Published online Feb 19, 2022. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i2.323

Peer-review started: April 23, 2021

First decision: June 17, 2021

Revised: June 30, 2021

Accepted: December 25, 2021

Article in press: December 25, 2021

Published online: February 19, 2022

Processing time: 299 Days and 22.3 Hours

Healthcare professionals need to be prepared to promote healthy lifestyles and care for patients. By focusing on what students should be able to perform one day as clinicians, we can bridge the gap between mere theoretical knowledge and its practical application. Gender aspects in clinical medicine also have to be considered when speaking of personalized medicine and learning curricula.

To determine sets of intellectual, personal, social, and emotional abilities that comprise core qualifications in medicine for performing well in anamnesis-taking, in order to identify training needs.

An analysis of training clinicians’ conceptions with respect to optimal medical history taking was performed. The chosen study design also aimed to assess gender effects. Structured interviews with supervising clinicians were carried out in a descriptive study at the Medical University of Vienna. Results were analyzed by conducting a qualitative computer-assisted content analysis of the interviews. Inductive category formation was applied. The main questions posed to the supervisors dealt with (1) Observed competencies of students in medical history taking; and (2) The supervisor’s own conceptions of "ideal medical history taking".

A total of 33 training clinicians (n = 33), engaged in supervising medical students according to the MedUni Vienna’s curriculum standards, agreed to be enrolled in the study and met inclusion criteria. The qualitative content analysis revealed the following themes relevant to taking an anamnesis: (1) Knowledge; (2) Soft skills (relationship-building abilities, trust, and attitude); (3) Methodical skills (structuring, precision, and completeness of information gathering); and (4) Environmental/contextual factors (language barrier, time pressure, interruptions). Overall, health care professionals consider empathy and attitude as critical features concerning the quality of medical history taking. When looking at physicians’ theoretical conceptions, more general practitioners and psychiatrists mentioned attitude and empathy in the context of "ideal medical history taking", with a higher percentage of females. With respect to observations of students’ history taking, a positive impact from attitude and empathy was mainly described by male health care professionals, whereas no predominance of specialty was found. Representatives of general medicine and internal medicine, when observing medical students, more often emphasized a negative impact on history taking when students lacked attitude or showed non-empathetic behavior; no gender-specific difference was detected for this finding.

The analysis reveals that for clinicians engaged in medical student education, only a combination of skills, including adequate knowledge and methodical implementations, is supposed to guarantee acceptable performance. This study’s findings support the importance of concepts like relationship building, attitude, and empathy. However, there may be contextual factors in play as well, and transference of theoretical concepts into the clinical setting might prove challenging.

Core Tip: The findings in this study underline the importance of paying attention to core competencies in medicine and medical students’ socialization and training. Enriching self-assessments with observer-based reflections, as carried out in this investigation, seems to be a valid approach to identify training needs. Tolerance of ambiguity and openness to self-reflection, as demonstrated by the participants in our study, might be relevant in this context. Empathic relationships shape embodied empathy, result in embodied skills, and shift an individual’s perception.

- Citation: Steinmair D, Zervos K, Wong G, Löffler-Stastka H. Importance of communication in medical practice and medical education: An emphasis on empathy and attitudes and their possible influences. World J Psychiatry 2022; 12(2): 323-337

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v12/i2/323.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i2.323

Freud’s advice for physicians practicing psychoanalysis was to not concentrate on details and rather surrender one’s attention- the optimal mental state of an analyst: “withhold all conscious influences from his/her capacity to attend, and give himself/herself over completely to his/her ‘unconscious memory’”[1].

This attitude differs a great deal from most clinical settings nowadays, due to necessary domain-based medical skills. The rapid medical technology developments in the last decade (e.g., digital innovations like remote monitoring/mobile apps, medical devices, and robotic systems/machines controlled by a doctor and mixed reality in education) shape all healthcare fields. Nevertheless, as medicine is practiced for and by human beings, human factors are predominant in all interactions. To infer the workings of a patient’s mind is a challenging task, and accepting uncertainty and incompleteness of our understanding is an unavoidable recognition[1,2]. Thus, personal and interpersonal competencies are relevant in meeting the needs of the health system, together with expert knowledge and skills[3].

Interpersonal skills are especially relevant when taking a patient’s history[4]. Guidelines for general medical history taking skills usually include a semi-structured interview manual that suggests a structured approach, in order to ensure professionalism[5,6]. In addition, communication components, such as relationship-building, trust, and respect, are established as markers for quality care[4]. The level of evidence supporting methods of developing these abilities, as well as medical professionalism, is limited[7,8]. Frameworks for communication-oriented curricula have been developed because the importance of building a relationship was found to be one of the core competencies in the physician-patient interaction[9-13].

An essential concept with a great impact on the quality of communication and professionalism is empathy. Empathy has been shown to be trainable but might depend on personality[14-18]. Through empathy, it is possible to improve the patients’ compliance, satisfaction, clinical outcome, and decrease (interestingly enough) the possibility of a lawsuit[17-26]. Empathy describes a semi-voluntary, and in some conceptualizations, innate ability to share affective states with others, and requires a certain curiosity. Definitions of empathy overlap with another important concept, that of mentalization. Mentalizing (Theory of Mind) is the ability to interpret one’s own and others’’ mental states (i.e. intentions, beliefs)[27,28]. Key dimensions of empathy have been widely enumerated: emotive, cognitive, behavioral, and moral[29]. Such comprehension requires differentiating between one’s own and others’ mental states. This ability develops in repeating social interactions that result in the development of the Self, adequate affective regulation, and attachment patterns, and that mediate prosocial behavior[30,31]. Education of medical professionalism is compromised by a decline in empathy[32-34]. Protective factors and predictors of higher empathy include: resilience against stress, social support[35,36], agreeability, and conscientiousness[37].

Competency-based training in health care puts focus on applied knowledge and thus on improving practice[38,39]. More than 50% of patients support a participative approach with shared-decision making based on transparency[40,41]. In such a patient centered approach (PCA), the patient’s values, perspective, and circumstances are respected[19,42-44]. Collaboration and coordination of available services at a systems level with resource allocation continuity and improved quality of services are other features of PCA[40]. The effects of PCA have been widely researched: increased adherence to therapy among patients has been demonstrated[45], as well as reduced recovery times[25], decreased mortality[46], improved quality of life[47], and improved general health[48]. To enable the patient to be part of the decision-making process, physicians must provide understandable information[49-51]. Compassion-based interventions and a relationship built on a solid affect-cognitive level are key features[44,49].

Developing core abilities in medical professionals is relevant to improving individualized medical care. The key questions are, (1) What are the core competencies in medical history taking; and (2) What are the prerequisites to ensuring a “good” anamnesis? From a theoretical point of view, we hypothesized that empathy might be one of the identifiable themes independent of specialty and that gender effects might exist.

A qualitative descriptive study was carried out at the Medical University of Vienna (MedUni Vienna) between June 2015 and April 2016. Assumptions and views of instructors regarding desirable core competencies in medical history taking were extracted from interviews with clinicians.

All attending physicians had been practicing physicians for more than 10 years and had been instructors, mentors, and/or tutors at the MedUni Vienna.

The exclusion criteria were (1) Missing written informed consent, and (2) Professional experience of fewer than 10 years. Health care professionals not engaged with medical student supervision and training were also excluded from the survey.

More than 5000 health care professionals were invited to participate in the study via an internal communication listserv for teaching clinicians and university teachers via MedUni Vienna-list.

The instructors were chosen by Löffler-Stastka H according to the representation of medical specialties in Vienna/Austria in order to reflect this real-life distribution. Unfortunately, the original aim of equal numbers of male and female physicians interviewed could not be met due to the actual gender distribution of physicians in Vienna/Austria.

Thus, 33 attending physicians who both agreed to participate in the study and matched the required specialty-distribution were included.

The interview was standardized and semi-structured, with 16 open-ended questions developed by an interdisciplinary team. The questions allowed free association in order to carry out qualitative content analysis[52]. Questions about the interviewee’s own experience in communication and medical history taking and their experience with and memory of their observed medical student’s performance during training at their department were investigated. The interviews were all carried out personally at the MedUni Vienna; the setting did not change considerably (interview duration: 45 min). The attending physicians’ interviews were all carried out by four different female interviewers (three medical students and one educational scientist). These interviewers were instructed and supervised by Löffler-Stastka H.

The interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and imported into the program Atlas.ti[53]. Standard background questions (age/specialization of the attendant physician) were asked at the beginning of the interview.

Results were analyzed by conducting a qualitative computer-based content analysis of the interviews[54] using the program Atlas.ti.

For more information about these methods and content analysis, please refer to the diploma thesis of Zervos, K[52].

The study design complies with the ethical standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK-Nr. 1381/2015).

As the questions did not include questions about any individual student’s performance, but rather relied on the memory and experience of the interviewee, supervised students remained anonymous to the interviewers and the authors of the current study.

As mentioned above, the distribution of specialties in this study is similar to the Viennese/Austrian population of clinicians[52]. Thirteen of the 33 interviewed attending physicians were female, and the remaining 20 were male. In Table 1 we present the distribution of attending physicians in terms of their specialties and sex.

| Group | Specialty | Sex | Total (n =32) | |

| Female (n = 13) | Male (n = 19) | |||

| Internal medicine | General internal medicine; Gastroenterology; Cardiology | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Surgical specialties | General surgery; Neurosurgery; Visceral surgery; Thoracic surgery; Vascular surgery | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Surgical subspecialties | Gynecology; ENT | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Non-surgical subspecialties | Anesthesiology; Neurology; Psychiatry | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Pediatrics | Pediatrics; Child and adolescent psychiatry | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| General medicine | General medicine | 5 | 2 | 7 |

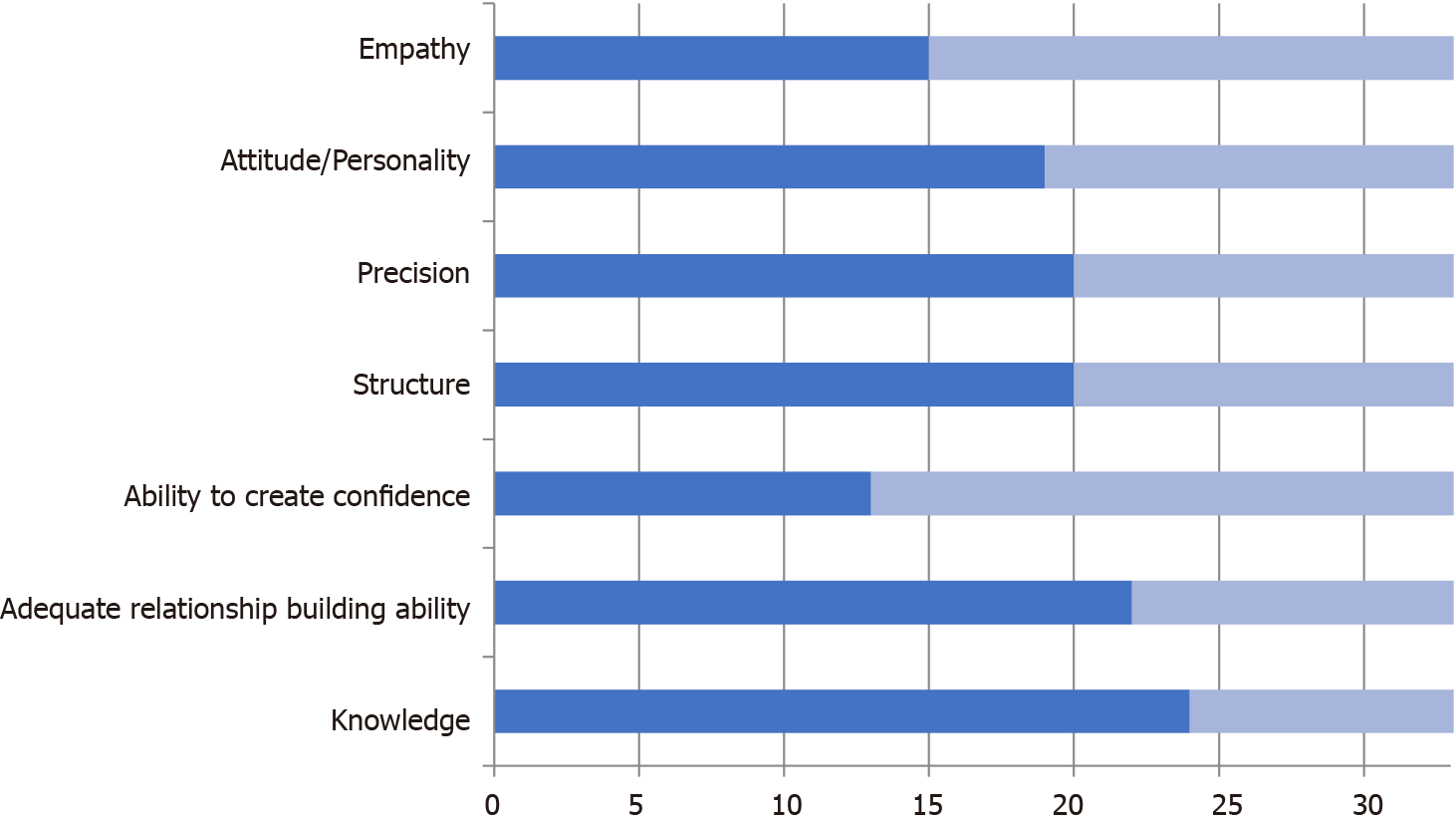

Associations of the participating attending physicians in this study can be arranged into positive (knowledge, ability to establish a relationship/trust, structure, accuracy and attitude/empathy; Figure 1) and negative ones (language barrier, lacking trust/relationship, or time, interruptions, incomplete) (Table 2).

| Percent | n = 33 | ||

| Positive associations | |||

| Knowledge | 72.73 | 24 | |

| Relationship building: + | 66.67 | 22 | |

| Trust: + | 39.40 | 13 | |

| Structure | 60.61 | 20 | |

| Precision | 60.61 | 20 | |

| Attitude | Personality | 57.58 | 19 |

| Empathy | 45.45 | 15 | |

| Negative associations | |||

| Language barrier | 33.33 | 11 | |

| Relationship building: - | 48.48 | 16 | |

| Trust: - | 15.15 | 5 | |

| Incomplete information gathering | 27.27 | 9 | |

| Time pressure | 30.30 | 10 | |

| Interruptions | 18.18 | 6 | |

“Knowledge” was the requirement most often identified in experts speaking about medical history taking; 24 participants mentioned knowledge. Physicians were allowed to mention themes several times. When counting the quotes per specialty/specialty group and correcting for the number of participants per group, general practitioners, pediatricians and non-surgical subspecialties (e.g., psychiatrists, anesthetists, etc.) scored highest, while surgical specialties, surgical subspecialties and internists scored lower (Table 3). No gender-specific difference was found. The theme “structure” was mentioned by 20 participants, often in conjunction with “knowledge”.

| % quotes | n quotes | n specialists | n (q)/n (s) | |

| Internal medicine | 13.96 | 6 | 7 | 0.86 |

| General medicine | 27.90 | 12 | 7 | 1.71 |

| Non-surgical subspecialties | 20.93 | 9 | 6 | 1.50 |

| Paediatrics | 11.63 | 5 | 3 | 1.67 |

| Surgical specialities | 18.60 | 8 | 6 | 1.34 |

| Surgical sub-specialities | 6.98 | 3 | 3 | 1.00 |

| Total | 100 | 43 | 32 |

“Establishing a relationship” was another recurrent theme; it was found in 22 of the interviews, with a total of 53 quotes about it. The “ability to create trust” was mentioned in strong association with the attachment-related category. Most quotes on relationship-building were collected from interviews with non-surgical subspecialties, general surgeons, and pediatricians (Table 4). Interestingly, internists and surgeons from surgical subspecialties (ENT, gynecology) mentioned this ability the least often.

| % quotes | n quotes | n specialists | n (q)/n (s) | |

| Internal medicine | 7.55 | 4 | 7 | 0.57 |

| General medicine | 18.87 | 10 | 7 | 1.43 |

| Non-surgical subspecialties | 32.08 | 17 | 6 | 2.83 |

| Paediatrics | 11.32 | 6 | 3 | 2.00 |

| Surgical specialities | 26.42 | 14 | 6 | 2.33 |

| Surgical sub-specialities | 3.77 | 2 | 3 | 0.67 |

| Total | 100 | 53 | 32 |

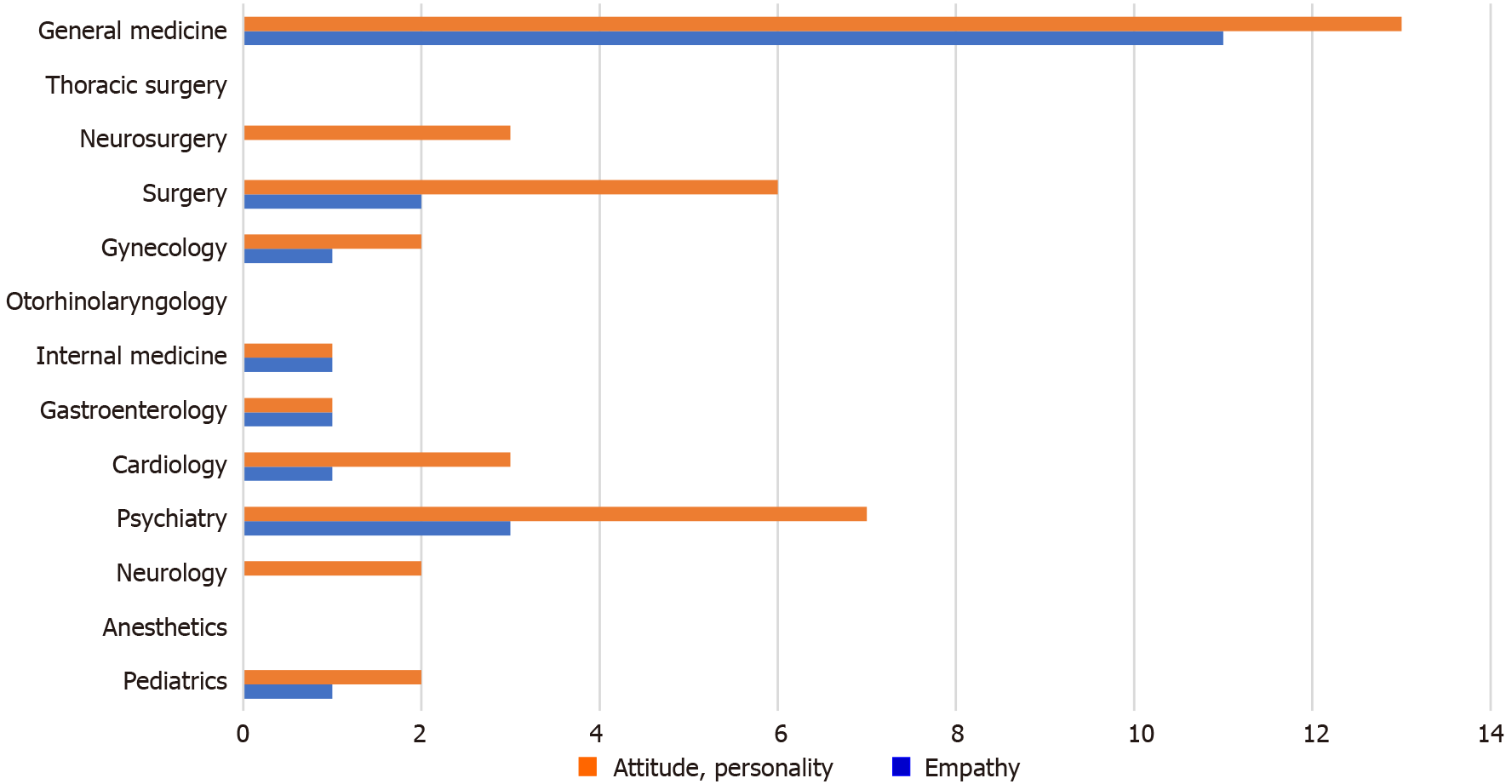

When asked about what they considered an ideal anamnesis, 19 attending physicians mentioned the health professionals’ “attitude and personality” as important, with a presumably positive impact on the quality of the patients’ history-taking process.

Furthermore, in 15 interviews, “empathy” was isolated as being important (21 quotes). Representatives of general medicine and psychiatry often mentioned quotes relating to “attitude” and “empathy” in ideal history taking (Figure 2). In regards to the mention of “attitude”, we saw a minor gender-specific difference: 61.53% of questioned female attending physicians made quotes relating to “attitude” as an important tool in history taking as opposed to 55% of their male colleagues.

With respect to mentioning “empathy”, we were able to identify a robust gender-specific frequency in favor of female attending physicians: 61.54% of questioned female attending physicians mentioned “empathy” in the context of a favorable influence on history taking, whereas only 35% of male colleagues made similar quotes.

The opposite was true for “precision”, identified in 20 interviews (25 quotes). “Precision” was mostly mentioned by male physicians (70%). However, “precision” was, above all, found to be especially important to surgeons, with a higher percentage of males in this subgroup (66.67%).

When remembering their students’ overall performance and reflecting upon desirable characteristics in anamnesis taking, the importance of knowledge (69.70%, n = 23) and showing interest for the patient (63.64% n = 21), together with attitude (66.67%, n = 22), empathy (33.33%, n = 11), and structure (51.52%, n = 17) were mentioned more often than experience (36.36%, n = 12).

When asked to remember one concrete example of a student taking a medical history, health care professionals described empathic behavior and a positive attitude as much as they did the lack of it. Concerning the students’ performance, attitude and showing empathy/empathic behavior were included in one coding.

Positive aspects: Observed students’ interest, motivation, and engagement were remembered by 16 attending physicians (48.48%).

Eleven of the attending physicians mentioned their students’ attitude in the context of having a positive impact on the quality of their respective history taking (34.38%). Three of the physicians mentioning attitude were female and eight were male (i.e. 23.08% of all questioned female physicians, and 35% of all interviewed male physicians). We identify this as a gender-specific difference. These observations were equally distributed among all represented specialties.

Negative aspects: When asked to remember observations perceived as unfavorable, poor precision or incompleteness (54.55%; n = 18), insufficient structure (due to inadequate knowledge 24.14% or failed clinical reasoning 15.15%) were often mentioned.

Attitude was observed to influence the medical history taking negatively by 11 (33.33%) of the attending physicians. No gender-specific effect was found.

Dimensions identified as being relevant to anamnesis-taking included “knowledge” (mentioned by 24 participants), soft skills (“empathy”, “relationship building ability”, “trust”, “attitude”), methodical approach (“structuring”, “timing”, “precision”, “completeness of information-gathering”), as well as environmental ones (“time pressure”, “interruptions”, “language barrier”).

As the interview asked about memories of ideal anamnesis-taking, and two categories were already given through the structure of the questions (i.e. positive vs negative associations), we suggest that future research should explore the identified dimensions along a continuum ranging from “ideal” to “abysmal”.

One of the observations made in the present investigation was that negative associations were at first in timing, or more readily made by most participants when freely associating about taking an anamnesis. Thus, experience might lead to insight into the pitfalls of human conversations. Another explanation for this could be implicit bias found in the effects of supervision and quality control.

In assessing memories and observations, due to the known link between affective loading, accessibility, and storage of memory contents, the categories derived from this analysis are likely to be more accessible to clinicians in their actual clinical environment. An interview indirectly assesses the expert’s ability to mentalize one’s own and others’ mental states. Overall, experts showed a reflected and integrated view, mentioning both positive and negative memories.

In the present qualitative analysis of interviews on memories regarding anamnesis, relationship-building was mentioned to be an important skill, as was empathy.

Although the frequency of quotes that emphasize the importance of knowledge, attitude, and empathy differed among the included specialty groups (i.e. n quotes about a specific theme/n participants of the group), this finding must be interpreted with caution. What does it really mean if a theme is mentioned more than once by a given participant in a semi-structured interview? One ability often mentioned in conjunction with “knowledge” by the participants in this actual study was the ability to structure a discourse. To discuss a matter in a structured way within a limited timeframe, it may be sufficient to mention the importance of a specific theme once and then proceed to the next. However, mentioning the importance of something multiple times could also be a way of addressing the importance of the subject. Thus, it might be the case that observed differences between specialties do exist (Table 3 and Table 4). The importance of knowledge was mentioned most often by general practitioners, pediatricians, and non-surgical specialties. The ability to establish a relationship was mentioned most often by non-surgical subspecialties, general surgeons, and pediatricians.

Integrating knowledge from different disciplines will become more challenging as scientific findings expand.

Interestingly, when asked to remember a concrete example of a student performing a good anamnesis, interest, motivation, and engagement were the main themes. Differing themes arose only when freely associating about theoretical history taking. Methodical issues prevailed when remembering a negative example (i.e. lacking precision, completeness, structure). Environmental aspects and explicitly pronounced relationship-building factors (besides engagement) were not mentioned in this context, either meaning that actual medical history taking does not usually lack these aspects, or that suppression impeded the memories of said aspects in contrast to when the task consisted predominantly of recall and theoretical conceptualization.

Interventions aiming to enhance students’ communication skills often lack both effectiveness and comparative effectiveness analyses[55]; further research on this topic is needed.

Enhancing learning, especially the accessibility of learned memory contents when related to skills and applied knowledge (i.e. not to recall theoretical knowledge), has been extensively investigated. Accessibility of attitudes from memory seems to be a function of the manner of attitude formation. With regards to attitude, one can distinguish the process of attitude formation, attitude accessibility, and attitude-behavior consistency, such that one may begin to investigate how and which specific attitudes affect later behavior[56]. A meta-analysis assessing factors relevant to attitude-behavior relation found that direct behavioral experiences produce stronger object-evaluation associations and more accessible attitudes. Behavior is determined by attitudes that are accessible and stable over time, and that affirm effects of direct experience, attitude, and confidence based on one-sided information[57].

The role of affectivity in attitude formation and its role in knowledge and skill development is obvious. Emotion seems to guide attention in learning and determines the availability of memory contents[58]. The so-called “seeking system” initiates memory and learning, as well as generating positive emotions, hope, expectancy, and enthusiasm[59].

The relevance of embodied empathy for learning has also been suggested[60]. Observation and imitation in empathic social relationships lead to the acquisition of embodied skills. A synchronization of intentions and movements seems to occur in empathic relationships with skilled practitioners, shaping the student’s perception[58]. Describing embodied knowledge is difficult, as it is not mediated through words alone, but rather learned through lived and shared experiences that established meaning.

Empathy has been classified as a basic relationship skill involving resonance and communication, and is especially relevant when aiming at patient-centered care[20,48,61]. An intrinsic disposition for empathy has been claimed and has been shown to be trainable[14-16,62-64].

Empathy levels in practitioners and therapists are quite variable. Health care professionals with high levels of empathy seem to be more vulnerable to stress-related mental conditions (e.g., burn out/exhaustion and compassion fatigue)[65-67] with a protective role of compassion satisfaction, and sensory processing sensitivity as a risk factor[68].

Studies assessing empathy in students often rely on self-assessment. Self-perceived empathy declines during medical school[18,24,36,69-72] and seems to depend on specialty choice[33,34,72], with higher perceived empathy in patient-oriented specialties. The decrease in empathy can be attributed to increased negative emotions such as stress and anxiety, which are highly dependent on context (e.g., workload, exposure to suffering and death, work hours, sleep deprivation) and impede empathy[18,35,70,73,74]. With the increase of negative affects during medical formation, remembering negative contents is more likely to influence accessible attitude.

How physicians spend their time during their workday has been analyzed for different specialties with very different profiles of work tasks and emphasis on communication skills, work-related stress, and job satisfaction[75-77].

Analysis of empathy profiles of psychotherapists shows a four-way dependence on competence in perspective taking, their tendency to experience personal distress, their fantasy (i.e. their ability to identify with fictional characters), and their empathic concern (i.e. the ability to feel compassion towards a person in distress)[78]. The profiles distinguish between types that may be characterized as “average”, “insecure-self-absorbed”, therapists showing “empathic immersion”, and those who are “rational empathic”. With experience, the “rational empathy” becomes more prevalent.

A given clinician’s empathic range and flexibility seem to be modifiable independent of context; however, circumstances can influence them. Emergency settings, for example, have been shown to produce a high level of burnout frequency[79,80], which reduces predisposition for empathic behavior.

Especially interesting is the observation of students’ positive attitude and empathic behavior and their positive impact on the quality of history taking as perceived across all specialties, instead of merely mentioning attitude and empathy as important tools on a theoretical level. Physicians mentioning attitude and empathy in the theoretical context of ideal history taking represent predominantly general medicine and psychiatry, and are mainly female. The observation of the positive impact of attitude and empathy on actual student history taking is described mainly by male health care professionals, without showing any predominance of specialty. Again, accessibility of memory contents depends on the content’s affective links and its links to real experience[59,81,82]. Cognitive processes are influenced by emotions[83]: “Substantial evidence has established that emotional events are remembered more clearly, accurately, and for longer periods than are neutral events”[59]. Thus, contents normally less accessible are easier to remember when an actual experience is associated. The fact that more women mention attitude and empathy even when theorizing, whereas men only do so when remembering an actual observation, could indicate a difference in perceived value and importance of the theme, perhaps due to different socialization, among other things.

Observations of healthcare professionals are supported by extensive data describing the practitioners’ positive impact on patient health, shortening the diagnostic process[23-26].

When dealing with embodied knowledge, there may be a gap between recalled themes and the actual performance of practitioners, particularly as evidence shows that empathic therapists show this (socially desirable) behavior rather automatically, independent from their conscious intention or personality. However, it is to be noted that even if attitude (including empathy) is described by fully one-third of the questioned attending physicians as having been observed among students (with positive impact on their history taking), a similar proportion of them recognize deficits in this area. Interventions promoting empathy and improving attitudes, including underlying processes of self-reflection and mentalization, could enhance the acquisition of this skill[84-88].

Attitude is particularly influenced by those more senior than us[89]. Therefore, change cannot only be implemented at the undergraduate-level but must also impact the postgraduate system.

Whether perspective representation or simply a sensitivity to the perspective of others is necessary for successful communication has been questioned; however, the importance of perspective-taking for systematic success is well known[90]. Forming representations of the mental and affective states of others determines attachment and mind-reading abilities[82]. Memory and attention processes have an important role in enabling communication[91,92]. Becoming sensitive to one another’s perspective can happen due to contextual effects, like when information is made available from priming and automatic recall, together with attention cueing[90]. When trying to mentalize, retrieval of memory traces that include or overlap with all kinds of information that is shared occurs[91]. Cues about what a person might already know about what she/he can see or hear (e.g., conversational common ground, knowledge, local routines, etc.) might be accessible. How a person perceives reality, however, might be a less straightforward guess to make. A modulating role for such memories in mentalizing abilities has been suggested. When mentalizing, whole events (real or imagined), as well as episodic memories linked to the target person, are remembered and become (mentally) ingrained. Thus, the content and quality of imagination might play a central role in more or less adequate attributions of mental states[82].

However, using one’s own theories of mind to infer others’ intentions requires motivation and effort[90,93]. Experiments by Lin et al[93] showed that attention-demanding secondary tasks reduce people’s ability to mentalize. Lower working memory capacity predicted less effective use of the theory of mind.

Thus, the everyday routine in clinical settings, what with the necessity of shiftwork, multi-tasking, as well as frequent interruptions, might negatively influence performance[94], learning, and accessibility of memory (including attitudes). Moreover, other skills not considered essential by financing bodies of healthcare providers may also fall by the wayside. Contemporary health finance policies might increase pressure to focus on higher-paying tasks, potentially incentivizing unfavorable behaviors. However, evidence for empathy and attitude in learning and for outcomes in healthcare already exists.

Future research into social cognition in health care should focus on the conditions that increase the likelihood that other perspectives are represented during conversations, counterbalance an egocentric perspective, and enhance behavior.

Experience-based training programs could address the gap between theoretical conceptions of the importance of empathy for self- and patient care, as well as improve mentalizing and emotional regulation, which is necessary for letting empathy guide social behavior. These interventions implement specific feedback mechanisms that are easy to establish in clinical contexts, such as peer-supervision, once the basic concept is taught[18]. Remembering, collecting, and using the information to predict what others think, feel, or might do depends on an individual’s cognitive abilities, context, and disposition. Research into the mechanism of change revealed that change most likely happens when intense and enduring negative affect accumulates; thus, motivation to modify views first arises, followed by a systemic reorganization.

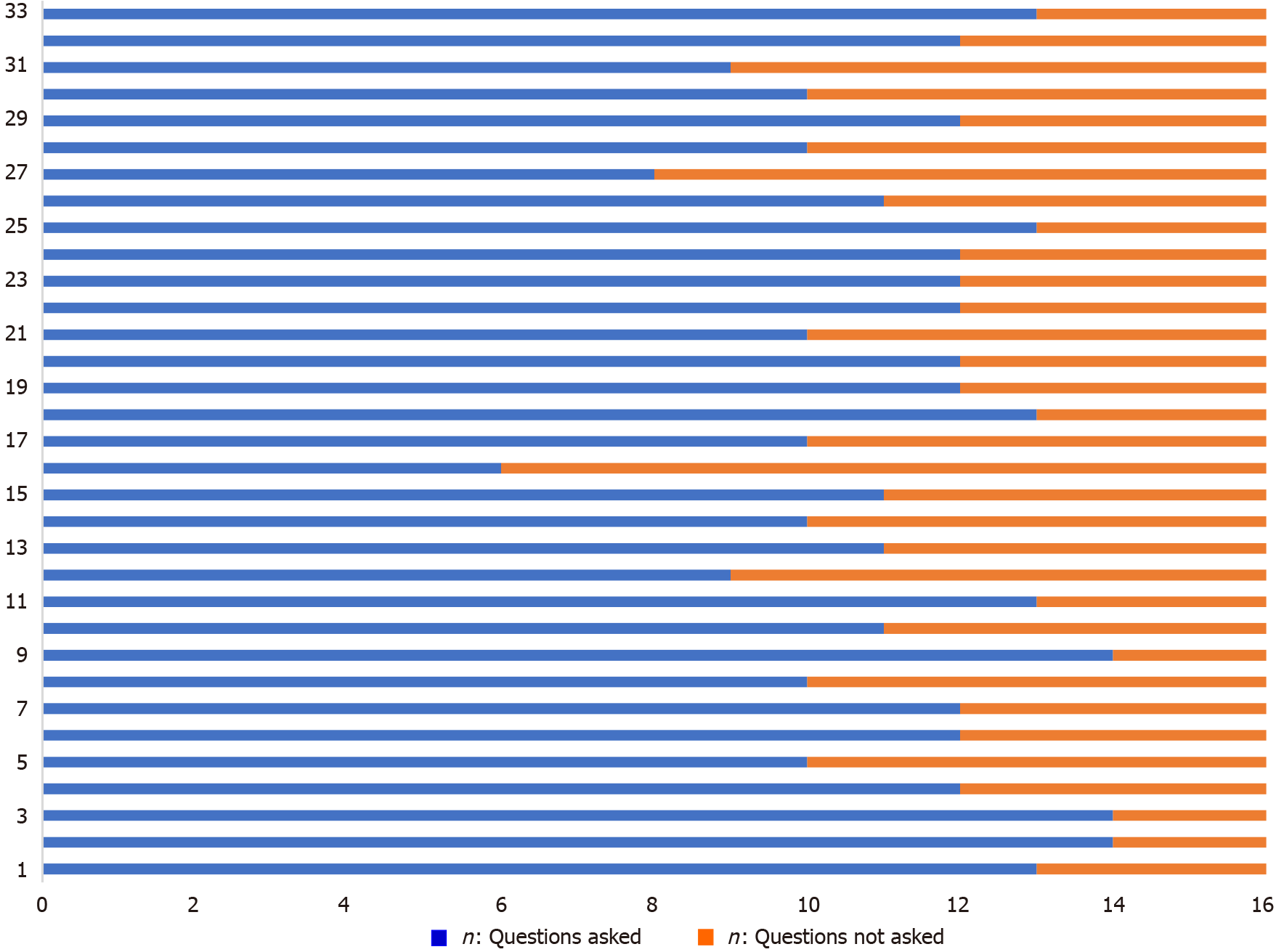

As the interviews were conducted in a semi-structured way, and open-ended questions were predominant, the number of questions varied between the interviews due to time constraints. Also, after 17 interviews, one additional question was added to the initial catalog of 15 questions. No question was asked in every interview. For the percentage of questions asked, see Figure 3. The number of questions asked ranged from 6 to 14 (mean = 11.30, SD = 1.79), with an average of 4.70 questions not asked. However, questions overlapped in terms of their subject, as the questionnaire aimed to investigate the topic in depth from different viewpoints.

Inductive category development as a way of qualitative content analysis has been questioned, because derived definitions do not appear to be functionally justified, and practical relevance has been doubted[95,96]. Alternative frameworks for category formation have been recommended, suggesting that coding decisions should be made in accordance with the individual study at hand. However, regarding the current investigation (explorative design), inductive category formation was adequate in minimizing the possible influence of preexisting assumptions.

One should also account for possible bias arising from all interviewers being female.

Finally, our sample size was somewhat small (n = 33), as the approach was a hypothesis-generating one. Nevertheless, our sample might be quite representative, as the number of participants per sub-specialty was selected according to the distribution of medical sub-specialties in Austria. However, depending on circumstances (e.g., clinical department differences) and socialization, conceptions of the importance of empathy and communication might vary.

Our findings show that dimensions identified as being relevant to anamnesis-taking included expert knowledge-related skills, as well as soft skills, methodical, and environmental ones.

The analysis of interviews adds to the ongoing theoretical discussion of competency-based education in medicine.

If a change should be facilitated - either in individual patients for a better health status, or society at large for overcoming difficult circumstances - understanding of minds, reflection and empathy is needed. These change processes with the mentioned ingredients should be assessed further for the long run.

Knowing one’s own mind to transform oneself is essential. Empathy is needed in the context of patient-centered care.

To assess how medical students perform in their ability to provide an empathic medical history taking.

Interviews with experienced physicians/mentors.

Differences between medical specialties are shown, but in general all physicians claim for a strengthening of empathy.

Concise structure and an empathic attitude are necessary for the understanding of minds in order to get the needed information for adequate clinical reasoning and clinical decision making.

Understanding of minds and mentality can be facilitated, trained and strengthened.

We thank the participants for their engagement, and the reviewers for their comments that helped to improve the manuscript. The authors want to appreciate the contribution of the Medical University of Vienna and of the NÖ Landesgesundheitsagentur, legal entity of University Hospitals in Lower Austria, for providing the organizational framework to conduct this research.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Health Care Sciences and Services

Country/Territory of origin: Austria

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li Y, Zyoud SH S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang JL

| 1. | Leader D. Psychoanalysis: Freud’s theory and the ideas that have followed. The Guardian 2009. [accessed 2021 Mar 24]. Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/mar/07/freud-jung-psychoanalysis-behaviour-unconscious. |

| 2. | Thompson WK, Savla GN, Vahia IV, Depp CA, O'Hara R, Jeste DV, Palmer BW. Characterizing trajectories of cognitive functioning in older adults with schizophrenia: does method matter? Schizophr Res. 2013;143:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fattahi H, Abolghasem Gorji H, Bayat M. Core competencies for health headquarters: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peterson MC, Holbrook JH, Von Hales D, Smith NL, Staker LV. Contributions of the history, physical examination, and laboratory investigation in making medical diagnoses. West J Med. 1992;156:163-165. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Oxford Medical Education. History Taking - Overview. Oxford Medical Education 2016. [accessed 2021 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.oxfordmedicaleducation.com/history/medical-general/. |

| 6. | Byszewski A, Gill JS, Lochnan H. Socialization to professionalism in medical schools: a Canadian experience. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Passi V, Doug M, Peile E, Thistlethwaite J, Johnson N. Developing medical professionalism in future doctors: a systematic review. Int J Med Educ. 2010;1:19-29. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huddle TS; Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Viewpoint: teaching professionalism: is medical morality a competency? Acad Med. 2005;80:885-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pohontsch NJ, Stark A, Ehrhardt M, Kötter T, Scherer M. Influences on students' empathy in medical education: an exploratory interview study with medical students in their third and last year. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nedelmann C, Ferstl H. Die Methode der Balint-Gruppe. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1989. Available from: https://beluga.sub.uni-hamburg.de/vufind/Record/025633619. |

| 11. | Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76:390-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 604] [Cited by in RCA: 566] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Novack DH, Dubé C, Goldstein MG. Teaching medical interviewing. A basic course on interviewing and the physician-patient relationship. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1814-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Medical University of Vienna. Studienplan and Studienplanführer - Studium an der MedUni Wien. Medizinischen Universität Wien. [accessed 2021 Mar 10]. Available from: https://www.meduniwien.ac.at/web/studierende/mein-studium/diplomstudium-humanmedizin/studienplan-studienplanfuehrer/. |

| 14. | Drdla S, Löffler-Stastka H. Influence of conversation technique seminars on the doctoral therapeutic attitude in doctor-patient communication. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128:555-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ludwig B, Turk B, Seitz T, Klaus I, Löffler-Stastka H. The search for attitude-a hidden curriculum assessment from a central European perspective. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018;130:134-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee KC, Yu CC, Hsieh PL, Li CC, Chao YC. Situated teaching improves empathy learning of the students in a BSN program: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;64:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Elliott R, Bohart AC, Watson JC, Murphy D. Therapist empathy and client outcome: An updated meta-analysis. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2018;55:399-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Seitz T, Längle AS, Seidman C, Löffler-Stastka H. Does medical students' personality have an impact on their intention to show empathic behavior? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21:611-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Roumie CL, Greevy R, Wallston KA, Elasy TA, Kaltenbach L, Kotter K, Dittus RS, Speroff T. Patient centered primary care is associated with patient hypertension medication adherence. J Behav Med. 2011;34:244-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Howick J, Mittoo S, Abel L, Halpern J, Mercer SW. A price tag on clinical empathy? J R Soc Med. 2020;113:389-393. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Howick J, Moscrop A, Mebius A, Fanshawe TR, Lewith G, Bishop FL, Mistiaen P, Roberts NW, Dieninytė E, Hu XY, Aveyard P, Onakpoya IJ. Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J R Soc Med. 2018;111:240-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Brown R, Dunn S, Byrnes K, Morris R, Heinrich P, Shaw J. Doctors' stress responses and poor communication performance in simulated bad-news consultations. Acad Med. 2009;84:1595-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, Miller CS, Gauld-Jaeger J, Bost P. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287:2951-2957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, Vergare M, Magee M. Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1563-1569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 723] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rakel DP, Hoeft TJ, Barrett BP, Chewning BA, Craig BM, Niu M. Practitioner empathy and the duration of the common cold. Fam Med. 2009;41:494-501. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, Nordstrom B, Cretin D, Svarstad B. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 1998;36:1138-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 672] [Cited by in RCA: 647] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Blair J, Sellars C, Strickland I, Clark F, Williams A, Smith M, Jones L. Theory of mind in the psychopath. J Forensic Psychiatry. 1996;7:15-25. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cerniglia L, Bartolomeo L, Capobianco M, Lo Russo SLM, Festucci F, Tambelli R, Adriani W, Cimino S. Intersections and divergences between empathizing and mentalizing: Development, recent advancements by neuroimaging and the future of animal modeling. Front Behav Neurosci. 2019;13:212. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Morse JM, Anderson G, Bottorff JL, Yonge O, O'Brien B, Solberg SM, McIlveen KH. Exploring empathy: a conceptual fit for nursing practice? Image J Nurs Sch. 1992;24:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Fonagy P, Target M. Predictors of outcome in child psychoanalysis: a retrospective study of 763 cases at the Anna Freud Centre. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1996;44:27-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Schoeps K, Mónaco E, Cotolí A, Montoya-Castilla I. The impact of peer attachment on prosocial behavior, emotional difficulties and conduct problems in adolescence: The mediating role of empathy. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Seitz T, Gruber B, Preusche I, Löffler-Stastka H. [What causes the decrease in empathy among medical students during their university training? Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2017;63:20-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chen D, Lew R, Hershman W, Orlander J. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1434-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Newton BW, Barber L, Clardy J, Cleveland E, O'Sullivan P. Is there hardening of the heart during medical school? Acad Med. 2008;83:244-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Park KH, Kim DH, Kim SK, Yi YH, Jeong JH, Chae J, Hwang J, Roh H. The relationships between empathy, stress and social support among medical students. Int J Med Educ. 2015;6:103-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, Haramati A, Scheffer C. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86:996-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1078] [Cited by in RCA: 867] [Article Influence: 61.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Melchers MC, Li M, Haas BW, Reuter M, Bischoff L, Montag C. Similar Personality Patterns Are Associated with Empathy in Four Different Countries. Front Psychol. 2016;7:290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gruppen LD, Mangrulkar RS, Kolars JC. The promise of competency-based education in the health professions for improving global health. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 2007;82:542-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 691] [Cited by in RCA: 720] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | John JR, Jani H, Peters K, Agho K, Tannous WK. The Effectiveness of Patient-Centred Medical Home-Based Models of Care versus Standard Primary Care in Chronic Disease Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised and Non-Randomised Controlled Trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Braun B, Marstedt G. Partizipative Entscheidungsfindung beim Arzt: Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh, 2012. [accessed 2021 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/partizipative-entscheidungsfindung-beim-arzt?. |

| 42. | Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, Delbanco TL. Through the patient’s eyes: Understanding and promoting patient-centered care. Hoboken, JN: John Wiley and Sons, 2002. Available from: https://www.wiley.com/en-ie/Through+the+Patient's+Eyes:+Understanding+and+Promoting+Patient+Centered+Care-p-9780787962203. |

| 43. | Butow PN, Dowsett S, Hagerty R, Tattersall MH. Communicating prognosis to patients with metastatic disease: what do they really want to know? Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:161-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, Ferrier K, Payne S. Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ. 2001;322:468-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1830] [Cited by in RCA: 1607] [Article Influence: 100.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Meterko M, Wright S, Lin H, Lowy E, Cleary PD. Mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the influences of patient-centered care and evidence-based medicine. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1188-1204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Andersen MR, Sweet E, Lowe KA, Standish LJ, Drescher CW, Goff BA. Involvement in decision-making about treatment and ovarian cancer survivor quality of life. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124:465-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796-804. |

| 49. | Geisler LS. Das Arzt-Patient-Gespräch als Instrument der Qualitätssicherung. In: 2. Kongresses “Qualitätssicherung in ärztlicher Hand zum Wohle der Patienten“ am 26.6.2004 in Düsseldorf. Düsseldorf: Institut für Qualität im Gesundheitswesen Nordrhein Westfalen (IQN); 2004. [accessed 22 Apr21]. Available from: http://www.linus-geisler.de/vortraege/0406arzt-patient-gespraech_qualitaetssicherung.html. |

| 50. | Rogers A, Kennedy A, Nelson E, Robinson A. Uncovering the limits of patient-centeredness: implementing a self-management trial for chronic illness. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:224-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Dierks ML, Bitzer EM, Lerch M, Martin S, Röseler S, Schienkiewitz A, Siebeneick S, Schwartz FW. Patientensouveränität: der autonome Patient im Mittelpunkt 2001. [accessed 2021 Mar 9]. Available from: https://elib.uni-stuttgart.de/handle/11682/8693. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 52. | Zervos K. An ideal patient-history-taking-medical students' performance. Vienna: Medical University Vienna; 2019. [accessed 2021 Mar 11]. Available from http://repositorium.meduniwien.ac.at/obvumwhs/3311711. |

| 53. | ATLAS. ti. ATLAS.ti: The qualitative data analysis and research software. [accessed 2021 Mar 25]. Available from: https://atlasti.com/de/. |

| 54. | Fürst S, Jecker C, Schönhagen P. Die qualitative Inhaltsanalyse in der Kommunikationswissenschaft. In: Averbeck-Lietz S, Meyen M, editors. Handbuch nicht standardisierte Methoden in der Kommunikationswissenschaft Wiesbaden. Fachmedien: Springer, 2014. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 55. | Gilligan C, Powell M, Lynagh MC, Ward BM, Lonsdale C, Harvey P, James EL, Rich D, Dewi SP, Nepal S, Croft HA, Silverman J. Interventions for improving medical students' interpersonal communication in medical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2:CD012418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Fazio RH. Attitudes as Object-Evaluation Associations of Varying Strength. Soc Cogn. 2007;25:603-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 517] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Glasman LR, Albarracín D. Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: a meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:778-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 824] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Gieser T. Embodiment, emotion and empathy: A phenomenological approach to apprenticeship learning. Anthropol Theory. 2008;8:299-318. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Tyng CM, Amin HU, Saad MNM, Malik AS. The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 617] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Schmidsberger F, Löffler-Stastka H. Empathy is proprioceptive: the bodily fundament of empathy – a philosophical contribution to medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:69. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Barrett-Lennard GT. The phases and focus of empathy. Br J Med Psychol. 1993;66 ( Pt 1):3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Riess H, Kelley JM, Bailey RW, Dunn EJ, Phillips M. Empathy training for resident physicians: a randomized controlled trial of a neuroscience-informed curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1280-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Steinmair D, Horn R, Richter F, Wong G, Löffler-Stastka H. Mind reading improvements in mentalization-based therapy training. Bull Menninger Clin. 2021;85:59-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Dyer E, Swartzlander BJ, Gugliucci MR. Using virtual reality in medical education to teach empathy. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106:498-500. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Ferri P, Guerra E, Marcheselli L, Cunico L, Di Lorenzo R. Empathy and burnout: an analytic cross-sectional study among nurses and nursing students. Acta Biomed. 2015;86 Suppl 2:104-115. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, Eames C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Burn Res. 2017;6:18-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: psychotherapists' chronic lack of self care. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58:1433-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 675] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Pérez-Chacón M, Chacón A, Borda-Mas M, Avargues-Navarro ML. Sensory Processing Sensitivity and Compassion Satisfaction as Risk/Protective Factors from Burnout and Compassion Fatigue in Healthcare and Education Professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Bellini LM, Shea JA. Mood change and empathy decline persist during three years of internal medicine training. Acad Med. 2005;80:164-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Rosen IM, Gimotty PA, Shea JA, Bellini LM. Evolution of sleep quantity, sleep deprivation, mood disturbances, empathy, and burnout among interns. Acad Med. 2006;81:82-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Stratton TD, Saunders JA, Elam CL. Changes in medical students' emotional intelligence: an exploratory study. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, Veloski J, Gonnella JS. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84:1182-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 884] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Thomas MR, Dyrbye LN, Huntington JL, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. How do distress and well-being relate to medical student empathy? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Shanafelt TD, West C, Zhao X, Novotny P, Kolars J, Habermann T, Sloan J. Relationship between increased personal well-being and enhanced empathy among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:559-564. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Holzer E, Tschan F, Kottwitz MU, Beldi G, Businger AP, Semmer NK. The workday of hospital surgeons: what they do, what makes them satisfied, and the role of core tasks and administrative tasks; a diary study. BMC Surg. 2019;19:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Mache S, Kloss L, Heuser I, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA. Real time analysis of psychiatrists' workflow in German hospitals. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65:112-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Leafloor CW, Lochnan HA, Code C, Keely EJ, Rothwell DM, Forster AJ, Huang AR. Time-motion studies of internal medicine residents' duty hours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:621-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Laverdière O, Kealy D, Ogrodniczuk JS, Descôteaux J. Got Empathy? Psychother Psychosom. 2019;88:41-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Zhang YY, Zhang C, Han XR, Li W, Wang YL. Determinants of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burn out in nursing: A correlative meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Zhang Q, Mu MC, He Y, Cai ZL, Li ZC. Burnout in emergency medicine physicians: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e21462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Singer JA, Salovey P. Mood and memory: Evaluating the network theory of affect. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:211-251. |

| 82. | Gaesser B. Episodic mindreading: Mentalizing guided by scene construction of imagined and remembered events. Cognition. 2020;203:104325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Vuilleumier P. How brains beware: neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:585-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1264] [Cited by in RCA: 1336] [Article Influence: 66.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Himmelbauer M, Seitz T, Seidman C, Löffler-Stastka H. Standardized patients in psychiatry - the best way to learn clinical skills? BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:72. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Greco M, Brownlea A, McGovern J. Impact of patient feedback on the interpersonal skills of general practice registrars: results of a longitudinal study. Med Educ. 2001;35:748-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Kneebone R. Simulation in surgical training: educational issues and practical implications. Med Educ. 2003;37:267-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Schultz JH, Schönemann J, Lauber H, Nikendei C, Herzog W, Jünger J. Einsatz von Simulationspatienten im Kommunikations- und Interaktionstraining für Medizinerinnen und Mediziner (Medi-KIT): Bedarfsanalyse — Training — Perspektiven. Gr Interakt Organ. 2007;38:7-23 [. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Ziv A, Wolpe PR, Small SD, Glick S. Simulation-based medical education: an ethical imperative. Acad Med. 2003;78:783-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 589] [Cited by in RCA: 517] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Wright SM, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Howard DM, Brancati FL. Attributes of excellent attending-physician role models. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1986-1993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Apperly I. Mindreading and Psycholinguistic Approaches to Perspective Taking: Establishing Common Ground. Top Cogn Sci. 2018;10:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Horton WS. Conversational common ground and memory processes in language production. Discourse Processes. 2005;40:1-35. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Pickering MJ, Garrod S. Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behav Brain Sci. 2004;27:169-90; discussion 190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 921] [Cited by in RCA: 627] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Lin S, Keysar B, Epley N. Reflexively mindblind: Using theory of mind to interpret behavior requires effortful attention. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46:551-556 [. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Boivin DB, Boudreau P. Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2014;62:292-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Schank RC, Collins GC, Hunter LE. Transcending inductive category formation in learning. Behav Brain Sci. 1986;9:639-651. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |