Published online Jan 7, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.296

Peer-review started: May 18, 2021

First decision: July 5, 2021

Revised: July 15, 2021

Accepted: November 30, 2021

Article in press: November 30, 2021

Published online: January 7, 2022

Processing time: 225 Days and 22.9 Hours

Primary intracranial alveolar soft-part sarcoma (PIASPS) is a rare malignancy. We aimed to investigate the clinical profiles and outcomes for PIASPS.

We firstly reported five consecutive cases from our institute. Then, the cases from previous studies were pooled and analyzed to delineate the characteristics of this disease. Our cohort included two males and three females. The median age was 21-years-old (range: 8-54-years-old). All the patients received surgical treatment. Gross total resection (GTR), radiotherapy, and chemotherapy were administered in 3 patients, 4 patients, and 1 patient, respectively. After a median follow-up of 36 mo, tumor progression was noticed in 4 patients; and 3 patients died of the disease. Pooled data (n = 14) contained 5 males and 9 females with a median age of 19 years. The log-rank tests showed that GTR (P = 0.011) could prolong progression-free survival, and radiotherapy (P < 0.001) resulted in longer overall survival.

Patients with PIASPS suffer from poor outcomes. Surgical treatment is the first choice, and GTR should be achieved when the tumor is feasible. Patients with PIASPS benefit from radiotherapy, which should be considered as a part of treatment therapies.

Core Tip: Alveolar soft part sarcoma, or alveolar soft-part sarcoma (ASPS), is reportedly a rare tumor with a high recurrent rate. Current understanding of primary intracranial ASPS, or primary intracranial ASPS (PIASPS), is limited to case reports or small case series that preclude statistical analysis of outcomes (e.g., progression-free survival or overall survival). In this article, we first reported 5 consecutive cases from our institute. Then, the 9 cases from previous studies were pooled and analyzed to delineate the characteristics of this disease. We found PIASPS was a rare malignancy and predominately affected young females. Patients with PIASPS suffer from poor outcomes, characterized by a high tendency of recurrence. Surgical treatment is the first choice and gross total resection should be achieved when the tumor is feasible. Besides, PIASPS benefit from radiotherapy, which should be considered as a part of treatment therapies.

- Citation: Chen JY, Cen B, Hu F, Qiu Y, Xiao GM, Zhou JG, Zhang FC. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of primary intracranial alveolar soft-part sarcoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(1): 296-303

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i1/296.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.296

Alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) accounts for less than 1% of soft-tissue sarcoma[1]. Christopherson et al[2] first described ASPS as a unique variant from general soft-tissue sarcoma in 1952. ASPSs are characterized by pseudoalveolar architecture and various cytoplasmic inclusion bodies with diastase-resistant periodic acid-Schiff crystalline[3]. ASPSCR1-TFE3 (or ASPL-TFE3), a fusion gene, has been shown to contribute to tumor genesis and be particularly informative in diagnosing ASPS[4,5]. While the exact cell (myogenic or neurogenic) origin of ASPS is disputable, the sarcoma entity is mainly found in the lower extremities and, to a lesser extent, in the upper extremity or trunk, head and neck, and abdomen[6]. ASPSs tend to metastasize, and brain is one of the most common targets[7,8]. Accordingly, intracranial ASPS presents as primary and metastatic ASPS, with the former being less common. The current understanding of primary intracranial ASPS (PIASPS) was based on 8 case reports (9 cases)[3,9-15]. In this study, we firstly reported 5 consecutive cases from our institute to delineate the clinical characteristics of this disease. Then, the cases from previous studies were pooled to evaluate the efficacy of treatment options in patients' outcomes with PIASPS.

There were 5 patients with PIASPS between 2005 and 2019, including 2 males and 3 females (Table 1). The median age of the 5 cases was 21 years (range: 8-54-years-old). One patient was asymptomatic, and the intracranial lesion was found because of routine computed tomography (CT) for a minor cranial injury. The other 4 patients suffered from various symptoms, including headache in 3 cases, aphasia, muscle weakness, each in 1 case.

| Ref. | Sex/age | Location/diameter | Treatment strategies | Salvage treatments and outcomes |

| Bots et al[9], 1988 | M/9 yr | Pituitary gland | NGTR + RT (45 Gy) | Metastases (12.3 mo, GTR); alive (40 mo) |

| Bodi et al[3], 2009 | F/39 yr | L temporal/6 cm | GTR | Tumor free; NED (10 mo) |

| Das et al[10], 2012 | F/17 yr | Bifrontal | GTR + RT | Tumor free; NED (4 mo) |

| Mandal et al[11], 2013 | F/32 yr | R parietal | GTR | |

| Ahn et al[12], 2014 | F/9 yr | R CPA/4.5 cm | NGTR + RT (54 Gy) | LR (14 mo, NGTR + GKS + CMT1); alive (56 mo) |

| Emmez et al[13], 2015 | F/11 yr | L frontal | GTR + RT (54 Gy) + CMT2 | LR (45 mo, GTR + chemotherapy); alive (54 mo) |

| Tao et al[15], 2016 | F/28 yr | L frontal/4.1 cm | GTR + RT | Tumor free; alive (27 mo) |

| Tao et al[19], 2017 | M/13 yr | R temporal/3.7 cm | NGTR + RT | LR (14 mo); DOD (24 mo) |

| Kumar et al[14], 2019 | M/21 yr | L post. fossa | GTR | Tumor free; NED (8 mo) |

| Present | M/24 yr | R frontal/3.5 cm | GTR + RT (52 Gy) | Tumor free; NED (25 mo) |

| Present | F/53 yr | Ant. skull base/5.0 cm | NGTR + RT (46 Gy) + CMT3 | LR (10 mo, surg.); AWD (36 mo) |

| Present | M/21 yr | R parietooccipital/4.0 cm | GTR | Metastases (15 mo); DOD (26 mo) |

| Present | F/8 yr | R temporal/2.8 cm | NGTR + RT | LR (8 mo, surg.); DOD (50 mo) |

| Present | F/16 yr | L parietal/3.0 cm | GTR + RT (42 Gy) | LR (32 mo, surg. + CMT1 + RT); DOD (61 mo) |

For the 4 symptomatic patients, the median duration from the onset of symptoms to the diagnosis was 7.5 mo (range: 2-24 mo). Worsened headache (2/3) and muscle weakness (1/1) were reported after the onset of symptoms.

One patient had an injury in the spinal column in his childhood, which was well treated by surgery. No medical history was reported for the other 4 patients.

Critical and general signs were within the normal range for 5 patients. The neurological examination showed that papilledema was found in 2 patients, diplopia in 1 patient, and myasthenia of the upper right limb in 1 patient.

Routine blood and urine tests of the 5 patients were normal.

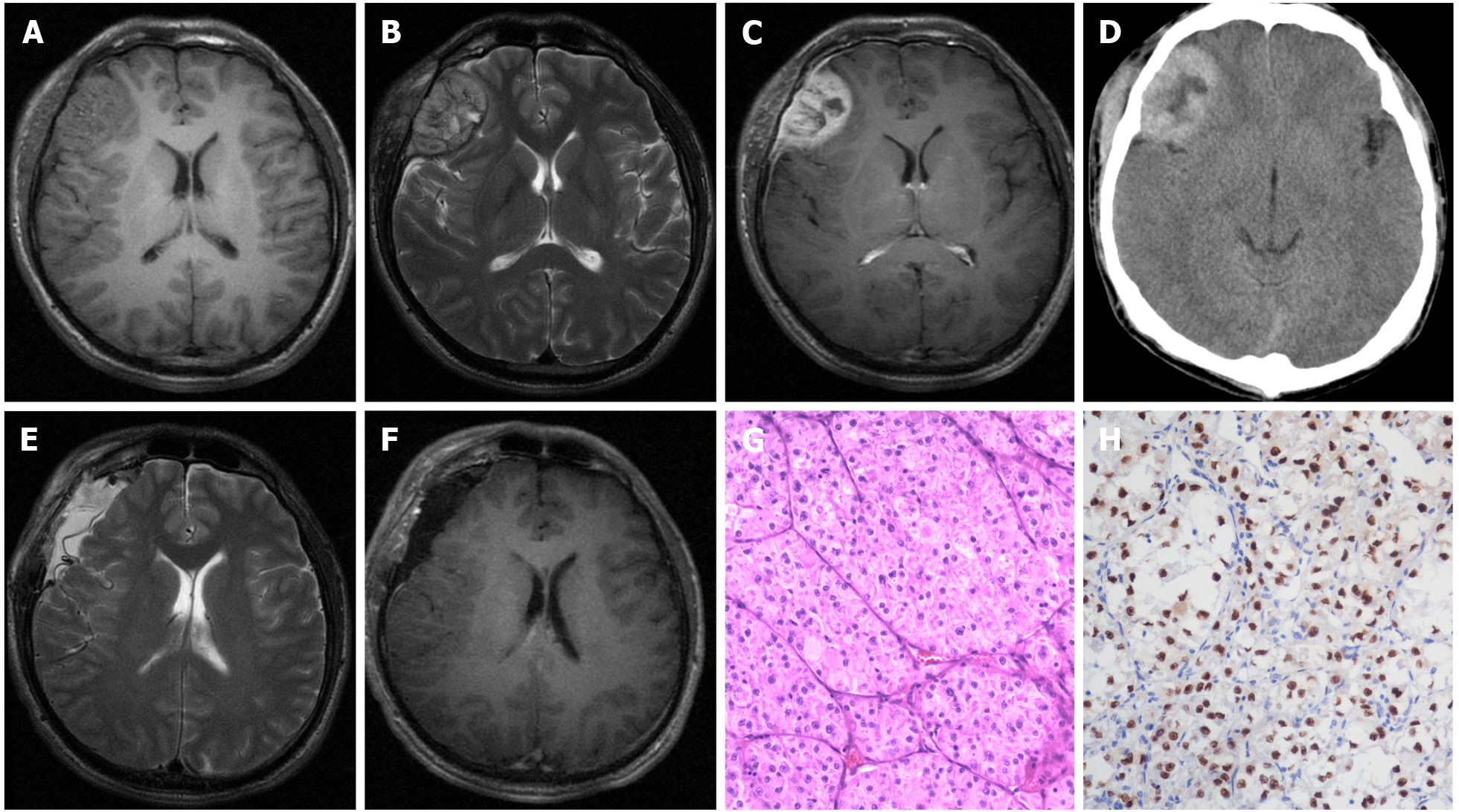

Pre-operative chest X-ray scans were normal in all patients. CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging were performed in all patients. The majority of lesions (4/5) presented as isointense/hypointense on T1 images, isointense/hyperintense on T2 images, and heterogeneous enhancement after the administration of gadolinium, with a heterogeneously high-density appearance on CT scan (Figure 1A-D). The median tumor size was 3.0 cm (range: 2.8-5.0 cm). Anterior skull-base ASPS was found in 1 case; the other 4 ASPSs were frontal, parietal, parieto-occipital, and temporal.

Multidisciplinary expert consultations were recorded for all patients, and one of them (the 10th case in Table 1) was presented in this part.

The radiological appearance of this patient was not typical. Meningioma could be one potential diagnosis.

Based on symptoms, signs, physical examinations, and radiological scans, a presumed diagnosis was right frontal meningioma. Surgical treatment should be planned to remove the brain tumor and obtain a pathological diagnosis.

Craniotomy should be performed via the right frontal approach.

Under the microscope, the specimens from hematoxylin-eosin staining showed a characteristic appearance of nests of cells loosely arranged along fibrous septa. Immunohistochemistry staining revealed tumor cells were positive for TEF-3. Pathological findings were consistent with the diagnosis of ASPS.

Positron emission tomography or combinations of x-ray chest film, abdominal ultrasound scan, and/or CT should be performed to evaluate extracranial lesions. The diagnosis of PIASPS was only made when there was no evidence of extracranial ASPS.

After a pathological diagnosis was established, further diagnostic work-up was conducted when necessary. The final diagnoses of the 5 patients were PIASPS.

None of these patients was treated outside regarding the intracranial lesion. All of these patients accepted surgical treatments. In addition to routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 1G), immunohistochemical examination for TFE-3 was also employed (Figure 1H). Before establishing the diagnosis of PIASPS, extensive screenings were performed to exclude potential extracranial lesions, which included but were not limited to CT chest, abdomen and pelvis, and positron emission tomography.

Postoperatively, gross total resection (GTR) and NGTR were achieved in 3 and 2 patients, respectively. Among the patients who received GTR, 1 patient received no adjuvant therapies and another 2 patients accepted local radiation therapy because of a high Ki-67 index (> 10%). Both NGTR patients received radiotherapy. Consequently, 4 patients received adjuvant radiotherapy postoperatively. The radiation doses available in three patients were 42 Grays, 46 Grays, and 52 Grays. Only 1 patient received chemotherapy (doxorubicin and ifosfamide), which followed NGTR plus radiotherapy.

After a median follow-up of 36 mo (range: 25-61 mo), 1 patient remained tumor-free, but tumor progression was noticed in 4 patients. Local recurrence (LR) was observed in 3 patients, and the durations for LR were 8 mo, 10 mo, and 15 mo. All three patients with LR received surgical treatment, with one receiving radiotherapy and chemotherapy after surgery. Another patient suffered from leptomeningeal metastases, and the patient declined further treatments. When this study ended, 3 patients died of the disease (20 mo, 50 mo, and 61 mo after surgery).

An extensive search using the medical subject heading term "alveolar soft-part sarcoma" was conducted in OVID MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database, and PubMed. Published cases were included as long as candidates were pathologically diagnosed with PIASPS and reported in the English literature. Cases with the concurrent presence of IASPS and other malignant tumors were excluded. Chen JY and Zhang FC scrutinized the resources of each patient to rule out duplicate cases. The clinical data of interest included the following: Age at diagnosis, sex, tumor location, the extent of surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). Statistical analyses of the role of treatment options in prognoses (PFS and OS) were assessed by the Log-rank test using STATA 15.0 (Stata Corp, Lakeway Drive College Station, TX, United States). When P-value < 0.05, the difference is considered significant statistically.

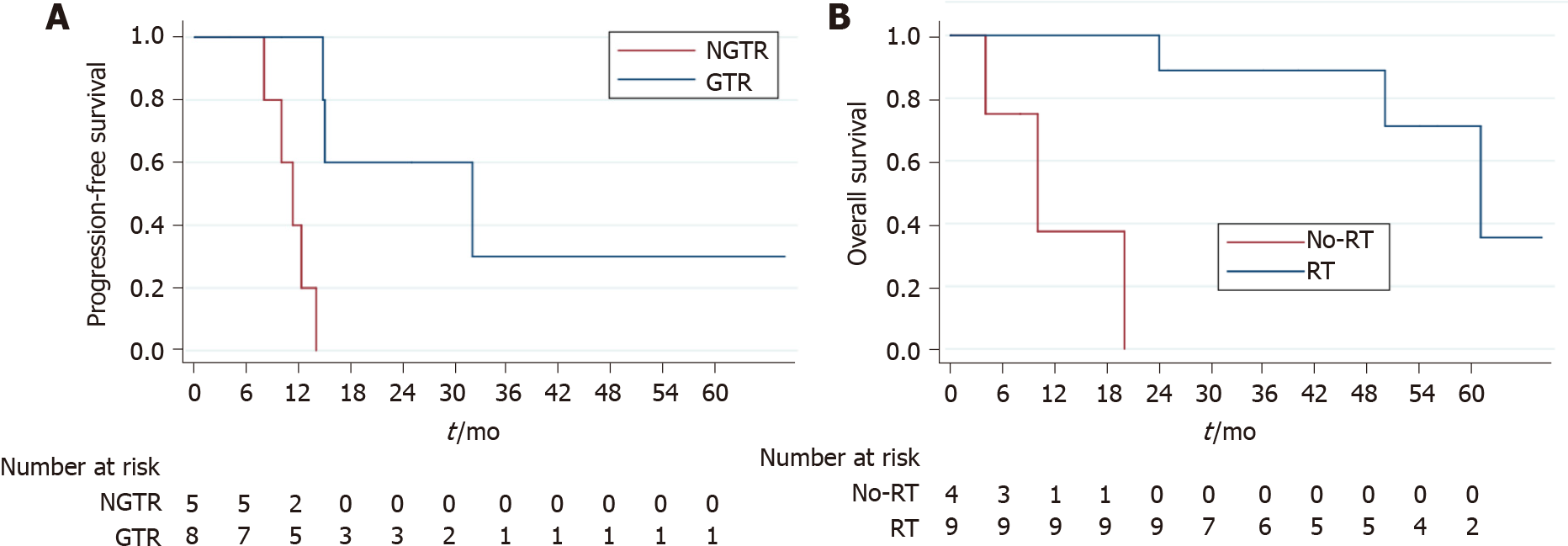

To investigate this disease comprehensively, the cases from our center and previous studies were pooled to conduct survival analyses. In brief, the female predominance was confirmed, as the integrated data (n = 14) 5 males and 9 females (Table 1). The median age of 14 patients was 19 years, ranging from 8 to 53 years. One patient's follow-up detail was not reported[11]; the other 13 patients were available regarding follow-up data, with a median follow-up being 36 mo (range: 4-68 mo). Tumor progression was found in 8 (61.5%) cases and death due to disease was observed in 4 (30.4%) cases. The 3-year PFS and OS were 15.5% and 67.1%, respectively. According to log-rank tests, GTR (3-year PFS of GTR vs NGTR was 36.0% vs 0; P = 0.011) (Figure 2A) could prolong PFS but not the use of radiotherapy (P = 0.128) or chemotherapy (P = 0.090). Only radiotherapy (3-year OS of radiotherapy vs no radiotherapy was 87.5% vs 0; P < 0.001) (Figure 2B) resulted in longer OS, and neither GTR (P = 0.071) nor chemotherapy (P = 0.064) did.

ASPS is a rare tumor with a slow high metastatic rate. Prior research has shown that GPNMB (glycoprotein nmb), a transcriptional target of ASPSCR1-TFE3, might exert a critical role during its systemic metastasis[16]. The brain is one of the most vulnerable sites of metastases[7]. Accounting for the terminal event and primary reason for death among patients with ASPS[8,12], brain metastasis reportedly features an incidence of 11%-21%[1,6,17,18]. However, the incidence of PIASPS is less common. In addition to the 5 cases treated at our institute, only 9 cases with PIASPA were reported[3,9-15]. Our findings based on pooled cases revealed that PIASPS affected young adults with female predominance; GTR (PFS) and the use of radiotherapy (OS) contributed to better prognoses.

Surgical resection remains the mainstay of the treatment for IASPS[19-21]. Indeed, we found that GTR subgroup achieved a higher 3-year PFS rate when compared with the NGTR in this study. Meanwhile, there was a report[22] stating that surgery was not only associated with improved survival but also with better neurological outcomes. All accessible lesions should be completely removed to achieve better outcomes[19], and staged surgeries have been performed to accomplish this goal[21]. However, statistical analyses failed to prove that GTR could improve the OS in this study, which could be attributed to the relatively small cohort size.

ASPS reportedly responded to radiotherapy, and several authors insisted that on the postoperative administration of radiotherapy to patients with insufficient surgical margins or even as a routine schedule[9,12,15]. Interestingly, when GTR was achieved, some centers still recommended adjuvant radiotherapy[13,15], while other centers did not[3,11,14]. Based on our experience, those patients with a high Ki-67 index or incomplete tumor resection were suitable for radiotherapy. While it was seemingly impossible to evaluate the role of radiotherapy in PIASPS based on previous case reports, pooling cases together indicated that radiotherapy could significantly improve OS. Only 6 cases reported radiation doses in the pooled cohort, which precluded further evaluation of increasing radiation doses' efficacy and safety in treating PFS. Unfortunately, our analyses failed to demonstrate that radiotherapy enabled significantly to prolong PFS. Future studies on optimal radiation modalities, radiation doses, and the optimal radiotherapy administration time are warranted to improve the efficacy of radiotherapy.

Anthracycline- or ifosfamide-based regimens, which were considered effective in treating other soft tissue sarcomas, lacked efficacy in resolving ASPS[7]. Only 3 patients were administrated with chemotherapy in the pooled cohort (Table 1)[10,13]. Consequently, our results failed to find evidence for the efficacy of chemotherapy, in prolonging either PFS or OS. Novel agents, including vascular endothelial growth factor-predominant tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., pazopanib[5]) and the mesen

The results based on the pooled data should be carefully interpreted, as they were from various centers and distributed among the past 3 decades. However, we tried our best to minimize the bias by retrieving the objective parameters. Finally, this study, to the best of our knowledge, firstly assessed the PFS and OS of patients with PIASPS and the role of treatment options in improving patients' prognoses with PIASPS.

PIASPS is a rare malignancy and predominately affects young females. Patients with PIASPS suffer from poor outcomes, characterized by a high tendency of recurrence. Surgical treatment is the first choice, and GTR should be achieved when the tumor is feasible. Patients with PIASPS benefit from radiotherapy, which should be considered as a part of treatment therapies. Future studies are needed to investigate effective radiation modalities and novel agents.

We appreciated Prof. Jia Wang (Department of Neurosurgery, General Hospital of the Yangtze River Shipping) and Jing Lv (Department of Pathology, General Hospital of the Yangtze River Shipping) for their contributions in multidisciplinary expert consultation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ottaviano M S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu M

| 1. | Paoluzzi L, Maki RG. Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment of Alveolar Soft-Part Sarcoma: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:254-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Christopherson WM, Foote FW Jr, Stewart FW. Alveolar soft-part sarcomas; structurally characteristic tumors of uncertain histogenesis. Cancer. 1952;5:100-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bodi I, Gonzalez D, Epaliyange P, Gullan R, Fisher C. Meningeal alveolar soft part sarcoma confirmed by characteristic ASPCR1-TFE3 fusion. Neuropathology. 2009;29:460-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Heimann P, Devalck C, Debusscher C, Sariban E, Vamos E. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma: further evidence by FISH for the involvement of chromosome band 17q25. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998;23:194-197. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Schöffski P, Wozniak A, Kasper B, Aamdal S, Leahy MG, Rutkowski P, Bauer S, Gelderblom H, Italiano A, Lindner LH, Hennig I, Strauss S, Zakotnik B, Anthoney A, Albiges L, Blay JY, Reichardt P, Sufliarsky J, van der Graaf WTA, Debiec-Rychter M, Sciot R, Van Cann T, Marréaud S, Raveloarivahy T, Collette S, Stacchiotti S. Activity and safety of crizotinib in patients with alveolar soft part sarcoma with rearrangement of TFE3: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) phase II trial 90101 'CREATE'. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:758-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Portera CA Jr, Ho V, Patel SR, Hunt KK, Feig BW, Respondek PM, Yasko AW, Benjamin RS, Pollock RE, Pisters PW. Alveolar soft part sarcoma: clinical course and patterns of metastasis in 70 patients treated at a single institution. Cancer 2001; 91:585-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Reichardt P, Lindner T, Pink D, Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Dörken B. Chemotherapy in alveolar soft part sarcomas. What do we know? Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1511-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lieberman PH, Foote FW Jr, Stewart FW, Berg JW. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma. JAMA. 1966;198:1047-1051. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Bots GT, Tijssen CC, Wijnalda D, Teepen JL. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the pituitary gland with secondary involvement of the right cerebral ventricle. Br J Neurosurg. 1988;2:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Das KK, Singh RK, Jaiswal S, Agrawal V, Jaiswal AK, Behari S. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the frontal calvarium and adjacent frontal lobe. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2012;7:36-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mandal S, Majumdar K, Kumar Saran R, Jagetia A. Meningeal alveolar soft part sarcoma masquerading as a meningioma: a case report. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:693-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ahn SH, Lee JY, Wang KC, Park SH, Cheon JE, Phi JH, Kim SK. Primary alveolar soft part sarcoma arising from the cerebellopontine angle. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30:345-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Emmez H, Kale A, Sevinç Ç, Börcek AÖ, Yilmaz G, Kaymaz M, Uluoğlu Ö, Paşaoğlu A. Primary Intracerebral Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma in an 11-Year-Old Girl: Case Report and Review of the Literature. NMC Case Rep J. 2015;2:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kumar A, Alrohmain B, Taylor W, Bhattathiri P. Alveolar soft part sarcoma: the new primary intracranial malignancy : A case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2019;42:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tao X, Tian R, Hao S, Li H, Gao Z, Liu B. Primary Intracranial Alveolar Soft-Part Sarcoma: Report of Two Cases and a Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2016;90:699.e1-699.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tanaka M, Homme M, Yamazaki Y, Shimizu R, Takazawa Y, Nakamura T. Modeling Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma Unveils Novel Mechanisms of Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2017;77:897-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang CH, Lee N, Lee LS. Successful treatment for solitary brain metastasis from alveolar soft part sarcoma. J Neurooncol. 1995;25:161-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Flores RJ, Harrison DJ, Federman NC, Furman WL, Huh WW, Broaddus EG, Okcu MF, Venkatramani R. Alveolar soft part sarcoma in children and young adults: A report of 69 cases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65:e26953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tao X, Hou Z, Wu Z, Hao S, Liu B. Brain metastatic alveolar soft-part sarcoma: Clinicopathological profiles, management and outcomes. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:5779-5784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Perry JR, Bilbao JM. Metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma presenting as a dural-based cerebral mass. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:168-170. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Bindal RK, Sawaya RE, Leavens ME, Taylor SH, Guinee VF. Sarcoma metastatic to the brain: results of surgical treatment. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:185-90; discussion 190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fox BD, Patel A, Suki D, Rao G. Surgical management of metastatic sarcoma to the brain. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:181-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lewin J, Davidson S, Anderson ND, Lau BY, Kelly J, Tabori U, Salah S, Butler MO, Aung KL, Shlien A, Dickson BC, Abdul Razak AR. Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Two Patients with Alveolar Soft-Part Sarcoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:1001-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Conley AP, Trinh VA, Zobniw CM, Posey K, Martinez JD, Arrieta OG, Wang WL, Lazar AJ, Somaiah N, Roszik J, Patel SR. Positive Tumor Response to Combined Checkpoint Inhibitors in a Patient With Refractory Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma: A Case Report. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Su H, Yu C, Ma X, Song Q. Combined immunotherapy and targeted treatment for primary alveolar soft part sarcoma of the lung: case report and literature review. Invest New Drugs. 2021;39:1411-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wen PY, Weller M, Lee EQ, Alexander BM, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Barthel FP, Batchelor TT, Bindra RS, Chang SM, Chiocca EA, Cloughesy TF, DeGroot JF, Galanis E, Gilbert MR, Hegi ME, Horbinski C, Huang RY, Lassman AB, Le Rhun E, Lim M, Mehta MP, Mellinghoff IK, Minniti G, Nathanson D, Platten M, Preusser M, Roth P, Sanson M, Schiff D, Short SC, Taphoorn MJB, Tonn JC, Tsang J, Verhaak RGW, von Deimling A, Wick W, Zadeh G, Reardon DA, Aldape KD, van den Bent MJ. Glioblastoma in adults: a Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and European Society of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) consensus review on current management and future directions. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22:1073-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 146.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |