Published online Mar 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i3.102274

Revised: January 6, 2025

Accepted: February 6, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2025

Processing time: 149 Days and 16.3 Hours

The gut microbiome comprises a vast community of microbes inhabiting the human alimentary canal, playing a crucial role in various physiological functions. These microbes generally live in harmony with the host; however, when dysbiosis occurs, it can contribute to the pathogenesis of diseases, including osteoporosis. Osteoporosis, a systemic skeletal disease characterized by reduced bone mass and increased fracture risk, has attracted significant research attention concerning the role of gut microbes in its development. Advances in molecular biology have highlighted the influence of gut microbiota on osteoporosis through mechanisms involving immunoregulation, modulation of the gut-brain axis, and regulation of the intestinal barrier and nutrient absorption. These microbes can enhance bone mass by inhibiting osteoclast differentiation, inducing apoptosis, reducing bone resorption, and promoting osteoblast proliferation and maturation. Despite these promising findings, the therapeutic effectiveness of targeting gut microbes in osteoporosis requires further investigation. Notably, gut microbiota has been increasingly studied for their potential in early diagnosis, intervention, and as an adjunct therapy for osteoporosis, suggesting a growing utility in improving bone health. Further research is essential to fully elucidate the therapeutic potential and clinical application of gut microbiome modulation in the management of osteoporosis.

Core Tip: Gut microbiota significantly influences bone health, with dysbiosis linked to osteoporosis. Emerging research highlights the potential of microbiota-targeted therapies, including probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation, for osteoporosis management. However, challenges like mechanistic understanding and translation to human applications persist. Future research should focus on personalized approaches and multi-omics integration to develop effective microbiome-based treatments for bone health.

- Citation: Jha SS, Jeyaraman N, Jeyaraman M, Ramasubramanian S, Muthu S, Santos GS, da Fonseca LF, Lana JF. Cross-talks between osteoporosis and gut microbiome. World J Orthop 2025; 16(3): 102274

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i3/102274.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i3.102274

Osteoporosis, as defined by the World Health Organization, is a multifactorial systemic skeletal disease characterized by decreased bone mass and deterioration of bone tissue, leading to increased bone fragility and susceptibility to fractures[1,2]. This complex condition is influenced by a myriad of factors, including genetic determinants, diet, micronutrient intake, and environmental influences[3-5]. These elements collectively play crucial roles in bone metabolism, highlighting the need for a comprehensive understanding of the diverse contributors to the pathogenesis of osteoporosis[2,6].

In recent years, the role of gut microbiota in human health has garnered significant attention, particularly concerning its influence on bone health. Early studies, such as Di Stefano et al[7], provided pioneering evidence of a connection between bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine and the development of osteoporosis. This observation laid the groundwork for subsequent research into the intricate relationship between gut microbiota and bone health. Over the past five years, the exploration of gut microbiota alterations and their implications for bone metabolism has gained considerable momentum, driven by advances in microbiome research and an increasing recognition of the gut-bone axis as a critical area of study in osteoporosis[8-12]. This review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the current understanding of the relationship between gut microbiota and osteoporosis. Specifically, it seeks to (1) To elucidate the mechanisms by which gut microbiota influence bone metabolism, including their roles in osteoclastogenesis and osteoblast activity; (2) To discuss the functional significance of taxonomic shifts in gut microbiota associated with osteoporosis; (3) To evaluate the potential of microbial interventions in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis; and (4) To identify the challenges and future prospects in translating microbiome research into clinical applications for bone health.

The human gut microbiota is a vast and diverse community of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, which inhabit the gastrointestinal tract. This complex ecosystem comprises more than 1000 microbial species, collectively housing over a trillion microbes, outnumbering the human genome by a factor of 100[13-15]. The composition and function of the gut microbiota are influenced by a multitude of factors, beginning with the method of birth—whether vaginal delivery or cesarean section—continuing with infant feeding practices, and further shaped by host factors such as age, gender, and genetics, as well as environmental influences including diet, lifestyle, medications, and exposure to antibiotics[16]. By the age of three, the gut microbiota typically stabilizes, establishing a relatively consistent microbial population that interacts with the host throughout life.

The gut microbiota plays a vital role in numerous physiological processes, influencing gut physiology and function, modulating the endocrine system, facilitating the production and absorption of essential nutrients[17-21], contributing to energy extraction, and providing protection against pathogenic organisms through its impact on immune function[22-24]. The gut microbiota's ability to maintain homeostasis is crucial for the host's overall health; however, alterations in this microbial population, known as dysbiosis, can lead to a loss of these protective functions. Recent research has increasingly focused on the link between dysbiosis and various diseases, revealing that disruptions in gut microbiota composition are associated with a wide range of metabolic, inflammatory[25], and degenerative conditions[26-30]. In particular, dysbiosis has been implicated in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome, including type 2 diabetes[31,32], obesity[27,33], and cardiovascular diseases[34,35], as well as inflammatory bowel diseases[36,37]. Importantly, there is growing evidence that dysbiosis may also contribute to the development and progression of osteoporosis.

This connection is of significant interest, as it suggests that interventions targeting the gut microbiota could potentially offer novel therapeutic strategies for osteoporosis management. Furthermore, the unusual associations between dysbiosis and neurological disorders such as Parkinson's disease[38-40], Alzheimer's disease[41-43], autism spectrum disorder[44-46], and various cancers[47-51] underscore the systemic impact of gut microbiota[52] on human health and highlight the need for further exploration of these relationships.

Despite the advances in understanding the role of gut microbiota in health and disease, several knowledge gaps remain in the context of osteoporosis. The precise mechanisms by which gut microbiota influence bone metabolism are not yet fully elucidated, and the specific microbial species or communities that contribute to bone health or disease are still being identified. Moreover, the interaction between gut microbiota and other known risk factors for osteoporosis, such as genetic predisposition and dietary intake, requires further investigation. The potential for gut microbiota modulation as a therapeutic intervention in osteoporosis is a promising area of research that warrants more comprehensive exploration. This review aims to discuss the relationship between gut microbiota and osteoporosis, focusing on the mechanisms by which dysbiosis may contribute to bone loss and fracture risk.

The intricate relationship between gut microbiota and bone metabolism has been an area of burgeoning research since the early 2000s. Following the initial observations by Di Stefano et al[7] in 2001, which suggested an association between small intestine bacterial overgrowth and osteoporosis, subsequent studies have provided more definitive evidence supporting the role of gut microbiota in regulating bone mass[7]. A seminal study by Sjögren et al[53] in 2012 provided the first experimental in vivo evidence in mice, demonstrating that gut microbiota significantly influence bone mass formation, thus cementing the link between gut microbiota and bone metabolism.

Specific bacterial genera have been identified to influence bone cell activities, particularly osteoclastogenesis (the formation of osteoclasts) and osteoblast activity (bone-forming cells)[8,54-56]. For instance, Lactobacillus strains have been shown to inhibit osteoclast differentiation by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1β, which are critical for osteoclast formation[57,58]. Additionally, Limosilactobacillus reuteri

While changes in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and other taxonomic shifts have been observed in osteoporotic versus healthy individuals, the functional significance of these shifts lies in their impact on metabolic and immune pathways that regulate bone health. A lower Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio has been associated with increased inflammation and reduced short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, both of which can lead to enhanced bone resorption[62-65]. Additionally, an increase in Proteobacteria has been linked to oxidative stress and inflammatory responses that negatively affect bone density[66,67].

Given the association of specific microbial taxa with bone health, microbial interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) hold potential for preventing or treating osteoporosis[68-71]. By restoring a healthy balance of gut microbiota, these interventions may enhance SCFA production, improve calcium and vitamin D absorption, and modulate the immune system to reduce bone resorption[64,66,72,73]. However, the efficacy of these interventions requires further investigation through well-designed clinical trials.

Research into the gut microbiota of osteoporotic versus healthy individuals has revealed significant taxonomic differences, particularly at the phylum level. The human gut microbiota predominantly consists of four principal phyla: (1) Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota); (2) Firmicutes (Bacillota); (3) Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota); and (4) Actinobacteria (Actinomycetota)[74-76]. Of these, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes comprise approximately 90% of the healthy gut microbiota. In osteoporotic patients, however, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is notably lower compared to healthy individuals, suggesting a dysbiotic state[77]. Moreover, Actinobacteria have been positively correlated with bone mineral density (BMD)[78,79], while Proteobacteria have been negatively correlated with bone mass[80]. These taxonomic differences extend to the family and genus levels as well. At the family level, changes in the Lachnospiraceae family, which includes the Clostridium cluster XIVa, have been observed. At the genus level, several genera have been implicated in osteoporosis risk, particularly in individuals with lower BMD and bone loss. Notably, the genera Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Eggerthella, Dialister, Rikenellaceae, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Citrobacter, Pseudomonas, Succinivibrio, Desulfovibrio, and Eisenbergiella have been found in higher abundance in osteoporotic patients[68,81-83]. Conversely, other microbiota genera, though present in lower numbers, have also been associated with osteoporosis.

The alterations in gut microbiota at these three taxonomic levels—phylum, family, and genus—are critical in understanding the role of gut microbiota in bone health. The phylum level changes primarily involve shifts in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, as well as the levels of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria. At the family level, the Lachnospiraceae family, particularly the Clostridium cluster XIVa, plays a significant role. At the genus level, alterations in the populations of Bacteroides, Dialister, Eggerthella, Bifidobacterium, Veillonella, and Escherichia/Shigella are noteworthy[84,85].

The regulation of bone metabolism by gut microbes in the host is facilitated through several key mechanisms, including interactions with host metabolism, gut function, the immune system, and the endocrine system[86,87]. The gut possesses a unique permeable barrier that plays a critical role in these processes. Modulation of this barrier can significantly influence post-metabolism activities, such as nutrient absorption and digestion. This barrier also serves as a defense against harmful bacteria and metabolites. The proper functioning of the gut epithelium is largely dependent on the microbiota within the gut. When dysbiosis occurs, it can lead to alterations in the gut barrier, subsequently triggering bone resorption.

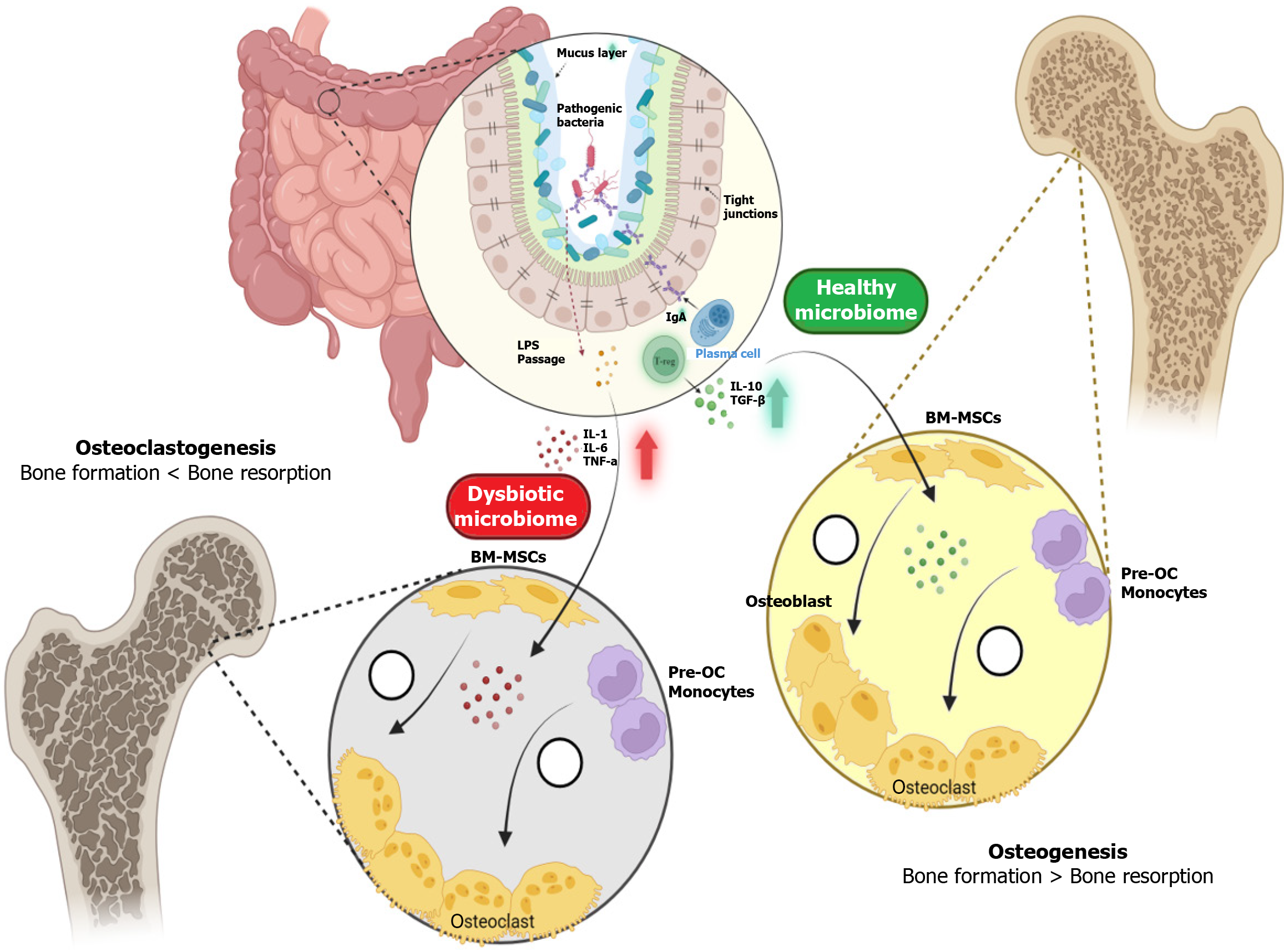

This complex sequence of events begins with the production of SCFAs by gut microbiota, which lowers the pH in the gut, thereby enhancing calcium absorption. SCFAs, including butyrate, propionate, and acetate, are metabolic byproducts of dietary fiber fermentation by symbiotic bacteria like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus[88-90]. These SCFAs not only play a pivotal role in enhancing calcium absorption but also support the integrity and function of the gut mucosal barrier. For instance, butyrate has anti-inflammatory properties and serves as a crucial energy source for colonocytes[91]. An increase in SCFA levels is directly linked to greater bone mass, as demonstrated in various in vivo studies that correlate higher SCFA levels with the prevention of bone loss. A healthy intestinal microbiome promotes bone formation by influencing the differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells toward the osteoblastic lineage, while simultaneously reducing osteoclast activity[8,92]. In contrast, a dysbiotic microbiome, characterized by an imbalance in microbial populations, leads to increased bone resorption and ultimately osteoporosis. This process is further illustrated in Figure 1.

SCFAs play a crucial role in maintaining an optimal environment for calcium absorption. The abundance of SCFAs in the gut lowers the pH of the intestinal lumen, which increases mineral solubility and inhibits the formation of calcium complexes like calcium phosphate[93]. This, in turn, enhances the bioavailability and absorption of calcium. Additionally, SCFAs promote paracellular calcium transport by influencing the intestinal epithelium, further contributing to bone mineralization and formation[94,95].

Vitamin D, in its active form (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D), is essential for calcium absorption in the gut, thereby playing a crucial role in maintaining calcium homeostasis[96]. Osteoblasts, the bone-forming cells, have vitamin D receptors (VDR) on their surfaces. When vitamin D binds to these receptors, it promotes bone formation. Conversely, a deficiency in vitamin D can lead to bone loss, increasing the risk of fractures. The regulation of vitamin D metabolism involves the fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), which is influenced by gut microbiota[97]. Inflammation in the colon, often associated with dysbiosis, has been shown to elevate FGF23 levels, subsequently reducing the availability of vitamin D[98]. Although the exact mechanisms underlying this process are not yet fully understood, the relationship between gut health and vitamin D metabolism is becoming increasingly evident.

In addition to vitamin D, vitamin K production is significantly influenced by gut microbiota, particularly by species such as Bacteroides. Up to 50% of vitamin K production is modulated by these microorganisms[99,100]. Vitamin K is crucial for bone health as it promotes osteoblast activity and inhibits the differentiation of osteoclasts, the cells responsible for bone resorption[101,102]. Moreover, vitamin K acts as a co-factor in the production of osteocalcin, a bone-specific protein essential for bone mineralization[103]. Dysbiosis, or the imbalance of gut microbiota, can impair vitamin K production, potentially disrupting bone homeostasis. While this hypothesis is promising, further research is needed to confirm the exact impact of dysbiosis on vitamin K production and bone health.

Another critical factor in bone metabolism is the interaction between vitamin D metabolism and bile acids. Primary bile acids are produced in the liver from cholesterol and are secreted into the small intestine to facilitate the absorption of dietary fats. Approximately 90% to 95% of these primary bile acids are reabsorbed in the intestine, while the remainder are transported to the colon, where they are converted into secondary bile acids by gut microbiota through a process known as deconjugation. Both primary and secondary bile acids can enter the systemic circulation and influence bone metabolism. Primary bile acids, through the activation of the farnesoid X receptor, promote bone formation and inhibit bone resorption[104,105]. However, secondary bile acids, particularly lithocholic acid (LCA), can have a detrimental effect on bone health. LCA binds to VDR, interfering with vitamin D metabolism and diminishing its beneficial effects on osteoblasts[106]. This interaction deprives the body of the full benefits of vitamin D, potentially leading to weakened bone formation and an increased risk of osteoporosis.

Dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in the gut microbiota composition, which can lead to altered metabolic and immune functions that negatively impact bone health. Specific microbial taxa and their metabolites play distinct roles in bone resorption and formation. For example, increased abundance of Proteobacteria and Desulfovibrio species is associated with heightened inflammatory responses and oxidative stress, promoting osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption[107]. Conversely, beneficial taxa such as Bifidobacterium and Clostridium cluster XIVa produce SCFAs that support osteoblast activity and inhibit osteoclast differentiation, thereby enhancing bone formation[82,93,108,109].

Bone homeostasis is intricately regulated by gut microbiota, primarily through the absorption of micronutrients and the production of essential vitamins. While calcium is a critical mineral for bone health, other minerals such as magnesium and phosphate also play vital roles.

Magnesium is essential for the structural development of bone and influences the activities of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Gut microbiota enhances magnesium absorption by producing SCFAs, which lower intestinal pH and increase the solubility of magnesium salts, thereby improving their bioavailability[110]. Similarly, phosphate absorption is facilitated by SCFAs, which enhance the expression of phosphate transporters in the intestinal epithelium[111]. Dysbiosis can impair the absorption of these minerals, leading to deficiencies that contribute to bone loss and increased fracture risk (Figure 2).

To counteract osteoporosis, the primary treatment options include antiresorptives and anabolics. Additional therapeutic measures, such as hormone replacement therapy and raloxifene, are also commonly used[112]. However, none of these treatments are foolproof in completely reversing bone loss. Despite the advances in pharmacological therapies, including the latest anabolic agent, romosozumab, which offers a dual mode of action for both prevention and treatment, significant limitations remain in fully restoring bone health.

With the growing understanding of the relationship between gut microbiota and bone metabolism, research has increasingly focused on the clinical application of microbial-related strategies for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Over the past decade, there has been a significant shift towards the development of new "functional foods" based on gut microbes, with emerging options that promote bone health. These include probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and fermented foods, all of which have shown promise in supporting bone health and potentially offering new avenues for osteoporosis management[113-116].

Probiotics, defined as "live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host", have gained attention for their potential role in bone health[117]. Among the probiotics, Lactobacillus strains have been particularly prominent in research, especially for their ability to modulate the immune system and prevent bone loss[118]. L. reuteri, known for its anti-inflammatory properties, has been shown to reduce intestinal inflammation and decrease the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, which is involved in bone resorption[119]. Additionally, L. reuteri helps maintain the Wnt signaling pathway, crucial for bone formation in vivo[60]. This strain has demonstrated the ability to prevent trabecular bone loss associated with conditions such as estrogen deficiency, type 1 diabetes, and glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis[120]. Human trials have further validated these findings, showing that daily oral administration of L. reuteri for 12 months prevented bone loss in osteoporotic women over the age of 75 years[121].

Other Lactobacillus strains have also shown promise in combating osteoporosis. For instance, Lacticaseibacillus paracasei has been found to inhibit osteoclastogenesis and prevent cortical bone loss in ovariectomized (OVX) mice, partly by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory markers TNF-α and IL-1β during a six-week regimen[122]. Similarly, Levilactobacillus brevis has demonstrated comparable effects[123]. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG has been noted for its ability to prevent the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in bone resorption and for promoting the expression of tight junction proteins, which enhance gut barrier function[121]. This strain also increases the production of SCFAs, thereby promoting bone formation and reducing inflammation in postmenopausal osteoporosis[121]. In addition to their effects on inflammation and bone resorption, these Lactobacillus strains also influence calcium and vitamin D metabolism. For example, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lacticaseibacillus casei, and Bifidobacterium species have been shown to significantly increase serum calcium levels[124]. L. casei and Bacillus coagulans are particularly effective in raising serum levels of 1,25-(OH)_2-vitamin D, while L. reuteri has been demonstrated to increase both serum 1,25-(OH)_2-vitamin D and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in humans[125].

Beyond Lactobacillus species, other probiotics such as Bifidobacterium longum (B. longum) have shown efficacy in preventing bone loss induced by estrogen deficiency in OVX rats, while also improving bone strength and BMD in vivo[126,127]. Similarly, Bifidobacterium lactis BL-99 has been effective in preventing colitis-induced osteoporosis in vivo[128]. The combination of Lactiplantibacillus plantarumas and B. longum has also been observed to enhance bone formation in OVX mice, improving levels of calcium, phosphorus, and osteocalcin while reducing TNF-α expression and downregulating microbial lipopolysaccharides[129]. The use of probiotics extends to other species as well. Phocaeicola vulgatus has been shown to mitigate dysbiosis in OVX mice, while Bacillus subtilis, over a 24-week regimen in postmenopausal women, has demonstrated the ability to increase BMD by inhibiting bone resorption[130]. This effect is achieved by decreasing the abundance of Fusobacterium and increasing the population of Bifidobacterium[131].

Prebiotics are defined as "non-digestible food ingredients that promote the growth and/or activity of specific bacteria, thereby benefiting the host's health"[132]. These complex carbohydrates, found naturally in plant-based foods or synthesized, are resistant to digestion in the stomach and small intestine. Instead, they are fermented by gut microbiota in the colon, particularly stimulating the proliferation of beneficial probiotic microorganisms such as Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus. This fermentation process leads to the production of SCFAs, enhances mineral bioavailability and absorption, and reduces inflammation, collectively contributing to improved bone health[133].

One example is galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), a prebiotic known for promoting the growth of Bifidobacteria, which in turn enhances calcium absorption and prevents bone loss, as observed in OVX rats[134]. Similar effects on calcium absorption and bone resorption inhibition have been noted in postmenopausal women[135]. Yacon flour, rich in fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), has been shown to improve bone strength in vivo, while dietary soluble corn fiber has demonstrated potential for increasing bone calcium absorption in postmenopausal women[136,137]. Nondigestible oligosaccharides found in tofu by-products, which include GOS, stachyose, and inulins, stimulate the growth of lactic acid bacteria in the gut. Inulin-type fructans, another prebiotic, have been shown to enhance mineral absorption and decrease markers of bone resorption in both animal models and postmenopausal women[138,139].

Synbiotics refer to the combined use of prebiotics and probiotics, which work together to enhance the proliferation of beneficial probiotics[140,141]. The dual application of GOS with B. longum and Bifidobacterium bifidum has been shown to significantly increase calcium absorption in vivo[142,143]. Similarly, combining FOS from yacon flour with B. longum positively impacts bone mineral content and bone strength, more effectively than prebiotics alone. In postmenopausal women, a regimen of fermented milk combined with inulin-type fructan prebiotics and additional calcium over two weeks has been found to reduce bone resorption while simultaneously increasing calcium absorption[143]. Overall, synbiotics have demonstrated greater efficacy in promoting bone health compared to the use of prebiotics or probiotics alone.

Fermented foods, which naturally contain probiotics and prebiotics, have also been explored for their bone health benefits. Fermented dairy products, such as yogurt and kefir, are rich in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains, which contribute to enhanced calcium and vitamin D absorption[144,145]. Additionally, fermented soy products like tempeh and miso contain isoflavones that, in combination with probiotics, may synergistically promote bone health by reducing inflammation and enhancing BMD[146,147].

While microbial-related therapeutics offer promising avenues for osteoporosis management, potential side effects must be considered. Probiotics are generally considered safe for most populations; however, in immunocompromised individuals, there is a risk of infections. Prebiotics can cause gastrointestinal discomfort, such as bloating and gas, particularly when consumed in large quantities. Synbiotics, which combine both probiotics and prebiotics, may exacerbate these side effects. Additionally, the long-term safety of FMT remains under investigation, with concerns about the transmission of pathogens and the stability of the transplanted microbiome[148-150]. Therefore, careful consideration and rigorous clinical testing are essential before widespread adoption of these therapies.

Several clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of microbial-related therapeutics in osteoporosis management. For instance, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that daily intake of L. reuteri significantly improved BMD in osteoporotic women over a 12-month period[121]. Another study involving postmenopausal women showed that supplementation with Bifidobacterium lactis BL-99 reduced bone resorption markers and improved BMD[128]. However, many studies are limited by small sample sizes, short durations, and lack of standardized protocols, highlighting the need for more robust clinical trials to establish the efficacy and safety of these interventions. Table 1 provides a summary of various microbial-related therapeutics, the specific microbial strains involved, their mechanisms of action, and the observed clinical outcomes related to bone health.

| Therapeutic type | Microbial strains | Mechanisms of action | Clinical outcomes |

| Probiotics | Lactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus paracasei, B. longum | Inhibit osteoclastogenesis, promote osteoblast activity, enhance calcium and vitamin D absorption | Increased BMD, reduced bone resorption, prevention of bone loss in clinical trials |

| Prebiotics | Galacto-oligosaccharides, fructo-oligosaccharides, Inulin-type fructans | Stimulate growth of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus, increase short-chain fatty acid production, enhance mineral absorption | Improved calcium absorption, increased bone strength, reduced markers of bone resorption |

| Synbiotics | Combination of prebiotics and B. longum, Bifidobacterium bifidum | Enhanced probiotic proliferation, increased calcium absorption, reduced inflammation | Greater improvement in bone mineral content and strength compared to prebiotics or probiotics alone |

| Fermented foods | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium strains in yogurt, kefir, tempeh | Natural source of probiotics and prebiotics, enhanced nutrient absorption | Improved calcium and vitamin D absorption, increased BMD in consumers |

Osteoporosis is influenced by a variety of factors, including genetic predisposition, lifestyle choices, and diet. Pharmacological interventions play a crucial role in improving bone health under both physiological and pathological conditions. However, recent research has increasingly focused on the role of gut microbiota in the development and management of osteoporosis. Gut microbes have been implicated in triggering inflammation in bone marrow and other tissues, either through direct modifications of the bacteria or via their metabolites. These microbes undergo complex processes to exert beneficial effects on bone health, and restoring and maintaining a balanced intestinal flora has been proposed as a therapeutic strategy for various conditions, including osteoporosis.

One approach to achieving this balance involves altering dietary habits and administering probiotics or their metabolites. This strategy helps restore the equilibrium of the intestinal flora. Key components in this process include dietary fibers, carbohydrates, SCFAs, and oligosaccharides, which collectively promote the growth of beneficial intestinal microbes and activate anti-inflammatory responses. As a result, calcium absorption from the intestine is enhanced, leading to an increase in BMD. Dairy products, which are rich in oligosaccharides, can also contribute to increased BMD. Specific strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium have been identified for their anti-inflammatory properties and their ability to enhance vitamin D absorption. These probiotics reduce osteoclast differentiation and have been shown to prevent bone loss in OVX mice.

A particularly innovative therapeutic approach that has gained attention is the technique of FMT. This involves the transplantation of gut microbiota to restore a healthy microbial balance, which has been shown to improve bone health and address various diseases in animal models. In humans, this technique has already been successfully employed in the management of drug-resistant bacterial colitis. However, further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms involved and to validate the therapeutic efficacy of this technique in the management of bone mineral diseases like osteoporosis. If proven effective, FMT could play a pivotal role in osteoporosis treatment.

An interesting development in osteoporosis research has been the analysis of gut microflora in the feces of female osteoporosis patients, which has shown a correlation with their estrogen levels. Changes in estrogen levels appear to be proportionate to changes in gut microbial species, leading to osteoporosis. This discovery has opened up new avenues for the prevention of osteoporosis. For example, oral administration of probiotics combined with red clover extract, which is enriched with isoflavone aglycone, has been shown to significantly reduce bone loss caused by estrogen deficiency. This combination not only improves osteoporosis but also stimulates the production of beneficial estrogen metabolites, contributing to increased estrogen levels.

Moreover, the use of probiotics combined with red clover extract, alongside magnesium, calcium, and calcitonin, has proven to be more effective than using the clover complex alone. This multifaceted approach enhances bone health by leveraging the synergistic effects of probiotics, nutritional supplements, and plant-based compounds. As research progresses, these strategies may offer new, more effective options for managing and preventing osteoporosis, highlighting the critical role of gut health in bone metabolism.

The relationship between gut microbiota and osteoporosis has garnered significant interest, yet several challenges impede a comprehensive understanding and application of this knowledge in clinical settings.

One of the primary challenges lies in the inherent heterogeneity of gut microbiota composition across individuals. This diversity, influenced by a multitude of factors such as diet, lifestyle, genetics, and environmental exposures, results in substantial variability in microbiota profiles among different populations. The variation complicates efforts to identify specific microbial signatures associated with bone health or disease, thus hindering the development of universal therapeutic strategies.

Another significant challenge is the mechanistic ambiguity surrounding the influence of gut microbiota on bone metabolism. Despite advances in microbiome research, the precise mechanisms through which gut microbiota impact bone health remain poorly understood. Proposed pathways include modulation of the immune system, production of SCFAs, and alteration of intestinal permeability. However, the relative contributions of these mechanisms in different contexts, such as age, sex, and comorbidities, are unclear. The time-dependent effects of gut microbiota on bone health, as observed in various studies, suggest a complex interplay of factors that has not been fully elucidated, making it challenging to predict outcomes of microbiota-targeted interventions.

Much of the current understanding of the gut microbiota-osteoporosis link is derived from animal studies, particularly in rodents. While these models provide valuable insights, they also have limitations due to physiological differences between animals and humans. The gut microbiota composition and its interactions with the host immune system and bone metabolism can differ significantly across species. This translational gap poses a challenge in extrapolating findings from animal models to human populations, potentially leading to overestimation or underestimation of the microbiota's role in osteoporosis.

Confounding factors further complicate research in this area. The gut microbiota is highly sensitive to external influences such as diet, medications (especially antibiotics), and lifestyle, all of which can confound study results. For instance, antibiotic use is known to cause significant alterations in gut microbiota, which can, in turn, affect bone health. Disentangling the direct effects of microbiota from those of these confounding variables remains a significant challenge in both observational and interventional studies.

The lack of longitudinal data presents a major obstacle in understanding the dynamics of gut microbiota over time and its long-term impact on bone health. Most studies investigating the gut microbiota's role in osteoporosis are cross-sectional, providing only a snapshot of microbiota composition at a single time point. Longitudinal studies, which are essential to track changes over time, are resource-intensive and logistically challenging, leading to a scarcity of data on how gut microbiota changes correlate with the progression of osteoporosis.

Therapeutic application of microbiota-based interventions is another area fraught with challenges. The potential of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics as therapeutic interventions is promising, yet their efficacy in osteoporosis remains inconclusive. Variability in individual responses to these interventions adds another layer of complexity. Furthermore, the optimal strains, doses, and duration of probiotic or prebiotic supplementation for bone health have not been clearly established, leading to inconsistent results across studies. Ethical and practical considerations in human studies, particularly those involving vulnerable populations like the elderly, pose additional challenges. Manipulating the gut microbiota through interventions such as FMT raises ethical concerns, and the long-term safety and potential side effects of such interventions are not yet fully understood. These concerns necessitate caution and further research before these approaches can be widely applied in clinical settings.

The exploration of the gut microbiota's role in osteoporosis is a rapidly evolving field with significant implications for future research and clinical applications. Several promising avenues of investigation are emerging, each with the potential to deepen our understanding of the gut-bone axis and improve therapeutic strategies for osteoporosis.

One major area of interest is the development of microbiome-targeted therapies. As the connection between gut microbiota and bone health becomes clearer, probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics are being explored for their potential to modulate the gut microbiota in ways that could prevent or treat osteoporosis. Future research will likely focus on identifying specific microbial strains that are most beneficial for bone health, as well as optimizing the delivery and dosage of these therapies to maximize their efficacy. Additionally, the use of FMT to restore a healthy gut microbiome in osteoporotic patients represents a novel therapeutic approach that warrants further investigation.

The integration of multi-omics data, including genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and microbiomics, will be crucial for advancing our understanding of the gut microbiota's role in osteoporosis. By combining these datasets, researchers can gain a more comprehensive view of the molecular mechanisms through which the gut microbiome influences bone metabolism. This holistic approach could lead to the identification of new biomarkers for early diagnosis and the development of more precise and personalized treatments.

Emerging research suggests that the gut microbiota may influence bone health not only through direct metabolic interactions but also via the gut-brain axis. This complex communication network between the gut, brain, and bone is thought to play a role in regulating bone density and overall skeletal health. Understanding how changes in the gut microbiome affect brain function and, in turn, influence bone metabolism could open up new therapeutic possibilities, particularly for conditions like postmenopausal osteoporosis, which are associated with hormonal changes and neurological factors.

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of microbial metabolites, such as SCFAs, bile acids, and indole propionic acid, in bone metabolism. These metabolites can modulate inflammation, enhance calcium absorption, and influence the differentiation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Future research will likely focus on characterizing these metabolites more precisely and understanding their mechanisms of action in the context of bone health. Such insights could lead to the development of new dietary supplements or pharmacological agents that target these pathways.

The variability in gut microbiota composition among individuals suggests that personalized medicine approaches could be highly effective in treating osteoporosis. By analyzing a patient’s microbiome profile, clinicians could tailor treatments to their specific microbial makeup, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of interventions. This approach could also help identify individuals who are at higher risk of developing osteoporosis due to dysbiosis, allowing for earlier and more targeted prevention strategies.

To fully understand the long-term effects of gut microbiota on bone health, longitudinal studies involving large and diverse populations are needed. These studies would track changes in the gut microbiome over time and correlate them with bone density, fracture risk, and other clinical outcomes. Such research could provide robust data on how gut microbiota interventions affect bone health across different stages of life and in various demographic groups. Additionally, dynamic changes of gut microbiota in osteoporosis, differentiating roles during early versus late disease stages, should be investigated to tailor interventions appropriately.

Practical challenges in optimizing the delivery and dosage of probiotics or prebiotics must be addressed. Factors such as microbial strain stability, survivability through the gastrointestinal tract, and patient adherence to supplementation regimens are critical for the success of microbiome-based therapies. Developing encapsulation technologies and controlled-release formulations could enhance the efficacy of these interventions.

As research progresses, ethical and regulatory considerations will become increasingly important, particularly with regard to interventions like FMT and the use of genetically modified probiotics. Ensuring the safety and efficacy of these treatments, as well as addressing issues related to consent and accessibility, will be critical for their successful im

| Research direction | Focus areas | Potential outcomes |

| Microbiome-targeted therapies | Identification of beneficial strains, optimal delivery methods | Effective prevention and treatment strategies |

| Multi-omics integration | Combining genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, microbiomics | Comprehensive understanding of gut-bone mechanisms |

| Gut-brain-bone axis | Interaction between gut microbiota, brain function, bone metabolism | Novel therapeutic targets and interventions |

| Characterization of metabolites | Detailed study of short-chain fatty acids, bile acids, indole propionic acid | Development of targeted supplements or drugs |

| Personalized medicine | Microbiome profiling for tailored treatments | Enhanced efficacy and personalized prevention |

| Longitudinal studies | Tracking microbiota and bone health over time | Robust data on causality and intervention effects |

| Optimization of therapies | Delivery mechanisms, dosage, adherence strategies | Improved therapeutic outcomes and patient compliance |

| Ethical and regulatory frameworks | Safety, consent, accessibility of microbiota-based therapies | Safe and regulated clinical applications |

The relationship between gut microbiota and bone health represents a rapidly advancing field, offering significant insights into the pathogenesis and potential treatment of osteoporosis. Emerging evidence underscores the critical role of gut microbiota in bone metabolism, influencing processes such as calcium and other mineral absorption, immune modulation, and vitamin synthesis. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in gut microbiota, has been increasingly linked to bone loss and the progression of osteoporosis, highlighting the gut-bone axis as a pivotal area of study.

While the therapeutic potential of microbiota-targeted interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics, and FMT is promising, several challenges remain, including the need for a deeper mechanistic understanding and the translation of findings from animal models to human populations. Future research focusing on personalized medicine approaches, multi-omics integration, and the long-term effects of microbiota on bone health will be crucial. Additionally, addressing practical challenges in therapy optimization and navigating ethical and regulatory landscapes will facilitate the successful implementation of microbiome-based therapies in clinical practice. As the field progresses, the development of precise, microbiome-based therapies holds the potential to revolutionize osteoporosis management, offering new strategies to enhance bone health and prevent fractures.

| 1. | Sözen T, Özışık L, Başaran NÇ. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017;4:46-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 681] [Cited by in RCA: 1307] [Article Influence: 145.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Smit AE, Meijer OC, Winter EM. The multi-faceted nature of age-associated osteoporosis. Bone Rep. 2024;20:101750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Formosa MM, Christou MA, Mäkitie O. Bone fragility and osteoporosis in children and young adults. J Endocrinol Invest. 2024;47:285-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Marcucci G, Brandi ML. Rare causes of osteoporosis. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2015;12:151-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mäkitie RE, Costantini A, Kämpe A, Alm JJ, Mäkitie O. New Insights Into Monogenic Causes of Osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van Oostwaard M. Osteoporosis and the Nature of Fragility Fracture: An Overview. 2018 Jun 16. In: Fragility Fracture Nursing: Holistic Care and Management of the Orthogeriatric Patient [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer; 2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Di Stefano M, Veneto G, Malservisi S, Corazza GR. Small intestine bacterial overgrowth and metabolic bone disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1077-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Han D, Wang W, Gong J, Ma Y, Li Y. Microbiota metabolites in bone: Shaping health and Confronting disease. Heliyon. 2024;10:e28435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen Y, Wang X, Zhang C, Liu Z, Li C, Ren Z. Gut Microbiota and Bone Diseases: A Growing Partnership. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:877776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li R, Boer CG, Oei L, Medina-Gomez C. The Gut Microbiome: a New Frontier in Musculoskeletal Research. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2021;19:347-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xiao H, Wang Y, Chen Y, Chen R, Yang C, Geng B, Xia Y. Gut-bone axis research: unveiling the impact of gut microbiota on postmenopausal osteoporosis and osteoclasts through Mendelian randomization. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1419566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bhardwaj A, Sapra L, Tiwari A, Mishra PK, Sharma S, Srivastava RK. "Osteomicrobiology": The Nexus Between Bone and Bugs. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:812466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shanahan F, Ghosh TS, O'Toole PW. The Healthy Microbiome-What Is the Definition of a Healthy Gut Microbiome? Gastroenterology. 2021;160:483-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 56.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Van Hul M, Cani PD, Petitfils C, De Vos WM, Tilg H, El-Omar EM. What defines a healthy gut microbiome? Gut. 2024;73:1893-1908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Afzaal M, Saeed F, Shah YA, Hussain M, Rabail R, Socol CT, Hassoun A, Pateiro M, Lorenzo JM, Rusu AV, Aadil RM. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:999001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9292] [Cited by in RCA: 8068] [Article Influence: 620.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Hou K, Wu ZX, Chen XY, Wang JQ, Zhang D, Xiao C, Zhu D, Koya JB, Wei L, Li J, Chen ZS. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 1357] [Article Influence: 452.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jolly RD, Thompson KG, Winchester BG. Bovine mannosidosis--a model lysosomal storage disease. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1975;11:273-278. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Zhao M, Chu J, Feng S, Guo C, Xue B, He K, Li L. Immunological mechanisms of inflammatory diseases caused by gut microbiota dysbiosis: A review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;164:114985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fujisaka S, Watanabe Y, Tobe K. The gut microbiome: a core regulator of metabolism. J Endocrinol. 2023;256:e220111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ayakdaş G, Ağagündüz D. Microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs) as novel gut microbiome modulators in noncommunicable diseases. Heliyon. 2023;9:e19888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Clarke G, Stilling RM, Kennedy PJ, Stanton C, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Minireview: Gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:1221-1238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 784] [Article Influence: 71.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Boulangé CL, Neves AL, Chilloux J, Nicholson JK, Dumas ME. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med. 2016;8:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 720] [Cited by in RCA: 968] [Article Influence: 107.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Clemente-Suárez VJ, Redondo-Flórez L, Rubio-Zarapuz A, Martín-Rodríguez A, Tornero-Aguilera JF. Microbiota Implications in Endocrine-Related Diseases: From Development to Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines. 2024;12:221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Singh R, Zogg H, Wei L, Bartlett A, Ghoshal UC, Rajender S, Ro S. Gut Microbial Dysbiosis in the Pathogenesis of Gastrointestinal Dysmotility and Metabolic Disorders. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27:19-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | DeGruttola AK, Low D, Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E. Current Understanding of Dysbiosis in Disease in Human and Animal Models. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1137-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 662] [Article Influence: 73.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Acevedo-Román A, Pagán-Zayas N, Velázquez-Rivera LI, Torres-Ventura AC, Godoy-Vitorino F. Insights into Gut Dysbiosis: Inflammatory Diseases, Obesity, and Restoration Approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:9715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Belizário JE, Faintuch J. Microbiome and Gut Dysbiosis. Exp Suppl. 2018;109:459-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bidell MR, Hobbs ALV, Lodise TP. Gut microbiome health and dysbiosis: A clinical primer. Pharmacotherapy. 2022;42:849-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jeyaraman M, Nallakumarasamy A, Jain VK. Gut Microbiome - Should we treat the gut and not the bones? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2023;39:102149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zhou Z, Sun B, Yu D, Zhu C. Gut Microbiota: An Important Player in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:834485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jeyaraman M, Mariappan T, Jeyaraman N, Muthu S, Ramasubramanian S, Santos GS, da Fonseca LF, Lana JF. Gut microbiome: A revolution in type II diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2024;15:1874-1888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Geng J, Ni Q, Sun W, Li L, Feng X. The links between gut microbiota and obesity and obesity related diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;147:112678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 57.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nesci A, Carnuccio C, Ruggieri V, D'Alessandro A, Di Giorgio A, Santoro L, Gasbarrini A, Santoliquido A, Ponziani FR. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence on the Metabolic and Inflammatory Background of a Complex Relationship. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:9087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Rahman MM, Islam F, -Or-Rashid MH, Mamun AA, Rahaman MS, Islam MM, Meem AFK, Sutradhar PR, Mitra S, Mimi AA, Emran TB, Fatimawali, Idroes R, Tallei TE, Ahmed M, Cavalu S. The Gut Microbiota (Microbiome) in Cardiovascular Disease and Its Therapeutic Regulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:903570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 44.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lopetuso LR, Petito V, Graziani C, Schiavoni E, Paroni Sterbini F, Poscia A, Gaetani E, Franceschi F, Cammarota G, Sanguinetti M, Masucci L, Scaldaferri F, Gasbarrini A. Gut Microbiota in Health, Diverticular Disease, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Time for Microbial Marker of Gastrointestinal Disorders. Dig Dis. 2018;36:56-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lippert K, Kedenko L, Antonielli L, Kedenko I, Gemeier C, Leitner M, Kautzky-Willer A, Paulweber B, Hackl E. Gut microbiota dysbiosis associated with glucose metabolism disorders and the metabolic syndrome in older adults. Benef Microbes. 2017;8:545-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Li Z, Liang H, Hu Y, Lu L, Zheng C, Fan Y, Wu B, Zou T, Luo X, Zhang X, Zeng Y, Liu Z, Zhou Z, Yue Z, Ren Y, Li Z, Su Q, Xu P. Gut bacterial profiles in Parkinson's disease: A systematic review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023;29:140-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Romano S, Savva GM, Bedarf JR, Charles IG, Hildebrand F, Narbad A. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson's disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 99.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chan DG, Ventura K, Villeneuve A, Du Bois P, Holahan MR. Exploring the Connection Between the Gut Microbiome and Parkinson's Disease Symptom Progression and Pathology: Implications for Supplementary Treatment Options. J Parkinsons Dis. 2022;12:2339-2352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Seo DO, Holtzman DM. Current understanding of the Alzheimer's disease-associated microbiome and therapeutic strategies. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56:86-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chandra S, Sisodia SS, Vassar RJ. The gut microbiome in Alzheimer's disease: what we know and what remains to be explored. Mol Neurodegener. 2023;18:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 71.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Peddinti V, Avaghade MM, Suthar SU, Rout B, Gomte SS, Agnihotri TG, Jain A. Gut instincts: Unveiling the connection between gut microbiota and Alzheimer's disease. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2024;60:266-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Taniya MA, Chung HJ, Al Mamun A, Alam S, Aziz MA, Emon NU, Islam MM, Hong SS, Podder BR, Ara Mimi A, Aktar Suchi S, Xiao J. Role of Gut Microbiome in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Its Therapeutic Regulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:915701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Mehra A, Arora G, Sahni G, Kaur M, Singh H, Singh B, Kaur S. Gut microbiota and Autism Spectrum Disorder: From pathogenesis to potential therapeutic perspectives. J Tradit Complement Med. 2023;13:135-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Su Q, Wong OWH, Lu W, Wan Y, Zhang L, Xu W, Li MKT, Liu C, Cheung CP, Ching JYL, Cheong PK, Leung TF, Chan S, Leung P, Chan FKL, Ng SC. Multikingdom and functional gut microbiota markers for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Microbiol. 2024;9:2344-2355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ağagündüz D, Cocozza E, Cemali Ö, Bayazıt AD, Nanì MF, Cerqua I, Morgillo F, Saygılı SK, Berni Canani R, Amero P, Capasso R. Understanding the role of the gut microbiome in gastrointestinal cancer: A review. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1130562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kandalai S, Li H, Zhang N, Peng H, Zheng Q. The human microbiome and cancer: a diagnostic and therapeutic perspective. Cancer Biol Ther. 2023;24:2240084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Cheng WY, Wu CY, Yu J. The role of gut microbiota in cancer treatment: friend or foe? Gut. 2020;69:1867-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Sun J, Chen F, Wu G. Potential effects of gut microbiota on host cancers: focus on immunity, DNA damage, cellular pathways, and anticancer therapy. ISME J. 2023;17:1535-1551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Akbar N, Khan NA, Muhammad JS, Siddiqui R. The role of gut microbiome in cancer genesis and cancer prevention. Health Sci Rev. 2022;2:100010. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 52. | Rebersek M. Gut microbiome and its role in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Sjögren K, Engdahl C, Henning P, Lerner UH, Tremaroli V, Lagerquist MK, Bäckhed F, Ohlsson C. The gut microbiota regulates bone mass in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1357-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kwon Y, Park C, Lee J, Park DH, Jeong S, Yun CH, Park OJ, Han SH. Regulation of Bone Cell Differentiation and Activation by Microbe-Associated Molecular Patterns. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Duffuler P, Bhullar KS, Wu J. Targeting gut microbiota in osteoporosis: impact of the microbial based functional food ingredients. Food Sci Hum Well. 2024;13:1-15. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 56. | Lyu Z, Hu Y, Guo Y, Liu D. Modulation of bone remodeling by the gut microbiota: a new therapy for osteoporosis. Bone Res. 2023;11:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Sapra L, Dar HY, Bhardwaj A, Pandey A, Kumari S, Azam Z, Upmanyu V, Anwar A, Shukla P, Mishra PK, Saini C, Verma B, Srivastava RK. Lactobacillus rhamnosus attenuates bone loss and maintains bone health by skewing Treg-Th17 cell balance in Ovx mice. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Chen Z, Shao J, Yang Y, Wang G, Xiong Z, Song X, Ai L, Xia Y, Zhu B. Evaluation of Functional Components of Lactobacillus plantarum AR495 on Ovariectomy-Induced Osteoporosis in Mice And RAW264.7 Cells. Foods. 2024;13:3115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Zhou K, Xie J, Su Y, Fang J. Lactobacillus reuteri for chronic periodontitis: focus on underlying mechanisms and future perspectives. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2024;40:381-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Zhang J, Motyl KJ, Irwin R, MacDougald OA, Britton RA, McCabe LR. Loss of Bone and Wnt10b Expression in Male Type 1 Diabetic Mice Is Blocked by the Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri. Endocrinology. 2015;156:3169-3182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Locantore P, Del Gatto V, Gelli S, Paragliola RM, Pontecorvi A. The Interplay between Immune System and Microbiota in Osteoporosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2020;2020:3686749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Kim CH. Complex regulatory effects of gut microbial short-chain fatty acids on immune tolerance and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023;20:341-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 71.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Stojanov S, Berlec A, Štrukelj B. The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 1070] [Article Influence: 214.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Feng B, Lu J, Han Y, Han Y, Qiu X, Zeng Z. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the regulation of osteoporosis: new perspectives from gut microbiota to bone health: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e39471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Wallimann A, Magrath W, Thompson K, Moriarty T, Richards RG, Akdis CA, O'Mahony L, Hernandez CJ. Gut microbial-derived short-chain fatty acids and bone: a potential role in fracture healing. Eur Cell Mater. 2021;41:454-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Wang Y, Li Y, Bo L, Zhou E, Chen Y, Naranmandakh S, Xie W, Ru Q, Chen L, Zhu Z, Ding C, Wu Y. Progress of linking gut microbiota and musculoskeletal health: casualty, mechanisms, and translational values. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2263207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Zhou RX, Zhang YW, Cao MM, Liu CH, Rui YF, Li YJ. Linking the relation between gut microbiota and glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2023;41:145-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Zhang YW, Cao MM, Li YJ, Zhang RL, Wu MT, Yu Q, Rui YF. Fecal microbiota transplantation as a promising treatment option for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2022;40:874-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zheng XQ, Wang DB, Jiang YR, Song CL. Gut microbiota and microbial metabolites for osteoporosis. Gut Microbes. 2025;17:2437247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Hao L, Yan Y, Huang G, Li H. From gut to bone: deciphering the impact of gut microbiota on osteoporosis pathogenesis and management. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1416739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Quaranta G, Guarnaccia A, Fancello G, Agrillo C, Iannarelli F, Sanguinetti M, Masucci L. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation and Other Gut Microbiota Manipulation Strategies. Microorganisms. 2022;10:2424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Hansdah K, Lui JC. Emerging Insights into the Endocrine Regulation of Bone Homeostasis by Gut Microbiome. J Endocr Soc. 2024;8:bvae117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Li Z, Wang Q, Huang X, Wu Y, Shan D. Microbiome's role in musculoskeletal health through the gut-bone axis insights. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2410478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Ramires LC, Santos GS, Ramires RP, da Fonseca LF, Jeyaraman M, Muthu S, Lana AV, Azzini G, Smith CS, Lana JF. The Association between Gut Microbiota and Osteoarthritis: Does the Disease Begin in the Gut? Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Jeyaraman N, Jeyaraman M, Dhanpal P, Ramasubramanian S, Ragavanandam L, Muthu S, Santos GS, da Fonseca LF, Lana JF. Gut microbiome and orthopaedic health: Bridging the divide between digestion and bone integrity. World J Orthop. 2024;15:1135-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 76. | Waldbaum JDH, Xhumari J, Akinsuyi OS, Arjmandi B, Anton S, Roesch LFW. Association between Dysbiosis in the Gut Microbiota of Primary Osteoporosis Patients and Bone Loss. Aging Dis. 2023;14:2081-2095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Li C, Huang Q, Yang R, Dai Y, Zeng Y, Tao L, Li X, Zeng J, Wang Q. Gut microbiota composition and bone mineral loss-epidemiologic evidence from individuals in Wuhan, China. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30:1003-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Wang Y, Zhang X, Tang G, Deng P, Qin Y, Han J, Wang S, Sun X, Li D, Chen Z. The causal relationship between gut microbiota and bone mineral density: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1268935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Guss JD, Horsfield MW, Fontenele FF, Sandoval TN, Luna M, Apoorva F, Lima SF, Bicalho RC, Singh A, Ley RE, van der Meulen MC, Goldring SR, Hernandez CJ. Alterations to the Gut Microbiome Impair Bone Strength and Tissue Material Properties. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32:1343-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Xu Z, Xie Z, Sun J, Huang S, Chen Y, Li C, Sun X, Xia B, Tian L, Guo C, Li F, Pi G. Gut Microbiome Reveals Specific Dysbiosis in Primary Osteoporosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Ozaki D, Kubota R, Maeno T, Abdelhakim M, Hitosugi N. Association between gut microbiota, bone metabolism, and fracture risk in postmenopausal Japanese women. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32:145-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Yan L, Wang X, Yu T, Qi Z, Li H, Nan H, Wang K, Luo D, Hua F, Wang W. Characteristics of the gut microbiota and serum metabolites in postmenopausal women with reduced bone mineral density. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1367325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Das M, Cronin O, Keohane DM, Cormac EM, Nugent H, Nugent M, Molloy C, O'Toole PW, Shanahan F, Molloy MG, Jeffery IB. Gut microbiota alterations associated with reduced bone mineral density in older adults. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:2295-2304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Lai J, Gong L, Liu Y, Zhang X, Liu W, Han M, Zhou D, Shi S. Associations between gut microbiota and osteoporosis or osteopenia in a cohort of Chinese Han youth. Sci Rep. 2024;14:20948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Srivastava RK, Duggal NA, Parameswaran N. Editorial: Gut microbiota and gut-associated metabolites in bone health. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1232050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Tu Y, Kuang X, Zhang L, Xu X. The associations of gut microbiota, endocrine system and bone metabolism. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1124945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Portincasa P, Bonfrate L, Vacca M, De Angelis M, Farella I, Lanza E, Khalil M, Wang DQ, Sperandio M, Di Ciaula A. Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids: Implications in Glucose Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 157.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | O'Riordan KJ, Collins MK, Moloney GM, Knox EG, Aburto MR, Fülling C, Morley SJ, Clarke G, Schellekens H, Cryan JF. Short chain fatty acids: Microbial metabolites for gut-brain axis signalling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2022;546:111572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 86.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Mirzaei R, Dehkhodaie E, Bouzari B, Rahimi M, Gholestani A, Hosseini-Fard SR, Keyvani H, Teimoori A, Karampoor S. Dual role of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids on host and pathogen. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;145:112352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Liu H, Wang J, He T, Becker S, Zhang G, Li D, Ma X. Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health? Adv Nutr. 2018;9:21-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 455] [Cited by in RCA: 718] [Article Influence: 102.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Cooney OD, Nagareddy PR, Murphy AJ, Lee MKS. Healthy Gut, Healthy Bones: Targeting the Gut Microbiome to Promote Bone Health. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:620466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Wallace TC, Marzorati M, Spence L, Weaver CM, Williamson PS. New Frontiers in Fibers: Innovative and Emerging Research on the Gut Microbiome and Bone Health. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36:218-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Mineo H, Hara H, Tomita F. Short-chain fatty acids enhance diffusional ca transport in the epithelium of the rat cecum and colon. Life Sci. 2001;69:517-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 94. | Thammayon N, Wongdee K, Teerapornpuntakit J, Panmanee J, Chanpaisaeng K, Charoensetakul N, Srimongkolpithak N, Suntornsaratoon P, Charoenphandhu N. Enhancement of intestinal calcium transport by short-chain fatty acids: roles of Na(+)/H(+) exchanger 3 and transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 6. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024;326:C317-C330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Palacios C. The role of nutrients in bone health, from A to Z. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2006;46:621-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Bora SA, Kennett MJ, Smith PB, Patterson AD, Cantorna MT. The Gut Microbiota Regulates Endocrine Vitamin D Metabolism through Fibroblast Growth Factor 23. Front Immunol. 2018;9:408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Razzaque MS. Interactions between FGF23 and vitamin D. Endocr Connect. 2022;11:e220239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Pham VT, Dold S, Rehman A, Bird JK, Steinert RE. Vitamins, the gut microbiome and gastrointestinal health in humans. Nutr Res. 2021;95:35-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Tarracchini C, Lugli GA, Mancabelli L, van Sinderen D, Turroni F, Ventura M, Milani C. Exploring the vitamin biosynthesis landscape of the human gut microbiota. mSystems. 2024;9:e0092924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Akbari S, Rasouli-Ghahroudi AA. Vitamin K and Bone Metabolism: A Review of the Latest Evidence in Preclinical Studies. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:4629383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Su Y, Cappock M, Dobres S, Kucine AJ, Waltzer WC, Zhu D. Supplemental mineral ions for bone regeneration and osteoporosis treatment. ER. 2023;4:170-182. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Stock M, Schett G. Vitamin K-Dependent Proteins in Skeletal Development and Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Zheng T, Kang JH, Sim JS, Kim JW, Koh JT, Shin CS, Lim H, Yim M. The farnesoid X receptor negatively regulates osteoclastogenesis in bone remodeling and pathological bone loss. Oncotarget. 2017;8:76558-76573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Cho SW, An JH, Park H, Yang JY, Choi HJ, Kim SW, Park YJ, Kim SY, Yim M, Baek WY, Kim JE, Shin CS. Positive regulation of osteogenesis by bile acid through FXR. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:2109-2121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Ruiz-Gaspà S, Guañabens N, Enjuanes A, Peris P, Martinez-Ferrer A, de Osaba MJ, Gonzalez B, Alvarez L, Monegal A, Combalia A, Parés A. Lithocholic acid downregulates vitamin D effects in human osteoblasts. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Mostafavi Abdolmaleky H, Zhou JR. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Epigenetic Alterations in Metabolic Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024;13:985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |