Published online Jun 16, 2013. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i3.128

Revised: April 19, 2013

Accepted: May 8, 2013

Published online: June 16, 2013

Processing time: 106 Days and 0.1 Hours

Peripheral cemento-ossifying fibroma (PCOF) is a rare osteogenic neoplasm that ordinarily presents as an epulis-like growth. This is of a reactive rather than neoplastic nature and its pathogenesis is uncertain. PCOF predominantly affects adolescent and young adults with greatest prevalence around 28 years. We report here a rare clinical case of PCOF of the mandible, 1 cm mesiodistally and 1.5 cm occluso-gingivally in diameter, which caused difficulty in eating and speech, in a 42-year-old female patient. She was asymptomatic for 1 year and on follow-up for 6 mo post surgically showed gingival health and normal radioopacity of bone without any recurrence. Clinical, radiographic and histological characteristics are discussed and recommendations regarding differential diagnosis, treatment and follow up are provided. The controversial varied nomenclature and possible etiopathogenesis of PCOF are emphasized.

Core tip: The cemento-ossifying fibroma is a central neoplasm of bone as well as periodontium. The pathogenesis of this tumor is uncertain. Due to their clinical and histopathological similarities, some peripheral cemento ossifying fibromas (PCOFs) are believed to show fibrous maturation and subsequent calcification. The diagnosis of PCOF based only on clinical observation is difficult, hence radiographs and histopathological examination are essential for accurate diagnosis. In addition, a complete excision of the lesion is required to prevent reoccurrence.

- Citation: Mishra AK, Maru R, Dhodapkar SV, Jaiswal G, Kumar R, Punjabi H. Peripheral cemento-ossifying fibroma: A case report with review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2013; 1(3): 128-133

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v1/i3/128.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v1.i3.128

Many types of localized reactive lesions may occur on the gingiva, including focal fibrous hyperplasia, pyogenic granuloma, peripheral giant cell granuloma and peripheralcemento-ossifying fibroma[1]. These lesions may arise as a result of irritants such as trauma, microorganisms, plaque, calculus, dental restorations and dental appliances[2,3]

The 1992 World Health Organization classification groups under a single designation (cemento-ossifying fibroma) two histologic types (cementifying fibroma and ossifying fibroma) that may be clinically and radiographically indistinguishable[4].

Peripheral cemento-ossifying fibroma (PCOF) is a relatively rare lesion with variable forms. It is defined as a well demarcated and occasionally encapsulated lesion consisting of fibrous tissue which contains variable amounts of mineralized material resembling bone (ossifying fibroma), cementum (cementofying fibroma) or both[5,6].

PCOF usually follows a salient clinical course, except in the case of lesions affecting gingiva which present as an enlarging mass that grows progressively, finally producing a facial deformity. The pathogenesis of this lesion is uncertain and it is thought to arise from the periosteal and periodontal membrane[7]. Because of the close proximity and similarity to the periodontal tissue, the term periodontoma sometimes is applied[8]. There is however no proof to support this connection and their occurrence in areas distant from periodontal ligament remains unexplained[9].

PCOF accounts for 3.1% of all oral tumors and 9.6% of gingival lesions[10]. It may occur at any age but exhibits a peak incidence between the second and third decades. The average age is around 28 years with females being affected more than males[11]. Female predilection has been reported to be as high as 5:112[12,13]. Clinically PCOFs are sessile or pedunculated, usually ulcerated and erythematous or exhibit a color similar to that of surrounding gingiva[14,15]. These lesions are generally < 2 cm in size although lesions larger than 10 cm are occasionally observed. About 60% of the tumors occur in the maxilla and more than 50% of all cases affect the region of the incisors and canines. A potential for tooth migration due to the presence of PCOF has been reported[15-17]. In the vast majority of cases, there is no apparent underlying bone involvement visible on roentgenograms. However on rare occasions, there appears to be superficial erosion of bone[16,17].

PCOF should be surgically excised and submitted to microscopic examination for confirmation of diagnosis. The extraction of adjacent teeth is seldom necessary or justified. Recurrences are uncommon but have been described[2]. There have, however, been few reports on this rare lesion. A case of PCOF in the mandibular gingiva of a 42-year-old female patient is described here. In this age group and in the mandibular anterior quadrant, PCOF is rare and has not previously been reported in the literature.

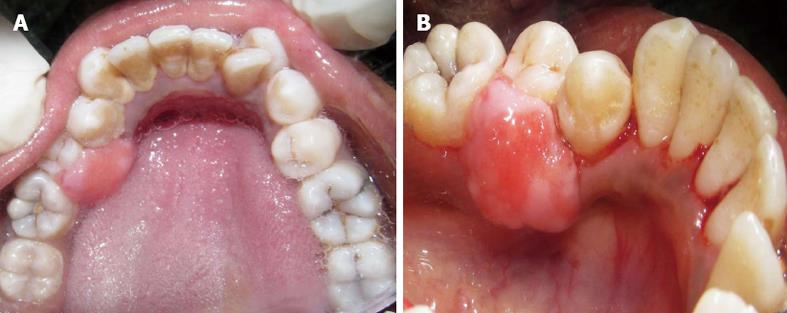

A 42-year-old female patient presented at the outpatient Department of Periodontics, Sri Aurobindo Institute of Dentistry and Post Graduate Institute Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India with the chief complaint of gum swelling in the lower right back tooth region (Figure 1). The swelling had been present for 1 year and had been slowly increasing in volume over that time. Occasionally bleeding occurred when the patient brushed her teeth and was associated with slight pain. She denied tobacco and alcohol use. The patient’s past dental and medical histories were unremarkable.

Extraoral examination showed facial symmetry and the overlying skin showed no signs of inflammation. The regional lymph nodes were palpable but were not enlarged or tender.

Intraoral examination revealed a solitary, diffuse, non-tender pinkish-red growth of approximately 1 cm × 1.5 cm, confined to the lingual gingiva in the mandibular II premolar region. The lesion was neither fluctuant nor did it blanch with digital pressure, and had firm consistency. The labial gingiva was not involved. The local irritants, plaque and calculus were abundant in the 44, 45 region.

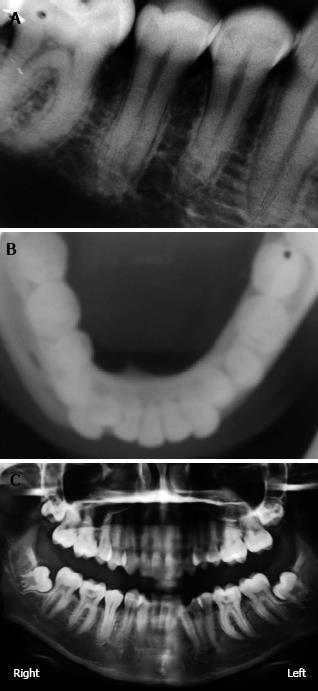

Intraoral periapical, occlusal and ortho pantomo roentgenograms were obtained. The radiographic examination showed no signs of involvement of the alveolar ridge (Figure 2).

The patient underwent complete blood investigation prior to the surgery and all readings, including hemoglobin, bleeding time, clotting time, total and differential leukocyte counts were within normal limits. The patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus and Australian antigen (hepatitis B surface antigen).

Provisional diagnosis of PCOF was made. Clinically, the differential diagnosis included pyogenic granuloma, fibrous hyperplasia, peripheral ossifying fibroma and peripheralgiant cell granuloma.

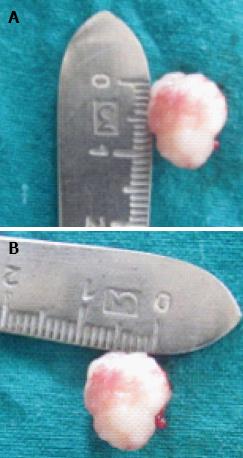

Since the gingival growth was diffuse, surgical removal by internal bevel gingivectomy was chosen. Under local anaesthesia containing xylocaine with adrenaline 1:80000 concentration, the initial scalloped internal bevel incision was made with a 15 No. BP blade at a point far apical to the growth. While making this incision, care was taken to preserve as much attached gingiva as possible apical to the lesion. A second crevicular incision was made with a 12 No. BP blade at the base of the pseudopocket, until it met the first internal bevel incision. To split the labial and palatal, a third interdental incision was made with a 11 No. BP blade in the adjacent interproximal areas tissue. Only the lingual mucoperiosteal flap was reflected with periosteal elevators until the apical end of internal bevel incision was visible. The three incisions completely removed the gingival growth which measured 1 cm × 1.5 cm (Figure 3). The tissue removed was submitted for histopathological examination. Adjacent teeth were scaled to remove local irritants. Underlying bone was curetted to remove periodontal ligaments and periosteum. The flap was inspected for any tissue tags and sutured with interdental interrupted non-resorbable 3-0 silk sutures (Figure 4). Non-eugenol coe-pack was applied both lingualy and labially. The patient was discharged with post-operative instructions and told to come-back after 7 d for suture removal. The patient was given cap. amoxicillin 500 mg every 8 h, beginning 1 d before the operation and continued for a 5-d postoperative period, and 500 mg of acetaminophen three times daily for 5 d along with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate for rinsing twice daily until proper plaque control technique could be resumed.

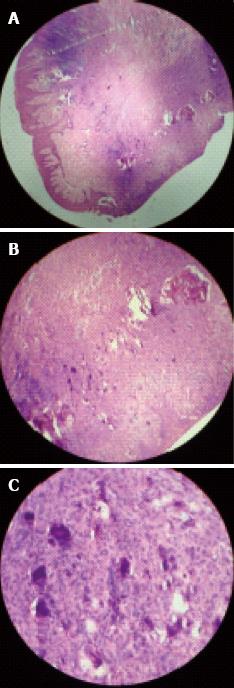

The microscopic examination of the excised tissue revealed a parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with long and slender rete ridges. Underlying connective tissue was fibrocellular, comprising collagen fibers. The connective tissue contained a few round to ovoid cementum-like calcified blood vessels, fibroblasts and dense inflammatory cell infiltrate. Deeper areas showed highly cellular connective tissue comprising plump cells with oval nuclei surrounding small globular areas of calcification, resembling cementoids. In some areas bone trabeculae with osteocytes and osteoblastic rimming was also seen. The features were suggestive of “PCOF” (Figure 5).

The patient presented for follow-up examination 7 d post operatively. The coe-pack and the sutures were removed and the operated area was irrigated with normal saline. The surgical site appeared to be healing well and there was no need to repack the site. At one month postoperatively the surgical site had healed completely, the flap was well adapted to the underlying bone with physiologically scalloped contours and thin knife-edge margins (Figure 6). There was no evidence of recurrence of the lesion at 6 mo and the patient was asymptomatic.

PCOFs have been described in the literature since the 1940s. Many names have been given to similar lesions such as epulis[1], peripheral fibroma with calcifications[2], peripheral ossifying fibroma[2,3] calcifying fibroblastic granuloma[18], peripheral cemetifying fibroma[3], peripheral fibroma with cementogenesis[19], and peripheral cemento ossifying firoma[20]. The sheer number of names used for fibroblastic calcifying gingival lesions indicates that there is much controversy surrounding their classification[19].

The basis of benign fibro-osseus lesions was established by Wladron[5]. They are divided into three main categories: fibrous dysplasia, reactive lesions (periapial cemento-osseus dysplasia, focal cemento-osseus dysplasia and florid cementoosseus dysplasia) and fibro-osseus neoplasms. PCOF is actually considered as a fibro-osseus dysplasia and has been included in the group of non odontogenic tumours since the 1992 WHO classification[5,6]

Alt hough the etiopathogenesis of PCOF is uncertain, an origin from cells of the periodontal ligament has been suggested[20]. The reasons for considering a periodontal origin for PCOF include the exclusive occurrence of PCOF in the gingiva, the proximity of gingiva to the periodontal ligament and the presence of oxytalan fibers within the mineralized matrix of same lesions[19]. Excessive proliferation of mature fibrous connective tissue is a response to gingival injury, gingival irritation, subgingival calculus or a foreign body in the gingival sulcus. Chronic irritation of the periosteal and periodontal membrane causes metaplasia of the connective tissue and resultant irritation of bone formation or dystrophic calcification. It has been suggested that the lesion may be caused by fibrosis of the granulation tissue[7]. The clinical evolution of tumors is usually as follows. Initially asymptomatic, the tumor progressively grows to the point where its size causes pain as well as functional alteration and cosmetic deformities[1,6]. This was observed in our patient who presented with an enlarged mass accompanied by slight pain and cosmetic deformity. Cases of tooth migration and bone destruction have been reported, but these are not common[15,21]. In the present case the lesion was pink, firm, slightly tender on palpation with a smooth non-ulcerated surface and a broad attachment base. The dimensions were 1 cm × 1.5 cm, well within the expected range. Although the majority of lesions occur in the second decade of life[12], this female patient was 42-year-old with the lesion occurring in mandibular right premolar region[11,14,22].

Hormonal influences may play a role, given the higher incidence of PCOF among females, the increasing occurrence in the second decade and declining incidence after the third decade[16]. In an isolated case of multicentric PCOF, Kumar et al[19] noted the presence of a lesion at an edentulous site in a 49-year-old women which gives rise to further questions regarding the pathogenesis of this types of lesion. The same type of lesion at a dentulous site in a 50-year-old female was documented by Mishra et al[23].

Radiographically, PCOF may follow different patterns depending on the amount of mineralized tissue[4-6]. Radio-opaque foci of calcification have been reported to be scattered throughthe central area of the lesion but not all lesions demonstrate radiographic calcifications[7].

Underlying bone involvement is usually not visible on radiographs. In rare instances superficial erosion of bone is noted[7]. In the present case no radiographic changes were found, indicating that this could be an early stage lesion. Frequently, PCOF shows similar clinical features to other extraosseous lesions. It may be misdiagnosed as pyogenic ganuloma, fibrous dysplasia, peripheral giant cell granuloma, osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, low grade osteosarcoma, cementoblastoma, chronic osteomyelitis and sclerosing osteomyelitis of Garre[4-6]. In general the pyogenic granuloma presents as a red soft friable nodule that bleeds with minimal manipulation but tooth displacement and resorption of alveolar bone are not observed. Although peripheral giant cell granuloma has features similar to those of PCOF, the latter lacks the blue discoloration commonly associated with peripheral giant cell granuloma and shows flakes of calcification, radiographically as well histologically. Thus, the diagnosis of PCOF based only on clinical observations can be difficult and histopathological examination of the surgical specimen obtained by excisional biopsy is essential for an accurate diagnosis. All the classic histopathological features of PCOF were present in this case. The preferred treatment is surgical, consisting of resection of the lesion as well as curettage of its osseous floor (Periodontal ligament and Periosteum) and scaling of adjacent teeth, as was performed in this case. Recovery was uneventful and the patient has remained tumor free for 24 wk. Because this lesion is poorly vascularized and well circumscribed, it is easily removed from the surrounding bone. This is one of the main differences with fibrous dysplasia[5,6].

Prognosis is excellent and recurrence is rare if correctly managed[4,5]. The recurrence rate of PCOF is high for reactive lesions[11,16] and recurrence is probably due to incomplete removal of the lesion, repeated injury or persistence of local irritants[16]. The rate of recurrence has been reported at 8.9%[1], 9%[21], 14%[16], 16%[11] and 20%[2]. Therefore the patient is still on a regular schedule of follow up.

In conclusion, PCOF is a slowly progressive lesion generally with limited growth. Many cases will progress for long periods before the patient seeks treatment because of the lack of symptoms associated with the lesion. A slowly growing pink soft tissue nodule in the anterior maxilla of an adolescent should raise suspicion of PCOF. Since the diagnosis of PCOF based only on clinical features is very difficult, radiographs and histopathological examination are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Treatment consists of surgical excision including periodontal ligament periosteum and scaling of adjacent teeth. Close postoperative follow-up is required because of the growth potential for incompletely removed lesions and the 8%-20% recurrence rate.

P- Reviewers Ghimire LV, Ishiguro T, Ozkan OV, Shipman A S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Bhaskar SN, Jacoway JR. Peripheral fibroma and peripheral fibroma with calcification: report of 376 cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1966;73:1312-1320. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Eversole LR, Rovin S. Reactive lesions of the gingiva. J Oral Pathol. 1972;1:30-38. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Gardner DG. The peripheral odontogenic fibroma: an attempt at clarification. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:40-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Martín-Granizo R, Sanchez-Cuellar A, Falahat F. Cemento-ossifying fibroma of the upper gingivae. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Waldron CA. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:828-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | De Vicente Rodríguez JC, González Méndez S, Santamaría Zuazua J, Rubiales B. Tumores no odontogénicos de los maxilares: clasificación,clínicay diagnóstico. Med Oral. 1997;12:83-93. |

| 7. | Kendrick F, Waggoner WF. Managing a peripheral ossifying fibroma. ASDC J Dent Child. 1996;63:135-138. [PubMed] |

| 8. | El-Mofty SK. Cemento-ossifying fibroma and benign cementoblastoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1999;16:302-307. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Vlachou S, Terzakis G, Doundoulakis G, Barbati C, Papazoglou G. Ossifying fibroma of the temporal bone. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:654-656. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Delbem ACB, Cunha RF, Silva JZ, Pires AM. Soubhiac Peripheral Cemento-Ossifying Fibroma in Child. A Follow-Up of 4 Years. Report of a Case. Eur J Dent. 2008;2:134-137. |

| 11. | Buchner A, Hansen LS. The histomorphologic spectrum of peripheral ossifying fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:452-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Eversole LR, Leider AS, Nelson K. Ossifying fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of sixty-four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60:505-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jung SL, Choi KH, Park YH, Song HC, Kwon MS. Cemento-ossifying fibroma presenting as a mass of the parapharyngeal and masticator space. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1744-1746. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bodner L, Dayan D. Growth potential of peripheral ossifying fibroma. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:551-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Poon CK, Kwan PC, Chao SY. Giant peripheral ossifying fibroma of the maxilla: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:695-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kenney JN, Kaugars GE, Abbey LM. Comparison between the peripheral ossifying fibroma and peripheral odontogenic fibroma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:378-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mesquita RA, Orsini SC, Sousa M, de Araújo NS. Proliferative activity in peripheral ossifying fibroma and ossifying fibroma. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:64-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee KW. The fibrous epulis and related lesions. Granuloma pyogenicum, ‘Pregnancy tumour’, fibro-epithelial polyp and calcifying fibroblastic granuloma. A clinico-pathological study. Periodontics. 1968;6:277-292. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kumar SK, Ram S, Jorgensen MG, Shuler CF, Sedghizadeh PP. Multicentric peripheral ossifying fibroma. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:239-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Feller L, Buskin A, Raubenheimer EJ. Cemento-ossifying fibroma: case report and review of the literature. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2004;6:131-135. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Cuisia ZE, Brannon RB. Peripheral ossifying fibroma--a clinical evaluation of 134 pediatric cases. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23:245-248. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: (Elsevier) WB Saunders Co 2002; 451–452. |

| 23. | Mishra AK, Bhusari P, Kanteshwari K. Peripheral cemento-ossifying fibroma--a case report. Int J Dent Hyg. 2011;9:234-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |