Published online Jul 9, 2022. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v11.i4.341

Peer-review started: January 7, 2022

First decision: March 9, 2022

Revised: March 23, 2022

Accepted: June 3, 2022

Article in press: June 3, 2022

Published online: July 9, 2022

Processing time: 179 Days and 20.4 Hours

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can lead to social and economic impacts worldwide. In Brazil, where its adult prevalence is increasing, the epidemiology of the pediatric population is not well known, although there is a documented increase in pediatric IBD incidence worldwide. Brazil has continental dimensions, and Espírito Santo is a state of southeastern Brazil, the region with the highest demographic densities and is the economically most important in the country.

To assess the prevalence, incidence, phenotype and medications in a Southeastern Brazilian pediatric population.

Data were retrieved from the Public Medication-Dispensing System of the Department of Health in Espírito Santo state from documentation required to have access to highly expensive medication from August 1, 2012 to July 31, 2014. There were 1048 registered patients with IBD of all ages, and of these patients, the cases ≤ 17 years were selected. The data were obtained through the analysis of administrative requests for these medications and included medical reports, endoscopy exams, histopathology and imaging tests, which followed the Clinical Protocols and Therapeutic Guidelines of the Brazilian Government. Only confirmed cases of IBD were included in the study.

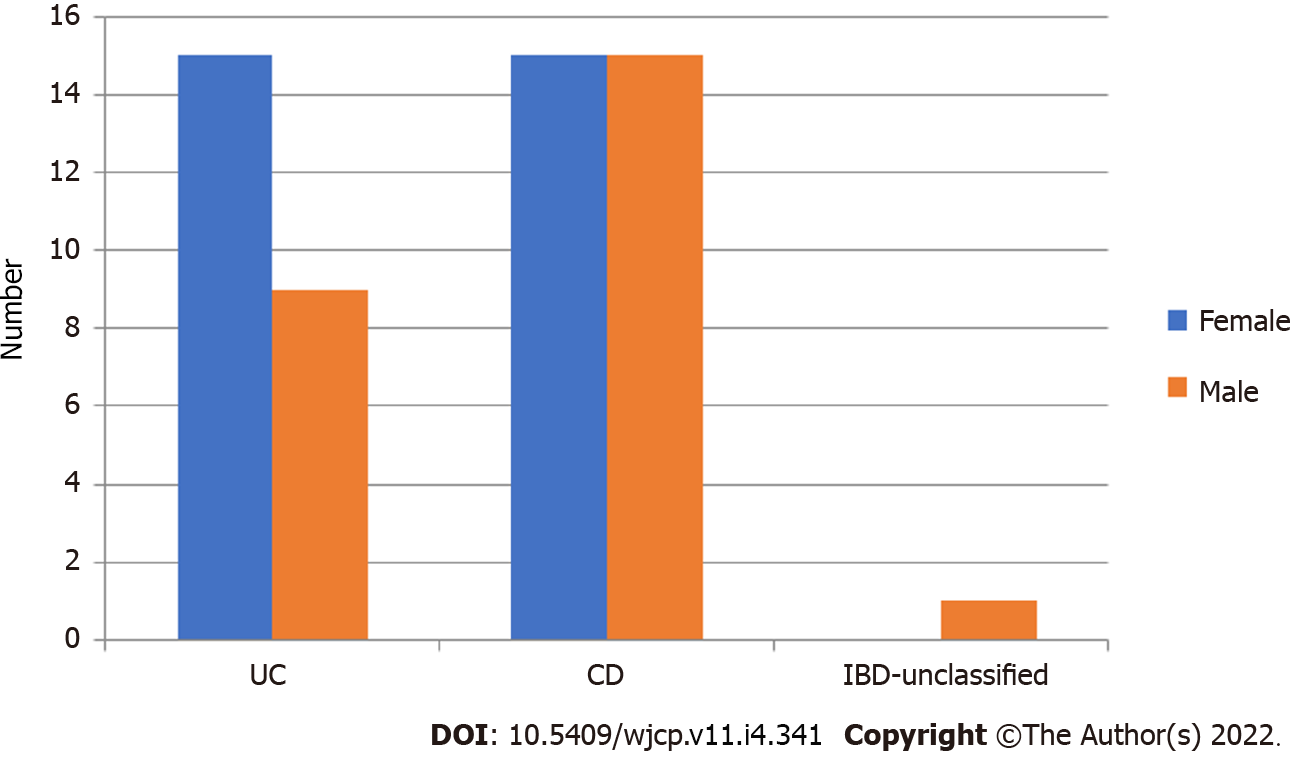

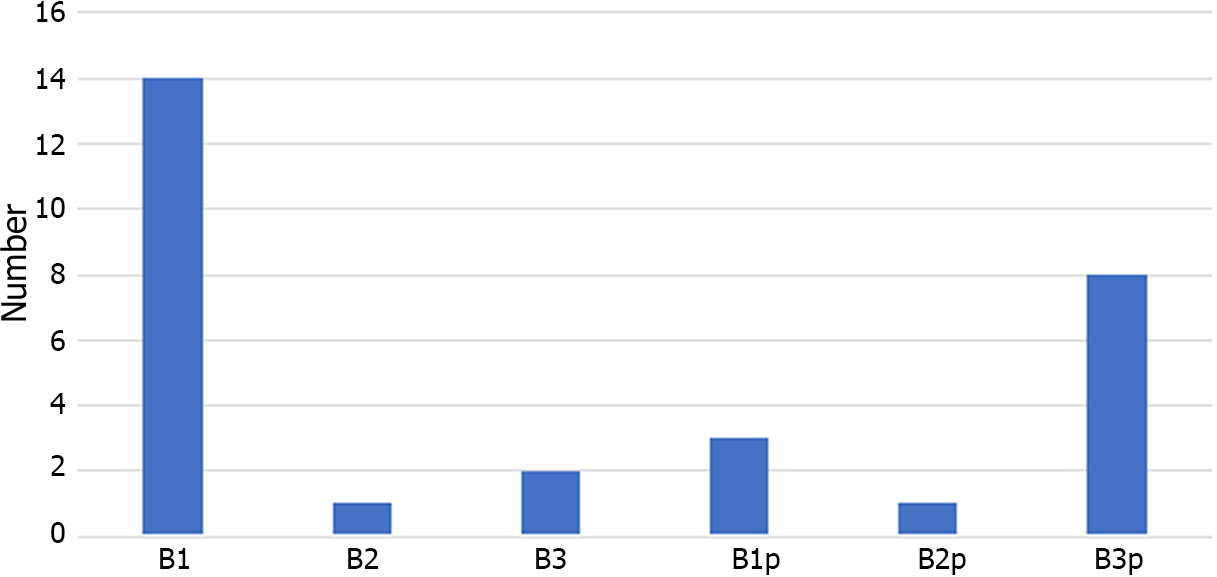

There were 55 pediatric patients/1048 registered patients (5.34%), with Crohn's disease (CD) representing 30/55 (55%), ulcerative colitis (UC) 24/55 (43.6%) and 1 unclassified IBD, a significant difference from adult patients (P = 0.004). The prevalence of IBD in pediatric patients was 5.02 cases/100.000 inhabitants; the incidence in 2014 was 1.36 cases/100.000 inhabitants. The mean age at diagnosis was 12.2 years (± 4.2). There were 7 children diagnosed up to 6 years old, 7 between 7 to 10 years old and 41 between 11 and ≤ 17 years old. There was no difference in the distribution of UC and CD between these age categories (P = 0.743). There was no difference in gender distribution in relation to adults. Children and adolescents with UC had a predominance of pancolitis, unlike adults (P = 0.001), and used aminosalicylates and immunomodulators for their treatment. Pediatric patients with CD did not present a difference in disease location but had a higher frequency of fistulizing behavior (P = 0.03) and perianal disease phenotype (P = 0.007) than adult patients. Patients with CD used more immunomodulators and biological therapy. Treatment with biological therapy was more frequently used in pediatric patients than in adults (P < 0.001).

Although the data from this study demonstrate that incidence and prevalence rates are low in southeastern Brazil, these data demonstrate the severity of IBD in pediatric patients, with the need for early diagnosis and therapy, avoiding serious damage.

Core Tip: In Brazil, where the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in adults is increasing, the epidemiology of the pediatric population is not well known, although there is a documented increase in pediatric IBD incidence worldwide. Espírito Santo is a state of southeastern Brazil, the region with the highest demographic densities and that is the economically most important in the country. Our epidemiological data, including behavior and medication, evaluate the comparison between the pediatric and adult age groups. Therefore, this study has the potential to reinforce the need for adequate care of pediatric patients with IBD, with the potential to influence public health policies.

- Citation: Martins AL, Fróes RSB, Zago-Gomes MP. Prevalence, phenotype and medication for the pediatric inflammatory bowel disease population of a state in Southeastern Brazil. World J Clin Pediatr 2022; 11(4): 341-350

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v11/i4/341.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v11.i4.341

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can lead to social and economic impacts worldwide. In Brazil, where its prevalence is increasing, the epidemiology of the pediatric population is not well known, although there is a documented increase in pediatric IBD incidence worldwide[1,2]. Represented by ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD) and unclassified inflammatory bowel disease (U-IBD), these diseases have a chronic evolution, with more severe clinical manifestations and complex treatment when started in the pediatric age group[3,4]. IBD initiation in childhood and adolescence is described in up to 25% of patients[3,5].

The main signs and symptoms of IBD in the pediatric age range are diarrhea, abdominal pain and stunting, which can be confused with other diseases, causing a delay in diagnosis and inappropriate therapies. Considering the more aggressive phenotypes and worse therapeutic response in this age group, early recognition of the disease becomes extremely important[4-6].

There are still few epidemiological studies in the pediatric age group; however, this information is relevant as it can define characteristics specific to each region and provide improvements to the health system with programming of costs related to propaedeutics and treatment. In addition, early diagnosis and adequate therapy could provide better results, that is, deep remission, with better physical, social and school health quality[4].

Some epidemiological studies of IBD have been carried out in Brazil[7,8]; however, the majority were in reference centers for adult care, and other recent studies used the database of records of the “Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS)” which is Brazilian Health System[9,10]. Brazil has continental dimensions, but there is no obligation to notify a case of IBD in the country, and there is no unified registry, although the Brazilian government provides medication for the treatment of IBD through the sector of the supply of high-cost drugs for chronic diseases, which all citizens are entitled to access. The aim of this study is to evaluate the epidemiology, phenotype and treatment of IBD in pediatric patients in the state of Espírito Santo, a state of Southeastern Brazil, the region with the highest demographic densities and most economic importance in the country, to contribute to possible improvements, both in the assistance and administrative areas of the health service.

The study was conducted between August 1, 2012, and July 31, 2014, in the Public Medication Dispen

This study evaluated patients with a confirmed diagnosis of IBD aged ≤ 17 years old from a total sample containing 1048 patients of all ages, with phenotype and treatment available, who received medications through the Federal Government and for whom the incidence and prevalence of IBD was determined in a previous study[9].

In medication-dispensing services, the evaluation is conducted by a gastroenterologist doctor, in this case, the author of the research, who was responsible for dispensing the medication for IBD. The data analyzed were obtained through the analysis of administrative requests of these medications and included personal identification documents, medical reports, endoscopy exams, histopathology and imaging tests, which followed the Clinical Protocols and Therapeutic Guidelines of the Brazilian Government[11,12].

As the study included patients aged 17 years, we chose to use the Montreal classification to establish the phenotype of IBD for CD and UC[13]. For the patients whose endoscopic examination, imaging, and histopathological and laboratory examinations associated with medical reports had difficulty in defining CD and UC, the terminology “unclassified inflammatory bowel disease” (U-IBD) was applied.

Dependent variables included the diagnosis, IBD classification, medications, new cases (diagnosis made less than 12 months before the time of the process of evaluation at the Pharmaceutical Assistance) and old cases (diagnosis older than 12 mo), distributed in assessment year 1 (August 1, 2012 to July 31, 2013) and year 2 (August 1, 2013 to July 31, 2014). Independent variables included age and sex.

The study was conducted with secondary data, and some information may not be complete. Not all patients with CD included in the study had an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy/biopsy, and magnetic resonance. Medical reports and few older documents have been damaged due to time, making it impossible to define the localization of the disease in some cases.

In Brazil, medications for IBD are expensive and provided by the Public Health care System for patients treated in the public and private systems. However, it is possible that some patients in the private system obtained their oral medications directly from drugstores without utilizing the public system.

This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Nossa Senhora da Gloria Children’s Hospital (CAAE 19602813.8.0000.5069) after obtaining authorization from the State Office for Pharmaceutical Assistance. The terms clarification and consent were waived because the data used were secondary data.

An Excel spreadsheet was used to collect all the data, and all patients aged ≤ 17 years of age when diagnosed were selected, building a new Excel table that was analyzed using SPSS Statistics 20.0 software. Data were tabulated and analyzed through descriptive analysis of frequencies, percentages, averages, and standard deviations (SD). To determine associations between categorical variables, a chi-square test was used, and Fisher’s exact test was also used when appropriate. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) were used to calculate prevalence and incidence based on the estimated census of 2014, in which the total estimated population of Espírito Santo was 3.885.049 inhabitants[14] and the population ≤ 17 years old was 1.095.669 inhabitants[15]. To calculate incidence, new cases arising in the second year of the study were used (August 1, 2013, to July 31, 2014), and prevalence was calculated as the number of children (≤ 17 years) who received dispensed IBD-related drug prescriptions during the study period that ended on July 31, 2014.

Out of a total sample of 1048 patients analyzed in medication-dispensing services at the Pharmaceutical Assistance in Espírito Santo who were diagnosed with IBD, 55 (5.24%) were diagnosed at ≤ 17 years old. There were predominance of CD 30/55 (54.5%), with UC 24/55 (43.6%) and 1 had a diagnosis of U-IBD, different from the sample of adult patients (P = 0.004).

In 2013, 33 patients were registered, and in 2014, 22 patients were registered, for a total of 55 cases. Of the 22 cases registered in 2014, 14 were new cases: 7 were CD and 7 were UC. The calculated prevalence and incidence are based on the estimated census of 2014[14,15]. The prevalence of IBD in pediatric patients in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, was 5.02 cases/100.000 inhabitants/year, while the incidence in 2014 (year) was 1.27 cases/100.000 inhabitants/year. The prevalence of CD was 2.73/100.000 inhabitants, and the incidence was 0.63 cases/100.000 inhabitants/year. The prevalence of UC was 2.19/100.000 inhabitants, and the incidence was the same as that of CD (0.63 cases/100.000 inhabitants).

Seven children were diagnosed up to 6 years old, 7 were diagnosed between 7 to 10 years of age and 41 were diagnosed between 11 and 17 years of age, and there was no difference in the distribution of UC and CD between these age categories (P = 0.743), as summarized in Table 1. The distribution of sex is shown in Figure 1, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.357).

| Characteristics | Total amount | Age at diagnosis ≤ 17 yr | Age at diagnosis ≥ 18 yr | P value | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| 1.048 | (100) | 55 | (5.24) | 993 | (94.76) | ||

| Mean age at diagnosis (yr) | 39.2 | ± 16.1 | 12,2 | ± 4.2 | 40,7 | ± 15.1 | NA |

| Mean actual age (yr) | 42.0 | ± 16.1 | 15,3 | ± 4.6 | 43,5 | ± 15.0 | NA |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 433 | (41.3) | 25 | (44.6) | 408 | (41.1) | 0.522 |

| Female | 615 | (58.7) | 30 | (55.4) | 585 | (58.9) | |

| IBD | |||||||

| Crohn's disease | 357 | (34.1) | 30 | (54.5) | 327 | (32.9) | 0.004 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 669 | (63.2) | 24 | (43.7) | 645 | (65) | |

| Unclassified IBD | 22 | (2.1) | 1 | (1.8) | 21 | (2.1) | |

The distribution of UC and CD phenotypes was compared with that in the adult group, and we observed the highest frequency of pancolitis in UC and perianal disease in CD in the group ≤ 17 years, as shown in Table 2. Perianal disease is more associated with fistulizing disease in CD, as shown in Figure 2. The distribution of biologics used in this group was compared with that in the adult group, and no significant difference was observed, as shown in Table 3.

| Characteristics | Total amount | Age at diagnosis ≤ 17 yr old | Age at diagnosis ≥ 18 yr old | P value | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| 1.048 | (100) | 56 | (5.34) | 992 | (94.66) | ||

| Ulcerative Colitis | 669 | (63.2) | 24 | (42.9) | 645 | (65.0) | |

| Extension | |||||||

| E1 | 198 | (30.3) | 3 | (12.5) | 195 | (31.0) | 0.0371 |

| E2 | 247 | (37.9) | 6 | (25.0) | 241 | (38.4) | 0.183 |

| E3 | 209 | (32.0) | 15 | (62.5) | 194 | (30.8) | 0.001 |

| Crohn's disease | 352 | (34.1) | 30 | (55.4) | 322 | (32.9) | |

| Localization | |||||||

| L1 | 11 | (31.4) | 5 | (16.1) | 408 | (41.1) | 0.194 |

| L2 | 102 | (28.9) | 10 | (32.3) | 584 | (58.9) | 0.861 |

| L3 | 109 | (30.4) | 11 | (35.5) | 92 | (28.6) | 0.698 |

| L4 | 11 | (30.4) | 1 | (1.8) | 10 | (1) | |

| L1+L4 | 8 | (2.3) | 1 | (3.2) | 7 | (2.2) | |

| L3+L4 | 12 | (3.4) | 2 | (6.5) | 10 | (3.1) | |

| Behavior | |||||||

| B1 | 200 | (56.5) | 18 | (60.0) | 182 | (56.3) | 0.686 |

| B2 | 76 | (21.5) | 1 | (3.3) | 75 | (23.3) | 0.0051 |

| B3 | 75 | (21.2) | 11 | (36.7) | 64 | (19.5) | 0.030 |

| Perianal disease | 92 | (25.9) | 14 | (46.6) | 78 | (24.1) | 0.007 |

| Biological | Total amount | Age at diagnosis ≤ 17 yr old | Age at diagnosis > 18 yr old | P value | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| 1.048 | (100) | 55 | (5.24) | 993 | (94.76) | ||

| IBD | 187 | (17.8) | 19 | (34.5) | 168 | (16.9) | P = 0.001 |

| CD | 155 | (43.5) | 17 | (56.7) | 138 | (42.2) | P = 0.126 |

| UC | 30 | (4.5) | 2 | (8.3) | 28 | (4.3) | P = 0.353 |

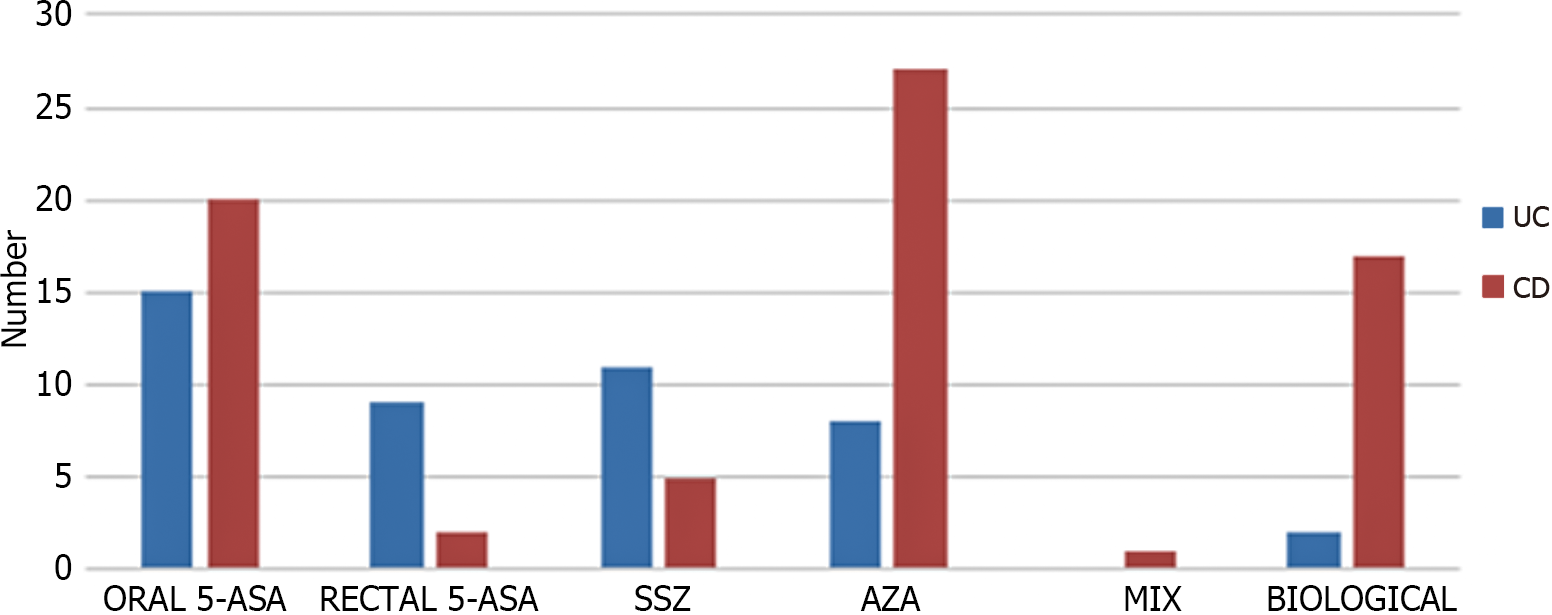

Oral aminosalicylates (mesalazine/sulfasalazine) were the drugs most used in UC, and in CD, we observed a greater use of the immunomodulators than aminosalicylates, as shown in Figure 3.

This is the first epidemiological study of the incidence and regional prevalence of IBD in a pediatric/adolescent population in a state of our country based on searches at the National Center in Biotechnology Information. There is a documented increase in the incidence and prevalence of pediatric IBD worldwide, and although this information is of great value for the planning of the health system, the few existing studies present different methodologies, which makes a more reliable analysis difficult[3,16-20].

In this study, we observed that the prevalence of IBD ≤ 17 years in the state of Espírito Santo, southeastern Brazil, in 2014 was 5.02 cases/100.000 inhabitants/year (CD: 2.73/100.000 and UC: 2.19/100.000), higher than the prevalence of IBD in Mexico[18] in Central America in patients < 18 years old, with 0.18 cases/100.000 inhabitants, but much lower than other regions, as in the 2017 study by Ludvigsson et al[3], in Sweden that analyzed data between 1993 to 2010 and reported 75 cases/100.000 inhabitants (CD 29/100.000 and UC: 25/100.000) and the 2019 study by Jones et al[21] in Scotland that analyzed data from 2009 to 2018 and found prevalence in children under 17 of 106 cases/100.000 inhabitants. Roberts et al[22], 2020, in a systematic review of pediatric IBD in Europe, found few prevalence studies using national and regional data. The highest prevalence rates of CD were approximately 60/100.000 in Hungary from 2011 to 2013. Regarding UC, the highest prevalence was approximately 30/100.000 in 3 regions: Hungary, Sweden and Denmark[22]. In North America, in Canada (Manitoba), 1978-2007 study showed an increase in prevalence from 3.1 to 18.9/100.000 in CD and UC from 0.7 to 12.7/100.000 inhabitants in UC[23].

The incidence of pediatric IBD in this study was 1.36 cases/100000 inhabitants/year, with equivalent CD and UC values of 0.63/100,000. Our incidence was higher than that observed in Argentina (0.4/100.000)[17] and Mexico (0.04/100.000)[18] but lower than that in other areas of the world, as noted in the 2018 systematic review of the incidence of IBD in children/adolescents from Sýkora et al[16], from 1985 to 2018, which found that the highest annual pediatric incidences of IBD were 23/100.000 person/years in Europe (Finland), 15.2/100.000 in North America (Canada) and 11.4/100.000 in Asia/Middle East and Oceania. However, the highest pediatric CD incidence was 13.9/100.000 in North America (Canada), followed by 12.3/100000 in Europe (France). Regarding UC, the highest annual incidence was 15.0/100.000 in Europe (Finland) and 10.6/100.000 in North America (Canada)[16]. In the analysis of incidence and prevalence, we can conclude that we still have low rates.

The frequency of IBD in the pediatric range in our region was 5.34%, below the global values (10% to 25%)[2,6]. Despite different methodologies, this study had a higher frequency than the West-Eastern European study in 2014 of children under 15 years of age, which presented a frequency of 3% (45/1560 patients)[19], and less than a study in Mexico in 2015, which showed that the frequency in pediatric patients under 18 years was 7.1% (32/479)[18].

In the distribution of IBDs, there was a slight predominance of CD (54.5%) compared to UC. Worldwide data are quite variable. A 2014 study by Burisch of West-Eastern Europe[19] found that Western Europe has an equivalent distribution between CD/UC, while Eastern Europe had a predominance of UC[19]. In Argentina[17], equivalence between CD and UC was observed. The study by Van Limbergem in the United Kingdom, 2008[6] observed a predominance of CD (66%) vs. UC (23.7%) in 416 pediatric patients < 17 years old. Buderus et al[20], 2015, found a predominance of CD (64%) in relation to UC (29%) in Germany, and Chaparro, 2018[24] also found a predominance of CD (61.5%) in Spain (2007-2017). In Mexico, the Yamamoto-Furusho study[18] observed a predominance of UC in 2015 (85%). We still have much diversity in the distribution of the disease.

In the study of the UC phenotype, pancolitis prevailed, similar to other pediatric studies worldwide[16-18,21,24]. In addition, our study showed a significant difference in relation to the adult group, with a higher frequency of extensive disease (pancolitis) in younger people.

In pediatric DC, the ileocolonic form predominated, as in other studies from Germany[20], Italy[25], Spain[24], Argentina[18] and Mexico[18]. Four patients had involvement of the upper intestinal tract (16%), similar to a study in Spain (15.4%)[24] but different from the results in Germany (53.6%)[20]. These differences may have occurred due to the limitations of the current study, as they were based on secondary data, and possibly, a smaller study of the upper gastrointestinal tract using imaging methods was performed.

Our study showed no significant difference in the location of CD in relation to adult patients.

We observed a high frequency of perianal disease ("p") with 46.6% of pediatric/adolescent CD, which demonstrates the most serious behavior in this age group. Our data were higher than those of a Germany study[20] with 11.5% perianal disease, of a Canadian study[26] with 16% perianal disease in 2019, and of a Spanish study[24] with 16.4% perianal disease in 2018. When compared to the adult group, we observed the highest frequency of fistulizing behavior (B3) and perianal disease (p) in the pediatric age group, that is, more severe behavior in the youngest.

In the treatment of UC, oral aminosalicylates (mesalazine/sulfasalazine) were the most commonly used drugs, compatible with current therapeutic recommendations[27]. The use of corticoids was not evaluated in this study, as they are not dispensed by this state health care sector, and at the time of this study, biologics were not approved in our country for pediatric patients[11].

On the other hand, in CD, we observed a greater use of the immunomodulators when compared to aminosalicylates, according to guidelines[28]. Biological therapy was used in 56.7% (17/30) of pediatric patients with CD, compared with 42.2% of adult patients, but no significant difference was found (P = 0.126). We observed a higher use of biologic therapy in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease when compared to the 15% of the Hungarian study (2011-2013)[29] and 7.7% in the study from Poland (2012-2014)[30] We were able to observe that the use of medication in our region is consistent with the data from the literature recommendations[27,28], but we can see that pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease used more frequent biologic therapy than those in another study.

In Brazil, where the incidence and prevalence of IBD are increasing in adults, it was observed that the prevalence and incidence in pediatric age are higher than those in other regions in Latin America, lower than those in Europe and North America, and in relation to the data worldwide, our pediatric IBD prevalence and incidence are still low. Children and adolescents with UC had a more extensive form (pancolitis) than adults, as in CD, and fistulizing forms (B3) and perianal diseases ("p") were more prevalent, which led to the high frequency of biological therapy in these patients with IBD before the age ≤ 17 years. These data, added to other epidemiological studies, demonstrate the severity of IBD in the pediatric age group, with the need for early diagnosis and early intervention and correct use of specific therapy, avoiding serious secondary damage during the disease´s evolution.

Although we recognize the limitations of this study, as not all patients included had a complete imaging study (magnetic resonance imaging, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy/biopsy) and secondary data based on documentation of the Public Health System was used, it is the first epidemiological pediatric IBD data published in the country. Although more studies are needed, this reports includes real-world data that can contribute to the planning of public health actions.

Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in a region of Brazil.

The pediatric inflammatory bowel disease data are practically unknown in Brazil and South America.

To determine the epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease and its characteristics in Brazil and South America.

The data were retrieved from the Public Medication-Dispensing System of the Department of Health in Espírito Santo state of Brazil.

The prevalence and incidence in pediatric ages are higher than those in other regions in Latin America. More severe disease was observed in the youngest patients. Pancolitis is more frequent in ulcerative colitis, and fistulizing and perianal disease are more frequent in Crohn's disease. Use of biological therapy was compared in the pediatric and adult groups.

We have little data on inflammatory bowel disease in Latin America. We need to better understand the epidemiology, phenotype and medication used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in each region.

Obtain better therapeutic approaches and contribute to the planning of public health actions.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Day AS, New Zealand; Wen XL, China; Xiao Y, China A-Editor: Elpek GO, Turkey S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, Kaplan GG. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46-54.e42; quiz e30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3789] [Cited by in RCA: 3524] [Article Influence: 271.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | Benchimol EI, Fortinsky KJ, Gozdyra P, Van den Heuvel M, Van Limbergen J, Griffiths AM. Epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of international trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:423-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 749] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ludvigsson JF, Büsch K, Olén O, Askling J, Smedby KE, Ekbom A, Lindberg E, Neovius M. Prevalence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Sweden: a nationwide population-based register study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ricciuto A, Fish JR, Tomalty DE, Carman N, Crowley E, Popalis C, Muise A, Walters TD, Griffiths AM, Church PC. Diagnostic delay in Canadian children with inflammatory bowel disease is more common in Crohn's disease and associated with decreased height. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:319-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fernandes A, Bacalhau S, Cabral J. [Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: is it still increasing? Acta Med Port. 2011;24 Suppl 2:333-338. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Drummond HE, Aldhous MC, Round NK, Nimmo ER, Smith L, Gillett PM, McGrogan P, Weaver LT, Bisset WM, Mahdi G, Arnott ID, Satsangi J, Wilson DC. Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1114-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 759] [Cited by in RCA: 701] [Article Influence: 41.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Victoria CR, Sassak LY, Nunes HR. Incidence and prevalence rates of inflammatory bowel diseases, in midwestern of São Paulo State, Brazil. Arq Gastroenterol. 2009;46:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Parente JM, Coy CS, Campelo V, Parente MP, Costa LA, da Silva RM, Stephan C, Zeitune JM. Inflammatory bowel disease in an underdeveloped region of Northeastern Brazil. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1197-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Lima Martins A, Volpato RA, Zago-Gomes MDP. The prevalence and phenotype in Brazilian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gasparini RG, Sassaki LY, Saad-Hossne R. Inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology in São Paulo State, Brazil. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:423-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde (Brasil). Portaria SAS/MS n 2.981, de 04 de novembro de 2002, Protocolo clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas da Retocolite Ulcerativa Idiopática. Brasilia. Acessed 15 november 2019. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/protocolo_clinico_diretrizes_terapeuticas_retocolite_ulcerativa.pdf. |

| 12. | Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde (Brasil). Portaria SAS/MS n 711, de 17 de dezembro de 2010. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas da Doença de Crohn. Brasilia. Acessed 15 november 2019. Available from: http://conitec.gov.br/images/Protocolos/Portaria_Conjunta_14_PCDT_Doenca_de_Crohn_28_11_2017.pdf. |

| 13. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K, Jewell DP, Karban A, Loftus EV Jr, Peña AS, Riddell RH, Sachar DB, Schreiber S, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Vermeire S, Warren BF. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2148] [Cited by in RCA: 2366] [Article Influence: 215.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Instituo Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Acessed 03 august 2015. Available from: ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2014/estimativas_2014_TCU.pdf. |

| 15. | Observatório da Criança e Adolescente. Accessed 3 March 2020. Available from: https://observatoriocrianca.org.br/cenarioinfancia/temas/populacao/1048-estratificacao-da-populacao-estimada-pelo-ibge-segundo-faixas-etarias?filters=1,1620. |

| 16. | Sýkora J, Pomahačová R, Kreslová M, Cvalínová D, Štych P, Schwarz J. Current global trends in the incidence of pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2741-2763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 17. | Vicentín R, Wagener M, Pais AB, Contreras M, Orsi M. One-year prospective registry of inflammatory bowel disease in the Argentine pediatric population. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115:533-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Sarmiento-Aguilar A, Toledo-Mauriño JJ, Bozada-Gutiérrez KE, Bosques-Padilla FJ, Martínez-Vázquez MA, Marroquín-Jiménez V, García-Figueroa R, Jaramillo-Buendía C, Miranda-Cordero RM, Valenzuela-Pérez JA, Cortes-Aguilar Y, Jacobo-Karam JS, Bermudez-Villegas EF; EPIMEX Study Group. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Mexico from a nationwide cohort study in a period of 15 years (2000-2017). Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Burisch J, Pedersen N, Čuković-Čavka S, Brinar M, Kaimakliotis I, Duricova D, Shonová O, Vind I, Avnstrøm S, Thorsgaard N, Andersen V, Krabbe S, Dahlerup JF, Salupere R, Nielsen KR, Olsen J, Manninen P, Collin P, Tsianos EV, Katsanos KH, Ladefoged K, Lakatos L, Björnsson E, Ragnarsson G, Bailey Y, Odes S, Schwartz D, Martinato M, Lupinacci G, Milla M, De Padova A, D'Incà R, Beltrami M, Kupcinskas L, Kiudelis G, Turcan S, Tighineanu O, Mihu I, Magro F, Barros LF, Goldis A, Lazar D, Belousova E, Nikulina I, Hernandez V, Martinez-Ares D, Almer S, Zhulina Y, Halfvarson J, Arebi N, Sebastian S, Lakatos PL, Langholz E, Munkholm P; EpiCom-group. East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63:588-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Buderus S, Scholz D, Behrens R, Classen M, De Laffolie J, Keller KM, Zimmer KP, Koletzko S; CEDATA-GPGE Study Group. Inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric patients: Characteristics of newly diagnosed patients from the CEDATA-GPGE Registry. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:121-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jones GR, Lyons M, Plevris N, Jenkinson PW, Bisset C, Burgess C, Din S, Fulforth J, Henderson P, Ho GT, Kirkwood K, Noble C, Shand AG, Wilson DC, Arnott ID, Lees CW. IBD prevalence in Lothian, Scotland, derived by capture-recapture methodology. Gut. 2019;68:1953-1960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Roberts SE, Thorne K, Thapar N, Broekaert I, Benninga MA, Dolinsek J, Mas E, Miele E, Orel R, Pienar C, Ribes-Koninckx C, Thomson M, Tzivinikos C, Morrison-Rees S, John A, Williams JG. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Incidence and Prevalence Across Europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1119-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | El-Matary W, Moroz SP, Bernstein CN. Inflammatory bowel disease in children of Manitoba: 30 years' experience of a tertiary center. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:763-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chaparro M, Garre A, Ricart E, Iglesias-Flores E, Taxonera C, Domènech E, Gisbert JP; ENEIDA study group. Differences between childhood- and adulthood-onset inflammatory bowel disease: the CAROUSEL study from GETECCU. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:419-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Castro M, Papadatou B, Baldassare M, Balli F, Barabino A, Barbera C, Barca S, Barera G, Bascietto F, Berni Canani R, Calacoci M, Campanozzi A, Castellucci G, Catassi C, Colombo M, Covoni MR, Cucchiara S, D'Altilia MR, De Angelis GL, De Virgilis S, Di Ciommo V, Fontana M, Guariso G, Knafelz D, Lambertini A, Licciardi S, Lionetti P, Liotta L, Lombardi G, Maestri L, Martelossi S, Mastella G, Oderda G, Perini R, Pesce F, Ravelli A, Roggero P, Romano C, Rotolo N, Rutigliano V, Scotta S, Sferlazzas C, Staiano A, Ventura A, Zaniboni MG. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents in Italy: data from the pediatric national IBD register (1996-2003). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1246-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dhaliwal J, Walters TD, Mack DR, Huynh HQ, Jacobson K, Otley AR, Debruyn J, El-Matary W, Deslandres C, Sherlock ME, Critch JN, Bax K, Seidman E, Jantchou P, Ricciuto A, Rashid M, Muise AM, Wine E, Carroll M, Lawrence S, Van Limbergen J, Benchimol EI, Church P, Griffiths AM. Phenotypic Variation in Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease by Age: A Multicentre Prospective Inception Cohort Study of the Canadian Children IBD Network. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:445-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Turner D, Ruemmele FM, Orlanski-Meyer E, Griffiths AM, de Carpi JM, Bronsky J, Veres G, Aloi M, Strisciuglio C, Braegger CP, Assa A, Romano C, Hussey S, Stanton M, Pakarinen M, de Ridder L, Katsanos K, Croft N, Navas-López V, Wilson DC, Lawrence S, Russell RK. Management of Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis, Part 1: Ambulatory Care-An Evidence-based Guideline From European Crohn's and Colitis Organization and European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67:257-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ruemmele FM, Veres G, Kolho KL, Griffiths A, Levine A, Escher JC, Amil Dias J, Barabino A, Braegger CP, Bronsky J, Buderus S, Martín-de-Carpi J, De Ridder L, Fagerberg UL, Hugot JP, Kierkus J, Kolacek S, Koletzko S, Lionetti P, Miele E, Navas López VM, Paerregaard A, Russell RK, Serban DE, Shaoul R, Van Rheenen P, Veereman G, Weiss B, Wilson D, Dignass A, Eliakim A, Winter H, Turner D; European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation; European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Consensus guidelines of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1179-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 851] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 76.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kurti Z, Vegh Z, Golovics PA, Fadgyas-Freyler P, Gecse KB, Gonczi L, Gimesi-Orszagh J, Lovasz BD, Lakatos PL. Nationwide prevalence and drug treatment practices of inflammatory bowel diseases in Hungary: A population-based study based on the National Health Insurance Fund database. Dig Liver Dis 2016; 48(11): 1302-1307 [PMID: 27481587 DOI: 10.1016/j.dld.2016.07. |

| 30. | Holko P, Kawalec P, Stawowczyk E. Prevalence and drug treatment practices of inflammatory bowel diseases in Poland in the years 2012-2014: an analysis of nationwide databases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:456-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |