculosis was later isolated from samples of the patient’s blood grown in conventional BacT/ALERT FA blood culture bottles, thus confirming the sequencing results. We were unable to determine whether the primary disease of M. tuberculosis in this patient was an intrapulmonary or extrapulmonary infection because both ascites and blood cultures eventually showed growth of M. tuberculosis and M. tuberculosis can spread to different sites in the bloodstream. Although the patient's conventional sputum culture showed no abnormal colony growth, it was possible that laboratory culture time was insufficient to obtain M. tuberculosis.

In 2005, Hanscheid et al[16] reported that M. tuberculosis can grow in conventional BacT/ALERT FA blood culture bottles, which can be used to reliably diagnose M. tuberculosis bacteremia. However, because of sparse subsequent reports, few clinicians are aware that M. tuberculosis can grow in conventional BacT/ALERT FA blood culture bottles. Our detection of M. tuberculosis in the patient’s blood with next-generation sequencing indicates that the use of advanced technologies can also greatly assist in clinical testing for elusive or unknown pathogens.

The findings presented here can raise the awareness of doctors to the possibility that even HIV-negative patients, including HIV-negative patients with liver cirrhosis, may develop M. tuberculosis bacteremia.

Although M. tuberculosis bacteremia is a common occurrence among AIDS patients, there have been very few reports of HIV-negative cirrhosis patients with M. tuberculosis bacteremia. We have shown that next-generation sequencing of pathogenic microorganisms can be used when the cause of infection cannot be found by routine laboratory tests. After sequencing indicated the presence of M. tuberculosis in patient blood in this clinical case, later isolation of M. tuberculosis from blood samples grown in ordinary blood culture media further confirmed the sequencing results.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ke X, Syahputra DA, Teragawa H S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gao CC

| 1. | Chakaya J, Khan M, Ntoumi F, Aklillu E, Fatima R, Mwaba P, Kapata N, Mfinanga S, Hasnain SE, Katoto PDMC, Bulabula ANH, Sam-Agudu NA, Nachega JB, Tiberi S, McHugh TD, Abubakar I, Zumla A. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020 - Reflections on the Global TB burden, treatment and prevention efforts. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;113 Suppl 1:S7-S12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 577] [Article Influence: 144.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu X, Bian S, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Yang Q, Wang P, Xu Y, Shi X, Chemaly RF. The characteristics of patients with mycobacterium tuberculosis blood stream infections in Beijing, China: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen HY, Hsu YC. Afebrile Bacteremia in Adult Emergency Department Patients with Liver Cirrhosis: Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | McDonald LC, Archibald LK, Rheanpumikankit S, Tansuphaswadikul S, Eampokalap B, Nwanyanawu O, Kazembe P, Dobbie H, Reller LB, Jarvis WR. Unrecognised Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteraemia among hospital inpatients in less developed countries. Lancet. 1999;354:1159-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Barr DA, Kerkhoff AD, Schutz C, Ward AM, Davies GR, Wilkinson RJ, Meintjes G. HIV-Associated Mycobacterium tuberculosis Bloodstream Infection Is Underdiagnosed by Single Blood Culture. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Barr DA, Lewis JM, Feasey N, Schutz C, Kerkhoff AD, Jacob ST, Andrews B, Kelly P, Lakhi S, Muchemwa L, Bacha HA, Hadad DJ, Bedell R, van Lettow M, Zachariah R, Crump JA, Alland D, Corbett EL, Gopinath K, Singh S, Griesel R, Maartens G, Mendelson M, Ward AM, Parry CM, Talbot EA, Munseri P, Dorman SE, Martinson N, Shah M, Cain K, Heilig CM, Varma JK, von Gottberg A, Sacks L, Wilson D, Squire SB, Lalloo DG, Davies G, Meintjes G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis bloodstream infection prevalence, diagnosis, and mortality risk in seriously ill adults with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:742-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Andrews B, Semler MW, Muchemwa L, Kelly P, Lakhi S, Heimburger DC, Mabula C, Bwalya M, Bernard GR. Effect of an Early Resuscitation Protocol on In-hospital Mortality Among Adults With Sepsis and Hypotension: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1233-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 36.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Feasey NA, Banada PP, Howson W, Sloan DJ, Mdolo A, Boehme C, Chipungu GA, Allain TJ, Heyderman RS, Corbett EL, Alland D. Evaluation of Xpert MTB/RIF for detection of tuberculosis from blood samples of HIV-infected adults confirms Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteremia as an indicator of poor prognosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2311-2316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mathuram AJ, Michael JS, Turaka VP, Jasmine S, Carey R, Ramya I. Mycobacterial blood culture as the only means of diagnosis of disseminated tuberculosis in advanced HIV infection. Trop Doct. 2018;48:100-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chiu YS, Wang JT, Chang SC, Tang JL, Ku SC, Hung CC, Hsueh PR, Chen YC. Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteremia in HIV-negative patients. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:355-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tan CK, Lai CC, Liao CH, Chou CH, Hsu HL, Huang YT, Hsueh PR. Mycobacterial bacteraemia in patients infected and not infected with human immunodeficiency virus, Taiwan. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:627-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Petrillo VF, Amaral AA, Moreira Jd, Jardim SB, Severo LC. A case report of vascular catheter-associated bacteremia caused by mycobacterium tuberculosis in a non-immunosuppressed patient. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1999;41:203-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bonnel AR, Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Immune dysfunction and infections in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:727-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kovacevic LG, Lakshmanan Y. Re: tonsillectomy does not improve bedwetting: results of a prospective controlled trial. C. M. Kalorin, J. Mouzakes, J. P. Gavin, T. D. Davis, P. Feustel and B. A. Kogan. J Urol 2010; 184: 2527-2531. J Urol. 2011;186:352-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bunchorntavakul C, Chavalitdhamrong D. Bacterial infections other than spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:158-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hanscheid T, Monteiro C, Cristino JM, Lito LM, Salgado MJ. Growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in conventional BacT/ALERT FA blood culture bottles allows reliable diagnosis of Mycobacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:890-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |